Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.49 n.1 Pretoria Apr. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vol49n1a4

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Applying the occupational justice framework in disability policy analysis in Namibia

Tongai F ChichayaI; Robin JoubertII; Mary Ann McCollIII

IBSc OT (University of Zimbabwe), M Public Health, (University of Namibia) PhD (UKZN) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7860-4993

IINat Dip OT (Pret), BA (UNISA), MOT (UDW), DEd (UKZN) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7328-1590. Hon. Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy Discipline, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal

IIIBSc OT (Queens University), MHSc Com Health (Queens University), MTS Theological Studies (Queens Theological College), PhD (University of Toronto) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9408-4642 .Academic Lead, Canadian Disability Policy Alliance; Assistant Director, Centre for Health Services and Policy Research; Professor, Rehabilitation Therapy, Public Health Sciences, Queens University

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The purpose of the study was to compare the existing disability policy in Namibia with those of other southern African countries to determine whether the former would require revisions. There were two objectives: to apply the occupational justice framework to analyse the National Policy on Disability of Namibia, to conduct an comparative analysis of the National Policy on Disability of Namibia and selected disability policies and policy environments in Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe taking into consideration the United Nations' Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD)

METHODS: A qualitative analytical approach was used to conduct a document review of the Namibia disability policy and to provide a comparative analysis of the Namibia disability policy with those of selected southern African countries using the disability policy analysis lens. Critical disability theory provided the overarching theoretical framework. Discourse analysis was applied to identify themes.

FINDINGS: Embedded occupational marginalisation and deprivation were evident in the Namibian disability policy. A new type of occupational injustice emerged that can best be described as Occupational inconsideration among disability policy makers, whereby occupational rights for persons with disabilities are of secondary focus when disability policies are formulated.

CONCLUSION: Namibia's disability policy was considered inadequate in terms of addressing occupational rights according to the occupational justice framework. Similarly, Namibia and other southern African countries have not significantly progressed with domesticating the UNCRPD. The findings have implications for disability policy formulation and occupational justice practice in Namibia in particular and in southern Africa in general.

Key words: Occupational justice; disability policy; policy analysis; occupational participation; African countries.

INTRODUCTION

Background

This paper is underpinned by the occupational therapy premise that human beings are occupational beings1 and that participation in occupations is essential for human existence and well-being. Every individual therefore has occupational rights i.e. the right to participate in occupations that are meaningful to them and to bring well-being to individuals and communities2,3. Occupation in this context refers to everything people do, including self-care, making socio-economic contributions to their own communities, enjoying life, learning and finding meaning in life4. Persons with disabilities in Namibia face many physical and situational challenges as they try to negotiate the intricate maze of barriers to occupational participation5.

Occupational rights in the literature include rights to make decisions about daily life; to find meaning; to participate in occupations of choice; to be supported in occupational participation; and to obtain the adequate rewards for participation2,3. Any human-made barriers to occupational participation experienced by persons with disabilities are a violation of their occupational rights and can best be described as occupational injustice6. Occupational injustice exists when individuals are powerless to make decisions about their own life choices; they are thus restricted from participating in meaningful daily occupations that bring them fulfilment and satisfaction7,8. An occupationally-just environment is one in which individuals are empowered and enabled to participate in occupations that they choose and which are meaningful to them in their own context8.

For some years there has been an outcry among persons with disabilities in Namibia for being restricted, segregated and sometimes overtly or covertly barred from participating in the education system, socio-economic activities, health services, and a lack of equality with other citizens9, 10. To a large extent, occupational performance among persons with disabilities is hindered by external or environmental factors, which can be physical, socio-cultural, institutional and socio-political: poor policies and legislation, for example, rather than only by their impairment or health condition1,11. In this study, disability is defined according to the UNCRPD, which states: Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others12. The disability policy in Namibia uses the definition provided by Disabled People's International which defines disability as "the loss or limitation of opportunities to take part in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others due to physical or social barriers"131.

Over the years many disability models have been used; these include the medical model, the charity model, the economic model, the social model, the bio-psychosocial model, and more recently the human rights model14,15,16. The medical model views disability as a physical, mental or psychological condition that limits a person's activities and thus directs intervention towards medical rehabilitation and impairment correction15. The charity model views persons with disabilities as dependent and in need of charity; the economic model views persons with disabilities as members of the society in need of economic support from the governments in the form of social security and disability grants; the social model of disability conceptualises disability as arising from a negative interaction of a person's health condition or impairment with the environment. The environment could be physical infrastructure, cultural practices or policies guiding access to goods and services14. If the environment is designed for the full range of human functioning, and incorporates appropriate accommodations and supports, then people with functional limitations would not be viewed as 'disabled' in the sense that they would be able to fully participate in society11. The bio-psychosocial model incorporates the useful aspects of both the medical and social models17. The bio-psychosocial model integrates diagnostic medical information with psychosocial aspects of life, such as personality traits, coping abilities, stress, social support and environment18. The human rights model is gaining popularity worldwide and is currently emerging in Africa. This model can be considered as an improvement on the social model. The latter clearly articulates discrimination of persons with disabilities within society, but does not provide moral principles and values as a base for a disability policy19. The social model considers disability to be a human rights issue, based on the notion that all human beings are equal and have rights that have to be respected. People with disabilities are citizens and as such have the same rights as those without impairments, therefore all actions to support persons with disabilities should be rights-based.

This paper adopted the perspective of the human rights model of disability, as it is based on the same principles of occupational justice and the ethos of this study. A human rights-based approach to disability is about levelling the playing field for persons with disabilities to access livelihood, education, health and other services. It is also about removing physical and social barriers, and bringing about attitude adjustment among policy-makers, service providers and family members. Its aim is to have a society in which all persons with disabilities have the freedom to participate in the occupations of their need and choice.

The occupational justice framework and disability policy

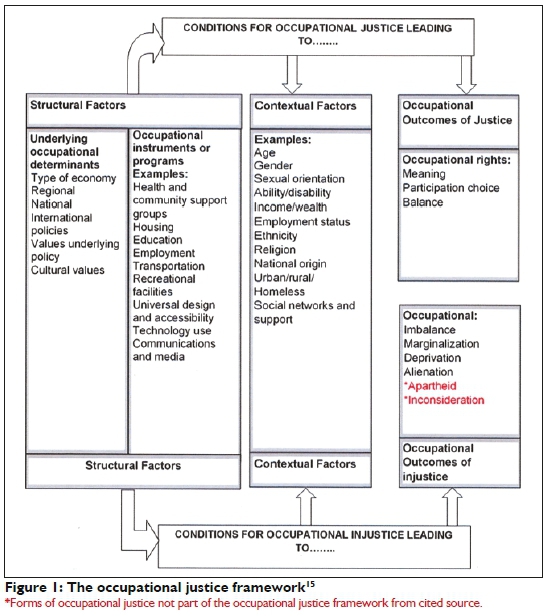

The occupational justice framework analyses and describes occupational injustice in order to generate knowledge that can be used to create an environment that is occupationally just for persons with disabilities. Occupational justice, as a conceptual framework, provides a population based approach to occupational therapy that promotes the rights for every individual to participate in meaningful occupations in order to reach their potential and flourish3,7. The occupational justice framework is an evolving concept that offers a critical occupational viewpoint of justice complementary to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD)12. It describes how structural and contextual factors interrelate to determine occupational justice outcomes20. Figure 1 on page 20 shows that policies are the underlying occupational determinants because occupation is contextual; policies form part of the structural factors that shape the context.

Different forms of occupational injustice have been described in the literature6. Sub-types of documented occupational injustice include: occupational alienation (a sense of isolation, loss of control, emptiness and meaningless life resulting from lack of resources and opportunities to participate in occupations that are meaningful); occupational deprivation (a state of prolonged denial of opportunity to engage in occupations of necessity due to factors outside the control of an individual); occupationalmarginalisation (whereby there are silent or hidden inequalities resulting in an individual not being entitled to occupational opportunities and resources that others are getting e.g. through restrictive policies or laws that limit people's choices or through not creating an accessible environment for persons with disabilities); occupational imbalance (configuration of a person's activities that results in compromised health and quality of life because of being over occupied or under-occupied); and occupational apartheid (deliberate exclusion or segregation of some populations from some occupational opportunities and resources)6,21.

Disability policy lens

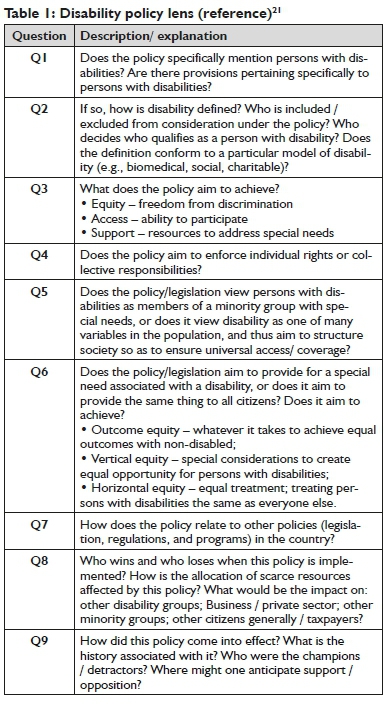

The disability policy lens was used to conduct a comparative analysis of the disability policies and legislation from other southern African countries with that of Namibia. By using the disability policy lens, key implications on policy decisions for persons with disabilities can be easily assessed using a set of nine questions22,23. Furthermore, it allows for a comparative analysis of different disability policies because each policy is subjected to the same set of questions. Table 1 on the right presents a list of the disability policy lens questions.

Research problems

The influence of policies on occupational performance is relatively under-researched by occupational scientists and occupational therapists24. Namibia's national policy on disability has not been reviewed since its inception in 199725. However, there has been a significant shift in the way disability is construed since then, not only in Africa, but globally. It is therefore timeous to provide evidence that could contribute to a more responsive disability policy formulation which promotes occupational justice.

Aim of the study

This study applied the occupational justice framework in an analysis of the national policy on disability in Namibia in order to conduct a comparative analysis of the respective disability policies of Botswana, Malawi, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, by taking into consideration the UNCRPD.

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research design, focusing on a document based disability policy analysis approach, was utilised in the study. The disability policy lens22,23 was used to extract key aspects from the disability policies in Namibia's neighbouring countries for the purpose of a comparative analysis. Critical disability theory was selected as the overarching theoretical framework and is a philosophical framework that seeks to liberate persons with disabilities from situations that subjugate them26. Critical disability theory describes persons with disabilities as 'oppressed' because society treats them in ways that diminish their social, personal, physical, and financial well-being, and they are viewed as members of a socially disadvantaged minority group27. It further focuses on a wider reality of a current situation: how things have come to be, the way they are, and what they might be in future28. Therefore, things or situations cannot be dogmatically accepted as they appear to be from a superficial perspective, since appearances have deeper hidden meanings which critical theory seeks to uncover. Written disability policies also have hidden meanings in their discourse29, which can promote or hinder occupational justice for persons with disabilities. The primary goal of the critical disability theory is to remove all barriers that hinder persons with disabilities from societal participation, and to let them be viewed as equals with those without disabilities30,31. Critical theory holds the view that solutions to human problems are always situated, and dependent, not only on being technically correct, but on what can be valued as desirable in terms of justice, fairness, happiness, and freedom: a perspective congruent with the occupational justice framework which focuses on structural and contextual factors that can create conditions for either occupational justice or occupational injustice.

Purposive sampling was used to select disability policy documents of southern African countries to undertake a comparative analysis with that of the disability policy of Namibia. This required that southern African countries had to be selected to obtain their respective policies.

Process of selecting southern African countries for inclusion in the study

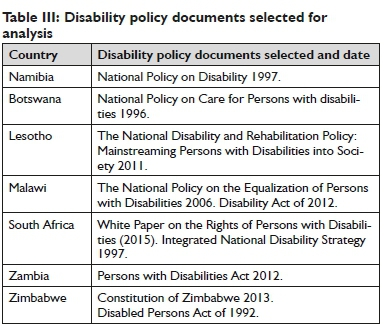

Southern Africa generally includes: Angola, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. A scooping scan of these countries was conducted whereby criteria that influence disability policy were applied. The criteria included: income status; population size; and inequality levels; domestication of the UNCRPD; political independence; existence of disability policy or legislation; and availability of adequate information to frame disability policy environment on government departments and organisations for people with disabilities websites for each country. Boolean search strategies were used to search for relevant disability policy documents from the following search engines: Google; Yahoo; Excite; and Bing. Countries with limited available information on the above criteria were eliminated from the study, and those that met the selection criteria are shown in Table II above.

Process for selecting documents for review in this study

Following the shortlisting of the southern African countries, the next step was to identify disability policies and or legislation to be selected for the document review. Selection of the documents for review (see Table II) were based on whether the policy, act, white paper, or constitution had been approved by the respective government cabinet of the respective countries. The most recent versions of policies or acts were purposively selected. Reports and other documents about disability policy were sought in a literature review to provide a contextual perspective. This was deemed necessary to analyse the discourse in the policies. Table III below shows the disability policy and legislation documents that were selected.

Data analysis

An occupational justice framework was applied to identify and to describe occupational injustice embedded in disability policy narratives and which were unearthed by discourse analysis. The discourse analysis of the Namibian disability policy in this study was guided by steps including: establishing the context; exploring the discourse production process; examining the structure of the text; examining discursive statements; identifying cultural references and rhetorical mechanisms32.

Ethical standards

Ethics clearance to conduct the study was obtained from the Humanities and Social Science Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and the Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS) in Namibia.

Disability context in Namibia

The disability policy in Namibia was adopted by parliament in 1997 following a national survey conducted by an expatriate consultant25. The policy adopted a social model perspective. According to the Namibia national housing and population census in 2011, there were 98 413 persons with disabilities across the 14 administrative regions of the country, accounting for approximately 5% of the total population33. These statistics are however questionable because the census questionnaire was impairment-based. Many disabilities such as those linked to developmental and mental conditions remain unnoticed or unreported, and coupled with a high prevalence of HIV, it is likely that the percentages are higher.

Several positive initiatives have been undertaken by the government with the intention of addressing the needs of persons with disabilities in Namibia. These include setting up a disability unit in the office of the prime minister in 2001; enacting of the National Disability Council Act 26 of 2004; signing the UNCRPD and its optional protocol in 2007; and more recently the appointment of a deputy minister for disability affairs in the office of the vice-president who does have disabilities.

The Namibia Federation of People with Disabilities (NFPDN) was established in 2001. It is the umbrella body for organisations for people with disabilities. However, due to mismanagement, operations stopped for many years, but the NFPDN is being revived despite financial challenges34. Similarly, the National Disability Council has had leadership challenges and has not acted on its mandate to initiate a review of the policy since inception despite a general consensus among stakeholders that the policy is outdated. The custodianship for disability issues was moved from the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation to the Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS), and more recently to the office of the vice-president34,35.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The findings are presented in terms of the two objectives of the study. Firstly, findings from the analysis of the National Policy on Disability of Namibia are presented and secondly, the findings from the comparative analysis of National Policy on Disability of Namibia and the selected disability policies and policy environments in Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe are discussed taking in consideration the UNCRPD.

Findings on analysis of the national policy on disability of Namibia

The occupational justice framework outlines structural factors and contextual factors that, when subjected to certain conditions, will lead to occupational justice or injustice. The structural factors comprise underlying occupational determinants and occupational instruments or programmes. Examples of occupational determinants include: type of economy, policies, values underlying the policies, and cultural values. Examples of occupational instruments or programmes include: housing, education, employment, and transportation. Contextual factors include: age, gender, employment status, income; dwelling, religion and disability.

Passive voices calling for action: a discourse of disempowerment

The policy predominately speaks in the passive voice. When passive voice is used there is no identification of who should take the responsibility to act. In contrast when an active voice is used the person taking the action is the subject of the sentence. The theme of passive voices calling for action is made up of two categories i.e. things that need to be done 'for' persons with disabilities and ambiguous directives. While the policy lists the occupational instruments identified in the occupational justice framework, the discourse does not empower persons with disabilities. Instead the discourse situates persons with disabilities as recipients of assistance. The use of the word 'shall' is common in the disability policy. However, this can be ambiguous as it can also mean 'may', 'will' or 'must'36. Recommendations are that where there are mandatory requirements 'must' has to be used; 'must not' for prohibition; 'may' for a discretionary action; and 'should' for a recommenda-tion37. The word 'shall' appears 75 times in the National Policy on Disability of Namibia; the word 'must' appears only twice. The frequent use of the ambiguous 'shall' in the disability policy makes it appear to be more rhetoric; this implicitly propagates a background for occupational injustice faced by persons with disabilities in Namibia.

All about them without them: occupational marginalisation

There is no evidence of active involvement of persons with disabilities in formulating the disability policy in Namibia. Analysis of the discourse in the policy revealed two main categories. Firstly, the striking absence of the voice and responsibilities of persons with disabilities in the policy.

Secondly, limited attention given to the disability movement. For example, section 3.2.20 talks about organisations of and for persons with disabilities. However, there are only two sentences on the last page of the policy that state that the government "recognises" the rights and roles of organisations for persons with disabilities and "...shall endeavour to encourage and support the formation and strengthening of such organizations..." 258. The use of the words "shall endeavour" takes away the responsibility of providing the rights of persons with disabilities as a "must"; to endeavour means to try or attempt and has a tacit apathy revealed in its intention.

When the decision-making process on issues affecting persons with disabilities excludes persons with disabilities, conditions for occupational marginalisation are created, and their choices for occupational participation are restricted6,29. This is in conflict with the motto 'Nothing about us without us' for persons with disabilities. When the two mentioned categories were further analysed the resulting theme is a situation that can best be described as 'All about them without them' because policy decision-makers without disabilities determine what needs to be done for persons with disabilities without evidence of hearing and acting on their particular need.

Provisions without provisions: occupational deprivation

Occupational instruments, outlined in the occupational justice framework, include services such as health, education, housing, transportation, employment and recreational facilities20. These topics are all mentioned in the disability policy. The discourse on occupational instruments and programmes in the disability policy carries some inherent conditions for occupational deprivation. The theme of provisions without provisions was informed by two categories, namely 'occupational deprivation in transportation' and 'occupational deprivation in health services'. For example, the policy on page 14 states that "public transport authorities shall: facilitate travel opportunities for passengers with disabilities by designing or adapting the various systems of public transport...."25:14. However, transportation of the public in Namibia is provided by privately owned transport businesses throughout the country, except in the capital city where the city of Windhoek has municipal buses that also provide transport to a small section of the public in Windhoek.

The decision to transport persons with disabilities thus resides with the taxi drivers. Anecdotal evidence reveals that usually taxi drivers will not want to transport persons with disabilities, particularly those with wheelchairs, during rush hour, because the drivers perceive it to be time wasting. In addition to this, persons with disabilities have to often pay double fees. They pay for themselves and their wheelchairs, and in the case of assistants, this is often triple the fee. Inaccessible transport for persons with disabilities significantly contributes to isolation and occupational deprivation because they are denied opportunities to reach schools, workplaces, and market places, for occupational participation.

Similarly, access to health services for persons with disabilities is considered free, but anecdotal evidence show that they do incur costs for transport, meals and accommodation if they are to visit a health facility. This may restrict other persons with disabilities from accessing the services that are considered free. There are more persons with disabilities in rural areas while rehabilitation services are located in urban areas, this implies travelling long distances and higher out-of-pocket costs associated with seeking health services for persons with disabilities.

Occupational inconsideration: a new form of occupational injustice

The vision, mission and objectives of the Namibia disability policy clearly show that the policy intentions are about enabling occupational participation of persons with disabilities. Some of the phrases to support this statement include:

"....towards a Society for All where all citizens can participate

in a single economy..."25:2. (Part of the Vision)

"... to improve quality of life through enhancing the dignity,

well-being.... enabling full participation, independence and

self-determination..."19:3. (Part of the Mission)

"... to enable people with disabilities to lead more independent and meaningful lives"25:3 (Part of the Development Objective)

"..Government will give priority to enabling people with disabilities to take charge of their lives by removing barriers to full participation in all areas..."25:3. (Part of the Guiding Principles)

However, the discourse within the policy becomes more non-specific and generalised, mentioning ideals without addressing occupational participation intentions. For example, on school participation for children with disabilities the policy states: "The Government shall ensure that inclusive schools recognize and respond to the diverse needs of their students...."25:6. This statement suggests that certain schools can respond to the needs of persons with disabilities, and that others do not need to thus hindering proper access for learners with more minor disabilities in mainstream schools.

If the challenges faced by persons with disabilities are not exacerbated in terms of occupational injustice, diversion from original policy intentions of ensuring occupational participation gets diluted or at worst, lost. The disability policy makes recommendations for the government to ensure that disability aspects are included in all relevant policy-making without adequately identifying the 'disability aspects' and the 'relevant' policies. This generalisation leaves room for avoidance of responsibilities because no specific role-players or stakeholders are identified. When a focus on enabling occupational participation is ignored, lost or is absent (due to the failure for policy-makers to adequately consider the occupational needs and consequences of people with disabilities), a new form of occupational injustice described as occupational inconsideration occurs.

This paper is the first to define occupational inconsideration as a phenomenon whereby the centrality of occupation is disregarded either knowingly or unknowingly, by those in authority or disability policy decision-making positions, such that the resultant policies are flawed in enabling occupational justice.

Findings on comparative analysis of southern African disability policies

Core factors included in the comparative analysis were: involvement of persons with disabilities in the policy formulation; disability model followed; lead ministry or custodian office; policy review status; and the disability movement situation. Results show a limited involvement of persons with disabilities in disability policy formulation in the southern African countries included in this study. The disability policy of Botswana uses a purely medical model for addressing disability; its name National policy on care for people with disabilities has negative connotations as it portrays persons with disabilities as dependent and needing help rather than being viewed from a human rights perspective38.

Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe, have disability policies/acts that have been in existence for 21, 22 and 26 years respectively. None have been reviewed, suggesting that disability issues are not considered a priority. Malawi and Zambia have not reviewed their respective disability policies; they however developed disability acts in a move to domesticate the UNCRPD39. South Africa has the most recent disability policy document i.e. a white paper that addresses that rights of persons with disabilities based on the UNCRPD. See Table IV on page 25.

Domestication of the UNCRPD in southern Africa

The UNCRPD provides a framework to create an occupationally just society for persons with disabilities. The occupational justice framework and UNCRPD are complementary in promoting participation of persons with disabilities in occupations of their choice and need. Namibia, South Africa, and Swaziland have signed the UNCRPD and its optional protocol. Zimbabwe has accessioned the optional protocol. Lesotho, Malawi, and Zambia have signed the UNCRPD, but not the optional protocol. Apart from Malawi and South Africa, all other southern African countries included in this study did not submit reports to the United Nations. Moreover, the respective reports submitted by South Africa and Malawi were overdue by four years. The report for Namibia is overdue by eight years; the main problem is insufficient technical capacity and minimal collaboration among stakeholders. This delay in submission of UNCRPD reports by southern African countries to some extent indicates lack of prioritisation to demonstrate domestication of the UNCRPD. Generally southern African countries are in a transitional phase moving from the medical and charity models towards the social and rights models, with South Africa demonstrating a leading role. An occupational justice perspective can be useful in enhancing the domestication of the UNCRPD for example through community based rehabilitation which is recognised as the operational strategy for the UNCRPD.

CONCLUSION

This paper has reviewed national disability policies in seven southern African countries, with a specific focus on Namibia. Although Namibia has an explicit national policy governing disability issues, it is evaluated as inadequate, based on the occupational justice framework The policy was flawed at its birth with no evidence of involvement of persons with disabilities. This sets the foundations upon which marginalisation, deprivation, alienation, and an absence of occupational consideration for participation of persons with disabilities in Namibian society are grounded. Furthermore, the language used in the policy is mostly vague, and non- specific, thereby enhancing the sense of disempowerment. Furthermore, the fact that the office for disability issues has been moved for the third time since its inauguration adds to the perception that disability has not been well understood and/or prioritised. By implication, the occurrence of occupational injustice thus has a fertile ground upon which to thrive. Domestication of the UNCRPD is in its initial stages in southern Africa. There is a need for policy-makers to always consider the facilitation of occupational participation of persons with disabilities when formulating disability policy in order to address occupational inconsideration and injustice that are evident in the current disability policy. Most importantly the right for persons with disabilities to be appropriately involved in decision-making on matters affecting their occupational participation, must be a pre-condition if conditions for occupational justice are to be more adequately met.

Implications

If disability policy formulation is to be adequately responsive to the needs of persons with disabilities then conditions for occupational justice need to be met. This can be achieved by disability policy formulation focusing on creating a conducive environment for persons with disabilities to participate in occupations that are meaningful to them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is part of a larger study conducted towards a PhD qualification by the first author, who was financially supported by the University of KwaZulu-Natal PhD Scholarship.

REFERENCES

1. Wilcock AA. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1999; 46(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.I440-1630.1999.00174.x. [ Links ]

2. Hammell KW. Reflections on well-being and occupational rights. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 75(1): 61-64. https://doi.org/10.2I82%2Fcjot.07.007. [ Links ]

3. World Federation of Occupational Therapy. WFOT Position Statement on Human Rights. CM2006 [home page on internet]. c2006 [cited 2015 Dec 13]. http://www.wfot.org/ResourceCentre.aspx. [ Links ]

4. Law M, Polatajko H, Baptiste W, Townsend E. Core concepts of occupational therapy. In: Townsend E, editor. Enabling occupation: An Occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa ON: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 1997:29-56. [ Links ]

5. Eide AH, Loeb ME, Van Rooy G, Fuller B. Living conditions among people with disabilities in Namibia. Pilot study. SINTEF Report STF78 A014502. Oslo: SINTEF Unimed NIS Health & Rehabilitation; 2000. [ Links ]

6. Townsend E, Wilcock AA. Occupational justice and Client-Centred Practice: A Dialogue in Progress. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004; 71(2): 75-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740407100203. [ Links ]

7. Wilcock AA, Townsend EA. Occupational justice. In: Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Boyt Schell BA, editors. Willard Spackman's occupational therapy. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams; 2009:192-199. [ Links ]

8. Wolf L, RipatJ, Davis E, Becker P MacSwiggan J. Applying an Occupational justice framework. Occupational Therapy Now. 2010; 2(1): 15-18. [ Links ]

9. Namibia. Ministry of Education. Sector Policy on Inclusive Education. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia; 2013. [ Links ]

10. Sankwasa F. Disability organisation wants own ministry. Namibian Sun. 2015 May: 21:3. [ Links ]

11. Mont D. Measuring Disability Prevalence. Social Protection discussion paper NO. 0706. Washington, D.C: World Bank; 2007. [ Links ]

12. United Nations.Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2006. [ Links ]

13. DPI. Proceedings of the First World Congress, Singapore: Disabled People's International; 1982. [ Links ]

14. Hughes B and Paterson K. (1997). The Social Model of Disability and the Disappearing Body: Towards sociology of impairment. Disability and Society. 1997; 12(3): 325-340. [ Links ]

15. Shakespeare T and Watson N. (1997). "Defending the Social Model." Disability and Society. 1997; 12(2), 293-300. [ Links ]

16. Mpofu E and Oakland T. Rehabilitation and Health Assessment Applying ICF Guidelines. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [ Links ]

17. Peterson DB and Elliott TR Advances in conceptualizing and studying disability. In Brown S and Lent R (Eds.). Handbook of counselling psychology (4th ed). New Jersey: Wiley; 2008: 212 - 230. [ Links ]

18. Elliott T, Kurylo M and Rivera P. (2002). Positive growth following an acquired physical disability. In Snyder CR and Lopez S (Eds.). Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002: 687 - 699. [ Links ]

19. Degener T. "A Human Rights Model for Disability," in Stein M and Lang-ford M (Eds). Disability Social Rights. Cambridge University Press; 2014. [ Links ]

20. Townsend E, Polatajko H. Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, & justice through occupations. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2013. [ Links ]

21. Kronenberg F, Pollard N. Overcoming occupational apartheid: A preliminary exploration of the political nature of occupational therapy. In: Kronenberg F, Alagado SS, Pollard N (Eds.). Occupational Therapy without Borders: Learning from the Spirits of Survivors. London: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:58-86. [ Links ]

22. Bond R McColl MA. A Review of Disability Policy in Canada, 2nd edition, Kingstone: Canadian Disability Policy Alliance; 2013. [ Links ]

23. McColl MA, Jongbloed J. Disability and social policy in Canada. Toronto: Captus Press; 2006. [ Links ]

24. Pereira RB. Book review: Theorising social exclusion. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009; 17(3): 191-191. [ Links ]

25. Namibia. Ministry of Lands Resettlement and Rehabilitation. National Policy on Disability. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia; 1997. [ Links ]

26. Horkheimer M. Critical Theory. New York: Seabury Press; 1982. [ Links ]

27. Charlton J. Nothing about us without us. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1998. [ Links ]

28. Held D. Introduction to critical theory: Horkheimer to Habermas. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1980. [ Links ]

29. Bacchi C. Analysing Policy: What's the problem represented to be? Frenchs Forest NSW: Pearsons Australia; 2009. [ Links ]

30. Eldridge V British Columbia (A.G.), 3 S.C.R. 624 [Eldridge] 1997. [ Links ]

31. Michalko R. The Difference That Disability Makes. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press; 2002. [ Links ]

32. Chilton P. Analyzing Political Discourse - Theory and Practice. London: Arnold; 2004. [ Links ]

33. Namibia National Planning Commission. National Population and Housing Census. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia; 2012. [ Links ]

34. Southern Africa Federation of the Disabled. About the National Federation of People with Disabilities in Namibia (NFPDN) [homepage on the internet]. No date [cited 2016 Jan 6]. Available from: http://safod.net/namibia.html. [ Links ]

35. Namibia. Ministry of Health and Social Services. Health and Social Services Review. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia; 2008. [ Links ]

36. Corsino BV What's the only word that means mandatory? Here's what law and policy say about "shall, will, may and must." No date [cited 2016 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/plain_language/articles/mandatory/. [ Links ]

37. Charrow VR, Erhardt MK, Charrow RP. Clear & Effective Legal Writing. New York: Aspen Publishers; 2007. [ Links ]

38. Botswana, Ministry of Health. National Policy of Care for People with Disabilities. Gaborone: Republic of Botswana; 1996. [ Links ]

39. Malawi. Ministry of Persons with Disabilities and the Elderly. National Policy on the Equalisation of Persons with Disabilities. Lilongwe: Government of Malawi; 2006. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Tongai Fibion Chichaya

chichayatf@gmail.com