Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.48 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol48n3a7

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

The facilitators and barriers encountered by South African parents regarding sensory integration occupational therapy

Jacintha SmitI; Jo-Celene de JonghII; Ray Anne CookIII

IBSc (OT) Wits, Post Grad Diploma in Advanced Occupational Therapy (Wits), M OT (Stell)- Postgraduate student, Department of Occupational Therapy University of Stellenbosch. Private Practitioner, British Columbia, Canada

IIB OT (Stell), MPhil Education (UWC), PhD (UWC) - Deputy Dean Learning and Teaching, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

IIIM OT (Stell) - Private Practitioner, Sensory Kids Zone, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Differences in parent perceptions regarding occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach to treatment have been noted. The various factors that may influence these perceptions, and how the perceptions may ultimately influence the outcome of the intervention for the child and family were questioned. A phenomenological study revealed a progression that all parents perceived and experienced as the "before", "input" and "after" phases of when their child received occupational therapy/sensory integration (OT/SI). This article focuses specifically on the "input" phase of OT/SI intervention.

METHOD: Participants in this study were nine parents of children with difficulties processing and integrating sensory information, who live in the Western Cape, South Africa. Using a qualitative, phenomenological approach, data were collected during face-to-face interviews, participant observation and researcher's field notes

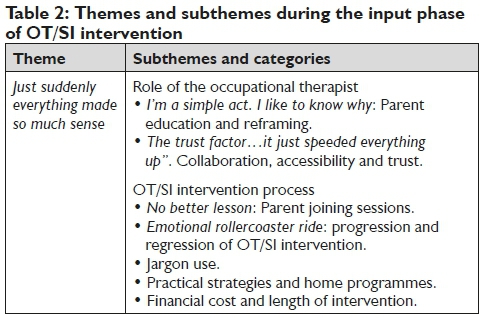

FINDINGS: The main theme related to this phase of analysis was "Just suddenly everything made so much sense". For most participants, this phase brought to light a better understanding of sensory integration disorder (SID), also known as Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) and OT/SI. Data analysis identified two subthemes that catalysed expansion in most participants' understanding, which were the role of the occupational therapist, and the OT/SI intervention process. Within these subthemes, the facilitating factors and barriers of OT/ SI intervention emerged

CONCLUSION: Insight gained from the participants' recommendations and interpretation of findings allowed recommendations to be made within the OT/SI intervention received, in an attempt to overcome the barriers and promote the facilitators that will make a difference to OT/SI in South Africa

Key words: Sensory integration; sensory integration disorder (SID); sensory processing disorder (SPD); parent(s) perceptions; facilitators; barriers

INTRODUCTION

The need to explore why some parents of children with sensory integration disorder (SID) receiving occupational therapy/sensory integration (OT/SI) do not perceive positive outcomes of the intervention has been addressed by Cohn in the United StatesI. She considered whether or not parents' perception was based on their child's actual performance or on their expectations of OT/SI. Her study emphasised how parents make sense of what is occurring in and as a result of the intervention as previous studies on parent perspectives of OT/SI had focused specifically on the outcomes of the intervention only1. It has been recommended that the broader context surrounding OT/SI be further explored, as this may impact the intervention. This prompted the exploration of facilitators and barriers encountered by parents in the Western Cape in South Africa that may influence the outcomes of OT/SI for the child and family.

Three progressive phases were identified in a phenomenological study which addressed the following research question: How do parents perceive and experience OT/SI as an intervention approach to improve their child's occupational performance within a South African context? All parents encountered "before", "input" and "after" phases and this article focusses on the "input" phase of the intervention that addressed: the facilitators and barriers of OT/ SI as an intervention approach encountered by parents. Based on the findings of the study, recommendations were made to ensure the delivery of OT/SI intervention meets the needs of parents and their children in South Africa.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Parent Education and reframing

Bundy described "reframing" as a process that allows others to understand a child's behaviour in a new way or from a different perspective2. She describes how by using sensory integration theory to reframe, parents are provided with a basis for developing different strategies for interaction with their children2. In a study by CohnI on parents' perspective and experience of OT/SI, parent education and reframing emerged as facilitating factors in terms of the participants' perceptions and experiences of OT/SI. These were considered as the strongest findings regarding parent-focused outcomes and participants in her study reported many benefits associated with reframing, such as understanding their child's behaviour through sensory integration lenses. Cohn's study also described the link between parent reframing and reconstruction of the child's sense of self-worth1. As parents' understanding of their children's behaviour from a sensory integration perspective changed, they became more accepting of their children which they believed further facilitated their children's sense of self-worth1. Participants further described how reframing enabled change in three areas: a shift in their understanding and expectations of their child and themselves as parents; validation of parenting experiences; and the ability to advocate for their child within the school context1.

A recent South African study on parents' experiences with regards to tactile defensive children who are treated using OT/SI, found that parents shared their own coping abilities, which were enhanced by parent education as one facilitating factor, amongst others, in the management of tactile defensiveness3. Insight gained from this study emphasises the need to educate parents regarding tactile defensiveness from a multidisciplinary team approach including occupational therapists and psychologists, and how this may influence intervention and management of the condition.

Parent-professional collaboration

The development of a collaborative relationship between parent and occupational therapist in intervention for children with learning difficulties or developmental delay is stressed both in the literature and based on the clinical experience of Anderson and Hinojosa4. The importance of occupational therapists working collaboratively with parents to ensure the service meets the child and family's valued needs is also a common recommendation in previous parent perspective studies on OT/SI1,5,6 and in other populations7. When using OT/ SI, communication with parents is a structural element measured on the Ayres Sensory Integration Fidelity Measure©8. This involves parent collaboration in goal setting and education regarding the influence of sensory integration on valued activities and participation in contexts such as home, school and the community7. Literature indicates however that it is possible that various enabling or inhibiting factors may have influenced this parent-occupational therapist relationship and its impact on the participants' perceptions and experiences of OT/SI1.

Therefore, the recommendations of Anderson and Hinojosa4 that occupational therapists (1) recognise the important role parents play in the therapeutic intervention, (2) understand parent-child interaction and (3) include successful parent collaboration to provide an intervention that benefits the child, have to be considered. The authors propose that the primary goals of intervention when working with parents are to develop an effective working relationship between parent and occupational therapist, and to facilitate satisfying parent-child interactions that will foster this relationship and the child's further development4. In order to achieve this, occupational therapists need to consider the past- and present factors that may influence the parenting process and the parents' main concerns regarding their child's performance. The parenting roles and functions; and "stage-related parental reactions"4:455, which describe the effects a child's poor performance or delay may have on a parent at each stage of the child's development, should also be taken into account.

A rationale in support of a parent-professional partnership when working with children who have challenging behaviours (including destructive, disruptive or interfering/stigmatising behaviours), was presented by Dunlap and Fox9. In their experience, a partnership between parent and professional requires commitment from both parties, a joint vision, mutual trust, communication, respect and understanding of each party's contexts and roles9. Furthermore, they describe that for this partnership to be effective, commitment from the parent must fit with the professional's availability. Expanding on the trust factor, the authors describe this as a fundamental part of the parent-professional partnership, which stems from time spent with the family, developing relationships and demonstrating genuine caring and commitment to the child's needs9.

Other factors related to parent-occupational therapist collaboration perceived as having a facilitating influence and instilling hope for parents to construct an optimistic narrative regarding their child's lives was reported in a case report by Holzmueller10. These include: collaborative assessment, information provided to parents that is accurate and realistic, recognition of the uncertainty of data and its implications for the child's life, minimised use of jargon, and by involving parents in treatment planning and providing them with options regarding intervention.

This collaboration should be continued when a home programme for parents and their children is prescribed by occupational therapists as it may be perceived by parents as either a facilitator or barrier to the outcomes of the intervention. Working collaboratively to develop effective home programmes means the parent and occupational therapist share information to identify the best intervention activities for the child and family11. Bazyk11 suggests that the degree and type of collaboration is however, dependent on a parent's preference for participation and changes within the contexts of their lives.

Parent-to-parent support

According to Cohn5 a perceived facilitator encountered by parents of children receiving OT/SI at a private clinic in the United States which they valued was the support they received from interactions with other parents in the waiting room of the OT/SI clinic. Interaction with other parents in similar situations allowed for the natural development of support for the parents of children with SID through sharing of their experiences, stories, challenges, and resources. This interaction moved participants from a place of isolation to the "threshold of waiting for some type of transfor-mation"5:170.

Reframing of themselves and their children in this context occurred when participants compared their own child's occupational performance to others also receiving OT/SI intervention5. This implies that as occupational therapists we need to pay attention to the entire context surrounding OT/SI intervention and how this may impact perceived change and experiences for parents. Cohn5 points out that parent-to-parent support also sheds light on and considers the broader environmental context within which intervention occurs and how this influences parents' perceptions and experiences of OT/SI intervention.

Within a South African context

A report in a South African newspaper gave a rich, contextual glimpse into possible socio-cultural factors and contexts that may be relevant to South African parents' perceptions and experiences of OT/SI12. In her article Grange12 reports on interviews with parents of children who accessed occupational therapy, reflecting both positive and negative accounts. Amongst these accounts, factors such as financial constraints, length of intervention, changes perceived in the child's abilities and activities, and parent-occupational therapist collaboration appeared to influence parents' perceptions and experiences of occupational therapy services. The author alludes to OT/SI in her article and the contextual factors that may impact a child's occupational performance in South Africa, which include a society of high stress created by pressures to perform, crime, exposed toxins, absence of parents due to work, large number of children in classroom settings, and an increase in sedentary activity such as watching TV and playing computer games12,13. This article provides some understanding of the South African socio-cultural milieu in which parents and their children with SID participate.

METHODS

A qualitative, descriptive, phenomenological research design was selected to address the research question: How do parents perceive and experience the facilitators and barriers of OT/SI as an intervention approach? This design was used to provide rich descriptions and vicarious experiences of what it was like for participants as parents of a child with SID receiving OT/SI in South Africa.

Population

Purposive sampling was used to select nine parents, between the ages of 36-41, of children with SID, who live in various suburbs of the Western Cape, South Africa (see Table 1, page 46). The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were employed based on criteria used by experts in the field of parent perspective studies of OT/SI intervention1.

Inclusion criteria

❖ Parent(s) of children with a documented diagnosis of some type of disordered sensory integration, who receive or have been discharged from intervention in private practice, conducted by a sensory integration trained occupational therapist who meets the Ayres Sensory Integration® Fidelity Measure©.

❖ Parent(s) of children age 4 - 10 years since The Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT) provides standard scores for children between the ages of 4 years and 8 years 11 months of age14

❖ Parent(s) from the Western Cape, South Africa.

❖ Children who have participated in approximately eight months of OT/SI intervention as recommended by Cohn to anticipate some form of change1.

Exclusion criteria

❖ Parents of children with a primary diagnosis of autism, pervasive developmental disorder, fragile X syndrome and cerebral palsy, as these children may present with social-emotional and behavioural dysfunction different to children without these conditions.

❖ Parents of children who received or are receiving other therapies that may influence their behaviour such as play therapy, psychotherapy or behaviour intervention.

Prior to participant recruitment, sensory integration-trained occupational therapists in the Western Cape received a letter explaining the purpose of the study and informing them of the Ayres Sensory Integration® Fidelity Measure©. The purpose of this measure ensured that intervention provided by the occupational therapists adhered to the sensory integration theory and principles developed originally by Dr. A. Jean Ayres. Nine occupational therapists willing to participate were assessed by a certified occupational therapist using this tool. Seven occupational therapists who met the standard for OT/SI were then approached for referral of the participants who were included in the study. The referring occupational therapists introduced the purpose of the study to the parents and forwarded the contact details of those parents interested in participating to the researcher. To answer the research question, the following methods of data collection were used in this study: face-to-face interviews, participant observation and researcher's field notes.

Eight interviews were conducted twice over a period of three months, and analysed until data saturation was reached. The first parent interviews were conducted in the participants' homes. These ranged from 45 minutes to an hour. During the second data collection phase, parent interviews and member checking were conducted via Skype™.

Data analysis

Creswell's multiple levels of analysis was employed during qualitative data analysis15 and included: organising and preparing the transcribed interviews; notes of observations during interviews and field notes; reading through the data to gain a "general sense" of the data; manual analysis of the interviews using a coding process; generation of themes and sub-themes; representation of the data into a narrative, tables and figures; and lastly data interpretation in the final stage of analysis. To ensure that trustworthiness and rigor were maintained, the Lincoln and Guba's model of criteria was used, as cited in Krefting16, which consists of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability. Relevant ethical clearance was obtained from the university ethics committee and through out the methodology, three fundamental ethical principles were used to guide this research: respect for persons, beneficence and justice and..

FINDINGS

The theme Just suddenly everything made so much sense emerged from data analysis and describes the progression of the participants' perceptions and experiences during the intervention or "input" phase. (See Table II page 47) Data analysis identified two subthemes that catalysed expansion in most participants' understanding. These included: the role of the occupational therapist and the OT/SI intervention process.

1. Role of the occupational therapist

The occupational therapist facilitated participants' awareness and understanding of SID and OT/SI. The relationship between the participants and occupational therapist emerged as a facilitating factor in most participant's experience of OT/SI and is portrayed in two different categories: parent education and reframing, as well as collaboration, accessibility and trust for both parent and child.

I'm a simple act. I like to know why: Parent education and reframing

The role of the occupational therapist as perceived by participants was a common facilitator of parent education and reframing. The occupational therapist explained information in a new and different way that helped Gill as a parent understand SID and therefore her child's occupational performance better. For Louise, this reframing was described as follows:

It just opened my world to seeing why she's got some of the problems or why she's struggling to cope (Louise, mother).

With this new understanding, she realised that her child was the "perfect candidate" (Louise, mother) for OT/SI intervention. Ilze said she has always recognised that children are different and that these differences should be respected, however, it was only after OT/SI education and reframing that she understood these differences from a sensory integration perspective. Suzanne's example describes how a new understanding of SID, OT/SI and her child prepared her child's team and gave them a sense of direction:

And as soon as we knew what it was, everybody could be mobilised. So the teachers were mobilised to know what to do, where to put her in class, how to treat her when she's anxious and all these things. So, to me, it's the most wonderful thing knowing what's happening (Suzanne, mother).

In one case, parent group meetings, as organised by the occupational therapist, not only increased Candice's understanding of SID and OT/SI, but also gave her a sense of hope, community and information sharing.

On the other hand, one participant's story illustrates a contrasting perspective where the relationship with the occupational therapist emerged as a barrier. At the first interview, Tia desired more information and education from her child's occupational therapist regarding OT/SI intervention, as she felt incompetent explaining or advocating for her child's occupational performance from a sensory integration perspective to other people in various contexts such as family or at school. Tia's poor understanding of the intervention meant that she and the occupational therapist had different expectations of her child's performance during assessment. This created a barrier, which was the final straw in ending OT/SI intervention for her and her child.

The trust factor...it just speeded everything up: Collaboration, accessibility and trust

Of the participants who perceived and experienced a positive relationship with their child's occupational therapist, three categories emerged: parent-occupational therapist collaboration; occupational therapist accessibility; and trust in the occupational therapist for both parent and child. In these cases, collaboration meant a partnership between participants and the occupational therapist that echoed a close, warm and supportive relationship with open communication and information sharing:

Whenever there was a problem, I knew I could ask her and find out more things. (Candice, mother).

As a father of a child receiving OT/SI, Stefan found the feedback he received from the occupational therapist, regarding his child's progress, to be helpful. It reassured him that the intervention was working and thus financially viable.

Participants valued the occupational therapist's accessibility during everyday situations that a parent of a child with SID faces. This accessibility gave them a sense of support:

The OT has been great because she has been a phone call away. And I would often phone her and say this is happening and you know, maybe you can explain it to me, and she does, and I think, oh, that makes perfect sense. (Gill, mother).

Trust in the occupational therapist for both parent and child appeared to be a factor that fortified the participants' relationship with the occupational therapist and facilitated their perception of OT/ SI. Candice shared how the trust factor accelerated her child's occupational performance: I think what it did for him, the trust factor... it just speeded everything up (Candice, mother). Many participants shared their gratitude for their child's occupational therapist who they trust and connect with, and this put them at ease. Trust is the major thing (Stefan, father) for the parent couple interviewed. The significance of these words suggests their firm belief in the truth, reliability or ability of their child's occupational therapist and the OT/SI intervention process.

We've got the world of confidence in our OT so I left it to her...and then this process because we know SI.and our OT is a professional. She would know and we trust her. (Stefan, father).

Karlien, the mother, added: "That's why I feel the relationship with the OT is so important because...she's [the child] built this relationship with her OT, so that's why the confidence is there and why she feels she can actually go to the next level".

2. The OT-SI intervention process

This subtheme explores the perception of the actual OT/SI intervention sessions and strategies received by participants and their children. It describes the facilitators and/or barriers to their overall experience.

"No better lesson": Parent joining sessions

Seven participants joined their child's OT/SI sessions, which emerged as a facilitating factor in their understanding of OT/SI and their child's occupational performance. Ilze drove long distances weekly to attend these sessions with her child, as for her there is "no better lesson".

"Emotional rollercoaster ride": progression and regression of OT/SI intervention

Barriers mentioned by some parents were their perception that the actual OT/SI sessions were exhausting for their child, resulting in unexpected behaviours at home. In such cases, participants were uncertain of the after effects of an OT/SI session on their child's performance, and how to manage this at home. One participant explained how as her child got older, he perceived his OT/SI sessions as tedious, while another mentioned that although she learnt a lot by observing her child's OT/SI sessions, she would have benefited from a break at times. It seems this need for a break may link to the emotional rollercoaster ride participants perceived. A few participants mentioned the ups and downs of their child's progression and regression during OT/SI intervention:

Sometimes it feels like things are getting worse before they get better. (Suzanne, mother).

This was perceived as an emotional rollercoaster ride (Gill, mother) of joy and elation on one day, and sadness the next. One participant's perception and experience of this progression and regression made her doubt the benefits of the intervention even more.

Jargon use

The use of jargon when discussing therapy and progress was identified as a barrier

I always think of someone who doesn't have any medical background, just the word 'sensory' is weird...doesn't mean anything to them. (Louise, mother).

Practical strategies and home programmes

Practical strategies for home and other contexts recommended by the occupational therapists were perceived as helpful and empowering for most participants. These strategies equipped participants to support their child at home and in other contexts, such as birthday parties, shopping malls or community outings. However, some participants described home programmes as time consuming and exhausting. One participant experienced home programmes as an added pressure and felt guilt as a parent if they were not carried out. Although another's experience of home programmes corresponds with the above, she committed to it as she saw improvements in her child's occupational performance, and was happy with the end results.

Financial cost and length of intervention

Some participants mentioned the financial aspects/implications of OT/SI intervention in South Africa. In one participant's experience it is financially tough to afford interventions and private schooling to meet her child's needs. Despite this and together with her husband, they are prepared to give up other luxuries in life to afford OT/SI intervention for their child. As a father, the participant explained how OT/SI is financially worth it. This is based on his perceptions and experiences of his child's progress and their relationship with the occupational therapist. In contrast, one participant decided that a lot of money was spent on a service that didn't meet the family's needs and thus discontinued the intervention. During the first interviews it became apparent that some participants experienced OT/SI intervention as a lengthy process, and the length and unpredictability of the intervention was a big frustration.

DISCUSSION

Key points of change during input of OT/SI intervention for all participants were closely examined. From their accounts, specific facilitators were identified that appeared to enhance their perceptions and experiences of OT/SI intervention as a treatment approach in improving their child's occupational performance.

The parent-occupational therapist relationship as a facilitator

Eight out of nine participants perceived their collaboration with their child's occupational therapist to be a facilitator in their experience of OT/SI intervention. Closer analysis revealed the facilitating influence of the occupational therapist was portrayed in the following four areas: parent education and reframing; collaboration between participant and occupational therapist; accessibility of occupational therapist to participant; and trust in occupational therapist for child and participant.

Parent education and reframing

For most participants, the occupational therapist increased parent awareness and understanding of SID and OT/SI intervention by explaining their child's occupational performance in a new and different way that made sense to them. Bundy2 proposes that reframing can help parents understand their child, develop successful strategies to interact with them and thus promote rewarding parenting experiences. As a result of reframing, participants described the shift in their understanding and expectations of their child's occupational performance during the "after" phase of OT/SI intervention. Reframing also facilitated change in themselves as parents with regards to validating their parenting experiences, empowerment, feelings of relief and joy, and being able to advocate for their child in different contexts. These findings are similar to one of the strongest findings in Cohn's study, in which parents benefited from understanding their child's behaviour from a sensory integration perspective1. Cohn1 found her participants' shift in expectations for themselves and their children, validation of their parenting experiences and advocacy for their children to be by-products of reframing. Cohn's notion of the by-products of reframing can be accepted in this study, as it is reflective of the participants' new and better understanding of their child. These findings are also consistent to those in the study on the experiences of parents of children with tactile defensiveness3.

Collaboration

Collaboration between the participants and the occupational therapist was identified as a facilitating factor of OT/SI intervention. Collaboration meant a partnership between participants and the occupational therapist that was a close, sincere and supportive relationship with open communication and information sharing. Open communication between therapist and parent comes from a relationship where the parent feels comfortable to ask questions or express concerns freely4. One participant described collaboration as extending beyond the relationship between her and the occupational therapist, as it also means being part of the team of professionals at her child's school including the occupational therapist.

Accessibility

Some participants valued the occupational therapist's accessibility during everyday situations. Not only does accessibility mean approachable and easy-to-talk-to in the traditional sense of the word, it is also used to describe accessing a service, for example: some parents described phoning their child's occupational therapist whenever they were concerned about their child's performance, while another parent described how the occupational therapist met the child and family at the child's future school playground to provide OT/SI intervention there and facilitate the transition for the child. This accessibility provided a sense of direction and support, which seemed to put the participants at ease. This appears to have provided further opportunities for reframing and parenting empowerment, and the support facilitated participants' emotional feelings of relief and joy, described by parents during the "after" phase of OT/SI intervention.

Trust

"Foster therapeutic alliance"17:219, is a core element of the OT/SI intervention process and describes the occupational therapist-child connection in an environment of trust and emotional safety. Participants' stories highlight the influence of this trust in the occupational therapist regarding their child's occupational performance and described it as the major thing (Stefan, father). The significance of these accounts suggests the participants' and their children's firm belief in the truth, reliability and ability of the occupational therapist and OT/SI intervention process.

The facilitators within the OT/SI intervention service

Common facilitators within the OT/SI intervention service received by parents and their children were examined. These included: parents joining their child's OT/SI intervention sessions and practical strategies recommended by the occupational therapist for the home and other contexts. It appeared that facilitators within the OT/SI intervention process were influenced by the parent-occupational therapist relationship as described above, for example collaboration between participant and occupational therapist meant better implementation of practical OT/SI strategies at home for participants and their child.

Parents joining child's OT/SI intervention session

Joining OT/SI sessions appeared to be an opportunity for participants to further collaborate with the occupational therapist and broaden their understanding of OT/SI intervention and their child. This also in turn influenced their ability to carry out strategies with their child at home, boosting parent empowerment and parenting experiences. In the context of this study, it was very common for both parents to work, thus limiting this opportunity to join sessions. The "parent helping parent" approach has been successful in many programmes, where parents facing similar problems share and problem-solve together4. For one participant and her husband, parent group meetings not only supplemented their understanding of OT/SI intervention and their child, but also gave them a sense of hope, community and information-sharing from one parent to another. Similarly, participants' experiences in the waiting room in Cohn's study revealed the support from each other by sharing stories, challenges, experiences and resources as parents of a child with SID5.

OT/SI strategies for home and other contexts

Strategies for home and other contexts developed from collaboration between participant and occupational therapist were perceived as helpful and empowering for eight participants. It appeared that participants valued the practical strategies they could employ during activities of everyday life, the tiny little things that made such a difference (Gill, mother). This speaks to the recommendations regarding parent-occupational therapist collaboration made in previous parent perspective studies1,5,6 and that by including successful parent collaboration, occupational therapists can provide intervention that benefits the child4.

Barriers of OT/SI intervention during the input phase

All participants, including those who had an overall positive experience of OT/SI intervention, perceived or experienced some barriers with regards to OT/SI in South Africa. These barriers fall within two categories: parent-occupational therapist relationship and procedural.

Parent-occupational therapist relationship: poor collaboration, accessibility and trust

For one participant, the parent-occupational therapist relationship appeared to be the most prominent barrier in her perceptions and experiences of OT/SI. From Tia's narrative, her relationship with her child's occupational therapist lacked the parent education and reframing, collaboration, accessibility, and trust, which appeared to be the main facilitating factors in the other participants' perceptions and experiences of OT/SI intervention. A poor understanding of OT/SI and her child influenced her parenting experience in different contexts with regards to feelings of emotional distress and incompetency as a parent.

To ensure successful parent-occupational therapist collaboration, occupational therapists need to employ a collaborative model when working with children and their parents. This means occupational therapists need to assist parents in acquiring knowledge and skills to better manage their child's challenging behavior11. Also, occupational therapists need to be aware of the different and intricate feelings parents bring to the parent-occupational therapist relationship that are related to personal, family and work aspects of their lives4. These feelings may be associated with parent denial or acceptance of diagnosis, or overwhelming feelings associated with impairment, that may influence their engagement in the therapeutic process4. Considering these factors, as well as others that may influence the parent-occupational therapist relationship i.e. commitment, joint vision, mutual trust, communication, respect and understanding of each party's roles and contexts9, it is possible that Tia's perceptions and experiences of OT/SI may have been different should these factors have been considered at the start of intervention.

Procedural barriers

The word "procedural" has been used to describe barriers perceived and experienced by participants within the OT/SI intervention, as it speaks to the obstacles in the intervention procedure/ practice provided to participants and their children. Analysis revealed that issues such as jargon use, home programmes, unpredictability and length of intervention, and meeting the "just right challenge" for the child, fall within this category. Many of these barriers were raised by the participants as recommendations to improve OT/SI intervention for South African children and parents.

Jargon use

The use of OT/SI jargon during parent education or reframing, or in OT/SI assessment reports was perceived as a barrier for some of the participants. Louise, a mother and physiotherapist with a medical background, felt the use of jargon may be meaningless to other parents, like Tia, who don't have this background. Unable to understand or explain their child's occupational performance in a simple way to others, may have fed into emotional feelings such as frustration and anxiety, as well as the parenting experience of incompetence in social contexts.

Home Programmes

Three participants described home programmes as time consuming and exhausting. Although all these participants' perceived the role of the occupational therapist with regards to parent-occupational therapist collaboration as a facilitator and recommend OT/SI intervention as a treatment approach, there appears to have been a gap in this collaboration for these participants to feel this way. Bazyk11 writes that to truly value collaboration between therapist and parent, both partners need to share unique information to develop a home programme that best identifies the needs of the child and family. Furthermore, Bazyk adds that when using a collaborative approach in developing a home programme, the therapist should not prescribe activities nor blame the parent for not carrying out these activities11.

Achieving the "just right challenge" in OT/SI sessions

One participant described that after a while OT/SI intervention became tedious for her child as he got older, resulting in him not wanting to participate in the intervention. One of the fundamental elements of OT/SI intervention process is to provide just right challenges8. This means occupational therapists need to adapt activities within the session that challenge the child, thereby providing opportunity for adaptive responses to sensory input and motor plan-ning8. A core element of the OT/SI intervention process that may apply here is "creates a context of play by building on the child's intrinsic motivation and enjoyment of activities"8219. As occupational therapists we are challenged to adhere to these elements of OT/ SI intervention as the child's adaptive responses improve and as their intrinsic motivation changes with age. This may account for perceptions regarding sessions as "tedious" or "boring". In contrast, some participants described OT/SI sessions as exhausting for their child. In this context, it is possible that the activities in session may have been perceived as too challenging.

Recommendations within OT/SI intervention received

These recommendations pertain to the OT/SI intervention received by parents and children in South Africa, and include the parent-occupational therapist relationship and procedures used by therapists. The facilitators of OT/SI intervention that emerged from the theme and subthemes in the findings form the basis upon which these recommendations are made.

Power of the parent-occupational therapist relationship

The role of the occupational therapist in the parent-occupational therapist relationship is one of the most powerful factors in facilitating OT/SI intervention for parents and their children. This study recognises the influence of the occupational therapist in parent education and reframing, collaboration, accessibility, and trust. All four aspects facilitated change perceived by participants in their child and themselves as parents after OT/SI intervention i.e. better understanding and expectations of their child, and parent empowerment, validation and advocacy. It is recommended that the parent-occupational therapist relationship be regarded as important as the child-occupational therapist relationship and a collaborative approach be adopted to facilitate OT/SI intervention. A possible strategy to promote this is regular parent meetings. It is suggested to use a child's OT/SI session for parent intervention if scheduling issues reduce parent-occupational therapist contact8. Meetings allow opportunity for parent education and reframing.

These meetings also open up the chance for validation of parenting perceptions and experiences. From this it is possible that barriers perceived by the participants, such as: unclear parent expectations; poor understanding of OT/SI assessment and goal setting; the "just right challenge" during sessions; the latent effects of OT/SI sessions on their child's performance; and the length of intervention, can be addressed. Additionally, with regards to assessment and goal setting, CohnI proposes that at the onset of evaluation, parents and children should be asked questions regarding the social world in which they live, work and play, and recommends focusing on the child's everyday life as the starting point of assessment. Reference is made to the top-down approach of evaluation as recommended by Coster18. A top-down model for assessment seeks to make intervention more valuable to parents and their children as it regards the child's successful occupational performance in valued roles and contexts as an outcome of intervention18.

Parent group meetings

Taking into consideration one parent's perceptions of parent group meetings and Cohn's5 previous research regarding the benefits of parent-to-parent support and information sharing, it is possible that this approach could address some of the barriers mentioned above as well as further promote parent education and reframing. Parent-to-parent support during group meetings also offers working parents, who are unable to attend OT/SI sessions, an opportunity to actively engage in promoting their child's occupational performance. These could be held every other month in the evenings or on weekends when working parents are able to attend.

Practical strategies for home

Many participants valued practical strategies that empowered them to handle their child's occupational performance at home and in other contexts such as dealing with a melt down at a birthday party. However, these can also be perceived as time consuming and exhausting if they don't fit into the daily routine of a family's life. From this study, one is aware of the emotions parents of a child with SID experience and how these reflect their own feelings of parent competency.

Home Programmes

Home programmes should not increase any feelings of guilt, self-blame or failure for the parent. BazykII provides six guidelines to promote collaboration between parent and therapist when developing home programmes for the child and family that are practical to the family's daily routine:

❖ respecting parents in their decision making regarding their child and family; acknowledging all the roles associated with being a parent such as caregiver to other children, homemaker, worker etc. and how this impacts a realistic home programme; working collaboratively with parents in developing a home programme that best fits the daily lives of the child and family;

❖ accepting that all families are different and parent participation in home programmes is dependent on this;

❖ offering parents and the child different options regarding activities recommended for home; and to always consider the child, and their occupational roles, as part of the family unit11.

Strategies to make OT/SI intervention understandable to parents and others

Considering the perceptions and experiences of participants regarding the awareness of OT/SI in South Africa, it is not surprising that OT/SI terminology or jargon can seem unfamiliar and confusing. If we are to truly work with parents collaboratively with the intention of empowering them to best support their child's occupational performance, it is recommended therapists refrain from jargon that hinders parent's understanding of OT/SI and their child. Therapists need to be able to explain to parents, teachers and others how sensory integration relates to the everyday occupational performance of a child. Royeen and MarshI9 gave examples of how OT terminology can be made more understandable to parents and teachers in a school context, for example: they revised the traditional terminology of "improve sensorimotor integration function" to "improve ability to receive, process and use sensory information to allow for more normal environmental interaction"19:714. Sensory integration trained occupational therapists need to develop such examples of OT/SI intervention terminology and how that relates within the context of a child's occupational performance.

IMPLICATIONS

This study contributes to the understanding of South African parents' perceptions of OT/SI intervention as a treatment approach in improving their child's occupational performance. Recommendations were based on the facilitators and barriers perceived and experienced by participants themselves, as well as those identified through interpretation of the findings. These may provide the starting point for change at two different levels i.e. at an organisational level, such as South African Institute for Sensory Integration (SAISI)©, as well as at a therapist level. This article focuses on the recommended changes at therapist level i.e. occupational therapists may shift their approach in how they provide this service to parents and children, bearing in mind the power of parent-occupational therapist collaboration in improving a child's occupational performance.

It is necessary to identify and acknowledge the limitations of the study that may have influenced the interpretation of findings. The sample consisted of parents who were all Caucasian, from middle to affluent socio-economic classes, either Afrikaans or English speaking and mostly mothers. Considering the multi-racial and multi-cultural background of South Africa, this sample is not representative of the population. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study narrowed the number of referring occupational therapists for the study, as these occupational therapists had to meet the standards of the Ayres Sensory Integration Fidelity Measure© prior to referral of potential participants. The inclusion and exclusion criteria also limited potential participants, as many children with SID engage in multiple therapies such as play therapy, and children below the age of four and above the age of ten years were excluded. The second participant interviews were conducted via Skype™. Although these interviews were conducted in the privacy of the participants' homes and were recorded by video to provide a visual for participant observations, the researcher was not physically present in the natural setting as recommended by Creswell20. Conducting interviews via Skype™ also opened the opportunity for technical difficulties. During the interviews, information shared by participants was taken by face value. During all the interviews, the researcher aimed to be open-minded, approachable, non-biased and trustworthy so that participants felt comfortable to share their stories.

This study was confined to the geographical constraints of the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to the whole population of parents of children between the ages of four to ten years who have received OT/SI intervention in South Africa. Rather, regarding transferability in qualitative studies, results from this study can be supported by or guide future research studies regarding OT/SI in South Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Members of the South African Institute for Sensory Integration (SAISI©) board for their financial assistance.

REFERENCES

1. Cohn ES. Parent perspectives of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001; 55(3): 285-294. [ Links ]

2. Bundy AC, Lane SJ, Murray EA. Sensory Integration Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F A. Davis Company; 2002. [ Links ]

3. Spies R, van Rensburg E. The experiences of a group of parents with tactile defensive children. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 42(3): 7-11. [ Links ]

4. Anderson J, Hinojosa J. Parents and therapists in a professional partnership. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1984; 38(7): 452-461. [ Links ]

5. Cohn ES. From waiting to relating: parents' experiences in the waiting room of an occupational therapy clinic. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001; 55(2): 167-174. [ Links ]

6. Cohn E, Miller LJ, Tickle-Degnen L. Parental hopes for therapy outcomes: Children with sensory modulation disorders. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000; 54(1): 36-43. [ Links ]

7. Carman SN, Chapparo CJ. Children who experience difficulties with learning: Mother and child perceptions of social competence. The Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2012; 59(5): 339-346. [ Links ]

8. Parham LD, Cohn ES, Spitzer S, Koomar JA, Miller lJ, Burke JP et al. Fidelity in sensory integration intervention research. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007; 61(2): 216. [ Links ]

9. Dunlap G, Fox L. Parent-Professional Partnerships: A valuable context for addressing challenging behaviours. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2007; 54(3): 273-285. [ Links ]

10. Holzmueller RLP Therapists I have known and (mostly) loved. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005; 59(5): 580-587. [ Links ]

11. Bazyk S. Changes in attitudes and beliefs regarding parent participation and home programs: An update. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1989; 43(11): 723-728. [ Links ]

12. Grange H. Occupational therapy is all this OT OTT? The Star. 2010 February 5; Lifestyle Section: 13. [ Links ]

13. Wikipedia: OTT. [Online]. [cited 2013, December 10]; Available from: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/over_the_top. [ Links ]

14. Roley SS, Mailloux Z, Miller-Kuhanek H, Glennon T. Understanding Ayres Sensory Integration. OT Practice. 2007; 12: 17. [ Links ]

15. John W. Creswell. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage; 2009. [ Links ]

16. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1991; 45(3): 214-222. [ Links ]

17. Parham LD, Cohn ES, Spitzer S, Koomar JA, Miller LJ, Burke JP, et al. Fidelity in sensory integration intervention research. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007; 61(2): 216. [ Links ]

18. Coster W. Occupation-centered assessment of children. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998; 52(5): 337-344. [ Links ]

19. Royeen CB, Marsh D. Promoting occupational therapy in the schools. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1988; 42(11): 713-717. [ Links ]

20. John W. Creswell. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage; 2009. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jacintha Smit

jgeralsmit@gmail.com