Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.48 no.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/23103833/2018/vol48n2a6

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

"We are the Peace Team": Exploring transformation among previously gang-involved young men in Cape Town

Lisa WegnerI; Megan Lee BrinkII, *; Maliekah JonkersIII, *; Shandre MampiesIV, *; Roxanne Lee StemmetV, *

IBSc OT (Wits), MSc OT (UCT), PhD (UCT); Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape

IIBSc OT (UWC); Occupational therapist, Private Practice

IIIBSc OT (UWC); Occupational therapist, Rita Henn and Partners based at Intercare Sub-acute and Rehabilitation Hospital

IVBSc OT (UWC); Not currently employed

VBSc OT (UWC); Occupational therapist, Stepmed Paramedical Rehabilitation Centre

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Many young men in South Africa belong to gangs which has negative consequences for individuals and society. Disengaging from a gang is difficult as it requires transformation; however, little is known about transformation in previously gang-involved youth. This study therefore aimed at exploring the experiences of transformation through occupational engagement in a group of young men who were previously involved in gangs. The objectives were to explore the young men's experiences of how occupational engagement facilitated, and sustained, their transformation to an ex-gang lifestyle, and the challenges which they faced

METHODS: In this descriptive, qualitative study, ten young men who were previously involved in gangs and subsequently became part of a group called the "Peace Team" participated in four focus groups. Data obtained were analysed thematically

FINDINGS: The first theme "There's that sense of change" depicted the participants' experiences and perceptions about their transformation out of gangs. The second theme "We are the Peace Team" showed that belonging to the Peace Team facilitated and sustained transformation as this provided opportunities to engage in non-deviant, pro-social occupations. The third theme "We will be the change" depicted the participants' perceptions that change started with themselves and then spread to others. Challenges included the social and emotional ties to the gang and threats to personal safety

CONCLUSION: The study provided insight into the transformation that takes place as young men disengage from gangs. Occupational therapists could create opportunities for supportive development through occupational engagement to assist young men to disengage from gangs and transform their lives

Key words: disengagement, gangs, occupational engagement, transformation, young men

INTRODUCTION

In South Africa, youth involvement in gangs is extremely common and problematic, particularly in the Western Cape. There are negative consequences for gang-involved youth including dropping out of school, unemployment, substance abuse, crime, juvenile conviction and imprisonment1. There are also implications for families, communities and society in general, such as increased violence, crime, vandalism, assault, drug trafficking and even homicide. Previous research has shown that for young men, gang involvement offers social support, material resources including drugs and money, independence, thrills and excitement, and serves the purpose of providing a sense of belonging and of proving manhood2. Whilst some research has been conducted in other countries, little is known in South Africa about the factors that motivate young men to leave or disengage from gangs, and the transformation process involved in this disengagement.

Disengaging from a gang is difficult due to the changes and transformation required. Change is part of human existence; as individuals strive to reach their potential for any reason, or make adaptations to their lives, change has to occur3. The change which is initiated can be regarded as a reawakening of possibilities for development, or transformation3. The process of transformation in gang members is supported by the theory of Giordano, Cernkovich and Rudolph4 who proposed that when a gang member decides to make the shift to leave the gang, it is encouraged by personal and/or environmental factors. These factors allow the person to choose to disengage as the positive outcomes far out-weigh those which were experienced whilst in the gang5. Disengagement can be seen as a process of transformation out of the gang into a new lifestyle. When individuals undergo transformation, they perceive new meaning to their lives, events, and interactions with others6.

The question that arises is how is transformation sustained? In order for transformation to occur, there needs to be supportive development which is equitable for all3. Supportive development could for example, include the support of family and friends, skills development, and engagement in occupations such as work, leisure or recreational activities. A challenge is that supportive development may be hindered by contextual factors such as a lack of infrastructure and resources, particularly in lower socio-economic communities. There may be a potential role for occupational therapists to create opportunities for supportive development through occupational engagement to assist young men to disengage from gangs and transform their lives. However, little is known about transformation in previously gang-involved youth. Therefore, the current study addressed the following question: what are the factors that facilitate and sustain transformation in young men as they disengage from gangs?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Gangs in South Africa

Gangs have a long history in the South African context, dating back to the early 20th century7. During the apartheid regime, people were relocated from central Cape Town to the Cape Flats and surrounding townships due to the Group Areas Act. One consequence was that many young men joined street gangs to fight for their territory8. Since the demise of apartheid in 1994, gangs in the Cape Flats have continued to flourish. More recently, gangs have formed in townships such as Nyanga, which is notorious for being one of the most dangerous places in South Africa9 and regarded as the country's murder capital10. In the townships, there are two rival gangs: the Vatos Locos and the Vuras11 which recruit members as young as 12 years from local schools12.

Reasons for becoming involved in gangs

Youth join gangs due to conditions in the social environment such as poverty, family problems, lack of success at school, and for reasons of safety, protection, support, excitement, financial opportunity and a sense of belonging13. Factors which place young men at risk of joining gangs include low socio-economic communities, one-parent households, parent/s involved in gangs, low academic achievement, and association with friends who engage in delinquent behaviours14. Gangs have a perceived organised structure or hierarchy which displays smaller systems with particular boundaries just as family's do15. Youth are attracted to gangs because of the perceived supportive aspects such as the feeling of security which they may lack in their own family environments as well as the connection to something greater than oneself16. Similarly, in Cape Town, South Africa, it was found that young men found in gangs the security that they sought as a result of unsupportive environments such as broken families or absent fathers2.

Disengaging from gangs

Much of the previous research with gang-involved youth was conducted in the United States of America (USA), and has shown that leaving a gang, also known as gang disengagement or desis-tance, may be a long and challenging process with many failures and obstacles17,18. Pyrooz and Decker examined the motives for leaving a gang which they termed "push and pull factors"17:420. Push factors are largely internal to gang life and make the persistence of gangs in the social environment unappealing, for example, tiring of gang violence; therefore, they are viewed as pushing the individual away from the gang17. Pull factors are largely external to the gang, for example, family or work commitments. Because these factors typically operate outside of the gang's control, they are viewed as pulling individuals away from the gang and directing them toward new activities and pathways17.

Decker, Pyrooz and Moule investigated the process of disengagement from gangs in a mixed methods study of 260 former gang members conducted in the USA18. They found that disengagement could be viewed as a series of role transitions, often taking place during the transition to adulthood18. Individuals fluctuated between the stages of being "completely in" the gang, "first doubts", "anticipatory socialisation", "turning points" and being "completely out" of the gang18:273. First doubts start in the back of the individual's mind and gradually become more prominent, for example, having doubts about the gang lifestyle18. Anticipatory socialisation entails a process of role experimentation such as joining a gang outreach programme or trying to become a better parent by severing ties with the gang. Turning points were identified as specific events or times for leaving a gang, and many of these were as a result of exposure to violence or due to family issues. Being completely out of the gang required "post-exit validation" of the new roles in order to support the member disengaging from a gang18:276. The validation of the new status came from within the individual, but also from external groups including the former gang, rival gangs, family members and the police18. Some individuals moved through the stages quickly, some moved back and forth, and others stalled in a particular stage18. Clearly, individuals have to make many changes in their lives as they disengage from gangs and transform to an ex-gang lifestyle.

Transformation from an occupational perspective

The transformation process can be explored from an occupational perspective, thus providing an alternative means of understanding gang disengagement. An occupational perspective is an examination of "what individuals do every day on their own and collectively; how people live and seek identity; how people organise their habits, routines, and choices to promote health; and how systems support (or do not support) the occupations people want, or need, to do to be healthy''19:3. Engagement in occupations provides people with a sense of meaning and purpose, but occupations can also be maladaptive and harmful for individuals and society. For example, previous research has shown that young men's engagement in gang-related occupations, such as fighting enemy gangs, provides meaning and purpose; however, it simultaneously prevents them from engaging in pro-social occupations such as playing team soccer2. When the decision is made to leave a gang, the transformational power within occupation can bring about development and maturation when the choices and processes are meaningful3.

However, very little is known about how occupation facilitates and supports transformation of youths who leave gangs in South Africa. Furthermore, previous research on gang involvement has focused more on the reasons for, and the consequences of, joining a gang, and less on gang disengagement17,18. Furthermore, studies were largely conducted in the USA in fields including juvenile jus-tice13, social development14, family studies15,16 and criminology17,18. Therefore, the review of literature revealed a need for research on the transformational experiences of previously gang-involved youth in South Africa to be conducted by occupational therapists. This research would enhance occupational therapy practice by informing the development of relevant programmes to support young men as they disengage from gangs.

METHODS

Study aim and objectives

The aim of the study was to explore the experiences of transformation through occupational engagement in a group of young men who were previously involved in gangs. The objectives were to explore the young men's experiences of how occupational engagement facilitated and sustained their transformation to an ex-gang lifestyle, and the challenges which they faced in sustaining this transformed life.

Research design

A descriptive, qualitative research design was used to conduct the study. This research design provides straightforward descriptions or summaries of experiences and events in everyday terms, and enables researchers to "stay closer to the data and to the surface of words and events"20:336.

Participant selection and recruitment

The study included ten young men from Nyanga who were ex-gang members. They subsequently joined a group called the "Peace Team". The Peace Team was established in Nyanga in 2013 with twelve members. The objectives of the Peace Team were to create social cohesion, resolve conflict amongst the youth, dissuade them from re-joining gangs, and aid youth to leave gangs21. The Peace Team implemented a programme in a high school in Nyanga with the intention of developing a gang-free, violence-free, learning environment. Staff members of the HIV and AIDS Programme at the University of the Western Cape worked with the Peace Team to develop skills such as conflict resolution to assist them with their work in Nyanga. The researchers approached the HIV and AIDS Programme director and requested a meeting with the Peace Team. Therefore, convenience sampling was used to recruit the participants as they were part of an already existing group known to the researchers. Convenience sampling has been described as one form of non-probability or non-random sampling in which members of the target population are selected for the purpose of the study if they meet certain practical criteria, such as geographical proximity, availability at a certain time, easy accessibility, or the willingness to volunteer22.

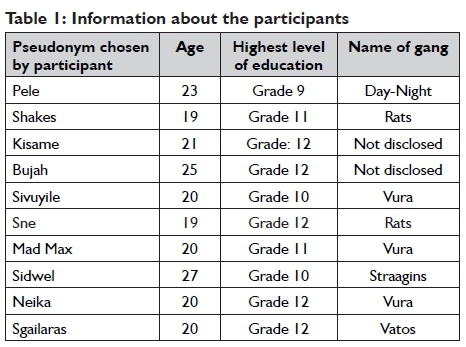

The researchers met with the original twelve members of the Peace Team to initiate a relationship and introduce the research topic. The second meeting was held at the university to agree on the rules of engagement between the researchers and the Peace Team and further develop the relationship. A psychologist from the HIV and AIDS Programme at the University of the Western Cape mediated rules of engagement and the expectations of the research relationship. The researchers presented the proposed research topic, aim, objectives and the procedure of the research to the participants. This was discussed in depth by the researchers and the participants until final agreement on the topic of research was reached. The researchers agreed to offer a workshop with the Peace Team to equip them with introductory group facilitation skills to assist them in facilitating their own groups in schools. Through these meetings the researchers built trust with the Peace Team which was important for the research process due to the sensitive nature of the topic. At the next meeting, ten members of the Peace Team attended and gave their consent to participate voluntarily in the study (Table 1 below).

Data collection procedure

Focus groups are described as controlled discussions with a selected group of individuals to gain information about their views and experiences of a specific topic23. The advantages of focus group research includes gaining insights into people's shared understanding of everyday life and the ways in which individuals are influenced by others in a group situation23. For these reasons, data collection for the current study was done through four focus

groups. The dates, times and meeting places of the focus groups were decided and agreed upon together with the participants. Participants were divided randomly into two groups of five participants each to ensure that all members had equal opportunity to participate in the focus group discussion. Two focus groups were conducted with each group ten days apart and the same two researchers ran each group respectively, whilst the other researchers observed and made field notes. The first two group sessions took place on the same day and at the same time at the high school with all ten participants present. The second two group sessions took place on the same day and at the same time at the university with nine participants present. One participant was absent as he had been injured.

Semi-structured question-guides relating to the objectives of the study were used to guide the focus group discussions (Table II below). Semi-structured question-guides provide the questions and topics that must be covered during the group although the researcher decides the order in which questions are asked and uses probes to obtain richer information24. This enables the researcher to collect detailed information and understand answers thoroughly in a conversational way24. The four focus groups allowed the researchers to engage in an iterative process of analysing the participants' responses from the first groups, and then developing further questions for discussion in the next groups.

Data analysis

The focus groups were audiotaped using digital recorders and then transcribed verbatim by the researchers. Thematic analysis was used to identify codes, categories and themes through an inductive approach, which has been defined as being "data-driven" in that the coding of data occurs "without trying to fit it into a pre-existing coding frame, or the researcher's analytic preconceptions"25:84. Each researcher read the transcripts a few times, and developed codes with supporting quotes from the data. Thereafter, the researchers discussed the codes to reach consensus and then grouped the codes into categories. Through further discussion the researchers identified similarities in categories and grouped these to create themes which were named using in-vivo quotes from the data. A thematic map25 of the analysis was developed (Table III on page 37), and the themes were further defined to tell a story relating back to the research question and study objectives. Finally, the themes were interpreted in terms of related literature.

Trustworthiness

It is important that qualitative research is deemed to be trustworthy or rigorous, and that strategies are used to ensure credibility, transferability, confirmability and dependability26. Several strategies were employed to ensure trustworthiness. The study was conducted by multiple researchers (five) with multiple participants (ten) ensuring triangulation of investigators and data sources, respectively. The researchers discussed the analysis and developed a combined representation of the findings. Multiple participants meant that varying responses and viewpoints could be obtained during the focus groups and provided a rich description of the participants' experiences. In addition, member checking was conducted to verify the findings with the participants; on completion of data analysis, a follow up group session was arranged with the participants to discuss and clarify if they agreed with the researchers' interpretation of the findings.

Ethics

The study received ethics clearance from the Senate Research committee at the University of the Western Cape (ethics clearance number 14/6/16). Participants took part voluntarily in the study and gave informed, written consent. Their identities were kept confidential through the use of self-selected pseudonyms. A psychologist at the university was available for participants during the study if they required support; however, none of the participants made use of this service.

FINDINGS

Three themes emerged from the analysis of data and were named using participants' quotes: "There's that sense of change"; "We are the Peace Team"; and "We will be the change". The themes with their related categories and codes are presented in Table III.

Theme 1: "There's that sense of change"

The theme "There's that sense of change" depicted the participants' experiences and perceptions about their transformation out of gangs. The participants perceived transformation as changes that took place in their lives, as evidenced by Pele in the name of this theme.

So, some of the guys are playing street soccer, you see, some of the guys are DJ's now, you know what I'm saying? So there's that sense of change. (Pele)

Events triggering leaving gangs

The participants spoke of the events that triggered their disengagement from the gangs, and shared their stories of being confronted with shocking experiences that included witnessing their friends being killed or feeling that they might be killed.

Shit gets real here, [I'm] gonna [going to] die. (Mad Max)

Reflecting on these shocking experiences made them realise that there were negative consequences to belonging to a gang, which resulted in a desire to leave the gang and change their lives.

We like, it's like we neglected ourselves from the larger community because we couldn't do what other people are doing because we are wanted [by the police] you see, so I said to myself "this is not life". (Pele)

I was wanting to experience another life, a free life, a normal life [the same] as everyone else. (Sidwel)

"Have direction"

The participants had to find direction in their lives by changing their outlook. This required participants to redirect their attitudes towards life and think about new pro-social roles.

Have direction, like most of our friends now are working, are starting to look for work, others are working, others are still at school, others are in colleges now. (Sne)

Finding direction required participants to believe in themselves in order to achieve their goals.

You can do anything you set your mind to, sky is not the limit, you can go over that. Free mind, anything is possible, dream big you know and if you dream big, you will achieve big. (Kisame)

Changing lifestyle

Changing their lifestyles meant that the participants had to avoid previous occupations and engage in different occupations.

I don't go to parties, I don't drink, every time I'm at my home watching TV busy with my WhatsApp or with my girlfriend. (Sidwel)

The participants spoke about how they could reflect on their gang involvement after leaving the gang and this gave rise to positive feelings such as feeling free.

When you outa [out of] that situation, you can actually look at it objectively, you know you can actually see it clearly like okay, this is what was happening you know, it's a sense of freedom. (Kisame)

Proving through actions

One of the consequences of previous gang involvement was that the participants had to prove to their families, friends and the community through their actions that they had changed.

An individual must be transparent and must prove that he's changing by his actions. In order for an individual to be out [of] a gang he must prove it by his actions. The way he dress[es], the way he talks, the people he hangs out with - those actions, they make the community and the gangs in the community see that by his actions he wants to change and he's changing. (Pele)

Support

The participants agreed that without the support of their families, their transformation would not have been possible.

She [mother] gives me, she always motivates me but [I'm] not saying she has the money, she is making a lota [lot of] sacrifices. (Sne)

Can't survive without them [family]. (Sne)

Challenges with leaving the gang

The participants acknowledged that leaving the gang and transforming their lives came with many challenges.

it's gonna [going to] be a hard road. We not gonna fool ourselves and say it's gonna be [an] easy journey, you know, it's gonna be a hard road. (Kisame)

The process of transformation did not occur in isolation as many other elements were involved, in particular the gang itself. The participants spoke about the pressure put on them by their friends to stay in the gang.

I had a conference with my own friends, because they didn't want me to get outa the gang you see. They force me to stay in the gang because they knew that when I'm in the gang I'm a leader. (Pele)

Leaving the gang meant leaving behind friends, who could potentially become enemies.

They [the gang members] started forcing us to fight, then we decided to fight back against them. So now it's kinda hard because now my own friends are my own enemies. But luckily enough the guys that I was fighting with have been lenient with me because I grew up with them so they said okay its fine if you wanna stop fighting we won't hurt you or do anything. (Sne)

Participants had to face the temptations of gang involvement such as easy access to money.

Because I can change, but if I'm still broke I'll go back to crime. (Pele)

The participants had to find ways to protect themselves and adapted their routines as part of sustaining the change to a new lifestyle.

Even if you have to wear your bag to school and even wear those big sun glasses, your nerd sun glasses, you see or when we go to the gym, you even go to the gym running. (Pele)

Trying to survive every day, you have to know at certain places which people should see you, because phones here are very dangerous. (Sne)

Theme 2: "We are the Peace Team"

The second theme "We are the Peace Team" highlighted the fundamental role of the Peace Team in facilitating the process of transformation and sustaining the participants' new lifestyles.

"We are the peace makers"

After leaving the gang, the participants saw themselves as peace makers and protectors in their community. To the participants, making peace in the community meant making a difference and having a positive impact on the youth of Nyanga.

To me a peace maker means to make love with people, to make peace in the community and a peace maker likes to protect us in our environment. I can say that. (Sgailarus)

Engaging in pro-social roles and occupations

The participants reflected at length about what it meant to be part of the Peace Team. The Peace Team was more than just the name of the organisation to which the participants belonged. Being part of the Peace Team provided the participants with opportunities to engage in pro-social roles and occupations that focused on peacemaking in Nyanga. One main role of the Peace Team was keeping track of gang-related activities that occurred in the community, which one participant referred to as:

Like we are an ear of the community. (Pele)

The Peace Team enabled the participants to be peace makers in the community, have a voice against gangsterism and explore their talents.

The Peace Team, like, it has facilitated that now we are the voice of anti- gangsterism in Nyanga East, we are the voice of peace, see we are the voice of the youth because we might be all gangsters and we think we have a certain goal and that is to kill, but that's not all, ... some of us have talents, some of us have different things, like to expand our talents and all that stuff to go through life and achieve stuff. (Sne)

Being part of the Peace Team allowed the participants to learn how to be peaceful mediators in their community and find peaceful ways to handle conflict, as opposed to the violent methods they had used previously in gangs.

The Peace Team has shown me how to be a man by talking, to not being a man by a gun. I can stand with everyone and talk, but with respect and dignity, not by fighting and doing all those sort of those things. [Pause] And it taught me to stand on my two feet and know when to say no and know when to say yes and how to say yes and where to draw the line. (Sidwel)

The participants felt hope for their futures as part of the Peace Team.

I think the Peace Team it gives me hope that there is a better way, there is a better future, we can actually do something. (Pele)

All of the participants agreed that being part of the Peace Team was a positive factor in enabling them to transform their lives.

It [Peace Team] means motivation, support, and confidence." (Sne)

I had to look for something else better to do, so this is why I think joining the Peace Team is making a difference in my life because [there is] no crime or violence that is happening that I'm involved in anymore so I feel kinda relaxed now. (Sne)

As part of the Peace Team, participants felt that they were role models to one another as well as others in the community.

Peace Team has showed us the correct way because there's not many male role models in our lives, and the Peace Team has mostly male youth, they have inspired us now to be the ones whom the younger ones look up to and who our peers look up to. (Sne)

Peace Team - we [are] role models to other people in our community. (Shakes Mapara)

The Peace Team worked most days in a local high school in Nyanga on an informal basis, giving presentations about gangsterism, raising awareness of the challenges and engaging in conflict resolution with the learners. This gave them a sense of pride.

And now when we go to these schools and do presentations about gangsterism and [raise] awareness, we feel like we can be the change because when you look at five hundred students listening to you, telling them that [gangs] is not right, you feel proud of yourself (Sne)

Challenges with new role

Despite working at the school, the participants expressed difficulty having a schedule.

It's difficult to spend our everyday daily life in a way that we [are] not gangsters anymore, it's hard to have a schedule. (Shakes Mapara)

They also admitted to still using substances such as cannabis.

Most of us still smoke, we still walk around at night, sometimes we not peaceful like we [are] not angels. (Sne)

"Brotherhood"

The Peace Team believed that they were a 'brotherhood' and that they were protected by being in the Peace Team. This was important as they perceived Nyanga as being a hard place to live.

Nyanga East can be a place to live in, a place where you won't have to look over our shoulders anymore, because I know the one who is behind me, he has the mentality that he's my brother, we are in for peace now. (Sne)

But the thing is we are looking for [after] each other's back, that's the main thing. No matter how hard it is in Nyanga and no matter how people fight or police are beating people, we stand together. (Sidwel)

"We will be the change"

The theme "We will be the change" depicted the participants' perceptions that change started with themselves and then spread to others.

"I must spread the change"

Being members of the Peace Team and peace makers enabled the participants to make positive changes in their community that focused on creating social cohesion and resolving conflict amongst the youth of Nyanga.

I'm making a change and you become more ambitious now, like starting to live positively because you know if I want change, I must be the change first, and then now the people see changes, I must spread the change. (Sne)

The Peace Team strongly believed that they were the first generation to bring about change and that this would inspire generations that follow.

So now for us it will be the first generation - we will be the change. (Sne)

The participants expressed how by working with youth, changes could take place and life would be improved.

If more young people can do what we are doing, the world will be a better place. (Pele)

Changing perceptions

The participants felt that as they changed, people's perceptions about themselves and about Nyanga, would also change.

Because part of this is for us to change, and change how the people look at Nyanga East and how people look at South Africa, and most of all change the way our parents look at us. (Sne)

DISCUSSION

The study provided an understanding of the factors that facilitated, and sustained, transformation in young men as they disengaged from gangs in Nyanga. Importantly, the study contributed a new perspective by highlighting how occupational engagement played a role in the transformation process.

The study findings revealed that, for the participants, disengagement from gangs occurred in a series of stages over time. This finding is supported by previous studies by Pyrooz and Decker17 and Decker, Pyrooz and Moule18 who reported that gang disengagement took place through a series of role transitions. The first theme "There's that sense of change" highlighted the participants' experiences of having "first doubts"18 where they realised the negative consequences of being in a gang and contemplated life out of a gang. All of the participants experienced specific events or "turning points"18 including violent and sometimes life threatening incidents that provoked their decisions to leave the gangs. Previous studies supported the finding that violent incidents were a motive for pushing individuals out of a gang17,18. 'Anticipatory socialisation" involved severing ties to old roles18:274 and was observed when participants spoke about talking to their gang members about leaving the gang.

A major contributing factor to sustaining transformation was the participants' roles as peace makers by being part of the Peace Team, which was highlighted in theme two "We are the Peace Team". The Peace Team provided the participants with opportunities to engage in non-deviant, pro-social occupations and try out new roles, which was regarded as "anticipatory socialisation"l8. In addition, being in the Peace Team provided the participants with routine and it structured their use of time, as they participated in what they termed their "gang prevention programme" with youth at a local high school on a daily basis. This programme could be regarded as voluntary work, and provided many positive opportunities for the participants to demonstrate to their families and the community that they had transformed to a gang-free, pro-social lifestyle. It was beyond the scope of the current study to determine the nature and efficacy of the gang prevention programme that was offered by the Peace Team, but this could be addressed in future research.

In the third theme "We will be the change", participants spoke about feeling that they were changing the youth of Nyanga whilst changing themselves. When leaving the gangs, the participants were faced with various choices about which directions they could take which would allow them to transform. By having direction and redirecting their goals in life, the participants chose new occupations which facilitated transformation. This is a process of pro-social reintegration into community life, and was largely facilitated and sustained through their participation in the Peace Team. By engaging in meaningful, positive occupations such as peace keeping and their work in the school, the participants experienced a sense of constructive purpose in their occupational engagement. In this way, participants proved to themselves and others that they could change and transform to be completely out of the gang. This provides evidence of the final stage of disengagement from gangs known as "post-exit validation"18. Validation of an individual's status as a former gang member and moving into a new role requires both internal (from self), and external, validation (from others)18. The participants acknowledged that their families played a crucial role in supporting them financially and emotionally which helped them through the transformation process. Previous research has shown that family support is imperative in assisting disengagement from gangs27. However, proving to others - including family and the community - that they had changed was an ongoing challenge for the participants.

Sustaining transformation comes with many challenges. The participants explained how it was a struggle to refrain from returning to a gang lifestyle. One challenge was feeling pressured by gang members to return to the gangs, and having friends who were still in gangs. The social and emotional attachments to the former gang that persist despite having left the gang are known as "gang ties"17:420. Previous research has shown that in communities where the presence of gangs and gang activity is high, it is possible to leave one's gang and retain ties to the gang17. Another challenge was the threat to their personal safety as the participants felt threatened by other gangs in Nyanga. The lure of easy money and access to drugs also posed challenges to the participants.

Limitations

The main limitation was the language barrier between the participants and the researchers. All of the participants were first language Xhosa speakers and none of the researchers could speak Xhosa fluently. Some participants had difficulty understanding the English questions; therefore, the researchers had to adapt and simplify the manner in which the questions were posed or ask other group members to translate. As a result however, participants sometimes provided brief responses to questions.

IMPLICATIONS FOR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

The study provided insight into the transformational power of occupation and occupational engagement in the context of gang disengagement. Occupational therapists could consider their role in harnessing the power of occupational engagement to support young men's disengagement from gangs. This could be done by creating opportunities for supportive development through community-based interventions that facilitate young men's participation in pro-social, constructive occupations, roles and activities. The interventions could include skills development, for example, parenting skills, life skills and vocational training. Occupational therapists could develop interventions focusing on promoting work and leisure engagement in partnership with non-governmental and community-based organisations such as high schools and community recreation centres, as well as government departments including Community Safety and Social Development.

CONCLUSION

This study explored the transformation experiences of young men who were previously involved in gangs. A main finding was that their participation in the Peace Team enabled them to be peace makers in the community and role models to other youth. As such, the Peace Team believed that they were a positive influence in the community of Nyanga and this assisted with sustaining their transformation. The study highlighted the importance and relevance of pro-social occupational engagement in the process of transformation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the courage of the young men of the Peace Team and thank them for participating in the study and sharing their stories with us.

REFERENCES

1. Cooper A, Ward CL. Intervening with youth in gangs. In: Ward C, van der Merwe A, Dawes A, editors. Youth violence: Sources and solutions in South Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press; 2012: 258-272. [ Links ]

2. Wegner L, Behardien A, Loubser C, Ryklief W, Smith D. Meaning and purpose in the occupations of gang-involved young men in Cape Town. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46(1): 54-59. [ Links ]

3. Watson R. A population approach to transformation. In: Watson R Swartz L, editors. Transformation through occupation. London: Whurr Publishers: 2004: 51-64. [ Links ]

4. Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA, Rudolph JL. Gender, crime, and desistance: Toward a theory of cognitive transformation. American Journal of Sociology. 2002; 107(4): 990-1064. [ Links ]

5. Goodwill AO. In and out of Aboriginal gang life: Perspectives of Aboriginal ex-gang members [unpublished dissertation]. University of British Columbia; 2009. [cited 2014 June 6]. Available from https://circle.ubc.ca/bitstream/handle/2429/ll076/ubc_2009_fall_good-will_alanaise.pdf?sequence=1. [ Links ]

6. Daszko M, Scheinberg S. Survival is optional: Only leaders with new knowledge can lead the transformation. c2005 [cited 2014 Jul 22]. Available from http://www.mdaszko.com/theoryoftransforma-tion_final_to_short_article_apr05.pdf [ Links ]

7. Steinberg J. The Number: One man's search for identity in the Cape underworld and prison gangs. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers; 2004. [ Links ]

8. Wideangle. South Africa: Gangs of the Cape Flats. c2006. [cited 2015 Aug 18]. Available from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/wideangle/episodes/18-with-a-bullet/gangs-and-youth-violence-around-the-world/africa/1539. [ Links ]

9. Crime Statistics. It's not safe here. City Press [newspaper online]. 2012 Sept 12 [cited 2014 March 3]. Available from http://www.citypress.co.za [ Links ]

10. Nombembe P Nyanga the murder capital. Sunday Times Live [newspaper online]. 2013 Sept 20. [cited 2014 March 3]. Available from www.timeslive.co.za/thetimes/2013/09/20/nyanga-the-murder-capital [ Links ]

11. Roloffis N. Gangs a mirror of society's shortcomings. Iolnews [newspaper online]. 2014 March 10 [cited 2015 Aug 16]. Available from http://www.iol.co.za/news/gangs-a-mirror-of-society's-shortcomings-1.1655565. [ Links ]

12. Khayelitsha Gangsters. News24 [newspaper online]. 2012 Jul 5 [cited 2014 Sept 12]. Available from http://www.news24.com/MyNews24/Khayelitsha-Gangsters-20120704. [ Links ]

13. Young M, Gonzalez V Getting out of gangs, staying out of gangs: Gang intervention and desistence strategies. National Gang Centre Bulletin. 2013; 8: 1-10. [ Links ]

14. Hill KG, Lui C, Hawkins JD. Early precursors of gang membership: A study of Seattle youth. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. 2001 [cited 2017 Aug 1]. Available from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/ojjdp/190106.pdf. [ Links ]

15. Ruble NM, Turner WL. A systemic analysis of the dynamics and organization of urban street gangs. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2000; 28: 117-132. [ Links ]

16. McNeil SN, Herschberger JK, Nedela MN. Low-income families with potential adolescent gang involvement: A structural community family therapy integration model. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2013; 41: 110-120. [ Links ]

17. Pyrooz DC, Decker SH. Motives and methods for leaving the gang: Understanding the process of gang desistance. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2011; 39: 417-425. [ Links ]

18. Decker SH, Pyrooz DC, Moule RK. Disengagement from gangs as role transition. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014; 24(2): 268-283. [ Links ]

19. Whiteford G, Townsend E. Participatory occupational justice framework: Enabling occupational participation and inclusion. In: Kronenberg F, Pollard N, Sakellariou D, editors. Occupational therapy without borders: Learning from the spirit of survivors. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2011: 65-84. [ Links ]

20. Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000; 23:334-340. [ Links ]

21. Vulisango Youth for Peace. c2013 [cited 2016 Mar 21]. Available from https://vulisango.wordpress.com/about/. [ Links ]

22. Dörnyei Z. Research methods in applied linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007: 93-123. [ Links ]

23. Gibbs A. Focus groups. Social Research Update, Issue 19. 1997. [cited 2016 May 11]. Available from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic549650.files/Focus_Groups.pdf. [ Links ]

24. Harrell MC, Bradley MA. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. 2009. [cited 2014 Jul 23]. Available from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2009/RAND_TR718.pdf. [ Links ]

25. Braun V Clarke V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3: 77-101. [ Links ]

26. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991; 45(3): 214-222. [ Links ]

27. Van Ngo H. Unraveling identities and belonging: Criminal gang involvement of youth from immigrant families. Calgary, AB: Centre for Newcomers. 2010. [cited 2016 Mar 21]. Available from http://www.threesource.ca/documnts/June2011/unravelling_identities.pdf. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lisa Wegner

lwegner@uwc.ac.za

* Undergraduate students registered in the Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, at the time of the study