Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.48 no.1 Pretoria Abr. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol48n1a6

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Women's experiences of informal street trading and well-being in Cape Town, South Africa

Sharyn SassenI; Roshan GalvaanII; Madeleine DuncanIII

IBSc (OT) UCT, MSc (OT) UCT. Clinical Educator: Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences UCT

IIBSc (OT) UCT, MSc (OT) UCT, PhD (OT) UCT. Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town

IIID Phil (Psych) US, MSc (OT) UCT. Associate Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Street trading is one of the largest sub-categories in South Africa's booming informal economy.

RESEARCH PROBLEM: The scarcity of occupational science/therapy literature around informal economy occupations limits the profession from understanding their implications for well-being and development.

RESEARCH PURPOSE: Contextually relevant conceptions of survivalist occupations such as street trade will inform occupational therapy practice for social change and development.

RESEARCH AIM AND OBJECTIVES: The study aimed to describe women street traders' experiences of street trading and well-being. The objectives were to identify the positive and negative well-being outcomes of engagement in street trading and to identify the social, economic and political factors that influence the well-being of women street traders.

RESEARCH DESIGN: An ethnographic inquiry was carried out with four women survivalist street traders identified through purposive sampling.

RESEARCH METHODS: Participant observation and in-depth one-on-one ethnographic and photo elicitation interviews were carried out with each participant.

DATA ANALYSIS: Audio recordings were transcribed for inductive and thematic cross case analysis.

FINDINGS: The qualitative essence of street traders' experiences of navigating a livelihood in the fluid and unstable context of the informal economy was captured in one theme, 'Togetherness: steering against the current towards a better life'. The theme comprised three categories: 'Taking the helm', 'Facing tough conditions' and 'We're in the same boat'.

DISCUSSION: Street trading is a valued means for taking action towards economic survival and well-being. The contextually situated nature of this occupation translated to both adverse and advantageous experiences, resulting in a nuanced sense of well-being as thriving while surviving.

CONCLUSION: Women's well-being as street traders is primarily determined by the quality of their collective camaraderie, social connectedness and personal drive.

Key words: Street trading, informal economy occupations, well-being, occupational injustice, social connectedness

INTRODUCTION

South Africa's formal work sector faces a 26.5% national unemployment rate and an under-recognition of the contribution that work in the informal sector makes to the country's gross domestic product (GDP)1. Informal work refers to a form of productivity where workers are self-employed, or work for those who are self-employed. Informal work is characterised by insecure employment and little to no labour protection because it is under-regulated by governmental systems2,3. Informal workers engage in a wide range of economic activities such as street vending, refuse collecting and scrap-material recycling. In the final quarter of 2012, there were 2.1 million people in South Africa active in the informal economy (excluding the agricultural sector)4. Of the 2.1 million, 1.2 million were men and just over 857 000 were women4. By its very nature, informal economic activity goes unrecorded and is therefore difficult to measure, but some estimates value the informal economy at around 28% of South Africa's GDP1.

Informal trade, commonly referred to as street trade, is one of the largest sub-categories of informal work in South Africa5. It involves selling any goods or supplying any service for reward in a public space. Street trade emerges as an agentic response to economic opportunity, a preference for independence, and a creative option beyond low-waged formal employment5. Street traders are predominantly black women, driven into the informal economy by desperation for work. They engage in survivalist forms of street trade such as selling sweets, chips or vegetables and are at risk of being further displaced into marginal income-generating options as competition grows in the informal economy. Household and reproductive responsibilities combined with poverty drive women into flexible, low risk economic activity. Street trade occurs in unprotected and unsecured places thereby restricting street traders' income generation and increasing their vulnerability to injury, illness and chronic diseases6,7. Street traders tend to have limited access to affordable and appropriate health care for themselves and their families and may not seek care, especially when they have an insecure legal status, or are concerned with the potential expense or loss of income associated with seeking care. It is important for occupational therapists to generate knowledge about informal work given the critical role that it plays in the economic survival and health of marginalised people who access public sector occupational therapy services in South Africa.

This article presents the findings of the first author's ethnographic inquiry exploring women's experiences of survivalist, street trading in the Cape Town Central Business District (CBD), identifying how this form of self-employment contributes to their well-being.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY CONCEPTIONS OF WELL-BEING AND WORK

A literature review by Aldrich8 on well-being found that it is associated with continued being, becoming, belonging and meaningful doing. Descriptions of well-being include contentment, life satisfaction, health, good quality of life, social support, coherence and integration8. Well-being is influenced by opportunity and choice to engage in meaningful occupations that meet an individual's needs, aspirations and development potential8. For work to be a form of occupational engagement that enhances well-being, it has to respect human rights and promote occupational justice. However, it is acknowledged that work does not necessarily contribute positively towards well-being9-11. Occupational injustice exists when people have restricted access to the necessary opportunities and resources for sustaining their livelihoods. Constructs of occupational injustice enable therapists to perceive, describe and where possible, address the structural conditions that adversely impact human well-being12. For example, people experience occupational marginalisation and alienation when they are excluded from work due to structural inequities such as disparities in power and wealth, discrimination, low wages and exposure to environmental hazards. Occupational deprivation and imbalance may occur when people are over, under or unemployed, since the positive subjective value of meaningful work is compromised. Barriers to successful engagement in street trade may include that people have limited skill sets, but also have to confront daily physical constraints, high competition, a lack of financial resources to cover location costs, an inadequate infrastructure for business efficiency, crime and poor political support. Criminalisation of street trading in some contexts has led to municipal regulations that render street traders powerless5,13. For women, in particular, social structures create the burden of multiple roles, limiting their employability in formal markets and placing them at particular risk of occupational injustice, impinged occupational rights and compromised well-being.

THE OCCUPATION OF STREET TRADING

A transactional approach to street trading as an occupation suggests that structural (physical, social, political and economic) conditions interact to shape street traders' occupational lives. Occupation, in the transactional approach, is seen as the means through which bidirectional human-context transactions occur so that people are able to function and participate in complex systems14. A transactional perspective on human doing reveals how occupation produces and reproduces relationships in the environments in which people live, work, learn and socialise15. The dynamics and outcomes of participation in occupations are key to understanding development and well-being.

The occupation of street trading is a complex transactional phenomenon comprising three central tenets: habits, context and creativity16. The structural conditions of the contexts, including power and politics, within which street traders operate influence the formation of their dispositions to act. Dewey16 refers to these dispositions as habits. He proposes that habits are shaped through contexts that influence what people do every day and how they are able (or not) to perform activities such as those associated with street trading. Habits such as the regular ways of setting up and stocking a stall, negotiating a sale and managing trade logistics are creatively adjusted to foster harmonious (or not) transactions with context. For example, the physical location of a stall, season, duration of trading time, type of products traded, type and volume of customers, gender and citizenship of the trader, competition for sales and prevailing statutory trade requirements all influence the nature of occupational engagement. More simply put, the occupation of street trading is a way in which the individual trader exists within emerging trade situations as well as creative and adaptive responses to self-employment opportunities. Thus, when the outcomes of the occupation of street trading do not foster women's functional coordination within their contexts, there are repercussions for their well-being and development17.

Amartya Sen's Capabilities Approach (CA)18 provides further understanding of the 'doing' and 'being' dimensions of street trading that may influence well-being and development. Sen's19 conceptualisation of human development as the freedom to live a good life, gave rise to the CA, a framework for evaluating well-being20 and for discerning what people are free to do and what they actually do21. Sen describes well-being as having the "effective opportunities to undertake the actions and activities that they (people) want to engage in, and be who they want to be"20. In the CA, 'function-ings' refers to the realised things people can do while 'capabilities' refer to the effectively possible things people can do20. Functionings involve basic 'beings and doings' such as being adequately nourished, as well as more complex personal aspects such as community participation or a positive sense of self21. Drawing from the CA19and Wilcock's ideas about human occupation22, it is inferred that what individuals do and are potentially able to do, who they are and are potentially able to be and what they have the opportunity to become will influence their state of well-being. Therefore, CA provides a lens to assist in understanding whether women's street trading (viewed as their functional coordination with arising situations) enables experiences of well-being or ill-being.

RESEARCH CONTEXT

Street traders in the Cape Town central business district (CBD) work facing political, socio-economic and structural restrictions that hinder their ability to grow their businesses, support their families and exert choice and control over their lives5,6. They are socially excluded through discrimination, often experiencing criminalisa-tion of their work and mistreatment by law enforcement officials. Political barriers include lack of government contribution to their street trading endeavours, no security of tenure, restrictive legislation, limited government communication and lack of participation in decision-making affecting street trade2,3. Socio-economic barriers include poor growth in the informal sector, high levels of competition with both larger, formal businesses and with other traders selling similar goods in a saturated informal market, as well as limited access to business finance5. Permits are expensive and not readily available due to a limited number of trading bays in the central city. Trading without a permit leads to confiscation or damage to limited stock, or a fine which can curtail a trader's business activities or even destroy them altogether. Some traders are unable to sell goods that are in market demand because their permits are restricted to for example selling textiles when they would make money from selling cosmetic products. Some traders sell goods not stipulated on their permits anyway, risking the legal consequences, in order to make the money needed to survive. Traders have little say in what, where and when they trade and tend to have poor knowledge of the by-laws and their rights5. For example, the City of Cape Town relocated street traders from various sites to the then newly revamped central station deck in 2010 without consulting them regarding the layout, design and allocation of the stalls. Business drastically declined for many street traders because stalls were positioned on the outskirts of the foot traffic towards the taxi rank. The stalls are ill-suited to Cape Town's weather conditions, with winter rains blowing directly into some containers, drenching traders and ruining their stock. In summer, the station deck offers minimal shade with a harsh glare reflecting off the numerous white containers and stark concrete. These conditions make street trade a precarious form of work.

STUDY DESIGN

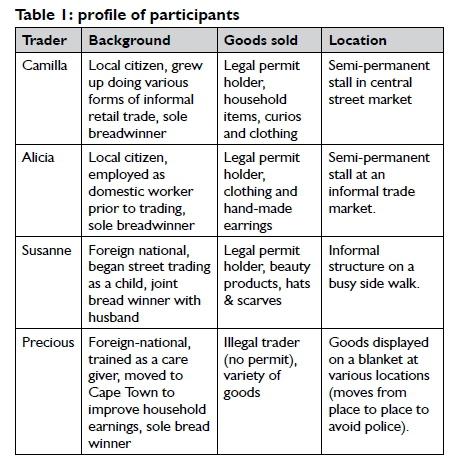

An ethnographic methodology was applied by the first author to investigate women's occupational engagement in street trade in the Cape Town central business district (CBD)23. At the time of the study 381 women were working in the informal sector in the Cape Town CBD24. Participants were accessed through CBD municipal officials and street-trade gatekeepers. Purposeful and snowball sampling was used to identify four female street traders who met the following inclusion criteria: 18 years or older, self-employed, able to communicate in English and worked as a street trader for at least one year to ensure sufficient enculturation in the field25. Sample diversity was achieved by considering the following factors across participants: variety of goods sold, type of street trade permit (city/municipality, private, un-permitted), legal registration (or not) of worker status, affiliation (membership of a trade organisation), trade location (curbside, permanent, semi-permanent market stall), citizenship (national, foreign) and social background (divorced, married, single; sole or shared breadwinner). Table 1 provides a profile of the participants (pseudonyms are used to maintain confidentiality).

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town. Data were gathered through participant observation and field notes, an initial semi-structured interview to obtain personal and occupational background information, three in-depth photo elicitation interviews about experiences of street trading and how these relate to well-being and a concluding member check interview to confirm findings. Initial grand-tour questions familiarised the researcher with women street traders' experiences of their occupation. After the initial interviews a time was made with each participant to prepare them for taking pictures and to describe the role of the photos in the research project. Each participant was instructed to take photographs that demonstrated the people, objects, events and situations comprising her experience of the street trading occupation and how these experiences impact her well-being. Participants were provided and trained in the use of disposable cameras to photograph goods, activities, people and events involved with street trade to illustrate particular experiences. The photographs were printed out and used as triggers to formulate photo elicitation interview questions pertaining to well-being. Direct, probing and interpreting questions were used in later interviews to gain information through the use of photo-elicitation methods26. All interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder and transcribed verbatim.

Field observations focused on specific aspects of activities of street trading and participants' responses and actions to events and situations within their occupation. An online data analysis application, Dedoose (www.dedoose.com), was used during initial data analysis to create coded excerpts capturing units of meaning until sub-categories were formed. Thematic analysis was then carried out inductively to yield categories and themes. The credibility and confirmability of the findings were safeguarded by longitudinal immersion in the data, member checking, reflexivity and theory triangulation. Participants were informed about the purpose, procedures, risks and benefits of the study to ensure that their autonomy was upheld. This autonomy became part of a continuous discussion to iteratively test the privacy boundaries of certain information in order to avoid exploiting confidentiality agreements. Ethical management of sensitive information was maintained by creating space for participants to express their emotions comfortably when recounting difficult circumstances around their struggle for economic survival.

FINDINGS

The qualitative essence of street traders' experiences of navigating a livelihood in the fluid and unstable context of the informal economy with other women was captured in the theme, Togetherness: steering against the current towards a better life. This theme comprised three categories: Taking the helm, Facing tough conditions and We're in the same boat. The findings respond to the research question by showing that the women's experiences and well-being as street traders are primarily determined by the quality of their collective camaraderie and personal drive.

Taking the Helm

Despite limited control over their circumstances, the women reported self-determination towards achieving positive outcomes through their work. Susanne states

Don't make like I did get the choice and then I do this [street trading]. I didn't get the choice, I do it because there was not [sic] way and I said let me find this way...

The women took the helm of ownership and control of their lives as street traders in three ways. Firstly, their responses to emergent street trading opportunities were motivated by economic, personal and family aspirations. Camilla shares how personal factors such as family legacy shaped her aspiration to provide for her family through her work.

Even at 54 I can't sit still and wait on people to give me this and give me that. Because my mom left me a legacy...we can do things with our hands. So...to, to put bread on the table (pause) we don't need to (pause), so it's in me!

Secondly, the women recounted seeking out, recognising and using opportunities for survival, economic gain and personal development provided by street trading. Precious reported:

I would start business but because of the economic situation in Zimbabwe it didn't work very well so I decided to come here, come and find a job in South Africa, Cape Town (Precious)

Thirdly, the data revealed various benefits that the women street traders gained such as a positive self-identify, money, skills development, freedom and creative expression. Camilla reported benefitting from the freedom of self-employment:

Ok sometimes you make a nice sale and you say Ok now I had it for the day' and you pack up and go...it's entirely up to you

Alicia reported that her creativity found an outlet in street trading:

I just watch Generations [a local soap opera], ok...they wearing - maybe let's say Karabo [character]- they wearing this style of earrings. You have to watch those things Generations and then you have to buy beads.

The women showed agency to meet their basic survival needs but also a desire to thrive. However, as the women aimed towards valued lives through their work, the tough conditions they persisted against had a significant impact on the financial and personal outcomes of street trading.

Facing Tough Conditions

The second category described the personal and external challenges such as limited resources and structural restrictions that the women had to deal with in constructing their working lives. Susanne described how her poor education led her to informal work:

And the problem - especially me - maybe I can't get the job before...I can't say I can do this or that one because I didn't learn for those things..

The women reported making costly personal trade-offs that detracted from their well-being. Camilla described the trade-offs between her family and street trading:

It does, it help [sic] me to support my family but on the other side I'm neglecting my family because I'm...I have to work every day.

Susanne described the difficult decision to abandon her goods and her baby in order to escape law enforcement and avoid being fined or having her goods confiscated.

Sometimes when there was-uh, when the law enforcement was coming and then I was have the stuff I was like, Ί need to run with my stuff I need to take care of my baby'. Sometimes it was difficult, sometimes I say uh-uh its better for them to take it and then I've got her. Sometimes I say no it's the police, they can't do nothing to my baby, if they see my baby they gonna take care.let me go and hide my stuff and come back.

The women had to face social, economic, political and physical restrictions while they were trying to live better lives. The social restrictions faced included being ill-treated by the law enforcement officials.

They are very rude while they came there some of the stuff they kick, some of the stuff they break like so, which is.they are not allowed to do that I think so. (Alicia)

and

December I, I did get a big fight with the traffic.. mysef.. .and it's those kinds of things I don't like to do but I did them because they push me over and I did hurt myself. (Susanne)

All the women had traded without permits at some stage in their journey and they described their experiences of criminalisation and mistreatment as illegal vendors. Precious' states:

People like us foreigners who prefer to have legal things but because there's... we don't have any choice, we need to survive; We are like criminals but we are not doing anything wrong

Camilla reported that

During the world cup so everything must be beautiful because Cape Town is the Cape Town ...and then they didn't want us there because we look like lappies [loose rags], lappies like everybody's got different colours of these sails [messy appearance of loose rags] and so.

The women described how the restrictive local street trade legislation, harsh law enforcement approaches, lack of government support and the no security of tenure served as political barriers. According to Alicia:

We have stalls there [station deck].and Intrasite took the land back and we was without work..

and

... we tell them 'you supposed to tell us also we need to close early because we didn't know, we used to close here in December if its 7 o'clock no one come and complain, don't just come and fine us like that', they must also know we need also the notice before we do anything.

Camilla exemplified the limited participation of street traders in the municipal systems that govern street trade.

Uh-uh they [government] never ask us anything, they dictate it to us. That's where that comes in.

Other tough conditions included high levels of competition, an unpredictable market and harsh weather. Precious and Suzanne reported:

Around at the taxis there are a lot of vendors, so many, almost about a thousand trying to survive so you know what you are putting yourself into you have to be prepared.

"Sometimes it's [the weather] very bad for us but we got no choice."

The women also reported that their well-being was affected both positively and negatively by 'being in the same boat'.

We're in the same boat

The final category, 'We're in the Same Boat', spoke to the meaning, advantages and disadvantages of interconnectedness. Intercon-nectedness refers to the social connection, belonging, solidarity and affinity that traders valued with others they encountered in their work contexts. A complex relationship existed between the meaning and cost of a connected social identity. Alicia stated:

We [neighboring traders] sitting here like family, like friend, like brother and we like to make the jokes with each other.

We come also from the same village sometime we like to speak the language and its make us laugh because it's long time we didn't hear that dialect.

This allowed the women to

.help each other financially and become better people, all of us (Suzanne)

Interconnectedness enabled them to view periods of poor business differently.

...today is not my day, is somebody's day maybe is that guy's day. If that guy is selling selling, selling I'm happy, it's his day, tomorrow it's gonna be my one! (Alicia).

Collective prosperity was prioritised over personal financial gain so that meaningful connectedness with both family and acquaintances could be maintained. Camilla pointed out:

Sometimes like yesterday...I made uh...yesterday I only made a R5 for my sister...did I make money for me? (pause)...no...I didn't. I didn't make money for me but I made a R5 for my sister - I sold a toothbrush. I sold, I made a R245 for my daughter, selling Avon

Susanne recognised the strength of their collective participation..

Because all of us we need money, we have to understand each other. It's not-you mustn't think about yourself you have to think about the next person that is near you, that person needs to survive as well.

The women supported each other in multiple ways. They found strength and a sense of well-being in their shared intentions to work towards lives that they valued.

DISCUSSION

The women participated in street trading as a productive occupation despite the systemic social, political and economic challenges that they faced. Since many of the women's circumstances were marked by inter-generational poverty, informal street trading enabled the women to construct patterns and dispositions in their participation (that is, habits) that reflected their meaning-making processes. These habits were reflected, for instance in the way that the women's family heritage influenced their belief that street trading could benefit them and lead them towards living a valued life. Also, given that the women street traders had little training, education and work experience, street trading emerged as the most viable option for each of them. However, their aspirations were shaped by their socio-histories, but not necessarily determined by it27.

Street trading enabled the women to continuously adjust their actions to the situations that they confronted, allowing them to meet their occupational needs and survive from day to day. For example, the flexibility associated with being self-employed enabled the women to meet multiple needs within their productive, reproductive or community maintenance roles. The ability to meet these needs enhanced their experiences of well-being 28.

Capabilities, creativity and development

The women demonstrated their agency to act in and on their situations, for example, to fulfil their roles as mothers, partners, provide for themselves and their families and to be able to experience a sense of belonging with fellow street traders. Thus, through drawing on the opportunities and benefits afforded through their street trading they could imagine future possibilities22. Street trade afforded them opportunities to realise functionings19 crucial for the freedom to live the lives they valued - such as a sense of belonging through their collective purpose and sharing between women street traders. Their well-being unfolded through the ways in which they actively and creatively made the most of the opportunities that they encountered20,29. Furthermore, their continued participation in street trading allowed the women to meet their needs for survival, through providing a family income and opened up the possibilities for future occupations in which they could generate an income. These visions of possible future opportunities16 to participate in occupations fueled the women's continued participation and agency. The opportunities the women saw and took hold of may be likened to 'situations', or "transitions to and possibilities for later experiences"30. However, the women encountered limited freedom for achieving well-being through their available options and this has implications for their human development.

True to Kuo's31 description of human occupation, street trading is a means for creative improvisation towards desirable ends. Kuo31suggests that creativity and imagination about future possibilities leads to transactions that foster meaningful experiences. Similarly, the women's ability to uncover positive opportunities amidst difficult circumstances illustrates creativity towards meaningful, desired ends. Creativity (in the form of intelligence and imagination) surfaces when individuals deliberate on possible courses of action32. Through imagining possibilities towards the lives they valued and deciding on best possible actions for them, the women were able to creatively steer their lives towards well-being, despite difficult situations. Thus, creativity enhanced ongoing action towards well-being. According to Robeyns20, the valuable options - such as the positive opportunities the women imagined - are what truly count in creating freedom for well-being. Imagining is an endeavor beyond the conventional in order to creatively tap into new possibilities allowing people to be positioned as capable, resilient and pushing boundaries as they journey towards who they are becoming33. Through imaginative use of the resources available to them, such as public space, media and relationships, the women were able to accrue and to learn and practice business skills.

While street trading afforded the development and expression of capabilities towards well-being, the ethnographic inquiry reflected a limited range of valued possibilities towards well-being. The opportunities afforded to the women did not necessarily result in the effective and consistent ability to live valued lives. Galvaan34suggests that the existence of the opportunity to participate in occupations may not translate into actual occupational performance. Similarly, taking hold of opportunities and developing capabilities towards meaningful participation in street trading may not translate into enhancing occupational performance given the extent of influence of political and economic systems12. The challenging contextual conditions described by the women street traders underline how context impacts the freedom to live the lives they valued.

Occupational injustice, development and well-being

The restrictive contextual situations hindered the women's ability and freedom to achieve harmonious transactions and enhance their well-being through street trading. Restrictive conditions, such as the by-laws, resulted in occupational injustices and the impingement of certain freedoms, having negative implications for experiences of well-being.

Applying principles of human rights recognises that everyone should be afforded to "the ability and conditions needed to achieve one's purposes by action"35:386. However, the findings of this study showed that the difficult conditions that the women encountered while street trading affected the fulfillment of their potential well-being. The prevalent, dominant political and economic structures reinforced social norms in which women street traders were viewed as criminal and disenfranchised. The result was reflected in their limited ability to improvise their dispositions, based on important social values such as family legacy, through street trading towards well-being. Occupational injustice was experienced through systems that reinforce habits reflecting individualism36, falling outside of the social connectedness informing the women's actions. This creates conditions in which the women experience limited choice and control within their occupational participation of street trading. Occupational injustice restricted the extent of freedom to live, with dignity, the lives that they value. It also limited their ability to functionally coordinate their social, economic and political environments in order to optimize their well-being13. Thus, the occupational injustices the women street traders face affect their ability to engage in street trading in ways that foster well-being and development beyond marginalization.

IMPLICATIONS FOR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

Knowledge gained about informal work, such as street trading in local contexts can inform contextually responsive occupational therapy practice. Enhancing conceptions of informal work leads to further understanding the relationship between participation in occupations, well-being and development. Aligning with a critical practice of occupational therapy, the significance of social connectedness in shaping the women street traders' actions and ends-in-view suggests room for generating knowledge around the meaning and influence of collective participation on work occupations, particularly in the informal sector. While the influence of collective occupations37 has been considered, we believe that the profession has yet to explore the deeper, nuanced understandings of the connections between human occupation, collective occupations and well-being38. This is supported by the call for a practice that addresses transactions between social contexts and human occupation17,39,32.

Addressing the occupational injustices experienced by those engaging in street trading and other informal sector occupations will require challenging the hegemonic structures that reproduce the limited choice, control and marginalisation associated with participation in certain occupations. Occupational therapists should join advocacy efforts towards policy reform and legislation that addresses the conditions of informal work13. This may involve lobbying for workers' involvement in policy affecting their occupational lives and well-being. It may also include raising awareness about the issues of occupational consciousness and foster transactions with context that promote functional co-ordination with their environment. This includes how well-being and development may be promoted through widening opportunities for income generation and economic productivity40.

LIMITATIONS

While this study provides a description of a small group of women street traders in a city, it provides insights into the complex relationship between street trading and well-being. Therefore, although the findings are not intended to be generalizable, it offers focused insights into the challenges and triumphs encountered by women street traders who participated and offers possibilities for future research.

REFERENCES

1. Devey R Skinner C, Valodia I. Definitions, data and the informal economy in South Africa: a critical analysis. The Development Decade? Economic and Social Change in South Africa, 1994-2004. 2006: 302-23. [ Links ]

2. Alfers L, Xulu P Dobson R Hariparsad S. Extending occupational health and safety to urban street vendors: reflections from a project in Durban, South Africa. NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy. 2016; 26(2): 271-88. [ Links ]

3. Roever S. Informal trade meets informal governance: Street vendors and legal reform in India, South Africa, and Peru. Cityscape. 2016; 18(1): 27. [ Links ]

4. Statistics South Africa. Informal sector in South Africa. Survey of Employers and the Self-Employed (SESE). Pretoria; 2013. [ Links ]

5. Roever S, Skinner C. Street vendors and cities. Environment and Urbanization. 2016; 28(2): 359-74. [ Links ]

6. Woodward D, Rolfe R, Ligthelm A, Guimaraes P The viability of informal microenterprise in South Africa. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship. 2011; 16(01): 65-86. [ Links ]

7. Rockerfeller Foundation. Health vulnerabilities of informal workers. 2013. [ Links ]

8. Aldrich RM. A review and critique of well-being in occupational therapy and occupational science. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 18(2): 93-100. [ Links ]

9. Jakobsen K. If Work Doesn't Work: How to Enable Occupational Justice. Journal of Occupational Science. 2004;11(3): 125-34. [ Links ]

10. Stone SD. Workers Without Work: Injured Workers and Well Being. Journal of Occupational Science. 2003; 110(1): 7-13. [ Links ]

11. Ross J. The Meaning and Value of Work. Occupational Therapy and Vocational Rehabilitation: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008: 33-49. [ Links ]

12. Stadnyk R, Townsend E, Wilcock A. Occupational Justice. In: Christiansen C, Townsend E, editors. Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2010: 329-58. [ Links ]

13. Mitullah WV. Street vending in African cities: A synthesis of empirical finding from Kenya, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa. World Development Report background papers. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005. [ Links ]

14. Dickie V. Cutchin MP. Humphry R. Occupation as Transactional Experience: A Critique of Individualism in Occupational Science. http://dx.doi.org/101080/1442759120069686573. 2011; 13(1): 83-93. [ Links ]

15. Aldrich RM. From complexity theory to transactionalism: Moving occupational science forward in theorizing the complexities of behavior. Journal of Occupational Science. 2008; 15(3): 147-56. [ Links ]

16. Cutchin M, Aldrich R, Baillard A, Coppola S. Action theories for occupational science: The contributions of Dewey and Bourdieu. Journal of Occupational Science. 2008; 15: 157-64. [ Links ]

17. Cutchin MP. Dickie VA. Transactional Perspectives on Occupation: An Introduction and Rationale. In: Cutchin MP, Dickie VA, editors. Transactional Perspectives on Occupation. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2013: 1-10. [ Links ]

18. Sen A. Wellbeing, Agency and Freedom. Journal of Philosophy. 1985; 82(4): 169-221. [ Links ]

19. Sen A. Development as freedom: Oxford Paperbacks; 2001. [ Links ]

20. Robeyns I. The capability approach: a theoretical survey. Journal of human development. 2005; 6(1): 93-117. [ Links ]

21. Anand P, Hunter G, Smith R. Capabilities and well-being: evidence based on the Sen-Nussbaum approach to welfare. Social Indicators Research. 2005; 74(1): 9-55. [ Links ]

22. Wilcock AA. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1999; 46(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

23. City of Cape Town. City of Cape Town: Informal Trading By-law. Province of Western Cape: Provincial Gazette; 2009. [ Links ]

24. Statistics South Africa. Census 2011:Statistics release P0301.42011 02 July 2015. Available from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03014/P030142011.PDF. [ Links ]

25. McCurdy DW, Spradley JP, Shandy DJ. The cultural experience: Ethnography in complex society: Waveland Press; 2004. [ Links ]

26. Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002; 17(1): 13-26. [ Links ]

27. Social Law Project. Street Vendors' Laws and Legal Issues in South Africa. Cambridge, MA: USA: WIEGO; 2014. [ Links ]

28. Doble SE, Santha JC. Occupational Well-Being: Rethinking Occupational Therapy Outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 75(3): 184-90. [ Links ]

29. Robeyns I, Brighouse H, editors. Introduction: Social primary goods and capabilities as metrics of justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [ Links ]

30. Dewey J. The school and society. Southern Illinois: SIU Press; 1980. [ Links ]

31. Kuo A. A transactional view:Occupation as a means to create experiences that matter. Journal of Occupational Science. 2011; 18(2): 131-8. [ Links ]

32. Galvaan R, Peters L. Occupation-based community development framework. 2013.Available from: www.opencontent.uct.ac.za [ Links ]

33. Reed K, Hocking C, Smythe L. The interconnected meanings of occupation: The call, being with, possibilities. Journal of Occupational Science. 2010; 17(3): 140-9. [ Links ]

34. Galvaan R. The Contextually Situated Nature of Occupational Choice: Marginalised Young Adolescents' Experiences in South Africa. Journal of Occupational Science. 2015. [ Links ]

35. Hammell H, Iwama M. Wellbeing and occupational rights: an imperative for critical occupational therapy. Scandanavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 19: 385-94. [ Links ]

36. Dickie V Cutchin MP Humphry R. Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science. 2006; 13(1): 83-93. [ Links ]

37. Ramugondo E, Kronenberg FF Explaining collective occupations from a human-relations perspective: Bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science. 2015; 22(l): 3-16. [ Links ]

38. Hammell KW. Sacred texts: A sceptical exploration of the assumptions underpinning theories of occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009; 76(1): 6-13. [ Links ]

39. Galheigo SM. What needs to be done? Occupational therapy responsibilities and challenges regarding human rights. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011; 58(2): 60-8. [ Links ]

40. Von Broembsen M. Informal business and poverty in South Africa: Rethinking the paradigm. Law, Democracy & Development. 2010; 14(1). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sharyn Sassen

sharynsassen@gmail.com