Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.48 no.1 Pretoria abr. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol48n1a4

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

An exploration of the roles and the effect of role expectations on the academic performance of first year occupational therapy students: a University of the Free State case study

A SwanepoelI; SM van HeerdenII

IB OT (UFS), M OT (UFS), Junior Lecturer, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Free State

IIB OT (UFS), M OT (UFS), PhD HPE (UFS), Occupational Therapist in private practice, Bloemcare

ABSTRACT

First-year students in occupational therapy enter higher education and take on different roles while engaging in occupations such as academics, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and social participation. Some of the roles are new and pose challenges to students which in turn influence their academic performance. A qualitative research approach was applied by making use of a case study research design to explore possible factors that influence the students' academic performance. Eighteen first-year occupational therapy students from the University of the Free State were randomly selected to take part in the study. Data were collected from documentation and Nominal Group Technique discussions. The aim of this article is to report on some of the significant findings from the initial study, namely the roles students adopt to meet the challenges during their first year at university. Four roles were identified: role of a student, role of an independent young adult, role of a friend and role of a member of a campus residence. The identification of these roles should make educators take note of the need for support to the first-year student on a departmental as well as faculty level.

Key words: Academic performance; First-year Occupational Therapy students; Occupational engagement, role fulfilment

INTRODUCTION

Engaging in meaningful occupation is part of an individual's everyday life1. Furthermore, by engaging in such occupations, individuals adopt different roles, each with its own expectations2. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF)1 was used in this study to describe roles and role expectations of first-year occupational therapy students. Although OTPF was designed as a therapeutic tool, it can also be used as a method to understand an individual's performance patterns in all contexts, even in the absence of disease or disability.

The role expectations during the first year in higher education are characterised by an adjustment period with new academic, social, and emotional challenges3,4,5. Likewise, first-year occupational therapy students start to engage in different higher education occupations where new roles are also adopted, which in turn impose social and academic demands on them6. Many of these role demands have a negative influence on the academic performance of students in the Occupational Therapy programme at the University of the Free State (UFS)6.

Reports in the literature4,7,8 have indicated academic-, personal-, cognitive- and social factors, among others, to have an influence on the academic performance of first-year students. However, these factors are typically discussed in isolation, creating a gap in the literature with no inclusion integration of possible academic performance factors. A study was conducted to explore all the possible factors influencing first year occupational therapy students' academic success5. In this article, the author attempted to illustrate the relationships between the roles students adopt and the subsequent factors influencing academic performance that were identified as a theme in the above mentioned study.

Findings showed that adopting different new roles proved to be a challenge to first-year occupational therapy students.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The higher education environment offers a variety of new occupations in which first-year students engage. Wilcock9:4 referred to this meaningful engagement in activity as "doing", which she perceived as synonymous with "occupation". In doing or engaging in academic occupations, students will adopt different roles, some of which are new. These life roles are "sets of behaviour expected by society and shaped by culture and context..."2.

Hitch, Pepin and Stagnitti10 emphasised the relationship between meaningful role fulfilment and occupational engagement, particularly when a role contributes to the social identity of a student. However, these roles influence and are influenced by the occupation of education, and all the relevant activities students have to engage in. First-year students are consequently confronted with extreme and constant change in their daily lives.

The occupations students engage in that are significant for the aim of this article, are academic occupation, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and social participation. These occupations are discussed below.

Academic occupations

Students enter the higher education environment with various expectations regarding their lives and experiences at university. They envision their new journey filled with freedom to have fun, meet new friends and having stimulating academic experiences4,11. Kan-tanis4 pointed out that students who have realistic expectations of their HE experience, tend to be more successful. Yet many students start their studies without clear expectations of the responsibilities and demands they will need to negotiate. This quickly changes once they start engaging in formal academic occupations. One such demand is to manage the large workload in higher education. Various authors3,4,8 identify workload as a possible factor that negatively influences academic performance. Coping with the large volume of work is a reality that overwhelms the first-year student. Adjusting to the faster pace of the new learning environment poses another challenge to the first-year student3.

To succeed, students need to be motivated to engage in the academic environment3, as well as be adequately prepared11 for academic skills such as correct study methods and time management. Lowe and Cook7 reported that students follow the same study habits during the first six months of their university career as they did at school. However, students then realise that these study methods are ineffective. Furthermore, Busato et al.12 and McGuire13have identified study methods, learning styles and intellectual abilities as factors that influence academic performance.

In addition, the higher education environment also requires students to adopt an independent learning focus7. Not only is the pace much faster, the first-year student now also has to take full responsibility for their engagement in academic occupations. Additionally, there are no extra classes in modules that may assist a student to improve his or her academic performance, as might have been the case at school. The first-year student is now responsible for his/her own learning process and has to manage it by making use of support structures provided by higher education4. To be able to meet the academic demands, life skills such as time management, self-discipline, and perseverance are put to the test during the first academic year of many students7.

To ease the adjustment, Kantanis4 encouraged students to get involved in, and engage with other students in the same learning environment. The support from fellow students, mentors and faculty members was found to have a positive influence on academic performance of first-year students6.

Instrumental activities of daily living

Many students leave home to study at higher education institutions, often far from home and their known environment7. Responsibilities of independent young adults must be taken on, although they are still in the late adolescence phase of their development. Subsequently, they experience IADL challenges such as managing their own finances, grocery shopping, meal preparation, and doing their own laundry2,14, all of which are time consuming. These expectations present much larger challenges than what they had anticipated and exacerbate the already heavy academic workload that has to be managed14.

Social participation

Social participation is defined as: "Organised patterns of behaviour that are characterised and expected of an individual or a given position in a social system"1:633. The first-year student is not only a member of a student body, but also a member of a social community at university. This community includes the student's physical and social environments2, whether it be one friend, a group of friends, classmates or fellow residence students. The social community has certain expectations of first-year students. Students who live on campus (in residences) are required to participate in all residence activities despite a busy academic programme6.

Social participation is a fundamental component of the Millennial generation. Millennials are the cohort born during the mid-1990s to early 2000s15. The Millennials are more social and being part of a group is very important to them16, which in turn meets their need of belonging, according to Maslow's hierarchy of needs17. This might be problematic to the first-year occupational therapy student. Having to meet the demands of a heavy loaded academic programme, as well as the social demands of the community, may have a negative influence on their academic performance.

However, Dixon, Rayle and Chung18 reported a positive relationship between first-year students' social support structures, a feeling of belonging and academic performance. It is clear that numerous demands are placed on the first-year student. In addition to the academic demands, they are also faced with a demand for independence in activities of daily living and social participation responsibilities.

METHODOLOGY

The original study from which this article was derived, explored the factors which play a role in the academic success of first-year occupational therapy students at the UFS. The analysis of the data obtained from this study (the methodology of which is outlined below), revealed clear roles adopted by students in their first year. Only the findings pertaining to these roles will be discussed in this article.

The original study followed a qualitative approach, and a collective case study design was applied19,20. This study design was chosen for the value it adds for in-depth study21 of one or more cases in a group or system, and because of its explorative nature. This has clearly been illustrated by Creswell22, where multiple cases are involved in one point of interest. The group of participants (in this case the group of first-year occupational therapy students), were viewed as one case.

The Sample

Random sampling was used to select participants from a list of English- and Afrikaans-speaking first-year occupational therapy students registered for the first time at the UFS in 2013. A total of eighteen (18) students - nine English- and nine Afrikaans-speaking students, were selected. As the academic achievements were varied throughout the class, a random sample was needed to have representation of all students.

Data collection and analysis

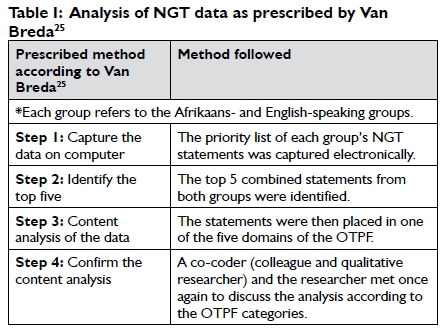

Two Nominal Group Technique (NGT) discussions and documentation data were used to collect data in the study19,23,24.

NGT discussion is a method of collecting data during a group discussion with priority lists as an end-product to the discussions24. By answering a question, the group discusses and prioritises the most prevalent answers and opinions derived during the discussions. This is one of the benefits of NGT discussions and the reason it was chosen as a method to collect data in this study.

Two NGT discussions took place on separate occasions. A person with experience in NGT discussions facilitated the English- and Afrikaans- speaking groups. During the two NGT discussions, the following questions were posed to the students by the facilitator:

✥ Which factors positively influence your academic success in the first year of occupational therapy?

✥ Which factors negatively influence your academic success in the first year of occupational therapy?

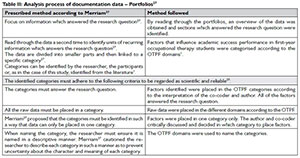

An adapted multiple group NGT data analysis, as described by Van Breda25, was used to analyse the two sets of data. Steps one to four of the process were followed, and due to the qualitative nature of the analysis, steps five and six were excluded.

Documented data were collected from two sections of the first-year occupational therapy students' portfolio reflections. Portfolios were submitted twice a year and assessed by members of staff in the Department of Occupational Therapy. After the assessment was completed, the researcher analysed the reflections of all 18 participants.

The students firstly reflected on factors influencing their academic performance in the first-year by making use of the Kawa River Model26. In addition to the Kawa River Model reflections, they also reflected more specifically on their study and test-writing skills and possible factors that influenced test and examination results.

In the Kawa River Model26 the river bed and river banks are described as the physical and social environment within which the individual functions26. It is also in this environment where the students engage in meaningful occupation by adopting specific roles.

The rocks in the river represent life and the challenges that the individual has to face26.

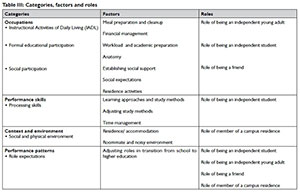

Documentation data obtained from the portfolios were subsequently analysed thematically19,27 by grouping similar categories of data together. The five domains of the OTPF2, namely Occupations, Client factors, Performance skills, Performance patterns and Contexts and environment, were then used as categories and sub-categories of the factors influencing academic performance of first-year occupational therapy students, as identified from the portfolios1. The domains of the OTPF do not necessarily provide answers to the research question. The framework does however, describe the occupational engagement holistically, which served as a deciding factor in choosing the domains of the OTPF as categories in the analysis process. (See Table II below.)

Trustworthiness and credibility

Trustworthiness and credibility of the study were established with regard to the researcher and the research method. In addition, a complete research proposal was peer-reviewed and approved.

Triangulation was used to increase the credibility of the research study28. Firstly, data triangulation was used. Different types of data were collected from the portfolios (documentation) and two sets of data were collected from the two NGT discussions. Data collection took place over a period of approximately one year.

Secondly, investigator triangulation was applied28 by making use of a facilitator and a co-coder. An experienced facilitator conducted the NGT discussions. The researcher was present during the process and acted as the scribe. This ensured a good understanding of the factors identified by the participants. Co-coding was done to ensure that researcher bias was limited.

Finally, method triangulation23 was used. Method triangulation offers the researcher the opportunity to make use of more than one method of data collection. This in turn allows the researcher to test the findings from the different methods comparatively. As with data triangulation, method triangulation was achieved by following a case study research design where findings were acquired from documentation and the NGT.

The veracity of the data was ensured through member checking. The facilitator of the NGT discussions presented the factors influencing the students' academic achievements positively and negatively19 to the participants. This was done with both the Afrikaans- and English-speaking groups on the separate occupations to confirm that all the participants agreed on the factors identified.

The interpreted findings were presented to the Department of Occupational Therapy where the participants were present.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the UFS granted ethical clearance for this study29 (ECUFS 72/2013). Participation in the study was voluntary and participants had the choice to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants had no financial or academic gain during or after the study. The facilitator encouraged the participants to keep all discussions confidential to ensure their privacy as far as possible. However, privacy could not be guaranteed during the NGT discussions due to the nature of the process.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The five domains of the OTPF were used as categories and sub-categories for the study. Factors mentioned by students as either negatively or positively affecting their performance in each domain were then identified, where after the roles associated with each factor were allocated. A summary of the categories, associated factors and roles adopted within each category (as identified by students) is shown in Table III on page 19.

IDENTIFIED ROLES AND EXPECTATIONS

Role of being an independent student

Being a student in the first year of the programme is challenging. Students are soon confronted with the challenge of a much larger workload than what they were used to at school. This was a reality for students 1 and 7.

I realised the workload was a lot more than school... (Student 7)

...the workload and academic pace of university pose a big stumbling block and adjustment... (Student 1)

The large volume of work, which needs to be read, comprehended and studied in a fairly short period of time, poses real challenges to students4. Friedlander et al.3 identified the workload, among other factors, as a possible negative factor that influences academic performance. Different authors4,10 concurred that the higher education workload is much larger than what the students were used to in school. Furthermore, the lectures occur at a much faster pace and cover more work per contact session4 than what first-year students were accustomed to. In addition, the higher education academic calendar differs from the school calendar with less contact time between students and lecturers and a much higher load of subject material to be covered.

Students who are selected for the occupational therapy programme at the UFS are selected mainly on their academic abilities. The inference is thus that students made use of effective study methods at school. Unfortunately, the methods they used are not always effective in higher education.

I will seriously have to start working on a new study method now that the volume of work is increasing exponentially. (Student 3)

The statement of student 3 illustrates the sentiment of the majority of participants' need to change their study method. The students' reflections seemed to echo the statement by Lowe and Cook7 that many first-year students only realise their study methods are inadequate after the first semester in higher education.

Once the students enter the higher education environment they are expected to function as independent learners30. This seemed to be a challenge for student 15, because in higher education she had to take responsibility for her own learning.

The world where decisions are mostly made for us and where everything seems to go our way is definitely one of the past. (Student 15)

At school, students are taught in a teacher-centred environment. This means that all learning activities are directed by the teacher30. For students to embrace the student-centred learning environment, self-directed learning should be adopted.

There is consensus in the literature that students in higher education need to adopt an independent learning approach30,31,32, thus taking on the role of being an independent learner. The independent learner presents with the following characteristics:

Firstly, the learner is able to take control of his/her learning30,31. Students must realise that a change is needed in their study methods in order to cope with the academic demands of the programme. They must decide "when, where, what and how" to study31. In order for the student to take control of his/her studies, he/she must also be able to develop a personal learning plan31 and reflect on his/her learning process33.

A second attribute of an independent learner is to take responsibility for his/her own learning31. Students realise that lecturers will facilitate their learning, but they are responsible to make sure that they engage with the academic content that was presented to them.

Role of being an independent young adult

Several students leave home to study at a university and experience IADL challenges. "Adult independence" as expected from adults is a new reality for students entering higher education8.

At this stage I also started to realise just how big my new responsibilities were: I had to manage my own finances, had to cook for myself... (Student 9)

Far from home, self-care activities take up time. (NGT statement)

The student who resides in campus accommodation or in a student house must now take care of her-/himself. This is often a new role expected from the students. Unfortunately, home man-agement tasks such as health management, grocery shopping, meal preparation and clean-up, are time-consuming and take up time that students would rather spend on academic activities.

A number of students needed to manage their own finances and voiced it as a stressor.

Financial stress - managing my finances... food and living expenses are very expensive and are cutting my budget short (Student 15)

Many students receive an allowance, and have to manage their finances to accommodate both living and additional academic expenses. This can cause stress for the first-year student, thus influencing their academic performance34,14,18. Pancer et al.14 confirmed the influence of managing their own finances, something which was done for them when they stayed at home. Buying groceries, filling their vehicles with petrol, buying clothes, snacks, etc., must all be managed by the students themselves, with no parents to fall back on for financial assistance when shortages on their budgets are experienced.

Role of being a friend

Students move out of the known school environment where social connections were made over several years. Consequently, they experience the loss of school friends who are studying elsewhere or in other programmes.

I was also excited to meet new people, but sad to leave my old friends(Student 6)

Yet first-year students face the social expectations of making new friends and enjoying the new freedom university life brings4. Friendships established in higher education is not only between students in the same first-year class, but is also established in residences.

My friends, the ones that study other courses, do not really understand what exactly it entails to be a first-year OT student. Due to this, I have lost contact with many friends. (Student 9)

Friends in programmes less challenging may place social demands on the occupational therapy student. Due to the heavy workload, students are not always in the position to meet the social demands of engaging with their new friends as often as they would like to. First-year occupational therapy students often find themselves in a conflicting position where, on the one hand, friendships are important, but on the other hand, the workload of the academic programme prevents socialisation.

I have a good... environment filled with love from my family and friends, the old friends and the new friends. (Student 8)

Nevertheless, it is important for the students to establish a new social support system8,18. Fortunately, as student 8 pointed out, some students are able to establish new friendships while maintaining old ones. Social contact and social support are high on the Millennial generation's priority list16,35. For the adolescent, it is very important to establish friendships19. "Without friends, students have fewer resources at their disposal to assist them in the process of transition to university life."4. As mentioned, the literature18 emphasised the value of social support, which brings about a sense of belonging to first-year students and as a result, eases their adjustment to the academic environment. This in turn has a positive influence on the student's academic performance.

Role of member of a campus residence

Being a member of a campus residence is deemed an important factor influencing academic performance in more than one way, and is the cause of stress for many students7.

Hostel activities kept me very busy and the seniors do not want to understand that I must study, because they feel everybody write tests not just me. (Student 4)

Engaging in residence activities, such as rag, "sêr" (serenade), stage door and lengthy residence meetings, is compulsory and can be time consuming for first-year students. "Sêr" and stage door are two platforms where residences compete in small group singing competitions. This is time-consuming as members of the groups have regular compulsory rehearsals.

I am very involved in my hostel's activities and this causes problems with my time management and endurance. (Student 10)

For the student facing increased academic demands, lengthy residence meetings add to existing levels of stress. Furthermore, students might not have made the transition to self-directed learning yet, and consequently fail to take responsibility for their learn-ing30,31,32. Students receive timetables and a residence programme in advance and can use this information to assist in planning ahead for busy times. The first-year student who did not acquire time management skills in secondary school, will find it challenging to organise their time.

In addition to the activity demands placed on students in residences, the physical environment is at times not conducive to studying. Dusselier et al.34 reiterated the negative influence that conflict between roommates and the noisy environment have on academic performance of students staying in campus residences.

Res is a noisy place which is a very negative experience for me. (Student 4)

The residence is students' home away from home. It is understandable that students want to relax, play music and visit with their friends in the residence rooms. Regrettably, not all students might be equally accommodating towards fellow students' study needs.

First-year occupational therapy students are in the process of becoming Occupational Therapists and independent adults. However, Hitch et al.10 acknowledged that becoming an adult is an ongoing process of change, occurring in a social environment with a variety of people in the students' lives. By being a student and meeting the demands set out above, a student's transition towards becoming an independent adult is mediated.

LIMITATIONS

A limitation of the study was the randomised sampling. A criterion sampling method is advised for a study of this nature where academic performance is explored. During the planning phase of the study it was decided to use Anatomy marks as indicative of academic performance. However, when sampling had to be done, the students' first semester average marks for Anatomy were not yet available, and consequently, randomised sampling had to be used. The lack of gender and race diversity was a further limitation of the study.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this article was to describe the roles that first-year occupational therapy students adopt once entering higher education, and their perceptions of associated factors influencing their academic performance. The findings described the different roles adopted by the first-year occupational therapy student and the consequent challenges posed by these roles. The value of and need for friends and social support was evident. Yet, the heavy workload of the academic programme hinders students' engagement in much needed social participation occupations. As independent young adults, they now have to manage time-consuming IADL tasks amidst a full academic programme. This article has not only reiterated the influence of the different roles adopted by first-year occupational therapy students, but also the role conflict that exists and the influence thereof on the academic performance of these students. As educators of the next generation of therapists, we need to take note of the challenges they have to face. The author recommends that students should be made aware of support structures available at training institutions. Academic time tables can be planned to accommodate the first-year students during the initial adjustment period.

REFERENCES

1. AOTA. (American Occupational Therapy AAssociation). Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process 2nd ed. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 62: 625-645. [ Links ]

2. AOTA. (American Occupational Therapy Association). Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process 2nd ed. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 68(1): s4-s28. [ Links ]

3. Friedlander LJ, Reid GJ, Shupak N and Cribbie R. Social support, self-esteem and stress as predictors of adjustment to university among first-year undergraduates. Journal of College Student Development. 2007; 48(3): 259-270. [ Links ]

4. Kantanis T. The role of social transition in students' adjustment to first-year to the first year of university. Journal of Institutional Research. 2000: 1-8. [ Links ]

5. Sevni S and Gizir CA. Factors negatively affecting university adjustment from the view of first-year university students: The case of Mersin University. Educational Sciences: theory and practice. 2014; 14(4): 1301-1308. [ Links ]

6. Swanepoel A. Factors influencing academic success of first year occupational therapy students at the University of the Free State. M Occ Ther dissertation. Dept of Occupational Therapy. University of the Free State; 2014. [ Links ]

7. Lowe H and Cook A. Mind the Gap: are students prepared for higher education? Journal of Further and Higher Education. 2003; 27(1): 53. [ Links ]

8. Nel C, Tronskie-de Bruin C and Bitzer E. Students' transition from school to university: Possibilities for a pre-university intervention. SAJHE. 2009; 23(5): 974-983. [ Links ]

9. Wilcock AAA. Reflection on Doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1999; 46: I-II. [ Links ]

10. Hitch, D. Pepin, G. & Stagnitti, G. In the footsteps of Wilcock, Part One: The evolution of doing, being, becoming and belonging. Occupational Therapy In Health Care. 2014; 28(3): 231-246. [ Links ]

11. Strydom JF, Mentz M and Kuh GD. Enhancing success in higher education by measuring student engagement in South Africa. Acta Academica. 2010; 2. [ Links ]

12. Busato V V Prins FJ, Elshout JJ and Hamanker C. Intellectual ability, learning style, personality, achievement motivation and academic success of psychology students in higher education. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000; 26(6): 1057-1068. [ Links ]

13. McGuire SY The impact of supplemental instruction on teaching students how to learn. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. Wiley Inter Science, 2006; 106: 3-4. [ Links ]

14. Pancer SM, Hunsberger B, Pratt MW and Alistat S. Cognitive complexity of expectations and adjustment to university in the first year. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000; 15(1): 38-57. [ Links ]

15. Twenge JM. Generational changes and their impact in the classroom: teaching Generation Me. Medical Education. 2009; 43: 398-405. [ Links ]

16. Nimon S. Generation Y and higher education: The Other Y2K. Journal of Institutional Research. 2007; 13(1): 24-41. [ Links ]

17. Weiler A. Information-seeking behaviour in generation y students: Motivation, critical thinking and learning theory. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2005; 31(1): 46-53. [ Links ]

18. Dixon Rayle A and Chung K. Revisiting first-year college students' mattering: social support, academic stress, and the mattering experience. Journal of College student retention. 2007-2008; 9(1): 24, 30. [ Links ]

19. Cresswell JW. Research design qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. Third Edition. California: Sage, 2009. [ Links ]

20. Fouche CB and Schurink W. Qualitative research designs. In: de Vos AS, Strydom, H Fouche, CB and Delport CSL. Research at grass roots for the social and human service professions. Fourth Edition. Pretoria: Van Schaik; 2011: 322. [ Links ]

21. Flyvbjerg B. Case Study. In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The sage handbook of qualitative research. Fourth Edition. California: Sage; 2011: 307. [ Links ]

22. Creswell JW. Educational research planning, conducting and evaluating qualitative research. Fourth edition. Boston: Pearson, 2012. [ Links ]

23. Maree K. First steps in research. Revised tenth impression. Pretoria: Van Schaik; 2012. [ Links ]

24. Potter M, Gordon S and Hamer P The nominal group technique: A useful consensus methodology in physiotherapy research. New Zeeland Journal of Physiotherapy. 2004; 32: 126-130. [ Links ]

25. Van Breda AD. Steps to analysing multiple group NGT data. The social work practitioner-researcher. 2005; 17(1): 1-14. [ Links ]

26. Iwama MK Thomson N A and Macdonald RM. The Kawa model: The power of culturally responsive occupational therapy. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009; 31(14): 1125-1135. [ Links ]

27. Merriam SB. Qualitative research a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [ Links ]

28. Flick U. Triangulation in qualitative research. In Flick U, Von Kardorff and Steinke I. A Companion to qualitative research. London: Sage; 2004: 178 -183. [ Links ]

29. UFS EC 29. (University of the Free State). Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences. General Guidelines; 2012. [ Links ]

30. Amin Z and Eng KH. Basics in medical education. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 2003. [ Links ]

31. Dent JA and Harden RM. A practical guide for medical teachers. Second Edition. London: Elsevier; 2005. [ Links ]

32. Harden RM and Laidlaw JM. Essential skills for a medical teacher. An introduction to teaching and learning in medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2012. [ Links ]

33. UFS.(University of the Free State). Department Occupational Therapy. General Skills Portfolios; 2013. [ Links ]

34. Dusselier L, Dunn B, Wang Y Shelley MC and Whalen DF Personal, health, academic and environmental predictors of stress for residence hall students. Journal of American College Health; 2005, 54(I): 15-24. [ Links ]

35. Sandars J and Morrison C. What is the net generation? The challenges for future medical education. Medical Teacher. 2007; 29: 85,86. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Me A Swanepoel

swanepoela@ufs.ac.za