Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.47 no.3 Pretoria dic. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n3a5

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Occupation-based practice in a tertiary hospital setting: occupational therapists' perceptions and experiences

Lucia Hess-AprilI; Nicolette GanasII; Lungelo PhiriII; Pumza PhoshokoII; Lynique DennisII

IBSc OT (UWC), MPH (UWC), PGD Disability Studies (UCT), PhD (UWC)- Lecurer, Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Community Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape

IIBSc OT (UWC)- Fourth year students at the University of the Western Cape at the time of the study

ABSTRACT

Occupation-based practice is an important feature of occupational therapy. There is however limited research regarding occupational therapists' experiences with occupation-based practice. This study aimed to explore occupational therapists' perceptions and experiences regarding occupation-based practice in a tertiary hospital setting in the Western Cape, South Africa. An explorative and descriptive research design within a qualitative research approach was utilised. Purposive sampling allowed the selection of four participants with a minimum of 2 years practice experience. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to gain an understanding of how they perceived and implemented occupation-based practice. Data were analysed using thematic analysis. Four themes emerged: occupation-based practice expresses professional identity; occupation-based practice necessitates relevance; constraints to occupation-based practice; and facilitators of occupation-based practice. The findings revealed that the participants' perceived the implementation of occupation-based practice as an expression of their professional identity and that in adopting an occupation-based approach they perceived their roles as being diverse and transformational. It was however highlighted that the nature of the service context posed several constraints that influenced the implementation of occupation-based practice. Thus, occupational therapists may need to generate practice-based evidence to advocate for the service conditions necessary to implement occupation-based practice and deliver relevant occupational therapy services.

Key words: Occupation, occupation-based practice, teriary hospitals, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Occupation-based practice is regarded as an essential feature of occupational therapy practice1,2. Therefore, best practice in occupational therapy is considered to equate effective occupation-based enablement aimed at the attainment of health, well-being and jus-tice3,4 since people as occupational beings are affected by their life experiences and the opportunities and choices available to them4,5. Occupational enablement therefore becomes an important part of occupation-based practice and is defined as the process of working with people to develop their ability to engage in the occupations they need or choose to do, or by adapting their occupations or the environment to enhance their occupational engagement6.

However, occupation-based interventions are often perceived and experienced as a challenge by occupational therapists, due to constraints such as the predominance of the medical model in hospital settings7,8,9,10. Consequently, developing strategies to support the implementation of occupation-based practice could counter such constraints. Therefore, underpinning this study was the assumption that uncovering therapists' application of occupation-based practice within every-day practice could inform the development of strategies that may be necessary to support its implementation. There is furthermore a dearth of research in this area particularly in the South African context. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to explore and describe occupational therapists' perceptions and experiences of occupation-based practice in a tertiary hospital setting in the Western Cape. Additionally, the objectives were to explore factors that facilitate or constrain the implementation of occupation-based practice from the perspectives of the participants.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Occupation-based practice is generally understood as an intervention that supports clients' interests, needs, well-being, and participation in daily life through occupation11- This however does not imply a simplistic conceptualisation of occupation-based practice where it is only understood as merely the use of occupation in intervention but rather that clients' occupational choice is facilitated and that they are enabled to engage in occupation as a means towards realising identified occupational outcomes as an end2. The term 'occupation-based' refers to the use of occupational engagement as the actual assessment or intervention method12 as well as the outcome of practice for example occupational enablement, that matches the client's goals13 and meaningful occupations of his/her choice14. Hence, adopting an occupation-based approach to practice implies that practice enables occupational performance and engagement relevant to clients2. Consequently, occupation-based practice involves a repertoire of occupation-focused interventions which aim to enable people to do, be, and become according to their identified needs and goals15. Occupation-based practice may thus encompass interventions that range from the use of activity to restore impairment, to advocacy and mediation for the promotion of occupational justice to address contextual issues that influence occupational engagement13.

Several authors highlight facilitators of occupation-based practice16,17,9. For example, occupational enablement and client-centred approaches are central to occupation-based practice in order to ensure relevant services that fit clients' contexts14 as these approaches necessitate that occupation-based practice is focused on clients' needs, goals, values and interests in partnership with them16. Additionally, literature highlights contextual constraints such as availability of resources9,16 as well as medical model dominance9,10 that may influence the implementation of occupation-based practice. A qualitative study that was conducted to describe paediatric occupational therapists' perspectives on occupation-based practice in a medical facility in the Midwestern United States18 indicated that while occupation-based practice was found to be satisfying and rewarding, its implementation was experienced as being difficult due to resource constraints such as lack of time for planning, preparations and implementation as well as lack of availability of materials and equipment. It was further highlighted that lack of experience may also serve as a hindrance to occupation-based practice as therapists may be more familiar with component-focused intervention as it is considered to be easier to implement. Further constraints to occupation-based practice include occupational therapists' failure to use terminology that clearly defines what occupational therapists do12, resource constraints, and therapists' lack of understanding their clients' context19. Strategies proposed for occupational therapists to respond to these constraints include framing undergraduate and postgraduate curricula in an occupation-based approach, practicing in ways that promote thinking in an occupation-based manner and using occupational language in documentation19,20. In addition, engaging in scholarship activities and continued professional development events as well as the collection of appropriate evidence to enhance service outcomes is considered to be important in facilitating change in practice settings19,20.

METHODOLOGY

Study design

The research setting in this study was a tertiary hospital within the Metro Health district of the Western Cape that offers a full range of general specialist and sub-specialist services involving sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic technologies in the treatment of complex conditions. The researchers who were student occupational therapists at the time of this study selected this particular hospital as it served as their fieldwork placement and offered various practice areas in which students are afforded the opportunity to observe, practice and acquire experience in a diverse range of occupational therapy practice fields catering to individuals of all ages and stages from paediatrics to geriatrics. A qualitative exploratory and descriptive research design21,22,23 within the interpretive paradigm24 was used to explore the participants' perceptions and experiences regarding occupation-based practice in the hospital. The intention of interpretivist research is to understand the subjective and socially constructed realities of people, thereby knowledge regarding the perceptions, viewpoints and practice of the research participants could be generated24.

Participants

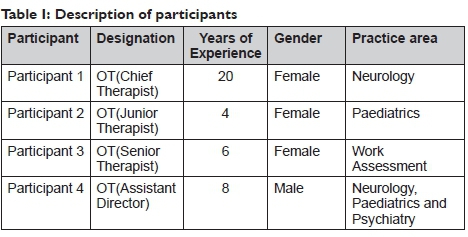

Purposive sampling24,25 was employed to select participants. Participants had to have a minimum of two years practice experience and had to be based in practice areas within the hospital setting that catered for individuals in at least one of the stages of childhood, adolescents, adulthood and older adulthood. A total of four occupational therapists from the population of eight therapists that were employed at the hospital at the time of the study met these criteria and consented to be part of the study. Participants included three females and one male and practiced in various practice areas including neurology, work assessment, paediatrics and psychiatry.

Their designations ranged from junior therapist to assistant director and their practice experience ranged from 4 to 20 years. See Table I for a description of the participants.

DATA COLLECTION

Semi-structured interviews

Data collection was conducted through individual semi-structured interviews which are non-standardised ways to collect data as well as to gain in-depth knowledge from individuals regarding their views, feelings, perceptions and/or experiences about research issues26. For the purpose of conducting the interviews, each of the four student researchers was paired with another researcher with one researcher leading the questions and the other taking notes. The focus of the interviews was on the participants' daily routines and activities, type and rationale behind occupational therapy services rendered and their understanding and implementation of occupation-based practice. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes to 1 hour and were structured around open-ended questions utilising an interview guide27 (See Table II). After each participant was interviewed once, data saturation was reached. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim in preparation for data analysis.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis28 was conducted. The four student researchers jointly engaged in the process which entailed five phases: 1) familiarising, which entailed each researcher reading and re-reading the transcripts to gain a rich understanding of the content; 2) line-by-line coding of transcripts by individual researchers to generate initial codes; 3) researchers jointly engaging in a search for similarities amongst codes and forming categories through discussion and consensus; 4) reviewing, defining and naming themes and 5) formulating a report representing the story of the data across all themes.

The analysis was critically reviewed by the first author who also provided close supervision of the complete process and provided input where necessary.

Trustworthiness

Credibility was ensured through peer examination and triangulation of data methods29. Peer examination occurred through maintaining a reflective journal kept by each researcher and engaging in joint reflexivity30 throughout the research process. Researcher triangulation occurred as four researchers jointly conducted data analysis31 while theoretical triangulation occurred through the review of relevant literature related to occupation-based practice29. Providing a thick description of the entire research process in as much detail as possible was also geared towards ensuring credibility31. Confirmability refers to ensuring that the research findings represent the views of the participants, rather than that of the researchers32. This was done through a member checking29 focus group that was conducted to provide all the participants an opportunity to engage with the data analysis and verify the results31. Transferability was addressed through providing a detailed description of the research context29 in order for other researchers to judge whether the findings would be applicable to similar contexts or their own experiences31. In the same way, detailed descriptions of the research process ensured the availability of an audit trail for the study in order to establish dependability31.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Research Committee of the University of the Western Cape (ethics clearance registration no 14/6/54). Once ethical clearance was attained, permission to conduct the study at the hospital was obtained from the superintendent after which participants were recruited via e-mail and telephonic contact. Additionally, participants were provided with an information sheet that described the intended purpose and process of the study. They were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Formal written consent was furthermore obtained from participants. Confidentiality and anonymity was maintained by restricting access to the data to only the researchers, and by ensuring that the research report did not contain any information that would identify participants or the practice settings where the research study was conducted.

Findings

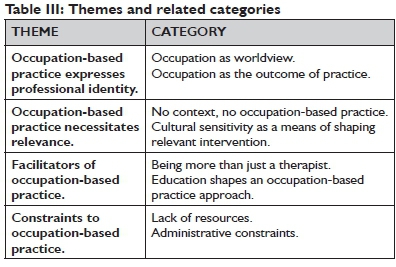

Four themes emerged from the analysis of the data: (1) occupation-based practice expresses professional identity; (2) occupation-based practice necessitates relevance; (3) facilitators of occupation-based practice and (4) constraints to occupation-based practice. These themes and their related categories are presented in Table III.

Theme 1: Occupation-based practice expresses professional identity Occupation as worldview

In articulating their understanding of occupation-based practice the participants expressed the perception that, at its core, being a member of the occupational therapy profession implied the adoption of a particular way of (professional) being. This attitude was displayed in the view that occupation is central to the profession and therefore constituted its essence or worldview. In relation to this, participants articulated various perspectives regarding living up to this worldview in every-day practice. One participant felt that it was required of occupational therapists to adopt a mind-shift that embodied their professional identity.

...occupation is our professional identity, our worldview...it's what we should be thinking and doing, it's what we should be...so your role as OT then demonstrates occupation as worldview... it's important to understand that your role becomes diversified.. .therefore OTs in this hospital think differently about their role, their practice. (Participant 4)

Another participant was of the opinion that occupational therapists are obliged to defend and protect their worldview as it embodies the uniqueness of the occupational therapy profession which is occupation-focused:

...the entire nature of our profession revolves around occupation, I think it's very important that as OTs we really guard that part of our profession... , because that's what also makes our profession meaningful. (Participant 2)

In the same spirit, concern was raised regarding 'occupation' being at the centre of the profession. Participant 1 contended that, as it currently stands, occupational therapists do not always portray this worldview, which was evident in a display of a lack of confidence in the profession.

... I feel a deep sense of value for the profession is sometimes lacking. It is important to be confident and comfortable with the profession, you know... some people don't always appreciate the profession for what it truly is. (Participant 1)

Occupation as outcome of practice

In articulating their understanding of occupation-based practice the participants stressed that its implementation is all about working towards occupation as the outcome of practice. It was their perception that a focus on occupation should be initiated from the level of assessment to inform appropriate intervention planning.

Right from the assessments... the screening form that I fill in, the - the focus is on occupation as part of assessments ... so it's right from the questions that you ask and then it guides your intervention planning as well. (Participant 1)

In their understanding of working towards occupation as an outcome of practice, the participants regarded client-centred practice an important feature of occupation-based practice. They emphasized the importance of allowing clients to verbalise their needs in order to define occupations that they find meaningful, thus directing the therapeutic process.

.asking the clients about their occupational goals and .what they would like to achieve with regards to their occupational performance. and if they are satisfied with their progress.I think that has a lot to do with client-centeredness. (Participant 2)

Community re-integration and occupational participation as practice outcomes were emphasised by the participants. They were of the opinion that a person's disability should not be considered as a limitation to re-integrate into their life tasks and roles beyond the confines of the hospital:

...regardless of their disability, or their injury that they are experiencing or that they have experienced, the outcome is community reintegration...how this person is participating in their life tasks and in their life roles once they leave this hospital. (Participant 1)

The participants employed various strategies and skills to ensure that their practice facilitates community re-integration and occupational participation. One example of such a strategy was collaboration with public and private stakeholders to ensure that some clients are re-integrated into the open labour market after completing vocational rehabilitation:

... we've been trying to collaborate with the Department of Labour and companies that do work placement... to try and set up an agreement so that we don't lose that vulnerable group, because they have the potential to be integrated into a work environment. (Participant 3)

Theme 2: Occupation-based practice necessitates relevance No context, no occupation-based practice

The participants regarded a consideration of clients' context an important feature of occupation-based practice. They viewed obtaining an occupational history of the client as essential as this enhanced their understanding of the client's context, thereby permitting relevant interventions.

. ..interventions that you offer extend far beyond participation in the confines of the hospital, so, considering: are you assessing environment, are you assessing context. are you seeing the person as an individual participating within their life tasks outside the confines of this hospital? (Participant 1)

...Yes I can do the test of eye-hand coordination by bouncing the ball because I need him to have hand function... But is that what he wants to do? Is that what he is used to? Does he have a ball at home? Did he play with a ball all the time? (Participant 4)

They explained the link between context and relevant practice and how therapy - if relevant - presents clients with opportunities to acquire skills that they will need in order to re-integrate effectively into their respective real-life contexts:

I'm not going to do an assessment or intervention that doesn't fit with what the client is showing me.or with what their needs are.You look at what the client finds important and significant and work with that. (Participant 3)

.. .it is equally important for you to translate that preparatory or therapeutic technique into something that is going to allow for occupational participation and engagement post discharge. (Participant 4)

Cultural sensitivity as a means of shaping relevant intervention

The participants' perceived the issue of culture as an important contributor to relevance and thus to occupation-based practice.

We purposefully use toys...homemade toys and culturally relevant things as well, for instance, bearing in mind how the mom plays - they'll play with the child the same way they used to play as children, it's cultural. (Participant 2)

The participants explained how culture may impact the therapist-client interaction and the manner in which interventions are implemented.

... if you are not culturally sensitive, then you disrespect your clients.... so, when doing an activity I like to ask.can we go ahead? . and I'm also mindful of the fact that not everybody regards, for example, eye contact as appropriate, so I'm mindful of those things as well... (Participant 3)

Cultural sensitivity was very important in establishing a therapeutic relationship and working towards occupational outcomes.

The appreciation of who they (patients) are as... individuals, where they come from...I think when people sense that about you, they just open up and it fosters IPRs (interpersonal relationships), influencing intervention positively... (Participant 1)

Theme 3: Facilitators of occupation-based practice

Being more than just a therapist

Personal and unique attributes ascribed to being an occupational therapist, were highlighted as factors that enriched practice for example being creative and being comfortable with engaging in diverse occupations. It was highlighted that the very same personal attributes and talents that are applicable personally also serve the same purpose professionally.

... I'm very much the same person in my private life with my family that I am as an OT. ...somebody who is empathetic- ...who has compassion... I'm also quite creative... you yourself have to engage in the occupation right.with an adult, I have to actually bake with them and with a child I have to play. (Participant 2)

Participants articulated that occupation-based practice can be facilitated by therapists paying attention to the nature of services traditionally offered opposed to emerging services that would be regarded as more non-traditional and 'out of the box'.

When you work in a setting like this, you can't think in a box ...you have to be more than just a therapist and think about the service that you need to provide... (Participant 1)

Strategies highlighted by the participants included fundrais-ing, which also involved mediation in order to increase access to resources.

.we write motivation letters to our hospital board where we get money into the department...we write donation letters and we do fundrais-ing...for the patients here at the OT department, but also for them to leave with if it's going to help them to engage in their occupations. (Participant 1)

I need to be mediating between, you know, the patient and the funder... so that they can provide access, for certain resources that will enable occupation. (Participant 2)

Another intervention strategy named was that of advocacy on behalf of clients for them to access occupational therapy services and resources both pre-and post-discharge.

... We've actually broadened our role to advocate for the patients more...to collaborate with different stakeholders, it's on an individual basis but... we try to create change on a larger scale as well by creating opportunities and resources for our patients... (Participant 3)

Advocacy initiatives involved the engagement with policy makers, as well as the analysis and monitoring of hospital policies as enablers of occupation.

...it's looking at how we can also change and advocate for policy... to enable thepatient...it's making sure that ...policies...in the department and the policies of the hospital and of the department of health are actually enablers for the patient. It's looking at how we can make the policy environment, - an enabler instead of a barrier .to enable occupation. (Participant 4)

Education shapes an occupation-based approach to practice

A key facilitator of occupation-based practice identified by the participants was that of occupational therapy education. They stressed the importance of education in facilitating graduates' understanding of occupation and related theoretical constructs.

I think the kind of theories that you learn and that occupation-focus in your education.as students we learnt all about occupation as means and occupation as end. it shaped the way that you view a client and the way that you assess and it shapes your intervention... (Participant 2)

One participant highlighted the importance of education in enabling students to ask the right contextual questions as facilitators to occupation-based practice implementation, particularly in relation to critical reasoning, as this was an important skill.

... as students we were taught the type of questions to ask... the structural, the contextual, here and of course outside where the patient comes from... your critical reasoning is important. (Participant I)

The availability of continued professional development opportunities was identified as a crucial facilitator of occupation-based practice. An in-service training opportunity, in the form of an interest group focussed on exploring occupation-based practice, was a strategy adopted by the occupational therapy department at the hospital setting to facilitate professional development.

. in terms of in-service training, we are very much mindful of occupation-based practice.we form an interest group and work through practice issues collectively... (Participant 2)

These interests groups are regarded as a platform to enable therapists to stay on par with contemporary professional developments.

....what we generally do is we try and-present...new developments within the profession, so that all of the OTs are on par, a lot of the changes that is happening in the department is based on those developments. (Participant 4)

Theme 3: Constraints to occupation-based practice

Lack of resources

All the participants identified a lack of resources such as time, funds and materials as constraints to implementing occupation-based practice. This meant that they were therefore not always able to address the diverse needs of their clients.

. but I mean there are things like resources. time, budget, physical resources, all of those things do have an impact...we don't have the luxury of time and resources......the reality also is that the turnover of patients are so high because of the pressures for beds... (Participant 3)

There is a competition for beds, and as a result, clients are discharged or referred prematurely after they have received medical or surgical intervention. So, issues such as having access to assistive devices that will allow them to participate independently at home are not addressed... (Participant 4)

A lack of human resources as evident in the shortage of occupational therapists and available posts further meant that clients' occupational needs could not be addressed comprehensively.

.we need one therapist to be available for the wards but I service fourteen different wards... meaning I'm very thinly spread, between all the different wards...I can therefore only do the minimum. (Participant 2)

Administrative constraints

With regards to constraints, the participants held the view that administrative constraints i.e. some institutional rules that restrict the implementation of occupation-based practice and as a result, minimize the potential of occupational therapy services. One such rule identified is the manner in which statistics are recorded as part of the billing system used by the hospital.

...the billing system doesn't allow us to bill for a school visit...or a work visit...or doing patient-family education. The billing system historically just allowed for billing a splint, allowed for billing a wheelchair, an individual consultation. (Participant I)

The billing system generally does not recognise occupation-based interventions. The participants were of the point of view that this makes it challenging to obtain the necessary support (resources and finances) from the Department of Health.

...we've uncovered that not everything that we as OTs are doing... are actually billable because it's not part of the requirement of the Department of Health...so part of what we need to do, is to change how. how the patients are billed and what they are billed for. (Participant 4)

DISCUSSION

This study explored occupational therapists' perceptions and experiences of occupation-based practice in a tertiary hospital setting. Generally the study highlighted that the participants perceived occupation-based practice in a positive light. This was evident in an attitude displayed by the participants that signified a high regard for people as occupational beings and an appreciation of the value that occupation hold for health and wellbeing. The participants of this study demonstrated a belief that health and wellbeing could be restored through occupation-based practice. In concurrence with the views of several authors6,2,18 the findings revealed that the participants regarded occupation-based practice as an expression of their professional identity and worldview. Accordingly, they perceived an occupation-based approach to practice as a foundation of the profession.

The findings indicate that the participants utilised occupation to enable clients to actively participate in their respective environments, thereby emphasising relevant, contextual practice and community re-integration as the outcome of practice. The main goal of occupational therapy is occupational enablement6, which according to the participants, encompasses reintegrating clients into their respective life roles and tasks. The observed correlation between their practice and occupation-based practice might be explained in the way that the participants showed an understanding that occupational engagement is influenced by contextual forces and the conditions of peoples' lives4,33,34. They therefore seemed to be of the opinion that assessment of clients' contexts, and using the information to tailor interventions according to clients' needs, was non-negotiable in occupation-based practice.

In adopting an occupation-based approach, the participants perceived their roles as diverse and transformational2. These findings are consistent with the view that in implementing occupation-based practice therapists shift between roles, use various aspects of professional competence and display flexibility in addressing their clients' needs3I. Accordingly, client-centred practiceI6 was highlighted as essential to occupation-based practice. Other attributes that the participants felt allowed them to enrich an occupation-based approach to practice was that of cultural sensitivity, thinking creatively and outside the traditional box by adopting a mind shift with regards to their roles within their service context. The participants did not only see themselves as therapists providing therapy, but as advocates, mediators, enablers; as well as policy makers, fundraisers and change agents. Through strategies like advocacy and community re-integration, the participants suggested that services should focus on the creation of opportunities to allow for all individuals regardless of disability or injury to participate fully in life.

These findings are significant as the occupational therapy profession globally has identified the need to re-evaluate occupational therapy roles and responsibilities through the adoption of occupation-based practice35,36,37. Literature furthermore supports the view that occupations are meaningful when they are personally or culturally significant38,39. By acknowledging the importance of cultural sensitivity, the participants recognised that culture has a profound influence on occupation-based practice and that occupation-based practice could therefore only be relevant and effective if practice corresponds with clients' cultural values38,39.

The participants emphasised the role that continued professional development play in keeping them up to date with regards to occupation-based practice and contemporary developments in the profession. By engaging in continued professional development through participating in in-service training and communities of practice they took responsibility for the development of their practice by engaging in reflective practice, analysing their professional development needs; and identifying and utilising opportunities to address these needs40,10 This resulted in the participants gaining a better understanding of newly formulated constructs and developments within the profession that informs the implementation of occupation-based practice.

Implications for occupational therapy education, continued professional development, practice and research

The findings of this study may be useful to inform occupational therapy education in order for curricula to address occupation-based practice as involving more than the traditional therapeutic role but broader non-traditional roles such as advocacy and policy analysis at an institutional level and beyond. Additionally, the study could inform continued professional development programmes to address the diversification of the occupational therapy role in line with the development of occupation-based practice as a foundation of practice across service areas and platforms. This study confirms the need to lobby for appropriate documentation of statistics related to occupation-based practice. There is a need for further research to be conducted to generate practice-based evidence on specific strategies to overcome constraints to the implementation of occupation-based practice within diverse practice settings.

Limitations of the study

The participants selected for this study were occupational therapists who practiced within one specific tertiary hospital in the Western Cape. Consequently, the findings of this study were specific to these participants and this research setting, thus generalisation of the findings to other practice settings may not necessarily be possible.

CONCLUSION

This study generated an understanding of how occupation-based practice is perceived and experienced in one tertiary hospital setting in the Western Cape, South Africa. Even within the context of an acute tertiary hospital, occupation-based practice was understood to be a process (means) as well as an outcome (end). It can therefore be inferred that occupation-based practice was understood by the participants as a vehicle to enact change and restore health and well-being in individuals. Hence, this study confirms that occupational therapists fundamentally view occupation-based practice as a practice that enables occupational engagement and participation. The study makes a noteworthy contribution in generating an understanding of occupation-based practice facilitators and constraints within a medical model dominated practice setting. Of further significance is the study's confirmation of the importance of occupational therapists maintaining a strong professional identity that is positioned within the construct of occupation. Consequently, this research could serve as a basis for the development of continued professional development programmes to address the diversification of the occupational therapy role with occupation-based practice at its core.

REFERENCES

1. Ward K, Mitchell J, Price P Occupation-based practice and its relationship to social and occupational participation in adults with spinal cord injury. OTJR Occupation Participation and Health. 2007; 27(4): 149-156. [ Links ]

2. Polatajko HJ, Davis JA. Advancing occupational based-practice: Interpreting the rhetoric. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 79(55): 259-260. [ Links ]

3. Townsend E, Beagan B, Kumas-Tan Z, Versnel J, Iwama M, Landry J, Stewart D, Brown J. Enabling: occupational therapy's core competency. In Townsend E, Polatajko, H. editors. Enabling occupation 11: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2007: 87-133. [ Links ]

4. Hammell KW, Iwama MK. Well-being and occupational rights: an imperative for critical occupational therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 19: 385-394. [ Links ]

5. Watson R, Fourie M. Occupation and occupational therapy. In Watson R, Swartz L. editors. Transformation through occupation. London: Whurr Publishers; 2004: 9-32. [ Links ]

6. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Occupational Therapy Definition. 2012. Available at http://www.wfot.org Accessed 25/10/16. [ Links ]

7. Chisholm D, Dolhi C, Schreiber J. Occupational therapy intervention resource manual: A guide for occupation-based practice. Clifton Park, NY: Thompson Learning, Inc.; 2004. [ Links ]

8. Galvin D, Wilding C, Whiteford G. Utopian visions dystopian realities: exploring practice and taking action to enable human rights and occupational justice in a hospital context. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58: 378-385. [ Links ]

9. Daud AZC, Judd J, Yau M, Barnett FF Issue in applying occupation-based intervention in clinical practice: a Delphi study. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2016; 222:272-282. [ Links ]

10. Wilding C. Raising awareness of hegemony in occupational therapy: the value of action research for improving practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58: 293-299. [ Links ]

11. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and Process, (2nd Ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 62(6): 625-683. [ Links ]

12. Fisher A. Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: Same, same or different? Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 20: 162-173. [ Links ]

13. Polatajko H. National perspective: The evolution of our occupational perspective; the journey from diversion through therapeutic use to enablement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001; 48(7): 590-594. [ Links ]

14. Pierce D. The issue is: What is the source of occupation's treatment power? American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998; 52: 490-491. [ Links ]

15. Wilcock A. An occupational perspective of health. 2nd edition. Thorofare, NJ: Slack incorporated; 2006. [ Links ]

16. Wilding C, Whiteford G. Occupation and occupational therapy: Knowledge paradigms and everyday practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2007; 54: 185-193. [ Links ]

17. Mahani MK, Mehraban AH, Kamali M, Parvizy S.Facilitators of implementing occupation based practice among Iranian occupational therapists: a qualitative study. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2015; 29: 307. [ Links ]

18. Estes J, Pierce DE. Pediatric therapists' perspectives on occupation-based practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 19: 17-25. [ Links ]

19. De Klerk S, Badenhorst E, Buttle A, Mohammed F & Oberem J, Occupation-Based hand Therapy in SA: Challenges and Opportunities. South African Journal of Occupational Therapt. 2016; 46(3): 10-15. [ Links ]

20. Gillen A, Greber C. Occupation-focused practice: challenges and choices. British Journal of occupational Therapy. 2014; 77(1): 39-41. [ Links ]

21. Neergaard MA, Olesen F Andersen RS,Sondergaard J.Qualitative description: the poor cousin of health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009; 9(52). [ Links ]

22. McMillan JH, Schumacher S. Research in education: evidence-based inquiry. 7th edition. Pearson: London; 2010. [ Links ]

23. Daymon C, Holloway I. Qualitative Research Methods in Public Relations and Marketing Communications. 2nd edition. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2011. [ Links ]

24. Babbie E, Mouton J. The practice of social research. South African edition. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press; 2006. [ Links ]

25. Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative methods. 3rd edition. Walnut Creek, California; Alta Mira Press; 2002. [ Links ]

26. Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative and quantitative and mixed methods approaches (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2003. [ Links ]

27. Bryman A, Cassell C. The researcher interview: a reflexive perspective. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal. 2006; 1(1): 41-55. [ Links ]

28. Braun V Clarke V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3(2): 77-101. [ Links ]

29. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991; 45(3): 214-222. [ Links ]

30. Parahoo K. Nursing research: principles, process and issues. 2nd edition. Houndsmill: Palgrave MacMillian; 2006. [ Links ]

31. Curtin M, Fossey E. Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: Guidelines for occupational Therapists. Australian Occupational therapy journal. 2007; 54: 88-94. [ Links ]

32. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information. 2004; 22: 63-75. [ Links ]

33. Watson R, Swartz L. Transformation through occupation. London: Whurr publishers; 2004. [ Links ]

34. Galheigo S. What needs to be done? Occupational therapy responsibilities and challenges regarding human rights. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58(2): 60-66. [ Links ]

35. Guidetti S, Tham K. Therapeutic strategies used by occupational therapists in self-care training: a qualitative study. Occupational Therapy International. 2002; 9(4): 257-276. [ Links ]

36. Kronenberg F Algado S, Pollard N. Occupational therapy without borders: learning from the spirit of survivors. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2005. [ Links ]

37. Kronenberg F, Pollard N, Sakellariou S. Occupational therapies without borders volume 2: towards an ecology of occupation-based practices. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2011. [ Links ]

38. Whiteford G, Wilcock A. Cultural relativism:occupation and independence reconsidered. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000; 67: 324-336. [ Links ]

39. Rudman DL, Dennhardt S. Shaping knowledge regarding occupation: examining the cultural underpinnings of the evolving concept of occupational identity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2008; 55: 153-162. [ Links ]

40. McCluskey A, Cusick A. Strategies for introducing evidence-based practice and changing clinician behaviour: a manager's toolbox. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2002; 49(2): 63-70. [ Links ]

41. Chrisholm D, DolhI C, Schreiber J. Occupational therapy intervention: a guide for occupation-based practice. Australia: Thomson Delmar Learning; 2004. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lucia Hess-April

lhess@uwc.ac.za