Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.47 no.2 Pretoria ago. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n2a9

COMMENTARY

Joining the Dots: Theoretically Connecting the Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability (VdTMoCA) with Supported Employment

Marna de BruynI; Jon WrightII

IB OT (University of Pretoria), MSc OT (University of Brighton)- MSc candidate, University of Brighton, at the time the paper was written. Employment Manager, Living Link, Johannesburg

IIDipCOT (London School of Occupational Therapy); MSc Health Psychology (City University, London); PGCE (University of Brighton); PhD (University of Brighton)- Principal Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, University of Brighton

ABSTRACT

The Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability (VdTMoCA) presents a framework for understanding client motivation and action in occupational therapy, emphasising the relationship between motivation and action. Similarly, motivation to work is regarded as the primary and in some instances, the only eligibility criterion for inclusion in supported employment services. This commentary explores the potential theoretical link between the VdTMoCA and supported employment, primarily applied to the South African context. It is aimed at occupational therapists already familiar with the VdTMoCA. The following aspects of the VdTMoCA are theoretically applied to the context of supported employment: (1) motivation and action, (2) purposeful activity and (3) the use of graded challenges. It is tentatively concluded that the VdTMoCA may be compatible for use in supported employment at lower levels of creative ability. This would require that it is used as a means enabling participation in competitive employment, as opposed to raising the threshold for those considered appropriate candidates for employment.

Key words: Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability, supported employment, motivation, action, purposeful activity

INTRODUCTION

The Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability (VdTMoCA) provides a unique occupational perspective of the relationship between motivation and action1,2. Similarly, motivation plays a central role in supported employment, when a person's motivation to work is regarded as the primary or only criterion for inclusion in such services and programmes3. Supported employment may be defined as services which enable employment in the open labour market for people with various disabilities3. Vocational support may include on-site job coaching, job analysis and matching, task or environmental adaptations, education of employers and advocacy for the employment potential of people with disabilities. A brief theoretical exploration of the link between the VdTMoCA and supported employment is presented.

Economic empowerment has been proposed as an integral part of occupational therapy practice in developing countries4. Despite progressive labour legislation, the national unemployment rate in South Africa is estimated at approximately 25%5. Unemployment statistics confirm that economic empowerment remains an appropriate priority in South African occupational therapy practice. Supported employment, as a model that enables competitive employment for people with disabilities, may assist in addressing this challenge. Although the significance and progressive development of work participation is integral to the theory and application of the VdTMoCA, the use of the VdTMoCA has only been briefly described in vocational rehabilitation6. Furthermore, its potential use in supported employment services, that could enable economic empowerment4, has not been documented.

Involvement in supported employment has been suggested as a potentially significant role for occupational therapists in mental health and appears highly compatible with occupational therapy practice7,8. While these suggestions apply to occupational therapy practice in the United Kingdom, occupational therapy practice in South Africa may increasingly include supported employment. In fact, given the national unemployment rate5, employment may be regarded as a priority area for occupational therapy practice in South Africa. This presents a unique opportunity to use the VdTMoCA to enable competitive employment for those clients who express the need to work, especially at the levels of self-presentation and passive participation. The VdTMoCA could assist occupational therapists to enable engagement in meaningful employment as opposed to raising the threshold for those who are considered 'employable' in the open labour market.

This discussion will consider the theoretical compatibility between the VdTMoCA and supported employment. It is aimed at occupational therapists already familiar with the VdTMoCA. Firstly, a brief overview of the VdTMoCA and supported employment will be presented. This will be followed by a discussion of how each of the following aspects of the VdTMoCA may apply to supported employment: (I) motivation and action, (2) purposeful activity and (3) the use of graded challenges12.

The Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability (VdTMoCA)

During the early sixties and seventies, Vona du Toit, a South African occupational therapist, developed the theory underpinning the Model of Creative Ability that identified and described six hierarchical levels of motivation with corresponding levels of ac-tion1:55-81. These levels as described in the VdTMoCA, are listed in Table I on page 50.

Creative ability "is manifested in a tangible or intangible product, which acts as evidence of the level of creative potential attained"1:22. The VdTMoCA suggests that action is governed and produced by motivation and that success or failure equally feeds into motiva-tion1:105. While research and validation of the levels of creative ability remain ongoing, the VdTMoCA enables a unique occupational perspective for understanding client motivation and action9,10 .

It is important to note that the VdTMoCA proposes the possibility of growth in a person's motivation by engagement in purposeful activity, specifically when maximal effort is successfully applied at the parameters of an individual's current level of creative ability137 & 104. A bi-directional relationship between motivation and action is assumed and is of particular importance when considering the use of the VdTMoCA in supported employment programmes. The possibility exists that a person may become increasingly motivated to work the more they participate in meaningful employment. The opposite is also true, the longer a person is unable to engage in work for various possible reasons, the lower the motivation may become to pursue and participate in employment. This may explain why 'discouraged job seekers' are recorded as a specific category within unemployment statistics5. It has not been determined how many people with disabilities are part of the 'discouraged jobseek-ers' in South Africa.

Supported Employment

Several decades ago supported, competitive employment was suggested for people with severe disabilities in North America11. There are some organisations, such as small non-profit organisations and private enterprises, offering this service in South Africa but the availability of supported employment services remains highly limited12. Theoretically, eligibility for inclusion in supported employment is based solely on a person's motivation to work3. Supported employment is emerging as a superior alternative to other vocational rehabilitation approaches that focus on therapeutic work, sheltered or protective employment outside the open labour market13,14. Supported employment facilitates the employment and integration of people with disabilities within every day employment settings. However, supported employment is not without its challenges. These include the definition of competitive employment15 and management of the variety of barriers that may prevent supported employment implementation16. Nevertheless, it may provide a viable route for occupational therapy clients seeking to enter into employment. It may allow people with disabilities access to the same economic and social benefits of the open labour market as the rest of the working population and can be implemented in a variety of work environments, executed cost-effectively and applied to various client populations17.

Connecting the VdTMoCA and Supported Employment

In the development of the theory underpinning the VdTMoCA, Vona du Toit gave much attention to a person's work capacity, when employment potential was based on a client's level of creative ability137-42. It was suggested that selected work in the open labour market is possible for clients at and above a level of passive participation1:50. This level of creative ability describes motivation that is aimed at skill acquisition and action that is orientated towards a process or product2. Given the nature of motivation and action, selected employment in the open labour market seems a reasonable assumption for this level of creative ability.

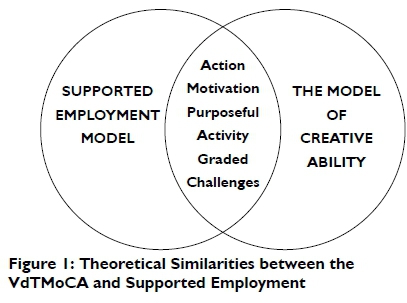

It is unclear what Vona du Toit regarded as 'selected work' in the open labour market150. Sheltered and protective employment was suggested for clients presenting at levels of creative ability lower than passive participation1:50. Sheltered and protective employment may be regarded as settings in which people with disabilities may work that are not based on open labour market principles in terms of competition, expected output and remuneration. These settings are not integrated with mainstream working society and are separated from what is considered 'normal' work spaces. They are designed specifically for the employment of people with disabilities. The predictions of employment potential outside of the open labour market for clients on the level of self-presentation are reflective of practice at that time. The question arises whether the VdTMoCA and supported employment are compatible after all? The similarities and potential links between the supported employment model and the VdTMoCA are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1 demonstrates how motivation and action, purposeful activity and graded challenges are constructs from the VdTMoCA that theoretically link to the model of supported employment. These theoretical links will be discussed in more detail.

Motivation and Action

Vona du Toit extensively described how motivation is expressed in action and suggested that 'work-ready participative action' would emerge once a person achieves a level of passive participation187. 'Work-readiness' remains a broad and somewhat ambiguous construct. However, in supported employment it has been advocated that clients who express the desire to work be taken at face value3. If a client deemed to be at a level of creative ability lower than passive participation expresses either the desire or need to work, they should be regarded as suitable candidates for inclusion in supported employment programmes.

Post-apartheid labour legislation, such as the Labour Relations Act (Act 66 of 1995)18 and Employment Equity Act (Act 55 of 1998)19, was introduced soon after 1994 in an effort to achieve a South African workforce representative of its diverse population. While legislation alone will not enable equitable employment for people with disabilities20, current legislation may create a context that is more supportive of people with disabilities working in the open labour market than was the case when the theory of creative ability was first developed. Given these recent developments, Vona du Toit's approach in predicting the employment potential of clients at various levels of creative ability may be regarded as somewhat conservative in modern day practice.

Outcome measures based on the VdTMoCA, such as the Activity Participation Outcome Measure (APOM)9, appear suitable to document and present changes in the activity participation of clients in a supported employment programme. This could provide an indication of the changes in client motivation and action that may occur in such programmes.

All eight domains of the APOM9 appear well-suited for outcome measures in a supported employment programme. Despite this, it should be noted that the APOM has not been validated in community-based settings. The use of the APOM in alternative settings, such as community-based supported employment services, would however require further research.

While Vona du Toit suggested that action is governed by motivation, she also firmly believed that motivation is influenced by engagement in purposeful activity1. Given the proposed interaction between motivation and action, a person's motivation may increase when engaged in purposeful activity whilst increased motivation will most likely lead to increased activity participation1:82. Conversely, motivation may decrease when participation in purposeful activity is limited or unsuccessful. The use of purposeful activity in supported employment programmes requires further consideration as the interrelatedness between action and motivation may be therapeutically employed to facilitate such activity.

Purposeful Activity

Vona du Toit acknowledged that 'man through the use of his body (which is himself) in purposeful activity can, and indeed must influence the state of his own physical and mental health, and spiritual well-being'12. 'Purposeful activity'1 presents an exciting challenge for occupational therapists considering the use of the VdTMoCA in supported employment services. Given the emphasis on client-centred support3, supported employment programmes would include purposeful activities to enable clients to access and retain employment. Equally, the VdTMoCA was not designed to prescribe activities but should rather be used to identify the requirements that activities should fulfil in accordance with a person's level of motivation and action2.

Participants in a qualitative study in the United Kingdom, valued appropriate job matching and having their interests recognised in supported employment programmes21. While these qualitative findings are not generalisable to larger populations, it suggests that supported employment programmes may enable participation in purposeful activity. It has been argued that creative ability directly affects and is affected by activity participation, perhaps more specifically by participation in purposeful activity in the context of a particular individual1,2. The challenge arises for occupational therapists to support the expansion and restoration of work capacity using purposeful activity. Arguably, clients may find more purpose in activities strongly related to open labour market employment, such as support with job searching, interview preparation and job applications as opposed to activities that do not have a clear focus on addressing their need for employment.

Vona du Toit suggested that 'work participation in a patient will be most effectively restored by a programme which is aimed at the development of creative ability through interrelated sequential levels'1:42. However, she rejected the notion that 'work ability can be arbitrarily superimposed at the end of a treatment programme, which has not specifically been structured as a work-related programme'1:42. Competitive employment should always be the aim of supported employment programmes3 and would, therefore, be highly compatible to du Toit's original view of what work programmes should be. It is necessary to consider how work participation may be achieved via the use of graded challenges as described in the VdTMoCA.

Graded Challenges

The use of appropriate challenges may result in the exertion of maximal effort required for an increase in creative ability1,2. Supported employment prescribes graded, individualised support for clients to access, enter and retain competitive employment3. The degrees of support required will vary in supported employment services according to the needs of individual clients. For example, one client may require more coaching when placed in an open labour market setting while another may master work tasks more easily and require less job coaching assistance. The highly inclusive nature of supported employment programmes presents a shift from du Toit's original suggestion that clients at levels below passive participation were not suitable candidates for employment in the open labour market1:50. It is important to note that many people with severe mental health problems have the need to work as demonstrated by a service-user led research project in England in 200622.

It seems highly unlikely that a person who presents at the early stages of creative ability (tone or self-differentiation)1 will express the need to work. However, it seems possible that a person at a level of self-presentation may express the need to work as part of the 'readiness to present the newly identified and basically differentiated self to people and situations'1:62. This need or desire to work may depend on a variety of factors including pre-morbid levels of functioning, previous employment history, social and cultural contexts as well as financial responsibilities and needs. While it may take extraordinary initiative, originality and careful planning from the therapist, competitive employment may be possible for such a person, provided adequate support is available. Support can range from on-site job coaching, employer education and sensitisation, off-site electronic or telephonic consultation, environmental adaptations, reorganisation of work tasks and regular follow-up contact with both the employer and the individual employed.

The VdTMoCA is a useful theoretical framework to provide supported employment services appropriate to an individual client's level of creative ability. Accordingly, a person on a level of self-presentation may well benefit from a period of job sampling. This refers to the placement of an individual in different open labour market settings doing various work tasks in order to 'sample' possible jobs. Job shadowing may be an alternative solution when job sampling is not possible, where a person 'shadows' an employee to understand a specific job and its requirements. Both job sampling and shadowing may allow for exploration of vocational interests, activities and abilities within real work situations. The occupational therapist would be able to use the principles of activity presentation and handling, as outlined in VdTMoCA1, to support such clients in their employment pursuits. Given the explorative nature of action at this level of creative ability, the potential working environment would require careful consideration and scrutiny. Suitable work environments may include entry-level jobs with high levels of supervision in structured environments such as production lines or merchandising.

While clients at this level are not norm-aware or product-orientated1, it is suggested that this does not necessarily warrant exclusion from employment, especially if a person has expressed the need to work. It seems that norm-awareness and compliance has been regarded as essential for employment potential in the open labour market1. However, it could be argued that these components may only emerge when clients are exposed to competitive employment in which performance is supported. For example, a person may only become aware of norms regarding time-keeping and personal hygiene when placed in an actual work environment where this is an explicit norm adhered to by all employees.

Overall, the grading of challenges and provision of adequate support, using the VdTMoCA as a guideline, may assist in ensuring successful supported employment for clients at various levels of creative ability.

CONCLUSION

The VdTMoCA may be used to assist clients to access and retain sustainable employment in the open labour market by facilitating the provision and grading of activities appropriate to an individual's current level of creative ability. There may, however, be several challenges with the practicality of doing this within open labour market settings. Key aspects of the VdTMoCA that appear well suited to supported employment include the notion of purposeful activity and graded challenges. However, this commentary reflects a brief theoretical exploration of the subject and further research is required to validate the use of the VdTMoCA in supported employment programmes.

Overall, it is concluded that The VdTMoCA should not be used to raise the threshold for those who are deemed suitable candidates for competitive employment. Instead, it may hold potential for occupational therapists to appropriately assist clients at different levels of creative ability, and especially at the levels of self-presentation and passive-participation, in supported employment programmes. Ultimately this would require originality, resilience and ingenuity on the part of the therapist and it remains to be seen whether occupational therapists are up to the challenge.

REFERENCES

1. Du Toit, V Patient Volition and Action in Occupational Therapy. 4th Ed. Pretoria: The Vona & Marie du Toit Foundation; 2009: 2, 22, 24-37, 50, 55-82, 87, 104-105. [ Links ]

2. de Witt, P Creative Ability: A Model for Individual and Group Occupational Therapy for Clients with Psychosocial Dysfunction, Chapter 1. In Occupational Therapy in Psychiatry and Mental Health. Edited by Crouch, R, Alers V 5th Ed. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2014: 3-23. [ Links ]

3. Bond, GR, Drake, RE, Becker, RD. Individual Placement and Support: An Evidence-Based Approach to Supported Employment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [ Links ]

4. Ramukumba, A. 'Economical occupations: The hidden key to transformation' Presented at 2014 Vona du Toit Memorial Lecture. South Africa, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYMBdt_nHv0&feature=youtu.be [Accessed: 10 November 2014]. [ Links ]

5. Statistics South Africa. Work and labour force. http://beta2.statssa.gov.za/?page_id =737&id=l [Accessed: 15 January 2015]. [ Links ]

6. Castelijn, D, de Vos, H. The Model of Creative Ability and vocational rehabilitation. Work. 2007; 29(1): 55-61. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.brighton.ac.uk/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=c0f8e34b-faad-4df4-b024-10f00315a8a3e%40sessionmgr110&vid=1&hid=110 [Accessed: 15 January 2015]. [ Links ]

7. Lloyd, C, Williams, PL. The future of occupational therapy in mental health in Ireland. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009; 72(l2): 539-542. DOI: 10.4276/030802209X12601857794772 [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

8. Priest, B, Bones, K. Occupational therapy and supported employment: is there any added value? Mental Health and Social Inclusion. 20l2; l6(4): I94-200. DOI: 10.1108/20428301211281050 [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

9. Castelijn, JMF. Development of an outcome measure for occupational therapists in mental health care settings. Doctoral dissertation. University of Pretoria; 2010. http://upetd.up.ac.za/thesis/available/etd-02102011-143303/ [Accessed 15 January 2010]. [ Links ]

10. Castelijn, D. Using measurement principles to confirm the levels of creative ability as described in the Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 44(1): 14-19. http://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/view/228/l26 [Accessed: l5 January 2015]. [ Links ]

11. Wehman, P. Supported competitive employment for people with severe disabilities. Special Education and Rehabilitation. 1987: 187-198. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/23448644?uid=2129848&uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=3&uid=5910784&uid=67&uid=2129760&uid=62&sid=21106570388863 [Accessed: 15 March 2015]. [ Links ]

12. van Niekerk, L, Coetzee, Z, Engelbrecht, M, Hajwani, Z, Land-man, S, Motimele, M, Terreblanche, S. Supported employment: Recommendations for successful implantation in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 41(3): 85-90. http://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/view/109/68 [Accessed: 16 March 2015]. [ Links ]

13. Dowler, D.L, Walls, RT. A review of supported employment services for people with disabilities: Competitive employment, earnings and service costs. Journal of Rehabilitation. 2014; 80(1): 11-21. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.brighton.ac.uk/docview/1512705219/fulltextPDF/EA9953D6CBB64352PQ/l?accountid=9727 [Accessed: 16 March 2015]. [ Links ]

14. Wehman, P, Chan, F, Ditchman, N, Kang, H. Effect of supported employment on vocational rehabilitation outcomes of transition-age youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A case control study. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2014; 52(4): 296310. DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.4.296 [Accessed: 10 March 2015] [ Links ]

15. Wilson, A. 'Real jobs', 'learning difficulties' and supported employment. Disability & Society. 2003; 18(2): 99-1 15. DOI: 10.1080/0968759032000052770 [Accessed: 22 March 2015]. [ Links ]

16. Boardman, J., & Rinaldi, M. Difficulties in implementing supported employment for people with severe mental health problems. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 203(4): 247-249. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.121962 [ Links ]

17. Kamp, M., Lynch, C. Handbook Supported Employment. Cornell University ILR School; 2007: 5-8 http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=l337&context=gladnetcollect. [ Links ]

18. Labour Relations Act. 1995. SI. 1995/66. Department of Labour. http://www.labour.gov.za/DOL/legislation/acts/labour-relations/read-online/amended-labour-relations-act [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

19. Employment Equity Act. 1998. SI. 1998/55. Department of Labour: Cape Town. http://www.labour.gov.za/DOL/downloads/legislation/acts/employment-equity/eegazette2015.pdf [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

20. Maja, PA, Mann, WM, Sing, D, Steyn, AJ, Naidoo, P Employing people with disabilities in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 41(1): 24-32. www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/download/16/22 [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

21. Johnson, RL., Floyd, M, Pilling, D, Boyce, MJ, Grove, B, Secker, J, Schneider, J, Slade, J. Service users' perceptions of the effective ingredients in supported employment. Journal of Mental Health. 2009; 18(2): 121-l28. DOI: 10.1080/09638230701879151 [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

22. South Essex Service User Research Group (SE-SURG), Secker, J. Gelling, L. Still dreaming: Service user's employment, education and training goals. Journal of Mental Health, 2006, 15(1): 103-111. DOI:10.1080/09638230500512508 [Accessed: 24 April 2015]. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Marna de Bruyn

marna.debruyn@gmail.com