Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.47 no.2 Pretoria Ago. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n2a5

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Street Play as occupation for pre-teens in Belhar, South Africa

Amanda A BrackmannI, **; Elelwani RamugondoII, *; Adrienne DanielsIII, **; Fezeka GaleniIV, **; Michael AwoodV, **; Tessa BushVI, **

IBSc Occupational therapy (UCT) Groote Schuur Hospital

IIBSc, MSc & PhD Occupational Therapy (UCT)- Associate Professor, Dept of Occupational Therapy, University of Cape Town

IIIBSc Occupational therapy (UCT)- Lentegeur Psychiatric Hospital

IVBSc Occupational therapy (UCT)- Christ the King Hospital

VBSc Occupational therapy (UCT)- Western Cape Rehabilitation Centre

VIBSc Occupational therapy (UCT)- Bradford City Council UK

ABSTRACT

Street play is often overlooked as an important activity for young people and can have negative connotations associated with it. There is currently no documented research which describes the meaning children and young people ascribe to street play. What people do every day - which may promote meaning, health and well-being - is regarded as occupation within occupational science and occupational therapy. This paper explores the experiences of pre-teens who engage in street play within the context of Belhar, South Africa. It reports on a study conducted to gain insight into street play from the perspectives of this group of young people, with the purpose of informing occupation-focussed occupational therapy with this population in contexts similar to Belhar. The findings of the study support an occupational justice approach to occupational therapy, which requires interdisciplinary research and practice, in order to inform policies such as the Open Streets initiatives that should promote children and young people's meaningful participation in society. They also challenge the traditional treatment modalities and recommend further research and discussion into rhetoric(s) such as play as power and identity.

Key words: street play; phenomenology; pre-teens; occupational justice; play space

INTRODUCTION

Street play has been overlooked as an important activity for young people and often conjures up anxieties about child safety. There is presently no documented research that describes the meaning children and young people ascribe to street play and the paucity of research with respect to children and street play was highlighted by Barron1. The research reported on in this paper explores the experiences of pre-teens who engage in street play within the context of Belhar, a low- to middle income community in Cape Town, South Africa. The study was undertaken to gain insight into street play from the perspectives of pre-teens, in order to inform occupation-focussed occupational therapy in contexts similar to Belhar.

Occupation refers to more than just paid employment or vocation within occupational therapy or occupational science, the latter being a fairly new discipline concerned with studying the form, function and meaning of human occupation2. While definitions of human occupation are vast and varied within occupational therapy and occupational science literature, it is broadly referred to as the everyday familiar activities that occupy people's resources of time, energy and personal capacities, and may have implications for health and well-being. An occupational justice approach to occupational therapy further highlights the importance of individuals, groups and communities being able to engage in occupations that matter to them, as well as bringing meaning and fostering health and well-being3,4, even when these may be valued differently across various social classes and societies.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Play through many lenses

Play, regarded in occupational therapy as the main 'business' or occupation of childhood5, is one of the most researched constructs6. Yet, play remains one of the most difficult phenomena to understand as a result of being the subject of many social constructs5. Sutton-Smith's6 analysis of the underlying rhetoric of play is perhaps the most illuminating of the way in which scholars have seen play. Play in itself, however, is inherently contradictory, reflecting "turbulence, free improvisation, and carefree gaiety" or paidia on the one hand, and "arbitrary, imperative, and purposely tedious conventions" or ludus on the other713. In studying capoeira, Wesolowski8 found this Afro-Brazilian fight/dance/game, taught to both adults and children in various settings, to display an interesting paradox of simultaneous freedom and constraint. Children's play is also often dictated to by societal and parental anxieties about the best way to raise children and nurture their development9. Play's paradoxical nature and sensitivity to context make for an interesting journey for anyone researching it.

For the most part, children's play is idealised by adults9'10,11. It is often imagined as beautiful, joyful, imaginative, daring, and filled with improvisation and carefree gaiety8,9. Moran9 regards this view of play as both concomitant with the myth of childhood innocence, and an invention of the middle and upper social classes. Berman10, however, found similar assumptions about childhood purity amongst the K'iche' Maya in Guatemala, where children are mostly regarded as too socially immature to harbour ill feelings, and to lack interest in the adult world. In the quest to preserve this presumed innocence of childhood, adults have often sought to regulate children's p|ay12,13,14,15,16. Gaunt17, for instance, suggests that the game of Double Dutcha was taken away from the streets by adults, given structure, and then returned to the girls with police supervision in order to safeguard girls' sexual innocence.

Others have been concerned about how children as players are reduced to consumers by aggressive capitalist markets which recast the 'sacred child' through his or her spending power18. Moran9also observed that through the creation of the 'nostalgia mode' cemented on the idealisation of childhood innocence, the United Kingdom managed to drive the highly commercialised heritage industry, marked by exorbitant prices for objects such as antique toys and miniature doll houses.

Other authors have also seen children's play as reflecting broader societal trends about power relations between adults and children9, or across social classes13, 19, as societies negotiate transitions within increasingly capitalist global systems19. Even as these scholars perhaps burden children's play with great social relevance and political weight, it is often trivialised by the low priority it is given by governments in their funding models15, and the disregard of children's voices in the planning required for human life in cities, towns or informal settlements.

Play: emergent of context

Children's play, like any other human engagement or occupation, cannot be separated from the context within which it occurs20. Historical circumstances together with prevailing socio-economic and political factors often influence the participation or occupational choices individuals and whole communities, including children, make21. Huge contrasts in how children occupy their time where they live can be found across geopolitical contexts with differing socio-economic resources. In much of the developed world, the home space has become the most favoured place for young people due to technology and the internet, which afford them unlimited opportunity to connect with the larger world12. Cyberspace-enabled play interactions are often part of these connections. Young people in under-developed communities, on the other hand, often have the street as the place for meaningful connections and play interactions with peers10,22,23,24.

Street as contested space: Protecting children at what cost?

A number of authors advocate for streets to be regarded as inherently playful spaces13, 15,16,25 often bemoaning the vehicle traffic domination of such space, and masking disproportionate economic and power relations which favour the economic development agenda at the expense of pedestrians and children. Those who advocate for children to be taken off the street, on the other hand, cite safety as the main reason and assume that children's needs will be met through making provisions for structured play environments or playgrounds15, often without consulting the children themselves15, 16. While traffic is often cited as the reason to contain children's play within structured environments, negative socialising agents on the street, which often include other children15, are also seen by adults as a threat. Those who advocate for children's presence on the street have, however, made the point that removing them is tantamount to denying them their contribution to building a sense of community15,16 , 26. In fact, streets have been found to be imbued with various meaning for different users27, while shared meaning has encapsulated the street as a space for power, protest and expres-sion28. Through the derive - a concerted effort to fully experience the in-between-space as one travels from one point to a destination within urban spaces - collective play becomes possible27. Viewed this way, the street offers more than playgrounds can ever do as an agent of socialisation, and a significant space where children and young people will form an identity29.

Children's play and occupational therapy

Play has been recognised in occupational therapy as a vital part of childhood30'31. In occupational therapy literature, the rhetoric(s) of "play as progress", "play as self" and "play as imaginary"6 have been fully adopted, informing a practice where play has largely been used to advance child development, learning, self-expression, and imagination19,30 Stagnitti's31 review of literature on play in occupational therapy demonstrates very clearly how the revival of interest in play within the profession at the turn of the 2lst Century under the leadership of Mary Reilly, as well as the pursuit to develop a clinically viable assessment for children's play, was driven by growing recognition that it was important for development3l. Rhetoric(s) that have been mostly ignored in occupational therapy literature are; "play as frivolity", "play as identity", "play as power" and "play as fate"6. Respectively, these rhetoric(s) advance an understanding of play as the inversion of the work ethic; associated with the establishment of communitas or a shared collective identity; an advancement of status through competitive prowess and as having to do with the unknown but anticipated, or 'magic'6.

Much has been written about how paediatric occupational therapists often address play as secondary to other non-play therapeutic goals in interventions30,32,33, with some acknowledgement that this is partly due to the constraintsb of clinical settings where the majority of these therapists are employed30, 31. It would seem unfortunate, however, that a holistic perspective on children's play in occupational therapy would be compromised by the nature of therapists' employment.

Foregrounding children's voices on play

Like all human occupations (familiar and ordinary everyday activities that occupy our resources of time, energy and personal capacities), play is understood in occupational therapy to hold subjective meaning for the individual involved34,35,36. Yet, much of the research on play, and street play specifically, has been conducted from the perspective of adults25,37, with children's voices, particularly on how they experience play, often missing. The only research the current authors were able to locate in literature that cites children's voices regarding play on the street, focussed on what children who live on the streets of Dhaka, Bangladesh, valued as important23. These children identified work and play as two of the eight assets they valued. With regards to play, the ubiquitous nature of danger on the street at times informed the games they played. Such findings suggest a need to understand play in context, and to fore-ground the voices of those for whom play is the primary occupation - children. Drawing from a perspective of occupational justice as a justice of difference, which recognises the right of individuals to engage in meaningful occupations regardless of difference, such as age and social class3, a denial of meaningful participation for children as a consequence of a partial professional discourse on play, along with restrictive social and political structures or policies, should become a concern.

Research context

Belhar is a low to middle income area situated in the Western Cape, South Africa38, with an informal settlement in its outskirts. Frantz39found that children within the Belhar community often engaged in gangsterism as a result of a lack of recreational facilities and vocational prospects. Belhar, however, has a number of community resources, which include two health centres, two libraries from which community-based projects operate, three community halls, three sports fields and an Olympic-size indoor sports complex22,40. In their study on the time-use of pre-teens in a primary school in Belhar, Antunes et al22 found little utilisation of these community resources, but prevalent active play in the streets by 12-year olds, in particular. The paucity of literature on the meaning of street play for young people, juxtaposed against the apparent prevalence of such participation in Belhar, necessitated the current research. Thus, the following question was asked: What are the experiences of pre-teens who engage in street play in the context of Belhar? The objectives of the research were to identify the reasons why pre-teens play in the street and to describe feelings and attitudes pre-teens associate with playing in the street. For the purposes of this research, street play involved outdoor structured and unstructured play on the side walk, cul-de-sac, alley-way and the road-side within the Belhar residential area.

METHODOLOGY

Descriptive phenomenology, founded on Hursselian principles41, is the detailed description of the lived experience. The main focus of descriptive phenomenology is to understand the phenomenon and lived experience from the perspective of those being studied42, thus its use and suitability to explore the experiences of pre-teens who engage in street play in Belhar.

Gaining access

The research took place through one of the primary schools that had participated in the previous research by Antunes et al22. Permission to conduct the research was granted from the University of Cape Town's Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 525/2009). Permission to access the school was gained through the Western Cape Education Department and the school principal. Both signed assent and consent forms were obtained from all participants and their parents or legal guardians before interviews took place.

Sampling

Teachers and participants were selected using criterion sampling43. Teachers who taught learners between the ages of 11- and 12 years were approached. These teachers were asked to identify potential participants that they had personally observed playing on the street or who were known to play on the streets in their community. They were also asked to select learners who were capable of sharing details regarding their play and who met the following criteria:

Were 11 - 12 years old and living in Belhar.

Engaged in street pay.

Had the ability to express and "articulate their conscious ex-periences"43, and write about them.

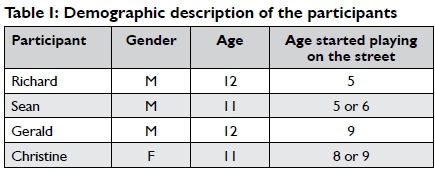

Five potential participants were identified, but one was excluded due to not meeting the criterion of area of residence. Table I presents the four participants in terms of age at the time of the research, their gender and the age at which each started playing on the street as reported by participants.

Data collection

Data were collected through three in-depth, semi-structured interviews with each individual participant (see Table II). In addition, journals were provided to the participants in order for them to document daily the forms of play they were engaged in. Areas of play identified by the participants were then photographed by the researchers after the interviews had taken place and later used in photo elicitation to draw out comments and descriptions of the locations of play from the participants. Photo elicitation is a technique that may be used within interviews as part of data collection, where photographic images are used to initiate and guide conversation or dialogue44. The in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with each of the four participants individually on the school grounds in a quiet, non-distracting and familiar environment and at a time negotiated with the teachers to ensure that no vital classwork was missed. Participants could choose to be interviewed in either English or Afrikaans by one of the researchers. Voice recorders were utilised to record the interviews, and observations were recorded later as field notes.

Participants were each seen for three interviews in total, with the average duration of each interview being 25 minutes. The first interview focussed on the broad question, 'What is it like for you to play on the street?' (See Table III for a sample of the interview questions). Participants were provided with a journal to record their experience of street play and were asked to bring these journals to the next interview as part of data triangulation. The first interview also helped identify the most common location of play on the street for each participant. The five undergraduate researchers then took photographs of these locations to use as part of photo elicitation during the second interview, which occurred the next day. The short interval between the first and second interviews was planned in order to sustain the children's focus and interest. None of the participants, however, remembered to bring the journal to the second interview. The third interview, which took place two weeks later, was conducted to discuss the contents of the journals, to perform member checking and involved the clarification of emerging themes with the participants. No new information was identified in the journals.

Data analysis

Each interview was transcribed verbatim by the undergraduate researchers, in the original language of the participant. Interviews conducted in Afrikaans were translated into English and back translated before analysis. QSR-NVivo 7 was used to analyse the data, allowing for electronic management, sorting and organisation of data into meaningful units, enabling the grouping of meaning and coded segments into themes. All descriptions from interview transcripts, participant journal entries and field notes were read in their entirety to obtain a "sense of overall data"43 before meaning segments were identified. This was done in accordance with Hycner's45 approach of immersion and reflective engagement towards phenomenologi-cal reduction. Analysis was inductive, allowing themes to emerge directly from the data rather than imposing pre-existent concepts or theories. This is consistent with descriptive phenomenology. Different methods of data collection were utilised in order to ensure data triangulation which contributes to the credibility of findings46.

Trustworthiness

A number of techniques were used to ensure trustworthiness within this study. Trustworthiness includes credibility, reflexivity, transfer-ability, dependability and confirmability47. To ensure reflexivity, the researchers made a conscious effort to acknowledge and analyse their preconceptions, biases and beliefs about the phenomenon through bracketing their assumptions as much as possible47 from the beginning and throughout the research process. The research was undertaken as part of the final year occupational therapy degree qualification and the researchers were four young adults from contexts different from those of the participants. Bracketed assumptions included statements such as; 'playing in the street is dangerous'; 'it promotes rebellious behaviour'; 'it is irresponsible'. Peer debriefing with an impartial expert researcher with experience in qualitative methods47 and member-checking took place in order to ensure credibility and confirmability. An audit trail, which was developed, maintained and reviewed throughout the study ensured confirmability and dependability as the researchers could trace the themes back to the coded segments of meaning. Member-checking allowed the researchers to verify their interpretations of the data with the participants and thick description was used to describe the context to allow for transferability of the findings.

RESULTS

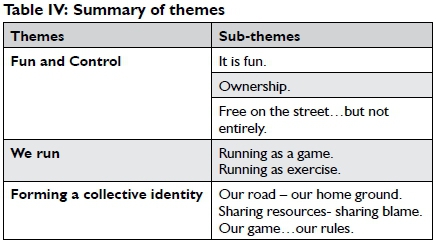

Although four themes were identified in this research, for the purposes of this article, 'fun and control', 'we run' and 'forming a collective identity', will be the focus (see Table IV).The fourth theme, 'living in a dangerous world', suggested parallels between playing on the street and the reality of living in Belhar.

Playing on the street was described as fun. This was highlighted by all participants, captured mostly through the use of an Afrikaans word 'lekker'.

Christinec: "It's 'lekker' for me; it's fun to play on the street"

Gerald: "lekker, fun, then it keeps you busy in the day and nothing bad to get up to."

Richard: "outside is more fun"

And

Gerald: "We played lekker in the street and meet more friends."

The English word 'fun' does not capture the essence of 'lekker' sufficiently. In Afrikaans, 'lekker' can be used to express various meanings; such as 'nice', lovely', and 'delicious'. The street afforded them the opportunity to stay out of trouble and make friends. So 'lekker' was it to play on the street that Christine was often willing to miss her favourite television programme in order to join others on the street.

Ownership of the street as play space came through strongly in the findings, with participants claiming territory over other competing interests, especially older youth and whenever their play was threatened by gang rivalry. This is evident in what Richard had to say when he and his friends felt pressured to play elsewhere due to rivalry between two gangs in the area:

Richard: "But it's not their road, so they can't force us now, we can play wherever we want to."

Other participants also emphasised their ownership of the street as play space.

Sean: "my play place",

Richard: "they come to our road'

And

Richard: "Yes, this is like our home ground (smiling)"

Yet, this ownership of the street and freedom to play as they pleased was often threatened. Participants spoke of how older youth would often disrupt their play by joining them and then creating new rules to make the game more difficult, or did not comply with the original rules. Adults also seemed very aware of the value playing on the street carried for these participants, and could exercise control over the child at home by threatening to take away this privilege, as evident in what Richard shared:

Richard: "...then my mother 'skell' (reprimands) me and then my mother says 'no you can't play anymore, no you [are] grounded for a week' ".

The participants revealed the idea of the street being free, an area where they were able to make their own choices, decisions, and choose their own games. This was done outside the influence and boundaries set up by authority figures, such as their parents, teachers, and other family members. But when it came to playing in the street, the participants perceived themselves as having the control, as opposed to playing in a facility where what they play or who they play with may be decided by an adult. Richard introduced the concept of control by mentioning that on the street he was free to do what he wanted to do:

Richard: "You can play anything that you want to, by doing it yourself not by the control of the play station".

He would choose to play further out of the control of his parents in order for his play not to be disturbed.

Richard: "...most of the time I play in the other road, because I don't want to play here, because every time I play here, then my mommy call [sic] me to go buy, get that and that, and they disturb me every time."

This powerful quote demonstrates how Richard chose to play in the street despite the presence of gangsters and the risk to himself.

Richard: "When I want to come play, if my friends is there, and if my friends is not there, then I not going to come out when they (the gangsters) are in the road. When they are gone, then I am coming out. But if my friends are there, then I am going to come out."

We run

Running emerged as central in the participants' experience on the street, enhancing the fun element in their play activities. Running was often part of the games played, as Christine noted:

Christine: "We knock on the peoples doors and then we run away"

Or as part of Sean and Richard's description of the Three Sticksd game:

Sean: "It has things like running and you get tired"

Richard: "You run, you run to reach over the sticks"

Running however also stood apart as a distinct form of engagement on the street.

Sean: "If you run and there... and there's a bunch of people and if you can laugh'

Participants also mentioned how running on the street was a form of exercise for them. In reference to describing why he liked playing on the street, Gerald remarked;

Gerald: "You can run some more"

Running as a form of exercise was best captured by Richard's comments, where he was quite specific about the physical benefits he derived:

Richard: "If you run, that, it's almost like exercise and that, and if you practice, that make [sic] you fit, your body.it get [sic] fit and that"

Forming a collective identity

This theme describes how the street as threatened play space cultivated shared meaning, agency and identity amongst the participants. In claiming territory over the street as play space, participants often referred to collective ownership, denoted by use of the possessive pronoun 'our'.

Richard: "They come to our road"

and

Richard: "Yes, this is like our home ground (smiling)"

This shared ownership develops over time, with participants seeming to carry an extended memory of playing on the street. It was interesting that even for Gerald, who had reported elsewhere that he played on the street from the age of nine, this memory stretched as far back as he could remember:

Gerald: "I [have] always played on the street"

Richard and Sean had reported that they started playing on the street from the age of five or six. If this is indeed true, Richard would effectively have played on the street for seven years. Solid friendships are bound to be formed over such a long span of time engaging in play together. Participants indeed referred to very strong friendships, and collective agency was demonstrated in pulling resources together for play materials, as reflected in the following quote from Richard:

Richard: "All my friends, we put money together and we buy the ball"

Participants also worked together as a team to collect available resources on the street and to come up with innovative ideas and games.

Richard: "We use, we use like stones, to make the poles for the soccer. Sticks, for the Three Sticks.for the game. "

Participants did not only share resources, but also responsibility, even when play on the street led to damage to property at times. This is indicated in a quote from Sean:

Sean: "People don't find out and they can't blame just one of us as everyone played together."

While the group carried collective blame, the individual who may have caused the damage by kicking a ball through a window for instance, is protected.

Emergent collective or shared identity was most pronounced when participants spoke about how one became 'one of them'. This was often in reference to younger children who wanted to join them, and did so through learning the participants' games and rules. Richard spoke very clearly about how this happened, illustrating how a newcomer had a designated spot from which to watch and learn before he or she could join.

Richard: "...there is a spot to sit, then they sit there, and they watch us how we play, then afterwards they ask, "can I play with" then they know how to play the game"

Study limitations

This study formed part of an undergraduate group research project and was thus subject to limitations of time and experience. The limited time would have compromised prolonged exposure for the researchers, and possibly not allowed adequate time for the participants to establish the trust necessary to share information more truthfully. As member checking allowed the researchers to take information back to the participants for confirmation, additional time may have been an ideal rather than essential. It may be argued that less immersion into the school setting, where playing on the street may be frowned upon by the teachers, along with the fact that the researchers were young adults, increased the potential for participants to feel less judged for playing on the street. Data triangulation was attempted; however, monitoring and reminders were required in order to ensure the successful use of journaling with this pre-teen age group.

DISCUSSION

Street play and the paradox of freedom and constraint: A shared struggle

The element of control as part of Belhar pre-teens' meaning-making in street play comes through very strongly in the findings of this research. The theme, 'Fun and Control', suggests an inextricable link between fun and control, where one depends on the other. Participants report on street play being fun or 'lekker' in a manner that it becomes clear that denial of this engagement would suggest great injustice. Yet, the fact that street play is dependent on resources that are not readily available, and that it is constantly under threat from older children and adults, appears to intensify the fun. This description of street play as ultimately a paradox of simultaneous freedom and constraint fits with how Wesolowski8 described capoeira, and may under-score the essence of street play.

Occupational therapists, along with many other scholars of play, have highlighted 'intrinsic motivation' and 'free choice' as two amongst various key features of play30,31,48. Intrinsic motivation suggests that children engage in play for its sake, and not to be rewarded through factors unrelated to the play experience itself49, while free choice suggests that the child is in control of when and how she or he will play. While there are clear similarities between the notion of intrinsic motivation and fun or lekker as described by participants in the current study, 'free choice' does not seem to capture the element of control as experienced in this research. 'Control' or freedom in the present study is imbued with a clear dynamic tension between claiming or enjoying it, and constraint. In addition, while on one hand 'control' in the current study depicts the individual pre-teen's ability to join others in street play at will, it seems to also suggest participants' shared or collective sense of freedom from older children and adults to play as, when and where they wish. 'Free choice' as framed in occupational therapy literature emphasises individual freedom and is silent on the collective dimension, which has clearly emerged in the present study.

The street offers opportunity for physical activity

The second theme from the current research supports ethnographic work done by Barron1 on the extent of physical activity play among children in local housing estates in Ireland, where she found that a quarter of the images children collected of their physically active play engagements were in the streets and cul-de-sacs of the housing estates. Similarly in the research reported here, the street offered a great opportunity for physical activity play. Given the environmental limitations of the terrain on the streets of Belhar where there are few trees or any other vegetation, physically active play was mostly limited to running.

Protecting children on whose behalf?

Children's play has largely been dictated by adults, stemming mainly from societal and parental anxieties about the best way to raise children, protecting them and ensuring they develop into productive and fulfilled adults9. For many adults, allowing children to play on the street is the antithesis to good parenting, and has led to many Progressive-era initiatives to build playgrounds and establish recreational programmes13,15,16. In containing children within structured play environments, 'dangers' that are cited not only include traffic, but other children as undesirable socialising agents15. Given these 'known' dangers that are often cited by adults, it is an interesting irony that children themselves may find street play as one way to stay out of trouble, as cited by one participant in the present study.

In reviewing the work of women's clubs in St Louis and Chicago between 1883 and 1994, where they contributed immensely to neighbourhood urban planning and brought about many public parks and playgrounds, Belanger13 found that these women, like many Progressive-era reformers, sought to impose their own middle-class notions about the dangers of unsupervised street play onto their working-class subjects. This view may very well be well-founded, however judging by findings from the current research, where un-supervised street play in Belhar is seemingly sanctioned by adults, who understand it to be such a privilege that controlling access to it at times served as reward or punishment to mould child behaviour.

Collective identity and occupational trajectories in context

The third theme, 'Forming a collective identity', signifies how, through street play, these pre-teens in Belhar cultivate a shared meaning, agency and identity over time. Together they come to claim territory over the street as contested space, sharing responsibility over resources for play, and accountability when something goes wrong. Each individual, by virtue of belonging to the group, is protected, having earned their place by learning and sticking to the rules of the game. While middle-class ideas about unstructured or unsupervised street play being inherently dangerous13 should not be adopted at face value, the fact that street play serves as a strong socialising agent comes through undisputedly. This was indeed suggested by Abu-Ghazzeh29, who claimed that the street offered more than playgrounds could ever do, and is a significant space where children and young people will form an identity. Street play viewed this way may advance the rhetoric of play as identity6.

It is indeed this socialising effect on children and young people that makes certain adults uncomfortable about street play, with Hart15 positing that policies for play and recreation in cities like New York came about not only out of 'fear for' children, but also 'fear of' children. Looking closely at the third theme in parallel to the context of Belhar where gangsterism is rife, such fear may be warranted. Claiming territory as a group over contested space, acting in solidarity to avoid any single member being blamed for destructive acts and inducting new members through rules before they can join games, all mirror the essence, acts and processes that are often part of gang membership50,51. It is likely that some children, who grew up playing on the street in this context, just like Richard, Sean, Gerald and Christine, mature to become gang members as part of their occupational trajectories.

Street play has reportedly diminished substantially or disappeared entirely in Western contexts and has been replaced by 'hanging out' in shopping malls and cyberspace-enabled play inter-actions12. Central to hanging out at shopping malls and internet-based interactions for these young people is the opportunity for meaningful connections with peers. In contexts such as Belhar, and for participants in the current study in particular, the street appears to be the site for such meaningful connections to come about. It appears as if sport and recreational facilities do not seem to allow the same connections and experience of fun, control and freedom as preteens experience on the street. This may suggest that our interpretation of appropriate play spaces may not equate to avenues where these preteens can experience meaningful connections. Denying these pre-teens this opportunity to play in their chosen street space without providing them with alternative spaces for similar connections may suggest a form of occupational injustice. Initiatives such as Open Streets Cape Town52, a citizen-driven initiative which promotes the reclaiming of street spaces and changing the ways in which they are used and perceived, may be one approach to moving towards this reality52.

It is also probable that the essence, acts and processes in street play that mimic gang membership, as evidenced through the second theme, may very well be found in non-violent contexts worldwide without suggesting possible grooming for gang membership as part of children's later occupational trajectories. As suggested by Galvaan21, human occupations cannot be separated from context. For street play to be safe in Belhar, and for it not to signal potential gang membership later in life, the whole community of Belhar will need to enjoy safety, and be rid of gangsterism. It is unlikely that children playing on the street alone breeds gangsterism in Belhar, but instead, the fact that this community has never enjoyed favourable socio-economic conditions38,39 and that the broader political context historically and currently sustains gang activity40. By playing on the streets, and through this forming a collective identity characterised by shared meaning and agency, these pre-teens in Belhar are contributing to building a sense of communityl5,l6,26 that must be understood in context.

CONCLUSION

This study described the experience of street play for pre-teens in Belhar, Cape Town, South Africa. The study found that street play provided significant meaning for the participants, highlighting the discursive nature of fun and control - demonstrated through the paradox of freedom and constraint. The element of 'free choice' in play was reframed, revealing a collective dimension. Running offered by games on the street as well as a play engagement in itself emerged as an important opportunity for physical activity play. Additionally, forming a collective - signified through emergent shared meaning, agency and identity - may mirror young people's participation in pursuit of meaningful connections in Western contexts. Occupational therapy intervention should be more connected to context and perhaps the therapy room should become the street. Drawing from a perspective of occupational justice as a justice of difference recognises the right of individuals to engage in meaningful occupations regardless of difference. A denial of meaningful participation for pre-teens demonstrated in restrictive social and political structures or policies, as a consequence of a partial professional discourse on play by historically focussing on rhetoric(s) such as play as progress should be a concern. Play as power and identity have been neglected and renewed interest and research into these rhetoric(s) will enhance occupational therapy practice30.

These findings support an occupational justice approach to occupational therapy, which should be strengthened through interdisciplinary research and practice, to inform policy that promotes young people's participation in the world.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Interdisciplinary research into initiatives such as Open Streets Cape Town and their impact on street play52. This should inform occupation-based practice, which challenges the traditional treatment modalities. Further research and discussion into rhetoric(s) such as play as power and identity30 should be embraced.

REFERENCES

1. Barron C. Physical activity play in local housing estates and child wellness in Ireland. Int. J. Play, Ther. 20l3; 2(3): 220-236. [ Links ]

2. Yerxa EJ. An Introduction to Occupational Science, A Foundation for Occupational Therapy in the 2lst Century. Occup. Ther. HealthCare. 1990; 6(4): 1-17. [ Links ]

3. Nilsson I, Townsend E. Occupational justice-bridging theory and practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010; 17(1): 57-63. [ Links ]

4. Townsend A, Wilcock AA. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: A dialogue in progress. Can J Occup Ther. 2004; 71(2): 77-87. [ Links ]

5. Alessandrini NA . Play - A child's world. Am J Occup Ther. 1949; 3: 9-12. [ Links ]

6. Sutton-Smith B. The ambiguity of play. London: Harvard University Press; 1997. [ Links ]

7. Barash M . Man, play, and games. Urbana: University of Illinois Press; 2001. [ Links ]

8. Wesolowski K. Professionalizing capoeira: The Politics of play in twenty-first-century Brazil. Lat Am Perspect. 2012; 39(2): 82-92. [ Links ]

9. Moran J. Childhood and nostalgia in contemporary culture. Euro. J. Cult. Stud. 2002; 5(2): 155-173. [ Links ]

10. Berman E. The irony of immaturity: K'iche' children as mediators and buffers in adult social interactions. Childhood. 2011;18(2): 274-288. [ Links ]

11. Theron L, Cameron CA, Didkowsky N, Lau C, Liebenberg L, Ungar M. A ''Day in the lives'' of four resilient youths: Cultural roots of resilience. Youth Soc. 2011; 43(3): 799-8l8. [ Links ]

12. Abbott-Chapman J, RobertsonM . Adolescents' favourite places: Redefining the boundaries between private and public space and culture. Space Cult. 2009; 12(4): 419-434. [ Links ]

13. Belanger E. The neighbourhood ideal: Local planning practices in progressive-era women's clubs. J Plan Hist. 2009; 8(2): 87-110. [ Links ]

14. Cole CL. Nicole Franklin's Double Dutch. J Sport Soc Issues. 2006; 30(2): 119-121. [ Links ]

15. Hart R. Containing children: some lessons on planning for play from New York City. Environ Urban. 2002; 14(2): 135-148. [ Links ]

16. Tranter PJ, Doyle JW . Reclaiming the residential street as play space. Int. J. Play. Ther. 1996; 4: 91-97. [ Links ]

17. Gaunt K. The games Black girls play: Learning the ropes from double-dutch to hip-hop. New York: New York University Press; 2006. [ Links ]

18. Langer B. Commodified Enchantment: Children and Consumer Capitalism. Thll. 2002; 69(1): 67-81. [ Links ]

19. Ramugondo EL. Intergenerational play within family: The case for occupational consciousness. J Occup Sci. 2012; 19(4): 326-340. [ Links ]

20. Njelesani J, Sedgwick A, Davis JA, PolatajkoHJ. The influence of context: A naturalistic study of Ugandan children's doings in outdoor spaces. Occup Ther Int. 2011; 18(3): 124-132. [ Links ]

21. Galvaan R. Occupational choice: The significance of socio-economic and political factors. In: Whiteford G, Hocking C, editors. Occupational Science: Society, Inclusion, Participation. lst ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2012:152-162. [ Links ]

22. Antunes J, Leslie C, McInnes A, Powell S . An occupational profile of preteens in Belhar, Cape Town. Unpublished undergraduate thesis. University of Cape Town, Cape Town; 2009. [ Links ]

23. Conticini A . Urban livelihoods from children's perspectives: protecting and promoting assets on the streets of Dhaka. Environ Urban. 2005; 17(2): 69-81. [ Links ]

24. Nyaumwe LJ, Mkabela Q . Revisiting the traditional African cultural framework of ubuntuism: A theoretical perspective. Indilinga-African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems. 2007; 6(2): 152-163. http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/linga/linga_v6_n2_a7.pdf (accessed 30 December 2014). [ Links ]

25. de Souza e Silva A, Sutko DM. Playing life and living play: How hybrid reality games reframe space, play, and the ordinary. Crit. Stud. Media Comm. 2008; 25(5): 447-465. [ Links ]

26. Satler G. Some observations on design and interaction on a city street. City and Society. 1990; 4(1): 20-43. [ Links ]

27. Aldred R, Jungnickel K . Constructing mobile places between 'Leisure' and 'Transport': A case study of two group cycle rides. Sociology. 2012; 46(3): 523-539. [ Links ]

28. Martin NP, Storr VH. Bay Street as contested space. Space Cult. 2012; l5(4): 283-297. [ Links ]

29. Abu-Ghazzeh T M . Children's use of the street as a playground in Abu-Nuseir, Jordan. Environ Behav.1998; 30(6): 799-831. [ Links ]

30. Parham LD. Play and occupational therapy. In: Parham LD, Fazio LS editors. Play in Occupational Therapy for children. 2nd ed. St. Louis: MO: Mosby; 2008: 3-42. [ Links ]

31. Stagnitti K. Understanding play: The implications for play assessment. Aust Occup Ther J. 2004; 51(1): 3-12. [ Links ]

32. Rodger S, Ziviani J. Play-based occupational therapy. Int J DisabilI Dev Ed. 1999; 46(3): 337-365. http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=3e816606-3bl4-44c0-b2ab-93 1 d3d4270cf%40sessionmgrl14&hid=108 (accessed 30 December 2014). [ Links ]

33. Stagnitti K, Unsworth C, Rodger S. Development of an assessment to identify play behaviours that discriminate between the play of typical pre-schoolers and preschoolers with pre-academic problems. Can J Occup Ther. 2000; 67(5): 291-303. [ Links ]

34. Pierce D. Untangling occupation and activity. Am J Occup Ther. 2001; 55(2): 138-146. [ Links ]

35. Nelson D L. Occupation: form and performance. Am J Occup Ther. 1988; 42(l0): 633-641. [ Links ]

36. Nelson DL. Therapeutic occupation: A definition. Am J Occup Ther. 1996; 50(1): 775-782. [ Links ]

37. de Souza e Silva A, Hjorth L . Playful urban spaces: A historical approach to mobile games. S&G, 2009; 40(5): 602-625. [ Links ]

38. Setplan. Southern service area spatial development framework Volume l. Tygerberg: Setplan. Report number: l248/Rl, 1999. [ Links ]

39. Frantz J . Physical inactivity among high school learners in Belhar. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Physiotherapy Department. University of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Afric. 2005. [ Links ]

40. Cloete A . Things were better then. An ethnographic study of the violence of everyday life and the remembrance of older people in the community of Belhar. Unpublished master's thesis. University of the Western Cape, Cape Town; 2005. [ Links ]

41. Van Manen M. Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany: NY: State University of New York Press; 1990. [ Links ]

42. McConnell-Henry T, Chapman Y Francis K. Husserl and Heidegger: Exploring the disparity. Int J Nurs Pract. 2009; 15(1): 7-15. [ Links ]

43. Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [ Links ]

44. Prosser J. Image based research: A sourcebook for qualitative researchers. London: Routledge Falmer; 1998. [ Links ]

45. Hycner RH. Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Hum Stud. 1985; 8(3): 279-303. http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=506be263-9aaf-4ff0-a0eb-e 168c0ecbcfl%40sessionmgr4003&hid=4214 (accessed 30 December 2014). [ Links ]

46. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991; 45(3): 214-221 [ Links ]

47. Connelly LM. What is phenomenology?. MEDSURG Nursing, 2010; 19(2): 127-128. [ Links ]

48. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991; 45(3): 214-221. [ Links ]

49. Skard G, Bundy AC. Test of playfulness. In: Fazio LS, Parham LD editors. Play in Occupational Therapy for children. 2nd ed. St. Louis: MO: Mosby; 2008: 71-93. [ Links ]

50. Rubin KH, Fein GG,Vandenberg B. e.g. The war is over. In: Mussen PH, Hetherington EM editors. Handbook of child psychology (4): Socialization, personality, and social development . 4th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1983; 693-774. [ Links ]

51. Gordon R, Lahey BB, Hawai E, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Antisocial behavior and youth gang membership: Selection and socialization. Criminology. 2004; 42(1): 55-87. [ Links ]

52. Vigil JD. Group processes and street identity: Adolescent Chicano gang members. Etho. 1988; 16(4): 421-445. [ Links ]

53. Open streets Cape Town [Internet]. About open streets Cape Town. Up to date; [Updated 2017 January; cited 2017 January 23]. Available from: http://openstreets.org.za/. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Amanda A Brackmann

amandaabrackmann@gmail.com

* University supervisor at the time the study was conducted

** Students at the University of Cape Town at the time the study was conducted

a A game in which skipping ropes are held in double and turned in opposite directions as one or more players jump in the middle in time with a song.

b For Example: high patient loads, time constraints etc.

c Pseudonyms have been used.

d Three Sticks is a game involving three sticks that are placed down on the street as close to each other as possible. Children then form a line to jump over all or one stick at a time. The last person to jump adjusts the distance between sticks using their bare-footed heel, making it harder to jump over the sticks or between them. Those who touch a stick are eliminated.