Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.47 n.1 Pretoria Apr. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol47n1a5

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Street vending in South Africa: An entrepreneurial occupation

Fadia GamieldienI; Lana van NiekerkII

IBSc OT (UCT), MSc OT (UCT)-Senior Educator, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation University of Cape Town

IIBSc OT (UOFS); MSc OT (UOFS); PhD OT (UCT)- Head of Department, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Interdisciplinary Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Not all occupations are undertaken entirely by choice. Numerous personal, cultural, economic and social factors influence participation in occupation. In low and middle-income countries, such as South Africa, disparate socio-economic factors might necessitate participation in occupations considered to be 'less desirable'. In this article the occupation of street vending is explored and discussed, with an emphasis on livelihood creation and the meaning and purpose derived from this occupation. Street vending is considered for its potential as a vocational occupation for people facing disabling conditions.

METHODS: A collective case study was done comprising six participants who were selected through maximum variation sampling. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and participant observation. Data analysis took the form of an inductive content analysis.

RESULTS: Occupational therapists need a comprehensive understanding of occupations before making judgements about these, especially when such occupations are not considered mainstream. One such occupation, namely street vending, predominates in the informal economy of South Africa. Findings revealed that, despite hardships associated with this occupation, street vendors adapt to social, political and economic challenges in their context.

RECOMMENDATIONS: A comprehensive approach is needed when appraising the suitability of occupations; one that focuses on the transformative value of occupations in livelihood creation, rather than focusing narrowly on their therapeutic use or potential to contribute to personal meaning. Occupational therapists should adopt a multi-dimensional approach by considering vocational occupations within their social, cultural and political context, whilst keeping the functional requirement in mind and matching these dimensions with impairment or disability if prevalent.

Key words: Street vending; livelihood creation; informal economy; occupation; occupational justice

INTRODUCTION

Levi, a street vendor, has been selling fruit and vegetables across from the first author's house for ten years. He offers good prices, service and goods. His stall, located along the busy road, is also used as an informal taxi pick up point. Some commuters place their orders prior to taking the taxi to work in the morning and collect it on their return home. The hawker employs three people to assist him when the need arises. All three employees were previously unemployed; one has a mental illness, one has an intellectual disability and one was previously homeless. Their tasks range from setting up the trading space, assisting with offloading goods, delivering to nearby homes and keeping Levi company during the day.

The community initially blamed Levi for contributing to crime, litter, loitering and uncleanliness in the area. This despite the fact that his stall is on the kerb and he removes all traces of trading on a daily basis. The community's view has subsequently changed because of the reliable, convenient and competitive service they receive from him.

Nevin1 suggests that it is in our best interest to consider street vendors as entrepreneurs in need of society's support, because of the informal economy's contribution to the country's revenue. However, he calls for closer cooperation between street vendors and prescribed commerce, so as to better understand the "mystical workings of pavement economies" (p.42). In this paper, research undertaken to explore 'street vending' as a livelihood creation occupation will be presented. South Africa is a low and middle income (LMIC) country with high unemployment rates that results in restricted opportunities for work in the formal sector2-4. Moreover, a large number of working-age South Africans have a low education level5, an enduring feature of the legacy of apartheid. It is against this backdrop that a particular form of street vending, also known as 'hawking', will be explored. The terms hawking and hawkers will be used in this article as it is the colloquial term for street vendors and familiar to all South Africans. In South Africa, discernible behavioural patterns, that include idiosyncratic styles of relating to customers, have evolved to provide a regional character to street vending. These signal the social and cultural embedded-ness of this occupation. It is important to note that hawkers tend to share similar social class dimensions and face particular contextual realities that could differ in other countries.

Due to limited opportunities in the formal sector of the South African economy, people are forced to become hawkers in order to generate and income. Whilst the regulatory environment has been made more conducive,3,6 very little infrastructure is available to hawkers. Without infrastructure hawkers have to re-create a place to conduct business daily, a burdensome routine. Although some hawkers are forced into the occupation by necessity or desperation, many acknowledge that it provides well for essential requirements, including shelter, food, education, and, in the case of immigrants, passage to visit their home countries.

The research into street vending recognised occupational therapy assumptions on: the benefits of work (including therapeutic value); the negative impact of unemployment on health and wellness; the influence of work environment on performance and the importance of work as a source of income.

The aim of the study was to explore street vending within the informal economy as an addition to formal work opportunities. The intention was to develop better insight into street vending and thus equip occupational therapists in their endeavours to inform policy and practice initiatives focussed on livelihood creation. Such initiatives are often intended for persons with disability or when occupational risk factors prevail.

The National Planning Commission of South Africa7 has identified under- and unemployment, as well as the poor quality of education available to learners, as two of the country's most pressing issues. It is thus important to consider a broad approach that will involve all sectors involved in offering employment opportunities (e.g. education, social development, labour, trade and industry).

Street vending has been around for centuries all over the world. The informal sector of Africa's economy, often ignored by government statisticians, is vibrant and busy11. Street vending contributes 7% to the national gross domestic product (GDP) in South Africa and generates 22% of the total employment in the country3. According to Nevin1 South African informal traders generate ZAR 32bn annually. As such street vending provides a means of employment for many people who do not operate in the formal sector of the economy for a number of reasons, which include low education level, high levels of unemployment and immigration policies. The informal economy (also known as the second economy) has been an important source of employment and the contribution of hawkers to job creation and economic growth1, as 'street savvy' business people, has largely been overlooked. In South African cities, street vendors have a strong presence at taxi ranks1, sport stadiums and railway stations. They opportunistically occupy available space surrounding shopping malls, in residential areas and at busy intersections2.

It is important to understand the history and context of hawking in South Africa, as well as the factors that have influenced its survival and popularity. Some argue that informal trading has been in South Africa for centuries. Historians and archaeologists locate the establishment of trade between South Africa and the outside world as early as AD700, as well as with the establishment of the Kingdom of Mapungubwe (1075-1220) located in the northern border of South Africa which joins Zimbabwe and Botswana. Subsequent inter-ethnic trade alliances focused on controlling the exportation of gold, copper, and ivory across the Limpopo River8. Evidence of informal trade amongst the Indian population exists since I860. Indians were employed as labourers on five year contracts and when these expired they had to choose between re-indenture, working outside of South Africa, elsewhere or returning to India9,10. Many remained in the former Natal as peddlers or shopkeepers, because these occupations required little capital or expertise, thus allowing for self-employment and an experience of freedom9. These experiences show that the occupation of hawking has been central to the lives of South Africans for a long time.

During the apartheid era, the South African government tried to stop trading activity. Traders resorted to trading portable goods and conducting business from unobtrusive spaces to avoid conflict with the law. Although many campaigns were launched between the I950's and I980's to rid cities of street vendors, informal trading persisted11. Subsequent to this, the Business Act of 1991 allowed hawkers to trade freely, without licenses, which led to a rapid increase in the number of street vendors. The lifting of restrictions on hawking coincided with retrenchment of many workers in the formal economy, thus leading to a massive growth in street trade activity. Many "survivalist traders" resorted to trading out of desperation rather than choiceII. Around I997 South Africa faced an economic crisis where large corporations and retailers were retrenching, downsizing, downscaling and closing down. Amidst this, small business owners, entrepreneurs and street vendors in the informal sector continued to contribute to the greater economy10,12. Subsequently there was a growing recognition of the potential role that street vending can play in terms of job creation and poverty alleviation13-16.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A review of occupational therapy and occupational science literature yielded very little research on street vending in terms of the purpose, meaning and characteristics of this occupation. Furthermore, limited attention had been given to the "lived-experience" of street vendors. Research tended to focus on the entrepreneurship, economic or business factors related to street vending but without exploring street vending in terms of the of inherent properties and demands.

Unemployment and occupational injustice

Occupational therapists are well-versed in the negative consequences of unemployment and will thus recognise the adverse effects on health and wellnessI7-20. Bartley2I highlighted the effect that a spell of unemployment can have on subsequent employment patterns. However, it is our view that connections between unemployment and occupational injustice, as a priority concern for occupational therapists practicing in contexts such as South Africa, require further consideration.

Townsend22 spoke of occupational injustice hindering individuals, groups or communities from having the opportunity to fully participate in society. People living in poverty face social stigma, as well as restricted educational and work opportunities, which can prevent them from engaging in desired and culturally meaningful oc-cupations22. Occupational therapists are encouraged to explore occupations as they relate to the manner in which people experience meaning and purpose in their lives, and the consequences of their engagement in these occupations23,24. We hold the view that street vending, amongst other occupations, requires such consideration. According to Skinner25 opportunities to enter formal trade or business sector may be thwarted due to a lack of resources and skills.

Health and well-being on the street

Many hawkers are vulnerable to ill health due to the lack of shelter, exposure to the weather elements and other stressful life circumstances26. Income level was found to be a key factor in determining the accessibility of health care, placing those in the low-income bracket, as most hawkers are, in danger of neglect by the health care system27. Furthermore, hawkers often work in environments that expose them to hazards such as accidents and illnesses28.

A study in Dar Es Salaam indicated that traders are exposed to biological, ergonomic, physical and psychosocial hazards27. Hawkers often trade along pathways of congested traffic and concentrated air pollutants exacerbate conditions such as asthma, allergies, tuberculosis and chronic bronchitis. In these areas, the traders are at risk of eye irritation, dizziness, tightness of the chest, sore throats, colds and coughs29. Furthermore, the concentration and exposure to exhaust fumes can be a possible source of lead poisoning to traders30. For some hawkers, physical injury may be caused by prolonged participation in excessively strenuous physical activities such as loading and offloading their goods on a daily basis6.

The social, political and cultural environment and its impact on hawkers

There continues to be debate as to whether informal self-employment is a survival tactic or an entrepreneurial strategy31. Urbanisation, migration and economic development have led to an increase in the number of street vendors in African cities25. Street vendors face a number of difficulties outside of their control. This includes conflict with police, customers and fellow traders, poor integration into urban planning, competition for similar goods, negative public attitudes and daily physical obstructions3,25,29.

The impact of Xenophobia

Xenophobia has been defined as "the intense dislike, hatred or fear of others perceived to be strangers"32:5. Wimmer33 hypothesizes that xenophobia and racial tensions result when nationals of a country feel that immigrants threaten their space and jobs. It is this perceived threat, which has led nationals to resort to violence and exclusion in an attempt to protect their jobs and fragile economic security. The increasing rate of globalisation and the lack of available capital have resulted in foreign African nationals who live in South Africa being denied a right to their own identity by the South African nationals who share their communities. This results in a continuation of the apartheid mentality in another form and under a different guise - the protection of one's right to belong and to make a living. The violence towards, and assaults on foreign traders which results from this intolerance forces many immigrants and asylum-seekers to return to their country of origin.

METHODOLOGY

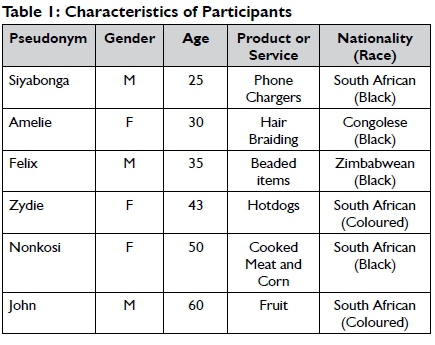

The original data collection was done by a group of six final year occupational therapy students with guidance provided by the second author. A collective case study34 was done comprising six participants who were selected through maximum variation sampling. Variation was sought in terms of age, gender, race, nationality, culture, health status, nature of business products, target market and place of trade. In order to gain access to the traders' natural environment time was spent in locations where traders were known to engage in their occupation of hawking. Having spent a day observing the traders, the student researchers considered all vendors they observed together against selection criteria for maximum variation sampling. Venders were selected to obtain as much variation as possible for each criterion. The vendors were then recruited during a second visit to the trading site.

PARTICIPANTS

The six participants lived in low-income housing or informal settle ments within Cape Town.

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and participant observation and analysed by means of an inductive content analysis. Each participant participated in two interviews, which were conducted in English. Interviews lasted between one and two hours and were digitally recorded. Questions related to how participants started street vending what skills they felt they needed to have and what helped or hindered their business. At the end of each interview, the researchers reflected on key emerging issues. Reflections obtained during participant observation were captured in journal entries throughout the research.

In order to establish trustworthiness, data collection included member check interviews. Peer debriefing was used throughout the research process and an audit trail was constructed. Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee, University of Cape Town (HREC 508/2007). Participants gave informed written consent and were assured of confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any point without prejudice to themselves.

FINDINGS

Five themes emerged from the study. These capture ambiguous choices related to the suitability of hawking as a form of self-employment and the harsh realities confronted by hawkers on a day-to-day basis. Hawking offered the means for survival and the desire to be one's own boss. This article will report on the five themes that emerged from the study.

Theme one: Reasoning around street vending as career: "I want to make a living, you see"

This theme is related to livelihood creation, being one's own boss, income generation and trading with integrity. Because street vending is an income-generating occupation, it came as no surprise that all participants cited "earning an income" as the principal reason for becoming street vendors. Although the majority of the participants enjoyed the occupation of street vending, they felt forced into the choice as a strategy for livelihood.

"Yes I can do this because I want to survive in life. If I'm sitting at home I can't survive...I'm trying to make a living for me and my kids... to buy the food for my child. 'cause I don't want my child to get suffering you see." (Siyabonga)

Zydie was the exception, she started trading following a divorce, as a means of personal survival. She was deemed to old to return to her previous job in the motor industry so she decided to generate an income for herself, escape boredom and engage in a constructive occupation during her day. Zydie shares her stall with other traders.

"Everybody is married, everybody has their own social lives, and I'm divorced. I was alone. And why sit alone at home, bored?" (Zydie)

The nature of street vending is such that daily, weekly and monthly income tends to be unpredictable. Street vendors are generally forced to keep the prices they charge very low, in order to sell their goods in a competitive market.

"You see the stuff on the market is very expensive at the moment. For us to compete against the shops, we don't stand a chance." (John)

Despite the uncertainty that street vending held for participants, many of them shared their future goals and aspirations. Hawking was thus more than a means for survival in difficult circumstances; it served as a stepping-stone towards future independence.

Deciding to be one's own boss was of significance for each of the participants.

"If I could have my stand tomorrow on my own, I would do it. I'm sick of working for other people." (Zydie)

Participants highlighted that moral and behavioural standards were necessary through the sub theme trading with integrity;

"You must have no alcohol, you must smoke no drugs, you must always come to the [place where he traded] with a clear mind." (Siyabonga)

"There is no way you can leave your place dirty; this is the council's place... you can't leave it dirty when you finished and other people must clean it for you." (John)

Despite the public's perception and opinions of hawkers, they took pride in their work, their conduct, the quality of their products and the spaces in which they traded. They adhered to the laws and regulations governing hawking so that they could be part of a network of traders, while simultaneously trying to create a space for themselves.

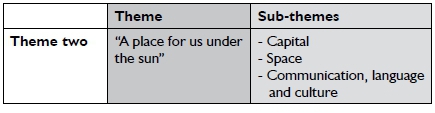

Theme two: Resource requirements for vending: "A place for us under the sun"

This theme related to the resources required to conduct business, including start-up capital, space for trading, communication skills and language and culture. Start-up capital was, for obvious reasons, an essential consideration for all participants. Most participants did not have the necessary capital to start their own businesses and were thus working for others.

"We struggled from generation to generation. The struggle is on because there is not enough capital for us." (John)

Communication amongst hawkers was deemed enjoyable, and viewed as an essential component of successful business; as well as an opportunity for social connectedness and as a means of fostering positive relationships between traders, and with their customers. Communication skills were used to negotiate and solve problems; to teach and learn from each other and to pass on wisdom and experience in their trading spaces.

"What I enjoy the most, I think talking to the customers. I mean talking to so many people; you see I enjoy doing that." (Felix)

South Africa is filled with diverse local and foreign cultures, which influence the way in which hawkers conduct their businesses and relate to others. This also demanded that they be flexible which is highlighted in the next theme.

Theme three: The need to adapt and respond to unpredictable forces: "We always change"

It was found that participants adapted their lives and street trading activities in a number of ways: by learning new skills or selling goods that there is a demand for adjusting to seasonal changes; adapting techniques used to make a sale; responding to competition and persevering.

"We always change, we always change." (Amelie)

Most of the participants made reference to learning new skills in order to trade successfully. The simple process of trial and error was seen to be fundamental to hawking and guided the participants' adaptive responses. Participants described how they learnt new skills from other hawkers through the use of observational learning.

"I just watched people doing it and then I did it also. You know what, you can learn from others..." (Felix)

The weather in Cape Town is an unpredictable phenomenon to which hawkers were forced to adapt. Their livelihoods were dependent on favourable weather conditions. Transport to and from their place of work was an expense that could not be recouped in the event of unfavourable weather.

"If [the weather forecast for rain] is 80 or 100% then we don't come, but if it's 60%, because that's what I told you we've got the stands." (Amelie)

In order to ensure that successful sales were made, participants identified the need to adapt the product or service, use marketing and advertising techniques, change their prices and respond to competition. Participants expressed how important it is to persevere and have confidence in their abilities when faced with obstacles. The support of family and friends assisted with this.

"You see if this is not in you, even if you have the capital it's not going to work, it must be in you to do it... some people may never come right in this...You must learn from childhood. From young days become a trader otherwise it's not gonna work." (John)

"You know this work is a strong work, is a difficult work. We do it just because we need, because we must. We don't have choice." (Amelie)

"Here is too much wind, it's very cold, but we are still here every day; we are here because we need something." (Zydie)

While the street vendors shared their flexibility and tenacity they also share how the need for their products and service are affected by interactions with the law resulting in confiscation of their goods.

Theme four: "What we require is their requirements"

All the participants had either witnessed or experienced interactions with the authorities surrounding their place of trade. These hac positive and negative outcomes.

"We got the place, you know they want to build the new stuff there sc we got the place, that one we're waiting for, that place...Everyone get their place...We have to pay, because we did pay already, now it's foi us, so they want to do that because they say it's not nice to be here [outside the station without a durable stall]."(Amelie)

The most commonly occurring negative outcome mentioned was the confiscation of goods by the authorities. John, who now has his stall at the railway station in specially constructed space fo vendors, was comparing the laws that governed street vendors in the apartheid era to the laws operating now.

"Ja, in apartheid years you was always on your toes, on the lookout ... " (John)

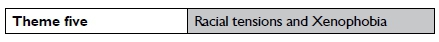

Theme Five: Racial Tensions and Xenophobia

South Africa is a country with a history of racial tension and injustice. During the course of this research, xenophobic attacks broke out across the country. This affected people from all backgrounds and areas, including those in the Western Cape. Hawkers of different nationalities felt the presence of tension and prejudices.

"They 're jealous; they say you come to take our money...there by your country from which you come, you come to steal our money. They don't like us." (Amelie)

On the opposite side of the spectrum, traders - both South African and non-South African nationals - justified the universal right to trade:

"I'm just, uh, working here for my money, then, so that one day when things are ok I can take it back to my country." (Felix)

"They are here mos to make life better for them for the year you see." (Siyabonga)

Within their daily trading interactions with customers, the hawkers experienced prejudice, which, according to them, is based on their occupation.

It appeared that hawkers of the same nationality assist one another in learning the trade and starting their businesses:

"Another friend of me he is a Zulu guy he's from Joburg. You see he introduced me to this job." (Siyabonga)

"Somalian guys yes...that's the guys they're selling chargers. In town. Yes I get the chargers there yes." "But the chargers for Chinese guys are really bad." (Siyabonga)

As illustrated by these comments, both South African and foreign national traders are affected by prejudice and intolerance between the different racial groups and nationalities in the street vending business. Although the tangible and intangible components of street vending appear similar amongst the research participants, no two hawkers' experience was the same. The importance that individual hawkers placed on various factors differed, as did the way in which the participants interacted with these factors. This observation emphasizes the fact that each participant had a unique experience of hawking, adding to the richness of the data collected and interpreted through phenomenological research35.

DISCUSSION

The contribution of street vending as an empowering occupation was felt to be relevant in a country in which a large proportion of the population face severe resource constraints. Bartley21 reported on the link between ill health and unemployment. Occupational therapists are interested in occupations which influence well-being23. For the participants, the fact that they were employed impacted positively on their wellbeing. They were able to develop and participate in social networks and felt proud to be contributing financially to their families. Their sense of doing impacted positively on their health36.

The occupation of work has the potential to add meaning to a person's life, and individuals engage in a variety of work occupations in order to meet their financial and other needs39. When the work occupation an individual engages in aligns with the interests, values, and goals of that person, personal fulfilment is likely to occur and the individual will find a means to become what he or she aims to be36,40. Conversely, when the work occupation does not support a person's goals, values and interests, an individual might experience decreased health and well-being.

The environment in terms of the socio-economic and political context of South Africa notably influences street vending. Although apartheid ended in 1994, South Africans are still dealing with racial tension and injustice as experienced by traders from different nationalities in the street trading business. Within their daily trading interactions, hawkers continue to experience stigma, based, according to them, more on their occupation than their nationality. Street vendors are thus not recognised as being economically active members of society engaging in productive occupation. This should change through recognition of the contribution of informal traders to the informal sector of the economy. The South African government started exploring ways to create jobs and fight poverty through Hawker-Powerl. This process will only be successful if street vendors are viewed as business owners contributing to job creation and economic growth.

Hammell and Iwama23,38 speak about occupational rights as the right of all people to engage in meaningful occupations which contribute to self and community wellbeing. A legislative environment that supports trade, rather than hinders it, is essential to assist traders who are already facing harsh environmental conditions on a daily basis. This will go a long way towards legitimising the efforts of hawkers in order to contribute to their families and communities.

It was noted that a significant attraction of hawking is the opportunity to work independently. Managing their own businesses gave hawkers a sense of agency and control over their lives. This autonomy promotes self-esteem within the individual and encourages a sense of well-being. They described hawking not as a disorganized burden on society, but as legitimate businesses that contribute to their families, communities and the economic growth of South Africa. This is different from the common perceptions held by the general public, and if we are to acknowledge their contribution to the economy we have to improve our understanding of the desirability of this occupation and the consequences involved in engaging in it.

It also appears that although hawkers engage in the occupation of street vending, they do not feel defined by it. One needs to acknowledge that many people engage in hawking in order to survive and meet their basic needs due to poverty and unemployment, and that street vending may not be an individual's chosen work occupation12,37. A new approach might be needed to assess the suitability of occupations; one that allows for understanding the transformative value that occupations can give to livelihood creation, rather than focusing narrowly on their therapeutic use or potential to contribute to personal meaning.

The findings suggest that opportunities for self-employment have the potential to alleviate poverty and promote pride and self-worth. Further research could be conducted as to whether or not street vending and other self-employment occupations really achieve this.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

During the research, three of the participants were unable to participate in the second interview. This might be indicative of the transient nature of street vendor's existence that adds to the challenge of the occupation. Traders generally have to re-construct trade spaces (for example stalls) every day and many of them move to different locations regularly.

None of the participants were white or Indian and thus the sample was not reflective of the population of South Africa. Interviews were conducted in English, which was not the participants' home language. Similarly, the interviewers and interviewees differed in terms of race, culture and socio-economic status. Whilst these differences were not observed to have a particular impact on the quality of the interviews, it might nonetheless have been the case. The study was also done in one geographical region and results in rural or other cities might be different.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study provides occupational therapists with some insights into the meaning and purpose dimensions of hawking as situated within social, political, economic and cultural perspectives. It was found to be a relevant and empowering occupation for a country in which a large proportion of the population face severe resource constraints and unemployment.

While each participant's experience of hawking was found to be unique, the socio-political and legal environment of South Africa has an impact on the experiences and activities of hawkers. The xenophobic attacks, which occurred during the research, highlight the racial tensions that still exist in South Africa.

We hold the view that occupational therapists should generate evidence for public health policy addressing population needs and reducing inequalities in society. Whether occupational justice is promoted or hindered by the occupation of hawking remains contested. We hope this paper will provide some understanding of what people do, and how they experience what they do, in the context of health-giving occupations.

There is an opportunity for occupational therapists involved in the area of economic empowerment and development, to look at integrating their clients into supportive environments created by government initiatives to establish small-, and micro-enterprises. This could also provide opportunities for occupational therapists to liaise with other government sectors, outside of health, in order to influence regulations governing street vending and to aide hawkers in accessing financial services, business development skills, infrastructure support and amenities access.

Hawking provides individuals with a sense of pride in being in charge of their own welfare, as well as in their legitimate contribution to the economic growth of families, communities and South Africa at large. For occupational therapists this is an invitation to improve our understanding of hawking.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals who were students in the Division of Occupational Therapy at the University of Cape Town at the time that the study was carried out:

Meghan Dawson, Karen Duthie, Mary Enslin, Lisa McGowan, Ma'ayan van der Westhuizen, Amy Wilkes-

REFERENCES

1. Nevin, T., The economic impact of the 'Happy Hawker'. African Business. 2004; 301: 42-43. [ Links ]

2. Steinberg J. Crime prevention goes abroad: Policy transfer and policing in post-apartheid South Africa. Theoretical Criminology, 2011. 15(4): 349-364. [ Links ]

3. Davies R and Thurlow J. Formal-informal economy linkages and unemployment in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 2010. 78(4):437-459. [ Links ]

4. Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, Kakuma R Corrigall J, Joska JA, Swartz L and Patel V Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Social science and medicine. 2010; 71(3): 517-528. [ Links ]

5. Ligthelm A. Size estimate of the informal sector in South Africa. Southern African Business Review. 2006; 10(2): 32-52. [ Links ]

6. Mitullah WV Street vending in African cities: a synthesis of empirical findings from Kenya, Cote D'Ivoire, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa. Background paper for the WDR, 2005. [ Links ]

7. Commission, NP National Development Plan: Vision 2030. Pretoria: National Planning Commission; 2011. [ Links ]

8. Labbe E, Steyn M and Loots M. Life expectancy of the 20th century Venda: A compilation of skeletal and cemetery data. HOMO-Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 2008; 59(3): 189-207. [ Links ]

9. Vahed G. Control and repression: the plight of Indian hawkers and flower sellers in Durban, 1910-1948. The International journal of African historical studies. 1999; 32(1): 19-48. [ Links ]

10. Peberdy S. The participation of non-South Africans in street trading in South Africa and in regional cross-border trade: Implications for immigration policy and customs agreements. Briefing Paper for the Green Paper Task Team on International Migration. Pretoria: 1997: 12. [ Links ]

11. City of Johannesburg. The rise and rise of hawking in the city, in Joburg, my City, our Future: Growth and Development Strategy 20402007. City of Johannesburg: Johannesburg. [ Links ]

12. Khotkina Z. Employment in the informal sector. Anthropology & archeology of Eurasia. 2007; 45(4): 42-55. [ Links ]

13. Celik E. The Exclusion of Street Traders from the Benefits of the FIFA 20I0 World Cup in South Africa. African Journal of Business and Economic Research. 2011; 6(1). [ Links ]

14. Sassen SR. Women's experiences of street trading in Cape Town and its impact on their well-being. 2013; University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

15. Sidzatane NJ and Maharaj P On the fringe of the economy: Migrant street traders in Durban. In: Urban Forum. Springer; 2013. [ Links ]

16. Woodward D, Rolfe R Ligthelm A and Guimaraes P The viability of informal microenterprise in South Africa. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship. 2011; 16(01): 65-86. [ Links ]

17. Baumberg B. The global economic burden of alcohol: a review and some suggestions. Drug and alcohol review. 2006; 25(6): 537-551. [ Links ]

18. Dunn EC, Wewiorski NJ and Rogers ES. The meaning and importance of employment to people in recovery from serious mental illness: results of a qualitative study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2008; 32(1): 59. [ Links ]

19. Van Niekerk L. Participation in work: A human rights issue for people with psychiatric disabilities. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 38(1): 9-15. [ Links ]

20. Lorenzo T, Van Niekerk L and Mdlokolo P. Economic Empowerment and black disabled entrepreneurs: negotiating partnerships in Cape Town, South Africa. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007; 29(5): 429-436. [ Links ]

21. Bartley M. Unemployment and ill health: understanding the relationship. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 1994; 48(4): 333-337. [ Links ]

22. Townsend E, Galipeault JP, Gliddon K, Little S, Moore C and Klein BS. Reflections on power and justice in enabling occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2003; 70(2): 74-87. [ Links ]

23. Hammell KW. Reflections on... well-being and occupational rights. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 75(1): 61-64. [ Links ]

24. Hammel KW. Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004; 71(5): 296-305. [ Links ]

25. Skinner C. Street trade in Africa: A review 2008: School of Development Studies. University of Kwazulu-Natal. [ Links ]

26. Hunter N and Skinner C. Foreign street traders working in innercity Durban: Local government policy challenges. In: Urban Forum. Springer; 2003. [ Links ]

27. Pick WM, Ross MH and Dada Y The reproductive and occupational health of women street vendors in Johannesburg, South Africa. Social science and medicine. 2002; 54(2): 193-204. [ Links ]

28. Oyefara JL. Family background, sexual behaviour and HIV/AIDS vulnerability of female street hawkers in Lagos metropolis, Nigeria. International Social Science Journal. 2005; 57(186): 687-698. [ Links ]

29. Kongtip P Thongsuk W, Yoosook W and Chantanakul S. Health effects of metropolitan traffic-related air pollutants on street vendors. Atmospheric Environment. 2006; 40(37): 7138-7145. [ Links ]

30. Furman A and Laleli M. Semi-occupational exposure to lead: a case study of child and adolescent street vendors in Istanbul. Environmental research. 2000; 83(1): 41-45. [ Links ]

31. Temkin B. Informal Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Entrepreneurship or Survivalist Strategy? Some Implications for Public Policy. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2009; 9(1): 135-156. [ Links ]

32. Nyamnjoh FB. Insiders and outsiders: citizenship and xenophobia in contemporary Southern Africa. 2006; Zed Books. [ Links ]

33. Wimmer A. Explaining xenophobia and racism: A critical review of current research approaches. Ethnic and racial studies. 1997; 20(1): 17-41. [ Links ]

34. Stake RE. Multiple Case Study Analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [ Links ]

35. Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage; 2013. [ Links ]

36. Wilcock AAA. Occupation and health: Are they one and the same? Journal of Occupational Science. 2007; 14(1): 3-8. [ Links ]

37. Roy MA and Wheeler D. A survey of micro-enterprise in urban West Africa: drivers shaping the sector. Development in Practice. 2006; 16(5): 452-464. [ Links ]

38. Hammell KRW and Iwama MK. Well-being and occupational rights: An imperative for critical occupational therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 19(5): 385-394. [ Links ]

39. Van Niekerk L. Participation in work: A source of wellness for people with psychiatric disability. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation. 2009; 32(4): 455-465. [ Links ]

40. van Niekerk L. Identity construction and participation in work: Learning from the experiences of persons with psychiatric disability. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 23(2): 107-114. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ms Fadia Gamieldien

Email: FadiaGamieldien@uct.ac.za

Tel: +27 21 406 6404

1 Dedicated spaces for taxi's to park while waiting for customers