Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.46 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a9

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Having a child with cancer: African mothers' perspective

Deshini NaidooI; Thavanesi GurayahII; Nabeela KharvaIII; Tehmi StottIII; Stacey Jane TrendIII; Thabile MamaneIII; Simiso MtoloIII

IB OT (UDW), M OT (UKZN). School of Health Sciences, Occupational Therapy Department, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal (Westville)

IIB OT (UDW), M OT (UDW). School of Health Sciences, Occupational Therapy Department, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal (Westville)

IIIB OT (UKZN). At the time of the study these authors were final year occupational therapy students at UKZN

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The study was conducted in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Six boarder mothers, who lived with their children in the CHOC house while their children received treatment for cancer, were interviewed for the study.

Objective of study: The objective was to explore the lived experiences of mothers from rural and peri-urban areas when their children had cancer. Specifically information on occupational balance and disruption, as well as shifting responsibilities, was explored.

METHODS: A single focus group followed by individual interviews were conducted.

FINDINGS: The findings revealed that some African communities believe that children do not get cancer. There was a lack of factual information around the condition, which perpetuated the stigmatisation of these families. They felt isolated and could not access any community support as a result. Mothers experienced occupational disruption, as well as guilt and self-blame when their children had cancer.

RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE: Support and information for mothers hospitalised with sick children should form part of occupational therapy intervention.

LIMITATION AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH: These findings are applicable to African mothers from both a peri-urban and rural context in KwaZulu Natal. Further research with mothers across South Africa would be useful to expand on the research findings and would potentially assist in programme development.

Key words: mothers perspectives, cancer, stigma, occupational disruption, African beliefs

INTRODUCTION AND RATIONALE FOR THE STUDY

The Childhood Cancer Foundation of South Africa states that one in six hundred children will be affected by cancer before they reach the age of sixteen1. The symptoms of childhood cancers are difficult to identify as they may mimic other common illnesses and conditions to which children are prone. Stefan2 reported that while it is possible to treat 80% of childhood malignancies, the cure rate is lower in developing countries such as South Africa, where the condition is often underreported. Despite the prevalence of childhood cancer in South Africa there is limited literature around the experiences of parents who have had a child with cancer, and interrogating the effects that this diagnosis may have on the parents.

Globally it is acknowledged that childhood cancers can have physical, medical and psychological effects on children. Furthermore, the diagnosis of childhood cancer is described as one of the most intense and painful experiences that a parent can have3. Parents have reported feelings of distress, shock, coping difficulties and emotional pain as part of the psychological impact of the diagnosis4. Parents of children with cancer are considered the "untreated patients", owing to the high levels of anxiety and stress experienced, and the continuous fear of relapse5. Psychological problems may be difficult to assess or identify as they often overlap with many everyday problems and challenges. However it is crucial for health professionals to be able to identify and provide intervention for the psychological difficulties of the family that may ensue in the wake of a cancer diagnosis.

Compas et a16 identified that the cancer diagnosis of a child can be distressing for the family as a whole. Similarly other studies5,7 noted that the adjustment to having a child with cancer can have a significant impact on the psychological well-being of the family members and their functioning, within the household and the community. The effects of having a child with cancer may not always be overt, but rather imbedded in psychological challenges, and may manifest as impairments in the parents' coping style or execution of their daily responsibilities and occupational choices.

Anecdotally within the South African setting, it has been noted that it is mainly the mothers who will reside with the child who is undergoing treatment as an in-patient. The review of Vrijmoet-Wi-ersma et a13 found that parents' emotional stress reactions emerged around the time of diagnosis, with mothers being affected more than fathers. From a local perspective, Jithoo8 explored parents' experience of the communication process and the support and guidance needed for parents of children with cancer. She found that communication around the illness was limited to medical matters with the emotional issues being neglected. Furthermore, it emerged that parents were overwhelmed by their experience and expressed a need for psychological intervention. However there is limited research on the experience of mothers of children with cancer in the rural and peri-urban contexts of South Africa. Furthermore, there is a dearth of research on the effect of having a child with cancer on the daily activities and roles of mothers in these contexts. In light of this gap in the literature, the researchers believed that there was a need for a study to explore the lived experiences of mothers with children afflicted with cancers in order to inform occupational therapy practice. This study was designed to explore the lived experience of the mothers who have children with cancer and identify how this affected their daily lives. The aim of this study was to explore the experiences and psychological challenges faced by mothers with children who have childhood cancers. The researchers further wished to explore the occupational effects of having a child with cancer and the coping mechanism used by mothers. This was aimed at creating deeper insight into this phenomenon to guide clinicians' provision of intervention. This paper will specifically report on the psychological and occupational effects on the lives of mothers who provide care for children with childhood cancer within the context of KwaZulu Natal in South Africa.

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative cross-sectional research design was used to explore the lived experiences of mothers of children with cancer. Qualitative methodology enabled the researchers to gain insight into the participants' contexts and their personal experiences.

The study was conducted at the Children's Haematology Oncology Clinics (CHOC) childhood cancer foundation house in Durban South Africa. CHOC is a non-profit organisation which was established in 1979. The foundation offers free accommodation to the children and their care givers whilst receiving medical intervention at Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital (IALCH), a local tertiary level hospital. The clients travel from their homes across the province to IALCH for their oncology regime, and the accommodation provided by CHOC allows a parent/caregiver to stay with the child whilst receiving treatment.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit the participants for the study. The inclusion criteria included caregivers who had a child under the age of eighteen, spoke IsiZulu or English, and who were resident at CHOC at the time of the study. Six females aged twenty four to forty two years of age who lived in rural and peri-urban areas in KwaZulu Natal (a province in South Africa) participated in the study. The participants were unemployed and their monthly income ranged between RI000 to R3450, with most caregivers receiving a child support grant for their children. The participants had between two to five other children who remained at home.

A pilot study was conducted prior to data collection to test the questions, in order to improve trustworthiness of the data and reduce ambiguity of questions. Data was collected using one focus group and two semi-structured interviews. The focus group and interviews were audio-recorded to ensure accuracy in transcription. Open-ended questions were asked, focussing on the lived experiences of the mothers, with regard to having a child with cancer. Each participant was given a pseudonym to ensure anonymity

The semi-structured interviews were conducted in the same week as the focus group. All the mothers were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews and two mothers volunteered to participate. These interviews were used to deepen the enquiry into the themes of interest that emerged from the focus group. In this way, the findings from the semi-structured interviews allowed the researchers to add depth to the findings. The focus group and the semi-structured interviews were conducted in IsiZulu by an isiZulu speaking researcher as this was the participants' home language. The researchers had both the focus group and the individual interviews translated from IsiZulu into English. These transcriptions were verified and cross checked by an objective third party. Thematic Analysis was employed to analyse the verbatim transcripts. Deductive reasoning using the research questions was used to generate the initial codes, whilst inductive reasoning was used to reduce the number of codes and refine the main themes. The researchers obtained ethical approval from the University of KwaZulu Natal Ethics Committee.

Finally the data was analysed separately by each member of the research team to improve trustworthiness of the data. Once the data was analysed, the researchers had to achieve consensus regarding the themes and allow for analyst triangulation.

FINDINGS

There were four main themes that emerged in this study, namely 'community insight and beliefs', 'the emotional reactions to having a child with cancer', 'factors that promoted resilence' and 'the impact of having a a child with cancer on the participants' occupational roles'. The themes and the subthemes are outlined in the section that follows.

Theme 1: The Mothers' Emotional Reactions to Having a Child with Cancer

Guilt and Anxiety

The mothers experienced self-blame relating to their child having cancer, as well as guilt for leaving the family members at home, whilst they remained with their sick child at CHOC. The mothers reported feeling anxious and uninformed regarding matters surrounding their child's diagnosis of cancer and the treatment process.

I used to ask myself why I am not the sick one, why must it be my child? Agnes

What hurts me the most is that the other children at home always call me asking when am I coming back home. Gloria

What saddens me the most is that I left the other kids with their father only... and everyone knows that males are not good at caring for the children. Busi

I am very troubled since most of the work has to be done by my eldest child who is only 14 years of age. Eunice

Frustration

Feelings of frustration were clearly vocalised by the mothers participating in both the focus group and individual interviews. These feelings were directed at their child's illness and the community due a lack of knowledge and support from them regarding the diagnosis of cancer. The mothers' expressed feeling anxious and frustrated at the disruption of their occupational roles as mothers.

I have explained at length that there are many children in the hospital I have encountered with cancer. Some people still do not believe me up until this point. Busi

Theme 2: Community Insight and Beliefs

Traditional African Beliefs

The mothers' all had a traditional African belief paradigm and were representative of the rural and peri-urban communities from which they came. They believed that their communities felt that their children had cancer due to the ill-will or the curse of an ancestor. The mothers' reported that they had first consulted traditional healers before seeking Western medical intervention, due to the traditional belief systems that they practiced.

They (the ancestors) have the belief that it is a traditional illness. Busi

We have tried traditional healers and still there was no result. Eunice

Community Silences around Cancer and lack of knowledge

The mothers' reported that they felt alone, as the community did not acknowledge that their children could have cancer, and did not openly discuss the illness. Furthermore, it was found that the mothers, as well as their communities of origin, generally lacked knowledge and insight into childhood cancers, with the result that the mothers did not feel accepted within their communities. In addition, non-disclosure of the children's diagnoses prevented the family from accessing the support of the extended family and community, which serves as a buffer when the mother was away. It also emerged from the mothers that the communities had greater knowledge and understanding of HIV/AIDS than they did of cancer, and particularly of childhood cancers. The quotes that follow give voice to these feelings of alienation and loneliness of the mothers.

I was really hurt when my child was diagnosed since I had not ever heard in my community that there is a child with cancer..., I was going to be the first one. Thembi

The community does not accept it very easily that a young child has cancer especially when no one in the family has ever had cancer. Gloria

Sometimes you wish that your child had TB or HIV/AIDS because you know that there is medication that the child can take and live a normal life. Eunice

Theme 3: Factors That Promoted Resilience in the mothers

Family support and the advantages of being at CHOC

The family members provided emotional support to the mothers with regular telephone calls. In addition to the telephonic communication, one mother reported that her relative visited her on a regular basis. In addition, the mothers found that the peer support resulting from residing at CHOC was beneficial as they found comfort in sharing their experiences, and realised that their children were not alone with a cancer diagnosis. This brought some emotional reassurance that they were not alone.

I get calls from both families (from my side and the husband's side). Having people supporting you during this time is an advantage for me because I feel loved and comforted during these trying times. Lebo

My brother ...always calls and visits us here at CHOC... I can safely say that he is like my parent. Agnes

The fact that we live together here at CHOC as mothers and we share our experiences even though our children's sicknesses are different. Busi

When I came to CHOC, I saw that I am not the only one with this sickness. I got used to understanding that cancer is something that exists in children and not in adults only. Gloria

Coping Mechanisms and Ways to cope Three common coping mechanisms of the mothers emerged in the research, namely prayer, acceptance and optimism. Acceptance of their child's condition helped them come to terms with the diagnosis. Optimism in the form of hope allowed the mothers to believe that they would survive this trying time in their lives.

I sometimes say God is with me since my child survived chemotherapy. Agnes

What I can say is that you first have to accept that cancer is a reality. Agnes

"I am feeling much better now as compared to before, because I can see him playing around and he is normal. I still have hope for him" Gloria

Theme 4: Impact on Mothers' Occupational Roles

Mothers' Responsibilities

All Mothers were unemployed at the time of the study, and their daily occupations revolved around home maintenance, and taking care of their families. Some mothers disclosed that they worked in the gardens and fields of the home as well. This was not seen as a formal occupation with any form of remuneration, but part of the role as a wife.

Since I stay in a rural area and not in the townships, thus the only work I have been doing is preparing my child for school, cooking and doing the laundry. Agnes

I used to do home chores and farm as well. Eunice

Disruption at Home and shifting responsibilities

The mothers showed concern over the disruptions at home due to their absence. The family members had to alter their occupational roles in order to absorb the duties of the mother. This was accompanied by feelings of distress and guilt from the mothers, as they expressed their lack of confidence in another individual's ability to take care of their families.

It is difficult being away from home because everything stops, since most of the things at home are done by you as a mother. There is absolutely nothing that goes on within the home without me. Gloria

I feel so sad and worried about the situation at home, because even if there is shortage of groceries at home, the kids wait for me until I come back. Gloria

My eldest child, but their father also helps out especially when it comes to cooking. I am very troubled since most of the work has to be done by my eldest child who is only 14 years of age. Eunice

DISCUSSION

Community insights and beliefs about cancer

The researchers identified that the mothers represented a microcosm of the communities from which they came. With this in mind, the mothers were not seen as mutually exclusive individuals from the community, but rather as being embedded in their communities.

Traditional beliefs emerged as a factor that could influence the mothers' and their communities' views on cancer. Mothers admitted to having consulted with traditional healers regarding their children's illnesses prior to seeking western medical help. They initially believed that cancer was a result of traditional causes, such as a curse on the family or the ancestors being angry. In view of this, it was not surprising to find that the mothers first took their children to traditional healers, before taking them to hospitals when their children's health did not improve. This may have contributed to the late diagnosis of cancer in some children, resulting in a poorer prognosis in these cases.

There appeared to be a lack of understanding with regards to cancer as a medical condition, and how it affected people from varying age groups within the population. The personal experience of having a child with cancer brought more awareness of the condition, but the mothers lacked factual knowledge of cancer. This was despite their exposure and access to medical staff who were available to pass on reliable information and promote insight into the condition. Keselman's study9 reported that there is a need to draw on communication and social science theories of information to ensure better communication between health providers and clients. Interestingly, the mothers and communities appeared to have a better understanding of HIV/AIDS including the prevalence of the condition in children. This may have been due in part to the widespread dissemination of information regarding HIV/AIDS by the national and provincial South African (SA) Department of Health.

The mothers' access to information on childhood cancers was limited, when compared to HIV/AIDS, as anecdotally it was noted that there was limited information campaigns on childhood cancers by the SA National Department of Health. This is a gap in service delivery as the National Service Delivery Agreements identifies childhood health as a priority10. Furthermore, the participants who predominantly lived in rural and peri-urban communities, had no access to the internet and there was limited exposure to information on childhood cancers on the radio and on television in KwaZulu-Natal. This left the mothers and their communities with limited sources of information such as word of mouth, to retrieve information, around conditions such as cancer that affected their children.

Mosavel, Simon and Ahmed11 found that the lack of knowledge of cancer is common in the South African context, and that communities play a large role in the dissemination of false information, and the ensuing creation of stigma around cancer. This was reiterated by the mothers' description of their communities' beliefs that cancer could not be associated with a child, as it was presumed to be an adult condition for those with a family history.

The three inter-linked areas that created a picture of the community's insights were traditional beliefs, lack of insight and knowledge, and silence in the community. The findings indicate that traditional beliefs shape the way in which African individuals may approach and understand the diagnosis of cancer. This has an effect on the communities' and the mothers' insight into the condition. Emotions such as guilt emanating from traditional beliefs, and fear of judgement from the community, may urge the mothers to remain silent regarding their childs' diagnosis. This perpetuated the cycle of a lack of knowledge and insight of the mothers, as well as the community. It further promoted the value of remaining silent and contributed toward non- disclosure of the diagnosis. The mothers seemed to have used silence to protect themselves from possible stigmatisation and ostracisation by the community, but this silence may in fact be fuelling the former, as it reinforced the shame and guilt in relation to a childhood cancer diagnosis.

Emotional reactions to having a child with cancer

The mother's feelings of guilt and frustration appeared to be connected to the community's traditional African beliefs, their disbelief at the cancer diagnosis, and the anxiety resulting from the shift of occupational roles at home.

The mothers felt they were somewhat responsible for their child's diagnosis of cancer. This was consistent with literature that stated it was normal to experience feelings of guilt, anger and fear when your child was diagnosed with a life threatening condition12. It was noted that the guilt experienced by the mothers was predominantly in response to their role changes to both the sick child, as well as their "healthy" children at home. The American Cancer Society13:lreported that cancer created "an instant crisis in the life of all family members and that the course of daily life stops or changes course." Guilt arose in the mothers as they felt they were neglecting their family members at home, and had made the sick child their priority. Smith14 reported that mothers felt that they had caused the illness. In addition, these women may also have felt that they were being punished for something that they had done in their lives, or that they hadn't taken good care of themselves whilst they were pregnant.

This resulted in a vicious cycle existing between the mother's feelings of guilt, their lack of knowledge and poor insight regarding cancer. Mothers blamed themselves for their child's diagnosis which caused immense guilt, as they did not have sufficient knowledge to understand that this was not the aetiology of the cancer. This feeling of guilt prevented the mothers from openly communicating and interacting with the medical staff, which further maintained the status quo of the lack of knowledge and insight regarding cancer.

The mothers expressed feelings of uncertainty towards the unpredictability of the course of cancer which could be directly attributed to their lack of knowledge and poor insight. This was consistent with the literature which indicated that parents were susceptible to feelings of helplessness, fear, stress and despair in response to the unpredictable nature of cancer7,15. Similarly, Maunder16 explained that the parental uncertainty in childhood cancer was linked to the constant fear of consequences like relapse or death.

Coping mechanisms used

The mothers only returned home to their extended families on a limited basis due to a lack of finances and transportation resources. The mothers reported that they elicited emotional support from their family members via telephonic communication. This highlighted the reliance on telephonic communication, especially mobiles devices, and the need for family support. It was important to note there was a sense of strength and comfort when the mothers spoke of the support from their family members, even though it was only telephonic contact. The phone calls to and from family allowed the mothers to stay positive and remain hopeful that their children would respond to the treatment. This resonated with the findings of Fletcher et al17, who found that social support is a strong pillar to coping. Furthermore, the mothers chose to hold on to the hope that their children would fully recover. Although hope cannot be concretised, it emerged as a prominent coping mechanism. The mothers indicated that their spiritual beliefs helped bolster their spirits as they prayed to keep strong. However, there was no mention of a specific religion, and the spiritual beliefs mentioned could include ancestor worship.

Another important factor that assisted the mothers with their adverse situation was the benefit of living at a residential facility like CHOC. The mothers had peace of mind in knowing that their sick children's basic needs were being met. This included the basic needs for food, shelter, security and stimulation in the form of play. CHOC is situated on the hospital premises, which reduced the travel costs required to access treatment, which was helpful given their financial limitations. The mothers resided in areas that were geographically distant from the hospital, but still felt it was important to be present during the hospitalisation of their children. Björk et all8concurred that it was essential that parents assume roles of comforter and supporter for their children during their treatment process. Furthermore, parents facilitated the recovery process through allowing themselves to become a source of security, and physical and emotional contact for their children. Residing at CHOC enabled the parents to assume these roles. In this way mothers and their children were able to reside close to the oncology unit, where the children were able to easily access all of their treatments, while having the emotional support of their mother. Additionally the mother's presence was vital in maintaining the role of an attachment figure for the child19.

It was highlighted that the parents residing at CHOC shared a common reality that their children had cancer. This indicated a feeling of universality in contrast to feeling alone. Residing in one house forced the mothers to confront the reality that they were not the only ones with a child with cancer. This enabled the mothers to speak freely and openly about cancer, and enabled them to form a new community, one that allowed for emotional expression, acceptance and confrontation of their child's condition, in tandem with the psychosocial support it generated. The support and coping mechanisms that have been identified in this study appeared to be passive in nature. Mothers contacted their families telephonically, identified with one another at the CHOC house, and would seek comfort in knowing that they were not alone, which enabled the mothers to survive their daily lives, however it did not necessarily put them in a position of empowerment.

Impact on Mothers Occupational Roles

One of the areas that the researchers were particularly interested in was the effect of the hospital stay on the mothers' daily lives. It was found that all the mothers were unemployed prior to the onset of their children's illnesses. Despite having non-renumerated work the mothers had roles and duties as part of their daily function of being wives and mothers. The mothers reported that the cultural norm in their communities was for the females to carry out household chores and care for the children. Each mother had a daily occupation of fulfilling domestic tasks like food preparation, cleaning the home and caring for one or more children, which meant that their daily occupations had changed very little since they had been at CHOC Durban, as these tasks were still being performed, albeit to a lesser extent. The difference arose in the context of where it was being done, and the fact that it benefitted just one child in the family.

Christiansen and Townsend define occupational disruption as a "temporary condition of being restricted from participation in necessary or meaningful occupations such as that caused by illness"20:366. This study found that not only was the sick child's occupation disrupted, but that of the family as well. The mothers' daily tasks were essentially unchanged but existed in a different context, however, with the households they had left behind, experiencing the most disruption.

Mothers showed concern over the fact that they played a key role in the running of the home, and that their absence had allowed for disruption and possible dysfunction at home. This situation was inescapable, because in order to obtain access to health care for their sick child, they had to travel great distances from their homes. The poor socio-economic backgrounds of these mothers limited their ability to return home frequently in order to alleviate the disruption that was being encountered there. This was an added stress for these mothers. Apart from this, leaving the sick child at the hospital to return to the rest of the family did not come across as an option for the mothers. This concurs with the findings of Angström-Brännström et al.21 who found that parents gained comfort when they were physically and emotionally close to the sick child.

To accommodate the changes and disruption in the absence of the mothers at home, household members had to shift their responsibilities. For the mothers this felt less than ideal, with older children and fathers having to take on the daily occupational roles. The mothers seemed unsure of the family's coping abilities, which added to their feelings of guilt and anxiety for the family they left behind. The entire family, whether present at the hospital or distantly in the homestead, were struggling to survive and regain occupational and emotional normality due to the child having cancer, as well as the disruptions at home.

Ubuntu is an important African value where the interests of the community supersede those of the individua122,23. Within the African context one may fully expect the family members' occupational survival to be aided by Ubuntu, which can be seen in the actions of the extended family and community.

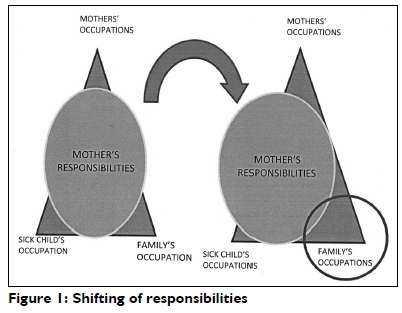

However this was not seen with every family. One mother had received support from her extended family in taking care of her family at home, however the remaining five mothers had only identified their nuclear families as a support. Several mothers had indicated that the community did not know where they were, or about their child's condition, as this was not disclosed. For this reason, the community were unable to assist these families due to ignorance of the situation, which led to further strain on the families in terms of compensating for the mothers absence. The shifting responsibilities are reflected below in Figure 1.

The sphere on the diagram represented the mothers' responsibilities, while the triangle represented the occupations of the mother, child and family. In the first diagram, the sphere representing the mothers' occupations is in the centre indicating normal and balanced occupational functioning by each mother.

In the second diagram, although the sphere representing the mothers' responsibilities had not decreased in size, it had deviated towards the sick child. This substantially increased the responsibility on the family to compensate for the mothers' absence, by taking over her occupations in the home, which represented the occupational disruption in the home.

CONCLUSION & RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper has outlined the socio-emotional and occupational effects of having a child with cancer on the lives of African mothers from KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Furthermore, the lack of knowledge and insight around cancer within the rural and peri-urban communities has been highlighted. This has raised the issue of the need for improved communication between medical staff and mothers, together with creating an environment that will provide support to the mothers and create opportunities to gain insight into cancer through shared experiences. Greater efforts need to be placed on improving the awareness of the community about childhood cancer and demystifying the myths, so that the mothers can gain support from the community to help their families through these adverse situations. The study further revealed that the mothers were susceptible to occupational risk factors, particularly occupational disruption and imbalance, and that occupational therapists needed to address these concerns of the mothers when treating the children with cancer.

A limitation of the study is the small sample size and the findings relate only to African mothers who were residents at CHOC at the time of the study. The findings cannot be extended to mothers of other race groups in the province, who may not necessarily cope with a child with cancer in the same way.

REFERENCES

1. Childhood Cancer Foundation South Africa. 2015. http://www.choc.org.za/childhood-cancer/cancer-facts.html. ( 4 July 2016). [ Links ]

2. Stefan DC. Epidemiology of childhood cancer and the SACCSG tumour registry. Continuing Medical Education, 2010; 28(7): 3. [ Links ]

3. Vrijmoet-Wiersma C, van Klink C, Kolk H, Koopman H, Ball L and Engeler R. Assessment of parental psychological stess in pediatric cancer: A review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 2008; 33: 697-706. [ Links ]

4. National Cancer Insitute at the National Institute of Health. Pediatric Supportive Care. 2013. <http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/pediatric/healt hprofessional/page3> (10 September 2014). [ Links ]

5. Rodriguez EM, Dunn MJ, Zuckerman T, Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA, Compas BE. Cancer-related sources of stress for children with cancer and their parents. Journal of Paediatric Psychology, 2012; 37: 185-197. [ Links ]

6. Compas BE, Desjardins L, Vannatta K, Young-Saleme T, Rodriguez EM, Dunn M, Bemis H, Snyder S and Gerhardt CA. Children and Adolescents Coping With Cancer: Self- and Parent Reports of Coping and Anxiety/Depression. Health Psychologist, 2014; 33(8):853-861. [ Links ]

7. Bemis H, Yarboi J, Gerhardt CA, Vannatta, K, Desjardins L, Murphy LK, Rodriguez EM and Compas BE. Childhood Cancer in Context: Sociodemographic Factors, Stress, and Psychological Distress among Mothers and Children. Journal of Paediatric Psychology, 2015; 1-9. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv024. [ Links ]

8. Jithoo V. To tell or not to tell; the childhood cancer conundrum: parental communication and information-seeking. South African Journal of Psychology, 2010; 40(3): 351-360. [ Links ]

9. Keselman A, Logan R, Smith CA, Leroy G and Zeng-Treitler Q. Developing Informatics Tools and Strategies for consumer-centered Health Communication. Journal of American Medical Information Association, 2008; 15(4): 473-483. DOI: 10.1197/jamia.M2744. [ Links ]

10. Republic of South Africa. Department of Health: Strategic health plan 2014-2019. Pretoria. Retrieved from https://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/SA-DoH-Strategic-Plan-2014-to-2019.pdf. ( 31 October 2016). [ Links ]

11. Mosavel M, Simon C, and Ahmed R. Cancer Perceptions of South African Mothers and Daughters: Implications for Health Promotion Programs. Health Care Women International, 2010; 31 (9): 784-800. [ Links ]

12. Dunn M, Rodriguez EM, Barnwell A, Grossenbacher J, Vannatta K, Gerhardt C and Compas, BE. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Parents of Children with Cancer within Six Months of Diagnosis. Health Psychology, 2011; 31(2): 176-185. DOI: 10.1037/a0025545. [ Links ]

13. American Cancer Society. 2015. <http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/002287-pdf.> (1 August 2015). [ Links ]

14. Smith PG. You are not Alone: For parents when they learn their child has a disability. News Digest, 2010; 20: 3. [ Links ]

15. Gibbins J, Steinhardt K, and Beinart H. A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies Exploring the Experience of Parents Whose Child Is Diagnosed and Treated for Cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 2012; 29(5): 253-71. DOI: 10.1177/1043454212452791. [ Links ]

16. Maunder K. Investigating Supportive Care Needs of Parents of Children with Cancer: Is a parent support group intervention a feasible solution. 2012. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bit-stream/1807/33444/3/Maunder_Kristen_M_20121lMSc_thesis.pdf. (10 August 2015). [ Links ]

17. Fletcher PC, Schneider MA, and Harry RJ. How Do I Cope? Factors Affecting Mothers' Abilities to Cope With Pediatric Cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 2010; 27, 266-275. DOI:10.1177/1043454210364623. [ Links ]

18. Björk M, Nordström B, and Hallström I. Needs of Young Children With Cancer During Their Initial Hospitalization: An Observational Study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 2006; 23(4): 210-219. [ Links ]

19. Zeanah CH, Berlin LJ, and Boris NW. Practitioner Review: Clinical applications of attachment theory and research for infants and young children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2011; 52(8):819-833. DOI: 10.1111/j.l469-7610.2011.02399. [ Links ]

20. Christiansen, C. and Townsend, E. Introduction to Occupation: the Art and Science of Living. Pearson Education, 2010. [ Links ]

21. Angström-Brännström C, Norberg A, Strandberg G, Söderberg A, and Dahlqvist V Parents> Experiences of What Comforts Them When Their Child is Suffering From Cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 2010; 27: 266-275. [ Links ]

22. Chaplin, K. The Ubuntu spirit in African Communities. No date. <http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/cultureheritage/culture/Cities/Publica-tion/BookCoE20-Chaplin.pdf.> (12 August 2014). [ Links ]

23. Du Preez R. An ethnographic study of caregiving at a day care centre for developmentally challenged children. Unpublished Dissertation. University of South Africa. 2010. <http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/l0500/4685/dissertation_depreez_r.pdf?s equence=l> (21 August 2015). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Deshini Naidoo

naidoodes@ukzn.ac.za