Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.46 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a6

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

A qualitative exploration of the characteristics and practices of interdisciplinary collaboration

Maria WestI; Kobie BoshoffII; Hugh StewartIII

IOccupational Therapy Honours Student, International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia

IIBOT (UP), B Sc Psych (Hons) (UNISA), MA (AAC) (UP), PhD (UP). Senior Lecturer: Occupational Therapy Programme, International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia

IIIM App SC OT, B Ed, B App Sc OT (University of South Australia). Programme Director: Occupational Therapy Programme, International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia

ABSTRACT

The Children's Centres in South Australia are examples of settings requiring the effective collaboration of disciplines from diverse backgrounds, such as staff from education, health and welfare. Working together across different professional groups is complex and challenging. Existing literature describing collaboration in early childhood settings focuses on exploring the concept from a single professional perspective, with limited exploration from multiple professional perspectives. The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics and practices of collaboration in well-established Children's Centre teams from multiple professional perspectives. It is anticipated that this description can result in strategies for other teams in similar interdisciplinary settings.

A systematic review was conducted summarising the literature on the characteristics and practices of collaboration in Children's Centres, followed by a descriptive qualitative study. Team members from two centres participated in focus groups, thematic analysis was undertaken and findings of both phases were integrated.

Characteristics and practices that support constructive teamwork were identified, with the central theme of leadership and the interrelated sub-themes including: development of team cohesiveness; supportive team processes, as well as working within and between government departments. The study contributes to the understanding of the complexity and inter-relatedness of the characteristics and processes involved in collaboration, highlighting the importance of leaders in supporting the collaboration of disciplines from different professional backgrounds.

Key words: collaboration, teamwork, Children's Centres, qualitative, early childhood

INTRODUCTION

Providing integrated services by a variety of professionals such as from the fields of health, education and welfare, is a growing trend in children's services internationall1,2. In South Australia, such an example is the Children's Centres for Early Childhood Development and Parenting, referred to as Children's Centres. These centres are funded by the state Department for Education and Child Development.

In Children's Centres, multi-disciplinary teams work within an educational paradigm addressing families' health, education and welfare needs. An integrated service approach aims to provide an early intervention focus to support the child within the family, resulting in increased support for families, decreased vulnerability and better outcomes for childrenI,2,3. The centres are generally located in areas where a high percentage of children are considered vulnerable and where families report a lack of access to many services3. Some of these vulnerabilities include children at risk of developmental delays; children with disabilities; children and families from indigenous or multi-cultural backgrounds and those under guardianship of the Minister4. Similar settings occur internationally for example, in England the Sure Start Children's Centres, Toronto First Duty Sites in Canada and Early Head Start and Head Start, in the USA.

Providing a range of services integrated into a single setting and within a collaborative service framework is considered an effective service delivery model for complex and vulnerable population groups3. The team members at the South Australian Children's Centres vary depending on determined needs of the community. Each centre has a Community Development Coordinator and a Director. Other team members may include a Family Services Coordinator (with a focus on child welfare), Allied Health staff (occupational therapists and speech pathologists), as well as Child and Family Health nurses, Education staff and Childcare workers3, amongst others5. The team members may come from different agencies. An inter-agency agreement exists for Allied Health staff, employed by the Department of Health, to deliver a tailored Children's Centre Programme. The Department for Education and Child Development is responsible for the operational management of each Children Centre site.

Collaboration involves different professionals working together to improve outcomes for clients. Collaboration in health care is defined as "the process in which different professional groups work together to positively impact health care" 6:2. Findings from studies within a combined health and education setting suggest that collaboration is considered desirable and necessary for successful client outcomes7,8,9. The importance of collaborative practice in teams with health professionals can be linked to the association shown between good collaboration and increased patient satisfac-tionI0, staff satisfactionII, clinical outcomesI0 including perceived effectiveness of practice11, and greater patient outcomes10,12. Good collaborative practice is however difficult to achieve across Health and Education settings9. Whilst literature regarding collaborative practice related to health settings is available, less is known about collaboration spanning across different organisations and professions such as health, education and other professions.

Primary research on understanding the characteristics and practices related to this new and innovative setting within Children's Centres in South Australia is limited, especially in regards to teams that work across a variety of disciplines in these centres. The purpose of this research project was to provide a description of collaboration in these centres, specifically in regards to characteristics and practices of well-established teams from multiple discipline viewpoints. It was anticipated that an increased understanding will enable the development of strategies for teams in similar settings.

METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted in two phases: Phase 1 comprised of a systematic review to explore the documented characteristics and practices of collaboration in Children Centres and similar teams. In Phase 2, a qualitative descriptive approach was employed to gain a rich description of the topic of interest and to enable an understanding through the experience of the participants13,14. In this case, the rich description relates to the team members' experiences at South Australian Children's Centres. Focus groups are commonly used in descriptive qualitative research15 and were chosen due to the opportunities they provide for the collection of a vast range of information, as well as to gain the collective group perspective16 from team members' multiple viewpoints.

Phase 1: Systematic review

The search terms for the review included:

✥ Inter-professional collaboration, interdisciplinary, intra-disci-plinary, teamwork, collaboration, cooperation, interagency, agency cooperation, integrated services

✥ Children's Centres or Sure Start, or Toronto First Duty Site, or Head Start

The following data bases were searched: Medline, AMED, EMBASE, Academic Search, Premier, CINAHL, Education Research Complete, ERIC, Health Business Elite, Health Source

- Consumer Edition, Health Source - Nursing/Academic Edition, PsycARTICLES, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, PsycINFO, Research Starters

- Education, Web of Knowledge (Web of science and current contents), Science Direct, Cochrane Library and Scopus.

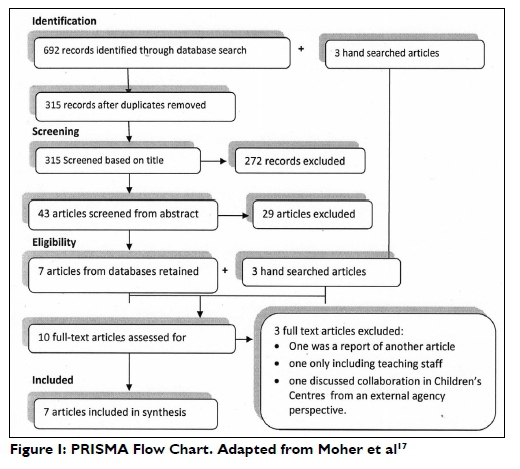

Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA Flow Chart17 to illustrate the search results and selection process. Inclusion criteria for articles were as follows:

✥ Peer-reviewed journal articles

✥ A description of practices and/or characteristics of collaboration or team working at the centres

✥ In English

✥ Obtainable through the University of South Australia library

✥ Included staff working at either a Children's Centre; Toronto First Duty site, Sure Start site or Head Start site

✥ Had at least one Allied Health staff member as part of the team (to capture diversity in professional groups)

The selection and critical appraisals were conducted by two independent reviewers. During the critical appraisals, the McMaster University Critical Review Forms18 were utilized as well as the three items recommended by Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths et al.19 for mixed methods research designs. Full agreement for both selection and critical appraisals were reached. Seven publications were included in this review. Data extraction was performed by the first author with review by the other authors.

Phase 2: Focus groups

Sampling and Recruitment

Purposive sampling20 was used, with specific inclusion criteria utilized to identify the centre teams. In order to enable information to be gained from interdisciplinary teams, Allied Health staff needed to be part of the team, in combination with any of the other disciplines. The team therefore had to include at least one Allied Health member (occupational therapist or speech language pathologist). In addition, in order to ensure that experiences are gained from well-established teams, 50 percent of the team members must have been working at the centre for longer than 12 months.

The Allied Health Programme Coordinator purposefully selected two sites that met these criteria. Individual team members were invited to participate in the study by the Allied Health Programme Coordinator. Participants indicated their informed consent to the researcher, who had an independent relationship with the potential participants. The University of South Australia provided ethical approval for this study.

Descriptions of Participating Teams

Two teams participated in this research, each had four team members. One additional team member could not attend the focus groups and chose to provide responses in written form. The composition of the teams varied, but combined were comprised of the following disciplines: occupational therapy, speech language pathology, education, welfare, community development and nursing.

The duration of staff working at the sites ranged from six months to five years, with the majority working there for two to three years. Both centres were in low socio-economic areas. Statistics show that 20 percent to 23 percent of children attending the sites were considered vulnerable in one or more developmental domains21.

Data Collection

The framework provided by the Office of Education and Practice (OIEP)22 was utilised to develop the focus group questions - see Appendix I. The domains of the OIEP were created to provide guidance to steer education in healthcare teams.

The domains included mission and goals; relationships; leadership; role responsibilities and autonomy; communication; decision-making and conflict management; community linkages and coordination; perceived effectiveness and patient involve-ment22:191.

A pilot focus group was initially conducted at a centre site not included in the main study, to test questions and group procedures, and subsequent changes were made to ensure that data were collected in line with the research aims.

The focus groups were conducted at the site location. Data were audio recorded for transcription and thematic analysis. Each focus group took between one to two hours. In both of the focus groups, the primary researcher led the group, with another researcher present to act as moderator and assistant. Field notes were taken during the focus group, to document observations such as team members' non-verbal behaviour during the focus group.

Data Analysis and Procedures

A verbatim transcription of the audio data from each site was pro-duced14,20,23. The field notes and observations were added to the transcription24. Thematic analysis was used to analyse data, which involved identifying themes and patterns from the data23.

Analysis was completed in sequential stages, as suggested in the literature24. Each transcript was read twice. From the second reading, notes or memos were written in the margin, consistent with guidance from literature24,25 using line-by-line coding24, staying as true to the original data as possible and allowing for themes and categories to emerge23. Reflective practice was adopted26, particularly being mindful not to assume categories24. A second researcher analysed the data independently. Both researchers discussed themes and full agreement was reached. An audit of decisions made was kept. A summary of the themes and categories was prepared and distributed to the sites for member checking. The transcripts and summary documents were compared for similarities and to determine the final themes.

In the final analytical process, results from both the systematic review and focus groups were combined and integrated.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Systematic review

Seven studies met the selection criteria and were included in the review, all from Children's Centres in the UK. The seven studies provided relevant background information and stated a clear purpose, provided in-depth discussion of the findings, made relevant conclusions and contributed appropriately to this review. The results of the critical appraisals indicated that the studies provided limited information relating to the context of each site discussed, for example the cultural population groups of each centre, the socio-economic status and how long the centres have been in existence. In considering the context, the UK centres are similar to the South Australian centres, in that they have been set up in locations considered to experience socio-economic disadvantage.

Four themes emerged from the data extraction and are provided in Table 1, namely: organisational aspects, working relationships, internal processes and working with external agencies.

Phase 2: Focus groups

The teams provided a rich description of characteristics and practices utilised by them. An overarching theme was identified: leadership that supports collaborative practice. This central theme was supported by three sub-themes: development of a cohesive team, supportive team processes and working within and across government departments.

Leadership that supports collaboration

Participants noted that leadership is important for facilitating constructive collaboration. The following quote highlights the influence of leadership: If you've got positive work culture from leadership down, most people will pick up on that. This theme was central to the other sub-themes, since leadership was described as playing a significant supporting role in enabling the other characteristics and processes to occur.

Development of a cohesive team

One team described themselves as a cohesive team, with personalities that want to work together and are committed to building the team. This cohesiveness was evident in the discussion with frequent laughing, gentle banter and supportive comments. This team also identified that they are flexible in sharing and learning from each other and value and respect each other's contributions, including not overstepping boundaries. The teams articulated the characteristics of having a shared belief system, shared framework of understanding and shared purpose. The purpose was articulated as working together to provide support to children and families in their local communities. The following quotes provide examples:

And the beauty of our team, is that we all have our specialised areas that we all work within and all bring that to make the whole.

We really value each other's contributions and if we are not sure we all feel comfortable to go and speak to whomever in their role and we ... share that information within a framework of shared understandings which I think makes us very strong in what we do.

Supportive team processes and structures

Processes discussed by the teams which facilitate team work include: building relationships within the team, informal discussion, meetings and team planning, building relationships with external agencies and families, referral processes and conflict resolution.

Building relationships within the team

The teams emphasised how important trusting relationships and good communication are for effective teamwork. The following quotes illustrate the theme:

A lot of communication is about the relationships you build.

I think a really important part of that is being present face to face to establish those relationships because of course, we have other ways of communicating as well by email and phone and so on, but until you have those relationships, you can't have effective communication.

A challenge mentioned is where some staff, like Allied Health staff, spread their time between more than one Children Centre site, thus limiting their availability at each site. This impacts on the practices of building relationships as those team members have less time to collaborate within the team. Additionally, working across various sites means those team members need to adjust to working within multiple teams. The following quote highlights this: . working part time across different sites, different processes, different cultures, walking into a different workplace every day.

Some examples of practices used to build relationships, include: informally sharing ideas and advice, running groups together, sharing the care and promoting the services to others together. In some instances, team members engage in joint visits to give different professional perspectives. One site discussed having occasional social events, such as lunches to bring everyone together. Whilst these are not done on a large scale, the team reports we do enough to keep the team feeling cohesive. Learning through team training days were emphasised as being valuable at one site.

Informal communication

Both sites recognised that most of their team's communication happened on an informal basis. Informal discussion as a practice provides opportunity for information sharing, generating and sharing ideas, planning, inviting team member participation and relationship building. These tend to occur when trust and respect is there and when team members are open to engage in discussion. This is illustrated by the following quote:

I think most people are open to new ideas at the site. Like in having conversations with people about new programs and things like that -people are open to having a discussion.

Physical space is an important consideration for informal discussion. Debriefing sessions at one site occur regularly, particularly on the couch, over coffee. The open plan structure of both sites creates opportunity for team member discussion and collaboration on an informal basis. However both sites suggested that the separation of buildings between the Children's Centre and the preschool created a sense of division. Informal discussion tends to happen throughout the day and can be a way to overcome some of the separation.

Whilst it is recognised that team members cannot be interrupted whilst engaged in running groups, the lunchroom is recognised as an effective space for informal discussion. The following quote illustrates this point:

We do get to talk around the table in the lunchroom and everyone's got fairly good relationships in the centre so we do talk between ourselves and you know make it a, everyone makes it priority to know what's going on.

Having staff available for informal discussion can be a challenge. One site suggested that whilst the lunchroom was opportune for catching up, it was difficult if team members were not on a break at the same time, or where staff members' hours do not permit a break.

Meetings and team planning

Meetings are common practice of both sites. One example is site meetings that provide a platform for team members to get together, share ideas, create plans and discuss happenings at the site. One site discussed having fortnightly Case Review meetings, providing opportunity for team members to case manage clients. All meetings characteristically tend to be casual rather than formally structured.

However, whilst meetings are noted as valuable and give you a lot of energy to keep going again, both sites highlighted that the challenge of meetings relates to time and availability. Coordinating timetables is challenging, with competing appointments. Allied Health staff members tend to be part-time and are required to work across a number different sites, according to their employment requirements. This arrangement is different for Allied Health staff compared to most other professions in the centres. Allied Health staff therefore may not make it to scheduled meetings. Consequently team planning, idea sharing and contributions from all team members in meetings are limited. A further challenge suggested by one site is sharing information from meetings with all team members. Formal processes such as minutes have been attempted, but prove difficult to get going.

Team members have an expectation to be at their own professional meetings. Whilst this provides an opportunity for planning and information sharing, a complication for the Allied Health staff members is that they are not allocated time for these sessions. Therefore, the time is often taken from the limited days they have at the site. This impacts on team collaboration. As one team member pointed out:

Probably does feel a bit unfair for these teams at times cos I'm not around in that late afternoon time sometimes where some of that collaboration about future programs and current programs does happen.

Building relationships with external agencies and connecting families

Collaboration and building of relationships with external agencies is an ongoing practice for Children Centre teams, where the relationship can benefit clients. One site suggested that their good reputation with external agencies resulted from the good relationships, which had been built:

It comes back to relationships, I think we are very fortunate here that we have a good reputation from other agencies about the staff here and . care that the children get and the professionals that work here. So people are keen to be a part of our centre.

Some of the examples of collaborative activities with external agencies include external agency run programmes, playgroups or holiday programmes at the centre, which may also include volunteers or support from non-government organisations. Part of dealing with external agencies occurs in the practice of partnership group meetings, which may include representatives from various agencies, community organisations and members from other Children's Centre sites.

Building relationships with families is fundamental for site success. As suggested at one site: It's about relationships you build to support families. One way of building these relationships, as mentioned by participants is through parent/carer input into the term calendar. Parental involvement assists to ensure programmes reflect the needs of children or families. Building relationships also involves reaching and maintaining connections with vulnerable families and connecting them with appropriate services.

Referrals

Children's Centre referrals commonly occur both internally and externally. One team acknowledged that their referral practices work well, due to team members being knowledgeable about the services available and sharing the information with others.

Team members use processes such as completing written applications for referrals. The referral process may however start with an informal process first before continuing on to a more formal process. This informal process may depend on the availability of staff members to discuss the referral or the preferred working style of the team member.

The centre is sometimes a starting point for families. Team members may frequently refer to each other and can provide direction and referral for additional services. For example, the Allied Health staff may refer children/families for specific therapy either through General Medical Practitioner centres, privately operated services or government funded disability organisations. Some referrals to external agencies may require team collaboration, particularly around terminology and therefore team members may assist each other with form completion.

Conflict resolution

Conflict resolution processes are in place. Firstly, team members are encouraged to talk to the person concerned, and then if the conflict continues, managers are called upon. A difficulty with the latter aspect is that team member managers are not located within the site and therefore may not understand the dynamics of the conflict. One site mentioned additional strategies for addressing conflict, include debriefing and seeking ongoing peer support from own professional groups and informally chatting with other team members.

Working within and between government departments

The last theme relates to a key characteristic and some challenges impacting on teams, identified by participants within the theme of "working within and between government departments".

Participants identified the ability to work within the framework provided by an individual team member's own employing department, whilst fitting in with the other team members' departments' cultures. One example given was related to leadership. Leadership comes from a variety of sources. For Allied Health staff, this includes leaders from an educational background, as well as leaders from a health background. Differences in leaders' backgrounds and priorities, can create challenges for team members to deal with. Site management is provided by leaders from an educational background, thus shaping the culture of the site. Team members from other backgrounds, need to fit in with this educational focus, whilst simultaneously following the guidance from their own department.

Other examples provided revolved around perceived differences and inequalities between agencies in regards to priorities in spending of consumables and services budgets, which can create conflict in teams. Professional accreditation requirements was mentioned, as an example, where one profession may have a specific requirement related to hygienic procedures to be followed and the use of related consumables, which may incur extra costs for a site. If the requirement is not an accreditation aspect of team members from other departments, it may not be given the priority that it needs and may become a challenge for the team to deal with.

Integrated results of Phases 1 and 2

The results from the systematic review and focus groups were combined (displayed in Table 1) and integrated (displayed in Figure 2). The table illustrates how the focus group results support and extend the review results and show the inter-relatedness of the characteristics and practices. The focus groups conducted in the South Australian Children Centres highlight the important overarching influence of leadership to support collaborative practice and illustrate the themes of working within and between government departments, as well as conflict management.

DISCUSSION

This study has provided a description of the complexity and inter-relatedness of characteristics and practices involved in the collaboration in well-established Children's Centre teams.

The significant role of leaders was highlighted and emerged as central theme in this current study. Coleman, Sharp and Hand-scomb27 identified in their study the leader behaviours of highly performing Children Centres in the UK. Our characteristics and practices of collaborative practice in South Australian Children Centre teams are encapsulated by a number of the leadership behaviours mentioned by Coleman, Sharp and Handscomb27 namely: having a clear and shared vision; facilitating open communication and embracing integrated practice (which includes use of common team processes).

The development of team cohesiveness has been identified as a characteristic of collaborative practice in centres and is supported in literature focussing on health-education teams. Authors such as Boshoff and Stewart28, articulated the need of Children Centre teams to develop as an identity in itself, consisting of the sum of the different team members involved. These authors emphasise the need for commitment of all team members to the team. The current study identified the need for a shared purpose and framework of understanding. Coleman, Sharp and Handscomb27:13 in their study found that effective Children Centre leaders "pro-actively championed constructive and inclusive approaches to integrated working within teams from a range of professional backgrounds". These leaders actively strived towards building high levels of trust amongst different professionals. They recognised variations in professional backgrounds and culture and worked to overcome related barriers. Approaches used by leaders included building shared understandings, appreciating each other's cultures, pressures, challenges and priorities.

The review illustrates that studies from the UK Children Centres indicate that success is dependent on a variety of leadership styles, including efficient and inspiring leadership29 and leaders who are aware of team emotions and the impact of those on the centre30. A study by Bagley, Ackerley and Rattray31:601 highlighted a "non-hierarchical approach" which was successfully adopted by a manager and showed respect for the different views and problem solving ideas of team members. Leader mentoring is suggested by John32, as being useful to address some of the challenges of working in the UK Children's Centres.

Effective leadership is mentioned by Coleman, Sharp and Handscomb27 as fundamentally premised on strong interpersonal relationships. Building of relationships is in turn dependent on effective communication and underpins collaborative practice. These aspects were mentioned in this study. The review found that working relationships are key to successful collaboration. Children Centre authors from the review27,29,31,33,34 mention formal operational processes like joint team meetings and shared professional development opportunities to promote greater understanding between professionals. However, given the difficulties with time and staff availability, team planning and idea sharing through meetings are limited and consequently, information sharing occurs informally as well. Similar difficulties are discussed in the UK Children Centre literature, with challenges in organising meetings around staff who work on a part-time basis29. Coleman, Sharp and Handscomb27 found that effective Children Centre leaders used a key strategy to promote partnerships by pro-actively sharing resources, space and equipment or encouraging co-location of services to support service delivery at the centre.

In the review, variation exists in relation to meeting processes, with one study suggesting no formal processes exist for roles taken on by members during the meeting, or minute/record keeping34. A similar experience exists in this study with one site suggesting minute taking had been attempted but proved difficult to implement. Another article highlights the importance of documentation to formalise meetings, including taking minutes of the discussion, priorities, decisions and outcomes30.

Another practice highlighted in the focus groups and supported by the review is referrals from internal and external sources. In the focus groups, one team identified that their referral processes worked well and in addition, both formal and informal types of referral occur, with team members supporting each other in making appropriate referrals. In the review, studies from the UK found differing ideas on the referral process and its success, for example Nelson, Tabberer and Chrisp describe the referral process - as "a highly skilled process - however can often involve delays in time, which can affect timely service provision"35 (p. 303). For other settings, special processes such a uniform Referral and Allocation Processes (RAP) have been implemented to assist sites to refer appropriately and develop clear accountability33,34. According to Morrow, Malin and Jennings34, appropriate referral requires innovation beyond conventional understanding of roles. Additionally, these authors suggest that periodically the referrals should be discussed to ensure any interventions that have been implemented are successful. According to Nelson, Tabberer and Chrisp35 this periodic discussion did not tend to commonly occur. In addition, working with external agencies as part of the team, can involve difficulties such as lack of understanding by external staff of services provided by Children Centres.

The impact of limitations of space and staff availability for collaborative practice has arisen both in this study and in other literature relating to similar types of settings. In the focus groups, team members discussed how their open-plan sites invite collaborative practice. However the separation of the centre building from the preschool, impacts general team work with all early learning staff and in addition, Allied Health staff spread their time across various sites. One study in the UK Children Centre literature suggests that being physically located in the one building allowed for increased informal discussion and expansion of working relationships36; however, another study suggests that co-location of professionals does not always equate to effective working29. Therefore, experiences are mixed and suggest that success is possible for both scenarios and depends on the complex interplay of other team-specific characteristics.

Examples of challenges related to successfully working within and across government departments have been illustrated in the focus groups and provide new understandings of the complexities of working across sectors within South Australian Children Centres. These sites are operationally managed by the Department of Education and Child Development, from which local site leadership, protocols and culture stem. Staff from varying disciplinary backgrounds may be employed by various departments including education, health and welfare. Team members need to juggle the requirements and protocols of their own departments, whilst conforming and adapting to the site culture and requirements. Similarly, a UK study on working in Children's Centres reported an outreach worker advising "everybody is employed through somebody different making partnership working difficult"37:606. Coleman, Sharp and Handscomb27 found that effective leaders of Children Centres worked on a strategic level with managers from other services as well as on an operational level to support the coordinated delivery of services at the centre.

Organisational aspects were identified in the review, including examples such as working towards shared targets and outcomes (between departments), processes for information sharing, professional co-location in the same building and leadership. Professional co-location has been identified in the focus groups and is discussed elsewhere. In the focus groups examples were discussed by teams: differing funding priorities, related to processes and sources, as well as differences in employment arrangements, such as some professional groups requiring to work across multiple sites.

Differing funding priorities and sources is a similar theme to the experiences from Children Centres in the UK, as illustrated by the review. It is said that the funding structure can cause anxiety for practitioners who are concerned about long-term sustainability and which in turn can hamper collaboration38. In a study by Atkinson et al.39 focussing on multi-agency working and involving education, social services and health sectors, a key factor for success of multi-agency working was identified as sharing and access to funding and resources. Their study found that sharing of funding and resources was a common challenge. Their recommended strategies were pooled budgets, joint funding and identification of alternative or additional sources of income. A leader from a UK Children's Centre mentioned that funding was not there to cover time spent at meetings nor the resultant paperwork40. Additionally, these authors state that health visitors were frequently understaffed, making partnership arrangements unreliable.

Participants in this study discussed the impact of different employment arrangements between team members, depending on the employing government department and varying acts under which staff from different disciplines are employed. This finding highlights an important aspect which seems to not have been explicitly mentioned in other literature before. The example of Allied Health team members was provided, typically working across more than one site and thus within multiple teams. These arrangements have the follow-on effect that these team members have less time for building relationships and have limited availability at each site. They also need to adjust to working within a number of teams. These arrangements are in contrast to other team members, who are located only at a single site.

These challenges are evident in other Children Centre literature, for example Malin and Morrow33 in the review, mentioned conflict in teams, which can occur when team members work towards targets that differ between governments. Lewis, Roberts and Finnegan37 mention the challenges of different line accountability as well as terms of conditions of employment. Again, Coleman, Sharp and Handscomb27 mention the critical role of leaders in creating a shared vision, supporting integrated working and having open and honest discussion with partners in facilitating collaborative practice.

Limitations and Recommendations

This study has increased the knowledge of the characteristics and practices of two well-established South Australian Children Centre teams. The review was limited to a search on journal articles, but other sources of information, for example from books, reports and unpublished sources, may further expand the picture of collaborative practice. The review was limited by uncovering only UK articles.

Focus groups were an ideal method to gain the collective experience of the group, whilst providing the opportunity to witness each team's collaboration. Interviews with individual team members will add a different perspective to the information gained in focus groups. In addition, exploring the challenges faced by less well established teams, would uncover additional understandings of the complexities faced by team members. A limitation of this study was that both sites were metropolitan. Team members from rural sites may articulate different characteristics, practices and challenges. Further research incorporating additional sites including rural locations may increase transferability.

It is anticipated that the information obtained through this study will be transferrable to other similar sites where collaboration occurs across disciplines and organisations. The importance of enabling leadership to facilitate collaborative practice is a key recommendation from this research. Mentoring and professional development support for leaders are strategies to strengthen leadership in Children Centres and similar settings.

CONCLUSION

During this study, multiple team members' perspectives were obtained, of the characteristics and practices of collaboration in well-established South Australian Children Centre teams. The findings of the focus groups support and extend the review conducted. The overarching and instrumental theme of leadership is supported by the following themes: development of team cohesive-ness, supportive team processes, and working within and across government departments. The themes illustrate the complexity and inter-relatedness of these characteristics when working within teams that span health, education and other disciplines.

REFERENCES

1. Nichols, S. & Jurvansuu, S. Partnership in integrated early childhood services: an analysis of policy framings in education and human services. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 2008; 9: 117-130. [ Links ]

2. Nolan, A, Cartmel, J. & Macfarlane, K. Thinking about practice in integrated children's services: considering transdisciplinarity. Children Australia, 2012; 37: 94-99. [ Links ]

3. White, L. "The virtual village: raising a child in the new millennium" Department of Education and Children's Services. 2005. http://ecsinquiry.sa.gov.au/ (20 July 2012). [ Links ]

4. Boshoff, K. & Grimmer-Somers, K. The International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, Interim Evaluation Report: Allied Health in Children Centre's Program, University of South Australia, SA Health and Department of Education and Child Development, South Australia, 2012. [ Links ]

5. Government of South Australia. "Children's Centre Staff". 2011. http://www.childrenscentres.sa.gov.au/pages/CC/CCs/?reFlag=I. (1 May 2013). [ Links ]

6. Zwarenstein, M, Goldman, J. & Reeves, S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes", Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2009; 3: CD000072. [ Links ]

7. Edwards A. Relational agency in collaborations for the well-being of children and young people. Journal of Children's Services, 2009; 4: 33-43. [ Links ]

8. Hillier, S, Civetta, L. & Pridham, L. A systematic review of collaborative models for health and education professionals working in school settings and implications for training. Education for Health, 2010; 23: 1-12. [ Links ]

9. Kennedy, S. & Stewart, H. Collaboration with teachers: A survey of South Australian occupational therapists' perceptions and experiences. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2012; 59: 147-155. [ Links ]

10. Grumbach, K, & Bodenheimer, T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2004; 291(10): 1246-1251. [ Links ]

11. Lemieux-Charles, L, & McGuire, WL. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 2006; 63(3): 263-300. [ Links ]

12. Bower, P, Campell, S, & Bojke, C. Team structure, team climate and the quality of care in primary care: An observational study. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 2003; 12: 273-279. [ Links ]

13. Hanley-Maxwell, C, Al Hano, I. & Skivington, M. Qualitative research in rehabilitation counselling. Rehabilitation Counselling Bulletin, 2007; 50: 99-110. [ Links ]

14. Magilvy, JK & Thomas, E. A first qualitative project: qualitative descriptive design for novice researchers. Journal for Specialists in Paediatric Nursing, 2009; 4: 298-300. [ Links ]

15. Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 2000; 23: 334-340. [ Links ]

16. Kidd, PS & Marshall, MB. Getting the Focus and the Group: Enhancing Analytical Rigor in Focus Group Research. Qualitative Health Research, 2000; 10: 293-308. [ Links ]

17. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, & Altman, DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 2009; 6: e10000. [ Links ]

18. Letts, L, Wilkins, S, Law, M, Stewart D, Bosch, J. & Westmorland, M. Critical Review Form. McMaster University, 2007. [ Links ]

19. Pluye, P, Gagnon, M, Griffiths, F. & Johnson-Lafleur, J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2009; 46: 529-546. [ Links ]

20. DePoy, E. & Gitlin, LN. Introduction to research: understanding and applying multiple strategies. Missouri, USA: Elsevier, 2011. [ Links ]

21. Commonwealth of Australia. Australian Early Development Index 2012; http://maps.aedi.org.au. (15 October 2013). [ Links ]

22. Schroder, C, Medves, J, Paterson, P Byrnes, V Chapman, C, O'Riordan, A, Pichora, D, Kelly, C. Development and pilot testing of the collaborative practice assessment tool. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2011; 25: 189-195. [ Links ]

23. Liamputtong, P. Qualitative data analysis: conceptual and practical considerations. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 2009; 20: 133- 139. [ Links ]

24. Casey, MA & Krueger, RA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: SAGE Publications, 2000. [ Links ]

25. Charmaz, K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: SAGE Publications, 2006. [ Links ]

26. Finlay, L. Reflexivity: an essential component for all research? The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1998; 61: 453-456. [ Links ]

27. Coleman, A, Sharp, C, Handscomb, G. Leading Highly Performing Children's Centres: Supporting the Development of the 'Accidental Leaders'. Educational management administration and leadership, 2015; 1-19. [ Links ]

28. Boshoff, K. & Stewart, H. Key principles for confronting the challenges of collaboration in educational settings. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2013; 60: 144-147. [ Links ]

29. Cottle, M. Understanding and achieving quality in Sure Start Children's Centres: practitioners' perspectives. International Journal of Early Years Education, 2011; 19: 249-265. [ Links ]

30. Smith, P & Bryan, K. Participatory Evaluation: Navigating the Emotions of Partnerships. Journal of Social Work Practice, 2005; 19: 195-2009. [ Links ]

31. Bagley, C, Ackerley, C. & Rattray, J. Documents and debates Social exclusion, sure start and organisational social capital: evaluating inter-disciplinary multi-agency working in an education and health work program. Journal of Education Policy, 2004; 19: 595-607. [ Links ]

32. John, K. Sustaining the leaders of children's centres: the role of leadership mentoring. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 2008; 16: 53-66. [ Links ]

33. Malin, N. & Morrow, G. Models of interprofessional working within a Sure Start "Trailblazer" Programme. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2007; 21: 445-457. [ Links ]

34. Morrow, G, Malin, M, Jennings, T. Interprofessional teamworking for child and family referral in a Sure Start local programme. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2005; 19: 93-101. [ Links ]

35. Nelson, P Tabberer, S. & Chrisp, T. Integrated working in Children's Centres: A User Pathway Analysis. Practice: Social Work in Action, 2011; 23: 37-41. [ Links ]

36. Lewis, J, Roberts, J. & Finnegan, C. Making the transition from Sure Start Local Programmes to Children Centres, 2003-2008. Journal of Social Policy, 2010; 40(3): 595-612. [ Links ]

37. Bachman, M, O'Brien, M, Husbands, C, Shreeve, A, Jones, N, Watson, J, Reading, R, Thoburn, J, Mugford, M. & National evaluation of Children's Trusts Team. Integrating children's services in England: National Evaluation of Children's Trust. Child: care, health and development, 2008; 35: 257-265. [ Links ]

38. Atkinson, M, Wilkin, A, Stott, A, Doherty, P Kinder, K. Multi-agency working: a detailed study. Berkshire: Local Government Association, 2002. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kobie Boshoff

Kobie.boshoff@unisa.edu.au