Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.46 no.3 Pretoria Dez. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a2

COMMENTARIES

Patricia Ann de Witt

Dip OT (Pret), MSc (Wits), PhD (Wits). Head, Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Theraputic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Wits University

ABSTRACT

This paper explores the ethical concerns which were identified in a mixed methods study to determine the facilitators and barriers to quality clinical education on the clinical training platform of the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits).

Ethical and professional behaviour concerns were extracted and analysed from focus groups and questionnaires that were used to collect data for the study. The ethical and professional behaviour concerns and responsibilities are discussed in terms of the clinical educators in their role as both clinicians and educators. Ethical and professional concerns and responsibilities are also highlighted in respect of students in their role as developing learners and professionals. How students learn ethical and professional behaviour is discussed as well as how a clinical educator should encourage these important clinical competencies which students tend to learn in an overt rather than covert manner. The paper also considers how in a service delivery placement where the focus is on clients' right to care, and the students' right to education may be overlooked and their professional learning compromised. The importance of a sound clinical educator-student relationship is central to professional education and facilitation of reflective practice and clinical reasoning essential for the learning of ethical and professional behaviour.

Key words: Clinical education, ethics, professional conduct

INTRODUCTION

According to the Health Professional Council of South Africa (HPC-SA) all occupational therapy students are required to complete a minimum of 1000 hours of clinical work under the supervision of a qualified occupational therapist1. The HPCSA Minimum Standards of Training for Occupational Therapists indicate that the nature and extent of clinical supervision varies as students gain experience. Students from first to third year are required to work under the direct supervision of a registered occupational therapist, while final year students need only to work under guidance1. While there is no clear definition of the specific difference between direct supervision and guidance, it is clear that all students have to be guided/supervised, either directly or indirectly, as they transition their classroom knowledge and skill to the occupational therapy process for clients in any service delivery setting.

There is agreement within the occupational therapy profession, that the nature and quality of the guidance/supervision provided in the context of professional education, is not only critical to the student's learning process but also has important implications for the development and future of the profession2-5. While much has been reported in the literature on the clinical education process6, the clinical educator's role and responsibilities7, clinical educator's preparedness4,5,8, and the benefits and challenges of clinical educa-tion9,10, very little has been published about the ethical responsibilities and issues associated with clinical education in occupational therapy. In the context of this paper the term 'clinical education' has been favoured over the term 'clinical supervision' as literature suggests the clinical or professional supervision is a process of professional development appropriate to qualified professionals while clinical education is the process of learning that applies to students as they gain clinical competencies from clinical experience11-13.

While all occupational therapy students have instruction on legislation, ethics, professional conduct and etiquette embedded in their theoretical curriculum, competence in every day ethics is gained in the clinical context1. Ethical and professional behaviour in the context of clinical education brings together a complex interaction between legislation and professional ethics associated with client care and the teaching and learning of a developing profes-sional14. The literature reports that ambiguity exists as to how an occupational therapy student's ethical competencies are developed and as a result the responsibilities and expected outcomes for both the clinical educator and student are ill-defined15. This is due to ethical standards, reasoning and behaviours often being covert and understood rather than spoken about. This results in ethical learning developing through professional socialising and role modelling, rather than as a considered, reflective cognitive process16-18. To facilitate a student's ethical learning requires the clinical educator be aware of, explicitly identifying and discussing ethical related issues as a routine part of client centred discussion and clinical teaching19. The importance of this was highlighted in a study by Hyrkas and Paunonen-Ilmonen20 who found that long term ethical competence and quality of care, is positively influenced by the nature of clinical education students receive.

This paper considers the ethical concerns which were raised in a study, completed within the Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), to determine various barriers and facilitators to clinical education. The study did not explore the ethical issues associated with clinical education per se, but issues relating to ethical and professional behaviour in the clinical education context were raised as a concern in many parts of the study. Thus this paper does not report on a specific study but gives a commentary on ethics and professional behaviour as it may impact on the clinical education process of students. This paper does not imply that unethical and unprofessional behaviour is wide-spread in our clinical training contexts, but that it is an element of professional education that requires more attention as competence in ethical practice and professional behaviour is an outcome of occupational therapy education.

Since every interaction between a student and a client demands ethical and clinical decision making, consideration of the client's rights and needs, and the clinical site's health and service delivery policies, resources and costing structures19 in the context in which the clinical education takes place, need to be understood and the implications for patient care overtly discussed. While clinical staff are best placed to inform students of the factors that might affect the rehabilitation of patients, deciding on who is in the best position to discuss the ethical implications of premature discharge due to medical funds being exhausted or pressure on beds or who is responsible or accountable when there is no splinting material, gloves, bandages, bedding and even food, is far less clear. Students are often not privy to service delivery issues that impact on the ethical and professional care of patients particularly those that are intrinsically tied to political, financial and management issues, so it makes service limitations difficult to understand from a professional and ethical point of view. When students work in departments for an extended period of time they sometimes also become aware of professional practice, leadership and management incompetency's which are known and never spoken about. It is not clear how this should be dealt with in the context of professional education.

In the context of the Wits occupational therapy programme, clinical education is embedded in the curriculum at strategic points to link the theory to practice. Clinical work is introduced in first year but increases in time over the four years so that the final year could be considered a clinical year. All students complete the following blocks varying from a total of four to nine weeks in each of the following fields of practice: mental health, physical, paediatrics (learning disabilities and cerebral palsy) and public health in a community site (urban and rural). In this clinical placement, students work under the guidance of an on-site occupational therapist who is also the clinical educator.

The Wits occupational therapy clinical training platform includes some 44 clinical education sites in four provinces of South Africa. These sites are used more or less exclusively by Wits occupational therapy students. The profile of the on-site clinical educators developed during the time of the study indicated that approximately 48 to 55 qualified occupational therapists were involved in the clinical education of Wits students. Eighty five percent were between 20 and 30 years of age and the majority had had less than 3 years of clinical experience. Fifty five percent of these clinicians classified themselves as novice or advanced beginners in their professional development as clinical educators based on Brenner's five stages of development21,22. Over 55% of these clinicians did not really want to take on the clinical educator role but did so as it was part of the job, although 95% of them felt it was their professional responsibility. Most felt they derived some personal benefits from involvement in clinical education. These benefits included keeping up to date (93%), receiving continuing education units (CEUs) (69%) needing to retain their registration with HPCSA and being exposed to new ideas (85%). Clinical educators also felt that there were some service benefits that the students provided, including being an extra pair of hands in the occupational therapy departments and that they could be assigned to do the jobs that clinical staff does not have time to do. The students were also able to give clients more individual attention.

METHODOLOGY

The study that raised the concerns around ethics and professional behaviour in clinical education was a large exploratory sequential mixed method study designed to examine the clinical education of final year occupational therapy students on the Wits clinical training platform. In keeping with the exploratory mixed methods design the data collection started with focus groups of all the clinical education stakeholders: 4th year occupational therapy students, on-site clinical educators and university staff. This was followed by two quantitative studies where on-site clinical educators and department managers also completed a questionnaire pertaining to training in clinical education, support for clinical education as well as the perceived challenges and benefits attached to the fulfilment of this role.

As described above the purpose of this paper is not to report on the study but to describe some the ethical concerns raised by the all participants, which have been extracted and analysed. The roles of both the on-site clinical educators, as clinician and teacher, and the student as a developing professional and learner in clinical education, were considered. The legal and ethical practice as well as professional behaviour and etiquette associated with the teaching and learning domain and clinical domain will be discussed in relation to these roles. While the exclusion of the voice of the university educator may be a limitation to this paper this will be discussed in a subsequent article.

The purpose of this report was not to criticise but to stimulate some professional debate around the role of a clinical occupational therapist as a clinical educator which creates an additional dimension to ethical behaviour, ethical dilemmas and professionalism in occupational therapy.

REVIEW OF THE LEGAL AND ETHICAL PRACTICE IN CLINICAL EDUCATION

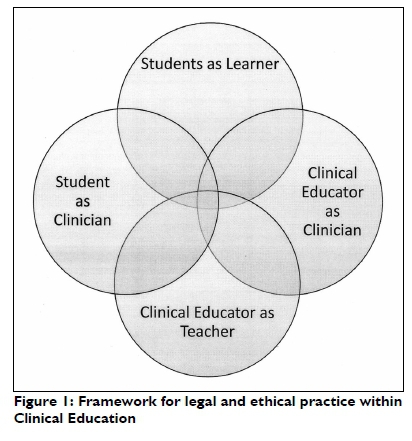

A review of the literature on clinical education was conducted. Ethical and professional concerns in clinical education are reflected in Figure 1 which depicts the interdependent roles of the clinical educator and the student in clinical education.

CLINICAL EDUCATOR AS A CLINICIAN

Ethical practice is central to service delivery excellence by all health practitioners including occupational therapists. Ethical practice is guided by a complex and sometimes difficult decision making process which is based on professional judgement in keeping with a complex legislative and professional ethical framework within countries14. Professional judgement involves observing, thinking, reflecting, interpreting, arguing and evaluating the best intervention options available, appropriate and acceptable to the client, his care givers and his context in keeping with the law, ethical principles, the service provider resources and policies. Such decisions must be rational, defensible, properly recorded and wherever possible based on best evidence 6,18,23,24. Clinical decision making using professional judgement has been described as crucial to professional autonomy14,24, and has been shown to mature with experience and the development of expertise. Novice therapists tend to use mainly informative factors and reflection-on-action to inform their clinical decision making while experienced therapists tend to use more directive factors which allows for more reflection-in-action-resulting in more immediate decision making24. As most of the clinical educators on the Wits clinical training platform can be considered novice therapists, this lack of maturity in clinical decision making and professional judgement may be reflected in the role modelling of professional ethical behaviour which is what students observe and become as the example of appropriate ethical and professional behaviour.

Professional and moral values are demonstrated by the manner in which occupational therapists demonstrate a passion for the profession25 and approach their working context. These values are also reflected in their relationships, concern for the clients and their caregivers and co-operation and collaboration with team members through their professional behaviour and professional etiquette18,23. Legal and ethical knowledge is practically demonstrated through their understanding and consideration of the client's right to an appropriate and equitable occupational therapy service, understanding of policies and regulations related to health care provision relative to the context and how this influences the therapeutic relationship and decisions around appropriate occupational therapy interven-tion26. Ethical practice includes daily practice of the universal ethical principles: informing clients of their intervention options and respecting their right to critical, honest information about their condition and their treatment so they can make an informed decision about their health and their health care needs (autonomy and veracity); gaining of informed consent; practicing confidentiality and protecting clients' personal information (confidentiality); working within the professional scope and referring to others when appropriate; doing the very best for clients under all circumstances (beneficence); ensuring all clients have equal access to treatment resources (distributive justice) keeping acceptable client records; billing appropriately; not over-servicing but advocating for additional services should the client need these23,27.

Legal and ethical behaviour is demonstrated in the occupational therapy process by completing accurate assessments that identify the occupation-based needs and deficits of the client in such a way that appropriate intervention can be planned and executed. Intervention must be relevant to the client and his context, respect his values, cultural beliefs and practices, occupational profile and values (respect), aim to do good, protect the client from harm (beneficence), not to deliberately cause harm to the client (non-malificence) and fulfil the client's need for service equitably (duty and justice)6,18,28.

It was clear from the participants in the study that a number of legal/ ethical issues related to clinical practice are of concern in the settings where clinical education takes place. The occupational therapists working in the private and public sector reported facing ethical dilemmas on a daily basis. These ethical dilemmas often depended on the manner in which they generate an income.

Private sector occupational therapists, like other health professionals, were reported experiencing conflicts regarding their earning capacity versus client's occupational therapy needs which raised ethical dilemmas. Common concerns raised related to overcharging, over-servicing and sometimes unprofessional and anti-competitive behaviour to secure a sufficiently large and consistent client base 28.

Occupational therapists in the public sector - where earnings are secure - experienced other ethical dilemmas such as over-involvement in administrative tasks and meetings, so that little time is available to provide services. Choosing not to treat clients or putting off treating clients in favour of other activities of a more personal nature such completing academic assignments that have limited relevance to the workplace, playing computer games, and even nail-care and shopping were reported. Other issues raised included; early and unexpected discharge where the client is discharged without prior warning, resulting in no plan having been made for the client to receive essential rehabilitation on the primary care platform or for the client to return for follow up. Concerns related to limited availability of essential resources such as standardised tests, assistive devices and wheelchairs as well as expendable materials, tools and equipment to engage in occupation-based interventions were also noted. The non-compliance of clients with intervention regimes such as splinting and home programmes and non-return for follow up is also affecting service delivery negatively; resulting in frustration, failure to achieve desired treatment outcomes and sometimes punitive action such as making them wait an unaccept-ably long time before getting attention or sending a patient away for missing or being late for an appointment.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that there are also some clinicians that do not always practice within the scope of the profession and therefore the therapy provided was not professionally appropriate, difficult to distinguish from physiotherapy and psychology and hard to recognise as occupational therapy. The fact that clinicians were reported to seldom have the time or access to the resources to seek evidence to support their practice, resulting in out-of-date practices was also raised and has been supported by some professional literature29.

Students are acutely aware of these issues in the clinical settings. If these issues are not discussed openly, and the professional behaviour and the clinical decision making overtly challenged, students draw conclusions from their own experience and assumptions about what is or is not appropriate professional behaviour. Students are observed to sometimes either simply copy the professional behaviour that they see, accepting powerlessness and assuming that this is just how it is (right or wrong) or they become uneasy and sometimes hypercritical when they observe behaviour that is contrary to what they believe is acceptable professional practice. They are often uncertain as to what action they should take and what the consequences might be (considering their 'vulnerable' position as students).

CLINICAL EDUCATOR AS A TEACHER

The important role that clinical educators play in the development of an occupational therapy student's professional and clinical skills cannot be over emphasised as this has implications that extend far beyond their student years30.

In South Africa, unlike some countries in the occupational therapy world, there is no formal or accredited training for clinical educators and therapists with only six months experience are often called upon to supervise students4,6. The majority of clinical educators at the clinical training sites on the Wits training platform are young and inexperienced occupational therapy clinicians. In addition they are ill-prepared for the educational role they take on when they are still in the novice stage of developing their own professional behaviour and ethical practice in dealing with ethical dilemmas. The clinical reasoning and decision making that informs professional behaviours is complex and is seldom overt.

Role modelling accompanied by reflective discussions has been reported as the best method of teaching professional ethical behaviour and reasoning. However to do this, clinical educators need to reflect on their own personal and professional values and beliefs and then review how these influence and are enacted in their daily work. In addition they should reflect on the legal and ethical factors that impact on professional and clinical decision making and these reflections should form the basis of discussion and teaching of students18. These reflections should be used to support and guide the students' developing perception of the realities of practice, which sometimes challenge their ideals.

Clinical reasoning and reflective practice is needed to provide the clients with the best available intervention in the light of contextual constraints and limitations/challenges, and the students with the best clinical education and learning opportunities31.

Thus it is easier for clinical educators, especially those that lack experience, to assist students to use their theoretical learning to make sense of practical clinical skills - such as how to help a client to transfer - more easily than making sense of ethically based clinical reasoning, that informs professional and ethical behaviour7.

Research by Carrese et al.19 found that clinical educators seldom addressed ethical issues with students. These researchers postulated that reasons why clinical educators did not explicitly discuss professional and ethical clinical reasoning with students was related to time pressures; that they felt these issues were obvious to the student; that the clinical educators did not recognise these issues as relevant or immediately associated with client management; and that clinical educators were ill-prepared for this kind of teaching19. However, professional behaviour and ethical practice is always evident to students through the professional behaviours that they observe and they draw independent conclusions about clinical practice without guided reflection and sometimes take a very narrow view of professional behaviour and ethical dilemmas without taking all the contextual or more macro issues into account.

Clinical educators are also reported to act as gatekeepers for the profession and have a responsibility to ensure that the students they supervise have an acceptable level of professional behaviour, clinical competencies, and ethical clinical reasoning and decision making6. Clinical educators are expected to guide the students and their expectations should be consistent with the students' level of professional development. Different models can be used to understand what can be expected of the student such as the Stages of Ego Development described by Loevinger where Stages 3/4 (Explorer) and Stage 4 (Achiever) have been associated with senior students' level of clinical reasoning32.

Clinical educators also need to consider that students as learners have legal and moral rights while completing a fieldwork block which is considered an essential part of an education programme. These include the right to supervision/guidance appropriate to their level of clinical competence to ensure safe and effect service provision and to avoid harm or breach of the professional standards6. They have the right to due process which describes making the student aware of professional and educational expectations within the setting. These include clinical site policies/procedures for administration of professional services such as billing and recording of therapy units, use of expendable materials, recording of patient information and organisational policies that influence intervention times. Students also need to understand reporting lines, clinical education and evaluation activities and times; policies around critical incidents such as a client falling or being injured and needle-stick or other injuries to staff and students6.

While some students reported outstanding clinical education opportunities and experiences, other students felt that their clinical learning had been compromised by complex clinical educator-student relationships and contexts that did not support the teaching and learning process. Some students reported situations where occupational therapists demonstrated what they believed to be inappropriate ethical and professional behaviour as clinical educators by evaluating/marking clinical learning activities that were not observed, not providing timely feedback on clinical performance or opportunities to learn, as well as giving feedback that students perceived as being personally demeaning and disrespectful.

Therefore it is evident that not all clinical educators are aware that students believe they are entitled to respect and to the answering of their clinical questions in a way that assists them to understand concepts and in solving complex problems. Students report that they are especially sensitive to be given feedback about their performance in front of clients or other students and in a manner which is unconstructive to their learning process. Students believe they have a right to being treated equitably and fairly with respect in feedback and evaluations, should not be compared to other students, be evaluated in accordance with their level of development and not be expected to know what the clinical educator knows or thinks they should be able to do. University departments have some responsibility for ensuring that clinical educators are aware of the clinical learning that is required and how this clinical learning is supported by the classroom teaching. This is especially true when classroom teaching includes new professional terminology and practices that is innovative and is supported by new evidence. The university's responsibility may also extend to providing clinical educators with some educational knowledge and skills to facilitate student teaching and learning.

The position of the students should not be abused by assigning tasks outside of the professional scope, that are punitive and that the qualified staff would not or do not wish to do. Students also find it difficult to deal with clinical educator criticisms of what they have been taught in previous blocks and by the university staff. In keeping with the fidelity principle and collegial relationships, clinical educators should discuss such issues with the persons concerned rather than the student. The right to confidentiality - especially about students' educational challenges and any personal problems which they may reveal - also needs to be adhered to and disclosed with consent of the student to identified persons only.

STUDENT AS A LEARNER

While basic education is determined as fundamental right in term of Chapter 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, the Bill of Rights, tertiary education is considered to be more of a privilege than a right26. However students pay for their tertiary education, some more directly than others, but they all have some expectation that they will receive a quality education both in the classroom and in the clinical setting. While a student can hold the university accountable for the quality of the classroom education, accountability for clinical teaching is much less straightforward as the Memoranda of Understanding that oversee the provincial responsibility for clinical education in the public sector training sites are vague and difficult to enforce.

Although the Wits occupational therapy department has longstanding and co-operative relationships with all sites on the Wits clinical teaching platform, reports from students of challenges related to their clinical education have been increasing in number over the past 10 years. A survey completed by two consecutive final year student cohorts identified almost identical challenges with regards their clinical education in the clinical education sites: Limited availability of the clinical educator and therefore a lack of clinical education opportunities; concerns about evaluation and how marks were derived, as well as the fairness and consistency of the evaluation processes; negative attitudes towards the students which had some negative gender and racial overtones and the inexperience of many clinical educators with students perceiving that there was nobody to learn from. Finally a lack of professionalism by the clinical educators was raised as a challenge 50% of the respondents: Students reported this to be clinical educators' attitude to the profession, practicing outside of the 'scope', work ethic issues, out of date practice, poorly managed departments and unprofessional behavior.

While challenges have been noted (especially in relation to the staff profiles as reported above, staff shortages, resource constraints and service delivery pressures), clinical education remains essential so as to develop an appropriate human resource pipeline for the profession. It is evident that occupational therapy students can only gain clinical competencies in a clinical setting and on-site occupational therapists are best placed to facilitate this process.

Thus it would seem reasonable that if a clinical site accepts students to complete their clinical education, then a student could expect that there will be a qualified occupational therapist to direct the clinical education of junior students or guide the clinical education of senior students1. On a practical and moral level this implies that students could expect the clinical educator to be clinically competent, understand her clinical educator role and carry out the responsibilities associated with this role. These include ascertaining the strengths and limitations of the student's current clinical skills and their clinical learning needs that have to be facilitated in order to meet the clinical block (placement period) outcomes6.

Students could also reasonably expect a conducive clinical learning environment and that appropriate clinical learning opportunities will be planned33. An appropriate clinical educator -student relationship should be formed as central to the clinical education process and the clinical educator should role model professional, ethical behaviour and best practice. Student's can also expect that reasonable but designated time will be made available to direct the clinical learning to assist them in developing appropriate clinical skills through discussion and observing and not just from the marking of written reports. It is expected that they should also be provided with fair, equitable, appropriate and timely formative and summative feedback and that their performance will be evaluated and marks recorded in the designated manner6,34.

Occupational therapy students on the other hand are adults and are responsible for their learning. In order to transition their classroom learning into practice they need to have reasonable grasp of the theory and if they are aware that this is not the case then it is the ethical responsibility of the student - towards the clinical educator as well as to any client they might assess or treat - to plan and implement some action to remedy this35.

Clinicians reported problems with some students not being adequately prepared when arriving to treat patients, having inadequate theoretical knowledge, being unable to manage their time in terms of meeting written requirements and copying other students' work. It is clear that the ethical responsibility also extends to academic honesty. A study by Rozmus and Carlin28 reports an increase in student cheating and dishonesty through the use of technology which includes a disregard for confidentiality, plagiarism, and cutting and pasting of other student's work. Whether this is a time management strategy or an action to support a struggling peer, it is nonetheless unethical and will have consequences if identified.

Thus in order to learn, students must plan, allocate and manage time to actively engage with the learning opportunities, to perhaps not be so focused on the written tasks associated with learning but be open to clinical opportunities that will extend their professional development. However, permanent and effective learning requires students to critically reflect on their professional knowledge, skills and values, identify the gaps and use a self-directed approach to master the required knowledge, seeking help and support when necessary31.

STUDENT AS A CLINICIAN

In order for an occupational therapy student to learn clinical competencies they must participate in and apply the occupational therapy process, both individual and group, to real live clients and in so doing become a 'clinician under the direction' of a qualified occupational therapist1,36. This requires that a student is ethically answerable to the qualified occupational therapist, who is ultimately and vicariously responsible for client care and service provision, on any issue related to the care of that client(s). Students - just like qualified staff - have a duty of care and if this is not met then they may be found to be negligent. Thus, the student is accountable for all actions and omissions and responsible to report to the clinical educator on any aspect of the occupational therapy process in a manner which has been negotiated and is appropriate to the student's level of clinical expertise. The clinical educator is responsible for approving the appropriateness of therapeutic occupations and for guiding the student's therapeutic intentions related to the client in his current and future context. Failure to provide this supervision will hamper the student's learning but more seriously, the clinical educator could be held liable if the student's intervention causes harm if appropriate supervision had not be effected6.

Since this is a learning situation the level of clinical competency expected from students must be consistent with the university prescribed educational outcomes for the specific clinical block and the level of the student's experience. When working under direction the students should organise that their clinical performance be observed, evaluated and that they must be given formative feedback so as to understand both their clinical strengths and weaknesses.

Where clinical skills are found to be weak, these must be identified by the clinical educator for the student, especially if their insight is poor. A programme of remediation must be planned by the clinical educator and student in consultation with the university staff so that appropriate multi-dimensional learning opportunities can be provided where students are able to practice clinical skills within the clinical context with supportive instruction and feedback while encouraging reflection-on action12,31.

Research by Carres et al.19 reported on specific ethical dilemmas that students experienced as learners during clinical work. These included: recognising the limitations of their knowledge and skill and concerns that this limitation impacted negatively on being able to provide quality service to clients. They also felt that the temporary nature of their contribution raised concerns about commitment, and were concerned about the termination of the relationship with the client and responsibility for care for the patient once they left. This same research identified ethical dilemmas in health system care provision which students feel powerless to deal with: such issues as the finances that control the treatment a client can have based on their financial resources; availability of resources such as transport to health care centres, drugs and equipment availability. Time and health care providers' schedules which limit availability of services due to meetings and other responsibilities, were also of concern19.

These same concerns were echoed by the students and clinicians that participated in the focus groups in this current research. Participants reported observing a lack of ethical and professional behaviour in some settings where clients were sent away when they were late for appointments or because the therapist wanted to leave early. There were also reports of clinical staff playing games on computers or cellular phones during working hours, interrupting therapy by taking personal calls on cellular phones; failing to treat clients appropriately and working outside the scope of practice. While participants acknowledged that there were centres of excellence, the incidents that they observed and had perceived to be unethical, even if they were irregular occurrences, were concerning and create troubling dilemmas for students as learners.

Critical review of all professional behaviour, both their own and that of others, is essential to professional learning. This review is the responsibility of clinical educators as well as academic staff. Helping students reflect on moral and ethical professional behaviour is as important as enabling students to voice their concerns about incidences that they perceive to be unethical. Discussion about what is 'moral' and 'just' versus 'ethical' and 'unethical' in the context of professional practice provides rich learning opportunities which help students to consider professional behaviour holistically as well as the reasons behind professional behaviour and the context within which they are taken.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this paper was to highlight and discuss the ethical responsibilities that clinical occupational therapists and students take on in the clinical education context. In addition the paper proposes to raise the awareness of how clinical educators can assist occupational therapy students to engage with ethical and professional behaviour issues in the clinical context so as to become critically thinking and reflective practitioners.

REFERENCES

1. Health Profesions Council of South Africa Professional Board for Occupational Therapy Medical Orthotists and Prosthotists and Art Therapy. Minimum Standards of Training for Occupational Therapists. 2010. [ Links ]

2. Bester J, Beukes S. Assuring Quality in Clinical Education. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2011; 41(3): 30-4. [ Links ]

3. Committee on University Fieldwork Education. Canadian Guidelines for Fieldwork Education in Occupational Therapy (CGFEOT). Association of Canadian Occupational Therapy University Programs, 2003 2011. Report No: 2003 revised to 2011, v2011r. [ Links ]

4. Costa D. Fieldwork Issues: Fieldwork Educator Readiness. Bethesda: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2007. [ Links ]

5. Kirke P Layton N, Sim J. Informing Fieldwork Design: Key elements to quality in fieldwork education for undergraduate occupational therapy students. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2007; 54: S13-S22. [ Links ]

6. Costa D. Clinical Supervision in Occupational Therapy: A Guide for Fieldwork and Practice. I ed. Bethesda: American Occupational Therapy, Inc., 2007. [ Links ]

7. Best D. Exploring the Role of the Clinical Educator. In: Rose M, Best D, editors. Transforming Practice through Clinical Education, Professional Supervision and Mentoring. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Elsvier Churchill Livingstone; 2005: 45-8. [ Links ]

8. Cross V From Clinical Supervisor to Clinical Educator: Too much to ask? Physiotherapy, 1994; 80(9): 609-61. [ Links ]

9. Queensland Occupational Therapy Fieldwork Collaborative. "Benefits of OT Supervision". 2007. <http:www.qotfc.edu.au/clinical/index.html?page=64668&pid=0> (28.07 2010) [ Links ]

10. Thomas Y, Dickson D, Broadbridge J, Hopper L, Hawkins R Mc Bryde K. Benefits and Challenges of Supervising Occupational Therapy Fieldwork Students: Supervisors' Perspective. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2007; 54: S2-S12. [ Links ]

11. Asia Pacific Occupational Therapy Congress. "Supervision as profesional development". 2007. <http://occupationaltherapyotago.wordpress.com/2007/07/03/supervision-as-profession> (28.7.2010 2010) [ Links ]

12. Clouder L, Sellars J. Reflective Practice and Clinical Supervision: an Interprofessional Perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2004; 46(3): 262-9. [ Links ]

13. Fish D. The Antomy of Educational Evaluation in Clinical Education, Mentoring and Professional Supervision. In: Rose M, Best D, editors. Transforming Practice through Clinical Education, Professional Supervision and Mentoring. Edinburgh: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone: 2005: 1-369. [ Links ]

14. van der Reyden D. Legislation for Everyday Occupational Therapy Practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2010; 40(3): 27-35. [ Links ]

15. Henderson A, Tyler S. Facilitating Learning in Clinical Practice: Evaluation of a Trial of a Supervisor of Clinical Education role. Nurse Education in Practice, 2011; 11: 288-92. [ Links ]

16. Brunger F Duke PS. The Evolution of Integration: Innovations in Clinical Skills and Ethics in first year medicine. Medical Teacher, 2012; 34: e452-e8. [ Links ]

17. Franklin C, Vesely B, White L, Mantie-Kozlowski A, Franklin C. Audiology: Student Perception of Preceptor and Fellow Student Ethics. Journal of Allied Health, 2014; 43(1): 45-50. [ Links ]

18. Brown L. Ethics in Clinical Education. In: Rose M, Best D, editors. Transforming Practice through: Clinical Education,Professional Supervision and Mentoring. Ist ed. Edinburgh: Elsivier Churchill Livingstone; 2005: 1-369. [ Links ]

19. Carres JA, Mc Donald EL, Moon M, Taylor HA, Khaira K, Beach MC, et al. Everyday Ethics in Internal Medicine Resident Clinic: An opportunity to teach. Medical Education, 2011; 45(7): 712-21. [ Links ]

20. Hyrkas K, Paunonen-Ilmonen M. The Effects of Clinical Supervision on the Quality of Care: Examining the results of Team Supervision. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2001; 33(4): 492-502. [ Links ]

21. Brenner P From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. American Journal of Nursing, 1984; 84(12): 1479. [ Links ]

22. Aiken F Menaker L, Barsky L. Fieldwork Education: The future of Occupational Therapy depends on it. Occupational Therapy International, 2001; 8(2): 86-95. [ Links ]

23. Hunt MR, Ells C. A Patient-centered Care Ethics Analysis Model for Rehabilitation. American Model of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitaion, 2013; 92(9): 818-27. [ Links ]

24. Wainwright SF, Shepard KF, Harman LB, Stephens J. Factors that influence the Clinical Decision Making of Novice and Experienced Physical Therapists. Journal of Physical Therapy, 2011; 91(1): 87-101. [ Links ]

25. Spurr S, Bally J, Ferguson L. A Framework for Clinical Teaching: A Passion-centred Philosophy. Nurse Education in Practice, 2010; 10: 349-54. [ Links ]

26. Constitution: Chapter 2 Bill of Rights, S. Chapter 2(1996). [ Links ]

27. Association AOT. Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2015; 69(Supplement 3): 1-10. [ Links ]

28. Rozmus C, Carlin N. Ethics and Professionalism in a Health Science Center: Assessment Findings from a Mixed Methods Student Survey. Medical Science Educator, 2013; 23(3S): 502-12. [ Links ]

29. Lyons C, Brown T, Hui Tseng M, Casey J, Mc Donald R. Evidence-based Practice and Research Utilisation: Perceived Research Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Barriers among Australian Paediatric Occupational Therapists. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2011; 58: 178-86. [ Links ]

30. Crowe MJ, Mackenzie L. The influence of fieldwork on the preferred future practice areas of final year occupational therapy students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2002; 49(1): 25-36. [ Links ]

31. Baird M, Winter J. Reflection, Practice and Clinical Education. In: Rose M, Best D, editors. Transforming Practice through Clinical Education, Professional Supervision and Mentoring. First ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005: 1-369. [ Links ]

32. Schwartz KB. An Approach to Supervision of Students on Fieldwork. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1984; 38(6): 393-7. [ Links ]

33. Brown L, Kennedy-Jones M. Part 2 The Manager Role. In: Rose M, Best D, editors. Transforming Practice Through Clinical Education, Professional Supervision and Mentoring. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone Elsvier; 2005: 1-369. [ Links ]

34. Marriott J, Galbraith K. Part 3 Instructor, Observer and Provider of Feedback. In: Rose M, Best D, editors. Transforming Practice through Clinical Education, Professional Supervision and Mentoring. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone Elsivier; 2005: 1-369. [ Links ]

35. Alsop A, Ryan S. Taking Responsibility. In: Allsop A, Ryan S, editors. Making the Most of Fieldwork Education. London: Chapman and Hall; 1996: 1-243. [ Links ]

36. Hocking C, Ness N. Revised Minimum Standards for the Education of Occupational Therapists. World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2002. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Patricia Ann de Witt

patricia.dewitt@wits.ac.za