Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.46 n.2 Pretoria Aug. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n2a8

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Shaped by place: Environmental influences on the participation of young cyclists from disadvantaged communities in professional cycling

Suzanne StarkI; Theresa LorenzoII; Susan Landman BOT (US) MSc OT (UCT)

IBOT (US), MScOT (UCT). Occupational Therapist, Carpe Diem School, George

IIBSc OT (WITS), Higher Diploma for Educator of Adults (WITS), MSc Community Disability Studies (University of London), PhD Public Health (UCT). Professor, Disability Studies, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: The Cycling Club provides opportunities for young cyclists from disadvantaged communities to participate in cycling on a professional level. Little literature exists that explores the potential role of occupational therapy in the field of professional sport. This qualitative study explored the influence that environmental factors had on the experience of participation of professional cyclists from disadvantaged communities.

METHOD: A collective case study design was applied using photovoice and unstructured interviews as methods of data generation with three of the professional cyclists. Other sources of data generation included a focus group held with the team and a key informant interview held with the team coach.

RESULTS: The findings present themes from each participant's unique story reflecting the environmental influences on their experience of participation in cycling. It also includes themes from the team coach's perspective on the structure of cycling teams and team dynamics

DISCUSSION: This section draws on a cross case analysis of the findings which is contextualised through the application of the International Classification of Function's list of environmental factors. Environmental factors discussed are products and technology; the natural environment; appreciating supportive relationships and attitudes and the relevance of services, systems and policies.

CONCLUSION: This study offers a fresh perspective from conventional sporting interventions by focussing on the influence of the environment on sporting performance rather than attempting to improve sporting performance. It is evident that the significance of the environment should be considered more carefully by coaching staff as it could ultimately improve performance of cyclists who come from disadvantaged communities. Taking an occupational perspective, this article highlights the potential contribution of occupational therapy in the field of professional cycling.

Key words: Cycling, environment, International Classification of Function, participation, youth

INTRODUCTION

The Cape Town Cycle Tour is the largest individually timed race in the world. This popular race runs the distance of 110 kilometres along the scenic landscape of the Cape Peninsula and attracts approximately 35 000 cyclists every year. As a spectator or participant in a cycling event of this magnitude one becomes aware that cycling is an elite sport, with participation reserved for those who can afford it. Based in Cape Town, the Cycling Cluba, a Not for Profit Organisation, attempts to bridge this problem through the promotion of cycling in South Africa's poorest communities. Within the South African context disadvantaged communities refer to racial groups disadvantaged during the Apartheid regime (including black, coloured, indian and chinese people)1. The Cycling Club presents five programmes with the top two focussing on competitive cycling participation. These two top programmes provide sponsorships to participants, equipping cyclists with a bicycle, clothing, nutritional supplements and access to specialist sports facilities and services. The Cycling Club's elite team is one of the top two teams focussing on competitive cycling and was the focus of this study. This team functions under the guidance of a programme manager who works closely with the team coach to facilitate optimal sporting performance through specialist assessment, intervention and training programmes. The authors are not affiliated or employed by the Cycling Club and had no involvement with the Club other than conducting research with the elite team.

The contribution of occupational therapy to the world of competitive sport centres mainly on the participation of persons with disabilities. Hardly any literature exists that explores the potential role or contribution of occupational therapy to the field of competitive sport. The dearth of literature comes as a surprise when considering the definition of occupation as the "ordinary and extraordinary things that people do every day"2, with sport being a crucial part of so many peoples' everyday activities. Taking an occupational perspective, it has been proposed that occupational engagement in meaningful occupations can contribute to the development of people as individuals and members of society3. In this study, cycling is framed as the occupation to be explored. Theory on the transformative potential of occupation is well established, but would it hold true when applied to cycling? Could cycling serve as a vehicle through which youth could realise and utilise their potential, transform their lives, pursue their aims and overcome barriers, as suggested by Watson and Fourie3? Participation in occupation, has been described as the "mechanism for the maintenance and growth of physical, mental and social capabilities' central to health"4. Hammell5 similarly proposes that one of the fundamental contributions that occupation makes in daily life is the creation of meaning. She argues that: "Engagement in personally meaningful occupations contributes, not solely to perceptions of competence, capability and value, but to the quality of life itself" 5.

When considering participation in cycling, what are the influences impacting on the experience of participation and, ultimately, cycling performance? Coming from a disadvantaged background, what role does the environment play in the participation of youths in cycling? Therefore in order to address these questions the aim of the study was to describe the role of the environment on the experiences of participation in cycling. The objectives identify how the environment served as a barrier or facilitator to participation in cycling.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sport and its potential contribution

Sport is increasingly being utilised as a tool through which people can learn skills and principles thereby contributing to the holistic development of young people particularly6. Coalter describes the most significant impact of sport programmes as "the development of individual and collective potential"729. Listing the development of individuals and communities, he describes the possible contribution of sport to the following outcomes: improved self-esteem, self-confidence and social skills; commitment to education; reduced social isolation; increased sense of trust, co-operation and communal responsibility and the development of leadership skills and future aspirations. These potential benefits, however, remain a mere possibility as it cannot be assumed that all or any participants will automatically acquire these benefits in all circumstances8. Some outcomes remain only a possibility due to the significance of the parallel social influences and developmental processes that take place as part of normal life. Furthermore, it cannot be assumed that competencies gained will be transferred to the wider social or community environment. According to Coalter8, sport "is not a priori good or bad, but has the potential of producing both positive and negative outcomes"8.

Sport in South Africa

According to the Department of Sport and Recreation South Africa (SRSA)9, sport participation remains skewed and generally low with only 30% of the population participating in sport and poorer communities generally being excluded. Mashishi10, former president of South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (SASCOC) comments that, despite of obtaining democracy in 1994, South Africa has "yet to dismantle the legacy of apartheid inequality, disparity and underdevelopment in sport"10. He acknowledges that appropriate facilities and holistic support to athletes are the factors most lacking in our sports. The need for the sporting community to give attention to the holistic development of athletes over their life span has been advocated. There is a need to nurture athletes as "valuable human resources" to avoid the "social death" experienced by so many athletes upon retirement11.

Youth

In South Africa, it is the children and young people who suffer most severely from the prevailing challenging socio-economic conditions12. Mokwena13 remarks that Steve Biko's words are as applicable today as they were in the 1980s: "Township life alone makes it a miracle for anyone to live up to adulthood"13.

Recent empirical evidence demonstrates that youth living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods had poorer developmental outcomes and greater exposure to unhealthy activities and lifestyles14.

Youth development has been described as a "process that allows young people to acquire the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will enable them to become self-sufficient individuals who can contribute positively to their own communities and to society as a whole"12. This approach is based on the inherent belief that young people are human resources who have the capacity to contribute to all spheres of society. Foley12 recommends that youth organisations need to create spaces and structures for young people to reflect on their experiences and voice their perceptions on life.

The role of context

Consideration of the role of the environment on people and their occupations is relevant to occupational therapy and has received increased attention from occupational therapists in recent years15. The profession of occupational therapy now rightfully acknowledges the role of the environment as a means of intervention16. Shaw17highlighted the importance of understanding place and how place underscores occupational participation. It is well established that "the importance of context has long been acknowledged as key to occupational engagement"3.

Of significance to this study is the impact of context on participation in professional cycling for youth who come from disadvantaged communities within the South African context. According to the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) contextual factors encompass the entire background of a person's life and living and include environmental and personal factors18. Environmental factors are defined as those aspects that "make up the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives"18. The World Health Organisation advises that an environmental factor can be a barrier because of its presence, but also because of its absence18. With regards to facilitators, one should consider the accessibility of a resource as well as its sustainability and quality.

METHOD

Qualitative research methodology was used as a means to explore the aim of this study. The researcher made use of an interpretative framework as it intends to "study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them"19. A collective case study design was applied as it refers to an enquiry into a number of cases to explore a particular phenomenon20.

The study population consisted of all twelve members of the Cycling Club's professional team. Convenience sampling was used to select three participants through presenting the outline of the research to the professional team members at a weekly team meeting. Three cyclists volunteered to participate in the study. Each participant received a research information sheet and had the opportunity to ask questions prior to providing informed consent.

Data generation

Photovoice, unstructured interviews, a focus group and a key informant interview were used to generate data. Photovoice is a highly flexible participatory approach whereby participants use cameras to capture the reality of their lives19,20. This approach is used with great effect in projects involving youth as it positions them as producers in the research process21. The three participants were requested to reflect on their participation in cycling and to consider whether it has had an influence in their lives. They were then required to take pictures of those things/areas of their lives that they felt had changed through their participation in cycling. Participants were introduced to the technical aspects of using a camera and they each received a disposable camera. The photographs were developed by the researcher. Unstructured interviews were held by the first author with each participant using the photographs as prompts for conversation. Follow up interviews were conducted and concluded when the data reached saturation or yielded no new information22. Of the three individual participants, two chose to be interviewed in Afrikaans and one in English. Interviews were held in a private room at the cyclists' training center and lasted sixty to ninety minutes per interview with two interviews conducted with each participant. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

A focus group was held with all twelve members of the elite team, including the three participants. The question for discussion was kept broad, asking participants to reflect on how cycling has made a difference to their lives. The information yielded in this group gave the researcher an indication as to what extent the experiences of the individual cyclists resonated with that of their team. Following the analysis of the findings it was clear that some of the cyclists were unhappy with the management of the team. It was therefore deemed necessary to also interview the team coach, who acts as the team manager, as a key informant. Patton23 suggests that a key informant is a person who is "particularly knowledgeable about the inquiry setting and articulate about their knowledge - people whose insights can prove particularly useful in helping an observer understand what is happening and why"23.

As a key role player in the decision making of the team, consent was obtained from the team coach to be interviewed. The issues raised by individual cyclists were presented to the team coach who was given an opportunity to voice the team's perspective on these issues.

Data management and analysis

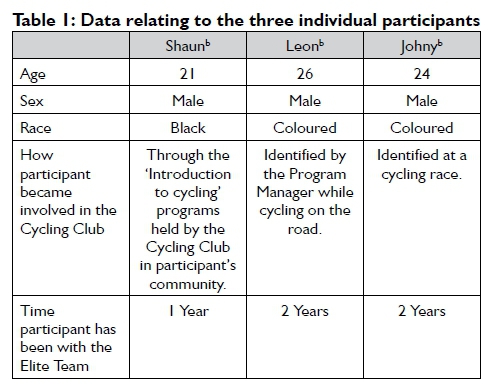

Prior to the analysis of findings, a description of each case was documented to situate the context, background and history of each participant24. The age, sex, social circumstances, living environment and history of how the cyclist became involved in the team are described here (see Table I).

The first author initiated the detailed analysis of the interviews with a coding process, involving a manual process of cutting and pasting the information into chunks based on their meaning24. Chunks were grouped together to form sub-categories which, when grouped together, contributed to categories of meaning. Categories were then grouped together to form themes that represent the findings of the study for each case. After each interview the data were analysed and findings were presented to the participants who confirmed or corrected their relevance as a form of member checking to ensure trustworthiness. Through ongoing data generation and analysis the researcher was able to verify themes, expand on them where necessary, and in some instances, fill the gaps. Creswell25describes the analysis and thematic representation of each case as the within-case analysis. These themes are presented in the results section of this article and describe the role of the environment on the experiences of participation in cycling.

The process was then followed up by a cross-case analysis involving the examination of "themes across cases to discern themes that are common to all cases"25. Following this, deductive analysis of the environmental factors was conducted to guide the discussion in this article, which focussed on how the environment served as barrier or facilitator to participation in cycling. The ICF's subsection of environmental factors was considered a useful tool to conceptualise the latter18. Four of the five categories of environmental factors of the ICF were used to frame the discussion and included products and technology, the natural environment, support and relationships and systems and policies. The fifth category, Attitudes', is included under support and relationships.

Ensuring rigour

Several methods were employed to ensure trustworthiness and rigour. These included triangulation of data sources and member checking with participants by verifying the accuracy of interpretations. To ensure reflexivity during the research process, the researcher kept a reflective journal, which recorded the researcher's internal dialogue and contributed to creating awareness regarding potential biases and assumptions.

Ethics

The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Cape Town granted approval of the research protocol. Informed signed consent was obtained and pseudonyms were given to all participants, the organisation and the institution where cyclists train.

RESULTS

The results section consists of the individual stories of the three participants namely Shaunb, Leonb and Johnyb. The key findings from the focus group are reflected under the group experience and the findings from the coach's perspective are also described. Each individual story as well as the group experience reflect how the environment influences the cyclists' experiences of participation in cycling. The coach's perspective reflects the findings relating to team dynamics.

The profiles of the three participants, Shaun, Leon and Johny, are described in Table I. Within the South African context the term 'Coloured' refers to people of mixed race who have a cultural identity distinct from both that of Black African or White South Africans. The term is generally not considered to be offensive in South Africa26.

Shaun's story

Shaun lives in a township on the outskirts of Cape Town. To facilitate his professional cycling career Shaun had to generate the support of those who play a significant role in his life. He is confident when he speaks about the support he receives from his family. While friends in Shaun's community struggle to understand his different dietary preferences his family expresses their support of his dietary needs (Figure I). Shaun avoids fatty foods and prefers pasta and meat prepared without oil. His family allow him to cook food that he is required to eat, for himself. Another form of support is his relationship with fellow cyclists, which seemed to be based on shared experiences. The Cycling Club enabled Shaun and other cyclists from his community to relocate to a team house in another section of the township where they are free from disturbances.

Prior to living in the team house, Shaun describes the challenges that township life pose to a professional cyclist as well as how he negotiates these challenges which include not resting enough prior to a race as Shaun and his family live next door to a tavern doing business until late at night. Of further concern to Shaun is the threat of his sponsored bicycle being stolen due to the high incidence of crime in the township.

And here are the robbers ... If you wash your bike and you go inside the house and you come out of the house - the bike is gone.

Shaun furthermore feels that his participation in cycling is often the cause of having to face the jealousy of others. According to him there is the perception that, because he is a cyclist, he may have more opportunities afforded to him, which results in deliberate negative behaviour towards him, often in the form of mocking and disrespect from members in his community.

Because what I say is, if they come by next to my house and they ask: 'Hey, wanna come with us?' I say: 'No man, I have to race tomorrow'. They say: 'Oh, ... you'. You know what I'm saying? Sorry for the word. They would like shout at me and say bad things.

Shaun also speaks of a lack of appreciation of what it takes to be a cyclist in his community. From Shaun's perspective it is evident that people's appreciation of a sport is influenced by their exposure to and experience of the sport. A sport more familiar to the community, such as soccer, seems to be regarded as more valuable.

They expect you to play soccer, if you're riding a bike you're wasting your time.

Leon's story

Leon's contract with the professional team was ended during the process of the research as the team coach felt he did not perform to expectations. He has since found employment at a cycling shop in Cape Town.

Leon describes how challenging financial circumstances had taught him self-reliance which enabled him to participate competitively in cycling. He tells how he saved to afford a bike and to pay entry fees for races, which his parents were not able to do. Cycling also provided Leon with the opportunity to escape from conflicting relationships with family members at home.

Following his termination from the professional programme, Leon's feelings of anger and bitterness are tangible in his reflection on the values of the organisation. He feels that preferential treatment is granted to those cyclists who are the best performers and he experienced a sense of powerlessness to speak his mind within the team. He feels that the freedom to voice one's opinion hinged on the condition that one gets good results. Without positive results, he was not in a position to make demands.

If you get results fine, then you can tell them what you want, what you don't agree with. But if you didn't, then just keep quiet.

He mentioned an incident when the star performer of the team, who is notorious for speeding while driving (according to Leon), had an accident with the team's car. Leon felt that, instead of taking it seriously, the team management 'laughed it off.

According to Leon there is racial inequality within the professional team. Two of the three Coloured riders recently lost their contracts and Leon feels the programme caters for Black African riders exclusively. He is of the view that the programme should shift its focus to include riders from disadvantaged communities across the racial spectrum to give a true representation of South Africa's population.

Poverty can be any colour ... South Africa is not just Black, there are other people as well.

To illustrate this point Leon took a picture of informal housing structures where white people are living (Figure 2).

Johny's story

Johny has been a member of the Elite team for two years. One of his highlights during this period was when he was chosen to accompany members of the Cycling Club to attend the Tour de France.

Coming from a disadvantaged background his participation in the Cycling Club's professional team has helped his performance through their provision of a specialised bike, supplements and professional training.

The supplements that you could use, the energy drinks and all those things. I couldn't get such things, I had to survive on sugar water during competitions. And I was able to come off sugar water, I can afford all those things now because the team gets it for me.

The opportunity to attend the Tour de France enabled Johny to meet some of his international role models in cycling and inspired him to improve on his cycling performance with his dream being to one day also participating in the Tour (Figure 3).

Johny emphasises the significance of receiving support from one's family as one of the key contributors to participation in cycling. Another motivator for participation mentioned by Johny was the hardships he endured growing up.

You can say the place where I come from, some call it the ghettos ... So I can say that it is through struggling that I became stronger ... It is something that motivates you ... The circumstances from the past, you don't want to look back to the past. You want to make a better future.

Johny is one of the two Coloured riders whose contract with the Cycling Club's professional team had recently been terminated since the team coach felt he did not perform well enough. By implication he had to hand back his cycling gear and bike and was left without a bike shortly before a big race.

The group experience

The group experience refers to the findings of the focus group. Cyclists often feel they are not taken seriously by their families as cycling is not perceived as a professional career.

You know our parents don't really know how demanding cycling is. If you're always coming up with reasons that you were to go and train, go and race, it's as if you're running away from all the responsibilities.

Members of the group recommended having local cycling races as a way to generate understanding in their communities and families about the demands of cycling. Group members felt that, when people have the opportunity to witness races in their local community, they might gain some understanding of the sacrifices professional cyclists have to make.

The significance of role models was emphasised by cyclists who felt this contributed to their own, and younger cyclists', motivation for continued participation in cycling. Cyclists felt that one of their most important contributions is to be an example to the younger generation. When you are a good role model, you have the ability to help others make the right choices for their lives and be an example of someone who is focussed on achieving their goals.

All I can say is there's nothing more important than being an example to the boys coming from behind, . Because there are still kids like looking up to him, you know, he has to be an example. Not gallivant and doing all these kind of stuff.

A coach's perspective

Jamesc, the team's coach, makes it clear how he sees the structure and working of the team by means of comparing the ranking of team members to generals and troops in the military service. The best rider in the team earns the role of 'the general' and he is able to make requests and give commands to his troops or fellow team members.

Cycling is a team sport. You either have to be very, very good, in which case you become the leader. And then it's easy, cause then you tell people what to do. Or you have to be committed to team work. . There conflict arise.

James is of the view that the role of the team leader is primarily to deliver good performances. According to James, good sports persons are often not the best role models because of the degree of aggression and focus needed to be successful.

The complexity and difficulty relating to the issue of role models are highlighted by James's accounts of how young cyclists acquire negative behaviour, which has been role modeled by some of the older and more experienced cyclists.

The younger guys, they pick up things from the older riders, so there's a lot of respect for the older, more better riders, but they sometimes pick up negative attributes. And they see those as acceptable which isn't the case.

James describes his frustration with team members underper-forming in the presence of a strong team leader. He expresses his discontent with this puzzling and repetitive cycle of behaviour from team members.

'...there's a tendency that when one person can perform, ... the rest of the team will not give their best, because they feel that somebody else will do the job for them.'

James acknowledges the difficulties inherent in dealing with diversity when team members come from different cultural backgrounds. He admits that minority groups could feel isolated, yet contends that it is common for riders to join teams that are from different cultural backgrounds than themselves. It is essential for a professional cyclist to develop the skill to adapt to majority groups.

James stated that the programme has a lenient policy in terms of allowing cyclists ample opportunity to work on aspects underlying their performance prior to considering the termination of their contracts.

So we give them lots of opportunity, but in the end, performance is an important factor. Whether it comes sooner or later, eventually they have to perform.

He was questioned to what extent cyclists are able to continue competitive cycling following their dismissals from the programme when they are required to return their bikes and gear. James explained that cyclists can access bikes and gear through engaging in the programme running a level below the professional programme.

One of the biggest challenges currently faced by the professional team is the limited funding available. The sponsorship to cover the running costs of the programme has not been established and they only have funds available to last until the end of the year. The implications of insufficient funding affect every aspect of the programme.

DISCUSSION

Based on the findings described in the results section of this article, a cross-case analysis was conducted which involved an exploration of all the cases to discern themes common to all cases. A deductive analysis of the environmental factors was done to guide this section, which focusses on how the environment served as a barrier or facilitator to participation in cycling. The discussion is framed by the ICF's subsection of environmental factors, namely products and technology; the natural environment; relationships and attitudes and services, systems and policies18.

Theme I

Surviving on sugar water: Products and technology

The International Classification of Function refers to products and technology as equipment, products and technologies used by people for mobility including those adapted or specially designed18.

Minimal resources are evidently a common theme for the majority of participants in this study. One merely has to attend a cycling race to realise that it is an expensive sport reserved for the participation of those who can afford the bicycles, gear, entry fees and transport to the races. Members of the professional team receive all equipment including their bikes, helmets, tires, gloves, pumps, accessories and supplements from the organisation. In addition, they have access to specialised resources such as a sport psychologist and medical and dietary consultations. The current research argues that the provision of specialised products (such as supplements) and technology (specialised equipment and training) to cyclists from disadvantaged communities is a pre-requisite for equal participation in competitive cycling. Coakley27, a sports sociologist, contends that: "Unless equipment and training are provided, ... young men from low income groups stand little chance of competing against upper income peers, who can buy equipment and training if they want to develop skills"27.

The contracts of two of the participants were terminated due to unsatisfactory performance and they had to return their bikes and gear to the organisation. Although they can still participate in the mass participation programme facilitated by the Cycling Club it seems unlikely that, without the expertise and support of a professional team, the cyclists will be able to successfully make their way back to the arena of professional cycling. It is, therefore, argued that the provision of required nutritional supplements and cycling gear based on performance can therefore not be considered a sustainable facilitator for participation in competitive cycling.

Theme 2

'The place where I come from, some call it the ghettos': The natural environment

The findings agree with those of Fourie, Galvaan and Beeton28who highlighted how something as devastating as poverty, can be experienced in different ways by different people. The effect of township living serves as a barrier to participation and bears a strong relation to poverty. Within the context of the current research it is argued that, when the natural environment can serve as a barrier to participation for one participant (Shaun), it can also serve as a facilitator for others (Leon and Johny). Leon and Johny both described their hardships while growing up and considered these very experiences as the basis to developing self-reliance and contribute towards motivation for sustained participation in cycling. A study by Douglas and Carless29 in the United Kingdom similarly revealed how experienced athletes viewed hardships in a positive light, believing that they helped to develop strength and resilience, which facilitated sport performance. Experiences of the participants related to poverty resonate with the words of John Gilmour30: "Ambitious young sports people emerging from difficult economic circumstances are often driven by this context and they see sport as a possible pathway to economic progress"30.

Theme 3

Appreciating supportive relationships and attitudes

The participants' stories clearly reveal how the presence or absence of support can play a role in facilitating or hindering not only participation but also performance. The sources of support identified are family support, community and team support and having other cyclists as role models.

Within the framework of the ICF, support and relationships refer to persons who provide physical or emotional support in the person's home, family or community life. It does not refer to the attitude of the persons providing support, but focusses on the amount of support provided18. The ICF describes attitudes as "the observable consequences of customs, practices, ideologies, values, norms, factual beliefs and religious beliefs"18. The concept of support is interrelated in terms of relationships and peoples' attitudes.

Family support

Sports sociology literature confirms the positive contribution of support from significant others in enabling successful participation in elite level sport30,31. Occupational therapy literature also suggests that social support leads to motivation facilitating participation in occupation32.

Leon's case reveals how a perceived negative relationship served as a facilitator for participation in cycling as a way to escape from the tension inherent in his relationship with his family.

Our findings show that some participants experienced a lack of family support. Bonisile Ntlemeza33, a life orientation teacher at LEAP school and chairman of the Langa Hockey Club, provides some insight on the role of the parents of Black African athletes: "Most of them tend to come from families where there is one parent, who has to work long hours in order to support the family and as a result, the parent has limited or no time to get actively involved in the child's extramural activities"33.

Sport participation might not be their highest priority as the day-to-day existence of the family has to come first.

The community

From this study, it is apparent that the black cyclists often suffer the consequences of negative attitudes in the form of mocking and disrespect from members in their communities. These reponses could be rooted in jealousy, because cyclists are perceived to have more potential opportunities afforded to them. Although a team sport, cycling is often perceived as an individual sport as it requires cyclists to spend a great deal of time training, mostly on their own. Could cyclists be seen as pursuing their own individual ambitions, and not really contributing to the collective betterment of the community? A possible explanation for this perception could be the way in which sport is linked with access to economic, political and social resources in society27. In this sense, cyclists could be a symbol of inequality while certain opportunities are afforded to some, but not to others.

The team

The findings highlighted the different experiences of participants within the context of their team. Coloured participants, being a minority, seem to experience isolation because of the language barrier and different cultural backgrounds. The importance of team cohesion is confirmed by recent sports literature, asserting that it is an important determinant of motivation amongst athletes34. South African sports literature similarly recommends that coaches give specific attention to the promotion of team spirit in contributing to improved performance outcomes35.

From the coach's feedback, it is evident that conflicting intra-group dynamics affected the cycling team's participation and performance negatively. It is interesting to note that the only participant to relay information on perceived negative team dynamics was Leon, who knew he would never return to the team. Team cohesiveness has been defined as "the dynamic process reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of members' affective needs"34. Cushion and Jones36 also provide useful insights into why young sports participants reserve their opinions. In their study on professional youth soccer, they showed how players perceived coaches as 'gatekeepers' to 'becoming a pro', and players therefore willingly maintained the status quo, deliberately not challenging authority. This aspect was raised in Leon's story. The soccer players in Cushion and Jones'36 study also displayed collective resistance towards coaches by means of engaging in 'output restriction'. The latter implies secretly conserving energy, making an effort not to appear too eager, as eagerness has the potential for a team member to be marginalised by peers36. We suggest that the Cycling Club reconsider the set-up of the team structure. A shift in power is recommended, where the team leader is not necessarily the best rider in the team, but one with leadership abilities and who proves to be a consistent performer. Alternatively, team leaders must be coached to manage their position of power.

'He was my example': The significance of role models

Interaction with role models for upcoming professional cyclists is valued as positively contributing to cycling participation and performance. Participants also regard being a role model to upcoming cyclists as contributing to sustained participation. Supporting this notion, Wicks37 contends that the availability of role models plays a major role in the development of occupational potential although Ngwenya38 confirmed the risks related to the vulnerability of sports stars who serve as role models to so many upcoming youth: "One day they [athletes] are at the top, tomorrow they are not. Then there is the question of social behaviour - will they always behave decently? Very few athletes will at all times stick to proper behaviour - even an icon like Michael Phelps failed the test"38.

Another tension that emerged is that the best performers are not always the most ideal role models, highlighting the significance of not only developing the athletes' skills to perform well, but also their potential to act as role models to upcoming youth39.

Theme 4

'The structure is in place': Services, systems and policies

The structures that govern the Cycling Club and the professional team emerged as an important influence on the performances of cyclists.

Services

According to the ICF's description of environmental factors, services provide structured frameworks designed to meet the needs of individuals18.

The Cycling Club enables opportunities for participation in competitive cycling that are dependent on sponsorships obtained by the managers. It was evident that the current lack of funding for the running costs of the programme is threatening the existence of the programme, which, if not resolved, could limit participation entirely. Services function within systems, governed by policies, which will be explored further.

Systems and policies

Systems consider administrative functions and organisational mechanisms where policies govern and regulate the systems that organise, control and monitor services18.

Systems and policies influence the cyclists' performance and subjective experiences of the programme. Supporting the findings of this study, Flecther and Wagstaff40 contend that "elite athletes do not live in a vacuum; they function within a highly complex social and organisational environment, which exerts major influences on them and their performances" 40. Coakley41 critiques organisations that "are doing little to promote recognition of athletes as human beings rather than performance machines"41. As is often the case in sporting programmes, when participants' performances drop, interventions are aimed at altering individual attributes believed to help them adjust to the requirements of competitive sport41. Instead, this study proposes to rather take account of the role of environment on the performance of athletes and consider altering the environment to facilitate participation and enhance performance. Proposed interventions could include ways of gaining social support from their families and communities to support their participation. Further research into the perspectives of team members and coaches on factors that influence team cohesion could contribute to a better understanding of team dynamics, which could result in improved team performance. It is further contended for the Cycling Club to acknowledge its role and responsibility towards cyclists who are leaving the programme, possibly in the form of an exit strategy. How the Cycling Club will support these cyclists needs to be negotiated and formalised in some form of policy. It is recommended that these negotiations involve all role players including team members.

Limitations

In the absence of explicit examples, the researcher remains uncertain as to how much information participants decided not to share with her based on differences relating to gender, race or class. It has to be stated, however, that these differences could have influenced the findings of the study.

CONCLUSION

The ICF's list of environmental factors highlighted the role of the environment as facilitator or barrier to participation. Environmental aspects include the provision of nutritional supplements and professional cycling gear; the influences of staying in under-resourced communities; appreciating supportive relationships and attitudes and role models and having the relevant structures in place with reference to the cycling organisation. The study differs from conventional sporting interventions such as sport psychology and sport sociology, by focussing on the occupation of cycling and the effect of the environment on sporting performance rather than directly trying to improve sporting performance. Although the cyclists' experiences of environmental factors as facilitators or barriers differed, it is evident that their significance should be considered more carefully by coaching staff. Taking account of the influences of the environment on sporting performance could ultimately improve performances of cyclists who come from disadvantaged communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Cycling Club for allowing us to work with its members and for the practical assistance received along the way. We are indebted to the participants of this study who shared their time, feelings, opinions, dreams and stories.

REFERENCES

1. Liebenberg S. Human Development Report. 2000. <www.com-munitylawcentre.org.za> (13 April 2015). [ Links ]

2. Watson R. New horizons in occupational therapy. In: Watson R, Swartz L, editors. Transformation Through Occupation. London. Whurr Publishers, 2004: 3-18. [ Links ]

3. Watson R, Fourie M. Occupation and occupational therapy. In: Watson R, Swartz L, editors. Transformation Through Occupation. London: Whurr Publishers, 2004: 19-32. [ Links ]

4. Wilcock A. An occupational perspective on health. Thorofare: SLACK Incorporated, 1998. [ Links ]

5. Hammell KW. Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of everyday life. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 71(5): 296-305. [ Links ]

6. United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force. Sport for Development and Peace: Towards Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. 2003. <http://www.un.org/7themes/sport> (1 February 2008). [ Links ]

7. Coalter F. Sport-in-development: A monitoring and evaluation manual. 2005. <http://www.uksport.gov.uk/assets> (1 February 2008). [ Links ]

8. Coalter F. Sport, social inclusion and crime reduction. In: Faulkner GEJ, Taylor AH, editors. Exercise, health and mental health: Emerging relationships. New York: Routledge, 2005. [ Links ]

9. Department of Sport and Recreation South Africa. Sport Development. 2007. <http://www.srsa.gov.za> (15 February 2008). [ Links ]

10. Mashishi M. Towards Equity and Excellence in Sport. 2005-2014: A Decade for Fundamental Transformation and Development. 2005. <http://www.sascoc.co.za> (15 February 2008). [ Links ]

11. Burnett C. Influences on the socialisation of South African elite athletes. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 2005; 27(1): 21-34. [ Links ]

12. Foley P Voices in Youth Development. Marshalltown: Youth Development Network, 2005. [ Links ]

13. Mokwena S. Reflections on the Lost Lessons from the 1970s. In: Foley P, editor. Voices in Youth Development. Marshalltown: Youth Development Network, 2005: 10-26. [ Links ]

14. Elliott DS, Menard S, Rankin B, Elliott A, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D. Good Kids from Bad Neighborhoods: Successful Development in Social Context. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

15. Christiansen C, Baum C, editors. Occupational Therapy: Enabling Function and Well-being. Thorofare: SLACK Incorporated, 1997. [ Links ]

16. Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2002; 56(6): 640-649. [ Links ]

17. Shaw L. Reflections on the importance of place to the participation of women in new occupations. Journal of Occupational Science, 2009; 16(1): 56-60. [ Links ]

18. World Health Organisation. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2001. [ Links ]

19. Wang CC, Yi WK, Tao ZW, Carovano K. Photovoice as a participatory health promotion strategy. Health Promotion International, 1998; 13(1): 75-86. [ Links ]

20. Wang C. Photovoice. 2005. <http://www.photovoice.com.> (26 February 2008). [ Links ]

21. Mitchell C, Moletsane JS, Buthelezi T, De Lange N. Taking Pictures/Taking Action! Visual Methodologies in Working with Young People. 2005. <http://www.ivmproject.ca.> (26 February 2008). [ Links ]

22. Dickerson AE. Securing samples for effective research across research designs. In: Kielhofner G, editor. Research in Occupational Therapy: Methods of Inquiry for Enhancing Practice. Phildelphia: FA Davis Company, 2006: 515-529. [ Links ]

23. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002. [ Links ]

24. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2003. [ Links ]

25. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2007. [ Links ]

26. Citizens Against Racism and Discrimination. South Africa: Racism within the coloured community must be addressed urgently. 2006. <www.card.wordpress.com> (22 January 2014). [ Links ]

27. Coakley J. Sports in Society: Issues and Controversies. 8th ed. Singa pore: McGraw-Hill, 2003. [ Links ]

28. Fourie M, Galvaan R, Beeton H. The impact of poverty: Potential lost. In: Watson R, Swartz L, editors. Transformation through Occupation. London: Whurr Publishers, 2004: 69-84. [ Links ]

29. Douglas K, Carless D. Performance Environment Research. 2006. <http://www.uksport.gov.uk>. (1 February 2008). [ Links ]

30. Heyns F. Healthy minds, healthy bodies. Your Sport, 2008: 1st Quarter: 38-39. [ Links ]

31. Burnett C. The rationale for the multifaceted development of the athlete-student in the African context. Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 2003; 25(2): 15-26. [ Links ]

32. Isaksson G, Lexell J, Skar L. Social support provides motivation and ability to participate in occupation. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 2007; 27(1): 23-30. [ Links ]

33. Heyns F. The good and bad of sport parenting. Your Sport, 2009; 1st Quarter: 28-33. [ Links ]

34. Blanchard CM, Amiot CE, Perreault S, Vallerand RJ, Provencher P Cohesiveness, coach's interpersonal style and psychological needs: The effects on self-determination and athletes' subjective well-being. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 2009; 10(5): 545-551. [ Links ]

35. Andrew M, Grobbelaar HW, Potgieter JC. Sport psychological skill levels and related psychological factors that distinguish between rugby union players of different participation levels. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 2007; 29(1): 1-14. [ Links ]

36. Cushion C, Jones RL. Power, Discourse and Symbolic Violence in Professional Youth Soccer: The Case of Albion Football Club. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2006; 23(2): 142-161. [ Links ]

37. Wicks A. Understanding occupational potential. Journal of Occupational Science, 2005; 12(3): 130-139. [ Links ]

38. Du Toit T. How will the credit crunch affect sponsors? Your Sport, 2009; 2nd Quarter: 26-29. [ Links ]

39. Burnett C. Influences on the socialisation of South African elite athletes. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 2005; 27(1): 21-34. [ Links ]

40. Flecther D, Wagstaff CRD. Organizational psychology in elite sport: Its emergence, application and future. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 2009; 10(4): 427-434. [ Links ]

41. Coakley J. Burnout among adolescent athletes: A personal failure or social problem? Sociology of Sport Journal, 1992; 9: 271-285. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Suzanne Stark

sustark@gmail.com