Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.46 no.1 Pretoria Abr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n1a15

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Family caregivers' perceptions and experiences regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases

Thuli G. MthembuI; Zubair BrownII; Alicia CupidoIII; Gulzari RazackIV; Danielle WassungV

IBSc OT, MPH, PhD candidate - Lecturer, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape

IIBSc OT (UWC) - Occupational Therapy Students at the University of the Western Cape 2014, at the time the study was conducted

IIIBSc OT (UWC) - Occupational Therapy Students at the University of the Western Cape 2014, at the time the study was conducted

IVBSc OT (UWC) - Occupational Therapy Students at the University of the Western Cape 2014, at the time the study was conducted

VBSc OT (UWC)- Occupational Therapy Students at the University of the Western Cape 2014, at the time the study was conducted

ABSTRACT

Family caregivers of older adults with chronic diseases are faced with challenges and health risks regarding their occupational role which influences their health, well-being and quality of life. However, there is limited research about family caregivers regarding their caregiving occupation. This study, thus aimed to explore the perceptions and experiences of family caregivers regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases in the Western Cape, South Africa. A qualitative exploratory-descriptive research design within an interpretive approach was used for the study. Family caregivers aged 21 - 79 years were purposively recruited for the study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with six participants to gain understanding about caregiving and analysed using thematic analysis. Three themes emerged: "God gives his hardest battles to his strongest soldiers", "Keeping ones head above water", and "It's not what it seems". These findings highlighted the importance of occupational balance among family caregivers as they experienced difficulties while caring for older adults with chronic diseases. Therefore, this study contributes to the knowledge for occupational therapists who provide interventions to older adults and family to consider their health needs. Thus, occupational therapists may need to develop programmes that focus on family caregivers' strategies to enhance their occupational balance.

Keywords: family caregivers, perceptions, experiences, caring, older adults, chronic diseases

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with chronic diseases are entitled to non-discrimination; to be treated with dignity, to be respected and to be protected from harm, abuse and violence1. According to Malherbe1, families in various communities are expected to carry some of the responsibilities of providing social support and caregiving to the older adult. These families also play a significant and critical role in the older adult's welfare although this role may have a negative influence on the psychological and physiological health of the caregiver. A family caregiver is defined as anyone who provides unpaid physical and emotional care to an ill or disabled loved one at home including parents, children, spouses, as well as neighbours and friends2,3. Tang and Chen4 show that there has been an increase in health risks among family caregivers which influences their well-being and quality of life. These health risks have been identified as influencing the family caregivers' role and include social isolation, lack of knowledge, limited skills, personal coping styles, stress, depression, anxiety, poor sleeping habits and physical health complications2,4,5,6,7,8,9. Caring for older adults with chronic diseases can also result in occupational imbalance as a result of family, career, and care giving demands5.

Systematic reviews have been carried out to appraise previous studies related to the family caregivers' experiences, needs, and support as well as the effects of caring for an older person with chronic diseases2,8,9,10,11. These systematic reviews indicated that most studies on family caregivers were conducted in the USA, Canada, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. However, there is limited knowledge regarding the experiences of family caregiv-ers who provide care to older adults with chronic diseases on the African continent12. Therefore, it is apparent that more research is needed for occupational therapists to have an understanding of the challenges and occupational imbalances faced by family caregivers of older adults with chronic diseases. Consequently, previous studies by Oyebode13 and O'Sullivan14 have suggested that occupational therapists should be aware of family caregivers' needs related to a healthy lifestyle in order to provide support and foster coping skills.

To our knowledge, there is limited research conducted on the perceptions and experiences of family caregivers regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases in the Western Cape, South Africa. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the perceptions and experiences of family caregivers regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases. Additionally, the objectives of the study were to explore the facilitators and the barriers that influence the occupational balance of family caregivers that care for older adults with chronic diseases. It was foreseen that the study could contribute to our knowledge about improving the occupational balance of family caregivers who may experience health risks and caregiver burdens by designing intervention programmes which would be evidence-based.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Challenges experienced by family caregivers can be understood when considering their occupational imbalance. According to Townsend and Wilcock5, occupational imbalance is experienced by people who are un-occupied, under-occupied or over-occupied. Regarding the literature that deals with the challenges faced by family caregivers, it could be argued that they experience challenges in balancing their occupational demands related to their caregiver role, family, and career15. Previous studies reported that family caregivers seemed to experience caregiver burden, as they spent most of their time providing (or helping with) the self-care activities of the older adults5,16. A qualitative study by Ae-Ngibese et al.17 conducted in Ghana explored the experiences of caregivers of people living with serious mental disorders. The results indicated that the caregivers prepared meals and fed their loved ones, as well as assisting their relatives during nature's call. Similarly, the results of the study reported a variety of challenges related to the stress and burden experienced by caregivers such as financial difficulties, social isolation, emotional stress and depression. However, most of the studies reviewed did not report on how caregivers balanced their personal and family members' needs.

Additionally, several studies found that family caregivers struggled to cope with the chronic stress and emotional disturbance related to caring for an older person with a chronic disease9,11. Most of the systematic reviews reported that family caregivers had 'no life anymore' and that they lacked freedom to exercise their occupational rights to work, explore interests as well as engage in social participation with friends, relatives and partners2,8,9,10,11,12. Previous studies looked at the effect of providing care for family caregivers in terms of their physical health, psychological well-being, social life, financial situation and quality of life which appeared to form part of their burden3,8,910. These studies found that the family caregivers' social life such as going on holiday, engaging in social activities, maintaining telephone contacts, visiting friends and attending recreational and social clubs were negatively influenced by providing care to older adults with chronic diseases7.

METHODS

Study design

A qualitative exploratory-descriptive research design with an interpretive worldview was used to explore the perceptions and experiences of family caregivers caring for older adults with chronic diseases18,19,20. An interpretive worldview will contribute to our understanding of the human behavior and social phenomena of caring for older adults with chronic diseases18.

Participants

The population comprised family members living with an older adult with chronic diseases who were known to the researchers ZB, GR, DW and AC and who resided in the Southern and Northern suburbs as well as Cape Flats in Cape Town. Purposeful sampling21,22 was used to recruit six of these caregivers who were assisting their family member in a variety of tasks such as bathing, dressing, taking medication and using an oxygen breathing apparatus; and who were unpaid for their services. Furthermore they had to be willing to provide rich and relevant information about providing this care.

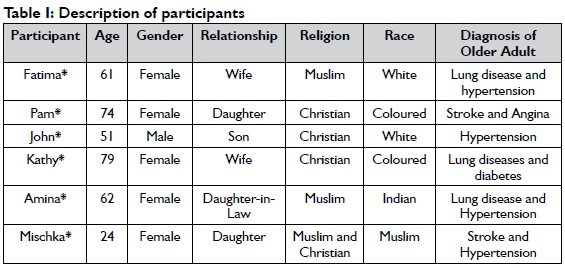

The participants that consented to be part of this study were predominantly females (n = 5; 83.3%) and one male (n=l; 16.6%). All of them were caring for an older adult over the age of 60 and were residing within the same household as the older adult. The participants' ages ranged between 24 and 79 years. Three of the participants were coloured, two were white and one was an indian. Three of the participants belonged to the Christian religion, two were Muslim, and one stated that she combined the two religions. (See Table I)

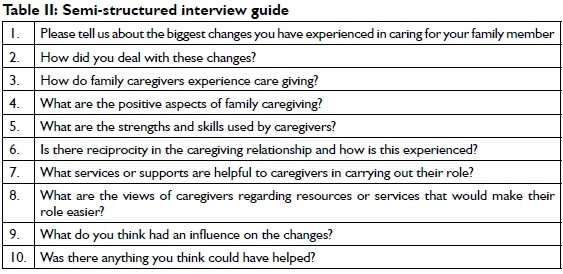

Data collection Semi-structured interviews

The data collection was conducted through face-to-face, semi-structured interviews23 with the participants within their households in order to gain an understanding and insight into their perceptions and experiences of caring for an older adult with chronic diseases. The researchers used an interview guide (Table II) to understand and gather the views of the participants. Authors contributions towards data collection: ZB (conducted one interview with Amina), AC (conducted two separate interviews with Kathy and Mischka), GR (conducted one interview with Fatima); and DW (conducted two interviews with John and Pam). These semi-structured interviews lasted for about 40 to 60 minutes and were conducted with each participant at each household. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. TGM supervised and critically reviewed the whole process, provided input regarding occupational therapy perspective, and prepared the manuscript.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used for the purpose of interpreting and analysing the data24,25. All the researchers read through the transcripts several times in order to familiarise themselves with the data as well as to notice and search for patterns of meaning and issues of interest in the data. Subsequently, codes were developed through discussion and a colour for each code was created, while comments were also made on the margins of the transcripts. The researchers identified and grouped all codes with similar meanings together in order to create categories. In addition, themes were defined and named based on the relationship between categories. Some of the themes were named through the use of in vivo that provided direct verbatim text from the participants' responses. Lastly, the researchers wrote a narrative report supported by excerpts from the participants' responses as evidence of the data.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was enhanced through strategies of credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability26,27,28. Credibility was ensured through prolonged engagement with the family caregivers during the semi-structured interviews which lasted for 40 - 60 minutes per session. Member checking was conducted in order to ensure that the data collected was a true reflection of the participants' perceptions. Peer debriefing was done with the first author as a supervisor and peers within the department of occupational therapy in order to reflect and debate on the whole research. Confirmability was ensured through the provision of an audit trail and description of the steps of data analyses that makes it possible for the research process of the study to be tracked. Dependability was enhanced through the use of reflexive journals to ensure that no information was omitted during the interviews and that the researchers and supervisor reach consensus in relation to the findings. Transferability was ensured through the use of the purposeful sampling method to recruit family caregivers who were providing care for the older adults with chronic diseases according to specific inclusion criteria.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Senate Research Committee of the University of the Western Cape (ethics clearance registration no 12/8/14). The recruitment of the participants was conducted after ethics' approval was obtained. The participants were given information about the purpose of the study and they consented to participate in the study. In addition, the participants were informed that participation in the study would be voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any repercussions. Pseudonyms were used for reporting the findings in order to protect the participants' privacy and confidentiality.

RESULTS

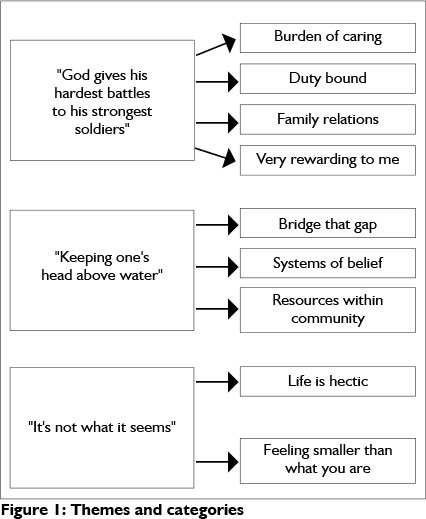

Three themes emerged from data analysis: (1) "God gives his hardest battles to his strongest soldiers"; (2) "Keeping ones head above water"; (3) "It's not what it seems". Figure I illustrates the themes and categories.

Theme 1: "God gives his hardest battles to his strongest soldiers"

Burden of caring

With regards to the burden of caring, family caregivers expressed that caring for an older adult with a chronic disease was a demanding occupation which appeared to influence them mentally, physically and emotionally. The family caregivers further reported that providing care for older adults was a burden for them as they had to grapple with various occupations including work and cooking. Furthermore, some of the family caregivers perceived caregiving as a frustrating task which caused them to cry, and to sometimes use liquor.

"It is very taxing, and I have been looking after them for some time now, especially when you come home and you tired, you can't sit, you got to cook food for the next day and all that. I am mentally, physically and emotionally tired." Amina

"There were times that I got a bit frustrated and I would go sit on the steps outside, and I would pour myself rum and I would sit and cry a bit....Now and then, a little alcohol helped me. No, alcohol did not make me forget about my challenges. Alcohol just relaxes me, actually all your muscles. If things get too much I would take a drink." Mischka

Time constraints were consistently perceived by the family caregivers as a barrier to caring for an older adult. Some of the family caregivers decided to give up their jobs in order to provide care for the older adult. In addition, the family caregivers reported that they were struggling to balance their daily occupations, work, and educational activities as well as providing care for an older person. They further indicated that they had no time to rest as the demands of caring for the older person were "above their shoulders". Some of the family caregivers reported that they did not have a social life, as they had to accommodate the older adults' needs including basic activities of daily living around the clock, in addition to their own work load.

"When she is not well, I've got to sort of rally around work and seeing to her, and it can becomes a bit awkward....I also do private work on the side that also takes a lot of my time, less time to be at home, should something go wrong. " John

"I need to study my books at night but I am too tired, and feel that I just need to finish and go to sleep. In the middle of the night I might also get up once or twice..." Amina

Two of the six family caregivers, Pam and Kathy reported that they were struggling with finances in order to pay for accommodation, medication and toiletries.

"It's the grandchildren and myself and my brother, everybody gives the same amount every month to pay for an accommodation, carer and diapers. It's quite a lot to remember, ... to buy everything including diapers, wet wipes, tablets, soap and powder and all that, the pension doesn't cover everything." Pam

"We have medical-aid to cover most of the things. We have had the machine now for 4 years, and the vital oxygen. The medical-aid pays RI000, 00 per month." Kathy

Duty bound

In relation to being duty bound, the family caregivers felt that caring for older adults was something they did not choose, and they had no option but to acknowledge the demands of this role. They further stated that they were bound to care for the older adult due to circumstances. In addition, the family caregivers said that they had to leave their jobs and social life in order to optimally take care of the older adult. In one example relevant to this, Kathy mentioned that their religious obligations and promises made to God were part of the reasons why she provided care for her husband as she was duty bound.

"Since my dad passed away 2 years, he is not here anymore. I mean she is going to be 83, she is not always well. You have to sacrifice your time to, accommodate her. You have to give up certain things. When she is fine you've just got to be here at home, from time to time, just to ensure on the off chances that she might get sick you know." John

"I'm duty bound like a Christian would be. When we got married we said for richer and for poorer, in health and illnesses. I'm married, that's why I'm doing the things that I am doing. I'm duty bound." Kathy

Family relations

While reflecting on their experiences, Amina and Mischka reported that they did not receive any support and assistance from other family members. They further indicated that some of the family members were unwilling to share the role of caring for their parents. For example, Amina as a daughter in-law caring for her father in-law shared that the biological siblings of her father in-law were not assisting in caring for their brother which resulted in family dynamics.

"If they want to come and be by him for a while, then they must come and be with him till I come home or so, but I do not see why I must call them to come and sit a little bit by their brother, or to come and help, they should know out of their own, after all, he is their brother. " Amina

"My mother felt that my father brought this onto himself, because he was not looking after himself and she blamed him, because she is a nurse herself, and they were always fighting with each other at that stage. She decided to file for divorce, and she decided now, she wants to sell everything and go on with her life." Mischka

Very rewarding to me

Two of the six family caregivers, Fatima and Amina reported that caring for older adults was very rewarding as they were able to have connections, attachment and support as family members. Some of the attributes which were identified and related to caring for older adults with chronic diseases included insight, patience, compassion, dedication and emotional strength.

"It depends on the support system, if you got a good support system then it is fine, the people that supports you will be there through the process of taking care of the loved one while they cannot do it for themselves, and then you must just make use of that support system, because it can become too much to handle by yourself. The family, we bonded through this situation, yes the whole family, and now that I have cancer, I can see the support from the family showing again." Fatima

" It is very rewarding, I would say in life, to become a care giver, how can I say, it's not for the light hearted. It takes lots of time, dedication, compassion, and patience. You also need to remember that although the older adult may look big, they actually go back to being like a baby, so you as a caregiver shouldn't be afraid, if something goes wrong, as just like a new mother, every day you learn new things." Amina

Theme 2: "Keeping one's head above water" Bridge that gap

In contemplating bridging that gap, Mischka, Fatima and Amina reported that relatives' support enabled them to relieve their stress and cope well with the challenges of caring for the older adult. They also confirmed that they attended support groups to increase their motivation in order to carry on with caregiving.

"I had a nephew that helped me look after him. He did the maintenance in the house and was able to drive. As I did not have a driver's license at that time, so he kind of helped me." Mischka

" We knew what was going to happen, but we had to buckle up and be there. The strength I got from everybody that's what supported me, all the children came on the off nights, there was lots of support, even when they could not come, they used to phone and check if everything is going fine and ask if they could do anything." Fatima

" I think that all those things gave me, strength, and other people were also looking at me, and the people always tell me, that you will get through it, because you are strong. I actually feel that this conversation helped me to off load a bit, as you would call it. " Amina

Systems of belief

Two of the family caregivers, Amina, and John highlighted that their belief system enabled them to cope with caring for older adults. They further expressed that their religion was a source of support that facilitated the transformation of their mind-sets. The family caregivers also shared that prayer was one of the spiritual occupations that they perceived as an enabler to relieving the stress of caring.

"Always remain positive in everything that you do, but when you do things that are positive and your beliefs are strong, you will achieve whatever you want to achieve. With prayer, I think there are things that I pray for, that you feel much lighter... I really appreciated that because it was knowledge that I wouldn't get from anybody else. " Amina

"From a Christian point of view, Christianity teaches you to respect your elders. I mean they raised you. In my case, I mean, my mother raised us to the best of her ability. " John

Resources within the community

With regards to resources within the community, Fatima, Mischka and Amina reported that they were supported by social workers and an occupational therapist from the community and hospice. They further indicated that the support they received from these healthcare professionals assisted them in managing their burdens and challenges. For example, according to the three family caregivers, they were able to make adaptations in their home environment in order to meet the older adults' needs.

"I had hospice behind me, because hospice came to help, and do home visits to talk to me, asked how I was doing, and if I needed anything. There were a few things that she brought with that I could use, nursing my husband." Fatima

"An occupational therapist said, I should put posters on the wall, give him adaptive devices and they just gave me a lot of information, to lighten up the circumstances at home. Yes, it mentally prepared me for this role. It makes life much easier, because now you know how to dress the person, what type of cutlery to use, how to bath, etc. It just helps you a lot... The social workers are the best. They assisted me by referring me for guidance. If she did not refer me, I think I would have paid RI500 for the course, but I did not pay a cent." Mischka

With reference to support from the employers, Mischka shared that the employer accommodated and supported her during the difficult times, and her work schedules were adjusted in order to allow her to care for her father.

"I told him about everything, when my father got sick and things were not going well at home, and I was looking after my father. He would understand, and always make a plan for me. He was very supportive with me. It is a good thing that your employer also knows what is going on at home." Mischka

Theme 3: "It's not what it seems" Life is so hectic

Three of the six family caregivers, Fatima, John, and Mischka shared that caring for an older adult with chronic disease had a negative influence on their personal, social and work life as they lacked balance. Therefore, the family caregivers were highly stressed and they were constantly worried about the older adult.

"I gave up my job for the month, without leave, I was still working at the time." Fatima

"I needed to be at work, and I needed to know what is happening at home, as well, because she does not have anybody to look after her." John

"I decided to go study medical secretarial at college in order to seek for a well-paid job. At that stage, I also worked at restaurants at night to support my study fees and help with buying food in the house etc." Mischka

Feeling smaller than what you are

Two of the six family caregivers, Mischka and Amina expressed that caring for an older adult was related to a role reversal, as they were expected to care for their parents and to take on the whole responsibility. In addition, the only male participant reported feelings of being alone in the world of caring for his mother which made him experience a sense of isolation and alienation from social life.

"It was physically draining, and he was wearing nappies, so when I had to clean him, I had to clean him with a cloth. I tried to potty train him, you see if someone had a stroke you have to teach that person from the start how to eat again, how to go to the toilet and it was not always that easy." Mischka

"He messes his pants, not quite sure if his stomach wants to work. Then I need to read my books that time of the night, I am too tired, and feel that I just need to finish and go and sleep." Amina

"Sacrifices, I'm not a married guy, I'm a single guy in that sense, I can just come and go, as I please, and do as I please. When I want to go or do what I want to, but I have to consider my mothers' rights, I need to be there to help her. I have to sacrifice my own time and accommodate her; I got to give up certain things even when she is fine. " John

DISCUSSION

This study explored family caregivers' perceptions and experiences regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases. Generally, the findings of the study highlighted the importance of improving occupational balance of the family caregivers who experience health risks and caregivers' burden. The findings of the study revealed that family caregivers lived a hectic life as they noticed that providing care to an older adult was a difficult occupation and that they were struggling to balance their caregiver role with work and social life. Hence, the findings corroborate with Townsend and Wilcock's5 explanation that over-employed people seem to be at risk for ill health as they are always busy looking after themselves, their families or their communities. This could mean that occupational therapists may need to consider the needs of family caregivers when planning interventions to address the caregiver burden and promote their health and well-being as part of client-centred practice.

This study highlights the value of religion, religious obligations and vows made in relation to the occupational role of being a family caregiver. Accordingly, the family caregivers' religion was perceived as an enabler for enhancing their quality of life and ability to cope with the demands of their caregiver role. The current findings concur with those of previous studies which reported that prayer seemed to be a facilitator for communication with God to assist the growth of good attributes such as patience, compassion, strength and love as well as to sustain their internal healing and acceptance of their challenges29,30,3I,32. This was perhaps related to the fact that the caregivers were grounded in Christian and Muslim religions which assisted them to have resilience, to persevere and to find meaning within their responsibilities.

It should be noted that previous research has indicated that caregivers received less assistance from health professionals in balancing their tasks and emotional demands of caregiving33. However, the results of this study in the theme "keeping one's head above water"; indicated that the participants were receiving support from health professionals including occupational therapists and social workers. This could possibly be explained by the fact that the family caregivers recognised the value of an effective referral system, as well as the value of the services that they received from the other stakeholders they were referred to. Another possible explanation might be that some of their financial burdens were decreased, as the family caregivers did not pay for the services that they received. Additionally, the family caregivers indicated that the occupational therapists provided them with helpful information on how to adapt the home environment in order to accommodate the older adults' needs. This is consistent with previous studies which suggested that healthcare professionals should provide family caregivers with information relevant to their needs in order to support them34,35.

The present study only focused on the family caregivers' needs, without any involvement of other stakeholders in particular those who deal with compensation for social security, health insurance and local resources. Therefore, this suggests other avenues which may be considered in order to provide support to family caregivers and older adults. However, Samaad36 like Turcotte et al.37 echoed by the Department of Social Development38 suggest that partnerships be developed in order to help the process of integrating home-based services within government departments such as health, education, housing and local government as well as Non-Governmental Organisations like faith based organisations. This could assist in strengthening the relationships among all stakeholders that provide care and support for older adults and family caregivers. In addition, efforts to prioritise policy making as well as advocacy for the establishment of older person's forums in order to lobby for older persons' needs36 could be strengthened. Therefore, Ramugondo and Kronenberg39 emphasise the importance of collective occupations whereby humans work together to enhance their relationship and capabilities in caring occupations. This is consistent with Asuquo et al.'s40 view that providing information and training to family caregivers could assist them in their caring role. Additionally, this finding corroborates previously reported findings that highlighted the importance of involving government and non-governmental officials in improving the role of support groups in promoting the health, well-being and quality of life of older people and family caregivers^.

Strengths and limitations of the study

As this was a qualitative study, caution must be applied as the findings apply to the participants of the present study and might not be transferable to other family caregivers. In particular, this study provided an understanding of the perceptions of family caregivers regarding caring for an older adult with chronic diseases. The contribution of this study is obvious as the findings can be capitalised as evidence to build public policies for promoting the health, quality of life and well-being of family caregivers and older adults.

Implications for clinical practice, education and research

The study was conducted with family caregivers in urban areas. There is a need for a similar study to be conducted with family caregivers of older adults with chronic diseases in rural areas. The findings of the study may be used as a foundation to develop intervention programmes for meeting the needs of family caregivers. Additionally, the findings may be used in occupational therapy education on the role of the occupational therapist in chronic diseases.

CONCLUSION

This study explored family caregivers' perceptions and experiences regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases. The findings of the study highlighted the significance of improving the occupational balance of family caregivers. The study makes several noteworthy contributions in generating an understanding of the coping strategies utilised by family caregivers and the barriers that they perceived to have a negative effect on the care provided to older adults with chronic diseases. This research could serve as a basis for creating supportive partnerships between occupational therapists, family caregivers and other stakeholders in the community in order to advocate for services to address caregivers' needs. The findings of the study assisted in gaining an understanding of the barriers to occupational balance experienced by family caregivers that care for older adults with chronic diseases. Similarly, the study provided insight into the facilitators of occupational balance of family caregivers providing care to older adults with chronic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the participants for consenting to participate in the study and share their perceptions and experiences.

Additionally, we thank the University of the Western Cape and Occupational Therapy Department for granting the approval to conduct the study.

REFERENCES

1. Malherbe, K. Older person Act: Out with the old and in the with the older? Law Democracy and Development, 2007, 53-68 [ Links ]

2. Stoltz, P, Udén, G., and Willman, A. Support of family carers who care for older person at home-a systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 2004; 18(2): 111-119 [ Links ]

3. Mphuthi, D.D. Coping behaviours of haemodialysed patients' families in a private clinic in Gauteng. Unpublished Masters Thesis; North West University: Potchefstroom. 2010. [ Links ]

4. Tang, YY, and Chen, S.P Health promotion behaviors in Chinese family caregivers of patients with stroke. Health Promotion International, 2002; 17(4): 329-339 [ Links ]

5. Townsend, E. and Wilcock, A. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: A dialogue in progress. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 71(2): 75-85. [ Links ]

6. Fee, H.R., and Wu, H.S. Negative and Positive Care giving Experiences: A closer look at the intersection of gender and relationships. Centre for family and demographic research, 2011; 07: 1-32. [ Links ]

7. Raschick, M. and Ingersoll-Dayton, B. (2004). The costs and rewards of care giving among aging spouses and adult children. Family relations, 53(3): 317-325. [ Links ]

8. Greenwood, N., Mackenzie, A., Cloud, G.C. and Wilson, N. Informal primary carers of stroke survivors living at home-challenges, satisfaction and coping: a systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2009; 31(5): 337-351. [ Links ]

9. Mckeown, L.P, Porter-Armstrong, A.P and Baxter, G.D. The needs and experiences of individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 2003; 17(3):234-248. [ Links ]

10. Greenwood, N., Mackenzie, A., Cloud, G.C. and Wilson, N. Informal carers of stroke survivors - factors influencing carers: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2008; 30(18):1329-1349. [ Links ]

11. Greenwood, N. and Smith, R. Barriers and facilitators for male carers in accessing formal and informal support: A systematic review. Maturitas, 2015; 82:162-169 [ Links ]

12. Greenwood, N., MacKenzie, A., Harris, R., Fenton, W. and Cloud, G. Perceptions of the role of general practice and practical support measures for carers of stroke survivors: a qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 2011; 12: 57. [ Links ]

13. Oyebode, J. Assessment of carers' psychological needs. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 2003; 9: 45-53. [ Links ]

14. O' Sullivan, A. AOTA's Statement on Family Caregivers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2007; 61(6): 710. [ Links ]

15. Gómez-Olivé, X. The health and well-being of older people in rural South Africa. Available Online: http://www.phasa.org.za/the-health-and-well-being-of-older-people-in-rural-south-africa/. Time: 12:36.2012. [ Links ]

16. Yerxa, E.J. Occupational Science: A renaissance of secure of humankind through knowledge. Occupational Therapy International, 2000; 7(2), 87-98 [ Links ]

17. Ae-Ngibese, K.A., Doku, VC.K., Asante, K.P. and Owusu-Agyei, S. The experience of caregivers of people living with serious mental disorders: a study from rural Ghana. Global Health Action,2015, 8: 26957 - http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26957. [ Links ]

18. De Villiers, R. Three approaches as pillars for interpretive information systems research: development research, action research and grounded theory. Proceedings of SAICSIT. 111-120. [ Links ]

19. Rotchford, A.P, Rotchford, K.M., Mthethwa, L.P and Johnson, G.J. Reasons for poor cataract surgery uptake. A qualitative study in rural South Africa. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 2002; 7(3): 288-292. [ Links ]

20. Burns, N., and Grove, S. K. The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. 2009. [ Links ]

21. Dolores, C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection, Department of Botany, University of HawaPi. Research and Applications, 2007; 5: 147-158. [ Links ]

22. Tong, A., Sainsbury, P and Craig, J. Consolidating criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality of Health Care. 2007; 19(6):349-357. [ Links ]

23. Harrell, M. C. and Bradley, M. A. Data collection methods: Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2009. [ Links ]

24. Patton, M.Q. and Cochran, M. A guide to qualitative research: Health Services Research Unit, London: School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2002. [ Links ]

25. Braun, V and Clarke, V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006; 3(2): 77-101. [ Links ]

26. Graneheim, U. H. and Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 2004; 24: 105-112. [ Links ]

27. Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1991; 45(3): 214-222. [ Links ]

28. Kennedy, M. and Julie, H. Nurses' experiences and understanding of workplace violence in a trauma and emergency department in South Africa. Health SA. Gesondheid, 2013; 18(1), Art. #663, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18il.663. [ Links ]

29. Koerner, S.S., Shirai, Y and Pedroza, R. Role of religious/spiritual beliefs and practises among Latino family caregivers of Mexican descent. Journal of Latino/Psychology, 2013; 1(2): 95 - 111. [ Links ]

30. Broodryk, M. and Pretorius, C. Initial experiences of family caregivers of survivors of a traumatic brain injury. African Journal of Disability, 2015; 4(1): Art. #165, 7 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v4i1.165. [ Links ]

31. Mthembu, T.G., Ahmed, FF, Nkuna, T. and Yaca, K. Occupational Therapy Students' Perceptions of Spirituality in their training. Journal of Religion & Health, 2015; 54(6): 2178-2197. DOI: 10.1007/s10943-014-9955-7. [ Links ]

32. Mthembu, T.G., Abdurahman, I., Ferus, L., Langenhoven, A., Sablay, S. and Sonday, R. Older adults' perceptions and experiences regarding leisure participation. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 2015; 21(1:1): 215-235. [ Links ]

33. Reinhard, S.C., Given, B., Petlick, N.H. and Bemis, A. Chapter 14 Supporting family caregivers in providing care. Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses, 1; 341-404. [ Links ]

34. Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B.P and Glass, R. Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 1999; 89: 1187-1193. [ Links ]

35. Stewart, M., Barnfather, A., Neufeld, A., Warren, S., Letourneau, N. and Liu, L. Accessible support for family caregivers of seniors with chronic conditions: from isolation to inclusion. Canadian Journal of Aging, 2006; 25(2): 179-192. [ Links ]

36. Samaad, A. Population ageing and its implications for older persons: An analysis of the perspectives of government and non-government officials with the Department of Social Development sector. Unpublished Masters Thesis. University of South Africa: Pretoria. 2013 [ Links ]

37. Turcotte, P., Carrier, A., Desrosiers, J. and Lavasseur, M. Are health promotion and prevention interventions integrated into occupational therapy practice with older adults with having disabilities? Insights from six community health settings in Québec, Canada. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2015; 62: 56 - 67. [ Links ]

38. Department of Social Development. Older Persons Act, South African Government Gazette, 2006. [ Links ]

39. Ramugondo, E.L. and Kronenberg, F. Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: Bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science, 2013; (in press). [ Links ]

40. Asuquo, E.F., Etowa, J.B. and Adejumo, P Assessing the relationship between caregivers' burden and availability of support for family caregivers' of HIV/AIDS patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria. World Journal of AIDS, 2013; 3: 335 - 344. [ Links ]

41. Noohi, E., Peyrovi, H., Goghary, Z.I. and Kazemi, M. Perception of support among family caregivers of vegetative patients: A qualitative study. Consciousness and Cognition, 2016; 41: 150 - 158. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Thuli Mthembu

tmthembu@uwc.ac.za