Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.46 no.1 Pretoria Abr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n1a11

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Meaning and purpose in the occupations of gang-involved young men in Cape Town

Lisa WegnerI; Ayesha BehardienII; Cleo LoubserIII; Widaad RykliefIV; Desiree SmithV

IBSc OT (Wits), MSc OT (UCT), PhD (UCT) - Associate Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape

IIBSc OT (UWC) - Students in the Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape at the time the research was conducted

IIIBSc OT (UwC)- Students in the Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape at the time the research was conducted

IVBSc OT (UWC) - Students in the Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape at the time the research was conducted

VBSc OT (UWC) - Students in the Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape at the time the research was conducted

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Involvement in gangs negatively influences the lives of many young men living in Cape Town, South Africa. There is a need to better understand young men's motives and reasons for belonging to gangs as efforts to reduce gang involvement have shown little success.

METHODOLOGY: A descriptive qualitative study was conducted to explore the meaning and purpose of engaging in occupations related to being a gang member, and the influence on other occupations. In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with four participants who were purposively selected from a Special Youth Care Centre in Cape Town.

FINDINGS: Five themes emerged: Why am I where I am?; To strengthen the camp; Attraction to gangs; It's difficult but it's life; and Threshold to manhood. The participants' involvement in gangs meant social support, material resources including drugs and money, independence, thrills and excitement. The purpose of engaging in gang-related occupations was to strengthen the gang, gain belonging, prove manhood and for survival. However, gang-involvement deprived participants from engaging in other occupations and roles including schooling, leisure activities and relationships with mothers and girlfriends.

CONCLUSIONS: Understanding gang-related occupations assists occupational therapists to plan relevant programmes to support young men's disengagement from gangs and reintegration into the community in pro-social ways.

Keywords: gang-involved young men, occupations, meaning, purpose

INTRODUCTION

Gang involvement negatively influences the lives of many young men living in Cape Town, South Africa. There are approximately 130 gangs operating in Cape Town with membership estimated at around l00 000 individualsl. Gangs have been portrayed as an anti-social way of life demanding loyalty from members before loyalty to institutions of civil society such as family, school, the justice system and religion2. The risk factors, as well as the delinquent and criminal activities associated with gang involvement have been well documented3,4. In 20ll, former mayor of Cape Town Helen Zille noted in her State of the Province Address5 that risk activities linked to gangs, including crime, substance use and high school dropout, had increased. Interventions aimed at preventing or reducing gang involvement have shown little success, which indicates the need to better understand the motives and reasons why young men become involved in gangs. Occupational therapists believe that occupation gives meaning to life, and are therefore well placed to explore the meaning and purpose of young men's involvement in gangs. However, there is little previous research in this area by occupational therapists.

Gangs and gang violence are not new to the political landscape of South Africa; since the 1920's there have been documented records of gang activities6. However, in recent years, street gangs have been linked to larger and more sophisticated criminal networks. Of concern is that the gangs actively recruit young boys and adolescents into their ranks. There are many reasons for children getting involved in gangs including poverty, problems at schools, dysfunctional societal structures, family problems and drug addiction7. Environmental constraints and a lack of pro-social opportunities and resources such as sports, cultural activities and recreational facilities, leave young people with few choices other than getting involved in gangs or staying at home7. In a qualitative study conducted in Cape Town, adolescent participants perceived boredom in their free time to be associated with involvement in risky activities including using drugs and violence8.

The phenomenon of gang involvement has previously been investigated from a sociological and a psychological perspective. The current study provides an alternative perspective by using an occupational approach to provide insight into the occupational needs that are met through young men's engagement in gangs and gang-related occupations. Occupations are the roles, routines and activities of everyday life that shape identity and structure time9. Meaning refers to "the sense that a person makes of a situation" through the interpretation of perceptual, symbolic and affective experiences10:776. Purpose is the desire for an expected outcome through the performance of a meaningful occupation10.

There is little previous research by occupational therapists about gang-involved youth. Whitefordll conceptualised gang participation as a product of sustained occupational deprivation, in other words, not being able to engage in meaningful activities due to factors beyond one's control. Kronenberg12 described an occupational therapy pilot project in Guatemala called 'Survivors of the street' with street children, many of whom were part of youth gangs, and as such were marginalised by Guatemalan society. The project adopted a 'rights-based approach' to 'offer the children opportunities to connect with their interests and enable them to identify and build on their strengths'l2:269. A study of children involved in gangs in Los Angeles, USA, found that although their occupations provided them with some sense of meaning, this did not result in the advantages they believed the gangs promised but rather ended in a downward spiral of substance abuse, violence, incarceration and, frequently, death at a young age13. No similar studies conducted by occupational therapists in South Africa could be found in the review of literature.

Therefore, the following research questions were addressed in the present study: what is the meaning and purpose of engaging in occupations related to being a gang member? How are other occupations influenced by engagement in gang occupations?

METHODOLOGY

In this study, a descriptive qualitative research design was used to explore and describe the experiences of four young men who were involved in gangs in Cape Town. Sandelowski14339 argues that descriptive qualitative research is 'a valuable and distinctive component of qualitative health sciences research' providing a comprehensive summary of events and the meaning that participants attribute to these events. Specifically, the objectives of the study were to explore and describe the perceived meaning and purpose that young men associated with the occupations related to being a gang member, and their perceptions of how other occupations were influenced by their gang involvement.

The study took place in 2011 at a Special Youth Care Centre in Cape Town that catered for 200 young men aged 13 to 17 years who were charged with committing crimes and in need of restrictive placement whilst awaiting trial. The study received ethics approval from the Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of the Western Cape. The Director of the Centre gave permission for the study to be conducted, and consented on behalf of parents for the participants to take part as they were under the care of the Centre. Purposive sampling was used to select four participants (three were 17 years old and one was 16 years old), who were male, identified themselves as belonging to a gang, and who lived in Cape Town. The occupational therapist at the Centre selected a group of ten young men who met these inclusion criteria and who she deemed to be 'information-rich'l4:338. The ten young men were invited to take part in two creative arts activity group sessions facilitated by the researchers. The goal was to develop interpersonal relationships with the young men and identify potential participants who could best articulate their experiences. Four young men were invited, and all agreed through informed consent in writing, to take part in the study. Participants chose pseudonyms for themselves in order to protect their identities.

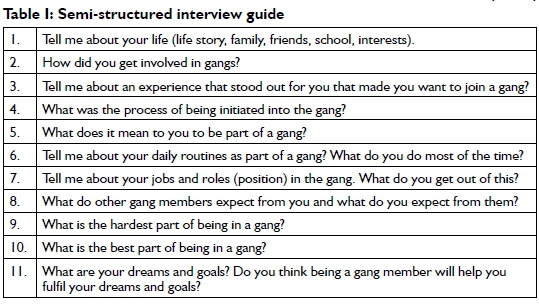

In-depth, semi-structured interviews (lasting 60 to 90 minutes) were conducted with the four participants, and took place in a quiet room at the Centre. Each of the four researchers interviewed a different participant using the same semi-structured interview guide (Table I) to ensure consistency and conformity between interviews. Interviews revolved around core questions with spontaneous prompting to facilitate elaboration on specific topics and were audio-taped.

Qualitative content analysis15 was used to analyse the data. This process involved the verbatim transcription of the interviews by the researchers to ensure close proximity to the data. The transcripts were read by all of the researchers to get an in-depth sense of the data in relation to the research questions, aim and objectives. Each researcher individually identified meaning units (phrases or sentences) which were named as codes. The codes were then grouped into categories according to patterns and similarities in meaning. The researchers discussed and revised these categories to obtain a final list of categories. The categories were described and then grouped into five themes based on similarities. Once the team was satisfied that the themes reasonably represented the data gathered, the themes were used as a basis for the construction of the academic argumentl5.

Rigour and trustworthiness of the research process were ensured in several ways. Credibility and dependability (meaning the truth value or believability of the findings)l6 in the text were achieved through the use of triangulation of data sources (multiple participants), a team of researchers who were all involved in interviewing, transcribing and cross-checking the data analysis, and allowing reflexivity (conscious reflection on one's subjective engagement in the research process), debate and shared insight. Member checking was done with three of the participants by presenting the findings to them in order to verify the researchers' understanding of the data gathered.

FINDINGS

Five themes emerged from the data analysis and are described together with supporting quotes. A summary of themes, sub-themes and categories is presented in Table II on page 55.

Theme One: Why am I where I am?

In this theme, participants' unique stories highlighting their perceived current involvement in gangs are described.

Wayne (aged 17 years) joined a street gang at the age of fourteen when he committed his first murder. At the age of sixteen he had already been detained in prison, where he was recruited to join one of the notorious Number gangs. The Number gangs are notorious, powerful prison gangs in South Africa identified as 26's, 27's or 28'sl7. Wayne asserted that belonging to a gang was a choice that was in his best interest, as the gang could offer him resources and protection. However, it came at a price, as once one is initiated into the gang the only way to leave is through death or by giving one's life to God through religion. It was clear that he experienced feelings of exhilaration at being in a gang and had taken a keen interest in the history and workings of the gang. He perceived himself as "climbing the ranks". Although he explained that he initially joined the gang as a means of taking revenge on members of other gangs, Wayne soon found himself engrossed with the idea of having his own money. This particular street gang mostly earned their money by either smuggling drugs or committing murders. He proved that he was not afraid to carry out violent acts. He explained that staying with the gang meant he was safe, and that going back home would be futile as he had enemies.

"Your enemies will still want to kill you. There's no use going back to your mother now". (Wayne)

Rozen (aged 17 years) was exposed to gang culture from an early age as his father belonged to a street gang. He perceived himself as being at a "crossroads" in life because although he was soon to be transferred to prison (when he turned 18), on account of having learnt about God he wanted to break away from any involvement and association with gangs. This resulted in his current state of uncertainty and confusion.

"I told the neighbours that I am now finished with this."(Rozen)

Aubrey (aged 17 years) was lured into the world of gangs by a gang leader living in the same neighbourhood. Aubrey, naive in his belief that the gang leader offered him drugs that would help him become clever and improve his soccer, was soon addicted to methamphetamine and mandrax. His substance abuse resulted in his dependence on the gang leader whose wishes Aubrey was forced to execute. He perceived himself as "trapped" as previous attempts at escaping the gang were unsuccessful and his life had been threatened.

"I used to run from him, went to the club, so he searched for me, he said he would kill me." (Aubrey)

Dylan (aged 16 years) endured many hardships growing up including being abused along with his older brother at the hands of their alcoholic father, observing his father use drugs, and later, watching his brother whom he adored, become addicted to drugs and run away from home. Dylan became involved with gang members to "belong" and started to engage in criminal activities. During the course of being sentenced at the Youth Centre, he made the conscious decision to "transform" his life by breaking away from the gang and making amends towards his family. He wanted to raise awareness about gangs and the lifestyle in order to deter youth from becoming involved.

"I'm not going back to the street. I'm going to do what I must."(Dylan)

Theme Two: To strengthen the camp

Becoming a gang member resulted in the assumption of new occupations and roles. Participants frequently referred to doing things that would impress, and promote the interests of the gang, in order to "strengthen the camp". This theme focuses on the occupations of gang members. Spending time with the gang, talking together, or generally being idle allowed gang members to observe movement and activity on their territory and plan activities.

"We sit there. We watch other little groups, who goes out. Do you see? We just watch those people in a place." (Aubrey)

Selling drugs was considered to be a business and was called "smokkelling" [smuggling]. Although by engaging in this occupation they were at risk of being caught and arrested by the police, the money they gained was considered worth the risk. The trade of drugs was considered in very business-like terms. The participants explained how they were continually in the process of obtaining money to buy drugs, selling the drugs and then buying more drugs or buying guns with the profit they had made. Gangs competed for control over territories so that they could sell drugs there, thus getting more money and power over the area.

"We have our block where we sell our drugs and stuff. The others, they will come here and try sell drugs. They will get your customers, then your business will go down." (Wayne)

Participants explained that using substances was an occupation they had engaged in regularly. Due to the fact that gangs are distributors of drugs, gang members have ready access to alcohol and drugs. Participants spoke about sitting with other gang members and using substances. They invited friends, girlfriends and younger school children to smoke with them. Eventually this led to many of them becoming addicted to drugs, which kept them dependent on the gang.

"I smoked buttons [mandrax] with him [the gang boss]. Then he said he sells the stuff, I can go stay with him. The drugs, you can smoke them the whole night. You see, you don't say no, then you smoke." (Aubrey)

The shared occupation of using substances influenced their thinking and was directly related to becoming involved in the other occupations of the gang including robbing people and fighting other gangs. Participants spoke of being "drugged up" and not being able to think, thus doing what other gang members told them to do.

"The buttons make you think, hey, I have a gun with me, I'll just kill somebody. I'll shoot him." (Rozen)

Robbing people was considered a way to gain money for the gang to buy drugs or weapons. The participants described different forms of robbery, ranging in scope from grabbing ladies' bags to armed robbery at shops.

"But sometimes, maybe you get a shop that makes lots of money, fifty, sixty thousand. We talk with each other, yes we can do that." (Wayne)

Killing and being killed is an everyday reality in the lives of gang members, and was identified as a common occupation for all of the participants. Most of the participants mentioned that killing someone from the enemy gangs was often considered necessary to prove one's determination to be initiated into the gang. Gaining a reputation as someone who has committed murder also increased the respect received from other gang members. One of the participants compared the conflict between the gangs in his area with war, and the opposing gangs were seen as enemies. In this light, the participants considered the continual fighting and killing as justified.

"Then I just drew, then I shot the first one (motions taking a gun out of his jacket and shooting someone). First one is dead already. Then I took the gun and shot the second one in the head." (Rozen)

Owning, caring for, and using, a weapon was an important occupation. Participants described how they felt stronger and less vulnerable when they were carrying guns, and gained a sense of mastery through proficiency in this occupation.

"It's cool man, playing with the guns, putting the bullets in, cleaning the guns, testing the gun, maybe shooting in the sky, you learn everyday something new. " (Wayne)

Securing places where the police were unlikely to find their weapons was important. One participant described how he stored the gang's weapons in a number of different locations, usually in the homes of people who were not involved in gang activities themselves but who would benefit from the gang through for example, being protected from other gangs, or receiving transport to hospital if a family member was ill.

Theme Three: Attraction to gangs

This theme highlights the needs that were met through gang-related occupations. Poverty and "broken homes" contributed to the participants' decisions to join gangs. Belonging to a gang gave the participants an identity, as well as social and financial support, which continued even while they were at the Youth Centre.

"You feel part of something, before the gang you were like no-one, you were just a boy. They [the gang] will be happy to see me 'cos they phone me every-day, when I go to court, they also in court for me, they respect me. They also pay for my lawyers, if I get the bill they pay the

bill." (Wayne)

Being in a gang gave the participants access to money, and this was a tremendous incentive to remain engaged in gang-related activities. They enjoyed getting paid after doing a job as they could buy expensive shoes and jewellery or take money home to their mothers.

"It's a nice life, every-day you have money, new clothes. The best thing of being in a gang is when you get paid (smiling). I like money, I don't want to walk with no money in my pocket." (Wayne)

Belonging to a gang enabled the participants to be independent. They valued the freedom to do what they wanted without interference from authority figures such as parents. The financial income gained from selling drugs made it possible to engage in activities that they enjoyed, like going to parties or using drugs.

"In our gang we don't have a boss. We don't sell drugs for somebody else, we decide what we do with the money. You don't have people nag you, you must stand up! You must clean! You must eat! There we just men, we do what we want. We want to be up whole night, drink, have a party, no-one's gonna tell us what to do." (Wayne)

Wayne expressed that there was a fascination and a thrill attached to violence and killing people. He associated gang violence with feelings of excitement and power.

"I think that time when I did my first murder and killed someone, it almost felt like fun shooting, but he's running then you kill him, then I want to do it again. To tell you the truth, I like shooting people, especially my enemies." (Wayne)

Theme Four: It's difficult but it's life

In this theme, the influence of gang-involvement on other occupations is described. Belonging to a gang is a lifestyle that affects all facets of the individual's life. The gang members are no longer seen as individuals or "frans" [outsiders] but as "ndoda" [men] who belong to the "kamp" [camp] or "troop". This is seen as an honour and a privilege, but it comes with responsibilities and expectations, and has a price.

Once participants were associated with gangs and adopted the identity of a gang member, their roles and interactions at school changed. They needed to portray the image of a "sterk bennie" [tough guy] and explained how they used substances at school, carried weapons with them to school, and got involved in fights. Wayne explained that he was expelled from his school after he stabbed a fellow learner. This incident further alienated him from society and cemented his decision to join the gang.

"I did stab the boy. Four times. And the school opened a case against me. And they did say I'm not welcome there any more, I can't come back." (Wayne)

Eventually participants dropped out of school but all expressed regret about this. When probed about the type of future they envisioned for themselves, the participants expressed that they wanted to pursue careers as policemen or lawyers. They realised that in order to do this they would need to complete their schooling. Thus, although they were "out of school" because of their involvement in gangs, they dreamed of being able to return to school.

"I would like to do evening classes." (Dylan)

Participants talked about not being able to play sports such as soccer any longer, as being part of a gang meant that they could not move around freely in their communities due to rival gangs occupying certain territories.

"I don't play sport because the sport field is in the middle by the Americans [gang], I can't go play sports there. That will be the easiest way to catch you, playing sport. Afterwards you are tired and then they get you." (Wayne)

Being part of a gang influenced the participants' relationships with girls even though some of them liked having gang members as boyfriends.

"Most girls like you being in a gang, not having a boyfriend who's scared, who gets robbed in front of them, they feel secure if you with them. You can stand [up] for her."(Wayne)

As they were affiliated to one specific gang, they were not allowed to engage with just any girl. If the girl they liked had a brother who was part of a rival gang, this was seen to be antagonistic. Territory played a big role in this as they were no longer allowed the freedom to go wherever they chose. Aubrey said that if he wanted a girlfriend she would have to live far from the gang so that they would not know about her, because the boss would rape the other gang members' girlfriends.

"Aaah (shaking head) I took her (motioning far away). Take her there, there... another place. I don't want to go to him [gang boss]. I know how he is. He just takes from the groupies [gang member's girlfriends]. He knows the troop, he smokes, he's here with you... He takes another girl. I don't like that." (Aubrey)

Belonging to a gang not only had negative implications on gang members but also their families. Not being able to engage with their families affected their relationships, particularly with their mothers. Mothers were important to the young men. Strong emotions were evoked when the participants discussed their relationships with their mothers. Participants felt that this was the only relationship in which they received love and acceptance regardless of what they did. All of the participants' mothers tried to extend love to them in different ways. However, because the gang demanded their loyalty to the exclusion of their mothers, they were estranged from their mothers. Thus, each participant's relationship with his mother was negatively affected by his engagement in the gang.

"The most difficult was with my parents. All the time, when I walk with the people [the gang], then my mother asks who are these people? What are they looking for?" (Rozen)

Theme Five: Threshold into Manhood

This theme describes the participants' perceptions that boys become men through their gang involvement. It was evident that street gangs progressed into Number gangs and that boys became men by becoming part of a Number gang, which was perceived as prestigious.

"But being a '28' [Number gang] is not like a gangster that fights. You must think, you on your own. You're a grown man now. Must think like a grown man not like a laaitie [small child] anymore." (Wayne)

The participants felt that growing up and becoming men meant that they needed to be prepared to do anything including taking the fall for gang leaders. They explained that each street gang had its own set of rules which needed to be obeyed without question, thus proving they were men.

"He [gang leader] did that stuff - smuggling. If the police come, he says it's my stuff, it wasn't his stuff. The rules say you mustn't talk about his things, what happens there in that group." (Aubrey)

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to better understand young men's motives and reasons for belonging to gangs by exploring the meaning and purpose of gang-related occupations.

Meaning of occupations related to being a gang member

In theme one, it was evident from the participants' experiences and life stories that each individual had a unique perception of his involvement with the gang, and this played a key role in the meaning given to his gang-related occupations. For example, when Aubrey's story is compared with Wayne's story, Aubrey's perception is that he is "trapped" in the gang and he feels powerless to resist the domination of a gang boss. By contrast, in Wayne's story of "climbing the ranks", he has the perception of exerting power over his environment through his reputation and status within his gang. These two stories highlight the different meanings that gang involvement had for these two young men. However, for all participants, their gang involvement shaped the occupations in which they engaged.

In the themes "To strengthen the camp", "Attraction to Gangs", and "Threshold into Manhood", the participants' perceptions of gang-related occupations were described. These occupations included sitting around with the gang, using and selling drugs, robbing people, fighting rival gangs and killing people, and owning guns. All of these occupations served to strengthen the camp and show allegiance to the gang. From the theme "Attraction to gangs", it is possible to identify elements of the participants' physical and socio-cultural environments that contributed to their decision to embrace the gang lifestyle. Their involvement in gangs provided access to social support, material resources, independence, and met the need for thrills and excitement. It was evident that prior to joining the gangs, the participants perceived their home environment as being less desirable compared with the environment within which the gang lived and socialised. Within the context of the poverty in their communities, gang-related occupations were perceived as providing access to an abundance of drugs and money. These findings are supported by Jenson18 who proposed that joining a gang brought promises of money, fancy cars and easy access to girls.

Purpose of occupations related to being a gang member

The young men engaged in gang-related occupations with a specific purpose - or outcome - in mind. The themes "Why I am where I am", "To strengthen the camp" and "Threshold into manhood" provide insight about what the young men perceived to be the purpose of their engagement in gang-related occupations. Although the purpose behind each participant's gang involvement was subjective, the central purpose of engaging in gang-related occupations was to strengthen the gang, prove manhood and for survival. Each participant held a different status and position, and the purpose of their occupational engagement was linked to the status they aimed to achieve within the gangs.

The purpose of Wayne and Rozen's occupational engagement related to their future goals. Wayne sought status and protection and found that these needs were met by belonging to the gang. His story "Climbing the ranks" highlighted two very important aspects that related to his progressive journey deeper into the culture of gangs: firstly, to seek respect and gain rank to develop status within the gang; and secondly, to be in control of his environment. Thus he gained power over, and protection from, his enemies. Rozen, in his story "Crossroads", elaborated on being accepted by his peers and acknowledged by his father. His search for acceptance in the gang created this space. The purpose of Aubrey and Dylan's involvement in gangs was about trying to survive in their current situations. Aubrey felt "trapped" by, and coerced into, gang culture and feared for his safety. Riddled with fear, he engaged in the gang-related occupations that were required of him with the purpose of surviving. Dylan's story illustrates his move towards deciding to leave the gang and "transform" his life. For him, purpose was achieved through his efforts to leave the gang to gain a sense of fulfilment in his life.

Part of the young men's involvement in gangs can be explained by examining their perceptions of how boys become men. This rite of passage is most evident in the theme "Threshold to manhood". There are strong parallels between Zdun's19 study conducted in the lower socio-economic areas of Brazil and Russia, and the present study. Zdun19 explains that men find it vitally important to establish an image of masculinity, so derived by defending their honour and that of others, particularly their mothers. Furthermore, the way in which people deal with conflict is an important occurrence and custom of street culture, such that those who seek to be treated with respect should not show any weakness in their daily lives, and in defence of their reputations are compelled to react aggressively towards all challenges they face. The young men in Zdun's19 study required two things: friends with whom a strong sense of solidarity was shared, and friends who could protect one from rivals. This is evident in the current study, particularly in the theme "To strengthen the camp" where the purpose of most of the occupations was to maintain the bond between gang members, and protect one another and their territory.

Influence on other occupations

It was evident that gang involvement came at a price as participants recognised that they were no longer able to engage in previous occupations and roles including schooling, leisure activities and relationships with mothers and girlfriends. It is possible to understand the influence of gang involvement on other occupations by exploring the participants' roles and routines. Roles are defined as a 'set of behaviours expected by society, shaped by culture, and may be defined by the person'20643. Clearly, due to their gang-related occupations, the participants were deprived of engaging in meaningful roles such as being sons and boyfriends. Routines are defined as established sequences of occupations or activities that provide structure for daily life20. It was evident that the young men were not able to have routines as the predictability would render them vulnerable to being targeted by rival gangs. Not being able to have routines affected their ability to engage in occupations such as schooling and leisure.

Occupational deprivation occurs when people are denied opportunities to participate in meaningful occupations due to factors beyond their control21. Clearly, gang-involvement prevented the young men's ability to engage in pro-social occupations, roles and routines that were meaningful to them. Participants' perceptions that gang involvement meant survival, escape from poverty and difficult family circumstances, and manhood, may indicate that the young men had little choice but to join gangs. Occupational choice can be limited by historical, political and socio-economic factors22. In a study of maternal alcohol consumption in a low socio-economic, rural community in the Western Cape, Cloete2338 introduced the concept of 'imposed occupation' which is the 'continuation of occupations that are not of choice, but rather as a result of structural (cultural, economic and political) entrenchment'. In the current study, the young men's involvement in gangs and related occupations may be regarded as an example of imposed occupation, due in part, to limited occupational choice, with occupational deprivation being the result. However, this notion needs to be explored in future research.

There was one main limitation in the study. Although the plan was to interview each participant twice, follow up interviews with two participants could not take place due to their unexpected transfer from the Youth Centre.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PRACTICE

In this descriptive qualitative study, the meaning and purpose of young men's involvement in gang-related occupations and the influence on other occupations were explored. The study is important because occupational therapists in settings such as forensic units, psychiatric hospitals, substance rehabilitation centres, youth care centres, community settings and schools will more than likely work with young men who are, or have been, involved in gangs. Understanding gang-related occupations assists occupational therapists to plan relevant programmes that interrupt the negative cycle of gang involvement, and support young men's disengagement from gangs and reintegration into the community. Programmes should focus on supporting the transition to pro-social occupations and choices, and the acquisition of successful adult roles through pre-vocational and vocational skills training; exploration of, and participation in, healthy leisure occupations; improving social, interpersonal and communication skills; and community living skills such as parenting skills.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors extend their appreciation to the four young men who shared their life stories with us and to the Centre for supporting this study.

REFERENCES

1. Kinnes I. National and local trends: Urban street gangs to criminal empires. The changing face of gangs in the Western Cape, 2000. <http://www.iss.co.za/Pubs/Monographs/No48/National.html > (10 March 2011). [ Links ]

2. Dos Reis KM. The influence of gangsterism on the morale of educators on the Cape Flats, Western Cape. Unpublished Masters' Thesis - Education: Cape Peninsula University of Technology, 2007. <http://digitalknowledge.cput.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11189/1550> (27 August 2014). [ Links ]

3. Cooper A & Ward CL. Prevention, disengagement and suppression: A systematic review of the literature on strategies for addressing young people's involvement in gangs. Report to RAPCAN (Resources Aimed at Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect). Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council, 2007. [ Links ]

4. Ward CL. "It feels like it's the end of the world": Cape Town's youth talk about gangs and community violence. ISS Monograph Series, Number 136, July 2007. [ Links ]

5. Helen Zille State of the Province Address. <http://www.western-cape.gov.za/general-publication/state-province-address-2011> (3 March 2015). [ Links ]

6. Kynoch G. From the Ninevites to the Hard Livings gang: Township gangsters and urban violence in twentieth-century South Africa. African Studies, 1999; 58(1): 55-85. [ Links ]

7. Ward CL & Bakhuis K. Intervening in Children's Involvement in Gangs: Views of Cape Town's Young People. Children and Society, 2010; 24: 50-62. [ Links ]

8. Wegner L. Through the lens of a peer: understanding leisure boredom and risk behaviour in adolescence. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2011; 41(1): 18-24. [ Links ]

9. Law M, Steinwender S, Leclair L. Occupation, health and well-being. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998; 65(2): 81-91. [ Links ]

10. Nelson DL. Therapeutic occupation: A definition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996; 50(10): 775-782. [ Links ]

11. Whiteford G. Occupational Deprivation: Global Challenge in the New Millennium. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000; 63(5): 200-204. [ Links ]

12. Kronenberg F Algado SS, Pollard N. Occupational therapy without borders: Learning from the spirit of survivors. United Kingdom: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005. [ Links ]

13. Snyder C, Clark F Masunaka-Noriega M, Young B. Los Angeles street kids: New occupations for life program. Journal of Occupational Science, 1998; 5: 133-139. [ Links ]

14. Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 2000; 23: 334-340. [ Links ]

15. Henning E. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik Publishers, 2004. [ Links ]

16. Babbie E, Mouton J. The Practice of Social Research. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press Southern Africa, 2001. [ Links ]

17. Goyer KC. Prison Privatisation in South Africa: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities. Chapter 2: Imprisonment in South Africa. Institute for Security Studies Africa. Monograph No 64, September 2001. <http://www.issafrica.org/Pubs/Monographs/No64/Chap2.html> (18 February 2015). [ Links ]

18. Jenson S. Gangs, Politics and Dignity in Cape Town. USA: University of Chicago Press, 2008. [ Links ]

19. Zdun S. Violence in Street Culture: Cross-cultural Comparison of Yfouth Groups and Criminal Gangs. New Directions for Youth Development. 2008; 119: 39-54. [ Links ]

20. American Occupational Therapy AAssociation. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2008; 62(2): 625-683. [ Links ]

21. Townsend A, Wilcock AA. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: A dialogue. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 71(2): 75-87. [ Links ]

22. Galvaan R. Occupational choice: The significance of socio-economic and political factors. In G.E. Whiteford and C. Hocking (Eds.), Occupational Science: Society, Inclusion, Participation. West Sussex: UK: Blackwell, 2012: 152-162. [ Links ]

23. Cloete LG, Ramugondo EL. "I drink": Mothers' alcohol consumption as both individualised and imposed occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2015; 45(1): 34-40. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lisa Wegner

lwegner@uwc.ac.za