Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.45 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a7

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

OT student's experiences of stress and coping

Pragashnie GovenderI; Simangele MkhabelaII; Mbali HlongwaneIII; Kimara JaliIV; Chetna JethaV

IBOccTh (UDW); MOT (UKZN); CAMAG (ABIME); Lecturer, School of Health Sciences, UKZN (Westville Campus)

IIBOT (UKZN); Occupational Therapist, Standerton Hospital

IIIBOT (UKZN); Occupational Therapist, Osindisweni Hospital

IVBOT (UKZN); Occupational Therapist, LIFE Entabeni Rehabilitation

VBOT (UKZN); Occupational Therapist, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: It is well known that tertiary education is highly stressful for students, particularly in the medical and health science fields. Studies have indicated that occupational therapy students are no exception, experiencing stressors in many areas of their life.

OBJECTIVE: This study explored the sources of stress & coping mechanisms employed by all levels of undergraduate occupational therapy students within a four-year degree programme at a tertiary institution in South Africa, more specifically to determine the types and frequency of stressors and coping styles employed.

METHOD: A descriptive survey design was utilised using a demographic and stress survey and a standardised coping questionnaire. 101 undergraduate students enrolled for the year under review were selected via saturation sampling of which 99 formed the sample. Participants ranged between 17-28 years of age, the majority of which were English speaking females.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: Amongst first year students, personal stressors were the most significant overall stressor whereas academic stressors were the most highly ranked stressors in the second to fourth year students. Both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping was utilised by students. The results of this study provide a snapshot of a cohort of students' experience of stress and the coping mechanisms employed. This may be a starting point for student support services in identifying the presence of stressors and types of coping in order to explore more deeply the consequences of this on students' overall well-being and performance.

Key words: stress, coping, students, occupational therapy, health science students

INTRODUCTION

Stress is understood to not only be a universal phenomenon but also a universal experience, and the way in which people respond to and cope with stress differs1. Entry into tertiary education poses new challenges for students and the transition from school to university often brings with it new stressors, and requires adequate coping. Students are expected to handle academic stressors, including integrating academic and clinical workloads; personal stressors that involve 'juggling' the responsibilities of this phase of life and more general university-related stressors, like accessing resources and those relating to peers. Educational programmes in the medical and health science fields are geared towards producing skilled and competent graduates; however studies2,3,4,5 have shown that varying degrees of stress experienced by students may affect their overall functioning and performance. Whilst stress is considered a necessary part of life towards personal development, not all students are able to cope adequately. An example from our current context is a study undertaken with medical students from three universities in South Africa in which the presence of major depressive disorder, reports of suicidal ideation and prior suicide attempts were reported by the student's sampled6.

Anecdotally, the authors of this study noted within their occupational therapy (OT) programme, an increasing number of students being hospitalised during their student years, with stress-related states being the primary reason for admission. A high number of students were also reportedly on anxiolytic and antidepressant medication, with some students resorting to maladaptive behaviours, including substance abuse and para-suicides. Given these observations, and an assumption by the authors that students may have not been equipped to adequately cope with the demands of tertiary education, this study emerged as a starting point, to determine what stressed the students enrolled in a specific OT programme and what coping mechanisms were employed by students.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Lazarus and Folkman3 define stress as a particular relationship between the person and the environment, appraised by the person, as taxing or exceeding his or her resources, and endangering his or her well-being. A stressor can be considered a trigger that causes a stress response. However, all persons experience stressful situations differently, and there may not always be a negative reaction associated with the stressful situation4. If one views an event or situation as a challenge, it is more likely that a positive outcome will be achieved, whereas, if the situation was viewed as a burden or threat, it is more likely that a negative outcome will be reached5.

The studies conducted over the last two decades in Australia1, United Kingdom7, India8, Nepal9 and Zimbabwe2 provide evidence that tertiary education is highly stressful and that tertiary students face stressful demands in their student life. It has also been widely reported that health science students are exposed to and experience high levels of stress6,8,9,10. The challenges faced by OT students appear no different to other health science students.

From a review of the literature the authors identified stressors experienced by students as falling into one of three broad categories, namely personal, academic and university-related stressors. Personal stressors experienced by students are well documented1,2,7,8,9,10,11,12 and include physical problems or impairments, family difficulties, financial difficulties, access to resources, social issues, managing relationships and transitioning through adolescence to adulthood. Academic stressors experienced by students include high academic expectations, rigorous class schedules, integration of classroom and clinical learning, tests and examinations, the amount of class work and poor grades, time management, clinical fieldwork, relationships with supervisors, amongst others8,13,14,15,16. University related stressors included adjustment to university life, access to resources e.g. library resources and peer or colleague conflict17,18. Due to the continually changing nature of the university environment students can potentially experience high levels of stress that can affect their health and academic performance.

Coping has been defined as a process of constantly changing ones cognitive and behavioural efforts in order to manage specific external or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person3. Coping strategies are considered those specific efforts, both behavioural and psychological, that an individual employs to master, reduce or minimise and tolerate stressful events9.

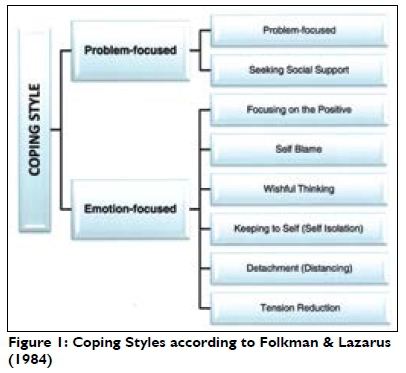

Lazarus and Folkman3 provided a useful theoretical framework that described the process of coping. A number of studies researching stress and coping have been conducted since the theoretical framework was first introduced and presented1,4,7,8,12,19,20,21. Lazarus and Folkman3 describe eight broad types of coping strategies that individuals may employ in stressful situations. These eight types of coping are further classified into two broad categories, viz. problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies. Problem-focused coping strategies include seeking social support and problem-focused coping. Emotion-focused coping strategies include focusing on the positive, self-blame, wishful thinking, keep to self, detachment and tension reduction (Figure 1).

Both types of coping strategies are utilised by individuals in stressful events and will be discussed briefly.

Problem-focused coping is when the individual interacts with the environment through direct action, problem solving and active decision making3. Holland22 added that the direct action involves changing the situation/event or changing the self in order to remove the source of stress. Overall, problem-focused coping strategies are aimed at reducing the demands of the situation or stressor by expanding the resources for dealing with the stressor3 and are often used when the person believes that the demand/stressor is changeable3.

Problem-focused strategies and positive thinking methods of coping are considered to be adaptive coping strategies which reduce stress4. Problem-focused coping strategies3,22 include:

φ Identifying, planning how to confront the stressor and planning one's coping efforts. The individual engages in problem solving behaviour.

φ Seeking social support.

φ Taking assertive action, analysing the situation to arrive at solutions and take direct action to correct the problem.

φ Trying to change the environment or by focusing on something unrelated to the stressor in order to change their mind or avoid thinking about the situation or stressor.

Previous studies1,2,9,11,23 highlight that coping strategies used by health science students are either problem-focused such as problem solving, planning, acceptance, active coping, managing their time, seeking information and sport and recreational activities or they employ emotion-focused strategies such as tension reduction strategies such as exercising, balanced diet, getting enough sleep, and engaging in constructive leisure activities strategies.

Emotion-focused coping strategies are all the efforts directed at alternating emotional responses to stress7. The efforts are directed at minimising the negative effects of the stressor, therefore the individual feels better but the problem is not solved22. Thus emotion-focused coping strategies are aimed at reducing the impact of the perceived stressor if the stressor cannot be altered or avoided, or if the individual perceives the stressor as extremely threatening, unchangeable and uncontrollable.

Emotion-focused coping strategies2,3 include:

φ Avoidance, loss of hope, minimisation, distancing, selective attention and positive comparisons,

φ Positive reappraisal and rationalisation,

φ Smoking, substance abuse, sleeping and eating

φ Wishful thinking and self-blame

φ Denial, social withdrawal and avoidance.

Emotion-focused strategies such as avoidance and negative thinking in response to a stressor are considered to be maladaptive methods of coping4. When coping with stress, focusing on emotions can negatively impact an individual's adjustment to his/her situation5 and avoidance coping styles may lead to psychological distress4,5. Dependent on the situation, a particular coping response may be effective for some individuals while it is detrimental to others5. Studies have shown that there is a link between emotion-focused coping and symptoms such as depression and anxiety24,25. Although these methods of coping may reduce an individual's stress levels, it promotes long term ill health4. Additionally, the consequences of maladaptive coping may lead to decreased self-esteem, increased alcohol consumption and smoking, reduced functioning of the immune system26, increased suicidal tendencies, poor academic performance and drop outs27. A study done in a medical school in Pakistan indicated that most students presented with symptoms of low moods, inability to concentrate, short temper, change in sleep patterns and loneliness and others presented with headaches and stomach-aches28. In a local study done in Pretoria6 students reported the use of medication to alleviate their depression, regardless of whether a prescription was obtained.

METHOD

A quantitative descriptive survey design was used in this study. The target population comprised all undergraduate students, in all four years of study, enrolled in an OT programme at a tertiary institution in South Africa in 2011. Saturation sampling was thus employed with the target population comprising 101 students.

Permission was granted by the relevant institutional ethical committee in addition to gatekeeper permissions from the relevant Dean and head of department.

A covering letter and consent forms were distributed to all the OT students within the first week of the second semester of the 2011 academic year with an invitation to attend the specific sessions in which data collection had been arranged. Informed consent forms were collected prior to questionnaires being distributed by the academic development officer (ADO) assigned to the discipline of occupational therapy. The questionnaire was handed out to the class groups during these pre-arranged sessions. Students were given 45 minutes in which to complete the questionnaires, which were returned to the ADO at the end of the session. No identifying data were requested so that anonymity was maintained.

Data was collected via a demographic questionnaire (A), a descriptive stress survey (B) and the Ways of Coping Checklist19,21 (C). Sections A and B were developed by the authors. The demographic questionnaire (A) covered the participants' year of study, age, gender, home language and their current living situation. The stress survey (B) consisted of 17 items exploring stressors ranked on a 5-point likert scale (Never, Almost never, sometimes, fairly often, very often). Of these 17 items, seven were related to personal stressors (family issues, relationship issues, other personal/social issues, health concerns, transport related stressors, accommodation related stressors, financial issues); another seven were related to academic stressors (tests and examinations, time management, lecture content, practical fieldwork, demands at each level of study, conflict with supervisors and lecturers, and language barriers) and three were related to university-related stressors (adjusting to university life, peer/colleague conflict and library resources). The inclusion of these stressors and the grouping into the three categories were based on stressors indicated in the literature as described in the literature review.

Section (C) consisted of the 'Ways of Coping Checklist' (Student Version)19,21. This 66-item, validated, self-report measure covers a broad range of cognitive and behavioural strategies people generally use to manage stressful demands19,21. Subjects are required to respond using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (does not apply and/or not used) to 3 (used a great deal) as to the extent to which the item was used in the specific stressful encounter21.

The questionnaires were sent to a pilot group of 10 students (in any year of study) within the discipline of Speech Language Pathology and Audiology to highlight potential ambiguities prior to the main data collection process. No changes were necessary following the pilot study.

Data Analysis: The Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) version 19, was used to analyse the data. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the main source of stress experienced by the participants as well as the frequency of each stressor, in addition to the most frequent coping styles employed by the participants as a collective group as well as per year of study.

RESULTS

The sample population consisted of 101 students. The overall response rate was 99% with a total of 99 questionnaires completed. One student was unavailable and one questionnaire was not considered for analysis due to missing data.

The results will be highlighted as follows. Firstly an overview of the demographic profile (A) of the sample is provided, followed by the reporting of stressors identified in this study from results of the stress survey (B). This is highlighted by findings pooled within the three categories of personal, academic and university related stressors, followed by a description of each of the specific items for the overall sample (n=99). The results are concluded with a description of the different coping strategies employed within the sample.

Demographic Profile of OT Students

Of the participants, 91.9% were female and 8.1% were male. The mean age of the respondents was 20.5 years with a range of 17-28 years. 29.3% of the sample were in their first year of study, 29.3% in second year, 24.2% in third year and 17.2% in fourth year. The majority of the participants in this study (75.8%) spoke English as a home language. Other first languages spoken by the participants in the study included isiZulu (15.2%), siSwati (3%), Afrikaans (2%), isiXhosa (1%), seSotho (1%) and Tshivenda (1%) with 1 student (1%) not specifying his/her first language. The majority of students (62.6%) was living at home with parents or guardians; 18.2% were living in an on-site campus residence, 17.2% were living in private accommodation off-campus and 2.0% boarded with friends or family. There were no statistically significant relationships between the demographic variables and stressor and coping employed.

Types of Stressors Experienced by OT Students

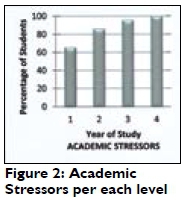

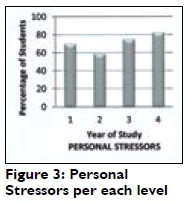

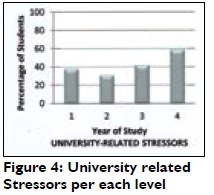

A summary of the overall findings are presented in which the three categories of academic (Figure 2), personal (Figure 3) and university-related stressors (Figure 4) are depicted.

Generally, the results reflected the highest percentage of students with stressors as the fourth year students, viz. academic (100%), personal (82.4%) and university-related stress (58.8%) as compared to the other levels of study. This was followed by third year students, where 95.8% reported academic stressors, 75% personal stressors and 41.7% reported university-related stressors. A smaller percentage of students in first year as compared to third and fourth year students, reported academic stressors (65.5%), with the least percentage of second year students reporting personal (58.6%) and university-related stressors (31%) as compared to all other levels of study.

Figure 5 on page 37 provides more specific detail on the frequency of each of the individual stressors as experienced by the total sample (n=99).

Coping Styles Employed by OT Students

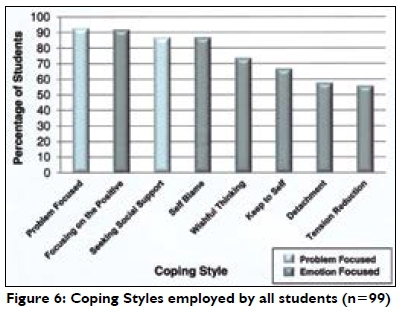

The Ways of Coping Checklist19,21 has 66 items that are divided into specific coping strategies that fall either into problem-focused coping or emotion-focused coping (described in Figure 1). Overall problem-focused coping was utilised more frequently by students on average (89.9%) as compared to emotion-focused coping (72%). Specific coping strategies employed by the students (Figure 6), ranked in descending order were as follows: problem focused coping (92.9%), focusing on the positive (91.9%), seeking social support (86.9%), self-blame (86.9%), wishful thinking (73.7%), keeping to self/self isolation (66.7%), detachment/distancing (57.6%) and tension reduction (55.6%).

DISCUSSION

This study reports the findings of stressors and coping in a cohort of students within an occupational therapy programme. Overall, academic stress was reported more frequently as compared to personal stress amongst second, third and fourth year OT students. This is supported by studies by Kauser23 as well as Kumar and Jejurkar8 who found a positive correlation between academic workload and perceived stress among students in their respective studies. The most common academic related stressors in this study included tests and examinations, time management and the demands of each level of study (Figure 2). These findings are supported by other studies8,9 in which the vastness of the academic curriculum and frequency of examinations were amongst the highest experienced stressors as well as stress related to time management14. Academic stress also appeared to be reported by a greater percentage of students in higher levels of study (i.e. third and fourth year students) which may be as a result of the increasing demands placed upon the students at each level of study. A greater number of fourth year students ranked academic related stress higher than other stressors as compared to the first, second and third year students (Figure 3). This may additionally be accounted for by demands placed on the students to meet the expectations of the fourth year requirements in terms of close to full time practical fieldwork, research requirements as well as other academic commitments.

Personal stressors were experienced by students in all levels of study, with the greatest percentage of students in fourth year reporting stressors related to their personal life. Personal stressors experienced by students remain well documented in the literature 1,2,7,8,9,10,12,13

University related stressors were the least named stressor reported by all students. University related stressors included adjustment to university life, library resources and peer or colleague conflict. A greater percentage of fourth year students experienced university related stress, specifically with respect to access to library resources or study material and conflict with peers, as compared to the first, second and third year OT students. Students in fourth year are placed at practical fieldwork sites for extended periods of time and as a result are not on campus to access library resources or study material. Additionally, students are completing their honours level research projects and are in contact with their peers for a large part of their day which may lead to frustration and conflict with each other.

The most frequently utilised coping strategies by the OT students were problem focused coping, focusing on the positive and seeking social support and the least utilised being keeping to self, detachment and tension reduction.

Problem focused coping is utilised through students making a plan of action, weighing out different solutions and putting a plan into action. Students are said to potentially use this type of coping strategy when they have gained knowledge and greater clinical experience which may be utilised in identifying and handling problems16. Other authors of studies done with students9,23 found that taking action and planning formed the top three highly used coping strategies utilised by these students as well as solving specific problems and seeking information. Seeking social support was utilised by 86.9% through praying, talking to someone and asking for advice. In a student's life, support through family and friends may be the most desired. Pfeifer and colleagues14 in their study done on OT students found that many students utilised friend and family support systems as a coping strategy and Lo1 in a study on nursing students indicated that the students coped better through social support.

Emotion-focused coping most frequently used by students in this sample included focusing on the positive, seeking social support, self-blame, wishful thinking and keeping to self, with detachment and tension reduction reported less frequently as compared to the other strategies. Focusing on the positive was utilised by 91.9% of the OT students. Looking for the silver lining, trying to look on the bright side of things and rediscovering important things in their life are examples of this coping style. 73.7% of students engaged in wishful thinking in an attempt to cope with stress when they may have used daydreaming, having fantasies or hoping for a miracle. In a study with nursing students in Hong Kong, staying optimistic was found to the second highest utilised coping strategy6. In a study17 in Iran, authors highlighted that nursing students frequently used daydreaming as a coping strategy. Difficulties experienced by the students in this study may have been seen as learning experiences with the promise that things would get better, given that the life of a student is filled with both rewarding and challenging experiences. 86.9% of the students utilised self-blame when faced with a stressful situation. In a student's life, this may be due to poor time management and procrastination, having not prepared adequately for tests and examinations as well as conflict with supervisors and peers13,14. 66.7% of the students keep to themselves when dealing with stressful situations, for example keeping feelings to themselves, avoiding being with people in general or keeping others from knowing how bad things are. Detachment was employed by 57.6% of the students when confronted with a stressful situation. Students utilized these through trying to forget the situation, going along with fate or going on as if nothing is happening. This may be due to a high amount of students utilising positive thinking as a coping strategy. Other studies done in Nepal9 on medical students and Australia1 on nursing students' utilised avoidance and denial through an attempt to reject the reality of the event as though it never existed to deal with their stressors. Tension reduction was employed by the fewest number of students. Tension reduction methods of coping include positive methods such as relaxation and exercise and negative methods such as substance use. The study1 with nurses in Australia highlighted that nursing students utilised tension reduction as a method of coping and these included smoking, drinking, crying, meditation and yoga. Students often complain of not having adequate opportunity for social and recreational activities given their demanding schedules, which may have contributed to fewer students using this strategy for coping.

CONCLUSION

This descriptive study was conducted in the pursuit of determining stressors and coping strategies utilised by a cohort of OT students within an undergraduate programme. Amongst the sample, there was a high percentage of students who reported stress related to academic work within all four levels of study. Problem-focused coping strategies were mostly utilised by the OT students through facing the stressor and attempting to reduce it through direct action of making a plan and implementing it, with a number of emotion-focused coping mechanisms also being employed. Students' mental health and overall wellness are considered essential to cope with the demands of tertiary education and that of a health science programme. Anecdotally, the authors have observed an increasing number of students who are experiencing stress-related states requiring medical intervention. An assumption of the authors, in undertaking this study was to determine the type of stressors and coping in students in their programme in order to highlight potential markers that may be contributing to these observations. Perhaps this would be a starting point for greater exploration into the coping mechanisms utilised by students, identifying what may be adaptive and maladaptive to inform wellness and support programmes for students within health science programmes, given that stress in tertiary students and more specifically health science students remain well documented.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Mrs N Motala who assisted in the supervision of this project.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

PG. was the project leader and supervisor of the study and was responsible for the conceptualisation of the study, as well as drafting and review of the manuscript. M.H., S.M., K.J. and C.J. were final year students who conducted the study and assisted in the first draft of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Lo R. A longitudinal study of perceived level of stress, coping and self-esteem of undergraduate nursing students: an Australian case study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2002; 39(2): 119-126. [ Links ]

2. Kasayira JM, Chipandambira KS & Hungwe, C. Stressors and coping strategies of state university students in a developing country. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 2007;17 (1-2): 45-50. [ Links ]

3. Lazarus RS. & Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York:Springer Publishing Company Inc.,1984. [ Links ]

4. Shaheen F & Alam S. Psychological Distress and its Relational to Attributional Styles and Coping Strategies Among Adolescents. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 2010; 36(2): 231 -238. [ Links ]

5. Carver CS, Scheier MF & Werintraub JK. Assessing Coping Strategies:A Theoretically Based Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1989; 56(2) :267-283. [ Links ]

6. Van Niekerk L, Viljoen AJ, Rischbieter P & Scibante L Subjective experience of depressed mood among medical students at the University of Pretoria. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 2008;14(1): 27-31. [ Links ]

7. Robotham D. Stress among higher education students: towards a research agenda. Higher Education, 2008; 56(6): 735-746. [ Links ]

8. Kumar S. & Jejurkar K. Study of stress level in occupational therapy students during their academic curriculum. The Indian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2005; 37(1): 11-14. [ Links ]

9. Sreeramareddy CT, Shankar PR, Binu VS, Mukhopadhyay C, Ray, B. & Menezes RG. Psychological morbidity, sources of stress and coping strategies among undergraduate medical students of Nepal. BMC Medical Education, 2007; 7(1): 1-8. [ Links ]

10. Tucker B, Jones S, Mandy A & Gupta R. Physiotherapy students' sources of stress, perceived course difficulty, and paid employment: Comparison between Western Australia and United Kingdom. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2006; 22(6): 317-328. [ Links ]

11. Johari AB & Hassim IM. Stress and Coping strategies among medical students in National University of Malaysia, Malaysia University of Sabah and University Kuala Lumpur Royal College of Medicine Perak. Journal of Community Health, 2009; 15(2): 106-115. [ Links ]

12. Dahlqvist V Soderberg A & Norberg A. Dealing with stress: Pattern of self-comfort among healthcare students. Nurse Education Today, 208; 28(4): 476-484. [ Links ]

13. Nerdrum P Rustoen T & Ronnestad MH. Psychological Distress among Nursing, Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy Students: A Longitudinal and Predictive Study. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 2009; 53(4): 363-378. [ Links ]

14. Pfeifer TA, Kranz PL & Scoggin AE. Perceived stress in occupational therapy students. Occupational Therapy International, 2008;15(4): 221-231. [ Links ]

15. Spiliotopoulou G. Preparing Occupational Therapy students for Practical Placements: Initial Evidence. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2007; 70(9): 384-388. [ Links ]

16. Chan CKL, Winnie KW & Fong DYT Hong Kong Baccalaureate Nursing Students' Stress And Their Coping Strategies In Clinical Practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 2008; 25(5): 307-313. [ Links ]

17. Seyedfatemi N, Tafreshi M & Hagani H. Experienced stressors and coping strategies among Iranian nursing students. BMC Nursing, 2007; 6(1): 1-10. [ Links ]

18. Hamaideh SH. Stressors and reactions to stressors among university students. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 2011; 57: 69-80. [ Links ]

19. Folkman S & Lazarus RS. If It Changes It Must Be a Process: Study of Emotion and [ Links ]

20. Coping During Three Stages of a College Examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1985; 48(1): 150-170. [ Links ]

21. Folkman S & Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1980: 219-239. [ Links ]

22. Folkman S. Ways of Coping Checklist (WCCL). Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine, 2013: 2041-2042. [ Links ]

23. Holland K. A study to identify Stressors perceived by Health Science Lecturing staff within a school at a South African Univer-sity.2001:1-107. <http://hdl.handle.net/10413/5683> (Accessed 28 August 2015) [ Links ]

24. Kausar R. Perceived Stress, Academic Workload and Use of Coping Strategies by University Students. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 2010; 20(1): 31-45. [ Links ]

25. Dawson AE. Negative Coping Strategies Mediating the Relationship of Adolescent Attachment Classifications and Future Externalizing Behaviors. L. Starling Reid Undergraduate Psychology, 2009:1-42. <http://minerva.acc.virginia.edu/psychology/downloads/DMP%20Papers/Dawson-2009.pdf> (27 August 2015). [ Links ]

26. Mosley TH, Perrin SG, Neral SM, Dubbert PM, Grothues CA & Pinto BM. Stress, Coping and Well-Being among Third-year Medical Students. Academic Medicine, 1994; 69(9): 765-767. [ Links ]

27. Sarid A, Anson O, Yaari A & Margalith M. Academic Stress, Immunological Reaction and Academic Performance among students of Nursing and Physiotherapy. Research in Nursing and Health, 2004; 27(5): 370-377. [ Links ]

28. Shaikh BT, Kahloon A, Kazmi M, Khalid H, Nawaz K, Khan NA & Khan S. Students, Stress and Coping Strategies: A Case of Pakastani Medical School. Education for Health, 2004; 17: 346-353. [ Links ]

29. Folkman S & Lazarus RS. Manual for the Ways of Coping questionnaire. USA: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.,1988. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Pragashnie Govender

Private Bag X54001

Durban, 4000

naidoopg@ukzn.ac.za