Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.45 no.2 Pretoria ago. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/V45N2A8

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Students' fieldwork experiences of using community entry skills within community development

Nicola VermeulenI; Teneil BellII; Aneesah AmodIII; André CloeteIII; Taryn JohannesIII; Karen WilliamsIII

IBSc OT (UWC), MSc OT, (UWC); Associate Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, University of the Western Cape

IBSc OT, (UwC), MECI, (UP); Students in the Department of Occupational; Therapy University of the Western cape at the time that the study was carried out

IIIBSc OT, (UWC); Students in the Department of Occupational; Therapy University of the Western cape at the time that the study was carried out

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Community development has been identified as an approach that occupational therapists can use to make a unique contribution to the health of communities. There is however limited research that addresses the practical application that occupational therapists need to use when engaged in community development. This includes community development's most important phase of community entry which is defined as a prelude to any action that will take place in true partnership with the community

PURPOSE: This paper explores the experiences offinal year occupational therapy students using community entry skills during community fieldwork practice

METHODS: An auto-ethnographic approach was used to explore students' experiences of the use of community entry skills within community development. Data collected included the use of the students' reflective fieldwork journals, a narrative and a focus group. All data collected was critically analysed through a process of thematic analysis in order to explore the students' experiences of the use of community entry skills during community fieldwork practice

FINDINGS: The findings of this study highlight that the process of community entry is a subjective experience that requires mindfulness and awareness in becoming a part of the community. This allows professionals to interact with the community and its members and it gives rise to the understanding that one receives when working in a community

IMPLICATIONS: Recommendations are made regarding the support of and preparation of Occupational Therapists in the field of community development.

Key words: Community Development, Community Entry Skills, Fieldwork Education, Auto-ethnography

INTRODUCTION

According to McConnell1, community development is broadly defined as the practices of community advocates, involved residents and professionals working collectively towards building stronger and more resilient local communities by empowering individuals and groups of people through the provision of skills needed to effect change in their own communities. Literature on community development covers a wide variety of definitions because various social and intellectual traditions have contributed towards the advancement of community development practices2. Occupational therapy however defines community development as a "multi-layered, community driven process in which relationships are developed and the community's capacity is strengthened, in order to affect social change that will promote the community's access and ability to engage in occupations"3:319. Wilcock4:238 defines community development from an occupational therapy perspective as: "community consultation, deliberation and action to promote individual, family, and community-wide responsibility for self-sustaining development, health and well-being". In both occupational therapy definitions of community development, the early emphasis is on developing relationships and consulting with the community. However, in order for this to occur, action needs to be taken in order to bring people together and prepare them to work collectively. Tareen and Omar5

define this as community entry and state that it is a prelude to any action that will take place in a true partnership with the community. There is, however, a notable scarcity of literature about the process that health professionals engage in when involved in community development. More specifically there appears to be minimal guidance regarding the application of the primary step in community development which is community entry.

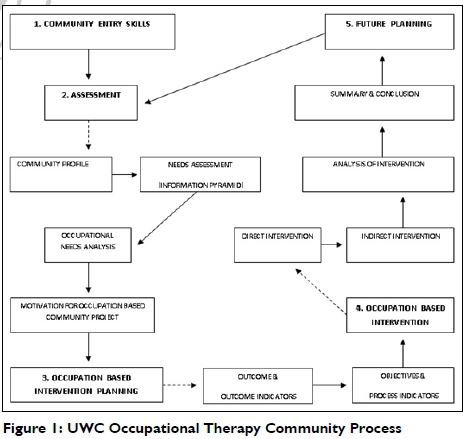

At the University of the Western Cape (UWC) in South Africa, final year occupational therapy students while in fieldwork practice in community settings, make use of the Community Process6 as a community development approach that allows students to focus on the needs of the community. As a point of departure, students have to undergo a process of community entry and community needs assessment and then perform a comprehensive needs analysis. This leads to the selection of a project in collaboration with the community. The project selected must take into consideration Health Promotion, Community Development and Occupation Enablement approaches. They then develop an intervention plan that includes the community resources they would use. This community fieldwork placement is compulsory for all final year occupational therapy students in which the main aim is for students to develop their understanding of the role of an occupational therapist in a community setting and to enhance their understanding of the occupational nature of communities.

This article will focus primarily on the first step (see Figure 1) of the UWC Community Process which is community entry. The greater research study was undertaken by five UWC undergraduate occupational therapy students as part of their research module in which the aim of the study was to describe how they as students came to understand the culture of a community through the use of community entry. This article will highlight one aspect of the research study in which the purpose will be to describe the five occupational therapy students' experiences of community entry within community fieldwork and to provide guidelines for the practical implementation thereof.

LITERATURE REVIEW

According to a document titled Community Development and Client Participation Approaches to Addressing Health Inequalities7, community development should be supported by values of social justice, self-determination, solidarity, collaborative working, participation and equality. Labonte8:260 proposed that community development is ".. .a process of organizing and/or supporting community groups in identifying their health issues, planning and acting upon their strategies for social action/social change, and gaining increased self-reliance and decision making power as a result of their activities". As such community development should strive to enable people to mobilise and develop their potential so that they are able to develop an ongoing ability to recognise and respond to their own problems.

In the last decade, the profession of occupational therapy has made significant changes in its approach to practice which has revolved around a shift from a focus on individualised treatment within a medical model to a comprehensive approach with a focus on health promotion and prevention9. Watson10 is of the opinion that in order to promote social development the four main areas that should be addressed are an enabling environment, employment, poverty alleviation and the eradication of social exclusion. She asserts that occupational therapy could significantly address these four areas if the profession adopted a population rather than individual perspective and embraced health from a promotive and preventative perspective. Community development has been described by various authors1,3,4,8 as a strategy that can promote social development through responding to the communities needs by emphasising empowerment and capacity building.

According to Lauckner, Krupa and Paterson11 there is limited research that addresses the practical application that occupational therapists need to use when engaged in community development. This includes community development's most important phase which is contact making12 (also known as community entry). This phase has three objectives which involve the community getting to know and accept the occupational therapist; the occupational therapist must get to know and understand the community and its circumstances; and lastly the community and the occupational therapist must collectively identify a need that can be addressed through a project.

Community entry is a sensitive process that requires an awareness and understanding of communities, interpersonal relationships and group processes. As South Africa is rich in cultural diversity, it means that working in community development requires a sensitivity and openness toward the community9. Duncan13:177 adds to this by stating that community entry requires the willingness to listen and learn rather than the intensity to make things better because of an assumed authority situated in academic knowledge and professional expertise.

Tareen and Omar5 propose five steps in order to gain entry into a community. These steps involve establishing dialogues with the community members; identifying community problems; discussing intersectoral issues; mobilising the community to take action; and establishing partnerships within the community. This process, according to Tareen and Omar5 is a gradual social process which mobilises communities to actively participate in their own social development.

Parasyn14 on the other hand proposes a different strategy of community entry by encouraging community developers on arrival and entry into the community to walk and not run through this process. She suggests that community developers walk through a process of community entry that she calls "be'ing" with the community using the skills of look, listen and learn. She defines this as a state of openness, observation, listening and sponging, questioning and passively engaging in all that is happening around you. Parasyn14 states that the best way to experience a community is to experience it first hand and that this stage takes time which may vary depending on the community. She further emphasises that it is critical for community developers to remember that as professionals, the experts in the community are the community members themselves.

METHOD

The study was based in the interpretivist paradigm with a qualitative research methodological approach and an auto-ethnographic design. An interpretivist view of social reality is that there are multiple realities and that truth is experienced and created subjectively through the phenomena being studied. Key characteristics of such studies are that the focus is on the meaning derived from the participants, the lived experiences of the participants as well as the process that they have experienced15. As is appropriate within this paradigm and also because the students own lived experiences of community entry within community fieldwork was researched, an auto-ethnographic design was used with a qualitative approach.

Auto-ethnography emerged from ethnography which is an approach to research that involves immersion within, and investigation of a culture or social world16. Within auto-ethnography the researchers become a part of the inquiry and use their own experience, which effectively produces new knowledge by a uniquely situated researcher17. Auto-ethnography does not have established research methods or a standard format to follow, thus allowing researchers to use their own experiences and providing the opportunity to address unanswered questions18. Therefore, as is expected within auto-ethnography, the students were both the participants in the study and the researchers of the study.

Participants and Research Setting

The participants in the study were five final year occupational therapy students placed in the community of Mitchells Plain, Cape Town, South Africa, for their community fieldwork placement. The duration of the fieldwork placement is seven weeks during which the students are expected to follow the steps of the UWC Community Process. As part of the research component of the undergraduate programme, these five students used their experience of their community fieldwork practice to explore their use of community entry skills within community development.

Mitchells Plain is a community located in Cape Town, approximately 20 kilometres from the city centre and has been in existence since the early I970's. The area is approximately 110, 2 km2 and is classified as majority urbanised area. Conceived of as a "model township" by the apartheid government, it was built during the 1970s to provide housing for victims of forced removal due to the implementation of the Group Areas Act19. Key challenges found in the area are gangsterism, high unemployment rates, high crime rates, social disintegration and a lack of community cohesion.

Data Collection

Within auto-ethnography many different data sources and collection techniques can be used. Data sources in auto-ethnography are not the typical sources and may vary extensively. These sources may include personal writing and reflection, stories from others, personal poetry, drawings, paintings, photographs, artifacts and metaphors18. Within this study the data sources used were the students' own daily fieldwork reflective journals, a personal narrative written by each student, and a focus group discussion.

Reflective journaling is a requirement of the undergraduate occupational therapy programme at UWC that is used predominantly with students who are undergoing a fieldwork component of the programme. As a result the final year students are required to write daily reflective journals during their fieldwork placements to demonstrate their learning and professional development. The reflective journals were used as a data source as they contained the students' immediate experiences of the use of community entry during their community fieldwork placement.

In addition students were then required to write personal narratives based on their own experiences, or a story of how they experienced community fieldwork practice. This approach offers multiple views of an account which potentially provides a richness and complexity while preserving the individual within the story16. The students' individual narratives were used as a data source as they contained the students' own insights about their experiences as they were compiled after the completion of the community fieldwork placement during the research process.

In the focus group discussion each student presented their personal narratives to each other and shared their thoughts regarding what each person had written. This focus group discussion was used as a data source as it provided direct evidence about the similarities and differences in the students' opinions and experiences15 of the use of community entry within community fieldwork. The focus group discussion was audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

All qualitative data were collected prior to the analysis to ensure that the students' personal narratives and their discussion were not influenced by analysing their reflective journals first. Narrative analysis was used to analyse the data which includes exploring terms of the broader political, cultural and structural context in the narratives16. This technique includes using codes, categories and themes and involves making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specific characteristics of messagesI5. As the study follows an auto-ethnographic design, the process of narrative analysis was undertaken by the students themselves. The five students collectively coded their reflective journals, their personal narratives and the transcribed focus group, sorted the codes into categories and then established themes.

FINDINGS

This section presents extracts of the data drawn from the students' reflective fieldwork journals, their narratives and the focus group discussion, along with quotes from the data to enhance the findings. Three main themes emerged from the study that tells the story of the students' experiences of using community entry skills in community fieldwork practice. These themes are: I) Challenges faced in community fieldwork practice, 2) Understanding Culture, and 3) Using Community Entry Skills.

Challenges faced in community fieldwork practice

The first challenge experienced in community fieldwork practice occurred before the students had even entered the fieldwork placement. Due to negative media commentary seen by the students about the community of Mitchells Plain, entry into their fieldwork placement occurred with preconceived notions about what the community was about. These pre-conceived notions then led to an experience of fear and anxiety about entering a community where drug and crime related incidents were rife, causing paranoia and apprehensiveness of what to expect in the community.

"I feel that because I listened to other peoples' comments about the community, read newspaper articles and watched the news about the community. I had painted a picture of the community in my mind and therefore by doing this I had judged not only the community but the community members. Most of the comments, newspaper articles and what I saw on the news about Mitchell's Plain community was so violent and gruesome that is literally made me scared to enter the community."

Being fearful and anxious about the community created a barrier between the students and the community, making the students feel unwelcome and causing them to experience the community and its people as "us and them". Being exposed to situations such as that of a young child looking after his younger sibling, while their parents sell fruit at a stall along the side of the road, or teenagers hanging around on street corners, left the students feeling frustrated and confused about the apathy they had witnessed in the community. Regardless of the feelings the students experienced by being exposed to these situations, it became evident that through spending time within the community, amongst the people, listening and looking at their way of life, is what allowed the students the opportunity to begin to learn more about the community. This in turn led to their realisation that it was their own preconceived notions that created the barrier between them and the community.

"At the same time by spending time in the community and with the members our fears about the community seemed to fade into the background. The more time we spent in the community we realised just how much our pre-conceived notions clouded our judgement."

Understanding Culture

Immersing themselves in the community the students visited the clinics, libraries and schools as well as the local shops, street vendors and were even invited into the homes of some community members. During these visits students would engage with the community members by having conversations with all three levels of Penina's Cup20 from the key role players to the silent majority. Interaction started off by showing an interest in who the community members are and engaging with them about their lived experiences and then evolved over time into establishing the needs of the community. However, even though they began to spend more time in and with the members of the community, the students still felt as if they did not understand some of the deeper issues of the community. Some of the things they questioned were why some of the community members were striving towards improving their lives while others seemed to be content with living the same lives their parents did. Or why some teenagers were content with dropping out of school and living on an unemployment grant while others strove to overcome the odds and gain a tertiary education. Understanding the history of a community is vital to understanding the essence of who the community is and how this history has impacted on the current state in the community.

"As we started working in the community we came to see how important it was to understand this history and understand how the history affects the people of the community at the present moment. As we started to discover this history we started to see the effect it has on the Mitchell's Plain community."

Immersing themselves in gaining an understanding of the apartheid history of the community of Mitchells Plain and the impact of the 1970's Group Areas Act19 on the lives of the community members forcibly removed from District Six, was a vital step in gaining an understanding of the community. Engaging in discussion about the history of the community however required them to look at how their own history and cultures played a role in how they viewed the community. This process required the students to gain an understanding of their own cultures and the impact that their culture had on who they are as people today in order to be able to understand the communities culture. Having an understanding of their own cultures allowed them to be able to separate their own cultures from that of the Mitchell's Plain community.

"As we came to discover, in order to understand the diversity that exists in the community we needed to first have an understanding of diversity amongst ourselves as a group before we could even begin to grasp the culture of the community."

In addition to understanding the history of the community the students realised that becoming a part of the community, by engaging with the community members in activities that are of importance to them, would further contribute towards gaining an understanding of the community and the culture of the community. Engaging with a community requires a mindfulness21 or awareness of one's intentions and actions when becoming immersed in the community. This process requires the culture of a community to be lived and experienced rather than observed from an outside perspective.

"Our aim was not to define culture as it cannot be defined but it was to gain an understanding and this can only be done once you become a part of the community. Becoming a part of the community was a conscious choice."

Using Community Entry Skills

The challenges experienced within community fieldwork practice ultimately led to the students understanding of the culture of the community but this process was achieved through the use of their community entry skills. The use of community entry skills allowed professionals to connect with the community and thereby gain an understanding of the community's culture.

"...I don't think there's any other way to actually... to gain that understanding, and to become part of the community and to make that transition from being an outsider to being part of it without using community entry skills"

The initial understanding and application of community entry was purely based on its three principles of look, listen and learn. The use of the first principle of look took place through observations of and interactions with the community, its environment, the services offered and the various policies that govern the community22 in order to try and establish a bigger picture of what the community was like. Linking the second principle of listen, to the first principle of look immersed the students amongst the community members where they could hear and see what the community was all about. This involved engaging in conversation with the community members on the streets and within various organisations.

"We had spent a great deal of time just listening to what the community members had to say. Spending time in the malls, in the clinics and even in the schools was, for us, ways of hearing the community's voice and which assisted us in learning more about the people of Mitchell's Plain."

The third principle of learn, is a combination of everything seen and heard in the community and from the community members. This principle is about finding the links between what has been seen and heard and analysing the dynamics between these interactions and allowing it to inform your understanding of the community. Even though these principles are listed and explained as separate concepts, the practical implementation of them requires a continuous, interactive use of all three principles simultaneously.

"You may look at something today and listen to something tomorrow, but it is the learning that is important. It is making the connection between what you see and hear and from gaining an understanding of the community."

The use of community entry is a skill that requires practice and needs to be developed and in order for it to be effective it needs to be used continuously when working with the community. Community entry is a tool that introduces professionals to the community, that allows professionals to interact with the community and its members, and that gives rise to the understanding that one receives while working within the community.

"For us it was as simple as walking through Town Centre, driving through the community and speaking to the community members themselves. As with any skill, community entry is something that needs practice, but does improve with time."

DISCUSSION

The aim of this research study was to learn from the experiences of five occupational therapy students working in the area of community development in order to inform occupational therapy education and practice. This research provides vital information related to this field, including a description of the challenges and opportunities that were experienced and a description of the students' reflective practice in order to develop and understand the importance of community entry as a vital aspect of community development.

Although Tareen and Omar5 propose five steps to community entry, it was felt that based on the students experiences, the process of community entry is a far more subjective experience such as that which Parasyn14 suggests. She encourages community developers on arrival and entry into the community to walk and not run through this process by experiencing the community first hand. This is in line with the experiences of the students in their use of community entry during fieldwork practice, whereas the use of the five steps to community entry as proposed by Tareen and Omar5 proved to be incongruous with the process of community entry in Mitchell's Plain.

The experience of the use of community entry skills show that in order to effectively engage with a community a conscious decision to become a part of the community has to be made. With the continued use of community entry skills as part of community development, community entry skills can be used as a tool that introduces the professional to the community, allows them to interact with the community and its members and gives rise to the understanding that one receives when working in a community.

There has been an increasing trend in a shift of occupational therapy services from traditional hospital/institutional based practice to include the social context which has created a need for occupational therapy programmes to ensure that students are well prepared to work within this expanding area of practice9. In learning from the students' experiences, this study is able to provide recommendations to knowledge and practice areas in occupational therapy education that need emphasis in order to support and assist future occupational therapists working in the field of community development.

The students' experiences of culture within the practice of community development indicates that there needs to be a greater emphasis on the importance of culture and cultural competence within occupational therapy training. This includes theoretical and practical skills as it is believed that the single most important factor in becoming culturally competent is exposure to culturally diverse situations23. Bennet's24 Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity is one example of a theoretical framework that can be used within undergraduate teaching which could assist students to understand the importance of culture and cultural development. This model emphasises that, with an increase in exposure to cultural difference comes an increase in cultural competence in intercultural relations.

It is essential that occupational therapy programmes prepare students to work in communities, to understand what communities are, how communities form and identify themselves, how they are governed, and especially how to identify resources and facilitate change in a community25. As identified through this study, an essential component of this process is the use of community entry skills that facilitated access into the community in order to have opportunities to gain an understanding of the community's culture.

In order for students to put their understanding of community entry skills into practice, occupational therapy programmes should provide students with the opportunity to engage with communities. Community based education, which the World Health Organisation (WHO)26 defines as a method of achieving educational relevance to community needs, could be used within occupational therapy programmes to offer services to the community as well as a means of educating students in socially responsive ways. Based on the students' experiences in community development, the study is therefore supported by Lauckner et al3when they state that in order to better understand the importance of community development, a practical component is essential in the preparation of occupational therapists.

CONCLUSION

This study is but a small step in dissecting all the various components of community development thereby providing guidance to occupational therapists in clarifying their role in the community. However, further research into the use of community entry skills and the importance of understanding culture as a part of community development is needed as a validation of this contribution to the field. As community development is an emerging field, future research in this area is encouraged as it will not only strengthen the role of the occupational therapist in community development and contribute to the preparation of students but also promote a greater awareness amongst not only fellow professionals but also the communities we serve regarding the valuable contribution that occupational therapy can make to the development of communities.

REFERENCES

1. McConnell C. Community learning and development: The making of an empowering profession. Community Learning Scotland, 2002. [ Links ]

2. Restall G, Leclair L, Banks S. Inclusiveness through community development. OT Now, 2005: 9 - 11. [ Links ]

3. Lauckner H, Pentland W, Paterson M. Exploring Canadian occupational therapists' understanding of and experiences in community development. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2007; 74(4): 314 - 325. [ Links ]

4. Wilcock A. An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated, 1998. [ Links ]

5. Tareen E, Omar M. Community entry: An essential component of participation. Health Manpower Management, 1997; 23(3): 97 - 99. [ Links ]

6. De Jongh J. An innovative curriculum change to enhance occupational therapy student practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2009; 39(1): 31 - 38. [ Links ]

7. Enothe. Community development and client participation approaches to addressing health inequalities. <www.enothe.eu/cop/cz_community_development.pdf>. (23 June 2011) [ Links ]

8. Labonte R. Community, community development and the forming of authentic partnerships: Some critical reflections, 2004. In Lauckner H, Krupa T, Paterson M. Conceptualizing community development: Occupational therapy practice at the intersection of health services and community. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2011; 78(4): 260 - 268. [ Links ]

9. Adams F, Wonnacott H. Group learning experiences in rural communities. In Lorenzo T, Duncan M, Buchanan H, Alsop A. (Eds.). Practice and service learning in occupational therapy: Enhancing potential in context. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2006. [ Links ]

10. Watson R. A population approach to transformation. In Watson R, Swartz L. (Eds.). Transformation through occupation (pp. 51 - 65). London: Whurr, 2004.

11. Lauckner H, Krupa T, Paterson M. Conceptualizing community development: Occupational therapy practice at the intersection of health services and community. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2011; 78(4): 260 - 268. [ Links ]

12. Swanepoel H, De Beer F. Community development: Breaking the cycle of poverty (5th Ed). Juta and Co Ltd, 2011. [ Links ]

13. Duncan M. Group processes in practice education. In Lorenzo T, Duncan M, Buchanan H, Alsop A. (Eds). Practice and service learning in occupational therapy: Enhancing potential in context. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2006. [ Links ]

14. Parasyn C. Aharenmen! Who better understands a community than those who live in it? <http://www.engagingcommunities2005.org/abstracts/Parasyn-Christina-final.pdf>. (16 April 2010). [ Links ]

15. Babbie E, Mouton J. The practice of social research, South African Edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

16. Goodley D, Lawthom R, Clough P Moore M. Researching life stories: Methods, theory and analyses in a biographical age. Cornwall: Routledge Falmer, 2004. [ Links ]

17. Denzin N, Lincoln Y The qualitative inquiry reader. London: Saga Publications, Inc, 2002. [ Links ]

18. Wall S. An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2006; 5(2): 146 -160. [ Links ]

19. The Group Areas Act. No.4I of 1950. http://www.historicalpapers.wits.ac.za/inventories/inv_pdfo/ADI 812/AD1812-Em3-1-2-011-jpeg.pdf (27 November 2014) [ Links ]

20. Croucamp A, Gasa N, Levendal E, Hutton B. Community Involvement and Participation. http://www.saavi.org.za/facmodule7.pdf (27 November 2014) [ Links ]

21. Cullen M. Mindfulness-Based Interventions: An Emerging Phenomenon. www.margaretcullen.com/docs/MBI-An_Emerging_Phenom-enon_Margaret_Cullen.pdf (28 November 2014) [ Links ]

22. Annett H, Rifkin S. (I995). Guidelines for rapid participatory appraisal to assess community health needs: A focus on health improvements for low-income urban and rural areas. Geneva, World Health Organization. (WHO/SHS/DHS/95.8). [ Links ]

23. Forwell S, Whiteford G, Dyck I. Cultural competence in New Zealand and Canada: Occupational therapy students' reflections on class and fieldwork curriculum. The Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2001; 68(2): 90-103. [ Links ]

24. Bennett M. Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In Paige M. (Ed). Education for the intercultural experience. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, 1993. [ Links ]

25. McColl M. What do we need to know to practice occupational therapy in the community? The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1997; 52(I): 11 - 18. [ Links ]

26. World Health Organization. Community based education of health personnel: A report of a WHO study group. World Health Organization Technical Report, Series 746, 1987. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nicola Vermeulen

Occupational Therapy Department

University of the Western Cape

Modderdam Road, Belville, Cape Town

nvermeulen@uwc.ac.za