Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.45 no.2 Pretoria ago. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/V45N2A4

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Developing a vocational rehabilitation report writing protocol - a collaborative action research process

Hester van BiljonI; Daleen CasteleijnII; Sanetta HJ du ToitIII

IB Occ Ther (UFS), M Occ Ther (UFS). Private practitioner at Work-link Vocational Rehabilitation practice, PhD candidate, Occupational Therapy Department, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Therapeutic Sciences,University of the Witwatersrand

IIB Occ Ther (Pret), B Occ Ther (Hons)(Medunsa), Dip Voc Rehab (Pret), DHETP (Pret), M Occ Ther (Pret), PhD (Pret). Associate Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Occupational Therapy Department, University of the Witwatersrand

IIIB Occ Ther (UFS), M Occ Ther (UFS), MSc Occ Ther (University of Exeter, UK), PhD (UFS). Affiliated lecturer, University of the Free State, Department of Occupational Therapy Lecturer, Discipline of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney

ABSTRACT

A vocational rehabilitation interest group of occupational therapists in the public healthcare sector of Gauteng, South Africa, identified the writing of reports as a practice problem. Supported by a PhD candidate, they developed a report writing protocol with report templates, using action research as methodology.

Collaborative steps, as part of an action research inquiry were taken to compile a concept report writing protocol and report templates. The concept protocol and templates were implemented in public healthcare vocational rehabilitation services. Critical reflection and feedback on the trial applications took place to refine the protocol. The protocol consisted of a cover letter, background information, legal and ethical considerations for reports, a step by step report writing guide including handy tips, report writing templates, and a guiding checklist. It concluded with a request for feedback from users, an undertaking for annual revision and suggested readings and skills training. Selected experts reviewed and critically appraised the final version. Dissemination of the final report writing protocol and templates was done through public healthcare forums and the annual vocational rehabilitation orientation workshop for occupational therapists entering public healthcare.

Key words: occupational therapy report writing, vocational rehabilitation, public healthcare, action research

INTRODUCTION

Professional report writing is a generic skill and its proficiency easily assumed. In vocational rehabilitation, report writing is an essential skill for occupational therapists as it directly implicates the outcome of the intervention1. Once the skill is mastered, the process of acquiring the experience and confidence for report writing is rarely systematically captured and skilled occupational therapy clinicians in public healthcare find it difficult to pass their skills onto less experienced and less confident colleagues.

In South Africa occupational therapy services in public healthcare are complicated by high staff turnover and a yearly influx of newly graduated community service occupational therapists who are often expected to render services and tasks they lack confidence and experience in. The general consensus from the Gauteng Vocational Rehabilitation Task Team (VRTT), an interest group of occupational therapists concerned with vocational rehabilitation services in public healthcare, was that experienced occupational therapists are usually in management positions and overloaded with managerial tasks, mentoring of new and inexperienced therapists, supervising students and carrying clinical patient care responsibilities. Members of the VRTT were also of the opinion that vocational rehabilitation report writing is an arduous task with potential conflict and repercussions as the report can be used by employees and employers for disputes and legal actions. As a result it appears that in some hospitals newly appointed and inexperienced occupational therapists refuse to write vocational rehabilitation reports, leaving it to their more experienced colleagues and therefore perpetuating the challenges and complications mentioned above.

The VRTT identified report writing as a priority practice problem to be addressed as a section of their bi-monthly meetings. The aim of this study was to develop an easily understandable, user friendly vocational rehabilitation report writing protocol with standardised report templates for the type of reports most commonly written in public healthcare. The reports identified to be most commonly written in Gauteng's public healthcare and for which templates were needed were: Functional capacity evaluation (FCE) reports; Policy and Procedure on Incapacity Leave and Ill-health Retirement for public service employee's (PILIR) reports; Disability Grant (DG) reports; Vocational Rehabilitation Screening Tool reports and medico-legal reports. The function of the report writing protocol would therefore be to: set a standard for vocational rehabilitation report writing; to standardise the format of a report; provide practical guidelines for inexperienced occupational therapists for writing vocational rehabilitation reports and thereby to enable therapists to spend less clinical time writing reports.

This article forms part of a PhD study, the purpose of which is to transform vocational rehabilitational services in Gauteng's public health care through action research. The article aims to describe the process and outcome of developing a report writing protocol and relevant templates using action research cycles to address a practitioner identified practice problem.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Scientific and grey literature were searched for articles with the key words; professional report writing, adult occupational therapy, protocol, vocational rehabilitation and public healthcare. The selected literature revealed that professional report writing skills, therapists' confidence and legal/ethical considerations were found to be recurring themes.

In vocational rehabilitation, the report forms the basis of decision making2. Preparing a useful and effectively written report is an important part of a therapist's work as it communicates future intervention or the results of intervention3,4. Buys identified knowledge, skills and values required by occupational therapists to deliver vocational rehabilitation services in South Africa. Among the important skills that Buys identified were report writing and competency in English as a business language. Beukes6 formulated a standard statement and measurement criteria for effective vocational assessment. She indicated that a report is compiled at the end of the assessment period and gives eight measurement criteria for report writing, for instance, recommendations regarding employability, a plan how to implement the recommendations made, and reports the assessment results to the referring agency. Her standard statement concludes that the report should focus on a worker profile of the client, and indicate problem areas and assets regarding the client's work abilities. De Clive-Lowe7 indicated that the ability to communicate the skills and techniques offered by the occupational therapist, are essential in a report, both for professional survival and for the long-term benefit of clients and emphasises that practice and training are needed to prepare well written reports.

The importance of accurate and skilled reporting of functional capacity evaluations are highlighted in several articles which also uses the ethical element of report writing1,3,8-14. Escorpizo et al 15 indicated that a successful vocational rehabilitation programme relies on the interrelationship between several elements and they note that effective communication between the employer and the healthcare practitioner is one such element. Reporting a client's work abilities accurately is essential in the rehabilitation process1,10,16. Buys and van Biljon1 noted that reporting the results of an occupational therapy functional capacity evaluation is often frustrating and time consuming, but without this vital step, the outcomes of the evaluation might not become a reality for the client. A framework for improving occupational therapists' opinions on work capacity17 indicated 17 guiding strategies and principles. Two of them are about report writing and advocate the practice of adopting a consistent occupational therapy assessment and reporting template and to shorten reports by reducing detail.

All newly qualified occupational therapists have to face the daunting transition from student to professional practitioner and the work environment and support they receive during this time have a significant impact on their confidence18. Developing and fostering professional confidence should be nurtured and valued to the same extent as professional competence, as the former underpins the latter, and both are linked to professional identity19,20. The teaching of structured writing, like report-writing, is important as a means of teaching therapists and students how to express and present information effectively, but also to facilitate scientific thinking21,22.

In South Africa there is legislation that impacts on the occupational therapist writing a vocational rehabilitation report. All occupational therapists should have a sound knowledge and understanding of the content and implication of such legislation and comply with these in practice.

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa23; the Bill of Rights (Chapter 2) affirms the democratic values of human dignity, equality and freedom. This holds implications for the content, the storage and the distribution of reports. The Promotion of Access to Information Act24 gives effect to the constitutional right of access to any information held by the State or any other person that is required for the exercise or protection of any rights and to provide for matters connected therewith. Informed consent, transparency and objective professionalism should permeate every aspect of the report and report writing practice.

Although report writing is not specifically mentioned in the following acts, reports can be seen as a form of communication with the client and this is addressed and outlined in the following legislation: The National Health Act25 provides a framework for a structured uniform health system within the Republic of South Africa, taking into account the obligations imposed by the Constitution and other laws in the national, provincial and local governments with regard to health services matters. The Health Professions Amendment Act26 led to the establishment of the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) and the latter provides control over the training, registration and practices of health care professions and matters incidental thereto. The HPCSA has ethical rules of conduct 27 that outlines the regulation of practice, including that of report writing, for all professionals registered with the HPCSA, including occupational therapy practitioners.

Occupational therapists need to be informed about legislation that has implications for injured and disabled workers that would affect the outcome of their vocational rehabilitation intervention. Their knowledge of this legislation should be reflected in the recommendations and suggestions made in the report for example; The Labour Relations Act28 which aims to promote economic development, social justice, labour peace and democracy in the workplace. The Employment Equity Act29 is concerned with promoting equal opportunity and fair treatment in employment through the elimination of unfair discrimination and implementing affirmative action measures to redress the disadvantages in employment experienced by designated groups. The Employment Equity Act ensures equitable representation of designated groups in all occupational categories and levels in the workforce. The Occupational Health and Safety Act30 provides for the health and safety of persons at work, in connection with plants and machinery and protection against hazards to health and safety arising out of activities at work.

Van der Reyden31 summarised the impact of legislation on occupational therapy practice in general and this understanding sets the tone for all report writing. She notes that acceptance of the client as an important partner in the healthcare process and acknowledgement of the individuals' ability to not only participate in, but make valid decisions about their lives, health, vocation/work and care is now central to every intervention. Such a mind-set diminishes the medical paternalism that formed the cornerstone of healthcare in the past. This mind-set should be reflected in the manner in which reports are written.

In the face of such challenges every effort should be made to mentor and support inexperienced occupational therapists to develop the relevant skills and confidence when writing vocational rehabilitation reports. Developing an easy-to-understand and user-friendly protocol with supportive templates and making sure that all therapists entering public healthcare are acquainted with it was directed at meeting the above challenge.

METHOD

Study design

The epistemology of action research permeated this study. Action research facilitated a process for protocol and report format development while simultaneously transforming practice. This process relied on a collaborative effort between the practitioners and the researcher adhering to an action research approach of working towards practical outcomes while contributing towards human emancipation and transformation32. It allows practitioners to be fellow researchers and participants, learning from experiences and producing knowledge that is relevant to their practice situations and to which they can relate33.

Population

In this study the researcher (first author) as an outsider was invited to collaborate with a group of insiders as they shared the common goal of developing a report writing protocol and templates for the vocational rehabilitation services in Gauteng public healthcare. These insiders are described by Dick34 as stakeholders - persons involved who have a stake in a programme and who are affected by or able to effect practical change. In this research the VRTT of Gauteng constitutes the stakeholders. The VRTT is a group of occupational therapists with an interest in vocational rehabilitation, working at four large academic hospitals in Gauteng's public healthcare sector in which vocational rehabilitation services are offered. The group was formed in 2011, by the Assistant Deputy Director of Gauteng Health, to resuscitate and support occupational therapy's vocational rehabilitation services in Gauteng public healthcare.

The structure for participation that guided the action research process was created when the researcher (first author) was allowed entry into the VRTT as an honorary member. Her PhD, titled 'Transforming Vocational Rehabilitation in Occupational Therapy Departments in Gauteng public healthcare through Action Research' corroborated the VRTT vision.

A selected group of experts in vocational rehabilitation was incorporated as 'critical friends'35,36 for their critical reflection, opinion and comment of the final protocol and templates for report writing. The selection criteria for inclusion into this group were occupational therapists with previous or current experience of working in South Africa's public healthcare and current experience of more than 5 years of working in and/or teaching vocational rehabilitation. Twelve such stakeholders were identified and 7 responded within the requested time frame.

All participants were informed verbally and by a written pamphlet that they could keep, that this project was part of a larger PhD study. How this project fitted into the study and how the generated knowledge would be used was discussed and consent forms were signed.

Data collection

After the VRTT members identified the practice problem of vocational rehabilitation report writing the researcher suggested addressing the problem through action research cycles35. Care was taken to process all decision making through the VRTT to avoid power relationships that could jeopardise the emancipatory nature of action research37. Data were captured in the form of the VRTT meeting minutes. The researcher trained the participants in reflective journaling. They applied this technique and reflected after each meeting. The researcher kept her own reflective journal. While participants were using the report writing templates, they communicated through an e-mail group to clarify and discuss practice issues. Participants were encouraged to keep field notes to capture their experience and these were shared during the VRTT meetings as verbal feedback and/or written notes.

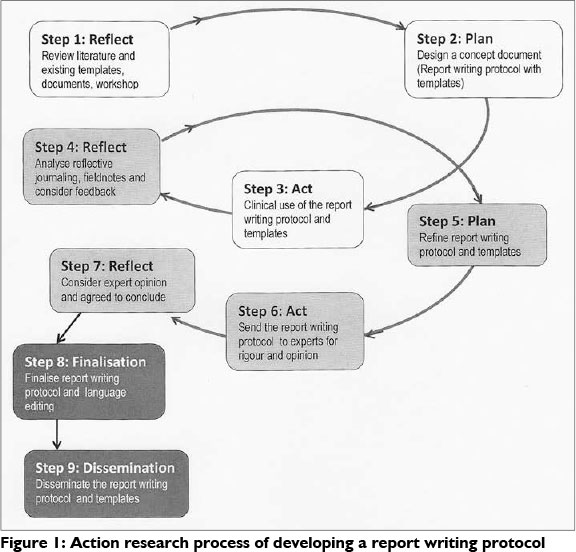

The report writing protocol and relevant templates were researched in the cyclical action research process of reflect-plan-act33. Nine steps ensued. Figure I is a graphical representation of these nine steps, encapsulating the natural progression of the reflect-plan-act process that evolved during the research process.

In step one (Figure I) the researcher enabled informed reflection on report writing for vocational rehabilitation services as she presented the results of a literature review in the form of a workshop to the VRTT. This workshop focused on report writing for vocational rehabilitation in public healthcare.

A variety of report writing templates were studied and discussed and five service specific templates were compiled for FCE, PILIR, DG, vocational rehabilitation screening tool and medico-legal reports. A draft report writing protocol with templates was planned and drawn up in step two. The decision was made to test these in the respective vocational rehabilitation practices, keep field notes and report back at the next VRTT meeting. This step focussed on the attainment of action-orientated outcomes and supported the validity of the research process38.

This draft protocol and templates were put into action and used for two months in vocational rehabilitation practices at public healthcare hospitals as step three. The VRTT members and their colleagues who offered vocational rehabilitation services participated in this action phase. Process validity was promoted due to the active generation of new knowledge by all stakeholders during this step38.

The VRTT members brought their findings and experiences back to the group in the form of verbal feedback and field notes. Analysis and critical reflection of the experiences and feedback was considered and discussed in step four. Therefore, the promotion of democratic validity was an inherent part of the process38.

Step five's planning took cognisance of the feedback, field notes, reflections and refinement of the report protocol and templates. This was done by the researcher and presented for verification and approval by all participants at the following VRTT meeting.

The action to validate and enrich the credibility of the report writing protocol and templates was in step six. The report writing protocol was sent for objective and critical appraisal to pre-selected vocational rehabilitation experts who responded in electronic format with their opinions and comments.

Their opinions were considered, reflected on and incorporated in step seven.

In step eight the report writing protocol tool and templates were finalised. These were sent for language editing and compiled into an easy to use, bound hard copy document and in electronic format.

The dissemination of the finalised protocol and templates comprised step nine. The electronic format of the report writing protocol and templates were shared with all occupational therapists doing vocational rehabilitation in Gauteng public healthcare through official public healthcare forums. It was included as a training session in the annual vocational rehabilitation orientation workshop for occupational therapists entering the public healthcare for the first time. They were given a paper copy with the option to request electronic copies from one of the members of the VRTT (the secretary). The process of developing the report writing protocol will be more widely disseminated through this article in the South African Journal of Occupational Therapy.

Data Analysis

The field notes, reflective journaling and meeting minutes were systematically analysed by the researcher through thematic and discourse analysis. In keeping with good practice, thematic analysis and in support of action research principles35,39 the raw data were manually checked and analysed immediately after gathering, throughout the process. Data were summarised and categorised. These summaries drove and dictated the next action research phase. For the results and discussion thereof in this article, data used in the phases are indicated as M for meeting minutes, F for field notes and R for reflective journaling.

The results and discussion are integrated to ensure a thick description and to provide literature and investigators (both stakeholder and researcher) the triangulation of findings.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

1. Action cycle

The focus of the embedded action cycle was to address a lack of professional standards in vocational rehabilitation reports within public health care. The involvement of VRTT members ensured that novice and expert practitioners contributed to a report writing protocol that would be accessible to all occupational therapy practitioners. Attention was given to:

- Language proficiency: The finalised report writing protocol for vocational rehabilitation services in public healthcare is written in easy to understand English. A language editor was an unplanned but valuable addition. This person added practical suggestions and generic principles on report writing e.g. 'use polite language' and 'think before you type it out'.

- Design: It consisted of a cover letter, background and general information, legal and ethical considerations, a report writing process, templates, report writing tips, a checklist, conclusion and references (with recommended reading and skills training). The cover letter was personalised with an informal tone to introduce the tool. The authors, contact details and the date of the document were included. Legal and ethical considerations specifically referred to challenges experienced in public health. Practical guidelines included how many pages the different types of reports generally were and an estimated time an experienced therapist would take to write such a report.

- Methodical instructions: The report writing process was described systematically in 12 practical step-by-step instructions. A check list that therapists should check before and after writing a report was included. Table I presents the checklist.

- Conformity: To ensure a degree of uniformity report templates were drawn up for FCE reports, PILIR reports, DG reports, vocational rehabilitation screening tool reports and medico-legal reports.

Using scientific literature is a well-known and respected practice when developing a protocol40,41. There are, however, several reasons why this practice was not sufficient evidence to draw up a protocol for occupational therapists' report writing of vocational rehabilitation services in the context of public healthcare in South Africa.

The first reason is that there are limited literature, guidelines and/or written instructions available on occupational therapy report writing for vocational rehabilitation in South Africa. What there was, are mostly used within universities and drawn up for the purpose of teaching undergraduate occupational therapy students.

Secondly, the practical nature of report writing lends itself to be investigated through methodologies such as action research. This methodology allowed for the active participation and involvement of practitioners in addressing their own practice problems and developing appropriate solutions. This was affirmed in this study when concerned occupational therapists developed a vocational rehabilitation report writing protocol, using action research to complement a literature review.

A third reason was that public healthcare is a unique working milieu with opportunities and challenges that are not formally documented and best known to practitioners working within the context. This was constantly taken into consideration with the development of the report writing protocol.

2. Research cycle

The focus of the embedded research cycle was to generate new knowledge relating to setting professional standards for report writing protocols when working in collaboration with practitioners. The generation of new knowledge was a collaborative effort between vocational rehabilitation practitioners as insiders within the Gauteng public health service and the researcher as an outsider. The action research process promoted different modes of participation and resulted in evolvement of relationships and associated actions of the parties involved.

Evolvement of the insider perspective: The initial co-option of the VRTT members meant they were chosen as mere representatives of the interest group but through their collaboration as stakeholders they could have felt that they had real power.

The VRTT had three meetings in which the need for standardisation of vocational rehabilitation report templates and the report writing process was noted. Meeting minutes (Ml, 2, 3) showed discussions related to problems of report writing i.e. the need to write better reports, therapists feeling they should spend less time writing and reading reports as it kept them away from client contact and concerns about the quality of vocational rehabilitation reports going out from public healthcare services.

After six months these identified problems had not been addressed and the researcher offered to present a workshop on current report writing literature, legislation and ethical issues relevant to report writing. Although requested to collaborate by bringing existing documentation, none of the participants brought templates or prepared for the meeting and a concept protocol could not be drawn up. However, a discussion on the different types of reports that were being written and the practice of report writing ensued. This discussion ensured that the stakeholders felt consulted and provided input. They realised the scope of their role as stakeholders.

Evolvement of outsider perspective: The researcher as an outsider and well-established private practitioner in the field of vocational rehabilitation was initially challenged by the potential power relations between her and the rest of the VRTT members. Her defined roles as catalyst and informed observer33 were initially undermined due to that fact that she was also acting as data collector and offered to act as mentor throughout the process. The latter could both be interpreted by VRTT members as authoritative roles. However, active involvement in the action research process allowed the researcher as an outsider to facilitate collaboration with insider members that was more reciprocal in nature38.

The researcher shared and exposed her expertise during the workshop covering current report writing literature, legislation and ethical issues relevant to report writing. She promoted a situation for co-learning and facilitated an agreement between all parties to work on a joint aim: drawing up templates and a protocol that would enable therapists to spend less time writing reports, set a vocational rehabilitation report standard and give practical guidelines for new/ inexperienced occupational therapists to use. Her willingness to support collective action ensured that the practice problem was addressed. Electronic copies of report templates and suggestions for the protocol were emailed to her so that she could initiate a concept protocol and template for each of the types of report discussed. Five of the seven therapists complied with the provision of information (M6). Cooperative engagement was documented at a follow-up meeting when a VRTT member expressed:

"I am glad we can share this (a report writing protocol and templates) with therapists in secondary and primary healthcare facilities as they will also benefit from it." (R3)

At the same time reflective journaling by VRTT members showed a positive disposition towards the process. The feeling was that it was a worthwhile exercise for the group to engage in, especially as it would hold benefit for new and inexperienced therapists.

Reciprocal collaboration: Stakeholders were encouraged by the achievement of the action-orientated outcomes and collaborated in discussing and brain storming options for the draft protocol. Representatives from each hospital were given a file with the draft protocol and electronic report templates were e-mailed. All members agreed to trial the protocol and associated templates. The researcher maintained her facilitative role and sent out two emails and one text message as a reminder to the members of the VRTT to use the templates and protocol and prepare for the feedback. These messages were accompanied by an offer to assist if there were difficulties.

Co-learning continued during the feedback session after the initial report writing protocol tool was implemented (see Table II). The suggestions and feedback by VRTT members were analysed and incorporated in refining and improving the report writing protocol as well as the templates and represented for verification at the following VRTT Meeting (M7). Progress towards the agreed aim empowered VRTT members to the extent that one observed:

"It feels as if we are moving forward despite our current challenges (practising in public health care)" (R5).

The extent of true ownership is most evident in how the VRTT agreed to disseminate the final protocol and templates. Reflective journaling after this discussion showed that:

"The plan to publish what we have achieved as a team excites me. I feel it is important to share our knowledge and skill with our peers and those therapists with little or no experience in vocational rehabilitation" (R6).

To ensure ownership and as respect to the generation of new knowledge the end of the document stated that the protocol is the intellectual property of the VRTT, Gauteng Health and should be acknowledged as such.

During the development of an audit tool for allied healthcare professionals in Gauteng's public healthcare, Foote et al42 noted that quality improvement is a dynamic process and needs to be incorporated on a broader basis with service improvement within the Department of Health. They advocate that service improvement should be in line with the South African governments 'Batho Pele' (People First) initiative for quality and accountability in the public healthcare sector"42. Robinson and Botha43, in an article on quality management in occupational therapy recommend that increased standardisation for documentation, and its auditing, should be promoted and advocated. The development of a report writing protocol and templates echoes these sentiments and hoped to encourage similar activities to improve occupational therapy's services to their clients in public healthcare.

The occupational therapists rendering the vocational rehabilitation services actively participated in generating the knowledge and practical solutions sought to address their report writing problem. In the process they also experienced ownership of the outcome34,35,37.

The effectiveness of a protocol lies in the hands of the clinicians for whom it was written. The accessibility of a protocol lies in the hands of the authors who drew it up. A number of suggestions for protocols to have a sustaining impact flowed from this research and are given below.

Practice problems are often addressed by policy makers isolated from the realities of everyday clinical practice. The authors of a protocol and clinicians to whom it applies need to work together to ensure that the content of protocols are relevant to the contexts they apply to. Action research is suggested as a methodology to drive the development of protocols as it ensures its authenticity39. The data captured to form the content of the protocol will then be relevant and meaningful to health practitioners who will be using it. Action research frames the solution to a problem within the context it is to be used in44.

3. Anticipated future action cycles

Awareness and understanding of this newly developed protocol would be essential. It could be introduced and taught to all occupational therapy practitioners entering a vocational rehabilitation service during orientation periods. Regular in-house workshops need to be done to refresh the commitment and memory of experienced therapist who might have become trail-weary.

Clinical managers could find it a long term benefit to sporadically monitor the practical application of protocol content and when necessary mentor the implementation and application.

Where occupational therapists lack confidence and experience it needs to be addressed within the practice and by the institutions where they are employed. Holland et al19. describe professional confidence as a dynamic, maturing personal belief held by a professional or student. This includes an understanding of and a belief in the role, scope of practice, and significance of the profession. It is based on their capacity to competently fulfil these expectations, fostered through a process of affirming experiences. Having protocols is one way to enable this20. Mentoring could also be considered to facilitate the transformation.

Finally a protocol needs to be regularly revised to ensure continuous evolvement to keep up with ever-changing healthcare environments as well as client and practitioner needs. This can only be done if there is feedback from the practitioners using it.

CONCLUSIONS

The action research design applied in this study suggested that a combination of scientific information and practical experience resulted in a trustworthy report writing protocol for the solution of an occupational therapy practice problem. This reciprocal collaboration is one of the inherent characteristics of action research. The VRTT and the researcher endeavoured to continue to use action research in future vocational rehabilitation practice transformation in Gauteng's public healthcare.

The authors would like to caution that a relevant and well researched report writing protocol does not in itself guarantee good practice. It should be accompanied and supported with mentoring, effective management, regular training and updating of practitioners' skills. Once these are entrenched in practice, occupational therapists can say with conviction that their client's best interests are being place first: Batho Pele.

The Report Writing Protocol has information on the latest legal and ethical consideration related to writing a report, a step by step writing guideline, report templates, ergonomic considerations for a computer workstation, some 'golden rules and tips' from experienced report writers and checklists to use before and after writing a report. An updated protocol is available to any interested person from Naazneen Ebrahahim who is the designated Report Protocol VRTT member. Her contact detail is nazneen.ebrahim@gmail.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Stakeholders and members of the VRTT: Simon Rabothata, Sadjida Khamker, Ashley Magner, Naazneen Ebrahim, Claudette Parkinson, Mashudu Mphohoni, Catherine Couvaras, Buhle Mkhizi, Lynn Soulsby

The experts who responded and contributed towards the finali-sation of the protocol: Lee Randall, Rene Walker, Megan Spavins, Janine Schoeman. Derryn Brummer, Megan Townshend, Jane Baker.

The 2013 Faculty of Health Sciences Development Grant from the University of the Witwatersrand.

REFERENCES

1. Buys TL, van Biljon HM. Functional capacity evaluation: An essential component of South African occupational therapy work practice services. Work, 2007; 29: 31-6. [ Links ]

2. Chamberlain MA, Moser VF Ekholm KS, O'Conner RJ, Herceg M, Ekholm J. Vocational Rehabilitation: An Educational Review. Journal Rehabilitation Medicine, 2009; 41: 856-69. [ Links ]

3. Coole C, Birks E, Watson PJ, Drummond A. Communicating with Employers: Experiences of Occupational Therapists Treating People with Musculoskeletal Conditions. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2013; Springer. [ Links ]

4. Ownby R, Brandon V Psychological reports: A guide to report writing in professional psychology. US: Clinical Psychology Publishing Co, 1987. [ Links ]

5. Buys TL. Professional competencies required by occupational therapists delivering work practice services to workers with disabilities in the South African open labour market. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2006. [ Links ]

6. Beukes S. The accreditation of vocational assessment areas: Proposed standard statement and measurement criteria. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2011; 41(3): 42-9. [ Links ]

7. de Clive-Lowe S. Outcome Measurement, Cost-Effectiveness and Clinical Audit: the Importance of Standardized Assessment to Occupational Therapists in Meeting these New Demands. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1996; 59(8): 357-62. [ Links ]

8. Mitchell T. Utilization of the functional capacity evaluation in vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 2008; 28: 21-8. [ Links ]

9. van Biljon HM. Occupational Therapists in Medico-Legal Work -South African Experiences and Opinions. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2013; 43(2): 27-33. [ Links ]

10. Vinciguerra E. Work Capacity Evaluation for Disability Grant Purposes: Introducing an Evaluation Tool for Occupational Therapists. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 34(3): 14-7. [ Links ]

11. Innes E, Straker L. Attributes of excellence in work-related assessments. Work, 2003; 20: 63-76. [ Links ]

12. Brink KS. Applying the use of activity in the assessment of malingering: A case illustration. Work, 2001; 29: 47-53. [ Links ]

13. Jansen van Vuuren M. Occupational Therapy Assessment and the Medico-Legal Report: The Legal Perspective. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State; November 2012. [ Links ]

14. McCluskey A, Lukersmith S. A proposed curriculum and strategies for improving occupational therapists' report writing, court performance and expert opinion on work capacity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2008; 55(2): 144-5. [ Links ]

15. Escorpizo R, Ekholm J, Gmünder H, Cieza A, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G. Developing a Core Set to Describe Functioning in Vocational Rehabilitation Using The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2010; 20(4): 502-11. [ Links ]

16. Jackson M, Harkess J, Ellis J. Reporting Patients' Work Abilities: How the use of Standardised Work Assessments Improved Clinical Practice in Fife. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 67(3): 129-32. [ Links ]

17. Allen S, Carelson G, Ownsworth T, Strong J. A Framework for Systematically Improving Occupational Therapy Expert Opinions on Work Capacity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2006; 53: 293-301. [ Links ]

18. Adam K, Strong J, Chipchase L. Foundations for work-related practice: Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy entry level curricula. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 2013; 20(2): 91-100. [ Links ]

19. Holland K, Middleton L, Uys L. Professional Confidence: A Concept Analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2012; 19(2): 214-24. [ Links ]

20. Gray M, Clark M, Penman M, Smith J, Bell J, Thomas Y et al. New Graduate Occupational Therapists Feelings of Preparedness for Practice in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2012; 59(6): 445-55. [ Links ]

21. Marshall S. A Genre-based Approach to the Teaching of Report-writing. English for Specific Purposes, 1991; 10(1): 3-13. [ Links ]

22. Lichtenberger E, Mather N, Kaufman N, Kaufman A. Essentials of Assessment Report Writing Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL, editors. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2004. [ Links ]

23. Republic of South Africa. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996, (1996). [ Links ]

24. Republic of South Africa. Access to Information Act 2 of 2000., 2 (2000). [ Links ]

25. Republic of South Africa. National Health Act No. 61 of 2003 No. 26595 (2003). [ Links ]

26. Republic of South Africa. Health Professions Amendment Act 29 of 2007, 30674 (2007). [ Links ]

27. HPCSA. Ethical Rules of Conduct for Practitioners Registered under the Health Professions Act, Health Professions Act 56 of 1974 (2006). [ Links ]

28. Republic of South Africa. Labour Relations Act (No 66 of 1995), (1995). [ Links ]

29. Republic of South Africa. Employment Equity Act, 1998 (No 55 of 1998) Code of good practice., (1998). [ Links ]

30. Republic of South Africa. Occupational Health and Safety Act, 1993 (No 85 of 1993), 25129 (1993). [ Links ]

31. van der Reyden D. Legislation for Everyday Occupational Therapy Practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2010; 40(3): 27-35. [ Links ]

32. Reason PAB. Handbook of Action Research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2007. [ Links ]

33. Zuber-Skerritt O. Action Learning and Action Research. Songlines through Interviews. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers, 2009. [ Links ]

34. Dick B. Entry and Contracting. Action research and evaluation on-line. Australia: www.aral.com.au/areol; 2013. [ Links ]

35. McNiff J. Concise Advice for New and Experienced Action Researchers. Action Research for Professional Development. Dorset: September Books; 2010. [ Links ]

36. Costa A, Kallick B. Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 1993; 51(2): 49-51. [ Links ]

37. du Toit S, Wilkinson A. Research and Reflection: Potential Impact on the Professional Development of Undergraduate Occupational Therapy Students. Springer Science + Business Media, 2010; 23(Systematic Practical Action Research): 387-404. Epub 5 February 2010. [ Links ]

38. Herr K, Anderson GL. The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty. United States of America: SAGE, 2005. [ Links ]

39. Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design (2nd ed). CA Sage: Thousand Oaks, 2007. [ Links ]

40. Joanna Briggs Institute. Train the Trainer Program. Wits- JBI Affiliate Center for EBP: 2013. [ Links ]

41. Tanner-Smith E, Wilson SJ. Systematic Reviewing for Evidence-Based Practice: An Introductory Workshop.The Campbell Collaboration, editor. University of the Witwatersrand Graduate School of Public and Development Management: Peabody Research Institute, Vanderbilt University; 2013. [ Links ]

42. Foote H, Lamont S, Burger E, Leishman A. The Introduction of a Quality Assurance Programme in Gauteng Health Hospital Occupational Therapy Services. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2006; 36(1): 6-10. [ Links ]

43. Robinson H, Botha A. Quality Management in Occupational Therapy. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2013; 43(3): 8-18. [ Links ]

44. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research 2nd Edition. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2009. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Hester van Biljon

PO Box 830

Auckland Park, 2006 Johannesburg

vanbiljon@mjvn.co.za