Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.45 n.1 Pretoria Jan./Apr. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45no1a10

SECTION 1

Course redesign to promote local and global experiential learning about human occupation: Description and evaluation of a pilot effort

Rebecca M. Aldrich

B.S. OT (University of Southern California), M.A. OT (University of Southern California), Ph.D. in Occupational Science, (University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill) Assistant Professor, Saint Louis University

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Globalisation heightens the need for diverse learning experiences regarding human occupation. This article describes a two-phase redesign of an undergraduate occupational science course that generated community outings in the United States (U.S.) and synchronous online interactions between U.S. and Swedish students. Via experiential learning opportunities, the course redesign aimed to enhance students' understanding of occupational science and occupational therapy concepts as well as how such concepts are taken up across global contexts.

METHOD: 96 undergraduate U.S. occupational science students participated in community outings, and 52 of those students also participated in synchronous online interactions with 35 undergraduate Swedish occupational therapy student peers. U.S. students provided feedback about the community outings and synchronous online interactions via written course evaluations and reflections.

RESULTS: U.S. students perceived community outings and synchronous online interactions as positive learning opportunities but also suggested possible improvements which have been implemented in subsequent iterations of the course.

CONCLUSIONS: When accompanied by structured reflective opportunities, local and global experiential learning can positively impact students. It is important to consider how experiential learning fits within course objectives, as well as how technology enables or inhibits experiential learning across local and global contexts.

Key words: Experiential learning, learning spaces, synchronous online education, occupational science, occupational therapy

INTRODUCTION

We are living in a global era: people and ideas are flowing more easily across international boundaries than ever before1. Thanks to globalisation and technology, many people can encounter foreign events and viewpoints on a daily basis. This facet of contemporary life commands people's ability to acknowledge and account for a diversity of perspectives and practices. Such a demand is especially salient for occupational therapists, whose work increasingly entails interacting with clients and colleagues from varied backgrounds. For over a decade, occupational therapists have discussed the need for globally-relevant practice, but related conversations about globalising occupational therapy education2-3 have not been as thorough or sustained. Current university and health care priorities reinforce the need for international experiences in occupational therapy education4. The global growth of occupational science5 suggests that concepts related to human occupation can provide a foundation for occupational therapists around the world. Therefore, occupational science and occupational therapy educators have a timely opportunity to explore how concepts related to human occupation can be combined with international learning experiences.

This article describes the two-year process of redesigning an undergraduate occupational science course to meet the needs expressed above. As will be explained, the redesigned course is part of an undergraduate occupational science degree that precedes a graduate occupational therapy degree. The course redesign culminated in synchronous (or real-time) online interactions between occupational science and occupational therapy students in the global North; however, it began with a focus on enhancing local experiential education for occupational science students in the United States (U.S.). By outlining the process of course redesign as well as students' perceptions of redesigned course elements, I hope to stimulate three interrelated conversations: one about the importance of experiential learning in occupational science and occupational therapy education, one about the value of occupational science education as a foundation for experiential learning, and one about the conceptual and logistical aspects of designing experiential learning opportunities.

The next section of this article weaves a broad description of the course with the rationales for redesigning it, situating experiential learning opportunities within particular views of student educational needs. The methods section will describe how students provided feedback about redesigned course elements, and the results section will summarise students' comments about learning via redesigned course elements. The article will conclude with factors for educators to consider regarding experiential learning about human occupation.

COURSE DESCRIPTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Background

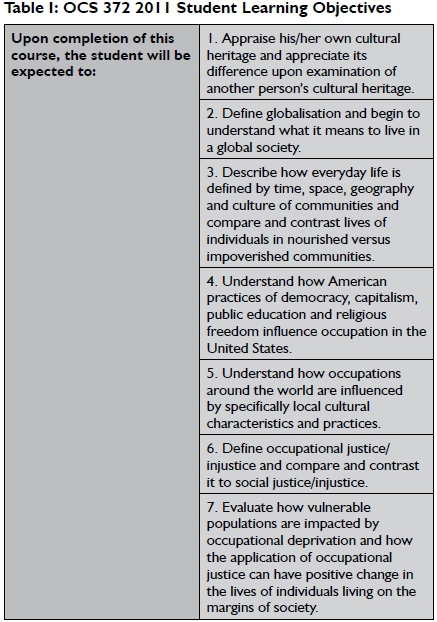

This course redesign occurred at a private urban university that serves approximately 13,000 students in the Midwestern region of the U.S. The university offers two degree programmes related to human occupation: a Bachelor of Science in Occupational Science (BSOS) and a Master of Occupational Therapy (MOT). Approximately 75% of the students in the MOT programme also complete the BSOS degree at the university; thus, the seven occupational science courses in the BSOS program form a foundation for those students' MOT education. In January 2012, I began teaching one of three courses that comprise the final semester of the BSOS programme. The course - OCS 372 - had been designed prior to my arrival at the university as a traditional three-hour lecture/ discussion that also required 24 hours of community-based service learning. Per the learning objectives listed in Table 1, OCS 372 addressed culture, marginalisation, and the importance of understanding "others" in U.S. health care practices. [See Table 1 on page 57]. As an occupational science course, OCS 372 did not teach practice-related skills, but it did link to occupational therapy by emphasising cultural competency, occupational justice, and the notion of therapeutic relationships.

When I assumed primary teaching responsibility for OCS 372, I consulted with the previous OCS 372 instructor as well as the department chair to minimally modify the course. I updated course content relative to occupational justice6 and the political practice of occupational therapy7, and I reframed OCS 372 as an exploration of the diverse city in which the university is located. My views as a teacher and scholar set a larger course redesign in motion based on those two initial modifications. As a teacher and community-engaged researcher8 who believes that knowledge must be "... adequate to experience"9, I aim to connect course content to students' realities and make knowledge useful in everyday life. I also recognise, as Thi-beault argued, that universities often "... train tomorrow's decision makers with yesterday's obsolete paradigms. And we train them in a vacuum: the vacuum of the rich"2:160. The risk of keeping students in 'the vacuum of the rich' was palpable when I took over OCS 372: most students at the university existed in a campus 'bubble' that was separate from the surrounding urban community. Although OCS 372's service learning component connected students to a community site, I believed that students would better understand ideas like occupational justice and the political practice of occupational therapy if they could apply them with a variety of local places and people. Thus, I wanted to get OCS 372 students further out of traditional classrooms to experience their learning across their city of residence. I also wanted students to understand how the topics they explored locally - such as poverty and immigration - aligned with global emphases on political and transformative occupational therapy6,7. By initiating a course redesign based on these aims, I intended to help counteract the trend of occupational therapy students "going through their whole university training without being exposed to the global issues that will shape their future"2:160.

The first phase of the OCS 372 course redesign began in 2012 and focused on enhancing opportunities for local experiential learning. The second phase, which was initiated in 2012 but did not take effect until 2013, focused on creating opportunities for international interactions that would augment students' understanding of course concepts.

Redesign #1: Experiential learning via community outings

To refocus OCS 372 on the university's local context, I explored new options for experiential education. Helen Jeffrey wrote that experiential education fosters "...the development of critical thinking skills through immersion in real life problems, application of knowledge in complicated and ambiguous situations and a deeper level of understanding of content than is possible from classroom teaching"10:6. In exploring different ways to immerse students in their community, my role as an educator shifted toward "...cultivat[ing] an environment to establish the physical and social context for learning"10:7. The Deweyan orientation of such a role fit with the foundation and current direction of occupational therapy education11-13 as well as my personal teaching philosophy. Existing literature also indicated that experiential learning had been positively utilised in occupational therapy education13, so it seemed that experiential learning might similarly serve occupational science education.

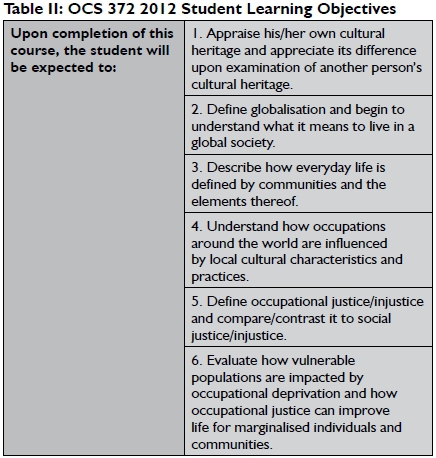

With these ideas in mind, I designed and implemented two experiential community outings when I took over OCS 372 in 2012. I scheduled the outings during the last half of the course so students could develop conceptual understandings prior to applying their knowledge to community examples. I restricted the number and duration of the outings based on the logistics of scheduling outings and organising outing transportation. In selecting two outing destinations - a family-focused community development organisation in the north part of the city and a religious community center in the south part of the city- I aimed to move students into spaces that would foster different considerations of courserelated questions and concepts. Located within a 10-mile radius of each other, the outing sites also introduced students to particular minority groups, African-Americans and Bosnians, that constituted the city's social fabric. Although many OCS 372 students hailed from the region surrounding the university, most of the students had never ventured outside the campus "bubble" to the neighborhoods in which the outings were located. Likewise, whereas most OCS 372 students had some knowledge of various ethnic groups in the city, many students did not have substantive contact with members of those groups prior to the course. The outings thus promised to provide students with greater knowledge about their city as well as experiential learning relative to the first, third, and sixth OCS 372 student learning objectives (see Table 2).

As a framing for the outings, I told the students that the university's classrooms were only one type of learning space and that, on two occasions, the community "classroom" would take the place of an on-campus session. I further framed the outings as showcasing well-known diverse communities and helping students think about how they might serve such communities as occupational therapists. During the outings, students listened to a community speaker discuss the site's activities, the population the site served, and aspects of everyday life in nearby communities. Following each speaker's presentation, students had open time for questions until the hour-long visit ended. In line with the university's Ignatian pedagogical underpinnings14, I asked each student to write a 3-4 paragraph online reflection in the week following each outing. The reflection addressed how the outing influenced the student's views of the city; the student's perspective on the link between culture, occupation, and marginalisation; and any lingering questions that the outing stimulated. The on-campus class session following each outing involved an instructor-led debriefing as well as collective discussions based on students' individual written reflections.

Redesign #2: Incorporate global perspectives via synchronous international online interactions

As I incorporated community outings into OCS 372, I continued to believe that the course lacked an essential connection to global perspectives. The BSOS programme gave no leeway or financial support for international travel during OCS 372, so I tapped a formal university mechanism to facilitate global interactions in the course. Full-time faculty members at the university who wish to design or redesign a course may apply for a competitively-awarded Innovative Teaching Fellowship that includes a course release, support from an instructional designer, and an opportunity to teach in the campus' technology-rich Learning Studio. I received the Fellowship in March 2012 and began the second phase of my course redesign in the subsequent summer. The limited occupational therapy scholarship on teaching and learning15-17 offered little guidance for this aspect of the course redesign, but it did suggest that new instructional designs18 related to online technologies13,19 and synchronous student collaborations20 showed promise, especially when coupled with structured reflection20. (More recent examples of technology-based international occupational therapy educational collaborations21 were not published when I undertook the course redesign.) After reviewing existing literature, I worked with a campus instructional designer through the end of 2012 to investigate how the Learning Studio could support international interactions in OCS 372.

The Learning Studio was designed by a team of faculty members, instructional design staff, and students with the goal of creating an experimental space that promotes discovery-based learning. The Learning Studio contains moveable group tables and wheeled office chairs; wall-mounted and mobile whiteboards; two classroom-level video cameras with ceiling microphones and integrated speakers; a multi-input video wall; and a variety of tablets and laptop computers that can be linked to the video wall through a wireless remote projection system (see Image 1).

Learning spaces like the Learning Studio can promote active teaching and learning that is more enjoyable than what occurs in a traditional lecture-oriented classroom22 where the "... ex cathedra layout of a lecturer at the front with ranks of students laid out before her or him"23:234 can stifle discussion and interaction. However, traditional classrooms dominate occupational science and occupational therapy education because "it remains the case that a room, with tables and chairs, and a means of displaying information for all tosee, remains the basic non-specialist teaching space in higher education"23:234. I wanted to maximise the Learning Studio's potential for encouraging deep learning and active engagement24, and through my course release and work with the instructional designer, I learned that "... it is not the delivery method that is the key feature, but rather the design of the instruction and what students bring to the learning situation"19:73 that is important to build upon.

In addition to their own life experiences, students brought background occupational science knowledge as well as their experiences from community outings to the Learning Studio. In the semester prior to OCS 372, the students had taken three occupational science courses that were loosely structured around the Person-Environment-Occupation model25. Knowing that students would bring their knowledge from those courses into the OCS 372, I isolated topics about human occupation that could link my students to international counterparts outside the U.S. The concept of culture dominated OCS 372 and bridged the students' knowledge of person, environment, and occupation, so 'culture' became a central focus of the international interactions that emanated from the course redesign. Given the need for "... a broader cultural emphasis in terms of curriculum delivery"3:328, the course redesign aimed to expand students' cultural competence beyond the opportunities offered by community outings. Cultural competence - or the idea that practitioners must be aware of and open to their clients' cultural backgrounds - has been a primary rationale for globalising occupational therapy education26,27. Although its importance is noted28,29, there is a lack of attention to the accompanying need for cultural competence between occupational therapists. Whereas parity in English and non-English definitions of occupational therapy constructs30 helps facilitate inter-therapist cultural competence, basic opportunities to talk with future professionals from other cultures is not a standard part of occupational therapy curricula. Given that globalisation and technology now increase the likelihood of interactions between international occupational therapists, the second phase of the course redesign aimed to give students opportunities for such interactions early on in the curriculum.

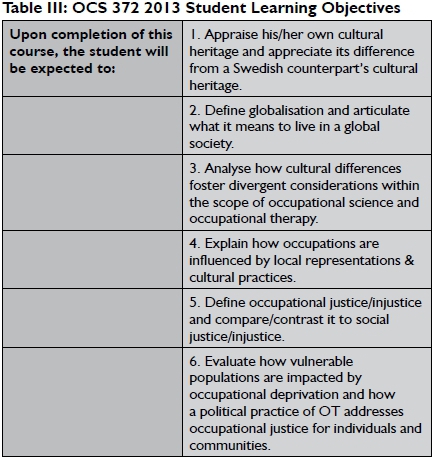

I designed real-time video-based interactive sessions to provide OCS 372 students with a means to achieve the learning objectives listed in Table 3.The decision to connect with Swedish students in particular for these interactions was primarily logistical: I had an existing relationship with occupational therapy faculty members at a Swedish university and knew that most classes at the Swedish university were conducted in English, thus removing the need for a translator during the interactions. I partnered with a Swedish colleague whose 5-week course about gender, class, ethnicity, culture, and occupation aligned with OCS 372 topics and was scheduled during the middle of the OCS 372 semester. Like my OCS 372 students, my colleague's undergraduate occupational therapy students were also in the second semester of their first year of core content, which enhanced the synergy between our courses. I assumed primary responsibility for designing the structure and content of our students' interactive sessions and worked with my Swedish colleague to refine that design and address logistical issues.

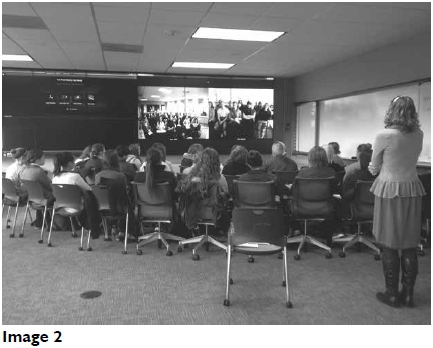

For the synchronous interactive sessions, students at each university were divided into two groups of 10-26 students for four weeks of interactions. One month prior to the first interactive session, I introduced the U.S. students to the concept of culture through course readings and discussion. The U.S. students also began reflecting on general characteristics of U.S. and Swedish culture based on excerpts from two Xenophobe's Guides books that "... take an analytical but affectionate look at different nations, their character and quirks" and "... pinpoint cultural differences (to encourage) awareness and understanding"31. In the week prior to the first interactive session, the U.S. students generated and answered any questions they had about Swedish culture, society, and occupational therapy practice during an in-class research session. Once the interactive sessions began in February 2013, each of the student group dyads "met" weekly for one hour to discuss readings and personal experiences related to culture, globalisation, occupational justice, and the political practice of occupational therapy. These meetings took place via web conferencing software that allowed the groups of students to see, hear, and speak to each other in real time (see Image 2).

The Swedish instructor and I developed and sent discussion questions to students in advance of the interactive sessions (see Table 4 for example questions). These questions were based on assigned readings, some of which were shared across the student groups and some of which were unique to each international context. My Swedish colleague and I acted as discussion facilitators for each interactive session, allowing conversations to unfold while also managing time during the sessions.

An example of dialogue from one session illustrates the nature of students' discussions. The topic for the day concerned the political practice of occupational therapy, and I opened the discussion by asking the U.S. students to describe what they thought of when they heard the words "politics" or "political." The U.S. students commented that "political" had to do with the government and had a negative connotation because it stimulated thoughts about arguments and power. When the same question was posed to the Swedish students, one Swedish student responded that "politics is everything" and involved how she and her friends were treated, how they spent their money, and how much public transportation cost. She ended her answer by stating that "politics" is "not something that somebody else does." This dialogue took only a few minutes to transpire, but in that short time, students on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean were able to see how different their perspectives were on a shared topic.

GENERATING AND ANALYSING DATA ON STUDENT PERCEPTIONS OF REDESIGNED COURSE ELEMENTS

Community outings

Roberts and Weaver argued that "... any evaluation study of the learning environment must include the learner perspective, underpinned by a critical enquiry approach"32:98. I drew information from anonymous end-of-course evaluations to understand the relation of community outings to students' learning. All 44 students enrolled in OCS 372 in 2012 completed the course evaluations, and 37 of the 52 enrolled students completed the course evaluations in 2013. Although the course evaluations included a quantitative component, none of the rating items could be specifically linked to the community outings, so I only gathered data from the open-ended section of the evaluation. The open-ended section included two questions of relevance to the community outings: "Please include any additional suggestions you have about the course structure" and "What might enhance the course?" Students answered the open-ended questions by typing their responses into a blank text box and electronically submitting their evaluations to the university. The results reported in the next section include frequencies of references to the community outings as well as summaries and verbatim answers to open-ended course evaluation questions; I did not conduct any qualitative or thematic analysis on the course evaluation data.

Synchronous online interactions

In 2013, I drew information from in-class reflective assignments and anonymous course evaluations to understand the relation of synchronous online interactions to students' learning. Of the 52 U.S. students in the 2013 course, 45 completed both reflective assignments and 37 completed the course evaluation. Given that the synchronous interactive sessions resulted from the redesign of the U.S. occupational science course, I only gathered data on the U.S. students' perceptions. In addition to the course evaluations, the U.S. students completed two reflections: one prior to and one following the four interactive sessions. The reflective assignments were structured loosely around a one-paragraph case that described an older woman who was in the hospital following a hip fracture. The case was borrowed from an MOT course and simplified for the purposes of studying this course redesign. I never discussed the case and the students had little knowledge of clinical material, so the open-ended reflective questions related to the case took a broad focus (see Table 5 on page 60). The case presented basic information related to occupation and occupational therapy, and the intent of the reflective questions was not to elicit responses about treatment per se but to see whether students grew in their understandings of the cultural and political concerns that inform occupational therapy in different global contexts. The students answered the reflective questions in class and electronically submitted their typed reflections to an online storage folder that the instructional designer had set up. The instructional designer assigned each student a numeric identifier, labelled the reflection sets with those numeric identifiers, and granted me access to the storage folder once I had submitted the final grades for the course. While analysing each set of reflections, I counted the number of references to a particular course element (e.g., community outings or synchronous international online interactions) and summarised the content of students' qualitative responses. In addition to frequencies, I report content summaries and verbatim answers to the course evaluation and reflective questions in the next section; as with the 2012 data, I did not conduct any qualitative or thematic analysis on the data. The university's Institutional Review Board approved all data collection and analysis as outlined above.

RESULTS

2012 data

Per the 2012 course evaluations, the community outings successfully brought the OCS 372 content more fully into students' realities. One student wrote that the experiential ... outings were very informative and allowed us to see first-hand what we are discussing in class, and another student noted that the outings ... tied in nicely with our class readings and discussions. Learning in the community, [as] opposed to reading about [it] in the classroom and readings, was a positive learning tool.

Yet another student noted that the community outings ... were a great addition to relevant course topics making it a more memorable experience. One student commented, ... I think that the experiential outings are what really helped me tie-together all the concepts we learned in this class. Several student comments also reflected the sentiment that ... the reflection papers helped me to understand the course concepts. In all, 19 open-ended comments conveyed positive perceptions of the community outings as vehicles for learning.

Students also made suggestions for how to improve the experiential outings. Six students requested additional outings, because, as one student explained: ... most students come from closed environments and haven't had much experience with "the others". A real awareness needs to be established in our students to help them gain a better, diverse way of thinking. It's a reality check that is needed for our generation. Nothing is better than experiencing a phenomena (sic) for one's personal life journey.

Another student said that ... more outings would be a great way to further engage in the topic of culture and I think it would help make the concepts a lot more clear. Yet another student suggested placing ... outings earlier in the semester to really understand what we're learning about the entire semester. Such comments suggested that the community outings had a positive impact on students' learning, and I scheduled the 2013 outings earlier in the semester in response to such feedback.

2013 data

In the 2013 OCS 372 course evaluations, five open-ended comments addressed the community outings and six addressed the synchronous international interactive sessions. Regarding the outings, students' echoed the positive comments from the 2012 course evaluations. One student wrote, ... I loved our class outings, I really wish we could have had more ofthose experiences. Listening to the community speak in those situations was such a learning experience for me.

Another student noted, ... I thought that the experiential outings were extremely powerful and made a large impact in my understanding of the course material. Providing more options and opportunities for those experiences to see the illumination of course concepts would also allow students to create that connection from class discussion to the real world.

Although one student noted that the outings ... helped me be aware more of what is going on in my surroundings, students also highlighted a desire for easier transportation to and from outing sites as well as more time to reflect upon the outings in the university classroom. Perhaps in reference to both the community outings and the synchronous online interactive sessions, one student wrote that ... this course opened my eyes to so many different ways of looking at the world. Regarding the synchronous interactive sessions, two students conveyed a wish to ... spend more time talking to the Swedish students. Two comments highlighted a perceived difference between the U.S. and Swedish students in terms of preparation for and participation in the interactive sessions, and those comments changed the ways in which my Swedish colleague and I prepared our respective classes for the interactive sessions in 2014.

In the 2013 case-based written reflections, over 50% of the students referenced the synchronous online interactive sessions as influential for helping them answer the reflective questions. The interactive sessions were mentioned 21 times across student responses, versus six mentions of the community outings, six mentions of class discussions, and three mentions of class readings. Several quotations from students' reflections illuminate why students perceived the interactive sessions as helpful for their learning. One student said, ... This was a real life situation that taught about different context, cultures, norms, and the different ways that OT is practised. While reading articles and discussing is a great tool, it is much more impactful to have real people from a different country telling you how it really is.

Another student noted that, ... I believe that our interactions with the Swedish students helped to open up my eyes to experiencing different cultures. Traveling is something I've always wanted to do, but I've never had the money to go. This experience gave me an opportunity to gain knowledge of a different culture without actually having to be there.

Yet another student said that ... having the Swedish students interact with us through webcam was a wonderful way of learning about different cultures and understanding their value systems. Having this interaction has helped me realise how this can be arranged and that it is another possible way of learning.

As evidenced by the data, many students perceived that the synchronous online interactions were more significant for their learning than other course elements because the interactions gave the students access to information that they might not have had otherwise; however, the students also linked the interactive sessions to their community outings and recognised the importance of the outings in their own right as new ways of learning. One student commented that ...talking with the Swedish students, and understanding through the class outings that there are different cultural practices and values even in cities like [ours] has most significantly helped me answer these questions.

Another student said that ... I think that getting to go on two outings during class really made me aware of all the diversity and how to appropriately handle it within our own city was very helpful. I also think that getting the chance to talk to the Swedish students was also beneficial to learn a different perspective.

The students also saw the experiential outings as important in and of themselves, as well. One stated, ... By going on these outings I was able to see first-hand how the different course topics affected people. I better understood what we were learning when I was able to apply it to a group of people. Having specific examples that I could pull clarified what we were learning and class and enriched the experience.

Another student wrote that ... These outings have greatly impacted the way in which I view the community around us. It was interesting to view the difference in populations just outside of our campus walls. It leads me to believe that gathering research about different populations and cultures cannot necessarily always be done only from the classroom.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Although the U.S. students had limited engagement with community members and Swedish peers due to the introductory nature of the outings and online interactive sessions, these experiential learning opportunities appeared to represent a novel and important form of engagement for most students. Jeffery10 asserted a fit between experiential learning, occupational therapy's core philosophical roots, and the profession's current focus on producing change agents who seek justice. Schaber, Marsh, and Wilcox13 also noted the salience of experiential learning as a "signature" pedagogical approach in occupational therapy education. Positive student feedback regarding both elements of this course redesign adds another voice in support of experiential learning in occupational science and occupational therapy education. Although student feedback mechanisms did not lend themselves to a specific focus on what students learned about human occupation, they did indicate that experiential learning helped students solidify and apply understandings related to culture. This pilot project affirms recent findings from other universities that local and global experiential learning can increase occupational therapy students' perceived understanding of culture and its impact on occupation and occupational therapy practice21.

Jeffery argued that "... the educational aspect of [experiential learning] is dependent on the level of processing involved during and after the experience"10:6 and that a crucial part of experiential education occurs when "... the teacher actively encourages or enables critical reflection on the experience"10:8. The findings from this pilot project indicate that students valued the structured reflections associated with experiential learning opportunities. The need to create more opportunities for students to experience and reflect on what they learn requires educators to be more explicit about how, why, where, and what they teach. Whereas other experiential approaches such as problem-based learning have solid grounding in the occupational therapy literature15, approaches that focus on community and technology-rich learning spaces are not well detailed in existing scholarship. Accordingly, student feedback on this course redesign provides encouragement for educators to share how they utilise novel learning spaces and reflective processes in occupational science and occupational therapy programmes.

Student feedback suggests that having opportunities to apply occupation-related concepts through local and global learning provides benefits beyond traditional instruction alone. Given that the pool of occupational science authors has become increasingly global in recent years33,34, it is likely that opportunities for international student interactions vis-à-vis occupation-related concepts will only become more feasible in the future. A broad foundation in occupational science enabled the U.S. students to dialogue and learn with international peers about a range of topics without the need for detailed knowledge of occupational therapy practice; hence, this pilot course redesign showed that experiential learning can occur relatively early in occupational science and occupational therapy students' educational programmes. Early, non-clinical exposure to local and global issues related to occupation gives students time to form habits of thinking and communicating that they can refine throughout their education and practice. Jeffery, who has stressed the importance of experiential learning as a vehicle for socialising occupational therapy students into professionals, noted that

"...developing an awareness of the "big picture" and concepts of the occupation at a societal and global level ...can be described as developing action competence within the areas of direct interest to the profession (unemployment, poverty, homelessness, occupational deprivation, etc.). This process is potentially enabled by education principles that incorporate concepts such as nurturing and developing self- awareness, empowering learners to critically construct knowledge from core values of the profession, and having direct meaningful experiences within the communities of interest"10:11.

Thus, as educators explore opportunities for experiential learning about occupation, they must do so with an eye toward the types of occupational therapy professionals they want to shape.

Regarding the logistics of local and global experiential learning, considerations related to infrastructure are key. Connecting with community members to schedule outings takes time, and advance planning is required to safely transport students to and from community sites. The infrastructure for synchronous international online interactions is more complex. Given the ubiquity of technology, synchronous online interactions can occur with little direct cost if internet access (and sufficient bandwidth), a web camera, microphones, and speakers are present on a university's campus. However, dedicated course design support and planning is essential to ensure that the where and how of synchronous online interactions match why and what students learn in a course. The course release and instructional design support I received through the Innovative Teaching Fellowship were essential to matching my teaching goals with experiential learning activities, technology use, and student learning outcomes. Likewise, having time within OCS 372 to prepare the U.S. students for the experiential outings and synchronous interactions and help them reflect on those experiences was important to the learning that resulted from those experiences. Planning with my Swedish colleague for the interactive sessions also required significant work over a long period of time, and departmental support to evaluate and refine the experiential learning opportunities has been vital to their continued success in subsequent iterations of OCS 372.

Aside from attention to planning and infrastructure, it is important to consider how experiential learning might unintentionally privilege certain perspectives. Local community partners with limited resources may not be able to host student groups, and the internet bandwidth needed for synchronous online interactions is not a guaranteed amenity at all universities. The pedagogical approach described in this article may thus inadvertently privilege perspectives from more affluent local organisations and global regions. Accordingly, occupational science and occupational therapy educators must be vigilant in examining which perspectives are privileged by experiential learning and how to avoid inadvertently excluding partners from particular places due to infrastructural constraints.

Future directions

Both redesigned course elements continue to be used in OCS 372. Based on the results of the 2012 and 2013 data, I added community guest speakers to the course to give students additional opportunities to discuss their local experiential learning. My Swedish colleague and I also collected data from both U.S. and Swedish students in 2014, the analysis of which is ongoing. In subsequent iterations of OCS 372, I aim to add interactive sessions with occupational science and occupational therapy students from other parts of the world, particularly the global South.

CONCLUSION

Local and global experiential learning can positively impact students' learning about human occupation if structured opportunities for reflection are provided. As educators pursue experiential learning opportunities, it is important to consider how experiential education fits within a course's overall design and objectives. The time is right for educators to use concepts related to human occupation as a platform for local and global experiential learning. However, such uses must attend to infrastructure and support needs without ignoring the possibility that pedagogical platforms may indirectly exclude certain local and global voices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Parts of this article have been presented at the following conferences: the 2014 International Congress on College Teaching and Learning; the 2014 Congress of the WFOT; and the 2014 Joint Conference of the Society for the Study of Occupation: USA; the Canadian Society of Occupational Scientists and the International Society for Occupational Science. I am indebted to Jerod Quinn, who worked with me not only to design and execute the synchronous online international interactions but also to help me re-imagine my teaching on a broader scale. I am also grateful to Debie Lohe and the rest of the Reinert Centre for Transformative Teaching and Learning for the opportunity to hold the Innovative Teaching Fellowship and teach in the Learning Studio. Many thanks to Debra Rybski for sharing her original OCS 372 course materials with me as I began this redesign process, and to Lenin Grajos for his insightful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Finally, I appreciate Karin Johansson, our students, and my community partners for their willingness to embark on this adventure.

REFERENCES

1. Ritzer G. Globalization: A Basic Text. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. [ Links ]

2. Thibeault R. Globalization, universities, and the future of occupational therapy: Dispatches for the Majority World. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2006; 53: 159-165. [ Links ]

3. Westcott L, Whitcombe SW. Globalization and occupational therapy: Worlds apart? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2003; 66: 328-330. [ Links ]

4. Kinsella EA, Bossers A, Ferreira D. Enablers and challenges to international practice education: A case study. Learning in Health and Social Care, 2008; 7: 79-92. [ Links ]

5. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Position statement: Occupational science - revised. 2012. <http://www.wfot.org/aboutus/positionstatements.aspx> (4 April 2014) [ Links ]

6. Whiteford G, Townsend E. Participatory Occupational Justice Framework (POTJ): Enabling occupational participation and inclusion. In: Kronenberg F, Pollard N, Sakellariou D, editors. Occupational therapies without borders: towards an ecology of occupation-based practices. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2011:65-84. [ Links ]

7. Pollard N, Kronenberg F Sakellariou D. A political practice of occupational therapy. In: Pollard N, Sakellariou D, Kronenberg F editors. A political practice of occupational therapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2008:3-19. [ Links ]

8. Aldrich R Marterella A. Community-engaged research: A path for occupational science in the changing university landscape. Journal of Occupational Science, 2014, 21: 210-225. [ Links ]

9. Pappas, G. John Dewey's ethics: Democracy as experience. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. [ Links ]

10. Jeffery H. Student-centred learning: Options for the application of constructivist thinking in occupational therapy education. WikiEdu-cator.org, 2010: 1-15. <http://wikieducator.org/File:Jeffrey20l0_Student_centred_learning_-_theory-based_options_for_applica-tion_in_OT.pdf> (25 January 2014) [ Links ]

11. Cutchin MP Using Deweyan philosophy to rename and reframe adaptation-to-environment. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 58: 303-312. doi: 10.5014/ajot.58.3.303 [ Links ]

12. Hooper B, Wood W. Pragmatism and structuralism in occupational therapy: The long conversation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2002; 56: 40-50. doi: 10.5014/ajot.56.1.40 [ Links ]

13. Schaber P Marsh L, Wilcox KJ. Relational learning and active engagement in occupational therapy professional education. In: Chick NL, Haynie A, Gurung RAR editors. Exploring more signature pedagogies: approaches to teaching and disciplinary habits of mind. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, 2012:188-202. [ Links ]

14. Reinert Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning. "Ignatian Pedagogy Overview." No date. <http://www.slu.edu/cttl/resources/ignatian-pedagogy> (4 April 2014). [ Links ]

15. Hooper B, King R Wood W, Bilics A, Gupta J. An international systematic mapping review of educational approaches and teaching methods in occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2013; 76: 9-22. doi:10.4276/030802213X13576469254612 [ Links ]

16. American Occupational Therapy Association. Report on the findings of the survey on scholarship and research in occupational therapy education. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2012. [ Links ]

17. American Occupational Therapy Association. Scholarship and research on occupational therapy teaching and learning: Report to AOTA ad hoc Committee for Future of OT Education. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2013. [ Links ]

18. Trujillo LG. Distance education pedagogy and instructional design and development for occupational therapy programs. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 2007; 21: 159-174. [ Links ]

19. Hollis V Madill H. Online learning: The potential for occupational therapy education. Occupational Therapy International, 2006; 13: 61-78. [ Links ]

20. Armitt G, Slack F Green S, Beer M. The development of deep learning during a synchronous collaborative online course. CSCL 2002 Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Support for Collaborative Learning: Foundations for a CSCL Community, 2002: 151-159. [ Links ]

21. Sood D, Cepa D, Dsouza SA, Saha S. Impact of international collaborative project on cultural competence among occupational therapy students. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2014; 2. [ Links ]

22. Taylor SS. Effects of studio space on teaching and learning: Preliminary findings from two case studies. Innovative Higher Education, 2009; 33: 217-228. [ Links ]

23. Temple P Learning spaces in higher education: An under-researched topic. London Review of Education, 2008; 6: 229-241. [ Links ]

24. Walker JD, Brooks DC, Baepler P. Pedagogy and space: Empirical research on new learning environments. Educause Review Online, 2011. < http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/pedagogy-and-space-empirical-research-new-learning-environments> (4 April 2014) [ Links ]

25. Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, Stewart D, Rigby P Letts L. The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1996; 63: 9-23. [ Links ]

26. Awaad T. Culture, cultural competency, and occupational therapy: A review of the literature. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2003; 66: 356-362. [ Links ]

27. Iwama M. Culture and occupational therapy: Meeting the challenge of relevance in a global world. Occupational Therapy International, 2007; 14: 183-187. [ Links ]

28. Bonder BR, Martin L, Miracle AW. Culture emergent in occupation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 58: 159-168. [ Links ]

29. Dickie VA. Culture is tricky: A commentary on culture emergent in occupation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 58:169-173. [ Links ]

30. Creek J, Rivero MB, Faias J, Meyer S, Pitteljon H, Stadler-Grillmaier J. Developing culturally appropriate language for occupational therapy. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2010 (supplement): 6-8. [ Links ]

31. Xenophobes.com. About the guides. <http://www.xenophobes.com/about-the-guides/> (26 November 2014). [ Links ]

32. Roberts S, Weaver W. Spaces for learners and learning: Evaluating the impact of technology-rich learning spaces. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 2006; 12: 95-107. doi: 10.1080/13614530801330380 [ Links ]

33. Molke DL, Laliberte Rudman D, Polatajko HJ. The promise of occupational science: A developmental assessment of an emerging academic discipline. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2004; 71: 269-281. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100505. [ Links ]

34. Glover JS. The literature of occupational science: A systematic, quantitative examination of peer-reviewed publications from 1996-2006. Journal of Occupational Science, 2009; 16: 92-103. doi:10.1080/14427591.2009.9686648. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Rebecca M. Aldrich

raldrich@slu.edu