Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.45 n.1 Pretoria Jan./Apr. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45no1a9

SECTION 1

An introduction to Cultural Historical Activity Theory as a theoretical lens for understanding how occupational therapists design interventions for persons living in low-income conditions in South Africa

Pam GretschelI; Elelwani L. RamugondoII; Roshan GalvaanIII

IB OT (US), M ECI (UP). Lecturer, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIBSc OT (UCT), MSc OT (UCT), PhD OT (UCT). Associate Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIBSc OT (UCT), MSc OT (UCT), PhD OT (UCT). Associate Professor and Head of Division, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) is a cogent conceptual tool to guide thinking about, observations of and analyses of what people do. This article offers an introduction to the basic tenants of CHAT. It describes how CHAT can be applied as a meta-theory in a case study, which explores the processes by which a group of occupational therapists designed a new occupational therapy intervention for caregivers of HIV positive children living in low-income conditions in South Africa. Drawing on CHAT this paper proposes that occupational therapy intervention design could be viewed from a collective and also a historical and socio-cultural perspective. This allows for the discovery and analysis of the potential enablers and limits to innovative, relevant and critically considered occupational therapy interventions in the South African context.

Key words: activity theory, occupational therapy, intervention design, HIV/AIDS, children, action research

INTRODUCTION

Intervention design is a key component of occupational therapy processes. Occupational therapists craft interventions aiming to respond to people's occupational needs. Occupational therapists' intervention design processes often foreground the intended recipients of the interventions, giving little attention to the occupational therapists and their situated processes when designing interventions. Thus the occupational therapists' occupation(s) of designing interventions for the people they work with is not extensively considered as a unit of analysis. The traditional focus in occupational therapy literature and practice has centered on a categorical exploration of occupational therapists' individualized cognitive processes of clinical and professional reasoning1. While valuable, this focus fails to attend to the contextually situated reasoning that emerges from the appreciation of the situational nature of intervention design as an occupation for occupational therapists1. Appreciating the transactional nature2 of the occupation (s) of intervention design, the use of CHAT as an analytical lens, draws attention to the influence of the individual therapist's position in and experience of living and working in a particular context, inclusive of the sociocultural and historical traditions present in that context.

Occupational therapists, much like the persons that they work with, are embedded in and intricately connected to the contexts in which they live and work. They are professionally socialised and enculturated by the socio-cultural influences within their contexts, shaping the meaning that they ascribe to their actions3. A particular enculturation may also exist due to the dominance of a homogenous race and gender group, that is white females within the occupational therapy profession and a resultant unilateral knowledge base4,5. Occupation often features centrally in an occupational therapy intervention, both as a means and an end6. Viewing intervention design as both an occupation for occupational therapists and an interchange between occupational therapists and those persons that they work with, as shaped by their social-cultural positioning, warrants exploration. The cultural historical lens of CHAT can be used to analyse this complex, collective and contextually situated nature of occupational therapy intervention design processes.

Toth-Cohen used CHAT as an analytical tool to unpack areas of conflict and congruence within the clinical and professional reasoning processes of occupational therapists delivering home based intervention for caregivers of clients with dementia1. This article supports Toth-Cohen's1 use of CHAT to extend beyond an individualised to a collective and situated perspective of the clinical and professional reasoning informing the design of occupational therapy interventions. Further to this, it draws on CHAT to propose a historical and socio-cultural perspective of occupational therapy intervention design. A case of one group of occupational therapists tasked with designing a new intervention targeting caregivers of HIV positive children in South Africa will be used to illustrate CHAT as analytic tool for discerning intervention design as an occupation of occupational therapists. The intervention aimed to improve both caregiver and child's participation outcomes. Such a perspective of intervention design activity has not been previously identified within the occupational therapy discourse.

INTRODUCING THE CASE STUDY INTERVENTION DESIGN PROCESS AND THE THEORETICAL LENS OF CHAT

The case study intervention design process

Childhood HIV infection is of paramount concern in South Africa7- The majority of HIV infected children in South Africa live in low-income conditions7. HIV places children at great risk for developmental, play and learning difficulties and its interrelationship with negative social circumstances exacerbates this risk8-10. In 2012 a group of four occupational therapists working for a nongovernmental organisation (NGO) were tasked with designing a new play informed caregiver implemented home based intervention (PICIHBI) targeting caregivers of children on highly active anti-retroviral treatment (HAART) in South Africa. The first author's doctoral study drew on a Case Study design11-14 to explore the process by which this group of occupational therapists designed this intervention. The group which grew to seven occupational therapists, included the four occupational therapists who commenced the intervention design process, two occupational therapists who joined the group at a later stage as intervention designers and the first author, the principle investigator of the doctoral study, who worked together with the group to both observe and participate in the intervention design processes.

Over a 20-month period the first author joined the group's intervention design meetings as a co-designer and researcher-observer focusing in particular on how we as a group both created and drew on existing knowledge to guide the intervention design. Co-operative Inquiry, a form of action research15 was used to ensure methodological rigour. Co-operative inquiry enabled the productive practices of intervention design to emerge during a series of once to twice-monthly intervention design meetings over the 20-month period. This research design-methodology combination helped the first author frame the occupational therapists and intervention design process as a bounded case, in which situated and/or complex relationships could be identified and worked on, where possible, in the cyclic process of the intervention design meetings. Beyond the communicative interchanges of a group process, the first author noted increasingly the many historically located socio-cultural factors at play, impacting on the intervention design process. These observations prompted questions of both her self and the group about the influence of our social and professional positioning on our intervention design processes; the physical and conceptual tools we drew on to inform the design of the intervention; the rules and division of labour inherent in the intervention design processes; the successes and contradictions within the processes as well as our actions taken in response to these successes and contradictions.

Case Study explored the intervention design activity asking: What are the subjects doing and how are they doing it?11-14. CHAT explored further the observations unpacked by the Case Study design asking also: Why does this action occur and/or what influences result in this action?"16-18.

The theoretical lens of CHAT

CHAT provided the theoretical lens for reflecting on these and other questions. It helped to understand not only what the process was, but also the historical, economic, political and social cultural factors constituting such a process16. CHAT is a theoretical lens derived from German philosophy and Russian social science theory16. It is widely used as a descriptive theory to describe the activity of people. The acronym CHAT is extended as follows: 'Cultural' positions humans-the subject of activity theory - as beings shaped by their cultural views and resources. 'Historical' highlights the inseparable influence of our histories on our actions, and how this history shapes how we think. 'Activity' refers to the doing of people, together, that is modified by history and culture, and situated in context. 'Theory' refers to the conceptual framework that activity theory offers for describing and understanding human activity16.

Activity as a construct

To avoid conceptual confusion, a brief differentiation of the term activity as represented by activity theorists, the profession of occupational therapy and the discipline of occupational science is offered. Scholarship in occupational therapy has not theorised extensively about the construct of activity, reflecting a dominant interest in the performance components needed to support the successful execution of an activity. Occupational scientists such as Pierce refer to activity as a " ... general and culturally shared idea about a category of action"19,13,8. For example eating is an action, which can be widely understood and undertaken by individuals. The construct of occupation in the occupational therapy profession and occupational science discipline draws attention to a specific individual's personally constructed, non-repeatable experience of an activity18, thus attending to each person's specific engagement in and experience of eating.

CHAT views activity in an activity system as the collective, object-orientated, tool-mediated actions of a group as influenced by culture, history, economics and / or material things16. It unpacks the multiple layers of a process that is aimed at constructing an object. In this way it represents the complexity of the whole activity but allows for an analysis of the components of the activity system and the multiple dimensions of culture, history and economics at play in the activity system in a point or over time16,20. The construct of activity in activity theory is centered on the creation of an object and thus it is the object-orientated nature of human activity that defines the term activity in activity theories21,22.

The activity system

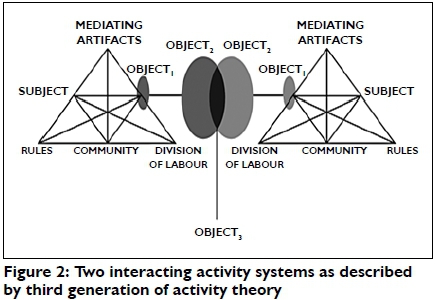

In CHAT the unit of analysis is the activity system. In Figure 1 Engestrom's activity systems model22 based on Leontiev's work on the collective nature of human activity17,18,21, is presented to illustrate the six components of an activity system. In the uppermost triangle, collective activity is reflected as the action/s undertaken by people (subjects) who are motivated by a purpose or towards the solution of a problem (object), which is a process mediated by tools used in order to achieve the goal (outcome). The lower three triangles extended on and introduced by Engestrom22 highlight how the collective activity of the subjects is influenced by cultural and socio-historical factors including conventions (rules) and social organisation (division of labour) within the immediate context and framed by broader social patterns inherent in the community in which the activity exists. The intersecting arrows within the triangle highlight the reciprocal relationships between the elements of an activity system.

Engestrom's third generation activity theory23 explores the nested nature of an activity system within other activity systems and describes also how one activity system can connect to other activity systems through all of its components. Such a conceptualisation highlights the differing viewpoints, values and resultant congruences or incongruences that may occur as a result of the interactions between two or more activity systems and the object/s that may result from these interactions20. Examples of these interactions in the Case Study activity system are illustrated briefly in this article and will be extended on in future publications.

Interconnected concepts within an activity system

In addition to the components of an activity system, three interconnected concepts can operate in an activity system and can inform all of the components of the activity system. These concepts are heterogeneity; historicity; and contradictions, discontinuity and change.

❖ Heterogeneity refers to the multiple viewpoints and perspectives, each having its own history and potential, which exist in any activity system and which can operate to create a platform for varied engagement. The multi voiced nature of heterogeneity can bring both conflict and innovation into any activity system24.

❖ Historicity refers to the history that is present in the activity system within the individual participants and within the mediating tools and rules24 existing in the activity system. Engestrom states that the "... problems and potentials of activity systems can only be understood against their own history"24137.

❖ The life of an activity system can also be underscored by contradictions, discontinuities, upheavals and qualitative transforma-tions22. These are the events, which can promote or hinder the process of the activity system towards its intended outcome.

CULTURAL HISTORICAL ACTIVITY THEORY- A META-ANALYTICAL LENS FOR UNDERSTANDING OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY INTERVENTION DESIGN

In order to highlight the analytical properties of CHAT, its application to the Case Study introduced above follows. In this application each of the six components of an activity system and the three interconnected concepts of an activity system will be further described to illustrate the potential value of CHAT to analyse occupational therapy practice.

Locating the subject

The subject/s is the person or people who are directly participating in the activity within the activity system studied. In the Case Study activity system, the subjects are the occupational therapists involved in the process of designing the object (the PICIHBI). The viewpoints of the subjects were studied when analysing their practices of designing the intervention in context. CHAT recognises that each subject's past professional and personal experiences as well as their positions in society, work and family influence their construction of the object of the activity. The seven occupational therapists constituted a homogenous group in that we were all female and predominantly white race. Only one therapist was coloured- one of the race classifications formed under Apartheid, describing individuals with creolised identities shaped and re-shaped by current and historical practices in South Africa25. All of the occupational therapists were of mid to upper socioeconomic class positioning, all had tertiary education, having all obtained a bachelors degree in Occupational Therapy at the same university, and all were first language English speaking. Four of the seven occupational therapists were mothers. South Africa is an economically, culturally and socially stratified country inhabited by a diverse population group. The country's unique political history has created distinct socio cultural margins. A homogenous group of white South African occupational therapist needs to consider that the elements of meaning and purpose that they attach to occupational engagement may differ to that of the people that they work with. CHAT provides the lens to guide this consideration.

Building on situated learning and community of practice theories26, CHAT delved deeper into the impact of the situational aspects that shaped the collective journey of the subject occupational therapists. It acknowledges that aspects of power and power relations can never be excluded as influences on human activity and in this way provided a useful analytical tool to explore these relations27-30. While issues of power have been considered in occupational therapy literature31, relational factors arising from the socio-cultural and historical positioning32 of the occupational therapy profession and occupational therapists have not been duly considered as influencing the design of occupational therapy interventions. A CHAT lens allowed exploration of these historically located socio cultural positional factors through questions such as: Where do we as occupational therapists come from as people and professionals? How do these origins position us in the process of designing the intervention? These are factors which have not been duly considered as influencing the design of occupational therapy interventions.

Locating the object

The object, the second component of an activity system, is the problem space towards which the subjects address their activity. The analysis of the object of the activity system is critical to understanding the activity of an individual or group of individuals16, in that it is the object that "... determines, directs and distinguishes each activity system"18:50. The object in an activity system is conceptualised in three different ways. Firstly, the object is the raw material or the thing-to-be-acted-upon that is, the caregiving, play, learning and developmental challenges as observed by the occupational therapists in their practice settings. This raw material drove our need to create a responsive intervention. Secondly, the object is the objectified motive, our intent to address the occupational performance and occupational engagement challenges of both the children and their caregivers. Thirdly, the object is a desired outcome, our aim to create an intervention that improved these identified occupational challenges. In CHAT, the object has all of the above facets, and any of these facets may be constructed or perceived differently by each of the subjects.

Heterogeneity within an activity system and across interacting activity systems

While developments in occupational therapy literature delineating collective occupation33, collaborative engagement34 and collective participation35 are useful in exploring the collective activity of this group of occupational therapists, these constructs have not been substantially theorised and are inadequate as a framework for exploring the object-orientatedness of this Case Study activity system. Activity theory offers one way of understanding the occupational therapists' collective, object-orientated processes of working together to design the new intervention aiming to improve child and caregiver participation outcomes16,21,32,36. The process of object formation within an activity system arises from a state of need or "need state"34:138 serving as the motive/s directing the subject's activities. In this case we as a group were tasked with designing a new intervention, the PICIHBI. CHAT attended to and considered the differing and similar motives of each of the subjects related to their cultural and historical positioning and how this impacted on their actions within the intervention design activity system. CHAT explored elements of heterogeneity within the group of occupational therapists, or possible lack thereof, asking if and how our possibly similar perspectives linked to our homogenous race and social positioning limited the possibilities of the object (intervention) constructed.

CHAT also explored the differing motives and associated contributions of the subjects linked to their involvement in other activity systems. Four occupational therapists in the group were pursuing Masters' studies aiming to explore the efficacy of the PICIHBI on various child and caregiver participation outcomes. Their research process and foci was considered in terms of how it would drive different agendas with respect to the intended outcomes of the intervention designed. CHAT also guided an exploration of my differing motives and contributions in my dual role as a researcher and co-designer of intervention.

Third generation activity theory23 offers an extended view of the interaction of activity systems and the way in which two or more activity systems may interact to form new objects and outcomes. The first author drew on third generation activity theory to explore and analyse interactions and outcomes of interactions between the intervention design activity system and other activity systems, which included amongst others the caregiver and child activity system, the parallel research activity system of the four students, and the work place settings of the subjects. These interactions will be presented in future publications.

Historicity: within the object created and the mediating tools and rules drawn on to create the object

Mediating tools, the third component of an activity system, are the tools that mediate the relationship between the subject and the object. The subject(s) use tools to accomplish their object(ives) and achieve their intended outcomes. They are motivated to use these tools because they want to accomplish something and the tools help them do so. Tools can be the conceptual and/or physical tools of practice used by the subjects. As mentioned earlier, history is present in the activity system within the history of individual subjects and within the tools24. Using CHAT, the first author explored the tools the subjects drew on and how these tools were accessed, used and adapted to inform the design of the PICIHBI. During the intervention design meetings the first author asked questions to gain access into the subjects' implicit motivations driving the use of the tools they selected to inform the design of the intervention. Within this component, the first author keenly observed how the group would negotiate the paucity of available research evidence to guide the design of this intervention in an era promoting evidence based practice.

The creative potential of the activity is closely related to the subjects' capacity to construct and redefine the object37:380-381. The construction of the object is related to the cultural historical properties of that object. In this Case this would be the traditional ways in which occupational therapy interventions for children have been designed within the profession. CHAT allowed an exploration of the ways in which the group created a more novel intervention asking how and in what ways we adopted new ways of understanding and responding to the developmental, play and learning needs of the children, as well as the occupational needs of caregivers?

The social basis of the activity system: community, rules and division of labour

Community refers to people who share the same problem space as the subjects in that they are also invested in the object orientated nature of the subject's activity system. The community is the larger group that the subjects exist in and is described to exert a powerful influence on the other elements of the activity system32,38. In this study, the community included, amongst others, the occupational therapists' families, the caregivers and children they worked with, the clinic staff at their workplaces, their research supervisors and the funders with whom they interacted. They formed the multiple communities of people directly or indirectly linked to the intervention design activity system. CHAT explored the influences of these communities on the group's process of designing the intervention allowing an inquiry into how the communities either supported or hindered the intervention design process. CHAT also explored the communities that the subjects privileged in that they drew cues more consistently from these communities.

Social and professional rules refer to the norms, conventions and social interactions driving the subjects' actions32,38. This activity system was complicated by a vast interplay of varying and often contesting professional and social rules. Professional rules referred to the philosophical tenants and professional guidelines of the occupational therapy profession and how these informed the intervention design. Rules affected the activity and were imposed on the subjects by the communities in which the subjects' activity existed. For example the subjects were nested in a medical environment in which they often had to juggle medical orientations with their attention to the socially positioned occupational needs of the caregivers and their children. The demands of the NGO that many of the subjects worked for, as well as the other subjects' workplaces impacted on their activity of designing the intervention. Social rules are the informal rules, which govern our interactions with others. CHAT was drawn on to explore the impact of social rules on the ways in which the group would interact and gain knowledge from the children, the caregivers, their research supervisors and each other as well other persons within the activity system to inform the design of the intervention. CHATguided the first author to observe how these rules governed our intervention design practices; the ways in which we critically considered the negative or positive impact of these rules and if and how we worked within or against the influence of these rules.

Activities usually involve a division of labour32,38. This is the way in which tasks are negotiated between the subjects in the activity system and the larger community in which the activity system exists, through a set of tacit and explicit rules. The subjects negotiated many tasks and responsibilities. They were faced with the varied tasks of designing the intervention, developing protocols for their postgraduate master's studies, fulfilling their responsibilities in their work contexts and liaising with various donors for funding. Division of labour within the group and between the group and organisations they linked and the way that the delegation of and responsibility for tasks was decided upon, was explored through CHAT drawing on questions as to why such divisions of labour existed, whether concerns arose around the division of labour and what was done to address concerns within the division of labour.

INTERVENTION DESIGN: AN ACTIVITY SYSTEM REVIEWED

Drawing on the information provided above detailing the analytic utility of CHAT, the authors encourage readers to consider the multiple elements at play in their activity system of designing occupational therapy interventions. The following questions guide a consideration of the elements of an intervention design activity system and the relationships between these elements:

❖ SUBJECTS: Who are we as subjects? Does who we are as people and professionals impact on the interventions we design?

❖ OBJECT: What is the object of our intervention design activity? What is our intended outcome for this object?

❖ TOOLS: What tools do we use to design interventions? Why do we use these tools? Are they the most appropriate tools? Do we need to extend on the tools that we use?

❖ RULES: What laws, policies, codes and practices govern our intervention design activity? What influence do these rules have on our activity?

❖ COMMUNITY: Who are the communities we work with? In what ways are they engaged? How do they influence our activity?

❖ DIVISION OF LABOUR: How are tasks divided? Why are they divided in this way? Does the division result in any conflicts?

CONCLUSION

Designing occupational therapy interventions forms an essential part of the doing of occupational therapists. The process by which occupational therapists do this is complex and suitable theories are needed to understand the contextually situated nature of this historically located, collective and socio-culturally mediated activity. CHAT provides a well-suited lens that recognises that what people do cannot be separated from the influence of context and aspects of power and power relations inherent in the context. CHAT dia-lectically links the individual and the social structures in which they exist, attending to not only the interpersonal and communicative behavior of individuals but also the historical, economic, cultural, political aspects shaping the object orientated-ness of the activity. For occupational therapists CHAT attends to both the internal mental processes of occupational therapists (use of evidence, clinical and professional reasoning and generation of knowledge) as well as the social and physical environment and the interactions between these elements in the intervention design activity system and other interrelated activity systems. Activity theory's focus on the intricacies and multi-dimensional layers of an intervention design process can help uncover and address the ways in which occupational therapists, especially those working in South Africa, develop interventions which serve their clients and communities best.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article draws on data generated in an ongoing research project as part of the requirements for a Doctoral study in Occupational Therapy, in the Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. Acknowledgements are made to the DG Murray Trust and the National Research Fund (Thuthuka Programme) for enabling the research within which the PhD study is situated. The Medical Research Council of South Africa and National Health Scholars Program have provided funding support for this study. HREC: 605/2012. The occupational therapist co-researchers are thanked for their willingness and time commitment in working towards a reflective and considered practice.

REFERENCES

1. Toth-Cohen S. "Using cultural-historical activity to study clinical reasoning in context". Department of Occupational Therapy Faculty Papers. Paper 7. 2008. <http://jdc.jefferson.edu/otfp/7> (20 June 2014). [ Links ]

2. Cutchin MP Aldrich RM, Bailliard AL, Coppola S. Action theories for occupational science: The contributions of Dewey and Bourdieu. Journal of Occupational Science, 2008; 15:157-164. [ Links ]

3. Illich I. A celebration of awareness: A call for institutional revolution. New York: Doubleday, 1970. [ Links ]

4. Duncan EM. "Our bit in the Calabash." Thoughts on Occupational Therapy transformation in South Africa. The 18th Vona du Toit Memorial Lecture. The South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1999; 29 (2): 3-9. [ Links ]

5. Joubert RW. Exploring the history of Occupational Therapy's development in South Africa to reveal the flaws in our knowledge base. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2010; 40 (3): 21 -26. [ Links ]

6. Gray JM. Putting occupation into practice: Occupation as ends, occupation as means. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1998; 52: 354-364. [ Links ]

7. UNAIDS. "Report on Global AIDS Epidemic 2010 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS". 2010. <http://www.unaids.org/documents/20 l0ll23_GlobalReport_em.pdf> (12 June 2012. [ Links ])

8. Richter L, Manegold J, Pather R. Family and community interventions for children affected by AIDS. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council, 2004. [ Links ]

9. McKeller-Basset M, Esterhuizen L, Gray E, Westerman K, Ramugondo EL. The activity and participation restrictions of adolescents on highly active antiretroviral treatment. Unpublished undergraduate thesis: University of Cape Town, 2012. [ Links ]

10. Ramugondo EL. Play and playfulness: Children living with HIV/AIDS. In Transformation through Occupation: Human Occupation in Context. Edited by Watson R, Swartz L. Whurr Published: London, 2004: 171 - 185. [ Links ]

11. Stake RE. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1995. [ Links ]

12. Stake, R. E. Case Studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research second edition. Edited by Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 2000:134-164. [ Links ]

13. Stake RE. Case Studies. In Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry (2nd Ed). Edited by Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. (Eds). London: Sage, 2003:134-164. [ Links ]

14. Stake RE. Multiple Case Study Analysis. New York: Guilford Press, 2006. [ Links ]

15. Reason P Doing Co-operative Inquiry. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Methods. Edited by Smith J. London: Sage Publications, 2003 a. [ Links ]

16. Foot KA. Cultural-Historical Activity Theory: Exploring a Theory to Inform Practice and Research. Journal of Human Behavior in Social Environments, 2014; 24(3): 329-347, DOI: 10.1080/10911359.2013.831011 [ Links ]

17. Leontiev AN. Activity, consciousness, and personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978. [ Links ]

18. Leontiev, AN. Problems of the Development of the Mind. (Trans.M. Kopylova). Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1981. [ Links ]

19. Pierce D. Untangling occupation and activity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2001; 55:138-146. [ Links ]

20. Daniels H. Vygotsky and pedagogy. Routledge/Falmer: London, New York, 2001. [ Links ]

21. Leontiev AN. The problem of activity in psychology. Soviet Psychology, 1974; 13 (2): 4-33. [ Links ]

22. Engestrõm Y Learning by expanding an activity -theoretic approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit Oy, 1987. [ Links ]

23. Engeström Y. Developmental work research as educational research: Looking ten years back and into the zone of proximal development. Nordisk Pedagogik: Journal of Nordic Educational Research, 1996a; 16: 131-143. [ Links ]

24. Engeström Y. Expansive Learning at Work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 2001; 14 (1): 133-156. [ Links ]

25. Erasmus Z. Re-imagining coloured identities in post-apartheid South Africa. In Coloured by history Shaped by Place: New perspectives on Coloured identities in Cape Town. Edited by Erasmus J. Cape Town: Kwela Books, 2001b. [ Links ]

26. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1991. [ Links ]

27. Cooper L. Towards a theory of pedagogy, learning and knowledge in a trade union context: A case study of a South African trade union, unpublished PhD thesis, School of Education, Faculty of Humanities, University of Cape Town, 2005. [ Links ]

28. Hodges D. Participation as dis-identification with/in a community of practice. Mind, Culture and Activity, 1998; 5(4): 272-290. [ Links ]

29. Hodkinson H, Hodkinson, P Rescuing communities of practice from accusations of idealism: A case study of workplace learning for secondary school teachers in England. Paper presented at Experiential: Community: Work-based: Researching learning outside the academy conference. Glasgow University, 2003. [ Links ]

30. McMillan J. Through an Activity Theory Lens: Conceptualizing service learning as 'boundary work. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 2009; (2): 39-60. [ Links ]

31. Pollard N, Sakellariou D, Kronenberg F A Political Practice of Occupational Therapy. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone, 2008. [ Links ]

32. Ramugondo EL, Kronenberg F. Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: Bridging individual collective dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science, Special Issues: Collective and Evolutionary Perspectives on Occupation, 2015; 22 (1): 3-16. [ Links ]

33. Rushford N, Veitch C, Harley K. Collaborative Occupation and Transformation: A Theory Grounded in Experiences of Disaster. Presentation at WFOT 16th congress, Yokohama Japan, 2014. [ Links ]

34. Engeström Y Perspectives on Activity Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [ Links ]

35. Adams F Casteleijn D. New insights in collective participation: A South African perspective. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2014; 44(1): 81-87. [ Links ]

36. Hardman J. Activity theory as a potential framework for technology research in an unequal terrain. South African Journal of Higher Education, 2005; 19(2): 258-265. [ Links ]

37. Engeström Y Innovative learning in work teams: Analyzing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Perspectives on activity theory. Edited by Engeström Y, Miettinen R, Punamäki RL. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1999d: 377-406. [ Links ]

38. Engeström Y Developmental studies of work as a test bench of activity theory: the case of primary care medical practice. In Understanding Practice: Perspectives on Activity and Context. Edited by Chaiklin S, Lave J. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993: 64-103. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Pam Gretschel

Pam.gretschel@uct.ac.za

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The occupational therapist co-researchers are thanked for their willingness and time commitment in working towards a reflective and considered practice.