Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.45 n.1 Pretoria Jan./Apr. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45no1a4

SECTION I

Can post-apartheid South Africa be enabled to humanise and heal itself?

Frank KronenbergI; Harsha KathardII; Debbie Laliberte RudmanIII; Elelwani L RamugondoIV

IBSc OT (Zuyd University), BA Education (De Kempel) International guest lecturer in Occupational Therapy, PhD candidate, University of Cape Town, Director Shades of Black Works

IIB Speech and Hearing Therapy (UDW), M Path (UDW), DEd (UDW) Assoc Prof, Division of Health and Rehabiliation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town

IIIPhD Associate Professor, School of Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science, Graduate programme in Health and Rehabiliation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Western Ontario Canada

IVBSc OT (UCT), MSc OT (UCT), PhD (UCT) Associate Professor, Division of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

This paper posits that for occupational therapy and occupational science to be able to address complex social issues, a radical reconfiguration of the dominant historical rationalities that govern their theorising and practices is required. This position is informed by the rationale for and the philosophical and theoretical foundations of a doctoral study currently being undertaken by the first author, entitled: 'Humanity affirmations and enactments in post-apartheid South Africa: A phronetic case study of human occupation and health'.

The paper commences with the description of the problem - a historicised dual occupational diagnosis. The first diagnosis considers post-apartheid South Africa (1994-2014) as embodying and embedded in a vicious cycle; 'divided-wounded-violent', and held hostage by an enduring history of dehumanisation. The second diagnosis considers occupational therapy and occupational science, which the paper argues are not yet adequately positioned and prepared, both theoretically and practically, to serve as enabling resources for society to interrupt vicious cycles of dehumanisation.

In order to address the problem we need practical knowledge to possibly enable our society to humanise and heal itself. This paper proposes an alternative two pronged philosophical foundation - Phronesis and Ubuntu - to advance such knowledge. The synergistic use of critical contemporary interpretations of Aristotle's intellectual virtue Phronesis (practical knowledge) to guide theorising about knowledge production; along with the African philosophy of critical humanism called Ubuntu to guide theorising about the core concepts of human occupation and health as well as their interrelationship.

Key words: Critical, Phronesis, Ubuntu, human occupation, health, humanity

"What we expect of Africa as it sets out on its regeneration, cannot be divorced from the global environment in which the continent operates. But as Seme, Luthuli and Biko argued, Africa has a responsibility to itself and to the world to contribute its own unique attributes, to offer 'the great gift' of'a more human face"1.

Joel Netshitenzhe, 2013

INTRODUCTION

See Note 1.

South African political strategist Netshitenzhe (2013), speaking about the regeneration of Africa, acknowledges the responsibility which the continent has both to itself and the world for sharing its unique perspectives on what it means to be human.1 As occupational therapists and occupational scientists we are mandated to position and prepare ourselves to respond to the key-challenges of our post-apartheid society and in so doing, contribute to the epistemologies (see Guajardo, Kronenberg and Ramugondo in this Edition) of the profession locally and internationally.

In this paper, South African society is presented as a case example for re-theorising human occupation, health and their inter-relatedness.

It is argued that humanity affirmations and enactments in postapartheid South Africa, concepts which will be discussed later, have occupational and health dimensions that are worth studying in order to align theorising and practice with the need for humanising society. We propose that the regeneration of humanity is possible through human occupation, assuming that if humans have the capacity to dehumanise one another, they can also commit to do the opposite, that is, (re)humanise one another. Pushed by the hugely problematic and complex challenges at hand in contemporary societies both in South Africa and elsewhere, the authors believe that it is fundamental to make visible and matter the processes through which pervasive dehumanisation dynamics can be defeated on a day-to-day basis through human occupation, generating practical knowledge to possibly enable society to humanise and heal itself.

Although rarely brought to the fore, this is not a new premise. In 1972 the American psychiatrist Bockoven asserted that "occupational therapy has a message that can be more effectively utilized if it is not limited to being a service solely for sick people"2:219. He also claimed occupational therapy to be "a neglected source of community re-humanisation"2:217, and that "occupational therapists could and should assume effective leadership roles in humanizing [American] occupational life by emancipating it from standardisation and conformity"2:222. Bockhoven nudged the profession to provide leadership in social change. More recently Laliberte Rudman coined the term 'occupational imagination', arguing for a transformative approach to scholarship which would require the fostering of "a radical sensibility to challenge scholars to make critical, creative connections between the personal, occupational 'troubles' of individuals and public 'issues' related to historical and social forces"3:1. This article provides a theoretical rationale for doing just this. As such it is positioned on what may be framed as 'the moving line' between the profession of occupational therapy and the discipline of occupational science. What remains uncontentious within the debate is that occupational therapy and occupational science both ontologically view humans as occupational beings and share human occupation as a core concept. The former always in relation to health and the latter including and going beyond its relationship with health4.

BACKGROUND TO THE PAPER

This paper is based on the proposal of the first author's doctoral study which asks: How does humanity become affirmed and enacted in everyday life in post-apartheid South Africa? It does not report on the study's methodology or findings. Instead, it seeks to stimulate thought and discussion by elaborating on the rationale as well as philosophical and theoretical foundation of the proposed doctoral research. The rationale of the study is informed by a historicised 'dual occupational diagnosis': firstly, how are we doing together in/ as post-apartheid South Africa? And secondly, how are occupational therapy and occupational science doing as a resource in response to the first diagnosis? The study is grounded in Critical contemporary interpretations of Phronesis (practical wisdom), one of Aristotle's three intellectual virtues-to guide theorising about knowledge construction; and Ubuntu, as an African philosophy of Critical hu-manism-to guide theorising about human occupation and health as well as their interrelationship. This two-pronged philosophical foundation provides the conceptual lenses through which data will be analysed and the research questions answered. Our intention in presenting a philosophical paper which underpins the research is to raise awareness of the need to re-theorise human occupation to better position and prepare ourselves in response to the societal challenges at hand.

SITUATING THE PRINCIPAL AUTHOR*

Before elaborating on the doctoral study's 'formal' rationale - a 'dual occupational diagnosis', the first author of this article will briefly situate himself as researcher, disclosing how his personal unfolding life story also importantly contributed to the genesis and shaping of the research topic.

The researcher was born, grew up and obtained his first bachelors degree in pedagogy in the Netherlands (1964-1985). He then travelled extensively and lived in so-called 'developed' and 'developing' societies around the world, gaining work experiences in education, health and social care programs and projects (19841995). These diverse first hand exposures to and engagements in and with the world ignited within him an unerasable and much appreciated [emphasis added by researcher] political consciousness about the nature of human beings and our human condition. He found that "whilst seemingly waging war against itself and the planet, humanity struggles on to keep alive that which makes us human' and that 'humans cannot do without each other"5:25. What then attracted him to study occupational therapy (1995-1999) was what he perceived as this profession's early 20th Century origins in social activism. The coining of 'occupational apartheid' in his 1999 undergraduate thesis on occupational therapy with 'street children'6,7, appears to have been a catalyst for a number of political (positioned in critical perspectives), personal and professional transformative events: co-founding the movement 'Occupational Therapists without Borders'; authoring the WFOT's first ever position paper8; and co-authoring the first volume of 'Occupational Therapy without Borders'9. Through this book project he met his South African life partner with whom he chose to make South Africa home. And 'home' here means, borrowing from Ronald Suresh Roberts (and the 'human occupation for health' dimension in his words cannot be overlooked): 'there where what you do matters ... and what South Africa is doing matters for everyone in the world'10. The researcher acknowledges that he is not from the context in which his study is carried out and that he may always remain an outsider. However, his personal choice to raise a family here, pushes him as a professional and scholar to learn how he may best contribute to what South Africa needs and is (and perhaps is not yet) doing to become 'a home for all people who live in it, united in our diversity'11.

A DUAL OCCUPATIONAL DIAGNOSIS

The 'dual occupational diagnosis', alluded to earlier, examines two interrelated questions which are explicitly framed within a political occupational perspective of health. In its most basic form, the central question that 'traditional' occupational therapy asks a client is: 'how are you doing?' - being concerned with the relationship between what certain (groups of) individuals are doing (and/or not doing) and their wellbeing in their everyday life contexts. An explicitly political occupational perspective of health, drawing from Aristotle who proposed that politics is about 'being concerned with what is good and bad for Man'12,13, may translate into the question 'how are we doing together?' - being concerned with the relationships between what all people who make up a given community or society are doing (and/or not doing) and their wellbeing in the context of everyday life. A 'dual occupational diagnosis', therefore examines the following questions, firstly: 'How are we doing together in/as post-apartheid South Africa?', and secondly: 'How are we doing [together] as occupational therapists and occupational scientists?' in terms of our positioning and preparedness in response to the first question.

The Societal Human Condition of Post-Apartheid South Africa (1994-2014)

As a point of departure for examining the first question, the researcher drew from the 2011 Diagnostic Overview14 conducted by the South African government's National Planning Commission (NPC). To establish a baseline for the National Development Plan (NDP)15, the NPC sought input from all sectors of society to construct a vision for South Africa 2030 and to identify obstacles standing in the way of realising the vision. In order of priorities, the report lists nine key-challenges: 1) too few South Africans are employed; 2) poor educational outcomes; 3) crumbling infrastructure; 4) spatial patterns marginalise the poor; 5) resource intensive economy; 6) high disease burden; 7) public service performance is uneven; 8) corruption; and, last but not least [emphasis added by authors], 9) South Africa remains a divided society14. The NDP outlines how these challenges are to be addressed by 2030 with its key strategic objectives as 'Eliminating Poverty and Reducing Inequality', 'simply put', and well aligned with a neoliberal political emphasis on economy, by increasing employment and raising per capita income15.

Although the NPC's diagnostic overview and the NDP are important and useful working documents, they insufficiently speak to the political-human-occupation-for-health nature of the first diagnostic question and the focus of the doctoral study (i.e. how are we doing together in/as post-apartheid South Africa?). Also, whilst the researcher recognises that our government was democratically elected and as such 'represents us', it is not us, it does not and cannot embody South African society. The government only exists to serve the people who make up South African society. And the NPC seems to underscore this point: "It is up to all South Africans to play a role in fixing the future"15:1. South Africa refers to all of us who live in, make up this society, and who ought to be able to draw from government and our respective professions and disciplines, as resources in the regeneration process. Thus, can post-apartheid South Africa be enabled to humanise and heal itself?'

Wondering what might be 'missing' in the predominantly neoliberal, macro-economic and political framework of the NDP the researcher tapped into a mix of relevant literature and internet sources16,17,18,19,20 and his own lived experiences in South Africa since 2004. This then informed the following 'approximation' of how we are doing together:

'Some twenty years after the end of apartheid and the beginning of democracy, South Africa remains a deeply divided, wounded and violent society. And what may underlie this apparent vicious cycle, and may in fact hold our society hostage, appears to be a long and enduring history of dehumanisation dynamics, a key-mechanism of power under Colonialism, Apartheid, Neo-colonialism [coloniality]21 and Neoliberal Capitalism'.

'Dehumanisation dynamics' refer to an on-going, seemingly self-perpetuating history of systematic renderings of some people by other people as worth (valuing) less than human, or even being regarded as non-human, through the exercising of asymmetrical relations of power. Relevantly, dehumanisation dynamics strongly resonate with the underlying rationale and the proposed working definition of occupational apartheid:

"...the segregation of groups of people through the restriction or denial of access to dignified and meaningful participation in occupations of daily life on the basis of race, colour, disability, national origin, age, gender, sexual preference, religion, political beliefs, status in society, or other characteristics. Occasioned by political forces, its systematic and pervasive social, cultural, and economic consequences jeopardize health and wellbeing as experienced by individuals, communities, and societies"7:76.

The definition of occupational apartheid underscores the need to historicise the proposed 'dual occupational diagnosis', situating it long before Apartheid's institutionalisation, and going back to the beginnings of colonisation on the African continent, which for South Africa 'started' with the arrival and the founding of the Cape Colony in Cape Town by Jan van Riebeeck in 165222.

The following phrases by writers from Africa also resonate with the proposed vicious cycle and its underlying dehumanisation dynamics: 'Africans are seeking to understand and restore their violated humanity'23; "Africans are injured and conquered people24:44; 350 years of patterns of unfree black labour in South Africa25,26; "Fifty years after the celebration of decolonisation the 'European game' which denied Africans agency, continues to prevail [...] coloniality remains a reality"27:243. An exhortation from Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, drawing from the African worldview of Ubuntu, resonates directly with the problematic 'dehumanisation dynamics': 'We are humanized or dehumanized in and through our actions toward others . My humanity is caught up, bound up, inextricably, with yours. When I dehumanize you, I inexorably dehumanize myself"28:31. We contend that the inter-related human occupation and health dimensions of these actions are critically important sites of investigation for occupational therapy and occupational science.

Positioning and Preparedness of Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science

The second question asks, to what extent are occupational therapy and occupational science positioned and prepared as a relevant resource to enable this society to humanise and heal itself? Acknowledging that it may not be doing justice to historical nuances, the short answer to this question is that our profession and discipline are not adequately positioned and prepared. However, 'not' may mean 'not yet'. The next section will briefly address both questions arising from the dual occupational diagnosis within an unfolding historical context. Occupational therapy was introduced in South Africa from Britain at the end of the Second World War, in a postcolonial era, with an emerging apartheid government29,30. Joubert's doctoral study problematised this birth as it gave rise to a 'flawed epistemology', because of its origins within a Eurocentric, paternalistic and male dominated health milieu under the influence of the medical model; the unnatural, oppressive nature of governance at the time; and the design of curricula and research was inadequately informed, leaving out disabled people and the diverse majority population of the country31. However valid this critique may still be, the past decade also bears evidence of relevant contributions by South Africans to globally emergent rationalities (ideas and theories) of occupational therapy and occupational science32: two WFOT keynotes33,34; several new concepts: occupational choice35; occupational consciousness36; collective occupations37; Fanonian practices38. And also significant, in 2018 South Africa will be hosting the 17th World Congress of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists, themed 'Connected through Diversity, Positioned for Impact', for the first time ever on the African continent (see Guajardo, Kronenberg & Ramugondo in this Edition).

Box 1 on page 23 depicts the interplay of dominant and emergent (ope)rationalities (rationalities put into practice) evident in contemporary occupational therapy and occupational science literature3,5,32,36,37,39,40,41,42,43.

Box 1 suggests that the dominant rationalities favour individualism, are a-historical and a-critical, embrace modernity and a monocultural worldview, support scientific evidence based practice and subscribe, often inadvertently or unthinkingly44, to neo-liberal market forces (see Guajardo, Kronenberg and Ramugondo paper in this Edition). In contrast, the emergent rationalities evident in the extant literature are more Ubuntu-orientated, adopt a critical-emancipatory stance, appreciate an ecology of views, ideas and ways of knowing, particularly those arising from 'the South' or our society's peripheries (see Guajardo, Kronenberg and Ramugondo in this Edition), support possibilities and practice-based evidence and seek sustain-abilities32 (pun intended). However, the juxtaposition of rationalities in Box 1 is not intended to dichotomise but rather to depict the dynamic interplay between the primary concerns, political positions, worldviews, evidence and ideologies that shape how the profession and the discipline engage with societal issues. When faced with hugely complex realities and challenges such as those identified in the first occupational diagnosis, what is required of occupational therapy and occupational science is to imagine different positionings. Contextual relevance means broadening our horizon of possible (ope)rationalities. Sandra Galheigo's closing keynote at the 2010 WFOT World Congress in Chile provides an example of such an imagining exercise. She opened her lecture with a powerful metaphor - the 'Tale of the Fisherman' (Box 2), to reignite our ethical and political responsibilities as professionals and scholars towards the societies in which we find ourselves.

A man is walking by the riverside when he notices a body floating down stream. A fisherman leaps into the river, pulls the body ashore, gives mouth to mouth resuscitation, saving the man's life. A few minutes later, the same thing happens, then again and again. Eventually yet another body floats by. This time the fisherman competely ignores the drowning man and starts running upstream along the bank. The observer asks the fisherman what on earth he is doing. Why is he not trying to rescue this drowning body? "This time", replies the fisherman, "I'm going upstream to find out who is pushing these poor folks into the water".45,236

Addressing a global audience, Galheigo suggested some of us to be in the position of the fisherman ... and that more of us are called upon to follow his example ... but also that we must collectively become more concerned with the upstream structural conditions that (re)produce downstream challenges46. The first author imagines that above and beyond, we must also position ourselves at the river's origins, that is, if we are to get to and prepare ourselves to address what may indeed be at the root of the seemingly vicious relational cycles of our deeply divided-wounded-violent South Africa.

In summary, we posit that addressing post-apartheid South Africa's deeply troubled human condition requires that we - as a society and as a profession and discipline - must push above and beyond the structural conditions and their consequences - the vicious cycle 'divided-wounded-violent', and get to their origins, the politics of being human, which appears as the root cause of the gross inequalities and subsequent high levels of poverty that post-apartheid South Africa embodies and is embedded in. We therefore need to understand how to affirm and enact humanity on a day-to-day human occupation basis. The doctoral research aims to generate knowledge in this regard, but on what philosophical and theoretical basis? The next section engages this question, again drawing on the doctoral proposal.

PHILOSOPHICAL AND THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Appreciative of the anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod's stance "... that every view is a view from somewhere and every act of speaking, a speaking from somewhere"47:141, the study integrates three 'somewheres'. The inescapably first and foremost political nature of the study's question and dual occupational diagnosis, guided the researcher to ground it in Critical contemporary interpretations of Phronesis and Ubuntu. The terms Critical, Phronesis and Ubuntu are deliberately and consistently capitalised to distinguish them from small case versions, to allow for different positionings, respectively on a continuum of 'political - apolitical somewheres'.

Critical: As Radical Transformative

Being Critical means taking a stand, disclosing upfront, that the focus and underlying rationale of the investigation is to be about a long and pervasive history of unequal relations of power which produced and continue to reproduce structural conditions and consequences that are harmful to humanity (and the planet). Neu-man in this regard points to ". a critical process of inquiry that goes beyond surface illusions to uncover the real structures in the material world in order to help people change the conditions and build a better world for themselves"48:95.

Critical means radical, intervening at the roots, committing to transforming or eliminating anything that harms or conspires against our humanity49,50,51,52, which (may) include rethinking our (dominant) philosophical and theoretical foundation. Taking a Critical position as a researcher requires a going beyond classical and / or traditional discourses of Phronesis and Ubuntu. It meant adopting contemporary, emergent, indeed Critical interpretations of these philosophical categories: Phronesis - to guide theorising about knowledge construction, and Ubuntu - to guide theorising about the core concepts of: human occupation, health and their interrelationship. Diagramme 1 depicts the philosophical and theoretical foundations on which to build a Critical understanding of the politics of being human, an understanding that is essential for interrupting dehumanisation dynamics.

The Critical grounding of the study, temporality and place in which the researcher uses Aristotle's classical conception of Phronesis prompted him to draw from Flyvbjerg's contemporary interpretation of the philosophy; 'to not only involve appreciative judgments in terms of values but also an understanding of the practical political realities of any situation as part of an integrated judgment in terms of power', explicitly raising questions about power and outcomes, such as: "Who gains and who loses? Through what kind of power relations? What possibilities are available to change existing power relations"53:284? This then also pushes us to challenge for example; whose conceptions of knowledge and their constructions may count more than others, which is powerfully problematised by Boaventura de Sousa Santos in his recent book 'Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemi-cide54,55. Leonhard Praeg's concern with "... the historical conditions for the possibility of knowledge on and from Africa today" 56:56 also implicates such questions of power and its outcomes.

Phronesis: Foregrounding Practical Values and Power Rationality

Aristotle identified three intellectual virtues: episteme-scientific, theoretical knowledge; techne-technical, applied scientific knowledge; and phronesis-practical knowledge or wisdom. For a juxtaposition of these three kinds of knowledge and their main characteristics, see Box 3 (adapted from Flyvbjerg57). According to Flyvbjerg, Aristotle regarded phronesis as the most important of the three because it is that activity by which the theoretical and practical instrumental rationality of episteme and techne is balanced by value and power rationality.53 Phronesis involves 'the good example' and context-dependent knowledge, guiding practices that are 'good for Man'51.

The nature of the research question does not seem to call for knowledge that is purely scientific or technical. It seeks a different kind of knowledge, drawing from Aristotle to advance "the ability to deliberate rightly"13:1140a24-b12 about which human occupations may promote or prevent harming health. In this scenario, that which people can do to affirm humanity is a variable, given that "... it may be done in different ways or not at all"13:1140a24-b12. Considering that scientific knowledge is invariable "... it is distinguished by its objects, which do not admit of change, these objects are eternal and exist of necessity, e.g. 'the necessary truths of mathematics"13:1139b15-30, it was not considered suitable to answer the study's main question. Technical knowledge was also not suitable because it constitutes production aimed at an end other than itself, a skill used to produce something. Humanity affirmation and 'doing well' cannot be reduced to a technical competence. That then leaves phronesis as the preferred intellectual virtue and philosophical position. In Nich-omachean Ethics, Aristotle argues: "...what remains, then, is that Phronesis, practical knowledge/wisdom, is a true state, reasoned, and capable of action with regard to things that are good or bad for Man...", because it considers "...things which admit of change, e.g. the contingencies of everyday life"13:1140a24-b12.

We started this paper arguing that the regeneration of Africa and South Africa in particular is advanced by drawing on the continent's unique attributes. The next section summarises sections of the research proposal that address Ubuntu as an African philosophy of Critical humanism.

Ubuntu: As an African Philosophy of Critical Humanism

The African philosophy Ubuntu is framed by Leonhard Praeg as Critical humanism [capitalised throughout by researcher], who distinguishes it from traditional Western humanism by comparing their central concerns. Whereas the focus of Western humanism is simply the human - the human capacity for science, beauty and knowledge in a world that no longer defers meaning to a transcendental source - in Critical humanism, the focus is on a more fundamental or primary concern, i.e. "...with the relations of power that systematically exclude certain people from being considered human in the first instance"58:12. This concern strongly resonates with why the first author coined the notion 'occupational apart-heid'6,7. Mogobe B. Ramose relevantly puts this concern in the local context of post-apartheid South Africa, remarking that: "Africans are an injured and conquered people, and this is the pre-eminent starting point of African philosophy in its proper and fundamental signification"59:44. In other words, "...to do African philosophy, to posit, to ask and address the question of Ubuntu is therefore always, inescapably first and foremost, a political question"58:l2.

Tutu tirelessly stressed that dehumanisation causes harm to both the injured and the injurers, noting that '...my concern ... the fact of our being wounded, we are lying, we mislead ourselves, if we pretend that there is anyone who lived under Apartheid who has not been damaged'l9. The American philosopher and feminist theorist Drucilla Cornell defends Ubuntu on two counts: as a new humanism, a new ethical vision of being human together, which appears to speak directly to the heart of this study's dual occupational diagnosis, calling for a thoroughgoing philosophical, political and ethical critique of racist Western modernity. And, secondly, because it offers us "...a way of renewing and reinvigorating the philosophical and political project of human solidarity and, if one takes 'revolutionary Ubuntu' seriously, radical transformation"60:170, which is in line with this study's interpretation and grounding in 'Critical' soil.

The researcher finds Van Marle and Cornell's interpretation of Ubuntu particularly relevant and useful for re-imagining and reframing theorising about human occupation, health and their interrelationship in the context of understanding and addressing South Africa's deeply troubled societal human condition:

"Ubuntu in a profound sense, and whatever else it may be, implies an interactive ethic, or an ontic orientation in which who and how we can be as human beings is always being shaped in our interaction with each other. This ethic is not then a simple form of communalism or communitarianism, if one means by those terms the privileging of the community over the individual. For what is at stake here is the process of becoming a person or, more strongly put, how one is given the chance to become a person (a human being, added by researcher) at all. The community is not something 'outside', some static entity that stands against individuals. The community is only as it is continuously brought into being by those who 'make it up', a phrase we use deliberately. The community, then, is always being formed through an ethic of being with others, and this ethic is in turn evaluated by how it empowers people"61:206.

In summary, Critical contemporary interpretations of European and African thought are brought together by adopting ('planting') both Phronesis and Ubuntu as the philosophical pillars ('seeds') for radically ('grounded in Critical soil') reconfiguring theorising and practices in occupational therapy and occupational science (also see Diagram 1).

The next section will propose subsequently reframed interpretations of human occupation and health and their interrelationship that infuse both our profession and discipline.

Repositioning and Re-framing Human Occupation, Health and Their Interrelationship

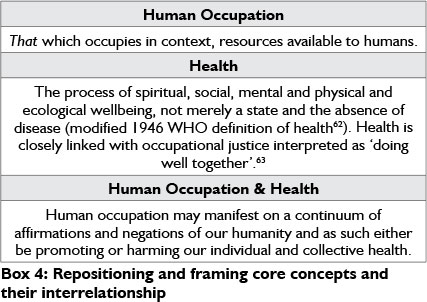

We have proposed the need for changes in the philosophical discourses and theoretical foundations of occupational therapy and occupational science to better position and prepare us for possibly addressing complex social issues in general, and the humanisation of everyday life in particular. Perhaps such changes are (metaphorically) analogous to a manipulation of the 'DNA structure' of occupational therapy and occupational science. If we can agree that all subjects and practices are shaped within particular discursive contexts, then the proposed Critical contemporary interpretations of Phronesis and Ubuntu consequently call for a shift in positioning and framing of the core concepts of human occupation and health as well as their reciprocal relationship. Box 4 identifies ways of repositioning and framing core concepts and their inter-relationship which often times may either be overlooked or taken for granted.

Human Occupation

What appears to constitute a shift in theorising about human occupation is a repositioning of 'humans who occupy', the traditional dominant discourse, to foregrounding 'humans who are occupied'. The notion of 'that' which occupies, refers to what humans do and do not do every day, which is done with (resources) and to (having implications for) ourselves and others (and the environment), and this can to some extent be observed. That also refers to a complex schema of (possibly unquestioned) beliefs, values, rationalities that shape our (more or less conscious) intentionalities, which cannot be directly observed. Human occupation is always both embodied (person, agency) and embedded (context, structure). For analytical purposes, depending on (concrete) historical conditions, possibilities of human occupation manifest on continuums, for example; doing-not doing; ordinary-extraordinary; political-apolitical, meaningful-meaningless, social-asocial, historic-ahistoric; constructive-destructive; intentional-unintentional; health promoting-harming health; nonviolent-violent; etcetera.

The notion 'resources' can constitute means and opportunities, and may be both internal and external, individual and collective, private and public, material (land, housing, water, jobs, money, institutional, etc.) and immaterial (spiritual, relationships, intellectual, knowledge, capabilities, time, etc.). The notion 'available': resources may exist, but are not considered as available to some people for person and/or context related (endogenous and/or exogenous) reasons. For example, access to education is guaranteed by the Constitution, but it may not be accessible. Or although, access to resources is guaranteed, internalised inferiority may not allow a person to regard the resource available due to fearing not being able to successfully make use of it. The notion 'humans': literally speaking, since 31 October 2011, our planet now hosts more than 7 billion of us64, occupational beings. The fact that this statistic could be arrived at implies a set of common characteristics that allow humans to be identified and counted as such. However, a critical look at human history reveals that some humans count (matter as being) more human than others, that is, the notion 'humans' constitutes a matter of 'the politics of being human'.

Health

The framing of health in Box 4 appreciates the common principles under the term social medicine. Resonating with perspectives falling within a social determinants of health framework, there is recognition of the profound impact of social and economic conditions on health, disease, and the practice of medicine; a view of population health as a social concern; and a societal role for the promotion of health via individual and social means65. Health and disease are viewed dialectically and dialogically, and healthcare is understood as part of a historical and social process. It assumes that any discussion about health today is inevitably a social, international and political discussion66.

The Human Occupation-Health Interrelationship

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, the Kenyan literary and social activist, powerfully speaks to the proposed discourse, 'the politics of being human', and the Ubuntu guided reframed premise of the dialectical and dialogical dynamic between human occupation and health:

"Our lives are a battlefield on which is fought a continuous war between the forces that are pledged to confirm our humanity and those determined to dismantle it; those who strive to build a protective wall around it, and those who wish to pull it down; those who seek to mould it and those committed to breaking it up; those who aim to open our eyes, to make us see the light and look to tomorrow (...) and those who wish to lull us into closing our eyes"67:50.

Alex Boraine and Janet Levy edited a book in 1994 titled 'The Healing of A Nation?'68 The inclusion of a question mark back then still applies twenty years onward, to acknowledge that there exists "...no quick fix, no magic formulae (...) which will remedy the sickness that reached endemic proportions leaving many victims in its wake'68:XIV. Whereas Boraine and Levy primarily framed 'the sickness' as the legacy of apartheid (1948-1994), this study contex-tualised the post-apartheid human condition of South Africa within a much longer history of enduring dehumanisation dynamics. Back in 1995, Boraine suggested that "...the healing of the nation will require an absolute commitment to both economic justice and the restoration of the moral order"68:XIV. The phrase 'the restoration of the moral order' is problematic because it assumes the pre-existence of such an order, which cannot be claimed at least since the beginnings of colonialism. Whereas the NDP prioritises a commitment to address economic challenges, we recommend commitment, at least by the profession and the discipline, to the second goal, albeit reframed as 'the restoration of our humanity'. If humans have the capacity to dehumanise one another, they can also commit to do the opposite, that is, (re)humanise one another... commit to learning how to humanise everyday life.

WAY FORWARD

This paper used the rationale and philosophical-theoretical foundations of the first author's doctoral proposal as the basis for its argument that occupational therapy and occupational science can become catalysts for creating a society with 'a more human face'. To date, there is no literature or empirically verified methods to confirm this argument. To do so would require substantial repositioning and re-framing of human occupation, health and their interrelationship. The following set of value and power rationality questions (adapted from Flyvbjerg53,57) are part of the researcher's ongoing interrogation of data and these may enable us to better position and prepare ourselves to generate (more) contextually relevant practical understandings in relation to the challenges at hand: What are we doing with the resources available to us?; Who decides what we are doing and what resources are available to us and by what mechanisms of power?; How does what we are doing manifest on the continuum affirming/negating humanity - promoting/ harming health?; What should we be doing about it?

REFERENCES

1. Netshitenzhe, J. Inaugural Pixley ka Isaka Seme Lecture:The vision of Seme 107 years on: Is civilization still a dream and is the regeneration of Africa possible', Columbia University, New York, 2013. [ Links ]

2. Bockoven, J. S. (1972) Occupational Therapy: A Neglected Source of Community Rehumanization. In: J. Sanbourne Bockoven. Moral Treatment in Community Mental Health. Springer, New York: 217-228. [ Links ]

3. Laliberte Rudman, D. Embracing and Enacting an 'Occupational Imagination': Occupational Science as Transformative. Journal of Occupational Science. DOI: 10.1080/14427591.2014.888970. To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2014.888970. 2014. [ Links ]

4. Molineux, M. & Whiteford, G. Occupational science, Genesis, evolution and future contribution. In Duncan, E.A.S. (Ed), Foundations for practice in occupational therapy. Edinburgh: Elsevier. 2011: 243-253. [ Links ]

5. Kronenberg, FF Doing Well-Doing Right Together: A practical wisdom approach to making occupational therapy matter. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy.2013; 60(l): 24-32. [ Links ]

6. Kronenberg, FF Street Children: Doing Being Becoming. Unpublished occupational therapy thesis. Zuyd Unversity, Heerlen. 1999. [ Links ]

7. Kronenberg, F Pollard, N. Overcoming occupational apartheid: A preliminary exploration of the political nature of occupational therapy. In: F. Kronenberg, S. Simo Algado, N. Pollard. (Eds.) Occupational Therapy without Borders: Learning from the Spirit of Survivors. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone-Elsevier, 2011. [ Links ]

8. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Position paper on Community-Based Rehabilitation. https://www.wfot.org/office_files/CBRposition%20Final%20CM2004%282%29.pdf. 2004 [ Links ]

9. Kronenberg F, Simo Algado S, Pollard N. Occupational Therapy without Borders: Learning from the Spirit of Survivors. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone-Elsevier. 2004. [ Links ]

10. Matabane, K. Conversations on a Sunday afternoon. Johannesburg. Matabane Filmworks. www.variety.com/review/VE1117928534/?refcatid=31. 2005 [ Links ]

11. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/1996/a108-96.pdf. 1996. [ Links ]

12. Berry, CJ (1986). Human nature: Issues in political theory. MacMilan, London. Ethics, second edition, translated by Terence Irwin, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1999. [ Links ]

13. Aristotle The Nicomachean Ethics (abbreviated as N.E.), translated by J. A. K. Thomson, revised with notes and appendices by H. Tredennick, Introduction and Bibliography by J. Barnes. Harmond-sworth, Penguin, 1976. [ Links ]

14. National Planning Commission. Diagnostic Overview. http://www.npconline.co.za?MediaLib/Downloads/Home/Tabs/Diagnostic//Diagnostic%20Overview.pdf. 2011. [ Links ]

15. National Planning Commission. National Development Plan. http://www.npconline.co.za/MedicalLib/Downloads/Downloads/NDP%202030%20-%20Our%20future%20-%20make%20it%20work.pdf. 2011. [ Links ]

16. Adu-Pipim Boaduo. N. The Rainbow Nation: Conscience and Self Adjudication for Social Justice, Governance and Development in the New South Africa. The Journal of Pan African Studies. 2010; 3(6) Pg nos. [ Links ]

17. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Why does South Africa have such high rates of violent crime? Supplement to the final report of the study on the violent nature of crime in South Africa. http://www.csvr.org.za/docs/study/7.unique_about_SA.pdf. 2009. [ Links ]

18. Ramphele, M. A Discussion with Dr. Mamphela Ramphele. The Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. Retrieved 25 April 2012, at: http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/interviews/a-discussion-with-dr-mamphela-ramphele. 2012. [ Links ]

19. Tutu, D. Time for 'haves' to help rebuild SA. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/time-for-haves-to-help-rebuild-sa-1.1121343. 2011. [ Links ]

20. Tutu, D., Haffajee, Pityana, Lategan, B. A Moral Imperative to Speak: What Does Civic Responsibility Mean in Our Troubled Times? Public debate on civic responsibility at UCT. Wednesday, 24 August 2011. [ Links ]

21. Maldonado-Torres, N. On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural studies.2007; 21 (2-3), March/May: 240-270. [ Links ]

22. South African History Online. http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/arrival-jan-van-riebeeck-cape-6-april-1652. [ Links ]

23. Adesanmi, P You're not a country, Africa - A personal history of the African present. Johannesburg: Penguin Global, 2001. [ Links ]

24. Ramose, M.B. African philosophy through Ubuntu. Harare: Mond Press. 1999. [ Links ]

25. Terreblanche, S. The history of inequality in South Africa: 1652-2002. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. 2002. [ Links ]

26. Terreblanche, S. Transformation: South Africa's Search for a New Future since l986. Johannesburg: KMM Review Publishing Company. 2012. [ Links ]

27. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. Eurocentrism, coloniality and the myths of decolonization of Africa. The Thinker. Pp 34-40. 2013. [ Links ]

28. Tutu, Desmond. No Future without Forgiveness. Doubleday, New York. 1999. [ Links ]

29. Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa. Short History of OTASA. http://www.otasa.org.za/about/history.html. Compiled by Joan Davy - Historian of the Association. March 2003. [ Links ]

30. Duncan, M. "Our bit in the calabash": thoughts on Occupational Therapy transformation in South Africa. 1999. Published in SAJOT ?year page nos [ Links ]

31. Joubert, R. Exploring the history of Occupational Therapy's development in South Africa to reveal the flaws in our knowledge base. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 40(3): 21-26. [ Links ]

32. Kronenberg F Pollard N, Ramugondo EL. Introduction: Courage to dance politics. In: Kronenberg F Pollard N, Sakellariou D, editors. Occupational Therapies without Borders-Volume 2: Towards an Ecology of Occupation-Based Practices. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone-Elsevier, 2011: 376-375. [ Links ]

33. Ramukumba, A. Living in two worlds. Keynote 13th World Congress World Federation of Occupational Therapists, Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. Unpublished? [ Links ]

34. Watson, R.M. Being before doing: The cultural identity (essence) of occupational therapy. Keynote 13th world congress World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Sydney 2006. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 53: 151-158 DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00598.x 2006. [ Links ]

35. Galvaan, R. The Contextually situated nature of occupational choice: Marginalised young adolescents' experiences in South Africa. DOI: 10.1080/14427591.2014.912124 May 2014. [ Links ]

36. Ramugondo EL. Intergenerational Play within Family: The Case for Occupational Consciousness. Journal of Occupational Science. 2012; iFirst:1-15. [ Links ]

37. Ramugondo EL, Kronenberg F. Explaining Collective Occupations from a Human Relations Perspective: Bridging the Individual-Collective Dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science. DOI:10.1080/14427591.2013.781920 To link to this article: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.781920. 2013. [ Links ]

38. Christopher, C. Fanonian practices: Its implications for OT practice in contemporary South Africa. Robin Joubert's Farewell Colloquium. 2013. Unpublished. [ Links ]

39. Magalhaes, L. (2012). What would Paulo Friere think of occupational science? In G.L. Whiteford & C. Hocking (eds). Occupational science: Society, inclusion and participation. West Sussex, UK: Black-well Publishing: 8-19. [ Links ]

40. Hocking, C. Occupations through the looking glass: Reflecting on occupational scientists' ontological assumptions. In G.L. Whiteford & C. Hocking (eds). Occupational science: Society, inclusion and participation. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing,2012: 54-66. [ Links ]

41. Guajardo, A, Simo Algado, S. Una terapia ocupacional basada en los derechos humanos. TOG (A Coruna) [revista en Internet]. 2010 [2 February 2015]. Available: http://www.revistatog.com/num12/pdfs/maestros.pdf. [ Links ]

42. Hammell, K.W. Resisting theoretical imperialism in the disciplines of occupational science and occupational therapy. British Journal of OT. 2011; 74: 27-33. [ Links ]

43. Kantartzis, S, Molineux, M. The influence of western society's construction of a healthy daily life on the conceptualisation of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science. 2011; 18(1): 62-80. 2011. [ Links ]

44. Laliberte Rudman, D. Enacting the critical potential of occupational science: Problematizing the individualizing of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science.2013; 20(4): 298-313. [ Links ]

45. Cohen, S. Visions of Social Control: Crime, Punishment and Classification. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1985. [ Links ]

46. Galheigo S. What needs to be done? Occupational therapy responsibilities and challenges regarding human rights. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2011; 58:60-66. [ Links ]

47. Abu-Lughod, L. Writing against culture. In: R. Fox. (Ed.) Recapturing anthropology: working in the present. Santa Fe: University of Washington Press, 1991. [ Links ]

48. Neuman, W. L. Basics of social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston. Pearson Education, 2004. [ Links ]

49. Giralico, J. Del humanismo radical del humanismo critico. Revista de Filosofia y Socio Politica de la Educacion. Nr 4, 2nd year, 2006:31-36. [ Links ]

50. Dussel, E. Ética de la liberación en la edad de la globalización y de la exclusion. Espana. Editorial Trotta. 1998. [ Links ]

51. Dussel, E. Hacia una filosofia política critica. Espana. Editorial Desclée de Brouwer. 2001. [ Links ]

52. Freire, P Pedagogia del Oprimido. México. Ediciones Siglo XXI. 1996. [ Links ]

53. Flyvbjerg, B. Phronetic Planning Research: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections. Planning Theory and Practice. 2004; 5(3): 283-306. [ Links ]

54. Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Boulder: CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2014. [ Links ]

55. Comaroff, J., Comaroff, J.L. Theory from the South or, How Euro-America Is Evolving toward Africa. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2012. [ Links ]

56. Praeg, L. African studies, epistemic shifts and the politics of knowledge production. In: T. Nhlapo, H. Garuba. African Studies in the Post Colonial University. Celebrating Africa Series. University of Cape Town, Cape Town, 2012:55-64. [ Links ]

57. Flyvbjerg B. Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How It Can Succeed Again. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

58. Praeg. L. A. Report on Ubuntu. Thinking Africa Series. Durban: UKZN Press, 2014. [ Links ]

59. Ramose, M.B. African philosophy through Ubuntu. Harare: Mond Press, 1999. [ Links ]

60. Cornell, D. Ubuntu and subaltern legality. In: L. Praeg, S. Magadla (Eds), Ubuntu: Curating the archive. Thinking Africa Series. Durban: UKZN Press. 2014:167-175. [ Links ]

61. Van Marle, K., & Cornell, D. H. Exploring ubuntu: Tentative reflections. African Human Rights Law Journal. 2005; 5(2): 195-220. [ Links ]

62. World Health Organization. Definition of Health. 1946. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946. http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html. [ Links ]

63. Kronenberg, F. Ubuntourism: Engaging divided people in postapartheid South Africa. In: F. Kronenberg, N. Pollard & D. Sakellariou. Occupational Therapies without Borders: Towards an ecology of occupation-based practices. Oxford: Elsevier, 2011: 195 - 207. [ Links ]

64. United Nations. World to welcome seven billionth citizen. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/world-to-welcome-seven-billionth-citizen.html. New York. 31 October 2011. [ Links ]

65. Anderson, M.R, Smith, L., Sidel, V.W. What is Social Medicine? http://monthlyreview.org/2005/01/01/what-is-social-medicine/MonthlyRe-view. 2005; 56(8)Volume. [ Links ]

66. Moi, J. Surgimiento de la medicina social. http://es.slideshare.net/JoseMoi/medicina-social. [ Links ]

67. Wa Thiong'o. N. Devil on the Cross. Oxford: Heinemann, 1987. [ Links ]

68. Boraine, A., Levy, J.(Eds.). The healing of a nation? Justice in transition. Cape Town. 1995. Publishers? [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Frank Kronenberg

frank.kronenberg@gmail.com

Note 1 : This paper is principally based on the first author's doctoral study under construction, in the text most often referred to as the researcher. The three co-authors are his supervisors and they are included to recognise their influence on how he shaped the rationale and philosophical and theoretical foundations of his research. When 'we' is used in the text, it refers to their collective voice.