Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.44 no.3 Pretoria dic. 2014

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

A study to explore the occupational adaptation of adults with MDR-TB who undergo long-term hospitalisation

Nousheena FirfireyI; Lucia Hess-AprilII

IBSc OT (UWC ), MSc OT (UWC) Assistant Director: Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Department of Health, Western Cape Gov

IIBSc OT (UWC), MPH (UWC), Post Graduate Diploma in Disability studies (UCT) Lecturer Department of Occupational Therapy University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

The management of multi drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is a lengthy process that involves medical treatment for a period of at least 18-24 months that includes compulsory hospitalisation for a period of at least six months. MDR-TB is, however, associated with poor treatment outcomes in South Africa. Although Occupational therapy's philosophy focusses on the use of occupation to promote health and well-being, the occupational engagement and adaptation of patients hospitalised for MDR-TB have never been explored. This article reports on a qualitative study that was aimed at exploring the occupational adaptation of adults with MDR-TB while undergoing long-term hospitalisation at a hospital in the Western Cape. An exploratory and descriptive research design employing an interpretive research approach was utilised in the study. Data collection methods included participant diaries, semi-structured interviews, participant observation and a focus group discussion. All data were analysed through thematic analysis. The findings highlighted several occupational adaptation strategies adopted by the participants while hospitalised. Certain environmental demands were, however, perceived as infringing upon their occupational choices and influencing their occupational identity and competence. It was recommended that the hospital adopt an occupational therapy programme that focusses on occupational enrichment to facilitate occupational adaptation.

Key words: MDR-TB, long-term hospitalisation, Occupation, Occupational Adaptation, Occupational enrichment

INTRODUCTION

Over the last few years MDR-TB emerged as a serious concern in South Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO)1 estimates that a total of 14 000 MDR-TB cases arise in South Africa annually. This is confirmed by the Department of Health2 which indicates that over the period of January 2004 to April 2007 there were over 16 000 MDR-TB cases across all of the provinces in South Africa, with the highest burden being in Kwa-Zulu Natal (32%) and the Western Cape (23%).

The management of MDR-TB is a lengthy process with patients required to be on treatment for a period of at least 18 to 24 months2. Prior to 2013 patients with MDR-TB were required to undergo compulsory hospitalisation for a minimum period of six months or until they had a minimum of two consecutive monthly sputum cultures that tested negative3. While the recently developed National Guidelines for Drug Resistant TB4 provides guidance for the management of stable MDR-TB patients closer to their homes in health facilities and in the community, compulsory long term hospitalisation is still required in cases in which complications arise as a result of MDR-TB.

Factors such as poor treatment adherence, poverty and HIV co-infection have all contributed to the escalation of MDR-TB in South Africa5. According to the Department of Health3, the long duration of treatment; requests for discharge from hospital whilst still infectious; discontinuance of treatment due to poor compliance and adverse effects of the medication significantly contributes to the problem of poor treatment outcomes among MDR-TB patients. Other factors that contribute to poor treatment adherence are poor support networks and the stigma attached to the disease6.

It has been suggested by Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF)7 that should treatment adherence improve, treatment outcomes may improve as well. They emphasise that education and the adoption of a client-centred approach are pivotal in ensuring treatment adherence and successful treatment outcomes for TB patients. Likewise, Swartz and Dick6 suggest a move away from the medical model approach to a broader intervention focus that addresses the person's sense of well-being and not just the biological effects of the disease.

Occupational therapy focuses on the use of occupation to promote a person's health and well-being8. Since the introduction of occupational therapy, adaptation has been a key concept within the profession, but was re-introduced in recent years to explain the rationale for practice9,10. According to Wilcock11 engaging in meaningful occupation can provide ways for people to exercise and develop their mental, physical, social and spiritual capacities. Occupational adaptation can also be defined as constructing a positive occupational identity and achieving occupational competence over time in the context of one's environment10. Schkade and Schultz9 based occupational adaptation on the assumption that every individual has a strong internal desire to engage in meaningful occupation with the purpose striving towards competence12.

There are several examples in the occupational therapy literature that supports the notion that occupational adaptation contributes to people's sense of health and well-being following illness or injury13,14,15,16 suggesting that occupational adaptation could be a crucial aspect in addressing health and well-being and by inference, treatment outcomes among patients with MDR-TB. However, while poor treatment outcomes are reported for this population in South Africa, their occupational engagement or adaptation while undergoing long term hospitalisation has not been explored.

In this study, occupational adaptation is understood as the individuals' perceived effectiveness in responding to occupational and environmental demands when adapting to occupational challenges. A person's ability to respond to occupational and environmental demands can be assessed by considering the extent to which they are able to actively sustain a pattern of meaningful occupations and experience a sense of achievement in relation to their goals; as well as a sense of personal satisfaction in relation to their perceived selves.

The aim of this study was therefore to explore how adults with MDR-TB experience and perceive occupational adaptation while undergoing long term hospitalisation. The objectives of the study were to explore how the participants' experience occupational engagement; to explore how they perceive their occupational identity and to explore how they perceive their occupational competence. It was envisaged that the study could inform the development of the occupational therapy service at the hospital.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The theory of Occupational Adaptation was developed by Schkade and Schultz9, who depicted occupational adaptation as how well a person, drawing on their personal abilities, can respond to challenges or demands posed by his/her environment. The theory is based on the assumption that everyone desires to achieve competence or mastery in occupation and that this involves the person adapting to demands from the occupation as well as the environment. The main components in this process are the person (desire for mastery), the occupational environment (demanding mastery) and the interaction between the person and the environment (press for mastery), which elicit an occupational challenge. Occupational adaptation is the process of the interaction between the person and the environment that can be measured by the person's relative mastery and assessed through the person's perceived effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction when adapting to the challenges in producing an occupational response9.

Kielhofner10 introduced adaptation in his Model of Human Occupation, encompassing two components namely occupational identity and occupational competence. Occupational identity refers to a composite definition of the self, which includes one's roles, values, self- concept and personal goals10. Occupational competence refers to the degree to which one sustains a pattern of occupations that reflects one's occupational identity. For occupational adaptation to occur, occupational identity and occupational competence act together to allow individuals to encounter positive experiences. In contrast, inadequate adaptation occurs when a person experiences repeated disorganisation, poor performance and anticipation of future failure10.

Klinger13 as well as Parsons and Stanley14 conducted two separate studies on occupational adaptation from the perspective of people who suffered traumatic brain injury. The findings of Klinger's study indicated that developing a new occupational identity post the brain injury was fundamental to an improvement in the participants' occupational adaptation. Parsons and Stanley14 found that meaningful occupational engagement was essential in the adaptation process of their participants. The findings of both studies highlighted the importance of environmental and social support in achieving and maintaining occupational adaptation.

Based on the literature that associates long-term hospitalisation with institutionalisation and occupational risk factors, it could be argued that patients who undergo long-term hospitalization may be subjected to experiencing difficulties in achieving occupational adaptation17,18'19'20,21. For instance, Bynon et. al.20 assert that despite the fact that hospitals are usually associated with restoration of health, hospitalisation can also have a negative impact on health and well- being while Farnworth and Muhoz21 in describing how occupational deprivation and occupational imbalance affect people who are institutionalised, state that monotonous routines and a lack of occupational choice limit occupational engagement which impacts negatively on individuals' health and well-being. Snowdown, Molden and Dudley17 further state that institutionalisation may lead to patients exhibiting behavioural problems such as aggression associated with enforced idleness, negative staff attitudes, loss of contact with the outside world and the general atmosphere in the institution that hampers self-esteem, decision-making abilities and control over the environment18.

METHODS

Research setting

The setting for this study was a TB hospital in the Western Cape province of South Africa. A multidisciplinary approach is adopted in the hospital programme for MDR-TB patients. The occupational therapy component of the programme includes pre-vocational skills training, life skills groups and recreational and social activities. The purpose of the programme is to provide the patients with opportunities for occupational engagement and to provide structure to their daily routine.

Research design

In this study, the research issues under investigation were the participants' experiences and perceptions of occupational engagement and occupational adaptation while being hospitalised. Therefore, qualitative research with-in an exploratory descriptive research design was utilised. Qualitative research is fundamentally interpretive and based on the subjective experiences, descriptions, opinions, feelings and perspectives of research participants in rich detai122,23. The aim of interpretive research is to understand the subjective experiences of the research participants23. To this end, the interpretive researcher observes the context in which participants' experiences occur and allows them to reflect their world in their own words24

Participant Selection and Recruitment

Four participants were selected to participate in this study through purposive sampling as it allowed for selection based on "the researcher's own knowledge of the population, its elements and the nature of the research aims23166 and assisted the selection of participants according to specific criteria24:

✥ Participants had a medical diagnosis of MDR-TB.

✥ Participants had been hospitalised for a minimum period of 4 months as this would have allowed them sufficient time to experience long-term hospitalisation.

✥ Participants were able to communicate adequately.

✥ Participants were able to keep a diary in which they could choose to record their daily occupations through drawings or written entries.

Potential participants were recruited by a staff member and invited to participate in the study after its purpose and what their participation would entail was explained to them. Table I provides a description of the participants.

Data collection

In this study, diaries, semi-structured interviews, participant observation and a focus group were utilised for the purpose of data collection. Figure 1 on page 20 describes the specific process of data collection used in this study.

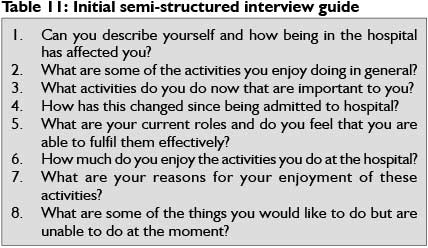

Semi-structured interviews are in-depth interviews conducted with a single research participant and allow for a more natural way of interacting25. Interviews are aimed at determining what participants think, know and feel and more than one interview may be required to gain such an understanding25. An initial interview that lasted approximately 45 minutes was conducted with each participant. Questions posed pertained to participants' perceptions of themselves, their occupational lives while in hospital and the meaning and purpose they attached to their occupations (see Table II for the initial interview guide).

Walliman22 suggest that diaries are useful tools for the collection of information regarding personal interpretations of experiences and feelings that participants may not express publicly, while Jacelon26 states that diary entries can be used to supplement interview data. Towards the end of the initial interview, each participant was provided with a diary and invited to write daily about how they spent their time at the hospital over a period of seven days. All diaries were returned after the seven day period and varied in content from brief reports describing how days were spent to elaborate reflections that described thoughts and emotions in relation to the participants' occupational engagement while in hospital.

Participant observation allows the researcher to become an instrument of observation by witnessing first-hand how people act within a particular setting24. In addition, participant observation allows the researcher an opportunity to gain insight into contexts, relationships, behaviour and information that might otherwise remain unknown27. Participant observation occurred over a period of one week for approximately two hours a day at various intervals. This allowed for the observation of the participants' occupational repertoire as it occurred throughout the day. In addition to field notes, photographs that provided a record of the participants' occupational engagement were taken by the researcher during the observation period.

A follow-up semi structured interview that lasted approximately one hour was conducted with each participant two weeks after the initial interview. The purpose of the follow-up interview was to gain a deeper understanding of the participants' experience of occupation in the hospital environment. The participants' were asked about their occupational needs, goals and future plans; and their perceptions on their occupational competence were explored (see Table III for the follow-up interview guide). All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

The main strength of focus groups is that they allow researchers to distinguish similarities and differences in the participants' opinions and experiences through group interaction28 thereby allowing them to examine different perspectives as they operate within a social network. One focus group that lasted for approximately one hour was facilitated with all the participants. According to Hurworth29 the use of photographs during interviews may lead to more in-depth perspectives as photo elicitation delves deeper into the human consciousness than interviews or focus groups do independently. Accordingly, the photographs that were taken during the period of participant observation were used for the purpose of photo elicitation in the focus group. Each participant was invited to select a photograph and to share his/her thoughts and feelings regarding the occupation it depicted with the rest of the group. The focus group was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was done for each data set i.e. diary entries, field notes and transcripts by following the process of thematic analysis as suggested by Braun and Clarke30. The process involved generating codes from the raw data and refining these into themes by engaging in six phases namely (1) familiarising (transcribing data, reading through transcripts), (2) producing codes, (3) merging similar codes into categories, (4) searching for themes, (5) defining and naming themes and (6) producing the report.

Trustworthiness

Strategies such as credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability were used in order to ensure the trustworthiness of the data24- Credibility was ensured through data source triangulation24, theoretical triangulation31 and member checking23. Semi-structured interviews, diaries, participant observation and a focus group interview are examples of the different data sources utilised. Each additional piece of data strengthened or confirmed previous findings thus strengthening the triangulation of the data. The literature offered multiple perspectives to help explain the data through theoretical triangulation. With regards to member checking an additional focus group was facilitated with all four participants whereby a summary of the findings were reviewed by the participants in order to ensure its accuracy. Transferability was ensured through providing a detailed description of the research process, the participants and the data. A thorough record of the data analysis trail was maintained throughout this study with the purpose of ensuring the confirmability and dependability of the study. In addition, the researcher's personal reflections were recorded in a reflective journal throughout the period of data collection so that these could be explicit and through debriefing sessions with the research supervisor32.

Ethics

To ensure that this study was conducted in an ethical manner, approval for the study was gained from the University of the Western Cape and the medical superintendent of the hospital. The participants were informed about the nature of the study and informed written consent was obtained from them. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants were informed of their right to withdraw their participation at any time without being penalised. Confidentiality was maintained through securing audio-tapes and transcripts in a locked cupboard that only the researcher could access. Anonymity was maintained through ensuring that diaries, field notes, transcripts and photographs did not contain any information that could identify the participants, hospital or staff.

FINDINGS

The aim of this study was to explore how adults with MDR-TB who undergo long-term hospitalisation experience occupational adaptation. Occupational adaptation draws on individuals' occupational identity and occupational competence10 with the three main components influencing the occupational adaptation process being the person, the occupational environment and the interaction between the person and the environment9. Within the context of this study, person refers to the adult with MDR-TB, occupation refers to those occupations they engaged in while hospitalised and environment refers to the hospital where they underwent long-term hospitalisation. The findings highlight the participants' perceptions about the extent to which they were able to actively sustain a pattern of occupations that were meaningful, purposeful and afforded them a sense of personal satisfaction. The adaptation strategies the participants used in managing their occupational engagement and adapting to occupational challenges are described. Table IV provides an outline of the themes and related categories.

Theme 1: Constraints to occupational adaptation

This theme reflects the participants' perceptions of themselves firstly, as human beings and secondly, as occupational beings. The theme is presented in two categories:

A sense of loss due to unmet needs

While having a diagnosis of MDR-TB itself did not necessarily change their views of themselves, the participants stressed that undergoing long-term hospitalisation infringed their basic human needs such as freedom, autonomy and respect, leaving them with a sense of loss that impacted how they felt about themselves. They all felt that the hospital rules and regulations stripped them of their freedom and compared their feelings of being trapped to that of being incarcerated.

... you've been taken out of society and put into a certain place without a cut off period...I mean, that's like taking me, putting me in and locking the door...they mustn't come and lock me up; I mean that is like putting us in prison. (P4)

They expressed that they felt isolated from the outside world as a result of being hospitalised and that this contributed to the lack of meaning and low morale, motivation and drive that they experienced.

....you feel as if you are cut off from the world...that is also part of a person's frustrations... Once you are here, and you start feeling lonely, you basically, you lose interest in the whole world, in life, you know... (P4)

With regards to the need for autonomy, the participants felt that being hospitalised already inhibited them and on top of that they had no voice inside the hospital when it came to expressing their needs and voicing their opinions on issues that affected them.

...if they implement something at the hospital...before they implement something, get the patients together and have a meeting and ask them, "How do you feel about this? Are you satisfied?" (P2)

In terms of the need for respect, the participants expressed the need to be respected as adults and perceived themselves to be stigmatised for having TB as they were disrespected and treated as children by the staff.

While they (patients) are still busy they (staff) say "come, come, come" to the sick patients in the sick bay, hit them. They are not their children, they are grown-ups. (P1)

A lack of occupational choice

In addition to an expressed sense of loss due to their needs for freedom, autonomy and respect not being met, the participants spoke about the loss of occupational choice and how this affected their need for occupational engagement.

You sit and think...If I was working today, on Friday I would get paid, but look where I am sitting now. And Friday nights I think, yes, I would have been at a club, dancing, but look where I am sitting now (P2).

They indicated that they experienced a sense of loss of their occupational roles. For instance, they felt that they were unable to choose occupations to fulfil their roles as parents or caregiv-ers and missed out on valuable opportunities to engage with their families.

He is my child.I am still his mother. I brought him into this world and I must look after him. You miss out on everything, creche concerts, everything, I miss out on everything... (PI)

One participant likened his experience to that of a bird with broken wings trapped in a cage. Like a bird in a cage that is not able to fly, so too the participants were unable to function as they did prior to their hospitalisation, leaving them with a void in their lives.

It's like a bird, cut his wings and throw him into a cage and he can't fly anymore like he used to. (P4)

They felt angry and frustrated at times, specifically with regards to their inability to have control over their occupational choices, which resulted in them engaging in monotonous routines and finding little or no meaning in their occupational engagement.

We do the same routine, get up in the morning, take tablets, have breakfast, wash, brush your teeth ... sometimes I read my bible or sit by the window and look at the sky. (P3)

One participant expressed that he preferred to participate in activities that he enjoyed doing but as he was restricted in his choice of occupation it lead to boredom.

Sometimes you just want to go out...and walk to the beach... It bores you ten times more if you sit with a lot of time and you don't know what to do with it. (P4)

For this participant the programme did not support them in meeting their needs, interests and level of skill. He was of the opinion that if the patients felt that they were presented with a choice of realistic vocational occupations, it would motivate their active participation in the programme.

I am a qualified electrician, I am a qualified plumber... do you think I want to come sit here in OT making necklaces or making beads? If you give a guy a piece of plank and say here is the wood, here is the machinery make me a coffee table I guarantee you there would be ten times more people there . (P4)

Theme 2: Overcoming constraints to occupational adaptation

This theme highlights the factors and adaptive strategies that facilitated occupational adaptation for the participants. It highlights the extent to which occupational engagement afforded the participants a sense of effectiveness and personal satisfaction as well as the factors that supported their attempts to overcome the constraints that they encountered. The theme has two categories:

Personal factors that facilitate adaptation

An important factor which assisted the participants to adapt to and cope with their hospitalisation was that of spirituality.

I feel like when I take my problems to the Lord that is the only time I can get through it (the programme). (P3)

They explained that their faith in God was an important component of their well-being and provided them with a sense of hope and motivation. Their spirituality assisted them to cope with their hospitalisation. This facilitated a change in their attitude towards their participation in the programme.

Your connection with God helps you a lot. He gives you the strength that you need; He gives you a fighting spirit... (P4)

Relying on support systems also served as an adaptation strategy that enabled the participants to overcome the challenge of being in hospital. Being able to draw on a support system that included family members and friends made in hospital was an important factor that contributed to this.

...some people you get very attached to, there is some people you get really, really attached to because there is no one else, that is a support structure...(P3)

They relied on personal resources such as positive thinking to cope with their hospitalisation. They expressed that positive thinking enabled them to cope with their prognosis and to encourage other patients at the same time.

With me, the doctors said the treatment is not working..I have been here for a year and eight or nine months and now I am going home.I didn't listen to what they told me, I decided that I am not going to give in. (P1)

Occupational factors that facilitate adaptation

Despite the constraints they experienced, the participants perceived that active participation in activities assisted them to adapt to the occupational demands they faced, resulting in positive changes in their occupational performance. For them, active participation implied making a concerted effort to maintain themselves and their daily routine.

And then I lay for a few seconds and then I say no, this can't happen, I can't lay like this. And then I get up and I make up my bed and I bath and get done. (P3)

The extent to which the choice of occupations met their needs was an important factor that motivated active participation. Some participants expressed a desire to succeed in their choice of occupations as evidenced by the goals that they set for themselves and the feelings of accomplishment that they associated with this.

I was thinking of making my own beads, that's what I always wanted.... It is a great opportunity for us to do all these things because if we leave here, back home we can do our own activities and start our own business. (P3)

... if I feel like I'm going to do something and I finish it then I will feel proud of myself and say that's my work, I did that, I finished that. (PI)

The sense of meaning and purpose they derived through their active performance of an activity assisted the participants to adapt to the demands of that activity and to subsequently make strides towards achieving their goals.

A lady at OT called me and asked me if I want to help wash the cars. At least I earned R32. So I could go and buy myself a cool drink ... u feel like.I did something to earn this money. (P2)

DISCUSSION

The rationale of this study emphasised the need to explore the role that occupational therapy could play in addressing poor treatment outcomes in MDR-TB patients. To this end, the researchers emphasised the importance of generating an understanding of how MDR-TB patients who undergo long-term hospitalisation experience and perceive occupational adaptation.

Occupational adaptation facilitated through engagement in daily occupations, has the ability to impact positively or negatively on health and well- being. Rudman33 states that occupation influences people's personal and social identity, while Kielhofner10 maintains that amongst other factors, occupational identity is shaped by people's interests, roles and routines as well as by their environmental contexts and demands. It can therefore be argued that being hospitalised had a negative influence on the participants' occupational identity as they articulated that the aforementioned issues contributed to the lack of personal fulfilment they experienced while hospitalised.

An inability to fulfil occupational roles and a lack of choice and opportunities for meaningful engagement in the activities presented at the hospital further illustrates the experience of occupational deprivation that manifested as a constraint to occupational adaptation21 by the participants. This resonates with Schkade and Schultz's9 view that the occupational adaptation process can be disrupted by stressful events. The participants indeed articulated that they experienced long-term hospitalisation as stressful evident in their complaints of a lack of freedom, autonomy and respect.

The participants experienced a loss of meaning particularly with regards to their inability to have control over their occupational choices which left them frustrated and angry at times. These findings concur with that of a study conducted by Farnworth and Munoz21 in which they concluded that highly structured, monotonous routines allow little opportunity or choice for purposeful occupational engagement, thus it becomes meaningless to the individual. This further illustrates the experience of occupational alienation by the participants which is associated with feelings of isolation and a loss of identity due to an individual's needs not being met by their occupational engagement.

Adaptive strategies constituting personal as well as occupational factors such as spirituality, having occupational choice and setting goals played an important role in facilitating occupational adaptation. This resonates with Schkade and Schultz's9 view of occupational adaptation as a process that includes the successful achievement of goals that can be assessed through perceived efficiency and satisfaction when adapting to occupational challenges. In this study, this was illustrated through one participant's active attempt to master the skill of beading in an effort to pursue her goal of income generation and achieve occupational competence. As this participant indicated that this was something that she always wanted to do, it can be argued that her occupational identity and competence improved after her participation in the beading, resonating with Kielhofner's10 view of occupational adaptation.

A noteworthy finding that was revealed by this study is the role that spirituality played in the participants' ability to cope with their circumstances. This highlights the importance of spirituality as an adaptive strategy and resonates with work done by Wilding34 on spirituality and occupation in which she asserts that spirituality can provide people with hope and meaning in everyday occupations. Weskamp and Ramugondo35 however question whether it is possible for people to have hope and achieve meaning and purpose in spirituality while experiencing occupational risks. They therefore assert that spirituality should be an integral part of interventions that address occupational risk factors such as occupational alienation.

CONCLUSION

This study generated a deeper understanding of the adaptive strategies that patients with MDR-TB who undergo long-term hospitalisation, at this hospital, used to adapt to occupational challenges. The study furthermore produced an understanding of the constraints to adaptation that they experienced. With this understanding the occupational therapy programme may be developed to more effectively facilitate occupational adaptation in this setting.

In the light of the participants' perceptions that the programme did not always support them in meeting their needs, interests and level of skill this study supports the argument of MSF7 as well as that of Swartz and Dick6 that the adoption of the client-centered approach is vital in the treatment of TB patients. In order to establish a therapeutic milieu within hospitals and achieve better treatment outcomes for MDR-TB patients, their needs have to be taken into consideration. This implies that the hospital should move away from a strictly biomedical approach and adopt a more integrated approach in which the patients' thoughts, feelings and needs are respected and decisions made collaboratively with them in order to achieve the best results. Occupational therapists can play a positive role in improving treatment outcomes for MDR-TB patients by addressing occupational risk factors that contribute to institutionalisation and by facilitating occupational adaptation through occupational enrichment programmes that accommodate patients' interests.

Occupational enrichment encompasses the deliberate adaptation of environments to facilitate meaningful occupations and provide people with opportunities for autonomous choice to support their personal development36. The use of psychosocial rehabilitation principles when implementing occupational enrichment in the programme is recommended by including activities that are meaningful and purposeful inclusive of spirituality, building support systems and income generation36. The utilisation of community resources and support systems will further encourage occupational adaptation and assist patients with community re-integration post discharge.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. WHO Global Tuberculosis Report. c2008. [Cited 22 June 2010]. Available from www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2008/. [ Links ]

2. Department of Health, South Africa. Management of Drug- resistant Tuberculosis: Draft Policy Guidelines. Department of Health, South Africa; 2008. [ Links ]

3. Department of Health, South Africa. National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines. Department of Health, South Africa; 2009. [ Links ]

4. Department of Health, South Africa. The Management of Drug Resistant Tuberculosis: Policy Guidelines. Department of Health South Africa; 2013. [ Links ]

5. Thaver V, Ogunbanjo G A. XDR TB in South Africa- What lies ahead? SA Family Practice, 48(10): 58- 59; 2006. [ Links ]

6. Swartz L, Dick J. Managing chronic diseases in less developed countries. British Medical Journal, 2002;324 : 914-915. [ Links ]

7. Medecins Sans Frontiers, South Africa. A patient- centred approach to drug resistant tuberculosis in the community: a pilot project in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Medecins Sans Frontiers, South Africa; 2009. [ Links ]

8. World Federation of Occupational Therapists (2004). Definition. [Cited 22 March 2009]. Available on http://medind.nic.in/iba/t05/iI/ibat05i2p47.pdf. [ Links ]

9. Schkade JK, Schultz S. Occupational Adaptation: Toward a holistic approach for contemporary practice: Part 2. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1992; 46(10): 917-925. [ Links ]

10. Kielhofner G. A Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application. 4th ed. Lipincott Williams & Wilkins: 2008. [ Links ]

11. Wilcock A.A. Occupational Risk Factors (Chapter 6,). In A.A. Wil-cock (Ed.). An Occupational Perspective of Health, Slack, Thorofare, NJ, 1998: 131- 162. [ Links ]

12. Gibson J.W. & Schkade J. K. Occupational adaptation intervention with patients with cerebrovascular accident: A clinical study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1997; 51: 523-529. [ Links ]

13. Klinger L. Occupational Adaptation: Perspectives of People with Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Occupational Science, 2005;12: 9-16. [ Links ]

14. Parsons L, Stanley M. The lived experiences of occupational adaptation following brain injury for people living in rural areas. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2008; 55(4): 231-238. [ Links ]

15. Cahill M, Connolly D, Stapleton T. Exploring occupational adaptation through the lives of women with multiple sclerosis. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2010; 73(3): 106-115. [ Links ]

16. Williams M, Murray C. The lived experience of older adults' occupational adaptation following a stroke. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2013; 60, 39-47. [ Links ]

17. Snowdown K, Molden G, Dudley D. Long- term illness. In: J. Creek (Ed.). Occupational Therapy and Mental Health. Churchill Livingstone, UK, 2001: 321-338. [ Links ]

18. Duncan, M. Occupation in the Criminal Justice System. In R Watson, L Swartz, editors. Transformation through Occupation. Whurr Publishers Ltd. London, UK.,2004: 129-142. [ Links ]

19. Barros DD, Ghirardi MI Lopes E. Social Occupational therapy. A Socio- Historical Perspective. In F Kronenberg, SS Algado, N Pollard, editors. Occupational Therapy without Borders: Learning from the Spirit of Survivors. Churchill Livingstone. London, UK, 2005: 140-151. [ Links ]

20. Bynon S, Wilding C, Eyres L. An innovative occupation- focused service to minimize deconditioning in hospital: Challenges and solutions. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2007; 54: 224- 227. [ Links ]

21. Farnworth L, Muhoz, JP An occupational and rehabilitation perspective for institutional practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 2009; 32(3): 578-584. [ Links ]

22. Walliman N. Social Research Methods. London, UK, Sage Publications, 2006. [ Links ]

23. Babbie E, Mouton J. Qualitative Studies. In E. Babbie, and J. Mouton editors. The Practice of Social Research. Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa 2001: 269- 312. [ Links ]

24. Henning E, van Rensburg, W Smit, B. Theoretical frameworks, conceptual frameworks and literature reviews (Chapter 2,). In Henning E, van Rensburg, W. & Smit B. editors. Finding Your Way in Qualitative Research. Van Schaik, Pretoria, 2004: 12- 27. [ Links ]

25. Terre Blanche M, Kelly K. Interpretive Methods. In M Terre Blanche and K Durrheim editors. Research in Practice: Applied Methods for the Social Sciences. University of Cape Town Press: Cape Town, South Africa. 1999: 123-146. [ Links ]

26. Jacelon CS. Participant Diaries as a Source of Data with Older Adults. Qualitative Health Research, 2005;15: 991- 997. [ Links ]

27. Ashbury J. Overview of Focus Group Research. Qualitative Health Research. Sage, London: 1995; 5(4): 414- 420. [ Links ]

28. Kitzinger J. Qualitative Reasearch: Introducing Focus Groups. British Medical |Qurnal, 1995; 311: 200- 302. [ Links ]

29. Hurworth R. Photo- interviewing for Research. Social Research Update (40). University of Surrey, Guilford, UK: 2003. [ Links ]

30. Braun V, Clarke V, Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006; 3: 77- 101. [ Links ]

31. Johnson B.R. Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. Education, 1997; 118(3): 282-292. [ Links ]

32. Mertens D. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Methods. 2nd rev.ed. Sage Publications, 2005. [ Links ]

33. Rudman DL. Linking Occupation and Identity: Lessons learned through qualitative research. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2002; 9(1): 12- 19. [ Links ]

34. Wilding C. Spirituality as Sustenance for Mental Health and Meaningful Doing: A case illustration. Medical Journal of Australia, 2007; 186 (10): 67-69. [ Links ]

35. Weskamp K, Ramugondo EL. Taking account of spiritualilty. In R, Watson, L, Swartz editors. Transformation through Occupation. Whurr Publishers Ltd. London, UK, 2004: 153-167 [ Links ]

36. Duncan, M. Promoting mental health through occupation (In R Watson, L Swartz editors. Transformation through Occupation. Whurr Publishers Ltd. London, UK, 2004: 198-219. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nousheena Firfirey

Nousheena.Firfirey@westerncape.gov.za