Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.44 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

SECTION 1

New insights in collective participation: A South African perspective

Fasloen AdamsI; Daleen CasteleijnII

IM Sc OT; Lecturer, Department of Occupational Therapy, School of therapeutic Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

IIB Occ Ther (UP), B Occ Ther (Hons) (Medunsa), PG Dip Vocational Rehabilitation (UP), Dip Higher Education and Training Practices (UP), M Occ Ther (UP), PhD (UP); Associate Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy School of Therapeutic Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

The concept of co-occupations or collectives occupations is gaining global recognition in occupational science and occupational therapy. However, little is known about the interpretation and understanding of this concept by occupational therapists in South Africa. The study aimed to explore community based occupational therapist's understanding of the concept of collective participation in occupations.

Purposive sampling was used to select participants. Data, gathered through semi-structured interviews, were analysed thematically.

The study yielded two themes namely; 'The whole is more than the sum of the parts' and 'I joined because of me, I stayed because of them'. Theme 1, describes the nature of the concept of collective participation while theme 2 describes the reasons for people to engage in collective participation.

All participants agreed that collective participation is an everyday occurrence within South Africa. The study found that mutuality and connectedness is needed for effective co-creating, which in turn is essential for collective participation in occupations. It is through this connectedness that a collective becomes more than the sum of the parts. The study also found innate needs for human beings to 'belong' and to 'survive' and an enabling and supportive environment are motivators for people to participate collectively in occupations.

Keywords: co-occupation, collective occupation, collective participation, collective

INTRODUCTION

In South Africa the majority of occupational therapists work in institutions in the health and education sector, however, services are now also branching out into community and social development sectors1. In these sectors therapists work with individuals, families and communities of people.

Within the occupational therapy literature a community is described as "groups of people acting collectively in a desired or needed occupation"21:210. This could be interpreted as a group of people coming together to work alongside each other. For example, a group of Zulu women working together to prepare food at a funeral, are collectively engaging in an occupation. Several authors are calling the latter co-occupations or collective occupations37.

The concept of collective or co-occupations has evolved over the last few decades3-5. Within Occupational Science, the premise is that human beings engage in occupations and activities daily throughout their lives and through this engagement they develop a repertoire of knowledge and skills8. Thus engagement in occupations is essential for all human beings as they are born with an inherent motivation to perform actions8. Initially the focus in the occupational science literature was on the individual person and the occupation. It looked at the individual's characteristics and how they match with the occupation that the person wants or needs to engage in. The impact of the environment on choices of occupations and how people engage in these occupations have also been described and debated9.

In the late nineteen-eighties and early nineteen-nineties, change occurred when certain occupational scientists argued that occupations are not always performed by only one person3-5,10,11. According to them, occupation is often shared and the collaboration between two or more people in the same occupation is essential for the success or failure of that occupation. This was the birth of the concept of co-occupation or collective occupations.

Pierce coined the term co-occupations4. She defined it as the interaction between the occupations of two or more individuals which consequently shapes the occupation of all the individuals3,4. Co-occupation involves a process that is interactive in nature and requires an active response from another person or persons involved in the occupation3,4. These responses or reciprocal interactions do not have to be symmetrical in nature3 as long as there is some form of interaction. Additionally, the interactions or responses are not only based on language or cognitive responses, but could be based on affective or physical process observations. According to Pierce3, co-occupations do not have to occur within shared space or time, and participants engaging in collective occupation do not have to have shared meaning or similar intentions although these do frequently accompany co-occupations. These occupations occur every day when people work together on tasks, projects, programmes or even when playing games6. For example, two people playing tennis. Each tennis player has his/her own motivation and skills to engage in the occupation, but usually the tennis players respond to each other's game and style of play. If one player changes the style of playing, the other also has to in order to be successful.

Pickens and Pizur-Barnekow5 further expand on the understanding of this concept by stating that for the occupation to be classified as a co-occupation there needs to be shared physicality, intentionality as well as shared emotionality components. All three areas are considered to be important, but for different co-occupations, the relationship between these three might vary. These three components contribute to the complexity of co-occupations.

Although the concept of co-occupation is becoming more prevalent in occupational therapy and occupational science literature, the concept of collective occupation is starting to emerge as a synonym. In their verbal presentation at the 15th Annual World Federation of Occupational Therapist congress, Ramugondo and Kronenberg defined collective occupation as "occupations that are engaged in by groups, communities and/or populations in everyday contexts, and may reflect a need for belonging, a collective intention towards social cohesion or dysfunction"7. When looking at this definition, the basic characteristics are similar to those of co-occupation as described above. Many authors and theorists describe the concept of collective and co-occupations, but little is known about the interpretation and understanding of this concept by occupational therapists in South Africa. This article attempted to clarify this issue. The findings reported in this article are based on the initial phase of a larger study to understand collective participation in occupations in order to develop a tool to measure the levels of collective participation.

Relevance of understanding this concept within a South African context

Public health and community based practice are commonly recognised subsections in the occupational therapy profession, not only in South Africa but globally2,3. For decades many occupational therapists have worked within community settings and, as other health professions, have addressed issues in South Africa that directly influence health4,5. These occupational therapists often have to plan and implement prevention and promotion programmes for groups of people in a community in order to enhance occupational health and to prevent occupational dysfunctions. Usually some form of collective participation by community members is essential for these programmes to be successful. An understanding of the nature of collective or co-occupations and collective participation would help these occupational therapists to better understand these concepts. This understanding could be used to facilitate optimal conditions for collective community participation in occupations which in turn could contribute significantly toward ensuring sustainability of programmes and projects within public health and community based settings.

METHODOLOGY

This study aims to explore occupational therapists' understanding of the concept of collective participation in occupation in the South African context. A qualitative research approach was used as little was known about the phenomenon under investigation and it must therefore be explored before it can be measured. A case-study research design was selected as this design is often used to explore unknown or complex phenomena within its context12. The case or unit of analysis in case study designs has been defined as "a phenomenon of some sort occuring in a bounded context"12:545. Baxter and Jack12 further define types of case studies. According to their descprition of instrumental case studies, researchers aim to imporve insight into an issue or help to refine a theory. The case is studied in depth, its contexts scrutinised and ordinary activities detailed. Therefore this initial phase of the larger research study may be described as an instrumental case study design12.

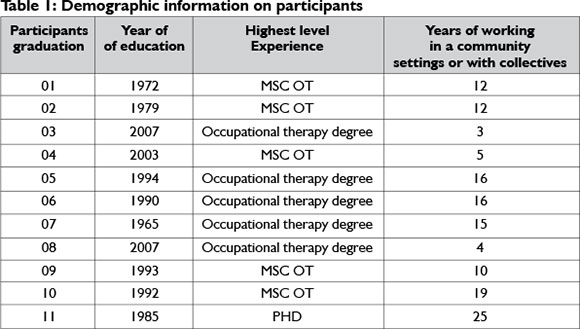

Semi-structured interviews were done with 11 participants. These participants were selected through a process of purposive sampling. Inclusion criteria required that each of the participants had to be an occupational therapists with more than three years' experience in a primary health care or community setting and familiar with the concept of collective participation in occupation in the South African context Within qualitative studies data is gathered until the same data emerge from different participants. At this point it can be assumed that data saturation has been reached13. In this study, sampling was continued until data saturation was reached which was after 10 interviews. By the 11th interview no new descriptions or ideas on collective participation were forthcoming. Although valuable information was shared during this interview, no new data were gathered although this interview was still included in analysis. Table 1 gives a profile of the participants in terms of when they graduated, highest level of education and years of experience working in community settings or with collectives. The sample predominately consisted of white females. These demographics represent the profile of occupational therapy in South Africa. A diverse group of participants were invited but consent to participate was received from the 11 participants described in Table 1.

Information gained through an occupational science literature review was used as a basis for the interviews. Interview questions focussed on the participants' understanding of the terms 'collective participation' and 'collective occupation'. Participants were asked what their understanding of the terms were, why they thought that people would participate collectively and why people would engage in collective occupations.

The semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically. An inductive analysis process was followed in line with the qualitative approach followed13. Codes were grouped together to form sub-categories. From these, categories and themes were formed. Member checking was done with two of the participants to validate data gained during this phase.

Ethical permission for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Witwatersrand, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. To ensure confidentiality, a code was allocated to each participant.

RESULTS

The study explored the terms collective participation and collective occupations and yielded two themes, 'The whole is more than the sum of the parts' and 'I joined because of me, I stayed because of them'. Theme 1 describes the nature of the concept of collective participation while theme 2 describes why people engage in collective participation (Table 2 on page 83).

The overall consensus was that collective participation or engaging in collective occupations is an everyday occurrence. People engage in collective participation on a daily basis, for example working together to finish a project, performing daily tasks, cooking for and feeding a group of people, or keeping a city clean and running. It takes place daily in work, social and home environments.

Participant 5: Yes, yes, there is such a thing as collective participation. Every day people do things together, whether it is playing rugby to people working together to make a play, to lecturers in the OT department... working together to ensure that students learn.

Theme 1: The whole is more than the sum of the parts (see Table 2 page 83 and Figure 1 page 86)

Participants felt that the nature of collective participation goes beyond the participation of a collection of individuals. To truly understand the potential of a collective, one has to look beyond the individual members of the group to the collective as a whole, for when they participate as a collective they have exponentially more potential than individuals working alone.

Participant 9: Whatever happens to create the system is a lot more than the sum total of the individuals in the system. It is exponentially more than that.

Participants in this research project often described the same concept in different ways. In essence it all came down to the fact that collective participation 'is more than the sum of its parts'. This concept is at the core of this theme. Emerging data from this project identify the underlying principles for collective participation in occupations as mutuality, connectedness and co-creating.

When looking at the nature of collective participation, 'mutuality' is found to be an essential component of collective participation. This concept highlights the reciprocal relationship that is needed for success in collective participation. Firstly; there needs to be mutual vulnerability that drives people to want to engage collectively. This vulnerability could be due to poverty.

Participant 7: ...like poverty. It often drives people to work together, whether it is a communal food garden or a soup kitchen. They want to make life better.

In this case the participant used an example of the mutual need of 'not having enough food' as a motivator for community members to work collectively to solve the problem. They could rally around a communal need and try to make life better for all involved. This would however not be successful if various people do not share this need, if they do not have a mutual need.

Secondly, they must share a similar vision of what they want to do or what they want to achieve.

Participant 9: We had a vision that we all believed in. That made us succeed.

In this case a mutual vision motivated the staff to work together to change the image of their institution after a negative incident. The staff had to revisit the vision of the institution and re-commit to it. This caused staff to pull together to work towards changing the perceived image and a mutual vision was one of the tools that made it possible for them to work together to do so.

Thirdly, collective participation should be mutually beneficial to the collective as well as to the individuals in the collective. Collectively members create opportunity for their skills and knowledge to develop by teaching each other or developing learning opportunities. Thus a characteristic of collective participation is mutual benefit, as all parties in the collective should benefit from being there.

Participant 11: Due to doing things with other people they felt more confident, they were able to problem-solve by themselves and able to organise things.

Lastly, mutual accountability and responsibility is one of the main components of collective participation.

Participant 2: Collective participation can only be successful if everyone takes responsibility.

As this is a situation in which people have to work together to make things happen, it is essential that everyone makes an effort to do their best to play their part effectively. By doing this they will be able to accomplish more as a collective and through sharing of responsibilities more actions can be performed and/or performance can be on a bigger scale. Thus the benefits could be exponentially greater if people work together.

It's about connectedness

Participants felt connectedness is the essence when looking at the nature of collective participation. For a collective to form a 'whole' that is more than the sum of the parts, people have to 'connect' with each other within the collective.

Participant 10: Without the connection there is nothing. If they do not connect with each other in the group they cannot perform together...

This connection is defined as one that goes beyond just being together physically or cognitively, although physicality could enhance connectedness. The connection also goes beyond just cognitive knowledge. Knowing why one is in a collective, what the collective stands for and what its purpose is, and how this aligns with the purpose and needs of the individual is important when a person joins a collective. This knowledge can be the start of cohesion as the person might feel that this is the right group, thus experiencing a feeling of belonging. The more cohesive the collective is, the easier it is for individuals in the collective to work together. This connectedness and cohesion can lead to individuals within the group developing a collective identity.

Participant 10: If you want a group to work, the cohesion and group belonging must be there. If it is not there it must be developed as soon as possible.

Through this cohesion the collective forms a collective identity. A collective identity as an essential component of collective participation emerged on numerous occasions.

Participant 5: A group consists of individual people, but together they are a collective group with their own collective identity.

When a collective forms, it develops a collective identity that goes beyond the individuals in the group.

Participant 10: If you look at each one separately they would not have ended up doing what they did, so that for me was a very good example of this. They [the group] form an identity that is totally different from the individual... I would go so far as to say if there are 10 people in the group, the collective identity is the 11th person, because this identity is not just a sum of the other people in the group, but more than that.

This participant highlighted an incident which occurred when she was facilitating a series of closed groups. During this time the group members participated collectively in an activity that she (as the group facilitater) would not expect them to participate in. In her opinion, they would not have participated in this activity if each member was alone, but collectively they had the confidence to do it. This collective confidence changed their collective identity. This identity went beyond just the identity of the combined individual members, but it was a new identity that they developed as a collective; thus the whole was not equal to the sum of the parts but more than the sum of the parts.

Co-creating beyond what the individual can do

Lastly, for a collective to be more than the sum of the parts, it needs to co-create. The concept of 'create' is commonly understood as 'to make' or 'to produce'. It is the product of the energy spent and can bring something new into existence or change a current context or situation. Through collective participation, the collective could be working together to address collective problems, to work towards a collective vision.

Participant 7: But it is important that they work together. One person might be able to do it, but not as effectively as a few together.

The last quote highlights the fact that for collective participation to occur, parties need to work together and interact with each other. This interaction could be a symbiotic relationship where they work together to achieve success. Often the outcome of these actions benefits all involved. As indicated by the quote above, some of these tasks can be done by individuals, but completion of it in a collective is often more beneficial and effective.

Participant 4: My husband and I look after our children together every day. I do some things and he does some things, but ultimately we parent together. If one of us doesn't participate it's not going to be successful... you understand what I mean?

On the other hand parties involved in collective occupations can also work against each other and these actions might be detrimental to all involved or could be beneficial to only one of the parties involved. A collective positive outcome is thus not vital for collective participation but it is preferable. It is the process of participating and interacting that defines the term, not necessarily the outcome. If individuals participate well collectively they might have a positive outcome. On the other hand, if collective participation is fragmented, uncoordinated or disharmonious, the outcome may not be positive.

By participating collectively to achieve certain outcomes, the collective is co-creating, thus harnessing group strength in the form of their collective knowledge, skills and strengths to achieve their collective goals and visions. This could be more effective than if they were trying to create changes individually. As a collective they have greater strengths than if they addressed the problems as individuals.

Theme 2: I joined because of me, I stayed because of them (see Table 3 page 84)

This theme describes the participants' understanding of reasons why people engage in collective participation. These reasons are described in three main categories. Firstly, the participants felt that people engage in collective action because being part of a group met certain personal conscious and unconscious needs that are often individualistic needs. Secondly, a supportive, enabling environment makes it possible for the person not only to want to participate collectively, but also to continue this practice. If the collective environment is enabling and fulfils their needs, people often choose to stay in the collective. Lastly, people are more motivated to participate collectively if they perceive the participation as being successful and they can see a difference.

The majority of the participants felt that the choice to participate collectively is usually motivated by an individualistic need of the person rather than a more collective need of the community. These needs relate to their basic innate needs as human beings but also their more individualistic personal needs.

Emerging data from this project highlights two opposing opinions on this point.

Firstly, this individualistic focussed motivation is driven by a basic innate need of human beings to be connected to other human beings.

Participant 04: "Humans are essentially social beings. We want to belong to a group." Participant 02: "As human beings we are made to want to connect. It is.... a human thing..."

The above-mentioned participant summarised the point when she said that human beings participate in collectives mainly because they have a basic need to belong to a group. Being part of collective addresses this innate need. Socialisation was not highlighted as an origin of this need, but an inherent knowledge possessed by all human beings or a 'collective unconsciousness' was reported as the origin.

Participant 09: Being African means that we part of a collective and our culture is based on Ubuntu...

The above quote, which was expressed in various ways by different participants, supports the findings of the 'collective unconsciousness'. Through this, people have an understanding of the importance of working collectively as well as how their need fits into the need of the collective and how their contribution could be beneficial for the community that they live in, which in-turn could benefit them as well.

Participant 11: Working in, for example, a communal garden is about Ubuntu, both you and the community benefit.

Participant 09 took this point further by adding, . but we struggle with Western influences that dictate looking after yourself and your family first.

It is important at this point to note that although many participants talked about the inherent need for people to belong to a group, the individualistic approach of the Western world was also brought into the discussion. It was in contrast to Ubuntu. This was clarified by various participants who said that although as human beings we still have the innate need to belong, our needs are often more individualistic. The quote below summarised it well:

Participant 06: ...here is the wonderful dichotomy of life that is dialectic between individualism and cooperative living.

On the other hand, in direct conflict with a human's need to be part of a collective, data from this research have highlighted the human being's innate need to survive on an individualistic basis as another reason for people joining or participating in collective action. People join collectives because it is beneficial for them to survive (to improve their situation).

Participant 6: So I'm saying it is an animal thing...individualism...it is instinct.

This participant feels that human beings have an innate motivation to survive and our actions are often focussing on this need. She continues to justify this by stating:

Participant 6: Still, it is that basic drivers... Maslow's lower rings are making us individualistic, first me and then you.

Due to this innate need, as human beings our actions focus first on our own and our family's survival before focussing on the needs of others. This does not mean that we cannot understand others' needs or that we do not consider the needs of others. It means that our actions will focus on the individualistic needs first.

In summary, these innate needs reported by the participants are motivators for people to participate in collective action. By joining or participating in a group, their needs as a human being can be met.

As indicated at the beginning of this theme, data highlighted two reasons why collective participation is motivated by individualistic needs. The first reason was highlighted above; the second reason was that of individual needs within the social context that motivates collective participation. These reasons are more influenced by society, socialization and the person's own situation and context. This suggests that people join collectives for personal gain, thus making this motivation egocentric.

Participant 11: People participate in their community because they see some benefit to themselves.

People participate in collectives because they see it as an opportunity to change their situation for themselves or their families. Additionally, people could join the collective to address the problems in their occupational settings. They could possibly address these problems on an individualist level, but from experience they might have learnt that it is easier to achieve certain outcomes in a collective.

Participant 03: ...it takes individuals connecting and acting collectively to make a difference."

On the other hand, participating in a group also gives a person the opportunity to share information with others and to help others to develop certain skills. In essence they help others to develop themselves. It makes them feel good about themselves, and could give meaning to their lives if they can help others. This could also validate their knowledge and skills. The participants saw this as one of the important motivators to joining collectives for people whose basic needs have been met.

Lastly, people join and participate in collectives as it addresses a need to act within their beliefs or values. Various participants talked about the belief in a higher power and how this belief motivates participation.

Participant 08: ...They believe that they need to do good to others then they will participate for the greater community. They formed like a women's group or something like that to address the issues.

Collective participation needs a supportive and enabling environment for it to be effective. Emerging data from this research highlights the fact that people often participate collectively for their own individual gain, but they stay in a collective in response to the support and feedback they get from the group. Participants felt that the supportive nature of the collective and the enabling community environment that the collective interacts with are reasons why people participate collectively. They have to feel comfortable in the group.

Participant 10: Nine out of 10 times people stay because the group supports and helps them. Why would they stay if they do not get anything out of being in a collective as you put it?

People also stay in a collective if they see that the collective actions they participated in were successful. If collective participation leads to achievement of their collective outcomes and vision, members could be motivated to stay. Fulfilment of individualistic needs and seeing individualistic benefits due to participating in a collective also act as motivators for people to continue their participation.

DISCUSSION

Collective participation in an occupation or occupations is seen as an interaction between various members in a collective to achieve an outcome that could benefit the collective as well as the individuals in the collective. When trying to understand the nature of collective participation we should look at the process of interaction and not specifically the outcomes of the interaction.

For occupational therapists it is important to understand the nature of collective participation and to do this we need to consider Gestalt theory13. Underpinning this theory was the principle from Aristotle who said "The whole is better than the sum of its parts". In 1935, Koffka adjusted this by stating that the whole is not specifically 'more' that the sum of the parts, but 'something different' from the some of the parts. Thus, the 'whole' develops its own identity13,14. Therefore, if we apply this theory to collective participation in an occupation or occupations, the fact that this/these occupation(s) is/are performed by a collective makes it more beneficial for not only the individuals in the collective, but to the collective as a whole. The results of theme 1 align with the above theory. The participants talked about a group identity that goes beyond the collective identities of the group members, and this could make the outcome greater than could have been achieve by an individuals working alone, or by groups of people working in a collective but not connected to other members of the group.

In this case the mutuality, including the mutual vulnerabilities, vision, benefits, accountability and responsibilities develops and enhances the feeling of 'connectedness' that is an essential component of collective participation. This connectedness makes it possible for members of the collective to co-create successfully. It is through this connectedness that the collective becomes 'more than' or 'different from' the sum of the parts and start interacting together to ensure successful co-creation of occupations. By co-creating occupations, outcomes beneficial to all parties involved can be co-created as well.

As occupational therapists we need to consider how groups of people work together to contribute to one or a series of occupations. If we only look at the 'sum of the parts', our understanding of the community may not be complete. We need to understand what makes collectives function optimally and how to enhance collective participation, as optimal collective participation is essential for community development.

The findings of theme 1 are also in line with those of Pickens and Pizur-Barnekow5 who state that the nature of collective or co-occupation is that it should have shared physicality, intentionality as well as shared emotionality components. However, the results of this study found that although physicality could develop the 'connectedness' faster, it is not essential for co-creating occupations. What is essential is the mutuality which in part is similar to Pickens and Pizur-Barnekow's 'emotionality' and 'intentionality'5.

This study also found that people are driven to participate in collective action due to innate human needs as well as individualistic personal and social needs. The innate human need is related to the human beings' need to belong to a collective and to want to engage in occupations with others. This is in line with the findings of Oy-serman, Coon and Kammelmeier14 who carried out a meta-analysis of studies assessing individualism and/or collectivism. After coding 27 scales they found eight similarities in the scale for collectivism. One of these was 'belonging" which was described as "wanting to belong to, and enjoy, being part of groups"14:9.

As indicated in this study, the reason for this need to belong is two-folded. Firstly, it is an innate need for human beings to be part of a collective as they want to belong. Reasons for this need to belong and need to engage in a collective was attributed to a collective unconscious that participants describe as internal consciousness of the benefits of working in a collective to ensure safety, and progress. When looking at history, man has always participated in collective occupations, whether working in the fields to ensure that there is enough food to get through winter, to waging war against their enemy. In South Africa this collective participation contribute towards 'Ubuntu'. The term 'Ubuntu' is not easily defined and has many interpretations, including a 'sense of common humanity'l5, and "a person can only be a person through others" (originally by Arch Bishop Tutu)l6. It is the last interpretation of the term that participants in this research project alluded to i.e. the person's identity is defined and developed by those around, thus an understanding that a human being is not alone but part of a collective.

On the other hand the drive to participate in a collective is related to the innate need to survive and improve one's own situation. For example, in South Africa community members have learnt through years of experience that collective action is more powerful than individual action. The collective voice is often heard and better acknowledged by government than individual voices. This knowledge drives community members to join collectives in order to achieve positive change in their community and for themselves as seen in service related riots or strikes for better salaries. Mass or collective action was found to be more powerful than individual action.

Individuals respond to the innate drive to survive and to improve their curcumstances by joining a collective that could protect them and that could give voice to their concerns, thus reducing their feelings of powerlessness.

The motivation towards collective participation in occupations is also influenced by the enabling environment of the collective and the skills and knowledge gained in the collective. The more enabling the environment, the more motivated a person is to engage in, and to continue engaging in, this this enabling environment. This is influenced by an open attitude amongst members, a welcoming atmosphere in the group and during meetings as well as the collective cohesion discussed earlier. For a disempowered person, this could be a very nurturing environment that develops their confidence and increases their feelings of hope that their situation could change for the better17. This feeling of hope is described by Yalom as 'instilling hope' and means that a person experiences feelings of hope when they see other people who are in the same situation as they are coping and improving their situation18. This gives them hope that it can also happen to them. An enabling group environment could also develop members' skills and knowledge, and create opportunity for them to develop their confidence by getting positive feedback from other members in the group. Lastly, an enabling environment creates opportunity for individual members to feel that their fears, insecurities and problems are not unique and that others also have these. Joining a group where people have similar problems is common, but finding out that people in a collective have similar fears and concerns as you can be cathartic and make them feel less alone. This is what Yalom calls 'universality'l8.

So what could this mean for occupational therapists working with collectives?

As stated previously, many occupational therapists are working in community based settings with communities or collectives which have to engage in collective occupations to enhance their health and to develop their community. It is thus imperative for these occupational therapists to understand the nature of collective participation as well as understand why people engage in it. This information could be used by occupational therapists to ensure that they facilitate optimal participation in collective occupations by creating an environment that makes it attractive and easy for people to engage collectively. This, in turn, could lead to improved participation in preventative and promotive programmes within health and social services.

In conclusion, this study looked at the nature of collective participation in occupations and why people engage collectively. The results found that collective participation is a common occurrence that happens daily. Collective participation is a symbiotic interaction between various parties that could benefit a collective and the individuals in a collective. Mutual vulnerabilities, visions, benefits and accountability, create a connection that makes it possible for a collective to co-create.

The study also found that people participate in collective occupations due to innate needs as well as personal needs, and an enabling collective environment makes it possible to continue collective participation.

With this enhanced understanding of collective participation, we now have to develop tools and methods to better understand specific communities' or collectives' readiness or ability to participate collectively. This would be the next step in ensuring we understand collective participation.

REFERENCES

1. Leclair LL. Re-examining Concepts of Occupation and Occupationa-based Models: Occupational Therapy and Community Development. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2010; 77 (1): 15-21. [ Links ]

2. Polgar JM, Landry JE. Occupation as a Means to Individual and group Participation in Life. In: Townsend E, Christiansen CH, editors. Introduction to Occupation: The Art and Science of Living. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2004. [ Links ]

3. Pierce D, Marshall A. Staging the Play: Maternal Management of Home Space and Time to Facilitate infant/ todller play and development. In: Esdaile SA, Olson JA, editors. Mothering Occupations: Challenge, Agency and Participation. Philadephia: F A Davis; 2004. [ Links ]

4. Pierce D. Co-occupation: The Challenges of Defining Concepts Original to Occupational Science. Journal of Occupational Science, 2009; 16 (3): 203-7. [ Links ]

5. Pickens ND, Pizur-Barnekow K. Co-occupation: Extending the Dialogue. Journal of Occupational Science, 2009; 16 (3): 151-6. [ Links ]

6. Pizur-Barnekow K, Knutson J. A Comparision of the Personality Dimensions and Behaviour Changes that Occurs During Solitary and Co-occupations. Journal of Occupational Science, 2009; 16 (3): 157-62. [ Links ]

7. Ramugondo E, Kronenberg FF Collective Occupations: A Vehicle for Building and Maintaining Working Relationships. l5th World Congress of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists; Santiago, Chilli2010. [ Links ]

8. Cutchin MP, Aldrich RM, Bailliard AL, Coppola S. Action Theories of Occupational Science: The Contribution of Dewey Bourdieu. Journal of Occupational Science, 2008; 15 (3): 157-65. [ Links ]

9. Nelson DL. Occupational Form. Journal of Occupational Science, 1999; 6 (2): 76-8. [ Links ]

10. Dickie V, Cutchin MP, Humphry R. Occupation as Transactional Experience: A Critiques ofIndividualism in Occupational Science. Journal of Occupational Science, 2006; 13 (1): 83-93. [ Links ]

11. Fogelberg D, Fraiwirth S. A Complexity Science Approach to Occupation: Moving Beyond the Individual. Journal of Occupational Science,2010; 17 (3): 131-9. [ Links ]

12. Baxter P Jack S. Qualitative casestudy methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researches. The Qualitative Report, 2008; 13 (4): 544-59. [ Links ]

13. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. California: Sage Publishers, 2002. [ Links ]

14. Oyserman D, Coon H, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking Individualism and Collectivism: Evaluation of Theoretical Assumptions and Meta-Analysis. Psychology Bullitin,202; 128 (1): 3-72. [ Links ]

15. Nussbaum B. Ubuntu: Reflections of South African on Our Common Humanity. Reflections,2003; 4 (4): 21-6. [ Links ]

16. Jolley D. 'Ubuntu': A person is a person through other Persons. Utah: Southern Utah University; 2010. [ Links ]

17. Albertyn MR. Conceptualisation and Measurement of the Empowerment of Workers: An Educational Perspective. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch; 2000. [ Links ]

18. Yalom ID. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 1980. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Fasloen Adams

Fasloen.Adams@wits.ac.za