Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.43 n.3 Pretoria Mar. 2013

ARTICLES

The effect of a two-week sensory diet on fussy infants with regulatory sensory processing disorder

Jacqueline JorgeI; Patricia Ann de WittII; Denise FranzsenIII

IB OccTher (Pret) MSc OT (Wits). Postgraduate Student Occupational Therapy Department, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Science, University of Witwatersrand Paediatric Occupational Therapy Practice: Sensory Matters Inc

IIOT (Pret) MSc OT (Wits). Adjunct Professor and Head, Dept of Occupational Therapy Department, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Science, University of the Witwatersrand

IIIB Sc OT (Wits) MSc OT (Wits) DHT (Pret). Senior Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Science, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the effectiveness of a two-week programme of parent education and a sensory diet to reduce signs of fussiness in infants identified with Regulatory Sensory Processing Disorder (RSPD). The sensory diet was viewed as a complementary programme and was based on the Sensory Integration theory of Jean Ayers. The sample consisted of twelve infants who met the diagnostic criteria for RSPD. Data were gathered using the Infant Toddler Symptom Checklist and a parent interview. Infants were divided into two combined age bands as prescribed for the administration of the Infant Toddler Symptom Checklist. One group fell into the age band of 7-12 months of age and the other into the 13-24 months age band. Pre and post intervention measures allowed for comparison of data to determine the effect of the programme.

Findings for this sample indicated a significant reduction in signs of fussiness in both groups (p<0.00), with a greater change evident in the 7-12 month group. The most significant changes were seen in self-regulatory and attachment behaviours. Difficulties with tactile, vestibular and auditory sensitivities related to sensory processing persisted indicating the need for further sensory integrative therapy.

Parents reported a lack of knowledge and recognition of Regulatory Sensory Processing Disorder in infants by health professionals and as a result, there had been no referral to occupational therapists for sensory integration therapy in this sample group. Despite the small sample size, the results contribute to the emerging understanding of the influence of sensory modulation on dysfunctional infant behaviour.

Key words: Regulatory Sensory Processing Disorder, Sensory Integration, Sensory diet, Infant Toddler Symptom Checklist, Fussy infants.

INTRODUCTION

During normal development, self-regulation develops as infants learn to take interest in their surroundings, while at the same time regulating their level of arousal in response to sensory stimulation1. This self-regulation is described as an interaction between physiological maturation; the parents' sensitivity to the infants' needs as well as the infant's adaptation to the environmental demands. The foundation for self-regulation is the infant's ability to develop homeostasis during the early months of life. This process continues to develop during the first two years of life2. Homeostasis refers to the ability of the infant to regulate and develop sleep-wake cycles, to digest food, to self soothe in response to changing stimuli from the environment and to respond appropriately to social stimuli3.

For some infants this natural process of self-regulation does not develop typically. As a result they may have difficulties in transitioning between arousal states, become overwhelmed quickly and avoid self soothing behaviours such as sucking their fingers or dummies. They often dislike swaddling and move into extension patterns when crying and irritable. This impacts homeostatic functions such as being able to feed and sleep adequately4. Some infants demonstrating these behaviours have been described as meeting the criteria for Regulation Sensory Processing Disorder (RSPD). This disorder is evident early in life5 and it has been reported in infants older than six months who appear to be fussy, irritable, with poor self-calming behaviours and who show intolerance to change6,7. This set of behaviours affects daily adaptation, interactions and relationships7. While the causes of RSPD are unclear it appears to be linked to accentuated neurological thresholds for sensory, motor, psychological and behaviour processes7. Suggestions of an overlap with difficult temperament, atypical central nervous system function and genetic factors have been reported6. Problems with physiological maturation, caregiver response or the infant's adaptation to environmental demands may also play a role in the development of RSPD8,9.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sensory Integration was described by Ayers in 1972 as "the neurological processes that organises sensation from one's own body and from the environment and makes is possible to use the body effectively within the environment"10:103.

Sensory integration intervention has been said to emphasise an approach which addresses "the sensory needs of the child in order for the child to make adaptive and organised responses to a variety of circumstances and environments"11:17. Ayers' theory of Sensory Integration is well recognised within occupational therapy and has been the departure point for later research and theory development by other occupational therapists, such as de Gangi and colleagues in 1993 and 19952,3. To differentiate Ayers' original theory and body of knowledge from further expanded research, assessment protocols and intervention models, it was trademarked as Ayers Sensory Integration® in 200712.

The programme described in this paper was based on the principles of Ayers' theory of Sensory Integration10 together with complementary programmes as provided through of a sensory diet13 and parent education. Through this it was hoped to increase understanding of the infant's behaviour and facilitate change.

A 'sensory diet' refers to a planned and scheduled activity programme which draws on the principles of Ayers' theory10 and is designed by an occupational therapist to meet a child's specific and unique sensory needs14. Sensory diets are described by Wilbarger15 and Faure4,16,17. However there is limited published research on sensory diets for infants. Sensory diets are viewed as being complementary to sensory integration based on Ayers' theory15. The principles guiding the design of sensory diets are organised around everyday activities and routines such as when an infant is touched, dressed, fed or bathed4,6. It includes modifying daily routines, changing the environment and using individualised sensory stimulation to normalise specific sensory responses13.

The development of self regulation

The process of self-regulation at each stage of development refers to an infant's ability to perceive and modulate sensory information and is dependent on the infant's ability to maintain the 'four A's18. The four A's are inter-related concepts which together result in self regulation. They refer to the infants' ability to maintain an appropriate level of arousal (the ability to maintain alertness and transition smoothly between states of being asleep and awake); the infant's ability to attend selectively to a task; an affective or emotional response and lastly an action or an adaptive goal-directed behaviour.

In the early months, an infant is unable to effectively apply self-regulatory behaviours and is reliant on his/her parents and the environment to provide appropriate sensory modulation. The infant then begins to learn to modulate sensory stimuli and self-regulate through parent-infant interactions using tactile, vestibular, auditory and visual experiences6. Sensory integration therefore occurs as he/ she learns to modify his/her actions in relation to the environment. Self-control begins to emerge from 18 months of age as the child is able to use language and play to internalise routines and instructions from others6.

The diagnosis of RSPD is made during infancy when self-regulatory or sensory modulation difficulties disrupt daily routines and activities such as sleep, feeding, and play. It may also result in emotional or behavioural challenges such as frequent emotional outbursts and poor adaptability to change5. Lane confirmed that RSPD is identified only in infancy, although these infants may possibly present later with a sensory processing disorder if their difficulties persist19.

In investigating the effectiveness of a programme to alleviate RSPD, it was important to explore the level of understanding and awareness of the condition amongst health professionals in South Africa. The disorder was first described in 2006 in the USA and has not been classified in either the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10)20 or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - Text Revised (DSM IV - TR)21. Regulatory Sensory Processing Disorders are only described in the Diagnostic Manual for Infancy and Early Childhood Mental Health, Developmental, Regulatory-Sensory Processing, Language and Learning Disorders (ICDL-DMIC) of the Interdisciplinary Council on Developmental and Learning Disorders22. This manual is not yet in common use in South Africa, therefore, the diagnosis of RSPD is infrequently made in South Africa.

The tools that may be used to assess RSPD in infants are the Infant Toddler Symptom Checklist (ITSC)2 and the Test of Sensory Functions in Infants (TSFI)23. The ITSC used in this study is a valuable tool for occupational therapists as it focusses on the occupational performance areas of sleeping, eating/feeding, dressing and bathing. The items on this test allow parents to observe and report on their experience of their infant's fussiness. The test has been standardised and assesses a range of behavioural and sensory domains including: self-regulation, attention, touch, movement, listening and language, looking and sight as well as attachment.

The ITSC was designed to assess infants in the 7 to 30 months age range, with six checklists that cover the following age bands: 7 to 9 months; 10 to 12 months; 13 to 18 months; 19 to 24 months; and 25 to 30 months. At risk scores which indicate regulatory and sensory disorders are provided for each age band2.

The ITSC was initially developed in 1987 by DeGangi et al with 57 items organised into nine behavioural domains2. In the standardising procedure and to establish norms, the items were tested on a sample of predominantly middle-class Caucasian infants in the USA2. Thirty infants who were developing typically and 15 infants with RSPD were included in the pilot study. After analysis and revision of items, data collection was conducted over a three year period. The test was then validated on two samples of infants between 7 and 30 months of whom 154 were developing typically and 67 who had been identified with RSPD. To date reliability of the test has not been reported. Construct validity was established by comparing the scores of the sample of infants with regulatory disorders to that of infants whose parents were not concerned about their infants' behaviour2. Results indicated that the majority of infants whose parents were concerned about their child's' behaviour met the criteria for being at risk for RSPD while all those whose parents were not concerned did not meet the criteria set to indentify this disorder. The authors report that 78% of infants identified by the ITSC as having problems were later diagnosed with developmental or behavioural problems when assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist2. The inclusion criteria reported in this paper are the same as those used in the reported studies, which were used to determine whether infants could be identified as having RSPD2.

Intervention approaches for RSPD

An integrated, family-centred treatment model has been identified by Gomez, Baird and Jung24 and DeGangi13 as being valuable in planning intervention. DeGangi suggests three formal approaches including parent guidance, child-centred interactions which are based on developmental individual differences, and thirdly, Ayers Sensory Integration13. No published research could be found on the long-term prevention of developmental, learning, sensory integrative, behaviour and emotional difficulties by providing intervention in infancy for RSPD. It has also not been determined what duration, frequency and type of intervention would work best25.

The activities for the intervention programme described in this paper were based on the work of Williamson and Anzalone1 and Faure17 who specify the alerting or calming stimuli which can be used for infants and toddlers.

Calming vestibular stimuli that include rhythmic activities, such as rocking and swaying as well as proprioceptive stimuli that include resistive activities and deep pressure to the joints and muscles were identified as being of particular importance26. Other calming sensory stimuli used included tactile stimuli through deep, firm touch, such as holding the infant firmly for a hug or rhythmic patting; oral stimuli like sucking a dummy; and auditory stimuli in the form of music with a steady, slow rhythm1.

Sensory strategies for feeding difficulties were based on the baby-led weaning approach, developed by Rapley and Murkett27. In addition, scheduling feeding at a relaxed time, the development of a predictable routine, or sequence of events, and the slow introduction of different food textures were advocated28.

Intervention for sleep difficulties were based on studies of normal sleep patterns in infants that incorporated principles related to night time sleep patterns and the ability to self-soothe. Burnham et al.29 described infants spending most of their sleep time in their own cots and parents waiting before responding to infant awakenings as the two main indicators of improved self-soothing in infants at 12 months of age. They reported that an infant's ability to fall and stay asleep was influenced by specific sensory modulation difficulties related to auditory, tactile or vestibular processing.

AIM OF THE STUDY

The aim of this study was to explore whether 7 to 24 months old infants with fussy behaviour would respond to an intervention programme consisting of a two-week sensory diet and parent education.

The objectives of the study were:

♣ to assess selected infants with fussy behaviour to establish if they met the diagnostic criteria for RSPD;

♣ to administer pre-and post parent-reported checklists of infants' behaviour;

♣ to implement and evaluate a two week programme of parent education and a sensory diet for the infants;

♣ to establish the effectiveness of the intervention through statistical analysis of the comparison of the pre and post checklists;

♣ to establish what the parents of infants with RSPD knew about the condition and what advice they had previously obtained from health professionals in dealing with the condition.

METHODS

This study design was a quantitative, descriptive study using a pre- and post-intervention checklist to determine the effect of a programme of a sensory diet and parent education on infants who met the diagnostic criteria for RSPD. A survey design was used to determine the parents' knowledge about RSPD and what help they had received in dealing with their infant's problems and the effectiveness of this help. The research procedure followed a pre-intervention, intervention and post-intervention process.

Study population and sample

Interested clinic sisters at six private baby clinics in the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan area of South Africa were provided with research flyers and checklist with inclusion criteria so they could identify possible participants. Infant participants were included in the study if they met at least two the following inclusion criteria:

♣ Sleep disturbances where the infant takes more than 20 minutes to fall asleep or wakes more than twice a night;

♣ Difficulties in self-consoling where the parent spends two to four hours a day attempting to calm the infant;

♣ Feeding disorders not related to allergies or intolerance including refusal to eat, regurgitation and difficulties establishing a regular feeding routine;

♣ Hyper-arousal where the infant appears overwhelmed by sensory input, avert gaze to avoid contact and appear intense, wide-eyed or hyper-active.

The clinic sisters were requested to inform the parents if the infants that met these criteria about the research and to give them the researcher's contact details. This selection method allowed for voluntary participation as parents could decide whether or not to contact the researcher and participate in the study. Infants were excluded if they were medically unhealthy or had a medical condition which explained excessive fussy behaviour, for example, soft cleft palate affecting feeding.

The study sample consisted of 12 infants, between the ages of 7 and 24 months, identified by their parents as fussy. Of the 12 participants included in the study, seven of participants were male and five were female. Six participants were aged between 7 and 12 months and six were between 13 and 24 months. Infants aged six months or younger were not included, as fussiness at this age can be associated with the high incidence of colic and reflux3. Toddlers from 24-36 months were also excluded as fussiness in this age group is to be considered developmentally appropriate2.

Research procedure

A telephonic screening interview was carried out with the parent that contacted the researcher to ensure that infants met the inclusion criteria and to obtain informed consent for participation in the study. If this was the case the parent was invited to participate in thestudy. Appointments were made at their convenience at their home,work or the researcher's private practice for interview purposes.

Three data collection tools were used to collect the pre-intervention data. Firstly a questionnaire was completed by the parent that detailed demographic information, medical details of the pregnancy and birth of the child.

The researcher interviewed the parent to explore the infant's history and symptoms of fussiness. Survey questions about the parents' knowledge of RSPD, what help the parent had sought regarding their child's fussiness and the effectiveness of this help were included in the interview. Finally the parent was asked to complete the parent self-report Infant-Toddler Symptom Checklist(ITSC)2, which was then scored and reviewed by the researcher. The ITSC assesses self-regulation, attention, touch, movement, listening and language, looking and sight as well as attachment and is a valuable tool for occupational therapy as it focuses on occupational performance areas like sleep, eating or feeding, dressing, bathing, in which the parent's experience their infant's fussiness. The ITSC was designed for the 7- to 30-month age range, with six checklists that cover five different age bands, 7 to 9 months, 10 to 12 months, 13 to 18 months, 19 to 24 months, and 25 to 30 months. Cut off scores which indicate regulatory and sensory disorders are provided for each age band2.

The intervention consisted of two parts namely parent education and the provision of the sensory diet. Parents were educated about RSPD and sensory modulation. The impact of the condition on occupational performance in sleep, feeding and attachment were presented verbally using supporting diagrams.

The two-week sensory diet home programme was prescribed for each infant and designed to address each infant participant's specific sensory and behavioural dysfunction based on information obtained from the ITSC and the interview questionnaire.

Following the intervention, the parent completed the second ITSC and provided feedback on the effects of the implemented sensory diet. The ITSC was scored by the researcher and the parent's progress report was reviewed.

For analysis purposes the sample was divided into two groups (7 - 12 months and 13 - 24 months) due to the clustering of the behavioural domains assessed and the 'at-risk' criteria for dysfunction which differ for the age bands on the ITSC2.

The pre and post-intervention total ITSC scores were compared to the RSPD criteria indicating dysfunction2. Non-parametric statistics were employed due to the small sample size (n= 12) and the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to analyse whether change had occurred30.

RESULTS

Clinic sisters and paediatricians interviewed prior to this study were unaware of this relatively new diagnostic manual and attributed symptoms associated with RSPD or fussy behaviour in infants to colic and/or reflux. This was true even when symptoms presented after the age of six months, although it is recognised that colic typically resolves by six months of age through natural maturation3. If symptoms persist after the age of six months, a referral is recommended by the researcher to establish if the behaviours are related to RSPD and whether early intervention is indicated.

Effectiveness of the intervention programme

Results of the ITSC total sample analysis revealed a significant decrease in the mean ITSC behavioural domains of the test and total scores for the entire sample at the end of the two-week intervention period (p < 0.00). A large effect size of 1.47, according to Cohen's d calculation was found post intervention which indicates a 73.1% improvement within the group and places the difference between the pre and post intervention scores on the 93rd percentile.

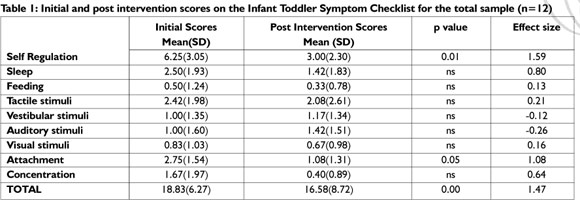

There was a varying change in the different behavioural domains assessed by the ITSC with the scores decreasing in all domains indicating improvement, except for the vestibular and auditory stimuli which show that the scores increased (Table 1).

Significant improvement was found for self-regulation (p< 0.01) and attachment (p< 0.005). Effect size for self-regulation after the intervention was 1.59.

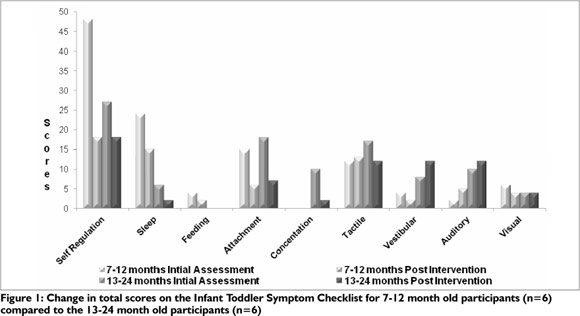

Results for two age groups: 7-12 months age group and 13-24 months age group

Figure 1 indicates that there was a significant change (p < 0.025) in the total mean scores for the 7-12 months age group after the two-week intervention period, with an overall effect size of 2.15. The self-regulation (p < 0.05) domain showed significant change with a medium effect size of 0.5 or a 33% improvement. The tactile and auditory domains scores increased after intervention.

The total mean scores for the ITSC for the infants between 13 and 24 showed a large effect size of 1.11 after the intervention. When the various domains of the ITSC were analysed for the 1 3-24 month old infants none of the domains showed significant change although there was improvement in four domains (Figure 1). The scores for the vestibular and auditory domains increased and the visual domain was unchanged.

A small effect size was found for attachment (0.87), self-regulation (0.64) and concentration (0.68).

Parent perceptions and actions

Parents were asked to identify when signs of RSPD were first noted in their infant. Six reported that their infant was fussy from birth and three from six weeks old. Another two reported the fussiness starting between four and six months and one parent stated that the fussiness was only noted from 7 months. When asked to rate their greatest concerns in relation to RSPD, parents were most concerned about sleep (35%), self-regulation and feeding (13%), followed by attachment (8%).

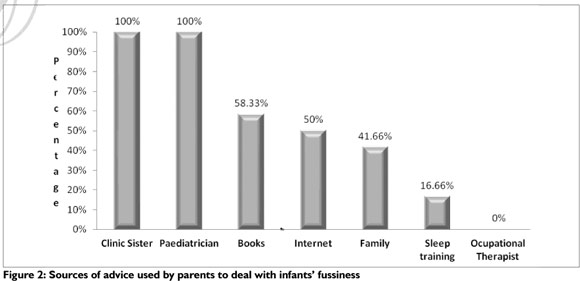

The parents sought advice from multiple sources to deal with their infant with all parents having sought advice from their paediatricians and clinic sisters (Figure 2 on page 32).

Only one parent reported that they had heard of RSPD and nine other parents felt that knowledge about the condition and the possibility of intervention would have resulted in relief and a more positive response. Three sets of parents preferred that their infant not be given a specific diagnosis.

None of the infants in the study had been referred for occupational therapy but three parents had heard of Sensory Integration from colleagues or experienced it in therapy with their older children.

DISCUSSION

Parents reported observing signs of fussiness in their infants earlier than six months of age, with 50% reporting fussiness from birth and 25% from six weeks. Further research would be needed in a younger age group to establish how the fussiness relates to colic and whether the symptoms of RSPD were present and contributing to problems before the age of six months.

The concerns parents had about their infant's sleep, self-regulation, feeding attachment and general fussiness led them to approach clinic sisters, paediatricians and other sources for help. However, parents reported that the advice given, along with information from books and the internet did not adequately equip them to deal with their infants' problems31,32.. The lack of referral to occupational therapists appears to confirm a lack of awareness of RSPD amongst health professionals dealing with infants. Furthermore, there appears to be a lack of knowledge of sensory integration- based intervention in treating this condition. Thus more teamwork between disciplines and education about regulatory disorders for other professionals is required.

From the inclusion criteria designed to identify infants for this study, it appeared that the criteria provided an accurate, quick screening method, as all the identified infants obtained at risk scores on the ITSC2. By implication, the criteria could be used by other health professionals to identify possible cases of RSPD, for referral to a Sensory Integration trained occupational therapist. However, these findings will need to be confirmed in future research on a larger sample size.

The assessment of the infants' behaviour and the description of their fussiness in the study relied strongly on parental perceptions during pre and post-testing. This method was chosen as the researcher felt that the parents would be in the best position to indicate a reduction in signs of RSPD as they had the most contact with the child. The reliability of this method of assessment in determining change could thus not be confirmed. Therefore, the researcher ensured that the parents had a sound understanding of the condition and understood how to implement the sensory diet appropriately. Parent education empowered them to be able to judge if change had occurred.

The researcher felt that educating the parents on RSPD provided an opportunity for parents to interact with their infants in different ways. The importance of parent education on addressing their infants dysfunction is supported by two studies which specifically assessed the parents' perspectives on the benefits of education as part of the therapeutic process31,32. This may suggest that, in some cases, rather than the infants improving, changes reported were due to the change in parental knowledge and understanding of RSPD and not necessarily in objective changes in infants' symptoms. This variable can be addressed in future research by the addition of the Test of Sensory Functions in Infants23 which is completed by an occupational therapist and not the parents.

The use of a sensory diet home programme for a two-week period appeared to have empowered parents' with strategies which they could incorporate into everyday tasks in their busy lives. This form of indirect therapeutic intervention allowed parents to implement the programme and fit it into their daily schedules. However, these results need to be confirmed in a study with a larger sample size and for a longer period of intervention, across a variety of age bands.

A tentative conclusion was that the sensory diet home programme was beneficial to the infants with a significant improvement in the mean total score on the ITSC after the two-week intervention period. All infants displayed a reduction in signs of RSPD with seven of the 12 infants moving to within the normal range and were to deemed no longer be at risk for RSPD. Although five of the infants remained at risk for RSPD, four of the five showed a six or more point improvement on the ITSC with an effect size of 1.47. It would be beneficial to reassess the infants at 36 months, to determine the long-term effects of the intervention. This would have allowed a comparison with other studies which were conducted over a longer period3,33.

In analysing the specific changes for all the infants in the behaviour and sensory domains assessed by the ITSC, self-regulation and attachment showed significant improvement. These two constructs of the ITSC deal with infant interaction with others, such as being able to self-soothe independently, the amount of sensory stimuli tolerated before becoming overwhelmed, time spent calming the infant and separation anxiety. Positive changes in these areas, therefore, affect interaction between the parent and infant.

Although improvements in sleep were reported, the changes were not found to be statistically significant. This may be accredited to the ITSC sleep item taking only into consideration infants with a wake frequency of above three times per night as well as difficulty returning to sleep. Sleep problems found in this study, which included aspects like an inconsistent sleep routine, taking a long time to fall asleep but once asleep either sleeping through or waking once a night, were not assessed. Thus the ITSC was not always sensitive to improvements in the problems reported.

When considering the results of the two age groups separately, the 7-12 month group showed the greatest difference in regulation and the most significant change, with a large effect size of 2.15 between pre and post-testing on total ITSC scores. In this group, there was a significant improvement in self-regulation difficulties, improvement in sleep and attachment difficulties but a slight increase in tactile and auditory difficulties.

The 13-24 month group also showed a large effect size of 1.11 between pre and post-testing on total ITSC scores, even though the initial assessment identified less dysfunction. In this group the vestibular and auditory difficulties increased slightly indicating, as with the 7-12 month old group, that the sensory integrative-based treatment may require individualised sensory integration intervention. The sensory diet home programme improved only the behavioural and emotional components as assessed on the ITSC. These results are similar to those of DeGangi et al.25 who found improvements in behaviour and emotional regulation in 36 month old children who received 12 weeks of intervention during infancy. Vestibular and tactile sensitivities persisted in their sample, as in this study. These findings were not unexpected as the sensory diet was based on sensory strategies used to manage behaviour in occupational performance areas of dressing, bathing, feeding and sleeping1,6. The intervention activities focussed on providing calming and organising vestibular, proprioceptive and deep pressure stimuli. Sensory processing and underlying modulation difficulties in the infants were not addressed in this study. The greater improvement seen in the younger group could also be attributed to the habit-formation around the behaviours being less established and the parents of the older infants being less willing to follow through with some strategies.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

In quantitative research using statistical analysis, a large sample size usually provides confidence in the generalisability of the results. In this study, both the sample size and the short period of intervention limit the confidence of interpretation. The results are therefore should be interpreted with caution.

As the sample size of this study was only 12 infants increasing the possibility of a Type II error30 effect size was used to determine changes in both groups of infants. Cohen's d effect size analysis was used to determine the size of difference between the total, pre and post-intervention scores30. An effect size of more than 1 standard deviation was considered significant for this study, while an effect size of 0.5 standard deviation was seen as a moderate change.

CONCLUSION

Although this study was conducted on a small sample, it demonstrated a significant change after the two-week intervention period. It also provided valuable information for current practice in South Africa regarding the lack of awareness of RSPD and knowledge of Ayres -Sensory Integration based occupational therapy as a therapeutic intervention to assist in managing this condition.

This study obtained valuable information pertaining to RSPD in infant participants, regardless of the small sample size. The study showed that parents recognised children as being unusually fussy within a very short period after birth (75% before 6 weeks), but they did not recognise it as a condition which might require intervention. This might be because these infants were confirmed by paediatricians as being medically healthy. Other health professionals did not recognise that unusual fussiness may be indicative of RSPD and therefore did not know how to advise parents or refer them to an occupational therapist. The fact that the diagnostic manual describing RSPD is not commonly used in South Africa contributes to this problem.

The results of this study contribute to the emerging understanding of the potential benefits of a sensory diet as an early intervention to reduce fussiness in infants. Despite the fact that the results cannot be generalised before further research with a large sample, it may guide occupational therapy Sensory Integration practice to explore the use of similar strategies required for infants presenting with RSPD in clinical practice. The study suggested that infants presenting with high attachment and poor self-regulation scores may benefit from parent education and a sensory diet home programme to manage RSPD. Those presenting with specific and severe sensory-based processing difficulties may require individualised Sensory Integration therapy by a certified occupational therapist.

REFERENCES

1. Williamson G, Anzalone M. Sensory Integration and Self-Regulation in Infants and Toddlers: Helping Very Young Children Interact with Their Environment. Los Angeles: Zero to Three; 2001. [ Links ]

2. DeGangi G, Poisson S, Sickel R Wiener A. Infant/Toddler Symptom Checklist. Texas: Therapy Skill Builders; 1995. [ Links ]

3. DeGangi G, Porgess S, Sickel R, Greenspan S. Four year follow up of a sample of regulatory disordered infants. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1993; 14(4): 330 - 343. [ Links ]

4. Faure M. Your sensory baby. Harlow: Dorling Kindersley Limited; 2011. [ Links ]

5. Miller L, Anzalone M, Lane S, Cermak S, Odten E. Concept evolution in sensory integration: a proposed nosology for diagnosis. Amercian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007; 61(2): 135-140. [ Links ]

6. DeGangi G. Pediatric Disorders of Regulation in Affect and Behavior: a Therapist's guide to assessment and treatment San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [ Links ]

7. Reebye P Stalker A. Understanding regulation disorders of sensory processing in children: managements strategies for parents and professionals London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007. [ Links ]

8. Greenspan S, DeGangi G, Wieder S. The functional emotional assessment scale (FEAS) for infancy & early childhood. Bethesda. ICDL Press. 2001. [ Links ]

9. Reebye P Stalker A. Regulation disorders of sensory processing in infants and young children. BCMJ. 2007; 49(4): p. 194-200. [ Links ]

10. Ayres A. Sensory integration and learning disorders Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1972. [ Links ]

11. Spitzer S, Smith Roley, S. Sensory integration revisited: A philosophy or practice. In Smith Roley S, Blanche EI; Schaaf RC, eds. Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations. San Antonio, Therapy Skill Builders; 2001. 3-27. [ Links ]

12. Smith Roley S, Mailloux Z; Miller-Kuhaneck H; Glennon T. Understanding Ayers Sensory Integration. American Occupational Therapy Association. 2007 September; 12(17). [ Links ]

13. DeGangi G. An Integrated intervention approach to treating infants and young chidlren with regulatory, sensory processing, and interactional problems. In The Interdisciplinary Council on Developmental and Learning Disoders. (ICDL) Clinical practice guidelines. Baltimore: ICDL Press 215-242. [ Links ]

14. Biel L, Peske N. Raising a sensory smart child. London: Penguin Books; 2009. [ Links ]

15. Bundy A, Lane S, Murray E. Sensory Integration Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2002. [ Links ]

16. Faure M, Richardson A. Sleep senseWelgemoed: Metz Press; 2007. [ Links ]

17. Faure M, Richarson A. Baby Sense Welgemoed: Metz Press; 2000. [ Links ]

18. Lester B, Freier K, LaGasse L. Prenatal cocaine exposure and child outcome: what do we really know. In Williamson G, Anzalone M. Sensory integration and self regulatoin in infants and toddlers: helping very young children interact with their environment. Los Angeles: Zero to Three; 2001. 18-21. [ Links ]

19. Lane S. Interview with Dr Shelly Lane. 2012. Held with the researcher in South Africa. [ Links ]

20. World Health Organisation. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th ed). Geneva:; WHO. 2007. [ Links ]

21. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR: 4th Edition Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [ Links ]

22. Interdisciplinary Council on Developmental and Learning Disorders. Diagnostic Manual for Infancy and Early Childhood. Bethesda: ICDL Press; 2005. [ Links ]

23. DeGangi G, Greenspan S. Test of Sensory Functions in Infants (TSFI) Manual Philadelphia: Western Psychological Services; 1989. [ Links ]

24. Gomez C, Baird S, Jung L. Regulatory Disorder Indentification, Diagnosis, and Intervention Planning. Infants and Young Children. 2004; 17(4): 327-339. [ Links ]

25. DeGangi G, Sickel R Wiener A, Kaplan E. Fussy babies: to treat or not to treat? British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996 October; 59(10): 457-464. [ Links ]

26. Case-Smith J. An efficacy study of occupational therapy with high-risk neonates. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1988; 42(8): 499-505. [ Links ]

27. Rapley G, Murkett T. Baby-led weaning: Helping your baby to love good food. London: Vermilion; 2008. [ Links ]

28. Chatoor I. Sensory food aversions in infants and toddlers. Zero to Three. 2009; 29(3): 44-49. [ Links ]

29. Burnham M, Goodlin-Jones B, Gaylor E, Anders T. Nightime sleep-wake patterns and self soothing from birth to one year of age: a longitudinal interventions study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002; 43(6): 713-725. [ Links ]

30. Kielhofner G. Research in Occupational Therapy: Methods of Inquiry for Enhancing Practice Pliladelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2006. [ Links ]

31. Cohn E. Parent perspectives of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001; 55(3): 285-294. [ Links ]

32. Cohn E, Miller L, Tickle-Degnen L. Parental hopes for therapy outcomes: children with sensory modulation disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000; 54(1): 36-43. [ Links ]

33. DeGangi G, Breinbauer C, Roosevelt J, Porgess S, Greenspan S. Prediction of childhood problems at three years in children experiencing disorders of regulation during infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2000; 21(3): 156-175. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jacqueline Jorge

jackquijorge@iafrica.com