Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Reading & Writing

On-line version ISSN 2308-1422

Print version ISSN 2079-8245

Reading & Writing vol.10 n.1 Cape Town 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/rw.v10i1.241

'Students will be able to pass this module without using the textbook.' (LB, Engineering, female)

The students realise that the lecturer will review the needed sections of the textbook and so they are not forced to develop their reading in order to become better readers:

'We start with the lecturer's slides so we know what is going on. That way we won't look at unnecessary information in the textbook.' (S11, Economic and Management Sciences, male)

This cycle indicates that students themselves realise that they need to develop their reading abilities, but they would rather be non-compliant readers than take active steps to improve their reading abilities. The fact that lecturers take responsibility to 'teach' textbook content to students (e.g. identifying core aspects that could also be asked in tests etc.) reinforces students' non-compliance and their reading abilities are not improved. These findings on the negative cycle of non-compliance are supported by Ryan (cited in Hoeft 2012:2) and Bean (2001:134). Non-compliance and low reading ability definitely hinder students' reading development.

Barriers within the text

According to all 14 lecturers, the textbook they prescribed for their module was suitable for first-year students. It seemed as though the lecturers matched the outcomes of the module to the content of a textbook. As one lecturer justified:

'It is the only textbook available about the subject which is specifically suited for first-year students.' (LA, Natural Sciences, male)

The majority of students held a different opinion on their textbooks. They thought many of their textbooks were too 'difficult' and 'unnecessary'. This difference in opinion can be due to a 'mismatch' of students' reading abilities and the difficulty levels of the textbooks. The opinion of students that the textbooks were not suitable can also be traced back to the fact that reading was not essential in many of their modules. A student's frustration with realising that reading a textbook was, in fact, not necessary is evident from the following comment:

'The lecturer would say "prepare chapter 7 of the textbook" and he literally only uses a few points, and there I go and study the whole chapter, where I could have just like done something else.' (S2, Humanities, female)

The opinion of students that the textbooks were unsuitable can additionally be ascribed to the availability of other texts in the module. Students in different focus groups and two lecturers stated that it was not necessary for students to read the textbook with reference to certain modules. One lecturer said that she 'helped' the students by preparing notes which the students could photocopy. As a result, students had little or no use for the textbook.

Students depended on the lecturer to give the gist of the content and expected to be 'trained' for assessment and, in many cases, the lecturers met their expectations. This seems to nurture a non-reading culture where students can pass the module by only attending class and studying notes. In fact, from the analyses of all seven focus group interviews, it was clear that most students made use of notes as a primary text. These notes either took the form of 'handouts' from the lecturers' PowerPoint presentations, or were notes compiled by a peer. Furthermore, it became clear that selling and buying module notes was a practice among students. Students preferred these notes because information was summarised, to the point, and the key concepts were identified. These notes were, in many cases, the only text necessary to 'read' to complete tasks. The following comment made by a student indicates how the availability of notes influenced his perception of the necessity of reading:

'In the beginning of the year, I really studied from that textbook. Then when the test came, I did poorly. The next time I did not open the textbook, I just studied the notes. Now I've learnt my lesson.' (S1, Engineering, male)

The availability of notes partly influences students to adapt such a pragmatic approach to reading. Students run a 'cost-benefit analysis' when it comes to prescribed academic reading as they determine the minimum reading investment that will help them reach at least the minimum task requirements (Schwartz n.d:1; Del Principe & Ihara 2016:203). It seems that using information for different purposes is a characteristic of the current generation of students generally referred to as millennials. Morreale and Staley (2016:357) note that this generation of students 'are more likely to repurpose, recycle, and reuse information from others for their own creative purposes' than read seminal works and build their own knowledge. When other texts are available such as notes, and students can use the notes to complete the task, students see no reason to 'go to all the trouble' to read the textbook. It seemed as though students stopped looking for information when they found it in the slides. They generally do not read the textbook after they have studied the slides. This is definitely a barrier to their reading development.

Barriers within the task

From the data analysed it is clear that students and lecturers had different perceptions about reading as a requirement for task completion. All the lecturers remarked that students needed to read the prescribed texts to be able to complete the task. Different lecturers used the word 'force' as the following comments indicate:

'The purpose of the tests is to force students to work through the content.' (LB, Natural Sciences, male)

'The individual tests definitely force students to read the textbook.' (LA, Economic and Management Sciences, female)

The lecturers generally communicated the requirement of reading before starting the task, by providing students with relevant page numbers and informing them that reading is important. The link between the text and the task was clear to the lecturers, as they designed the tasks. For the students, however, the link between the text and the task was generally vague and in some cases absent. The barrier related to the task as variable seemed to be the format of the task.

To illustrate this barrier, I will discuss two examples. In one specific module, students had to give a presentation on a chapter in the textbook. The students worked together in groups of 10. According to the students, not all members took responsibility to read the chapter:

'I do not like the group work. Not everyone read the book. Just those who had to talk made sure they read the chapter.' (S2, Economic and Management Sciences, male)

In the second example, the students in one of the focus groups explained that one of their tasks was a tutorial class test. This test took place during a set time, where the students had to answer a set of questions using their textbook. Discussions among students were allowed and a lecturer was present. According to the students, the format of this tutorial test led to very little reading, but a lot of discussion, which they clearly preferred:

'I think it is much quicker when someone tells you something, than when you have to read a whole paragraph in detail. It takes long to read, reread and try to make sense of everything.' (S1, Natural Sciences, male)

During the focus group interviews students mentioned that they were content with 'getting by' (i.e. achieving a pass mark of 50% for a task). Students remarked that they would always try to find 'the easy way out' in terms of task completion, which would lead to at least 50%. In other words, if the format of the task is group work where one can depend on another student to read the chapter, or a tutorial where peers and the lecturer are present to discuss difficulties, it is conceivable that for a goal of 50% task achievement, such tasks will lead to little or no reading development.

Barriers within the socio-cultural context

Within the socio-cultural context, the barriers of throughput pressure and lecturers' assumptions were uncovered. In the higher education environment, there is pressure to grant students access to university and make sure that they succeed. It seems as though lecturers experience pressure from institutional managers who are running a university like a business. More students equal more government subsidy and so throughput must be ensured. The following comments of two lecturers support this statement:

'I am of the opinion that lecturers do not pressure students to struggle with the textbook on their own, because all lecturers are under pressure to have a good throughput rate of students in their modules. As a result, the lecturers take on more and more responsibility and the students take on less and less. That negatively impacts the way students engage with their textbooks.' (LB, Natural Sciences, male)

'I also think that you have to find a balance between throughput figures in your module and knowledge that the students need to obtain. There is a lot of pressure not to have students fail your module, so it is not going to work if the material is too difficult. I try to achieve this balance with tutor classes and having the technical aspects of the essay count as much as the content of the essay. However a student can pass my module without doing a lot of reading, as long as they attend classes and do the needed assignments.' (LB, Humanities, female)

Throughput pressure is one of the barriers to reading as it seemed to increase lecturers' willingness to make their slides and notes available to their students. It also influenced the tasks they designed (including the format), as is clear from the comment that the technical elements of an essay count as much as the content, for example. When lecturers, as important role players within the socio-cultural context, make choices based on the pressure to help as many students as possible to pass their module, reading development can be hampered.

From the students' perspective it is understandable that they would not deem reading the textbook as an essential activity, as the lecturers provide summarised texts. It seemed as though this help is superficial. When lecturers make notes available that summarise a section of content, the students are deprived of a reading development opportunity to learn how one goes about making summaries from a section of a textbook. When students can attain 50% for a task by making sure the technical aspects are in place, for example, they are also in a way deprived of the responsibility to produce well-written content, like a well-structured argument, for example. This assumption also leads to a dependency on the lecturer as students do not learn how to be independent scholars - something they will need increasingly as they continue with further studies.

Lecturer's assumptions were another barrier that I uncovered within the socio-cultural context. Lecturers seemed to assume that their students can read independently and that students intuitively know how to 'use' scholarly discourse, in other words, what is expected in the discipline in terms of scholarly engagement. The following comments of different lecturers illustrate these assumptions:

'I cannot understand why students do not do well in this module. It is very straightforward. The students have to read, remember and give the information in a test.' (LA, Economic and Management Sciences, female)

'They should have read something before they enter my class.' (LA, Law, female)

'I think the vocabulary and language (of the textbook) are suitable for first-year students. I do not think it is difficult.' (LA, Natural Sciences, female)

From the data analyses of the focus groups, it seemed that many of the students are not independent readers and struggle with scholarly engagement:

'I just look at the [text]book and I get drained.' (S8, Humanities, female)

'With one of my modules I read and read, and I still don't understand.' (S1, Education, female)

I think the textbook of this one module is way too complicated.' (S5, Education, female)

'The textbook compresses the information in such a way that it is there, but it is not there.' (S3, Economic and Management Sciences, male)

'It [reading the textbook and completing a certain task] is nothing like that which we did at school. We do not understand it well.' (S4, Natural Sciences, male)

Because of the assumption that students should be prepared for scholarly engagement and reading, the interviewed lecturers did not seem to make any provision for students' reading development. Students seemed discouraged about their own reading practices within the context of their modules. They seem to realise that their reading abilities are not meeting the lecturers' expectations, but they are unsure how this can be remedied. One student remarked that he did not fare well in a task and that in future he is going to read the notes 'better'. This is ironic because the student failed to realise the core issue: he was not reading the textbook, but rather someone else's summarised version of it. I am of the opinion that lecturers' assumptions create a distance between the lecturers and the reading development needs of the students.

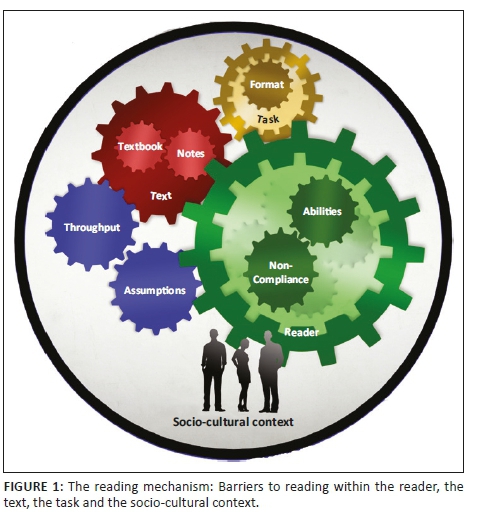

The reading mechanism

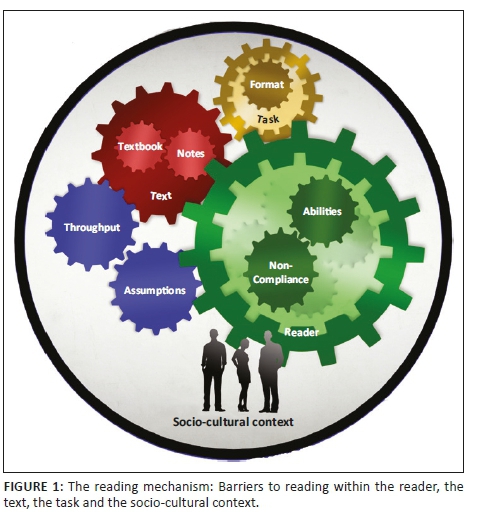

As the final part of the results, I present a visual representation as a summary of the discussed reading barriers (see Figure 1). This representation was developed through a combination of theory and the findings of this qualitative study. As stated, reading is the product of the interaction of variables (RAND Reading Study Group 2012). Based on this view of the reading process, I present the interrelated variables as cogs in a mechanism. In this visual representation, the barriers are presented as smaller 'broken' cogs that obstruct the functioning of the bigger cogs and thus also the functioning of the reading mechanism. This metaphor indicates that the uncovered barriers hamper students' reading development.

Ethical consideration

The setting of the study was the Potchefstroom campus of the NWU. The study population was first-year students and lecturers responsible for first-year modules. As the highest attrition occurs in the first year of study (Scott et al. 2007), first-year students and their lecturers were chosen as participants. All participants volunteered to take part in this study and approval was obtained from the university's ethics committee.

Conclusion

Higher education institutions in South Africa have a responsibility to help the students who gain access to a tertiary education to succeed. From a lifespan developmental perspective on reading, all students can develop into competent readers; they just need to be provided for (Alexander 2005). If reading is understood as the interaction between the variables of the reader, text and task within a socio-cultural context (RAND Reading Study Group 2002:11), generic reading support cannot be the answer to our students' reading challenges. A handful of academic literacy practitioners or support staff cannot effectively help undergraduates from different faculties to, for example, read their chemistry textbooks or court cases. The lecturer teaching academic content is a critical role player in students' reading development. As is clear from the visual representation in Figure 1, the lecturer usually decides on the task (design and format) and the text (including whether or not to make notes available). These choices influence the reading process. Although reading abilities and non-compliance are barriers within the reader, we cannot place the responsibility for reading development squarely on the shoulders of our students. They do not have a reading 'illness' that can be 'cured'. In my opinion they are new apprentices in need of guidance from an insider within a discourse community (Gee 2003). In my mind, there is no better insider than the lecturer.

It is a fact that the South African school system is not preparing our students optimally for university. The academic literacy and support departments can definitely contribute to improve students' academic literacy, of which reading is an integral part. However, other role players like lecturers, faculty boards and institutional management should move beyond blame shifting to accountability in terms of students' reading development. Van de Poel and Van Dyk (2014:172) refer to a collaborative approach. Lecturers are appointed at universities because of their expertise in a certain discipline. As lecturers, the teaching and learning policy of the university states that they should guide students to reach module outcomes 'through active learning activities suitable to the level of autonomy expected at a certain level' (North-West University 2011:1). Disciplinary experts do not necessarily have knowledge of what constitutes such a suitable activity and might therefore be unable to design activities that closely link the text and the task so as to aid students' reading development. The teaching and learning support structure of a university includes individuals who are skilled in developing active learning activities and have knowledge of the reading process, but they lack disciplinary knowledge. The Education Sciences faculty can also contribute in terms of how reading support should feature within curriculum design. Such a team effort can possibly result in synergy between disciplines, the fostering of a relationship between role players who take responsibility and students who have the needed opportunity to develop their reading abilities.

The aim of this article was to uncover reading barriers that students and lecturers perceive so that role players can gain insight into the reading support needed at higher education institutions. One limitation of the study is that the uncovered barriers might only exist for the specific context in which the study took place. It will be naive to think that addressing each separate barrier will help students to read better. It would not be theoretically sound to take the reading 'mechanism' apart and attempt to 'fix' the separate cogs. All role players have to understand that reading is an interconnected and complex process. Role players, especially lecturers, should take cognisance of some of the reading barriers that lecturers unintentionally cause and students unknowingly experience, and how the variables of the reader, the text and the task influence each other within the context of a discipline. In this way, we can move a step closer towards collaboratively planning the developmental reading opportunities our students need as opposed to the limited generic reading support that is presently offered.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express her gratitude to Prof. Carisma Nel for her expert guidance in this research project. Also thank you to all the lecturers and students who participated and were willing to share their experiences.

Competing interests

I declare that I have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced me in writing this article.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Alexander, P.A., 2005, 'The path to competence: A lifespan developmental perspective on reading', Journal of Literacy Research 37(4), 413-436. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3704_1 [ Links ]

Andrianatos, K., 2018, 'First year university students' reading strategies and comprehension : Implications for academic reading support', PhD thesis, Faculty of Education Sciences, North-West University. [ Links ]

Archer, A., 2006, 'A multimodal approach to academic "literacies": Problematising the visual/verbal divide', Language and Education 20(6), 449-462. https://doi.org/10.2167/le677.0 [ Links ]

Bean, J.C., 2001, Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Berndt, A., Petzer, D.J. & Wayland, J.P., 2014, 'Comprehension of marketing research texts among South African students: An investigation', South African Journal of Higher Education 28(1), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.20853/28-1-321 [ Links ]

Bernstein, B., 1999, 'Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay', British Journal of Sociology of Education 20(2), 157-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995380 [ Links ]

Bharuthram, S., 2012, 'Making a case for the teaching of reading across the curriculum in higher education', South African Journal of Education 32(2), 205-214. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n2a557 [ Links ]

Bharuthram, S. & Clarence, S., 2015, 'Teaching academic reading as a disciplinary knowledge practice in higher education', South African Journal of Higher Education 29(2), 42-55. [ Links ]

Boakye, N., Sommerville, J. & Debusho, L., 2014, 'The relationship between socio-affective factors and reading proficiency: Implications for tertiary reading instruction', Journal for Language Teaching 48(1), 173-213. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v48i1.9 [ Links ]

Butler, G., 2013, 'Discipline-specific versus generic academic literacy intervention for university education: An issue of impact?', Journal for Language Teaching 47(2), 71-87. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v47i2.4 [ Links ]

Del Principe, A. & Ihara, R., 2016, '"I bought the book and I didn't need it": What reading looks like at an urban community college', Teaching English in the Two Year College 43(3), 229-244. [ Links ]

Gee, J.P., 1990, Social linguistics and literacies: Ideologies in discourses, Falmer, London.

Gee, J.P., 2003, What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Haggis, T., 2009, 'What have we been thinking of? A critical overview of 40 years of student learning research in higher education', Studies in Higher Education 34(4), 377-390. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771903 [ Links ]

Hallett, F., 2013, 'Study support and the development of academic literacy in higher education: A phenomenographic analysis', Teaching in Higher Education 18(5), 518-530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.752725 [ Links ]

Hoeft, M.E., 2012, 'Why university students don't read: What professors can do to increase compliance', International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 6(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060212 [ Links ]

Howard, P.J., Gorzycki, M., Desa, G. & Allen, D.D., 2018, 'Academic reading: Comparing students' and faculty perceptions of its value, practice, and pedagogy', Journal of College Reading and Learning 48(3), 189-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2018.1472942 [ Links ]

Jacobs, C., 2007, 'Towards a critical understanding of the teaching of discipline-specific academic literacies: Making the tacit explicit', Journal of Education 41(1), 59-81. [ Links ]

Joubert, I., Hartell, C. & Lombard, K. (eds.), 2016, Navorsing: ʼn gids vir die beginner navorser, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

MacMillan, M., 2014, 'Student connections with academic texts: A phenomenographic study of reading', Teaching in Higher Education 19(8), 943-954. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.934345 [ Links ]

Maree, K., 2007, First steps in research, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

McLoughlin, K. & Dwolatzky, B., 2014, 'The information gap in higher education in South Africa', South African Journal of Higher Education 28(2), 584-604. https://doi.org/10.20853/28-2-344 [ Links ]

Morreale, S.P. & Staley, C.M., 2016, 'Millennials, teaching and learning, and the elephant in the college classroom', Communication Education 65(3), 370-373. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2016.1177842 [ Links ]

Nel, C., Dreyer, C. & Klopper, M., 2004, 'An analysis of reading profiles of first-year students at Potchefstroom University: A cross-sectional study and a case study', South African Journal of Education 24(1), 95-103. [ Links ]

Niven, P.M., 2005, 'Exploring first year students' and their lecturers' constructions of what it means to read in a humanities discipline: A conflict of frames?', South African Journal of Higher Education 19(4), 777-789. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v19i4.25667 [ Links ]

North-West University, 2011, Teaching and learning policy, viewed 22 November 2017, from http://www.nwu.ac.za/sites/www.nwu.ac.za/files/files/i-governance-management/policy/8P-8_%20TLA%20policy_e.pdf.

Pretorius, E.J., 2002, 'Reading ability and academic performance in South Africa: Are we fiddling while Rome is burning', Language Matters 9(33), 169-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228190208566183 [ Links ]

Pretorius, E.J., 2005, 'What do students do when they read to learn? Lessons from five case studies', South African Journal of Higher Education 19(4), 790-812. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v19i4.25668 [ Links ]

RAND Reading Study Group, 2002, Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension, RAND, Santa Monica, CA.

Schoenbach, R., Greenleaf, C. & Murphy, L., 2012, Reading for understanding: How reading apprenticeship improves disciplinary learning in secondary and college classrooms, John Wiley, San Francisco, CA.

Schwartz, M., n.d., The learning and teaching office. Getting students to do their assigned readings, viewed 15 November 2017, from https://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/lt/resources/handouts/student_reading.pdf.

Scott, I., Yeld, N. & Hendry, J., 2007, Higher education monitor: A case for improving teaching and learning in South African higher education, Council on Higher Education, Pretoria.

Styan, J.B., 2014, 'The state of SA's tertiary education', Finweek 6(19), 10-15. [ Links ]

Taraban, R., Rynearson, K. & Kerr, M., 2000, 'College students' academic performance and self-reports of comprehension strategy use', Reading Psychology 21(4), 283-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/027027100750061930 [ Links ]

Van de Poel, K. & Van Dyk, T., 2014, 'Discipline-specific academic literacy and academic integration', in R. Wilkinson & M.L. Walsh (eds.), Integrating content and language in higher education: From theory to practice, pp. 162-179, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main.

Van Dyk, T., Van de Poel, K. & Van der Slik, F., 2013, 'Reading ability and academic acculturation: The case of South African students entering higher education', Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 42(1), 353-369. https://doi.org/10.5842/42-0-146 [ Links ]

Wingate, U., 2007, 'A framework for transition: Supporting "learning to learn" in higher education', Higher Education Quarterly 61(3), 391-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2007.00361.x [ Links ]

Woolley, G., 2011, Reading comprehension: Assisting children with learning difficulties, Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1174-7_1

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kristien Andrianatos

13132873@nwu.ac.za

Received: 15 Apr. 2019

Accepted: 07 Aug. 2019

Published: 30 Sept. 2019

1 . In this article, the term 'barriers' will be used to refer to some of the reasons why students struggle to read, as it figuratively stands in the way of students' reading development.

^rND^sAlexander^nP.A.^rND^sArcher^nA.^rND^sBerndt^nA.^rND^sPetzer^nD.J^rND^sWayland^nJ.P.^rND^sBernstein^nB^rND^sBharuthram^nS.^rND^sBharuthram^nS.^rND^sClarence^nS.^rND^sBoakye^nN^rND^sSommerville^nJ.^rND^sDebusho^nL.^rND^sButler^nG.^rND^sDel Principe^nA.^rND^sIhara^nR.^rND^sHaggis^nT^rND^sHallett^nF.^rND^sHoeft^nM.E.^rND^sHoward^nP.J.^rND^sGorzycki^nM.^rND^sDesa^nG.^rND^sAllen^nD.D.^rND^sJacobs^nC.^rND^sMacMillan^nM.^rND^sMcLoughlin^nK.^rND^sDwolatzky^nB.^rND^sMorreale^nS.P.^rND^sStaley^nC.M.^rND^sNel^nC.^rND^sDreyer^nC^rND^sKlopper^nM.^rND^sNiven^nP.M.^rND^sPretorius^nE.J.^rND^sPretorius^nE.J.^rND^sStyan^nJ.B.^rND^sTaraban^nR.^rND^sRynearson^nK.^rND^sKerr^nM.^rND^sVan Dyk^nT.^rND^sVan de Poel^nK.^rND^sVan der Slik^nF.^rND^sWingate^nU.^rND^1A01^nPatience^sDlamini^rND^1A02^nAyub^sSheik^rND^1A01^nPatience^sDlamini^rND^1A02^nAyub^sSheik^rND^1A01^nPatience^sDlamini^rND^1A02^nAyub^sSheikORIGINAL RESEARCH

Exploring teachers' instructional practices for literacy in English in Grade 1: A case study of two urban primary schools in the Shiselweni region of Eswatini (Swaziland)

Patience DlaminiI; Ayub SheikII

IDepartment of Instructional Design and Development, Institute of Distance Education, University of Eswatini, Manzini, Eswatini

IIDepartment of Language Education, Faculty of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Literacy education in the foundation phase is a global concern. Studies have shown that mastering literacy in the first three years of school ensured academic success and lack of it had negative effects academically, socially and economically. This research study sought to explore teachers' instructional practices for literacy in English in Grade 1 in the Shiselweni region of Eswatini.

OBJECTIVES: The objectives of the study were to establish what instructional practices teachers used in their literacy classrooms, why they used those instructional practices, and how they experienced the teaching of literacy in English in Grade 1.

METHOD: A qualitative case study design was followed where three teachers from two urban schools were purposively sampled and participated in semi-structured interviews and classroom observations. Focus group discussions with teachers who had experience teaching literacy in English in Grade 1 in each school were conducted, and document analysis was done. Vygotsky's sociocultural theory was used as a lens to understand teachers' instructional practices in literacy.

RESULTS: Data were analysed using thematic content analysis. The findings of the study showed that teachers' instructional practices reflected their lack of pedagogical knowledge for teaching literacy in English in the foundation phase. The study also found that the teachers' experiences were their rationale for their instructional practices.

CONCLUSION: The study showed that teacher resilience was important for teachers to thrive under trying school conditions; developing a positive attitude towards literacy teaching enabled teachers to develop strategies to improve literacy teaching and learning.

Keywords: English education; literacy; knowledge; primary schools; Swaziland; Eswatini.

Introduction

Studies have shown that in most African countries, learners' performance in literacy in English in the foundation phase remains poor regardless of efforts to mitigate the situation. A critical view is that developing strong literacy in the foundation phase equips the individual child for continuous learning (Lesaux 2013:3). In the long term, early development of literacy also plays its part in revitalising the economy and containing the scourge of unemployment; it further combats poverty, improves health and promotes social development (Chowdhury 1995). Researchers affirm the view that exposure to an early childhood programme boosts the cognitive and social development of a learner, attributes that are needed for successful schooling (Barnett 2011; Castro et al. 2011). However, in Swaziland - henceforth Eswatini, this is not happening on the ground, as a large number of preschool-age children continue to begin the first grade at school without this essential early childhood education experience. The effect of lack of early childhood education in Eswatini is evident through the high number of learners who continue to perform poorly in English literacy in the foundation phase, repeating foundation phase classes, especially Grade 1. The high repetition rate results in some learners dropping out of school without having mastered basic literacy in the English language, thereby exacerbating the gap between literate and illiterate youth in the region (Ndaruhutse 2008). Similarly, Eswatini is plagued with persistent high failure rates in Grade 1. As a consequence, learners drop out of school without basic literacy.

National reports show that the government of Eswatini has made education its priority since the inception of independence in 1968. However, little improvement has been seen in early childhood education which in an ideal education system should be a feeder to Grade 1. This is ascertained from the education reports in the country. For instance, the Eswatini (2015) 'Education for All' review report shows that less than 1% from the budget of the Ministry of Education and Training goes to early childhood education. This shows that government has little commitment to improving the situation in the foundation phase as the report also states that preschool education was not a prerequisite for children to enrol into Grade 1 (Government of Swaziland, 2015). The report further states that government was not responsible for training, engaging and remunerating early childhood education teachers, the very people who are responsible for laying a solid literacy foundation for learners.

In the researcher's practitioner experience as a subject advisor, the problems of literacy in English in the foundation phase in Eswatini could possibly emanate from poor instructional practices in the classroom. The problem is that, in Eswatini, there is a high failure rate in Grade 1. As a result, some learners spend more years at primary school than they should. The national education profile (2014) update shows that the repetition rate in Grade 1 in 2014 was at 17.9%, with a 29% dropout rate which could be a result of failure. A number of reasons account for the learners' failure. For example, the Southern and Eastern African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ 2013) showed that schools in the northern part still faced challenges as the level of achievement was lower than the expected standard due to lack of resources and poor socio-economic conditions. Eswatini fared better in the SACMEQ study, although the failure rate in Grade 1 remains high.

The problem is further aggravated by the fact that some learners reach Grade 3, not having mastered the basic skills of reading and writing, end up dropping out of school at this level. The 20.7% failure rate in Grade 3 is evidence of the problems the learners experience in literacy learning and is something that compromises their future academic achievement. This is counterproductive to the view that a strong literacy foundation is the cornerstone for education and economic development for all nations. Researchers agree that children who acquire strong foundational literacy in their early years are more likely to progress well academically than children who fail to develop literacy in the early years (Barnett 2011; Castro et al. 2011). It is in view of the value of the foundation phase in the education cycle that the researcher developed an interest in studying the teaching and learning of literacy in English in Grade 1. The reason for the focus on the Grade 1 class is that this is the level where most learners in Eswatini begin their education in public schools. The researcher wanted to understand what teachers do in their teaching of literacy in English classrooms, why they do what they do and how they experienced the teaching of literacy in English to the diverse Grade 1 learners.

Scientific value

Numerous studies have shown that Grade 1 teachers play an important role in shaping the foundation for early literacy skills for primary school learners (Clay 2005; Lenyai 2011; Pressley et al. 2001; Roskos, Tabors & Lenhart 2009). The teachers are the implementers of the curriculum and their expertise is central in the teaching-learning process as they are the ones to select the appropriate approaches, methods and techniques for fostering literacy in English (Lenyai 2011). In earlier research, Clay (2005) asserted that the first years of school are very important because this is when a solid foundation for literacy learning is laid. Verbal learning, central to an individual's academic life, is also developed at this level.

Roskos, Christie and Richgels (2003), in their study of the essentials of early literacy instruction, concluded that play has a significant role in children's education in the early years. Therefore, linking literacy and play is one of the most effective means to make literacy activities meaningful and enjoyable for children. They suggested eight strategies teachers could use with learners in the foundation phase and even at the intermediate and upper primary school levels. These include: rich teacher talk, storybook reading, phonological awareness activities, alphabet activities, support for emergent reading, shared book experience, and integrated, focused activities. It would be a good idea for Grade 1 teachers to initiate learning with play-based literacy activities that make learning enjoyable in the classroom.

A study done in Botswana (Republic of Botswana/United Nations 2004) shows that there was a high failure rate and level of school dropouts, especially in the remote parts of the country. This was partly attributed to poor supply of teaching and learning equipment by government, teachers' unreceptive attitudes to children from these isolated areas and the socio-economic conditions of the families of these children, as most were reported to travel long distances to and from school. These conditions altogether were not conducive for learning. Consequently, learners performed poorly and ended up dropping out of school in lower grades not having attained even basic literacy (Government of Swaziland, 2015). Lekoko and Maruatona (2005) observed that half of the student population who enrolled in Grade 1 dropped out before completing primary school thereby creating a large number of students who ended up enrolling for adult basic education in later years.

No systematic research has been undertaken to explore how Grade 1 teachers carry out their activities in teaching literacy in English in Eswatini. This study therefore explores teachers' instructional practices in literacy in English in Grade 1 focusing on two urban primary schools in the Shiselweni region of Eswatini.

Theoretical framework

This study was underpinned by Vygotsky's (1978) sociocultural theory. In linking the sociocultural theory to teaching and learning, Lantolf (2000) holds that the human mind develops by mediation. As a result, in the early years of school, learners largely depend on the teacher and other adults to support them with different tools in order to transform what they learn into personal knowledge they can internalise for future use. In essence, the teacher and other knowledgeable adults become mediators for learning. It is the responsibility of the teacher, therefore, to utilise the learners' sociocultural experiences as a frame of reference in learning literacy in the second language. Vygotsky was of the view that it is not practical to understand the cognitive development of an individual outside his or her social and cultural context; one's mental skills are considered to develop as a result of communication with other people in the social context. Daniels, Cole and Wertsch (2007) state that Vygotsky views the development of schoolgoing children to be a result of systematic school instruction. That being the case, the instructional practices of teachers are key in making sure that the learner develops systematic thinking and makes sense of their world, which they have already partially experienced. This perspective resonates with sociocultural scholars such as Freire and Macedo (2005) and Dyson (2013) who concur that children first read the world before they read the word. These scholars hold that learning literacy has to do with the relationship between the learners and the world. The adults are responsible for shaping the children's learning through different social activities. Vygotsky argues that the scientific concepts within the academic subjects are important for the schoolgoing child as they give the child an opportunity to use them consciously and intentionally. The teacher, therefore, is essential in unpacking these concepts in the academic subject for the students to develop as learners.

Research design and methods

This study followed a qualitative case study design. The researcher used the case study design to get rich, thick data of teachers' instructional practices in literacy in English in two urban schools in Nhlangano town, Eswatini. Another compelling reason for the choice of this design is that the researcher is able to study the subject in its natural setting, thereby getting a holistic picture of the case being studied from the point of view of the participants (Creswell 2009; Small & Uttal 2005; Yin 2003). The qualitative case study design therefore enabled the researcher to explore teachers' instructional practices from their settings in the schools and in their Grade 1 literacy English classrooms.

The two schools from which data were collected were located in Nhlangano, the administrative town of the Shiselweni region of Eswatini. It is important to mention that these two primary schools are government-owned mixed schools where both girls and boys are enrolled. The teachers are government employees, the curriculum followed is developed by the government, through the National Curriculum Centre, education of learners is paid for by government under the free primary education plan and the general infrastructure in the schools is owned by government. Though these schools are both in the urban area, the learners that were enrolled were mainly from the rural and peri-urban areas of the region. Most of these learners travelled to school by public transport as they stayed far from the schools. A very small number of learners stayed in town and walked to school. The Nhlangano town where this study is focused has only three urban schools; one was used to pilot the data collection instruments and the other two were used for the actual study.

Khoza (1999) noted a clear linkage between rural and urban poverty in Eswatini. He observed that the rural-urban migration of people in search of jobs and other income-enhancing opportunities transferred rural poverty into the urban areas, resulting in an increase of low-income peri-urban settlements which exacerbated urban poverty in Eswatini. Currently, the situation has not changed as Motsa and Morojele (2017) confirm in their recent study. Their study shows that in Eswatini, schoolgoing children undergo severe conditions due to the HIV pandemic and poverty as 24% of schoolgoing children were living with HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS 'AIDSinfor' 2017). This situation impacted negatively on various social services such as health facilities and schools. The available schools in the urban centre experienced high enrolment of children who lived in abject poverty in the peri-urban areas. Nhlangano town where this study is based is also affected by urban poverty. The children enrolled in the urban schools are victims of this socio-economic condition.

Three teachers were the main participants in this study. These teachers were interviewed and observed teaching Grade 1 literacy in English classrooms. The teachers were purposively sampled because they were currently teaching Grade 1 in the two sampled schools. They prepared schemes of work and lesson plans for the Grade 1 literacy in English lessons. All three teachers were Swazi females; one teacher from school A was responsible for teaching literacy in English in both Grade 1 classes in the school and two teachers from school B taught the two Grade 1 classes separately; each class had an average of 53 learners.

Additional data were collected from two groups of teachers who had experience teaching literacy in English Grade 1. These teachers participated in focus group discussions: four teachers from school A and six teachers from school B. Analysis of relevant documents used by teachers to plan for instruction was also done to understand teachers' instructional practices. The documents analysed were the English literacy syllabus, textbooks, teachers' guide and learners' books, schemes of work, lesson plans and tests given to learners.

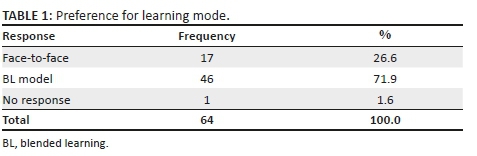

Teachers who currently taught literacy in English in Grade 1 at the two schools were interviewed and observed. Those who participated in the focus group discussions all had experience teaching literacy in English in Grade 1; they had lived experiences of the phenomenon (Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2011). Table 1 provides a summary of data collection instruments and participants.

Pseudonyms were used to ensure confidentiality and protection of the participants' identity. This was in line with the ethical standards in research as suggested by Johnson and Christensern (2000) who assert that the researcher should guard against any possible physical, emotional and psychological harm that may occur to the participant during the course of the study. For the purpose of data presentation, teachers who were interviewed and observed were referred to as Teacher 1, Teacher 2 and Teacher 3. Teacher 1 was from school A and Teacher 2 and Teacher 3 were from school B.

Data collection and analysis

This study was a qualitative case study, situated in the interpretive paradigm. Various data collection methods were used to gain a holistic understanding of the case. Semi-structured interviews, classroom observations, document analysis and focus group interviews were the main data collection instruments for this study. Interviews and focus group discussions were audio recorded and then transcribed at the end. Field notes were recorded and pictures taken for classroom observation. The transcripts were later sent to the interviewed teachers to check if they correctly captured and presented their views.

Analysis

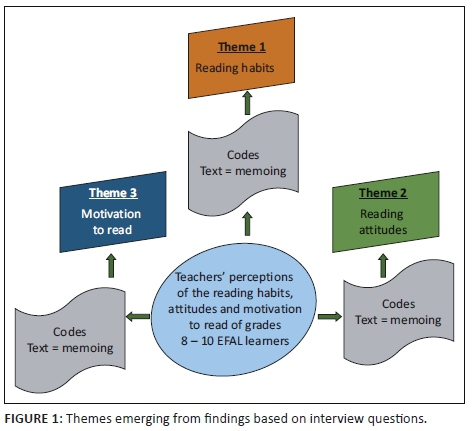

As this study was purely qualitative, the most appropriate data analysis method that the researcher followed was thematic content analysis. According to Krippendorff (2004:18), content analysis is a 'research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from text (or other meaningful matter) to the context of their use'. Data analysis began as soon as the data-gathering process commenced. This was done to create a coherent interpretation of the data (Maree 2007:111). This process began with the verbatim transcription of data gathered from the three Grade 1 teachers who were interviewed. The transcription was backed up by notes taken during the interviews. The transcripts were read thoroughly to identify key themes that emerged from the data, codes were given to the themes, and similar ideas were categorised under one theme for further analysis (Ary, Jacobs & Razavieh 2002; Cohen et al. 2011; Maree 2007). The aim was to make sense of what the data suggested about the phenomenon under study and teachers' instructional practices in literacy in English in Grade 1.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was issued by the University of KwaZulu-Natal after all consent letters were submitted to the relevant gatekeepers and participants. Ethical clearance number: HSS/0442/015D.

Results

The data that yielded the four major themes came from the interviews and observations of the three teachers who taught literacy in English in Grade 1. Data from focus group discussions and document analysis corroborated that data. The four major themes were: teacher navigation between half transmitter and half facilitator, rationale for teachers' instructional practices, teachers' experiences of teaching literacy in English, and teachers' ideas for improving literacy teaching and learning.

Theme 1

The first theme showed that teachers had a theoretical knowledge that instructional practices in literacy in English involved multiple activities that teachers did together with the learners to ensure that learning occurred. Those interviewed stated that the transmission role required teachers to tell learners what to do and how. On the other hand, the facilitator role required teachers to create opportunities for learners to discover things on their own and in the process acquire new knowledge.

'We do everything with Grade 1 leaners, there is a time when we tell learners everything to do and a time when we help them discover things for themselves, facilitating their learning.' (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'Some of these learners are very clear, they know a lot which you as a teacher do not think they would know.' (T2, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'When I ask a question, I first allow them to say what they know even if it is out of point, when they fail, it is then that I tell them the correct thing.' (T3, a Grade 1 teacher, female).

However, classroom observations showed that the teachers did not always use the learner-centred approach in their classrooms; they still dominated classroom activities and hardly created opportunities for learners to work together to discover information. This was contrary to the sociocultural theory that saw teachers as facilitators for learning through the use of the learners' sociocultural experiences (Vygotsky 1978).

Theme 2

The second theme revealed that the rationale for teachers instructional practices in the literacy classrooms was based on a number of factors, such as their pedagogic content knowledge in literacy, beliefs about the teaching and learning of literacy, in-service training, learner academic needs, curriculum standards, learner background (preschool and home background) and parental involvement. Interviews with the three teachers showed that they lacked clear understanding of what literacy in English entails; their definitions of literacy were general and not specific to what literacy is.

'Literacy is the learning and reading of English, the way they learn and understand the English and teachers should try by all means to help learners speak English.' (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'Literacy is more than understanding English and understanding writing, literacy is the correctness of the language and the rate at which the learner picks up the information the teacher gives.' (T2, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'Literacy is when you encourage learners to communicate in English to make them have a strong command of the language; they have to learn how to express themselves.' (T3, Grade 1 teacher, female)

The teachers also said that they lacked pedagogic content knowledge of foundation phase literacy education as pre-service training did not adequately equip them for teaching literacy to Grade 1 learners; as a result, they were not confident in their practices. There was no balance between their pedagogic content knowledge and classroom practices. The classroom practices were contrary to Shulman and Shulman's (2004) and Hashwesh's (2005) view that pedagogic content knowledge balances what teachers should know about the subject they teach (subject matter knowledge) and preparation of how the content should be taught (pedagogy). The teachers stated that what they did is what they had learned on the job:

I think the teaching of literacy must be something for the teacher who has the knowledge and the skills of teaching literacy with young learners. (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

Teacher 4 from the focus group corroborated this view:

'We find it very challenging to teach English literacy in Grade 1 because we don't have all the skills, sometimes we are not sure of what to do with these young learners because we were not trained to teach in the foundation phase.' (T4, Grade 3 teacher, male)

The interviews with the teachers also revealed that teacher belief has played an important role in the way they carried out their practices in literacy in the English classroom. Squires and Bliss (2004:756) state that all teachers bring to the classroom some level of belief that influences their decisions. The interviewed teachers and those who participated in the focus group interviews believed that teachers were role models in the classroom and learners unconsciously copied what they did. Consequently, there should be careful planning to eliminate errors:

'They copy what I do, young children do what you as a teacher do, even the way you speak; they would speak like you, even writing. If I have made a mistake, they copy the mistake as it is.' (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

Teacher 2 shared a similar view:

'In Grade 1 what you must know is that the children depend very much on the teacher. How you pronounce words, they will do exactly, if there is a mistake, they take it from the teacher.' (T2, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'If you make a mistake in a word, you have to correct it very fast because they just hold on to that.' (T3, Grade 1 teacher, female)

The finding also showed that to a large extent, what teachers did in class reflected their understanding of what literacy is and how it should be taught. They viewed themselves as the most important people to help learners learn English literacy.

Theme 3

The third theme that emerged was that of the different challenges experienced by the schools, learners and teachers.

Lack of mentoring and lack of teaching and learning resources made the teachers' experiences difficult:

'The first time I taught Grade 1, it was very difficult because I had no experience in teaching the lower grades, but I learnt a lot about the child. I did not know how they behaved and I had no one to help me on how to handle these young learners. The first year I was just confused, in the second year I started correcting myself, where I felt I wasn't sure of what I was doing.' (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'At first it was very challenging because I was fresh from college and no one helped me. The next year, it became better.' (T2, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'Since it is my first time, there are challenges, and no one is there to hold me by the hand but then, as I continue teaching, I find it easier by the day.' (T3, Grade 1 teacher, female)

The absence of mentoring for teachers in the teaching of literacy in English, especially in the foundation phase, corroborates the views of Hanushek (2009) who affirms that the quality of teachers is the key element in improving student performance. Mentoring of the teachers ensures the desired quality and capacity.

A school-related challenge was the lack of teaching and learning resources, and lack of time by teachers to prepare teaching resources due to heavy workloads resulting from high enrolment in the schools. Moreover, the schools have no proper library facilities:

'We know that we have to use relevant materials such as pictures because children understand better when they see pictures and other reference materials … but the problem is that we don't always find them.' (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'Sometimes you know that if I can have this resource or maybe share with other people the lesson could be effective, only to find that you don't have the time to visit some places where you can maybe get the material because we [are] always busy.' (T2, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'Even if you think of preparing something to support the learners, you cannot because of the work load; you have to do a lot of paper work in the classroom. Also, the enrolment is high and these children need a lot of patience.' (T3, Grade 1 teacher, female)

Teacher 4 from focus group B shared a similar view:

'We teachers need more time for our planning, and to be able to research on our work but we don't have enough time, sometimes you have to do your own research only to find that there is no time.' (T4, Grade 3 teacher, female)

'We do have library material but we don't have time because even if they go to the library, it must be the teacher who's teaching the languages to help these children because there is no one employed for that, and with so much work to do, we don't have that time.' (T6, Grade 2 teacher, female)

Learner-related challenges included lack of a common starting point due to poor management of early childhood education programmes in the schools, lack of environmental support for learning (parental support and community support), learners' lack of interest in reading, as well as linguistic and cultural diversity. Data from the focus group discussions and interviews with the three teachers showed that a major challenge teachers faced with Grade 1 learners in the participating schools was a lack of a common starting point for school. As a result, learners began school with different entry competences. The data showed that in Eswatini, preschools were still privately owned and not government sponsored and followed their own curriculum. Parents were not compelled to take their children to preschool; as a result, learners began school with varying degrees of competence with respect to language and literacy skills. This disparity in the learners' experiences when they begin school was a challenge for the teachers who had to complete a syllabus and ensured that learners mastered the different literacy skills.

One teacher from focus group A said:

'The main challenge I have encountered is that most of the pupils were learning English for the first time since some of them did not even go to preschool, you find that while you are teaching English, there are some things that you have to explain to them in SiSwati because some are just not following.' (T5, Grade 2 teacher, female)

The lack of early childhood education does not augur well for learners' education and scholars agree that early childhood education is critical in developing the child holistically, physically, socially, emotionally, cognitively and culturally for successful schooling to take place (Barnett 2011; Castro et al. 2011).

The findings of the research from focus group A showed that although the learners were in urban schools, they were mainly from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds and lacked necessary support from home and from the community. The teachers in the focus groups stated that most learners stayed in the townships with single parents who worked in the textile industries and never had the time to support learners in their school work. They left home very early in the morning and returned tired in the evening. Data from focus group A confirmed what Teacher 1 from school A had said and teachers agreed that, in cases like these, there was little support parents could offer to the learners, which hindered the pace at which learners mastered literacy skills. The teachers stated that parents rarely made voluntary visits to the schools to find out how their children were progressing and how they could assist them. Parents only visited the school when they were requested to do so and, when they came, they did not give themselves time to talk to the teacher to understand their children's challenges. One teacher from the focus group said:

'The parents only come to the school during the open day, they only need the report, they are only interested in their children's result, and they don't care about other things. When you talk to them, "please help us with your child" on this aspect, you could see that you are delaying them, they are rushing, that's the problem!' (T2, Grade 1 teacher, female)

Theme 4

Another theme that emerged was teacher initiatives to improve literacy learning. This theme was based on strategies the teachers used to counter challenges. Teachers in the case study schools had devised some strategies to counter some of the challenges they experienced in their teaching of literacy in English in Grade 1. These strategies include developing a positive attitude for the work, providing reading materials for their classes, organising internal workshops with other teachers and remediation. The findings showed that since teachers were the implementers of the curriculum, they had to devise strategies to counter the challenges, without which the teaching and learning of literacy in English could be a futile exercise. The teachers stated that developing love and appreciation for the different learners helped them to be patient with their inadequacies and to try by all means to help them learn. They had this to say:

'I love the subject; I get involved and use whatever I come across if I think that it will help my children understand because I love the subject.' (T1, Grade 1 teacher, female)

'I make sure that I motivate learners to love the subject and make them practise whatever I teach them; for example, practise speaking English when they are playing outside. I make sure that they use the language and encourage them to love it.' (T2, Grade 1, teacher, female)

'I try my best to be supportive, I bring all magazines I have just for them to page and look at the pictures. I also ask those who can to bring some old magazines from home.' (T3, Grade 1 teacher, female)

Classroom observation showed a box of old magazines and newspapers that Teacher 3 brought to her class for learners to page through and look at the pictures. They were even allowed to cut out pictures they liked and paste them in their exercise books.

Teacher 5 from focus group B said:

'As a teacher you need to be a role model to the learners. Give them the reason why they should speak in English rather than forcing them. I just use English every time so that they take it from me, and that has helped me over the years.' (T5, Grade 2 teacher, female)

Another important theme that emerged from the focus group discussions was possible ideas to improve literacy teaching and learning of literacy in Grade 1. The data showed that although there were a number of challenges teachers experienced in their teaching of literacy in English in Grade 1, teachers also had ideas they believed could improve the teaching and learning of literacy at this level. The ideas included the integration of information technology in the teaching and learning, use of mother tongue, teacher specialisation in the foundation phase and teacher-parent associations.

A view from the focus group discussion:

'The use of information technology tools can help, most of our children are advanced in the knowledge of these gadgets, and maybe even more than us because, at some homes they do have these resources but when they come to school, they find that we still don't have them.' (T4, Grade 3 teacher, male)

The teachers' idea of the use of information technology in literacy teaching and learning is supported by Furlog (2011) who argues that the use of information technology motivates learners, supports knowledge construction and creates a context for supporting learning by doing and conversing. Based on the teachers' view, supported by empirical research, the researcher concludes that an integration of IT in literacy learning, therefore, could benefit both learners and teachers to create a better classroom environment.

Discussion

Teacher navigation between half facilitator and half transmitter

The first theme revealed that teaching literacy in English at Grade 1 was a highly specialised activity that required teachers to play a role of being half transmitters of knowledge and also half facilitators of learning. The transmission role required teachers to tell learners what to do and how. On the other hand, the facilitator role required teachers to create opportunities for discovery learning. From this study, the transmission of knowledge was more dominant than the facilitation of learning. The teachers' practices were not clearly aligned to the sociocultural perspective that advocates for the social and cultural experiences of the learners to be at the centre of their learning, especially in the foundation phase. Moreover, they were not in line with the views of Sarigoz (2012:253) who holds that play-based techniques to teaching literacy to Grade 1 learners, such as games, songs, puzzles, crafts, stories and drama, were suitable to create a child-friendly language learning environment. Instead, teacher instructional practices showed that teachers did what worked for them in their classrooms without basing it on sociocultural theory. This also revealed their lack of the required expertise for teaching literacy in English in Grade 1.

In their instructional practices, teachers made an effort to motivate learners in their classrooms and displayed their works on the wall and constantly praised and clapped hands for learners who made an effort to respond to oral questions. From the researcher's observation, teachers were keen to support learners in their efforts to acquire literacy in English. The challenge was that their teaching approaches were not balanced and they placed more emphasis on explicit teaching and writing activities at the expense of creating a more enabling environment for literacy learning. The teachers' practices were not clearly aligned to the sociocultural perspective that advocates for the social and cultural experiences of the learners to be at the centre of their learning, especially at the foundation phase. The teachers' instructional practices were also contrary to the view of Uzuner et al. (2011) who argue that it is important at an elementary level to include a concise and balanced literacy system that has the advantage of increasing students' comprehension of literacy.

Rationale for teachers' instructional practices in Grade 1

Teachers had a wide-ranging rationale for their instructional practices in Grade 1 literacy. These included teacher pedagogic content knowledge in literacy, teacher beliefs about the teaching and learning of literacy, in-service training, learner academic needs, curriculum standards, and learner needs which include preschool and home background, learner developmental age and learner interest. The teachers were of the view that their knowledge about the subject of literacy in English was important in determining what they taught and how they taught, a view supported by Shulman and Shulman (2004) and Leong et al. (2015) who hold that pedagogic content knowledge balances what teachers should know about the subject they teach (subject matter knowledge) and preparation on how the content should be taught (pedagogy).

Teachers raised a concern that learners who enrolled in Grade 1 had no common introductory ground as some were from preschool and others were not. The study showed that the disparity of the learners who enrolled in these two urban schools was mainly caused by urban poverty in the region. The background showed that there was a high rate of rural-urban migration in Eswatini and this exacerbated poverty. Some learners who lived in the town and attended the two urban schools were actually from impoverished families and had no support from home. If it were not for the free primary education some of these learners would not be at school. The high cost of preschool education prevented most parents from enrolling their children for preschool education which caused the disparity in the learners who enrolled in Grade 1.

The study showed that the teachers' knowledge of the learners' needs was important in guiding the teachers' planning of lessons. This view is clearly articulated by Lyons and Pinnell (2001) who state that the most important concern teachers have is for their individual learners' strengths, habits, attitudes and needs. They are of the view that when teachers know their learners individually, it is easier for them to guide and support them in their literacy needs. Lyons and Pinnell write:

Knowing our students is critical to teaching literacy successfully, because they bring knowledge and experience to the literacy process. Recognizing what the students bring to reading and writing powers our instruction. The meaning and the pleasure of literacy resides within the individual. (p. 35)

Teachers' experiences of teaching literacy in Grade 1

The study showed that there are a number of issues that make up teachers' experiences of teaching literacy in English in Grade 1. A major conclusion that emanated from this study was that teachers faced a lot of challenges in the teaching of literacy in English at Grade 1 level and these challenges made their experiences unpleasant especially for new teachers. The lack of mentoring for teachers who taught Grade 1 literacy for the first time was frustrating. Also, having to deal with learners who came to Grade 1 with different entry competencies because there was no common starting point for all learners increased the teachers' challenges. However, the resilience that the teachers developed with time helped them to devise effective strategies that improved learners' achievement in literacy. These include development of a positive attitude, engaging learners in remedial work and organising internal workshops with other teachers. These mitigating measures helped improve the situation and made the teachers' experiences bearable. The study showed that a positive attitude was important for teachers to develop resilience in their work.

Strategies teachers used to counter the challenges

Teachers in the case study schools had devised some strategies to counter some of the challenges they experienced in their teaching of literacy in English in Grade 1. These strategies include developing a positive attitude for the work, providing reading materials for their classes, organising internal workshops with other teachers and remediation. The findings showed that since teachers were the implementers of the curriculum, they had to devise strategies to counter the challenges, without which the teaching and learning of literacy in English could be a futile exercise. The most critical aspect was to work on their attitudes; they stated that developing a positive attitude towards their work helped them to cope. The positive attitude enabled the teachers to make an effort to provide reading materials for the learners, provide remedial lessons for struggling learners, and also organise internal workshops among themselves. The idea of teachers' collaboration in the schools is supported by Wium and Louw (2011:86) in their work on the 'exploration of how foundation phase teachers facilitate language skills'. They assert that the development of a child involves an interdisciplinary field of knowledge that teachers bring to the profession.

Ideas to improve the teaching and learning of literacy in English in Grade 1

The study showed that regardless of the challenges teachers experienced in their teaching of literacy in English at Grade 1 level, they had ideas that they believed could improve the teaching and learning of literacy in Grade 1. These ideas included the integration of information technology in the teaching, use of mother tongue, teacher specialisation in the foundation phase and teacher-parent associations. The teachers were of the view that employing teachers who had specialised in foundation phase education could improve literacy teaching because these teachers would know which effective instructional practices to implement in order to meet varied learners' needs. Moreover, the teachers believed that the integration of information technology in the curriculum would benefit learners because children were fascinated by technology. The teachers' idea corroborated the views of Aubrey and Dahl (2008) who argue that the use of information technology motivates learners, supports knowledge construction and creates a context for supporting learning by doing and by conversing. Van Scoter (2008) also holds that the use of information technology with young children can help to support meaningful learning as it increases one's understanding of the world through communication, language, literacy and problem solving.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that teachers understand that Grade 1 is an important foundation phase level and teaching at this level requires specialised training. They acknowledged that they lacked the necessary expertise for effectively teaching literacy in English at this level. Consequently, there is a strong recommendation that government considers hiring teachers who are qualified to teach at the foundation phase for effective literacy in English instruction. It is believed that teachers who are qualified in foundation phase education would be able to meet the diverse needs of the learners. The study also showed that there are various factors that explain teachers' instructional practices: teacher-related, learner-related and school-related factors. Altogether, these factors make up experiences of the teachers. As implementers of the curriculum, teachers had to deal with these challenges, most of which they had no control over. The most glaring challenge was that learners who enrolled in Grade 1 did not have a common starting ground as there was still no Grade 0 in the public schools.

Recommendations

There is a strong recommendation that government introduces Grade 0 in the schools to bridge the gap for learners who enrol for Grade 1. It might also be essential for the curriculum designers to integrate technology-based literacy in English programmes in the foundation phase to improve literacy learning.

Acknowledgements

The teachers of the two primary schools that participated in this study. They provided useful data; without them, this study would not have been possible.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

P.D. is the one behind this idea and A.S. guided her as she did this work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Ary, D., Jacobs, L.C., & Razavieh, A., 2002, Qualitative research. Introduction to research in education, 4th edn., vol. 6, Wadsworth Group, New York, NY.

Aubrey, C. & Dahl, S., 2008, A review of the evidence on the use of ICT in the Early Years Foundation Stage.

Barnett, W.S., 2011, 'Effectiveness of early educational intervention', Science 333(6045), 975-978. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204534 [ Links ]

Castro, D.C., Páez, M.M., Dickinson, D.K. & Frede, E., 2011, 'Promoting language and literacy in young dual language learners: Research, practice, and policy', Child Development Perspectives 5(1), 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/.1750-8606.2010.00142.x [ Links ]

Chowdhury, K.P., 1995, Literacy and primary education, Working papers, World Bank, Human Resource Development and Operations Policy, New York.

Clay, M.M., 2005, Literacy lessons designed for individuals: Why? when? and how?, Heinemann Educational Books, Portsmouth.

Cohen, L.M. & Manion, L. & Morrison, K., 2011, Research methods in education, Routledge, Abingdon.

Creswell, J.W., 2009, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches, 3rd edn., Sage, London.

Daniels, H., Cole, M. & Wertsch, J.V., 2007, The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Dyson, A.H., 2013, Rewriting the basics: Literacy learning in children's cultures, Teachers College Press, New York, NY.

Freire, P. & Macedo, D., 2005, Literacy: Reading the word and the world, Routledge, London.

Furlog, K., 2011, 'Small technologies, big change: Rethinking infrastructure through STS and Geography', Progress in Human Geography 35(4), 460-482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510380488 [ Links ]

Hanushek, E.A., 2009, 'Building on no child left behind', Science 326(5954), 802-803. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177458 [ Links ]

Hashwesh, M.Z., 2005, 'Teacher pedagogical constructions: A reconfiguration of pedagogical content knowledge', Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 11(3), 273-292. [ Links ]

Johnson, B. & Christensen, L., 2000, Educational research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches, Allyn & Bacon, Washington, DC.

Khoza, B., 1999, 'Swaziland urban poverty: Namibian country paper on mainstreaming urban poverty reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa', in M. Gachocho (ed.), Urban poverty in Africa: Selected countries experiences, pp. 105-113, United Nations Centre for Human Settlement, Nairobi.

Krippendorff, K., 2004, 'Reliability in content analysis', Human Communication Research 30(3), 411-433. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/30.3.411 [ Links ]

Lantolf, J.P., 2000, 'Second language learning as a mediated process', Language Teaching 33(2), 79-96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800015329 [ Links ]

Lekoko, R.A. & Marautona, T., 2005, 'Opportunities and challenges of widening access to education: Adult education in Botswana', viewed from http://www.unesco.unesco.org/images/100141/0001460.

Lenyai, E., 2011, 'First additional language teaching in the foundation phase of schools in disadvantaged areas', South African Journal of Childhood Education (SAJCE) 1(1), 14-36. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v1i1.76 [ Links ]

Leong, K.E., Meng, C.C., Rahim, A. & Syrene, S., 2015, 'Understanding Malaysian pre-service teachers mathematical content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge', Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education 11(2), 363-370. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2015.1346a [ Links ]

Lesaux, N.K., 2013, 'PreK-3rd: Getting literacy instruction right', Foundation for Child Development 9, 3-18. [ Links ]

Lyons, C.A. & Pinnell, G.S., 2001, Systems for change in literacy education: A guide to professional development, Heinemann, Westport, CT.

Maree, K., 2007, First steps in research, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Motsa, N.D. & Morojele, P.J., 2017, 'Vulnerable children speak out: Voices from one rural school in Swaziland', Gender and Behaviour 15(1), 8085-8104. [ Links ]

Ndaruhutse, S., 2008, Grade repetition in primary schools in sub-Saharan Africa: An evidence base for change, CfBT Education Trust, Reading.