Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa

versão On-line ISSN 2307-6267

versão impressa ISSN 2311-1771

JSAA vol.11 no.2 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i2.4915

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Graduate transitions in Africa: Understanding strategies of livelihood generation for universities to better support students

La transition des diplomas en Afrique : Comprendre les strategies de creation de moyens de subsistance pour que les universités soutiennent mieux les étudiants

Andrea JuanI; Adam CooperII; Vuyiswa MathamboIII; Nozuko LawanaIV; Nokheth MhlangaV; James Otieno JowiVI

ISenior Research Specialist: Equitable Education and Economies, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban; Honorary Research Fellow: School of Law, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. Email: Ajuan@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-6399-4001

IISenior Research Specialist: Equitable Education and Economies, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa, and Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town and XXXXX: Education Policy Studies Department, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. Email: Acooper@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0003-3605-2032

IIISenior Manager: Research, Equitable Education and Economies, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa. Email: vmathambo@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-0638-0708

IVData Analyst: Equitable Education and Economies, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa. Email: nlawana@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0003-0027-4725

VSenior Researcher: Equitable Education and Economies, Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: Nmhlanga@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0009-0001-3286-4482

VIPrincipal Education Officer, Secretariat: East African Community, Arusha, Tanzania; Executive Founding Director: African Network for Internationalization of Education (ANIE). Email: jowij@anienetwork.org . ORCid: 0009-0000-9589-8826

ABSTRACT

Graduate transitions and pathways do not naturally involve moving smoothly or sequentially from education into the world of work. Instead university graduates move through employment, entrepreneurship, unemployment and continued further education as they generate livelihoods. For African universities to be student-centred, with a focus on student development and success, the nature of these livelihood pathways must be examined in order to provide appropriate and relevant training and transition support. This article uses quantitative and qualitative data from African graduates who received a scholarship to complete their degrees at 21 universities (nine in Africa and 12 from other countries). Their post-graduation pathways are mapped and explored to determine how graduates generate livelihoods. The findings show that a minority of African graduates move smoothly from education into employment, and that for the majority, pathways are multidimensional and complex. While some move into the world of work with ease, most develop portfolios of income. By developing initiatives based on these findings, universities can help graduates navigate the challenges of income diversification, provide them with the necessary skills and resources, and foster a supportive ecosystem that encourages entrepreneurial thinking and diversified career paths.

Keywords: Graduate transitions, livelihood transitions, student transitions, transition support, engaged university, labour market pathways

RÉSUMÉ

La transition et le cheminement des diplomas ne consistent pas á passer naturellement et de manière fluide ou sequentielle des études au monde du travail. Au contraire, les diplomas d'universités peuvent traverser des périodes d'emploi, d'entreprenariat, de chomage et de formation continue, tout en générant des moyens de subsistance. Pour que les universités africaines soient centrées sur l'étudiant, et qu'elles mettent l'accent sur son développement et sa réussite, la nature de ces parcours de vie doit être examinée afin de fournir une formation et un soutien adaptés et adéquats au cours desdits parcours. Cet article se base sur des données quantitatives et qualitatives concernant des étudiants africains qui ont recu une bourse pour poursuivre leurs études et obtenir un diplome dans 21 universités (neuf en Afrique et 12 dans d'autres pays). Leurs parcours après l'obtention du diplome ont été cartographiés et analysés pour déterminer comment les diplomés génèrent des moyens de subsistance. Les résultats montrent qu'une minorité de diplomés africains passent aisément de leurs études á l'emploi, et que pour la majorité d'entre eux, les parcours sont multidimensionnels et complexes. Alors que certains s'insèrent facilement dans le monde du travail, la plupart développent des activités génératrices de revenus. Les universités peuvent aider les diplomés á relever les défis de la diversification des sources de revenus en développant des initiatives basées sur ces conclusions, en fournissant aux étudiants les compétences et les ressources nécessaires et en favorisant un écosystème propice á l'esprit d'entreprise et á la diversification des parcours professionnels.

Mots-clés: Transitions des diplômés, transitions de subsistance, transitions des étudiants, soutien á la transition, université engagée, parcours sur le marché du travail

Introduction

The African continent presents a complex landscape of challenges, encompassing issues like poverty, discrimination, poor educational achievement, and limited employment prospects (Cerf, 2018). Generalising about the prevalence of these challenges can be limiting, but making comparisons within and beyond the continent can provide valuable insights into the post-university experiences of graduates.

Notably, in Africa, the youth population, defined as individuals aged 15-24, constitutes more than a third of the working-age population, in contrast to the global figure of less than a quarter (International Labour Organisation, 2020). This demographic 'youth bulge' has led to an abundant labour force supply, intensifying competition for job opportunities in a challenging job market (Haider, 2016). Barriers to employment for African youth include unstable or shrinking economies; neglect of employment as a core component of the development agenda; employer perceptions, lack of entry-level jobs; inadequate education, skills, and work experience; limited labour market experience, weak networking, a lack of social capital; limited financial resources to effectively pursue employment opportunities and digitisation (Baah-Boateng, 2014). The lack of available and desirable employment therefore means that African youth, including some graduates, are forced to make a living through improvised forms of survivalism rather than secure wage work (Honwana, 2014; Thieme, 2018).

This situation is common in Africa and the Global South more broadly, as youth livelihoods are frequently characterised by precarity, informality, waiting, hustling, improvisation, survivalism and kukiya-kiya (a Shona term translating to 'like a key unpicking a lock' denoting survival strategies) (Kabonga, 2020; Thieme, 2018).

While two-thirds of non-agricultural workers in Africa earn a living in the informal sector and rates of graduate unemployment are certainly increasing, what is also clear is that intersecting processes of globalization, economic restructuring, diversification and informalisation have blurred the lines between formal and informal, skilled and unskilled work (Meagher et al., 2016). This has functioned to create new categories of labourers, including graduate micro-entrepreneurs, formal firms employing informal workers, and instances of modern bonded labour, with some scholars saying that binaries like formal-informal do not help in understanding how labour is being transformed under globalization (Meagher et al., 2016). What is clear is that graduate paths are full of continuities and discontinuities (Wood, 2017) over periods spanning several years, which have "u-turns", "detours", and "zigzags" (Schoon & Lyons-Amos, 2016, p. 14). In these pathways graduates may continue their studies, find employment, experience un-or underemployment, start businesses, or travel.

Youth in Africa regularly rely on innovative forms of improvisation, characterised as "the hustle" by Thieme (2018). They draw extensively on opportunistic practices that lie beyond formal institutional support. One way the pathways model has been adapted can be seen in the work of Schoon and Lyons-Amos (2016) who recognised the nonlinearity of youth transitions in the diverse pathways that they take into adulthood. Using data from two five-year cohorts born in the 1980s in the United Kingdom (UK), Schoon and Lyons-Amos (2016) identify five main pathways young people take out of school: continuous studies, finding employment straight after school and staying in it; studying after school and then moving into employment; long periods of unemployment; and long periods of economic inactivity (Schoon & Lyons-Amos, 2016). This diverse pathway framework (albeit not this particular model, which is specific to the UK context) has been validated in urban Bulawayo (Mhazo & Thebe, 2020), in peri-urban Cape Town (Webb, 2021), in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa (Rogan & Reynolds, 2016); in rural Kenya (Mwaura, 2017) and across a range of developing country contexts (Juárez & Gayet, 2014). It is an important contribution to the literature because it shows how those grouped together at a certain point (up to lower secondary school in this case) branch off into different types of life courses.

In the Global South, entrepreneurship tends to be promoted as a panacea for poverty and youth unemployment (Ngwenya & Mashau, 2019). In the literature, a distinction tends to be made between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs (Bayart & Saleilles, 2019; Fairlie & Fossen, 2017). Necessity entrepreneurs are usually driven by the need for economic survival resulting from unemployment, while opportunity entrepreneurs identify and seize business opportunities (Fairlie & Fossen, 2017). In addition, a new category found recently in the literature is that of programme-induced entrepreneurs. These are entrepreneurs who are inspired by programmes that offer entrepreneurship training and/or start-up funds (Mgumia, 2017). Regardless of the reason for starting a business, more needs to be known about how universities can better prepare students and graduates for future entrepreneurial activities.

In addition to the sheer plurality and variety of livelihood strategies people pursue, a second reality is the multiplicity and simultaneity of livelihood-making approaches.

People rely on several strategies across their lifetimes, while many pursue multiple strategies at the same time or rapidly jump between activities on a day-to-day basis (Kangondo et al., 2023). Capturing both the dissimilarity and interrelatedness of livelihood strategies is therefore imperative.

This article heeds the call by Cooper et al. (2019) to situate youth studies in the Global South. It problematises the transitions paradigm by becoming 'entangled in local realities' across Africa, in the belief that studying "contexts where youth have had to adapt, hustle and survive in precarious conditions for an extended period of time might demonstrate something unique about the human condition" (Cooper et al., 2019, p. 41).

Given this context, it is crucial for African universities to prepare students and support graduates to navigate the realities of generating livelihoods. The type of support offered must be informed by evidence. To this end, this article extends the current body of literature by using qualitative and quantitative panel data from graduates situated in a number of countries to answer the following research questions:

1. What pathways do young African graduates take to generate livelihoods?

2. How do these graduates generate livelihoods?

Understanding the post-university transitions of graduates is essential for universities to fulfil their educational missions, support their students, and adapt to the evolving needs of society. It contributes to enabling universities to remain relevant, effective, and responsive to the challenges and opportunities faced by their alumni.

Drawing on the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework and notions of navigational capacity as conceptual frameworks, qualitive and quantitative data from a larger study is analysed to answer these questions. Using the findings, we propose lessons that universities can employ to inform appropriate graduate support interventions.

Conceptual framework

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework is a conceptual framework that provides a holistic approach to understanding and analysing the various factors that influence people's livelihoods, particularly in the context of poverty reduction and sustainable development (Natarajan et al., 2022). The framework recognises that people's livelihoods are influenced by a complex web of interconnected factors, including social, economic, environmental, and institutional dimensions (Tabares et al., 2022). It seeks to understand the interrelationships among these dimensions and their impact on people's well-being and ability to sustain a decent standard of living over time. Key components of this framework are the use of assets or capitals and devising livelihood strategies. Assets refer to the resources and capabilities that individuals and households possess, which can be classified into five categories: natural, physical, human, financial, and social. Assets form the basis for people's livelihood strategies and their ability to cope with shocks and stresses (Tabares et al., 2022). Livelihood strategies are the diverse activities and choices people make to earn a living and sustain their livelihoods.

Livelihood strategies can include agricultural activities, wage labour, self-employment, migration, and access to social safety nets (Alobo Loison, 2015).

The notion of navigational capacities usefully illuminates how people negotiate their social contexts in order to generate livelihoods, with navigators and their environments symbiotically entwined, challenging individualistic interpretations of how young people overcome adversity as a component of their evolving environments (Appadurai, 2004; Swartz, 2021). The social notion of a capacity - unlike a capability, which refers to the individual repertoire of actions people perform - refers to future-orientated abilities and dispositions that are used in relation to others and which may be deployed for social change (Swartz, 2021). Navigational capacities are forged in context, through practices, pathways, and future-orientated aspirations, acknowledging that young people in adversity possess the potential to change their evolving environments (Swartz, 2021). Thus, livelihood is a multi-dimensional concept, stemming from the capacities people have, what people do and what they accomplish by doing it.

Methodology

The data for this article were taken from a large 5-year study called The Imprint of Education. The study, conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council, is in its fourth year. Quantitative and qualitative data are used to answer the research questions.

The quantitative data are from graduates who were born in Africa (N=544), and who studied at 21 universities (nine in Africa and 12 from other countries). These graduates completed their studies, funded by scholarships, between 2017 and 2020. Most of the graduates (78%) lived in an African country (18 countries in total), whilst the rest lived outside the continent. Respondents were surveyed in 2020 and again in 2022. Data were collected through call centres and online platforms. The data collection company had call centres in all countries of interest. This ensured that data collectors spoke the local language(s) and had local knowledge to enable us to capture the respondents' answers faithfully. The questions from the questionnaire relevant to this article regarded the labour market positions that respondents occupied. For each labour market position, further questions were asked in order to drill down into and examine the nature of it.

The panel data collected provide information on education and labour market pathways and the factors that shape these pathways. Descriptive and transition matrix analysis was conducted using Stata software (version 17). Markov Chain transition matrices were used to explore pathways and transitions by determining the proportion of individuals who moved from one state of economic activity into another state or out of it in the following period (Zannella et al., 2019). Panel data from the 2020 and 2022 surveys was used to create transition matrices. Each transition matric cell represents a probability where:

Where pij is the probability of respondents who moved from initial economic status i into a final economic status j for I =1..N and j =1,....., N. The term nij is the number of respondents who were in the economic status i and moved to economic status j between period t and t+1 and n is the number of respondents who were in state i in period t. A categorical variable for economic activities was constructed from four dummy variables (paid employment, studying, unemployed, business ownership). The 'unemployed' are those who are not in employment, not studying, not in entrepreneurship but looking for a job.

Qualitative data were obtained from individual in-depth interviews with graduates from the same institutions as the quantitative sample. Across the years, 122 were interviewed in 2020, 117 in 2021 and 106 in 2022. These interviewees also participated in the quantitative survey. Interviewees were asked about their lives and livelihoods.

Clarke and Braun's (2013) thematic data analysis process was followed to analyse the interview transcripts. This process provided a structured and systematic approach to qualitative data analysis, helping researchers uncover meaningful insights from their data and ensuring the rigour and transparency of their research findings. The analysis was conducted by a group of eight researchers under the direction of the co-principal investigator of the study. The process involved researchers immersing themselves in the data by reading and re-reading the collected material to become familiar with the content, identifying key themes and patterns that emerged. Next the transcripts were coded using Atlas.ti (version 8) software, which involves labelling or categorising segments of data based on content. Building on the initial codes, broader themes or patterns within the data were identified. These themes were reviewed, refined and defined, providing clear and concise descriptions of each theme, supported by relevant examples from the data. An anonymised report, using pseudonyms and country of residence as identifiers for interviewees, was generated for each theme.

Ethical clearance for the larger study was obtained through the Human Sciences Research Council's Research Ethics Committee, protocol number REC 6/19/06/19.

Limitation

A limitation of this study is that the sample of graduates is small and cannot be generalised to the population of graduates or scholarship recipients in Africa. The findings of this study are, rather, indicative of the African graduate experience. However, the use of qualitative and quantitative panel data provides the opportunity to explore graduate transitions broadly and deeply, across three years, on a cross-country scale, whereas other studies generally only use one type of methodology.

Findings

The findings are divided into two main sections, each of which answers one of the research questions.

What pathways do young African graduates take to generate livelihoods?

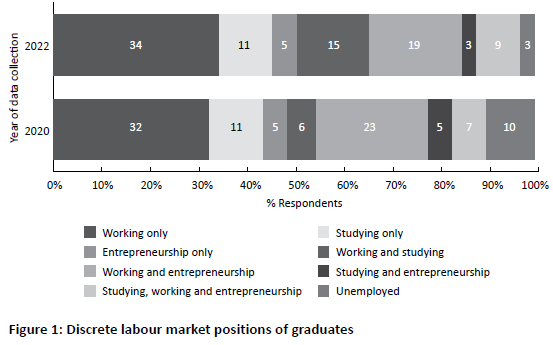

The labour market positions of the respondents were disaggregated into discrete categories to determine what they were doing in 2020 and 2022. Figure 1 illustrates that most respondents occupied a single position across the years (working only, studying only, entrepreneur only or unemployed). However, the ability of some young people to act by taking opportunities for livelihood generation is evident as a combined 41% in 2020 and 46% in 2022 occupied more than one position. Across the data collection points, about a fifth of the respondents supplemented income from employment with entrepreneurship activities.

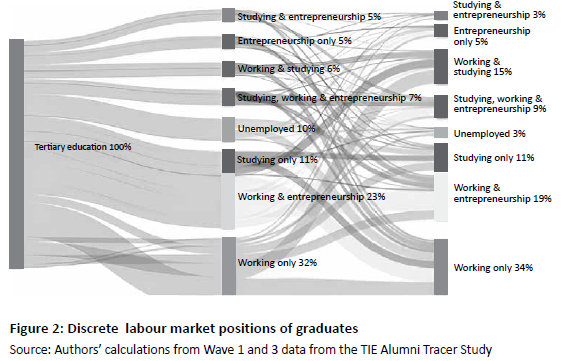

Examining the labour market positions in Figure 1 does not provide a full picture of graduate paths. The movements between these discrete position must also be explored. This was done through a transitions matrix analysis of the data. The results of the analysis are illustrated in Figure 2. Using the results, we mapped how the graduates moved (or did not move) from one discrete labour market position to another. The thickness of the bars in the diagrams below is proportional to the number of respondents who followed a particular pathway.

Figure 1 illustrates that while a third of the respondents in the survey were solely working in 2020 and 2022, only 16% of the total sample moved smoothly from tertiary education into a job and remained in employment (illustrated by the green band across the bottom of the graph). Among graduates who were exclusively employed in 2020, about a third continued working while also pursuing further studies or engaging in entrepreneurial ventures. A smaller portion of graduates opted for full-time studies, entrepreneurship, and 11% of those who were solely employed in 2020 reported unemployment in 2022.

The graduates in this study were engaged in entrepreneurial activities as part of broader livelihood strategies, under which multiple income streams were sourced while education activities also were undertaken. In 2022, more than a third of the graduates continued to work while simultaneously running their own business ventures. Among graduates who were employed and engaged in business ventures, some reported simultaneously studying, working, and being entrepreneurs in 2022. Half of the graduates who had not secured employment after graduating were now actively employed, with some having embarked on entrepreneurial ventures, while others had resumed their studies. Remarkably, only a few graduates remained without employment in 2022.

How do these graduates generate livelihoods?

Four livelihood generating strategies emerged from the data: having multiple streams of income, self-generated income, further education as an income source and getting a foot in the door. These are discussed in turn.

Multiple streams of income

While the survey questions on the nature of employment were on the main job1graduates had, it did ask how many jobs employed respondents had. In 2020 88% of respondents had one job only, this dropped slightly to 84% in 2022, meaning that three in 20 graduates hold multiple jobs. A quarter of those who were employed, had full-time appointments. Indicating a need or opportunity for other income generating opportunities.

Having a minimum of two significant sources of income and an educational activity characterised 21 graduates interviewed in the qualitative component of this study. Common income streams in this category included those who have a passion for farming and have managed to cultivate livestock and crops in rural areas alongside income generation through wage labour. For others this included side businesses that they started by selling a range of commodities or an NGO/social enterprise that they pursue for philanthropical purposes, but which also has material benefits. Some described multiple income streams as part of an ongoing approach to livelihood generation:

...They (employer) always encourage us to go back to school and upgrade and so on ... I think I've grown in terms of my projects, even in my job. I'm also going back to school very soon, but I will just be doing it through online school, but I'm just going to grow in terms of my enterprises, my projects at home, my family is growing. Yes, and my experience at work as well, we are growing. (Ezra, Uganda, 2022)

Ezra described his "enterprises and projects at home" forming part of an overall life strategy that included formal salaried work, operating alongside continually returning to improve his educational qualifications, as well as family responsibilities. Rather than a linear pathway from education into the world of work, Ezra described a pathway with multiple components intersecting simultaneously, part of a lifelong journey that develops on many fronts and in different contexts. A number of graduates mentioned rural, agricultural ventures as integral to their multiple income streams:

I am farming food. Maize, potatoes, tomatoes. I'm doing that, and also thanks to [my scholarship], my pocket money during school, I saved it all up and I bought myself a piece of land. (Jemima, Uganda, 2022)

Some interviewees diligently and frugally saved their stipend during their studies or their salaries after graduation, acquiring land that enabled them to grow, produce and sometimes keep livestock. These kinds of ventures found varying levels of success. For some, side-hustles contributed to helping support family in their livelihood endeavours:

I managed to save and get myself a piece of land which I hope, I plan to build a house there. For now, I'm building a house for my dad which is good. So, there is progress. (Lucia, Uganda, 2022)

Purchasing land was one way graduates demonstrated their gratitude to kin for helping to raise them, but it also enabled graduates to express their successful transition into adulthood. Lucia described this as "progress" above, demonstrating how this act of personal success symbolised development along her pathway. For others, the act of acquiring the asset of land and building a house demonstrated forms of personhood:

. after I got a job, I got a salary bump and sometimes you need to invest in something. I bought some land I need to build a house in the village. Here in Kenya,... if you don't have a house in the village, you are not a person. (Solomon, Kenya, 2022)

Solomon described purchasing land as enhancing his sense of identity and connectedness to family and friends, who formed part of his personal history. In periods of crisis, like during the COVID-19 pandemic, people like Solomon frequently returned to their rural base and resorted to subsistence living, a form of insurance in times of need. Others expressed that they intended to retire on these plots of purchased land, illustrating how this strategy formed part of social insurance in contexts where state-provided security, like healthcare and pensions, is limited. Some graduates preferred using urban or online ventures to generate multiple income-streams:

I want to ... build an income stream that is outside my normal job ... I started trading in stocks. (Joseph, Diaspora, 2022)

I'm doing bags online because I want to have a store in the city Side hustle. [I sell] Mostly on WhatsApp I have my middle person, because I go downtown, someone who can sell to me at a relatively low price. (Judith, Uganda, 2022)

Joseph and Judith mentioned investing in the stock market or commodities like handbags, activities that offer different kinds of risks and require other capitals in comparison to the rural ventures mentioned previously. For Judith, her networks and social capital, including socialisation in middle-class tastes and fashions, enabled her to purchase goods wholesale from someone in a local market and sell them in a different market online. One alumnus opened a game shop after he lost his job due to the pandemic, describing it in the following way:

I was able to raise my first capital to start a shop. So that's where I started the shop from, it came from my interest of movies, I actually love. And then it's IT related because everything there is more of engineering, and I took computer engineering in my undergraduate so everything I was doing at the shop is all related to my degree. So, it's more of my hobby, it was work, but more of a hobby because I love movies, I like interacting with IT stuff. (Archie, Kenya, 2022)

Archie's shop provided a recreational space for young people to play computer games and it doubled up as an internet café where he gave youth career advice and helped elderly people access documentation needed to secure government assistance. He was able to integrate his training as a computer engineer into a viable business venture that combined work with his interests, while also giving back to his community through service.

Therefore, many graduates worked in a salaried position, studied on the side and were involved in rural or urban forms of income generation to buttress their income, support kin and establish forms of social security for themselves for the future.

Furthering education as an income source

Scholarships act as a means of accessing education opportunities but also as a livelihood. While in both years of data collection, two thirds of graduates in the study relied on their jobs as their main sources of income, 14% in 2020 and 13% in 2022 relied on scholarships. Some of the interviewed graduates have pursued two or three master's degrees to access an income or have indicated that they wished to pursue a PhD because of material benefits. The pressure of supporting families means that some graduates look to the education sector, postgraduate degrees in particular, to generate income and provide for their families. Salma used her educational path to secure income abroad:

My plan for the next six years ... is well laid out... finish my Masters this year. Work for eight months. Then I will do a PhD for four years, then a post- doc for two years, so at least I'll have that. (Salma, Diaspora, 2021)

The theory of navigational capacities shows how people negotiate multiple, connected social contexts (Appadurai, 2004; Swartz, 2021). In this case, navigation involves creating symbiotically entwined environments to overcome adversity through using the most potent capitals in these young people's armoury, namely their academic capabilities.

Self-generated income

Respondents engaged in entrepreneurial activities as part of broader livelihood strategies, under which multiple income streams were sourced while education activities also were undertaken. Figure 1 showed that while the proportion of those who relied on their own business for income solely was small (about 5% in both years), about a fifth of graduates supplemented their employment with a business. This seems to point to the livelihood opportunities afforded to graduates by access to tertiary education, both in terms of formal employment and starting a business.

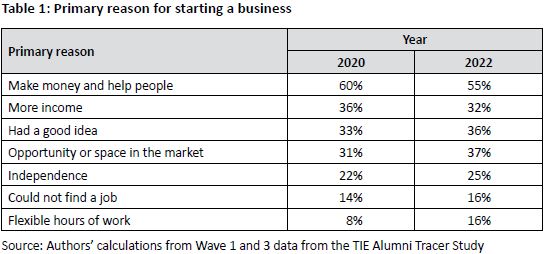

Across the years of data collection, most graduates who had businesses cited the need to make money and help people as having driven them to begin their businesses (Table 1). Second was the desire to have additional income.

What Table 1 also shows is the nuanced nature of graduate journeys into entrepreneurship which included necessity, opportunity, and intentionality. For some the need to make money and help people were key drivers; for others seeing an opportunity in the market or wanting additional income drew them to begin their own businesses. Interviewee statements illustrate their different routes into entrepreneurship.

... I wanted to set up the yoghurt manufacturing company, aside from its potential to sell, [was] its potential to employ most of the young people in my locality, in my community. (Pedro, Ghana, 2020)

Table 1 demonstrates the overlaps in the drivers of entrepreneurship. For instance, entrepreneurship training and resources provided by the scholarship fund enabled graduates to address immediate challenges in their lives and/or communities, thus responding from a point of necessity. Prioritising family obligation is a sentiment that was expressed by graduates in in-depth interviews:

You have a business somewhere... you have a side hustle, but I have like two or three businesses running, run by my sisters. (Sabrina, Uganda, 2021)

Furthermore, these opportunities and resources encouraged Alumni to explore entrepreneurship as a possible livelihood pathway with some making a success of these opportunities during and after university.

A foot in the door

Many tertiary graduates are underemployed, either due to their contracts being temporary, short-term, or part-time. Some (34% of those employed in 2020 and 30% in 2022) are employed in positions incommensurate with their qualifications or they have been forced to take up positions in a field or sector not of their choosing. For some this is a result of their age or life stage, finding work in the non-governmental organisation sector after the completion of their undergraduate studies. Many who follow this route initially access an internship with a stipend, positions which may become less "under" employed as they prove themselves and demonstrate their abilities. Of the 76 graduates interviewed in 2021 who were in paid employment, most felt that their jobs were dignified and fulfilling. A few felt that their jobs were not completely dignified and fulfilling or just one of the two. Some interviewees felt that while not completely dignified and fulfilling, their current jobs were a steppingstone where they could "build capacity and skills" to more dignified and fulfilling work (Godfrey, Uganda, 2021).

A strategy was observed through graduates who found work initially on a stipend or part-time basis and were initially underemployed. They would go back and complete micro-credentials while working. Education intended to assist their work in monitoring and evaluation project management or other areas. Some would then get promoted. For others, underemployment was not age-related and was due to the limited number of high-quality formal jobs in their particular contexts.

Discussion and conclusion

Drawing from the findings, we can conclude that the pathways graduates take after completing their studies are multidimensional and complex. In addition, graduates generate livelihoods through having multiple sources of income, furthering their education, self-generation and using underemployment as a means to securing well-paying employment later. While many graduates transitioned into the world of work, few had realized their aspirations in this sphere, meaning that they needed to continually cultivate agency to find their way along non-linear pathways that are made and remade. This form of agency, which exists in contexts with limited institutional support and few opportunities, is a key navigational capacity, as outlined by Swartz (2021).

In spite of the earlier outlined limitation of this study, this article does expand the literature in at least three important ways. First, the findings corroborate those of Juárez and Gayet (2014), Mwaura (2017), Rogan and Reynolds (2016), and Webb (2021) on the diverse nature of post-university pathways. This study, however, provides this evidence from multiple African countries and from the African diaspora. The use of panel, rather than cross-sectional, data and qualitative data strengthens the trustworthiness of the findings. The qualitative research highlights the nature of transitions, as graduates use their navigational capacities across time and space to create non-linear, complex pathways, affirming Swartz's (2021) understanding of navigational capacities.

Secondly, the findings on self-generated income through businesses and entrepreneurship challenges some of the dominant tropes in the literature which has tended to frame 'necessity', 'opportunity' and/or the provision of training/funds as the main drivers of entrepreneurship (Bayart & Saleilles, 2019; Mgumia, 2017). Instead, we argue that these drivers overlap.

The third and most important contribution is that the findings provide evidence for universities to be active in supporting graduate transitions and also preparing current students for the realities of cultivating a livelihood after graduation. Given the tendency of graduates to generate livelihoods through business ventures, entrepreneurship education as part of a formal curriculum or through micro-credentialing should be provided. Universities can offer entrepreneurship courses or programmes that provide students with the knowledge, skills, and mindset required to start and manage their own businesses, covering topics such as business planning, marketing, financial management, and networking. However, skills training in entrepreneurship is insufficient for enabling successful small business ventures. Research indicates these activities need to be combined with creating an enabling environment, business experience and institutional support. Without adequate linkages to post-education support from public sector institutions, agencies and private sector partners, helping new business to access resources, goods and services, the chances of their success is greatly diminished. This kind of linkage should ideally begin in the planning stage of the programme.

In this way, universities could act as a connecting node for resources, partnerships and support, offering continuing education programmes or professional development courses that help graduates update their skills and knowledge to adapt to changing market trends. These programmes can enable graduates to explore new, and sometimes informal, income-generating opportunities and stay competitive in their chosen fields.

The career services offered by universities should include helping graduates explore diverse career paths and identify opportunities for income diversification. This can involve providing guidance on resume building, interview preparation, job searching, and connecting students with alumni networks and industry professionals. Universities can also provide access to resources and facilities that support income diversification.

This could include co-working spaces, business incubators or accelerators, access to industry databases or market research, and financial support through grants or seed funding programmes.

Building and maintaining a strong alumni network can be beneficial for graduates seeking income diversification. Universities can foster connections among alumni, creating platforms for collaboration, mentorship, and knowledge-sharing. This can facilitate opportunities for graduates to tap into the experiences and networks of fellow alumni who have diversified their incomes successfully. Showcasing the success stories of alumni who have successfully diversified their incomes can inspire and motivate current students and recent graduates and change the prevalent 'education to jobs' narrative.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the work of Rehan Visser and Dr Lebogang Mokwena who conducted background literature reviews on youth unemployment and livelihood generation.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance for the larger study was obtained through the Human Sciences Research Council's Research Ethics Committee, protocol number REC 6/19/06/19.

Potential conflict of interest

This article was produced in the context of The Imprint of Education study that is conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa, in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of the Foundation, its staff, or its board of directors.

Funding acknowledgement

The Imprint of Education study, on which this journal article is based, was funded by the Mastercard Foundation.

References

Alobo Loison, S. (2015). Rural livelihood diversification in sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(9), 1125-1138. DOI: 10.1080/00220388.2015.1046445. [ Links ]

Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. Culture and public action, 59, 62-63. [ Links ]

Baah-Boateng, W. (2014, November). Youth employment challenges in Africa: Policy options and agenda for future research [Conference session]. AERC biannual conference, Lusaka, Zambia.

Bayart, C., & Saleilles, S. (2019, June 3-5). Rethinking the opportunity/necessity dichotomy with a risk management-based approach [Conference session]. 11ème Congres de l'Académie de l'Entrepreneuriat et de l'Innovation, Montpellier, France.

Cerf, M. E. (2018). The sustainable development goals: Contextualizing Africa's economic and health landscape. Global Challenges, 2(8). DOI: 10.1002/gch2.201800014. [ Links ]

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013) Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120-123. [ Links ]

Cooper, A., Swartz, S., & Mahali, A. (2019). Disentangled, decentred and democratised: Youth Studies for the global South. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(1), 29-45. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2018.1471199. [ Links ]

Fairlie, R. W., & Fossen, F. M. (2017). Opportunity versus necessity entrepreneurship: Two components of business creation [Discussion paper no. 17-014]. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. http://siepr.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/17-014.pdf.

Haider, H. (2016). Barriers to youth work opportunities (K4D Helpdesk Research Report). GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

Honwana, A. (2014). 'Waithood': Youth transitions and social change. In D. Foeken, T. Dietz, L. de Haan & L. Johnson (Eds.), Development and equity: An interdisciplinary exploration by ten scholarsfrom Africa, Asia and Latin America (pp. 28-40). Brill.

International Labour Organization. (2020). Global employment trends for youth 2020: Technology and the future of jobs. International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Juárez, F., & Gayet, C. (2014). Transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 521-538. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-soc-052914-085540. [ Links ]

Kabonga, I. (2020). Reflections on the 'Zimbabwean crisis 2000-2008' and the survival strategies: The sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) analysis. Africa Review, 12(2), 192-212. DOI: 10.1080/09744053.2020.1755093. [ Links ]

Kangondo, A., Ndyetabula, D. W., Mdoe, N., & Mlay, G. I. (2023). Rural youths' choice of livelihood strategies and their effect on income poverty and food security in Rwanda. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 20. DOI: 10.1108/ajems-05-2022-0190. [ Links ]

Mayombe, C. (2017). Integrated non-formal education and training programs and centre linkages for adult employment in South Africa. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 57(1), 105-125. DOI: 10.3316/aeipt.214997. [ Links ]

Meagher, K., Mann, L., & Bolt, M. (2016). Introduction: Global economic inclusion and African workers. The Journal of Development Studies, 52(4), 471-482. DOI: 10.1080/00220388.2015.1126256. [ Links ]

Mgumia, J. (2017). Programme-induced entrepreneurship and young people's aspirations. IDS Bulletin, 48(3). https://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/index.php/idsbo/article/view/2876/ONLINE%20ARTICLE [ Links ]

Mhazo, T., & Thebe, V. (2020). 'Hustling out of unemployment': Livelihood responses of unemployed young graduates in the city of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(2), 1-15. DOI: 10.1177/0021909620937035. [ Links ]

Mwaura, G. M. (2017). The side-hustle: Diversified livelihoods of Kenyan educated young farmers. IDS Bulletin, 48(3). https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2017.126 [ Links ]

Natarajan, N., Newsham, A., Rigg, J., & Suhardiman, D. (2022). A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Development, 155, 105898. [ Links ]

Ngwenya, C. T., & Mashau, P. (2019). Entrepreneurship literacy among youth SMMEs in Ethekwini Municipality. Gender & Behaviour, 12479-12492.

Rogan, M., & Reynolds, J. (2016). Schooling inequality, higher education and the labour market: Evidence from a graduate tracer study in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 33(3), 343-360. DOI: 10.1080/0376835X.2016.1153454. [ Links ]

Schoon, I., & Lyons-Amos, M. (2016). Diverse pathways in becoming an adult: The role of structure, agency and context. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 46A, 11-20. DOI: 10.1016/j.rssm.2016.02.008. [ Links ]

Standing, G. (2018). The precariat: Today's transformative class? Development, 61(1-4), 115-121. DOI: 10.1057/s41301-018-0182-5. [ Links ]

Swartz, S. (2021). Navigational capacities for Southern youth in adverse contexts. In S. Swartz, A. Cooper, C. M. Batan & L. Kropff Causa (Eds.), Oxford handbook of global south youth studies (pp. 398-418). Oxford University Press.

Tabares, A., Londofio-Pineda, A., Cano, J. A., & Gómez-Montoya, R. (2022). Rural entrepreneurship: An analysis of current and emerging issues from the sustainable livelihood framework. Economies, 10(6), 142. DOI: 10.3390/economies10060142. [ Links ]

Thieme, T. A. (2018). The hustle economy: Informality, uncertainty, and the geographies of getting by. Progress in Human Geography, 42(4), 529-548. DOI: 10.1177/0309132517690039. [ Links ]

Webb, C. (2021). 'These aren't thejobs we want': Youth unemployment and anti-work politics in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. Social Dynamics, 47(3), 372-388. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/114865 [ Links ]

Wood, B. E. (2017). Youth studies, citizenship, and transitions: Towards a new research agenda. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(9), 1176-1190. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2017.1316363. [ Links ]

Zannella, M., Guarneri, A., & Castagnaro, C. (2019). Leaving and losing a job after childbearing in Italy: A comparison between 2005 and 2012. Review of European Studies, 11(4), 1. DOI: 10.5539/res.v11n4p1. [ Links ]

Received 29 June 2023

Accepted 24 October 2023

Published 14 December 2023

1 'Main job' was defined as where the alumnus spends most of their time, not where they earn most of their income.