Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa

versão On-line ISSN 2307-6267

versão impressa ISSN 2311-1771

JSAA vol.11 no.2 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i2.4911

RESEARCH ARTICLE

An analysis of digital stories of self-care practices among first-year students at a university of technology in South Africa

Analyse des récits numériques sur les pratiques de soins auto-administrés parmi les étudiants de première année d'une université de technologie en Afrique du Sud

Dumile GumedeI; Maureen Nokuthula SibiyaII

IFaculty Research Coordinator: Faculty of Health Sciences, Durban University of Technology, South Africa. Email: dumileg@dut.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-8628-5726

IIDeputy Vice-Chancellor: Research, Innovation and Engagement, Mangosuthu University of Technology, South Africa. Email: sibiya.nokuthula@mut.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0003-1220-1478

ABSTRACT

This article reports on a qualitative study that explored self-care practices among first-year students in managing stressors related to the first-year experience in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative data were collected using a purposive sample between March and June 2022. A total of 26 first-year students registered at a university of technology in South Africa participated in the study by producing digital stories sharing how they practised self-care. The domains of self-care were adopted as a framework and data were analysed using thematic analysis. Six domains of self-care practices emerged from the data and were categorised as physical, emotional, spiritual, relational, professional, and psychological. The findings show that first-year students engaged in a range of self-care practices across the domains of self-care including exercising, listening to music, performing ancestral rituals, donating blood, following successful people on social media, and learning new skills. Further, relational self-care was the most fundamental domain that underpinned first-year students' well-being. In contrast, oversleeping or sleep deprivation, reckless spending, and eating unhealthy food to cope with stressors related to the first-year experience pointed to unhealthy self-care practices in managing the stressors. Unhealthy self-care practices can threaten first-year students' well-being and possibly academic success. Student affairs and services need to design self-care programmes and curricula to prevent harm and support adequate self-care. In designing self-care programmes, social involvement and engagement are fundamental principles that should be emphasised. Future studies can develop a self-care inventory to identify students at risk of poor self-care and design targeted interventions to promote self-care.

Keywords: Self-care, well-being, first-year experience, first-year students, digital storytelling, South Africa, stressors, qualitative research

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article présente une étude qualitative qui a explore les pratiques de soins auto-administrés menées par les étudiants de première année pour gérer les facteurs de stress liés á l'expérience de la première année dans le contexte de la pandémie de COVID-19. Les données qualitatives ont été collectées á l>aide d'un échantillon choisi á dessein entre mars et juin 2022. Au total, 26 étudiants de première année inscrits dans une université de technologie en Afrique du Sud ont participé á l'étude en produisant des récits numériques pour partager leur pratique de soins auto-administrés. Les domaines de soins auto-administrés ont été adoptés comme cadre et les données ont été examinées á l'aide d'une analyse thématique. Six domaines de pratiques de soins auto-administrés ont émergé des données et ont été catégorisés comme suit : physique, émotionnel, spirituel, relationnel, professionnel et psychologique. Les résultats montrent que les étudiants de première année s'engagent dans une série de pratiques de soins auto-administrés en fonction des domaines de soins auto-administrés, notamment faire de l'exercice, l'écoute de la musique, la réalisation de rituels ancestraux, le don de sang, le suivi de personnes qui ont réussi sur les médias sociaux et l'apprentissage de nouvelles compétences. En outre, le domaine le plus fondamental qui sous-tend le bien-être des étudiants de première année est celui des soins auto-administrés sur le plan relationnel. Au contraire, dormir trop ou manquer de sommeil, faire des dépenses inconsidérées et manger des aliments malsains pour faire face aux facteurs de stress liés á l'expérience de la première année indiquent des pratiques de soins auto-administrés malsaines dans la gestion des facteurs de stress. Des pratiques de soins auto-administrés malsaines peuvent menacer le bien-être des étudiants de première année et éventuellement leur réussite académique. Les services d'ceuvres estudiantines doivent concevoir des programmes de soins auto-administrés et des cursus pour prévenir les dommages et soutenir des soins auto-administrés adéquats. Lors de la conception des programmes de soins auto-administrés, l'implication sociale et l'engagement sont des principes fondamentaux sur lesquels il convient de mettre l'accent. Les études futures pourront développer un inventaire des soins auto-administrés pouvant permettre d'identifier les étudiants á risquent d'une pratique déficiente afin de concevoir des interventions ciblées visant á promouvoir une meilleure pratique des soins auto-administrés.

Mots-clés: Soins auto-administrés, bien-être, experience de la première année, étudiants de première année, récit numérique, Afrique du Sud, facteurs de stress, recherche qualitative

Introduction and literature review

Higher education is widely recognised as stressful for first-year students (Mason, 2017). This is because first-year students often experience an intersection of major life transitions (Lenz, 2001), which includes transitioning from late adolescence to young adulthood and from high school to university simultaneously. More generally, late adolescents transitioning to young adulthood face several challenges and tasks. These include developing one's identity (Arnett, 2004), becoming increasingly independent (Settersten & Ray, 2010), exploring social relationships (Veksler & Meyer, 2014), assuming increasing responsibility for their health and well-being (Lenz, 2001), and embarking on a journey toward higher education (Arnett, 2007) and career aspirations. Moreover, it has also long been recognised that the move from high school to university can be stressful and demanding for first-year students (Moses et al., 2016; Tinto & Goodsell, 1994). Challenges related to transitioning from high school to university include academic performance, adapting to campus life, being more independent, financial concerns, and time management (Pretorius & Blaauw, 2020). First-year students may be experiencing independence for the first time, which is associated with being separated from their previous settings.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented stress to first-year students across the world. While all students were affected by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first-year student population remained a vulnerable population in higher education (Nyar, 2021). As a consequence of COVID-19, first-year students have had to navigate major life transitions together with the unanticipated move to online teaching and learning (Combrink & Oosthuizen, 2020), which all occurred in the new and unfamiliar university environment (Nyar, 2021). Not surprisingly, Moosa and Bekker (2022) found that first-year students in South Africa experienced anxiety due to the pandemic and its ramifications.

Therefore, navigating the intersection of major life transitions with the COVID-19 pandemic may have been challenging for first-year students. Research examining first-year experiences suggests that the challenges related to transitioning into university often prevent students from being able to care for themselves adequately (Ayala et al., 2018; Mudhovozi, 2011; Naidoo et al., 2014). For example, Bantjes et al. (2022) found higher rates of non-fatal suicidal behaviour among first-year university students in South Africa. Stressors related to the first-year experience in the context of COVID-19 compromised the various aspects of South African first-year students' well-being including the physical, emotional, social and financial (Moosa & Bekker, 2022). Getting enough sleep, healthy eating, and exercising have been reported in assisting students with experiencing less stress and negative mental health challenges (Moses et al., 2016).

While some students can navigate the transitions without any difficulty, others experience adjustment challenges and require support (Gale & Parker, 2014). Bamonti (2014) suggests that self-care operates as a mechanism for health and well-being that students can employ to survive and thrive in their higher education journeys and throughout their life courses. The concept of self-care as an essential component of health promotion became a topic of vigorous scholarly discussion during the COVID-19 pandemic to promote individual health and well-being (Martinez et al., 2021). Broadly defined, self-care refers to intentional and self-directed actions to promote holistic health and well-being (Mills et al., 2018). This definition implies a range of activities that belong to the category of self-care such as healthy eating, exercise, maintaining quality sleep, and emotion regulation strategies (Myers et al., 2012). The context of the COVID-19 pandemic was opportune for investigating the main practices in which first-year students engage for self-care as, for this cohort, the pandemic occurred at the intersection of major transitions in their lives.

Investigating self-care practice among first-year students is crucial because it is experienced in the context of the first year of study which was recently rendered even more complex by the COVID-19 pandemic. They are more likely to experience loneliness and unfulfilling social relationships in the new environment. Research has linked loneliness to negative physical and mental health outcomes (Barankevich & Loebach, 2022). Loneliness or lack of social integration can lead to a lack of interest and ability to engage in self-care practices (Narasimhan et al., 2022). As a result, students often need support in establishing the skills, knowledge, and abilities required to navigate the current environment effectively (Mason, 2017). First-year students specifically grapple not only with the self-adjustment required by the university environment with which they are mostly unfamiliar, but also with self-care demands they may need to prioritise for their academic success.

Although it is widely acknowledged that self-care involves various practices that potentially shape people's health and well-being, as far as is known, the research exploring self-care practices in the population of South African first-year students is scarce. Despite limited student self-care studies, Saadat et al. (2012) found that female students who displayed positive self-efficacy and positive mental health reported self-care activities for resisting peer influence and risky sexual behaviours and attributed their participation in religious activities and sports as shaping their self-care practices. In Hassed et al. (2009), mindfulness-based stress reduction was found as the most common strategy utilised by medical students to improve anxiety, depression, negative emotions, empathy, self-compassion, and personal control; increase health behaviours; and reduce distraction.

Additionally, student affairs services in many South African universities have designed first-year experience (FYE) programmes to support students in dealing effectively with the stressors related to the first-year experience and to promote well-being. Examples of FYE programmes are orientation seminars (Combrink & Oosthuizen, 2020; Motsabi & Van Zyl, 2017), life coaching (Mogashana et al., 2023), peer mentorship (McConney, 2023) and skills development workshops (Bengesai et al., 2022). However, few of the FYE programmes have been designed using the explicit perspectives of students themselves (Ayala et al., 2017). FYE programmes often emphasise what is wrong with students (Lewin & Mawoyo, 2014) instead of leveraging students' self-care abilities. Thus, students' voices tend to be overlooked in the design of FYE programmes which aim to promote student health and well-being. However, it is important to note that, generally, these programmes are evaluated to improve implementation and to take into consideration students' voices. There is a need to prioritise the perspectives and experiences of students by understanding their self-care ideas and practices.

Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the student-identified self-care practices of first-year students at a university of technology in South Africa. The significance of this article lies not only in exploring students' self-care practices, but also in offering detailed information on their self-care practices that can be tailored to designing FYE programmes in diverse settings. Such understanding can inform better self-care programming for students in their first year of study as they move into both higher education and young adulthood. Specific self-care interventions that are planned around the simultaneous transition can assist students in successfully bridging the gaps from late adolescence to young adulthood and from high school to university.

Theoretical framework

This study used six domains of self-care (Butler et al., 2019) as its guiding theoretical framework. These six domains of self-care are physical, emotional, spiritual, relational, professional, and psychological, which are premised on the notion that they focus on the whole person. As such, a person is viewed as a holistic being, with different life domains that require attention in each person's self-care practice (Butler et al., 2019). The proponents of the six domains of self-care (Butler et al., 2019) describe them as follows:

• Physical self-care focuses on the needs of the physical body to achieve optimal functioning.

• Professional self-care involves preventing work-related stress and stressors, mitigating the effects of burnout, and increasing work performance and satisfaction.

• Relational self-care involves creating and maintaining interpersonal connections with others.

• Emotional self-care refers to those practices that are implemented to safeguard against or address negative emotional experiences and those aimed at enhancing positive emotional experiences and well-being.

• Psychological self-care is about practices intended to satisfy intellectual needs.

• Spiritual self-care encompasses practices that give meaning to one's life and connect one to the larger world.

Adopting self-care practices can improve individual well-being during stressful events (Luis et al., 2021). Thus, the domains of self-care are important to students as they not only focus on the academic aspect of the first year of study but also how first year students cope with life transitions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As suggested by Kickbusch (1989), it is important that self-care practices are understood in terms of the meanings that students attach to their self-care practices across the six domains of self-care and the contexts in which students' self-care practices take place, and the resources available to the students to engage in self-care. The six domains of self-care were therefore appropriate to studying the self-care practices of first-year students during the pandemic.

Methods

Research design

This study was framed within an interpretive paradigm that employs the assumption that meaning in the social world is constructed by individuals engaged in the world they are interpreting (Creswell, 2007). The interpretive view resonates with this study as it facilitates the adequate capture of the students' subjective self-care practices. An exploratory qualitative research design was adopted to capture the self-care practices of first-year students. The focus was on gaining firsthand knowledge of students' self-care practices in their first year of study.

Research setting

The study was conducted at a public university of technology in the KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa. Since 2015, the university has offered an institutional general education module, which is a compulsory 12-credit module taken by all students in their first year. This module was used as the vehicle for enquiry into students' self-care practices.

Sampling and participants

A purposive sampling technique was used to select participants. The purposive sampling technique is typically used in qualitative research to identify and select individuals knowledgeable and experienced in a phenomenon of interest (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Criteria for selecting the participants were as follows: first-time entering students and currently registered for the institutional general education module in the academic year 2022. Returning students were excluded from participation in the study.

Data collection and procedures

Qualitative data were collected through the digital storytelling (DST) method. DST is an art-based research method that allows individuals to reflect on their lived experiences, using digital media to convey their narratives (Lambert, 2013). This method involves creating a short video clip, illustrated with photos, participant voices, drawings, and music (Rieger et al., 2018). DST was relevant in this study since data collection occurred remotely under COVID-19 restrictions. Data collection was conducted between March and June 2022, until data saturation was achieved as evidenced by participants providing similar responses. An invitation to participate in the study was sent through the university's notices and students' email accounts. Written instructions and one-on-one sessions through Microsoft (MS) Teams were held with individual participants on basic steps for creating a digital story. The participants were invited to record a short video, not exceeding 10 minutes, depicting the story of their self-care practices using their own devices. They were free to share their narratives in English or any local language and to select visual images or music to bring their stories to life. The use of digital storytelling allowed the participants to work on their own material at their own pace and in their own way. A topic guide contained one broad open-ended question to guide the creation of digital stories: How do you care for yourself? In addition, specific sub-questions on how they cared for themselves under each self-care domain were included. Once participants completed creating their digital stories, they were requested to submit them to the research team electronically through email, MS Teams, or WhatsApp.

Data analysis

Thematic data analysis was done using the steps for conducting qualitative data analysis devised by Babchuk (2019). The first step involved assembling materials for analysis by labelling the file of each participant's digital story with a unique number. Thereafter, the digital stories were transcribed verbatim, translated into English where necessary, and managed using NVivo 12. The second step in the analysis was re-familiarization with the dataset by reading through data transcripts in order to delve into the world of the participants as guided by Babchuk (2019). The third step focused on assigning codes to text segments and deriving categories and themes through deductive analysis. A thematic coding framework, informed by the self-care domains, was developed and used for coding the study data, with constant comparison to ensure consistency in coding. The six domains of self-care proposed by Butler et al. (2019) were used as the framework with which to categorise students' self-care practices. Lincoln and Guba's (1985) guidelines for qualitative research were adopted to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, including memo writing, immersion in the data, and debriefing sessions between the authors to verify the credibility of the analysis and interpretation.

Ethical considerations

The university's research ethics committee granted permission to conduct the study (Reference number 009/22). All participants in the study were provided with a letter of information that outlined the purpose of the study and an electronic consent form for them to sign to participate in the research study. Students were informed that their digital stories, including videos and images, would not be shared as part of protecting their confidentiality and privacy. Identifying information was treated with confidentiality and the qualitative data were anonymized prior to data analysis.

Results

Participant profile

A total of 26 participants (13 females and 13 males) voluntarily participated in the study and submitted their digital stories about their self-care practices. The ages of the participants ranged from 17 and 27 years, with the majority of students aged between 18 and 20 years.

Self-care practices adopted by first-year students

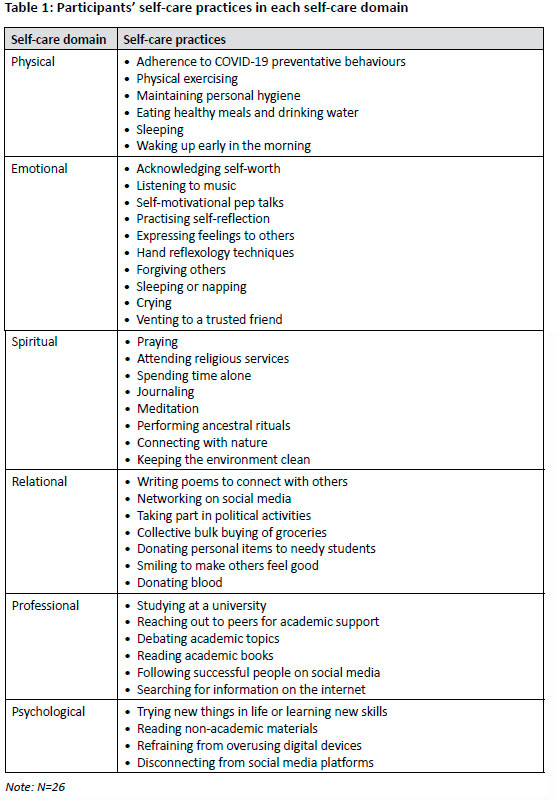

Table 1 summarises the self-care activities adopted by students under each domain of self-care.

Physical self-care

Data collection was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, therefore, participants recounted how they were adhering to the recommended COVID-19 preventative behaviours to promote physical self-care. The measures that participants applied for physical self-care included vaccinating against COVID-19, wearing face masks, washing hands regularly, using hand sanitizers, and keeping physical distance from others.

To help myself not to get infected by this virus, I follow all rules and protocols given by the government. If I'm with my friends or in the gym or anywhere where there are two or more people, I keep my 1,5m distance from them while wearing my face mask. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, I normally encourage my friends to take care of themselves because this is a critical time to be safe. Who knows, maybe this pandemic would not be kind to us. So, I rather keep it away from me and stay safe all the time and keep others near me safe too. (P25, Male, 18yrs)

It was clear that adhering to COVID-19 regulations was not only for personal physical self-care but out of a sense of responsibility for ensuring that surrounding others were protected from infection. Although the COVID-19 regulations seemed to promote hygiene among students, complying with the university regulations prior to entering university premises was regarded as burdensome:

Uploading my COVID-19 vaccination certificate was one of my biggest problems because I didn't know how to upload it. It took me three days to accomplish this requirement. (P6, Male, 19yrs)

Apart from adhering to COVID-19 preventative measures, the participants mentioned that achieving physical fitness was important for their physical self-care. Physical exercising including playing sports, jogging, walking, and going to the gym were the activities that the participants adopted for taking care of their bodies:

I like playing soccer, lifting, and boxing. In fact, I grew up playing soccer in school. As such, during the week, I regularly go to practice at the soccer field for my immune system to remain strong. I am not so much into lifting gym equipment but, occasionally, I do lift when I get a chance. Also, I rarely play boxing sport; however, I enjoy watching it on TV. So, at times, I would go to the gym to learn fighting, punching, and other things related to boxing. (P7, Male, 17yrs)

The desire for strong immunity combined with an ideal body shape motivated students to engage in physical self-care. Further, maintaining personal hygiene including bathing and keeping their living space clean were also activities adopted by students for physical self-care.

It was also noted that the COVID-19 pandemic shaped self-care activities hence healthy eating and water drinking were also specified as salient means of physical self-care:

In line with the COVID-19 pandemic, I eat healthy meals and, regularly, drink more water for my physical self-care. (P11, Female, 20yrs)

While some participants prioritised healthy meal plans, others, particularly male students, stated challenges associated with eating healthy food:

I wasn't the one to prepare food at home. Essentially, I don't know how to cook. I usually eat cornflakes, bread, and also noodles for my breakfast. (P10, Male, 19yrs)

In this regard, changing home environment and individual skills required for food preparation shaped the choice of unhealthy food that some participants opted to eat and their physical self-care abilities. Another significant aspect of physical self-care that the participants narrated was sleeping, resting, and waking up early in the morning in order to maintain overall well-being:

I give myself enough time to sleep as much as my body needs to. I also try not to spend more time resting than studying. It is important to set the time for how many hours I spend sleeping and how many hours I spend studying. I cannot spend most of my time sleeping than studying. I generally do give myself much time to rest. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

As reflected in the above excerpt, quality of sleep was characterised by the number of sleep hours. However, sleep deprivation due to academic workload compromised quality of sleep:

I'm not good at sleeping. Mostly, I sleep five hours or less because, as new students at the university, we are extremely busy studying. For this reason, I normally study until late hours. (P10, Male, 19yrs)

The volume of academic workload did not only compromise the participants' quality of sleep, but it was also mentally distressing:

I get less time or no time at all to take care of myself mentally and physically for the reason that I'm always stressed and worried about what [academic task] am I going to do next. Obviously, I'm always stressed about submitting all my assignments on time. As a result, I don't often go out anymore...During the day, I'm always in front of my [computer] keyboard working on my assignments. (P13, Male, 21yrs)

Although participants recognised the need for and importance of engaging in physical self-care, the academic workload hindered effective self-care for first-year students.

Emotional self-care

Participants described a range of activities through which they practiced emotional self-care. First, acknowledging self-worth was featured in the participants' digital stories when they described the value that they placed on themselves and their emotional well-being. They stated the importance of prioritising their feelings and emotions to be able to relate with peers. Second, participants also strongly believed that listening to music played an integral role in their emotional self-care to counter negative and difficult experiences in their first year of study:

I usually listen to music whenever I'm angry or whenever something breaks my heart. Listening to music helps me the most. Music calms me down whenever I'm not okay. (P2, Female, 17yrs)

Music played a role in improving feeling good and functioning well under the difficult circumstances of being a first-year student:

When I listen to music - it's so nice that it just blocks out the world as if nothing is going on except me at that moment. So, things like that usually help me to recoup and prepare myself for the week or the day before me so that I can come back relaxed with a stressfree mind. (P8, Female, 19yrs)

Third, self-motivational pep talks were employed as a strategy to address negative emotional experiences that were associated with being a first-year student:

I do however remain calm and give myself some motivational pep talks to start my day off - just to know I can handle the university life and convince myself that everything will be all right. (P8, Female, 19yrs)

Lastly, various other emotional self-care activities participants reported included (a) practising self-reflection as a way of monitoring how they felt about their journey of first-year study or negative experience; (b) expressing feelings to others to ensure that others around them were aware of their emotions; (c) hand reflexology techniques to release tension; (d) forgiving others who may have hurt them instead of holding a grudge; (e) sleeping or napping to overcome fatigue or cope with emotional distress; (f) crying as a way of releasing negative emotions; and (g) venting to a trusted friend in order to share traumatic or distressing experiences.

Spiritual self-care

The participants listed several spiritual self-care practices to ignite their inner spirit. These included praying and attending religious services. Although these practices were for students' spiritual self-care, it was clear that they were also enabling a successful transition to young adulthood and independent living:

I'm a dedicated Christian. As a result, I enjoy and like being in church for my spiritual revival. When I'm in church, I learn a lot from other congregants. They advise me on how to behave as a young woman at university who is no longer staying at home with her parents. Their teachings are helpful for me to stay safe and grow spiritually while studying at the university. (P12, Female, 18yrs)

Additionally, some participants talked about spending time alone, journaling, and meditation as the activities that they adopted for spiritual self-care. Others, particularly male students, mentioned connecting with ancestors through performing ancestral rituals for personal and cultural reasons as a form of spiritual self-care:

My family believes a lot in ancestors hence I also believe in ancestors. At home, we regularly perform ancestral rituals to communicate with our ancestors. So, anytime I need spiritual help, I would simply reach out to my ancestors and things get resolved. My ancestors are our deceased family members who look after me as an alive human being on earth. They definitely play a huge role in my life and the person I am. (P7, Male, 17yrs)

As reflected in the above excerpt, spiritual self-care practices were interwoven with the aspect of students' personal identities in terms of how they viewed themselves and their values. Moreover, students' spiritual self-care practices also encompassed much more than religious and cultural activities. Connecting with nature was regarded as a form of spiritual self-care. They mentioned activities such as taking a walk in the surroundings of a natural environment, planting vegetables and flowers, and looking after cows:

At home, we have domestic cows and agricultural plantations. Whenever I go home on weekends, I ensure that I engage in farming at our agricultural plantations and take time to look after our domestic cows. Domestic cows are very important to me because they are also our source of family income. Sometimes, my family would sell cows to get money for food and other basic needs. (P7, Male, 17yrs)

Looking after the cows was not only for spiritual self-care but it also facilitated means of livelihood for securing financial resources. Furthermore, keeping the environment clean was another way of engaging in spiritual self-care:

I respect nature as much as I respect myself. I do that by avoiding polluting water as it can kill the water ecosystem. It is my belief that plants and animals need to be taken care of as much as humans. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

The participants viewed themselves as co-existing and connected to the natural environment and this perception shaped their spiritual self-care practices.

Relational self-care

With respect to relational self-care, writing poems and networking on social media were stated as practices that some participants adopted for reaching out to and impacting the lives of others:

I am also poetic and use poems to connect with other students. Other students are very happy to learn from my thoughts and ideas, which I express in poetry. Naturally, I am an outspoken person. As such, I get satisfaction from positively influencing other students. (P9, Male, 19yrs)

Poetry and social media were tools that the participants used to create connections with others and to ideologically influence their social networks. One participant explained that poetry was a form of entertainment to help others to overcome isolation and loneliness at the university. Additionally, taking part in political activities was regarded as a way of changing society and the lives of others:

As a young person, I participate in voting for student leaders within the university and political leaders in government. Also, I educate myself about the political landscape in my country through interacting with other students. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

The participants also mentioned that they tapped into the power of collective bulk buying of groceries by clubbing together with friends on campus as a means of relational self-care. While collective buying of groceries involved budgeting and saving to afford to buy in bulk, the lack of skills in handling money was a concern expressed by male students.

Recently, we received large payments of funding aid allowance. As I speak, right now, I don't have even a cent! (P9, Male, 19yrs)

Unnecessary spending on non-essential items left students with no money and distressed:

As soon as you get the money you get confused about what you wanted and what you see and you end up buying unnecessary things which will then give you stress. (P25, Male, 18yrs)

Competition and owning luxury items were pointed out as driving unnecessary spending among students:

I make sure that I save money, at least a certain amount per month so that it can help me when I need help in the future or during emergencies. I am finding it important that I don't compete with other university students but be myself because we come from different backgrounds. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

The inability to handle personal finances was indeed emotionally distressing for the participants and it compromised their well-being. Participants expressed an interest in financial literacy education for first-year students:

Of all the problems that I have in the world is that I'm unable to handle money. Even at home, they usually warn me that I would not be able to buy a house with the way I spend money. I would be happy to participate in a financial literacy programme so that I learn to save money since I can see that I have a problem with saving money. (P7, Male, 17yrs)

Furthermore, it was noted that donating personal items to needy students was an effort that the participants made to maintain and enhance interpersonal connections with others:

If other people don't have what they need, I rather give them my own things. I just cannot take it to see another person in need, that's why I simply give them my things. The reason I give them my things is that I want them not to feel alone in the problem. (P9, Male, 19yrs)

Apart from donating supplies to needy students, one participant mentioned donating blood as an important contribution to society:

For me, I donate blood since I'm now over 18 years old and legally qualified to be a blood donor. It gives me joy to donate blood for the sake of saving the lives of other people. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

Donating blood was not only a form of relational self-care to save lives but considered an affirmation of young adulthood.

Lastly, smiling to make others feel good was how both male and female students maintained social networks with others for relational self-care, as illustrated:

Smiling is one of the ways I connect with people. I always smile and confront others with a smile so that it would be easier for them to talk to me, feel comfortable around me, and open up to me. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

Smiling to make others feel good was not only important for students to foster relationships in a new university environment but also for dealing with isolation and loneliness during the first year of university.

Professional self-care

First, the digital stories revealed that the participants typically viewed studying at a university as a means of professional self-care considering that they would be acquiring academic knowledge and skills to facilitate success in society. Gaining admission to university while many other young people did not get the opportunity to study boosted their self-esteem and self-perceptions that they would become a generation of successful young people:

The fact that I am studying at the university is my contribution to the world so that it becomes a better place to live in. (P7, Male, 17yrs)

Second, reading academic books and studying in the library were stated as part of professional self-care in relation to academic success:

I like reading a lot; not novels. I read challenging materials. By that I mean, something that would make me curious for more information. It is for this reason that after completing Grade 12 I chose to come to the university to get challenged academically. (P7, Male, 17yrs)

Third, reaching out to peers for academic support and searching for information on the internet were additional strategies that participants employed to mitigate academic-related stressors and promote their professional self-care:

I like searching for information on Google. I also reach out to my classmates to explain concepts and topics that I did not understand in class, then they would explain them to me. (P12, Female, 18yrs)

Another participant stated:

I help other students who are struggling with digital connections. It could be Moodle or MS TEAMS so that they can join online classes. By so doing, it advances my academic and digital skills. (P10, Male, 19yrs)

Last but not least, debating academic topics and concepts with a view of developing critical thinking and reflection skills was stated as necessary for university and professional self-care:

Often, I debate with others a lot on academic topics since I believe it improves my thinking skills and those that I interact with. (P4, Female, 22yrs)

Finally, following successful people on social media inspired the participants to thrive for success within the university environment:

I follow successful people on social media who are in the same field of study as mine in order to learn how they did it in life or how they got where they are. It really motivates me and helps me to gain knowledge and skills in order to know how to do those sorts of things. It also helps me to be able to do the same and gain skills so that others can learn from me. (P25, Male, 18yrs)

This also reflects that social media presence supported the students in acquiring information while establishing wide networks.

Psychological self-care

To satisfy their personal intellectual needs and expand their knowledge and skills, the participants mentioned trying new things in life or learning new skills, listening to podcasts, and reading novels and newspapers:

I'm not scared to try new things which I never knew before. For example, I didn't how to do a digital story; however, I told myself 'let me just do it' to pick up a new skill. (P9, Male, 19yrs)

While social media and technological devices were popular among the participants, some mentioned that they occasionally refrained from using digital devices and disconnected from social media platforms to promote optimal psychological self-care.

Discussion

This study shows that first-year students engage in a range of self-care practices across the six domains of self-care. In their first year of study, students incorporate self-care values to enhance health and well-being. However, self-care does not appear as an individual act, rather it is a collective product that emerges from the interactions between the individual first-year students and others.

The study findings reveal that student access to higher education is regarded as a means of self-care and a tool to access future employment. These findings are not surprising considering that many students are first-generation and come from poor households in South Africa (Naidoo & Cartwright, 2020). Pather et al. (2017) explain that access to higher education has resulted in an increased representation of students from low-income households, who are often first-generation students. Moreover, the findings from this study highlight that universities are critical spaces in which first-year students apply self-care practices in order to shape themselves into responsible citizens. Donating blood and participating in political activities indicate that students are conscious of the roles that they can play in society for social justice and community-building. It could be perceived as affirmation that they have reached young adulthood. Furthermore, the findings of this study show that students care for their peers. This was evidenced by their donation of personal items to needy students as a form of self-care. Helping others served the purpose of relational self-care.

It was evident from this study that connecting with others promoted students' sense of belonging and connectedness to the university, thus enhancing their self-care. The findings of this study revealed that connecting with others in the university was important for first-year students to develop relationship skills. We found that relational self-care was the most fundamental domain that underpinned first-year students' well-being. As explained by Veksler and Meyer (2014), young adulthood facilitates opportunities for navigating interpersonal relationships with peers. Subsequently, the pandemic limited physical human interaction, thus students fostered self-care activities that supported social connectedness in each domain of self-care. For example, while students sought to enhance their professional self-care by reaching out to their peers for academic support, this also addressed their relational self-care needs. These findings align with Mntuyedwa's (2023) study, which holds that social integration is crucial to first-year student well-being.

As in the studies of Labbe et al. (2007) and Vidas et al. (2021), participant students listened to music to reduce the negative emotional effects of stress, anger, anxiety, and to cope with stress. For example, a study among first-year students in Australia reported that music listening was rated as the most effective strategy for managing COVID-19 stress (Vidas et al., 2021) This can be explained by the fact that music plays an important role in youth culture to claim cultural space in public and at home, to explore and establish identities, and for positive mental health (Papinczak et al., 2015). In Papinczak et al. (2015) young people listen to music to modify undesirable emotions as a coping strategy through which well-being is restored. The excess of music genres available to music listeners on the internet has popularised incorporating music into students' self-care practices. However, the intensity or volume of the music played can also have a negative effect on the well-being of the music listeners and those around them. A study conducted by Dolegui (2013) indicated that loud music is a stronger distractor and obstructs cognitive performance. Our study did not generate data on the intensity and the type of music that students listened to, and this aspect may need further investigation.

While collective purchasing of groceries enhanced students' relational self-care, a lack of experience in handling money comprised students' emotional well-being, and it could also compromise their academic success. These findings corroborate those of Mngomezulu et al. (2017), that inexperience in money handling, excitement at accessing money for the first time, difficulties of not knowing what to do with the money, and a lack of budgeting skills contribute to students' misuse of funds which in turn can result in poor academic performance. Poor financial literacy in first-year students may lead to a cycle of debt before they complete their studies and are absorbed into employment. While financial support facilitates access to higher education for students from low-income families, the lack of financial skills could compromise their academic success and self-care when they are distressed by mishandling the allowances given to them and the need to compete with others.

Further, it should not be assumed that students assume the responsibility of self-care with the insight or skills required to implement healthy self-care practices or that they use available resources for self-care. Previous studies have reported that university students adopt ineffective self-care and coping strategies, and struggle to access support services that could help them in managing challenges (Mudhovozi, 2011; Naidoo et al., 2014). Consistent with the literature, our study found that none of the students mentioned using available student counselling support services within the university to enhance their self-care. It is possible that first-year students are not aware of the counselling support services or they rely on other healing systems, for example, spiritual healing systems that are either religious or indigenous. According to Musakwa et al. (2021), the lack of sufficient information/poor health literacy was one of the barriers to accessing health services among first-year students in South Africa. Another South African study also found very low mental healthcare treatment utilisation among first-year university students (Bantjes et al., 2020). Naidoo and Cartwright (2020) recommend that student counselling services be transformed in a manner that promotes holistic student well-being. For example, counselling services could integrate multiple forms of healing systems that students can use to promote health and well-being.

Our findings further indicate that some students did not engage in healthy self-care practices. This was evident in that they mentioned practising harmful self-care practices (e.g. oversleeping and eating unhealthy foods). These findings are worrying given that such harmful practices could also risk academic performance for first-year students. The finding nevertheless needs to be taken seriously because the relationship between psychological stress and academic performance (Naidoo et al., 2014) indicates a potential risk for first-year students dropping out of their studies due to adopting unhealthy self-care practices. Students should, therefore, be assisted in developing effective self-care practices to deal with stress in constructive ways.

While self-care courses are being implemented, evaluated, and adapted as part of existing curricula in various developed countries, South African universities currently lag behind compared with efforts elsewhere in the self-care curriculum for students. There is a need to infuse self-care into the first-year curriculum. The self-care course could introduce students to many other tools of self-care that they could use in order to enhance their well-being. Effective self-care in first-year of study requires both the engagement of students as well as the support of the higher education system.

Conclusion

This study investigated and gained insight into self-care practices adopted by first-year students at a university of technology in South Africa in the context of COVID-19. It is evident that first-year students' self-care practices and relational self-care are intertwined in each domain of self-care. Thus, social involvement and engagement are fundamental principles that should be emphasised in designing self-care interventions for first-year students. While self-care is important for enhancing well-being, unhealthy self-care practices can threaten students' well-being and possibly academic success. Student affairs and services need to design harm prevention interventions and curricula to support adequate self-care and sustainable healthy behaviours. Future studies can develop a self-care inventory to identify students at risk of poor self-care and design targeted interventions to promote self-care.

Strengths and limitations

This study offers a noteworthy contribution to the field of health promotion. It has addressed a primarily overlooked area of student self-care in the Southern African literature and adopted a student-centred approach to supporting the voice of students in informing intervention development within the higher education context. Additionally, this study is important for the African context because it takes the aspects of self-care beyond most western literature and makes local practices of self-care significant. Several limitations of this study, including poor internet connectivity, quality of digital stories, and participants' limited technological skills, are already discussed in our published work (Gumede & Sibiya, 2023). Earlier, we also highlighted the strategies that we adopted to address the limitations including that the participants were afforded flexible timelines to create the digital stories and were provided with one-on-one guidance on how to create them.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants for their participation. We are also immensely grateful to Dr P.R. Gumede for technical support during data collection and Dr A. Oluwatobi for commentary that greatly improved the manuscript.

Ethics statement

Permission to conduct this study was granted by the case university's research ethics committee (Reference number 009/22). All ethics protocols were followed by the researchers.

Potential conflict of interest

None.

Funding acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) (Grant No: 138175). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and or in manuscript authorship.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x [ Links ]

Ayala, E. E., Omorodion, A. M., Nmecha, D., Winseman, J. S., & Mason, H. R. C. (2017). What do medical students do for self-care? A student-centered approach to well-being. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 29(3), 237-246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2016.1271334 [ Links ]

Ayala, E. E., Winseman, J. S., Johnsen, R. D., & Mason, H. R. C. (2018). U.S. medical students who engage in self-care report less stress and higher quality of life. BMC Medical Education, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1296-x [ Links ]

Babchuk, W. A. (2019). Fundamentals of qualitative analysis in family medicine. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7, e000040. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000040 [ Links ]

Bamonti, P. M., Keelan, C. M., Larson, N., Mentrikoski, J. M., Randall, C. L., Sly, S. K., Travers, R. M., & McNeil, D. W. (2014). Promoting ethical behavior by cultivating a culture of self-care during graduate training: A call to action. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 8(4), 253-260. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000056 [ Links ]

Bantjes, J., Breet, E., Saal, W., Lochner, C., Roos, J., Taljaard, L., Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Bruffaerts, R., Kessler, R. C., & Stein, D. J. (2022). Epidemiology of non-fatal suicidal behavior among first-year university students in South Africa. Death Studies, 46(4), 816-823. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1701143 [ Links ]

Bantjes, J., Saal, W., Lochner, C., Roos, J., Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Kessler, R. C., & Stein, D. J. (2020). Inequality and mental healthcare utilisation among first-year university students in South Africa. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-0339-y [ Links ]

Barankevich, R., & Loebach, J. (2022). Self-care and mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Social and physical environment features of interactions which impact meaningfulness and mitigate Loneliness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879408 [ Links ]

Bengesai, A. V., Paideya, V., Naidoo, P., & Mkhonza, S. (2022). Student perceptions on their transition experiences at a South African university offering a first-year experience programme. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v10i2.4084 [ Links ]

Butler, L. D., Mercer, K. A., McClain-Meeder, K., Horne, D. M., & Dudley, M. (2019). Six domains of self-care: Attending to the whole person. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1482483 [ Links ]

Combrink, H. M. E., & Oosthuizen, L. L. (2020). First-year student transition at the University of the Free State during COVID19: Challenges and insights. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 8(2), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v8i2.4446 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage.

Dolegui, A. S. (2013). The impact of listening to music on cognitive performance. Inquiries Journal, 5(9), 517-524. [ Links ]

Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2014). Navigating change: A typology of student transition in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 39(5), 734-753. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.721351 [ Links ]

Gumede, D., & Sibiya, M. N. (2023). Ethical and methodological reflections: Digital storytelling of self-care with students during the COVID-19 pandemic at a South African university. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(6), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001682 [ Links ]

Hassed, C., de Lisle, S., Sullivan, G., & Pier, C. (2009). Enhancing the health of medical students: Outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(3), 387-398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9125-3 [ Links ]

Kickbusch, I. (1989). Self-care in health promotion. Social Science & Medicine, 29(2), 125-130. DOI: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90160-3 [ Links ]

Labbé, E., Schmidt, N., Babin, J., & Pharr, M. (2007). Coping with stress: The effectiveness of different types of music. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback, 32(3-4), 163-168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-007-9043-9 [ Links ]

Lambert, J. (2013). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community (4th ed.). Routledge.

Lenz, B. (2001). The transition from adolescence to young adulthood: A theoretical perspective. The Journal of School Nursing, 17(6), 300-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/10598405010170060401 [ Links ]

Lewin, T., & Mawoyo, M. (2014). Student access and success: Issues and interventions in South African universities. Inyathelo: The South African Institute for Advancement.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

Luis, E., Bermejo-Martins, E., Martinez, M., Sarrionandia, A., Cortes, C., Oliveros, E. Y., Garces, M. S., Oron, J. V., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2021). Relationship between self-care activities, stress and well-being during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-cultural mediation model. BMJ Open, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048469 [ Links ]

Martinez, M., Luis, E. O., Oliveros, E. Y., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Sarrionandia, A., Vidaurreta, M., & Bermejo-Martins, E. (2021). Validity and reliability of the self-care activities screening scale (SASS-14) during COVID-19 lockdown. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01607-6 [ Links ]

Mason, H. D. (2017). Stress-management strategies among first-year students at a South African university: A qualitative study. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 5(2), 131-149. https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v5i2.2744 [ Links ]

McConney, A. (2023). Peer helpers at the forefront of mental health promotion at Nelson Mandela University: Insights gained during Covid-19. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i1.4220 [ Links ]

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Mills, J., Wand, T., & Fraser, J. A. (2018). Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care, 17(63), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0318-0 [ Links ]

Mngomezulu, S., Dhunpath, R., & Munro, N. (2017). Does financial assistance undermine academic success? Experiences of 'at risk' students in a South African university. Journal of Education, 68, 131-148. [ Links ]

Mntuyedwa, V. (2023). Exploring the benefits for first-year university students joining peer groups: A case study of a South African university. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i2.4911 [ Links ]

Mogashana, D., Basitere, M., & Ndeto Ivala, E. (2023). Harnessing student agency for easier transition and success: The role of life coaching. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i1.4206 [ Links ]

Moosa, M., & Bekker, T. (2022). Working online during COVID-19: Accounts of first year students experiences and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.794279 [ Links ]

Moses, J., Bradley, G. L., & O'Callaghan, F. v. (2016). When college students look after themselves: Self-care practices and well-being. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 53(3), 346-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2016.1157488 [ Links ]

Motsabi, S., & Van Zyl, A. (2017). The University of Johannesburg (UJ) first year experience (FYE) Initiative. In The first year experience in higher education in South Africa: A good practices guide (pp. 18-29). South African National Resource Centre.

Mudhovozi, P. (2011). Analysis of perceived stress, coping resources and life satisfaction among students at a newly established institution of higher learning. South African Journal of Higher Eduation, 25(3), 510-522. [ Links ]

Musakwa, N. O., Bor, J., Nattey, C., Lönnermark, E., Nyasulu, P., Long, L., & Evans, D. (2021). Perceived barriers to the uptake of health services among first-year university students in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 16(1 January). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245427 [ Links ]

Myers, S. B., Sweeney, A. C., Popick, V., Wesley, K., Bordfeld, A., & Fingerhut, R. (2012). Self-care practices and perceived stress levels among psychology graduate students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(1), 55-66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026534 [ Links ]

Naidoo, P., & Cartwright, D. (2020). Where to from here? Contemplating the impact of COVID-19 on South African students and student counseling services in higher education. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 00(00), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2020.1842279 [ Links ]

Naidoo, S., van Wyk, J., Higgins-Opitz, S., & Moodley, K. (2014). An evaluation of stress in medical students at a South African university. South African Family Practice, 56(5), 258-262. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2014.980157 [ Links ]

Narasimhan, M., Aujla, M., & Van Lerberghe, W. (2022). Self-care interventions and practices as essential approaches to strengthening health-care delivery. The Lancet Global Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00451-X

Nyar, A. (2021). The 'double transition' for first-year students: Understanding the impact of Covid-19 on South Africa's first-year university students. Journal for Students Affairs in Africa, 9(1), 77-92. https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v9i1.1429 [ Links ]

Papinczak, Z. E., Dingle, G. A., Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., & Zelenko, O. (2015). Young people's uses of music for well-being. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(9), 1119-1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1020935 [ Links ]

Pather, S., Norodien-Fataar, N., Cupido, X., & Mkonto, N. (2017). First year students' experience of access and engagement at a university of technology. Journal of Education, 69, 161-184. [ Links ]

Pretorius, M., & Blaauw, D. (2020). Financial challenges and the subjective wellbeing of firstyear students at a comprehensive South African university. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 8(1), 47-64. https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v8i1.4181 [ Links ]

Rieger, K. L., West, C. H., Kenny, A., Chooniedass, R., Demczuk, L., Mitchell, K. M., Chateau, J., & Scott, S. D. (2018). Digital storytelling as a method in health research: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 7(41), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0704-y [ Links ]

Saadat, M., Ghasemzadeh, A., & Soleimani, M. (2012). Self-esteem in Iranian university students and its relationship with academic achievement. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 10-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.007 [ Links ]

Settersten, R. A., & Ray, B. (2010). What's going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children, 20(1), 19-41. https://about.jstor.org/terms [ Links ]

Tinto, V., & Goodsell, A. (1994). Freshman interest groups and the first year experience: Constructing student communities in a large university. Journal of the First-Year Experience & Students in Transition, 6(1), 7-28. [ Links ]

Veksler, A. E., & Meyer, M. D. E. (2014). Identity management in interpersonal relationships: Contextualizing communication as central to research on emerging adulthood. In Emerging Adulthood, 2(4), 243-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814558061 [ Links ]

Vidas, D., Larwood, J. L., Nelson, N. L., & Dingle, G. A. (2021). Music listening as a strategy for managing COVID-19 stress in first-year university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647065 [ Links ]

Received 29 June 2023

Accepted 21 November 2023

Published 14 December 2023