Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa

versão On-line ISSN 2307-6267

versão impressa ISSN 2311-1771

JSAA vol.11 no.2 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i2.4898

RESEARCH ARTICLE

"Giving back is typical African culture": Narratives of give-back from young African graduates

"Ukubuyisela kuyisiko lase Afrika elijwayelekile": Izindaba zokubuyisana kwabafundi abasebasha base-Afrika

Alude MahaliI; Tarryn de KockII; Vuyiswa MathamboIII; Phomolo MaobaIV; Anthony MugeereV

IChief Research Specialist: Equitable Education and Economies programme, Human Sciences Research Council; Honorary Lecturer: School of Arts at the University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa. Email: amahali@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-9686-8239

IIHuman Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: tarryngabidekock@gmail.com. ORCid: 0000-0001-8570-5138

IIIProject Manager: Equitable Education and Economies division, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa. Email: vmathambo@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-0638-0708

IVSenior Researcher: Equitable Education and Economies (EEE) division, Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa. Email: pmaoba@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-0205-5537

VSenior Lecturer: Department of Sociology & Anthropology, School of Social Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email: anthony.mugeere@mak.ac.ug. ORCid: 0000-0002-7349-9901

ABSTRACT

This article presents a collection of narrative examples on how a cohort of African graduates, who are beneficiaries of a scholarship from a global foundation, understand and practice giving back. The scholarship programme aims to cultivate and support a network of like-minded young leaders who are committed to giving back by providing training and mentorship that reinforces the core values of transformative leadership and a commitment to improving the lives of others. To investigate these ideas, the Human Sciences Research Council is tracking recent graduates of the scholarship programme using a longitudinal cohort study design consisting of a tracer study, annual qualitative interviews with scholarship alumni, and smaller collaborative enquiries. Beginning in 2019 and tracking alumni for a five-year period, the study involves alumni from seven study sites. Findings from the study show that alumni exhibit a strong sense of social consciousness including an alignment of their understanding and practices of give-back with deeply embedded African notions of give-back as a 'ripple effect', reciprocity and ubuntu. Alumni acknowledged that there was not only one way to give, indicating that they participated in give-back in relation to their capacity, usually beginning with contributions to the family. As they became more established in their careers, their sphere of give-back increased with their reach expanding to the broader community. A low proportion of alumni felt that they were making an impact on an institutional or systemic level. Findings also show the impactful position that university partners hold in fostering give-back engagement among students and their potential role in supporting alumni after graduation. The article argues that nurturing social consciousness in young people and an understanding of give-back as collective movement building can contribute to solving development and social justice problems in Africa.

Keywords: Give-back, African graduates, transformative leadership, social consciousness, ubuntu, scholarships, social responsibility, higher education

IQOQA

Lo mbhalo wethula iqoqo lezibonelo ezilandisayo zokuthi iqeqebana labafundi base-Afrika abaneziqu abahlomule ngomfundaze ovelele, ovela kuSisekelo Somhlaba, baqonde futhi bazijwayeze kanjani ukubuyisela. Uhlelo lomfundaze luhlose ukuhlakulela nokweseka inethiwekhi yabaholi abasebasha abanomqondo ofanayo abazibophezele ekubuyiseleni ngokunikeza ukuqeqeshwa nokwelulekwa okuqinisa izilinganiso ezibalulekile zobuholi obuguqukayo nokuzibophezela ekwenzeni ngcono izimpilo zabanye abantu, ukuze iphenywe le mibono. Umkhandlu Wokucwaninga Ngesayensi Yabantu ulandelela abasanda kuthola iziqu ohlelweni lomfundazwe usebenzisa ubuchwepheshe bocwaningo lweqembu lesikhathi eside luhlanganisa ucwaningo lokuthola izingxoxo ezinohlonze zaminyaka yonke nababefunde ngazo kanye nemibuzo emincane yokusebenzisana. Kusukela ngo-2019 kanye nokulandela umkhondo we-alumni isikhathi seminyaka emihlanu, lolu cwaningo lubandakanya abafundi bakudala abavela ezindaweni eziyisikhombisa zocwaningo. Okutholakele kubonisa iqoqo elibonisa umuzwa oqinile wokuqaphela umphakathi okuhlanganisa ukuqondanisa phakathi kwendlela ababekuqonda ngayo nokwenza ukubuyisela ngemibono ejulile yase Ningizumu-Afrika yokubuyisela 'njengomphumela ozwakalayo', ukubuyisana kanye nobuntu. Ebakade bengabafundi bavumile ukuthi ayikho indlela eyodwa yokunikela, okukhombisa ukuthi babambe iqhaza ekubuyiseleni ngokwesikhundla sabo, ngokujwayelekile baqala ngokunikela emndenini. Kodwa-ke, njengoba beqala ukuqina emisebenzini yabo, izinga labo lokubuyisela liyenyuka futhi ukufinyelela kwabo kakhulu emphakathini obanzi. Ingxenye ephansi yabakade bengabafundi bezwa sengathi benza umthelela ezingeni lesikhungo noma lesistimu. Okutholakele futhi kukhombisa isikhundla esinomthelela ababambisene nabo basenyuvesi ekukhuthazeni ukusebenzelana kokubuyisela phakathi kwabafundi kanye nendima yabo engaba khona ekusekeleni ama-alumni ngemva kokuphothula iziqu. Leli phepha ligomela ukuthi ukukhulisa ukuqonda komphakathi kanye nokuqonda okukhulayo kokubuyisela njengokwakha ukunyakaza okuhlangene kuyadingeka ukuze kuxazululwe izinkinga zentuthuko kanye nobulungiswa bezenhlalakahle e-Afrika.

Amagama Angukhiye: Ukubuyisela, abaphothulile e-Afrika, imfundo ephakeme, isibopho emphakathini, ubuholi obuguqukayo, ukuqaphela komphakathi, ubuntu

Introduction

This article presents a collection of narrative examples on how a cohort of African graduates, who are beneficiaries of a prominent scholarship from a global foundation, understand and practice giving back. Beneficiaries are recruited on the basis of financial need, academic talent and by exhibiting leadership traits and a commitment to giving back. These are usually individuals already engaged in community leadership activities (Bono et al., 2010). The scholarship programme aims to cultivate and support a network of like-minded young leaders by providing training and mentorship that reinforces the core values of transformative leadership and a commitment to improving the lives of others. The Human Sciences Research Council is undergoing a longitudinal cohort study comprising an Alumni Tracer Study (ATS) and a qualitative study, which includes annual interviews with scholarship alumni, to investigate these ideas. The study involves alumni from Kenya, Ethiopia, South Africa, Rwanda, Uganda, Ghana and the African diaspora (those who studied off-continent and now reside outside of the African continent).1In addition, key informant interviews (KIIs) have been conducted with implementing partners of the scholarship programme (these are 25 university and NGO partners in North America, Central America, Europe and Africa).

The ATS is a longitudinal panel study designed to survey the scholarship programme alumni who received their scholarships through 25 implementing institutions. Given the relatively small population of tertiary alumni,2 all of them were included in the study with a view to draw out a representative sample which could then be weighted to the expected population (839 out of a possible 1,161). The population of secondary alumni3was 8,650, of whom a sample of 1,000 was expected. A randomised stratification sampling process was undertaken with oversampling to allow for attrition in subsequent waves of the study. In the qualitative sample, a total of 122 participants from the countries listed above were recruited and interviewed annually.

Using these mixed-method research activities, recent graduates of the scholarship programme are being tracked longitudinally for five years, beginning in 2019. It is a study concerned with understanding success in ethical and transformative leadership, and how this is affected by context and education. The overall objective is to provide evidence at multiple levels on beneficiary pathways and the contributions they are making to their families, schools/institutions, communities, organisations, and societies, including the ways in which their give-back is mediated by individual, structural, contextual and programmatic factors.

The Foundation understands 'give-back' as a long-term non-linear practice, in line with a globalized economy in which people are increasingly mobile and in which social norms are in flux. While this understanding enables adaptability, there are a number of problems with the approach: alumni give-back is unstructured, informal, and is often not undertaken on a collective basis. Alumni give-back initiatives are not being monitored, measured, evaluated, nor brought into contact with one another and so a sustainable ethos of giving back is not necessarily being inculcated. Alumni are also struggling to engage in give-back that extends beyond the individual and community level and reaches a systemic level.

If the goal is to cultivate a network of young people committed to giving back and to continue to support their efforts then programme design and inputs must be instructive in fostering this ethos and facilitate opportunities for scholars to reflect on these inputs. There is also a need to pay greater attention to how the scholars' existing experiences and cultural understandings of give-back may be developed during their time in the scholarship programme in order to produce a cohort of scholars who will continue to engage in give-back even after their time in university has come to an end. Cultivating transformative leaders committed to giving back cannot be assumed, but must be thoughtfully and purposefully instilled, nurtured and supported. Universities have a role to play here, not just as sites of teaching and learning but as spaces where young people are conscientized by interaction with peers and community. Globally, the purpose of universities has been expanding beyond their traditional mandate of teaching, learning and knowledge production. This stems from the expectation that universities should pursue engaged scholarship and work with the communities within which they are located to address socio-economic challenges. Community engagement is what Dube and Hendricks (2023) refer to as the "third mission", while Fongwa (2023) calls it the "third function" of universities. Engaged universities (i.e. those fulfilling their third mission or function) encourage "civil and social responsibilities amongst students and enhance their sense of attachment and belonging to the community" by providing opportunities and resources for community engagement and giving back (Dube & Hendricks, 2023, p. 134). Although acknowledged as a third mission of university, community engagement as a pillar remains largely neglected in African universities but the scholarship programme under discussion consciously weaves this mission into their programming. In this light, this article presents a case study of the efforts made by a cohort of young graduates to move beyond self-interest and become agents of social, economic and political transformation in their contexts, arguing that these young people embody a strong 'social consciousness'. A term we use to encompass both give-back and transformative leadership. Findings from the ongoing research are shared to support our claims. We also make a case for how support for these transformative efforts can be better inculcated during time at university by providing example narratives from university partner institutions.

Understanding social consciousness: Give-back and transformative leadership

Giving back can be understood as "voluntary activities contributed to one's own ... community" (Weng & Lee, 2015, p. 511). Giving back is closely related to the concept of philanthropy, which may be defined as concerned with "the social relations of care expressed in a diversity of forms and acts of giving through which individuals or groups transcend their self-interest to meet the expressed or recognised needs of others" (Schervish & Havens, 1998, p. 600). So, for example, an alumnus in Rwanda said: "my wish is to not work on my own interests but thinking about the broader people" (Jacques, 31, Rwanda, Personal interview, 2022).4 Giving back may also be understood in the context of volunteering, which has been described as a more formalised way of producing a public good (Wilson, 2000). It may also be understood as a form of socially responsible activism, which, according to Jones (2002, p. 3), "involves many individuals taking actions in their everyday lives to help bring about what they see as a more socially and environmentally responsible world". Meanwhile, Andreoni (1990, 2006) proposes a "warm glow theory" for why people freely give to others who are lacking, suggesting that giving back is found in spaces where moral and cultural capital is acquired through solidarity, reciprocity, compassion and care for others.

These qualities align with the core principles of give-back embedded in many African beliefs and cultures characterised by the concept of ubuntu. This notion of give-back as an ethics of reciprocation, has been understood, articulated and practised by alumni over the years:

I am privileged in many ways compared to my folks in Ethiopia ... since I have more resources and better education, better connections, better opportunities, it isn't voluntary but mandatory for somebody like me to support people who are less fortunate ... (Habtamu, 26, Ethiopia, Personal interview, 2020)

Africa contributes to global notions of philanthropy through the African social philosophy of ubuntu, which is a way of being and a code of ethics (Aina & Moyo, 2013; Wilkinson-Maposa, 2016). Ubuntu reflects African people's understanding of the essence of being human, a humanity that is reflected in collective personhood and collective morality (Ngunjiri, 2016). Or as an alumnus in Rwanda said:

People have been made by others and supported by others. Without other people you can't be like who you are today. You have to give back to the community. That's my spirit. (Jaeden, 32, Rwanda, Personal interview, 2022)

Chuwa (2012, p. 150) reiterates this principle by suggesting that "a human person can neither be defined nor survive if separated from the society and the cosmos that enables that person's existence. It is a matter of justice to care for other humans, other lives and the non-living part of the cosmos".

At the same time, 'social consciousness' refers to the extent to which individuals and groups are aware of and concerned about social issues and the impacts these have on society (Freire, 1970; Goldberg, 2009). It is an awareness of the problems and challenges faced by different social groups and entails a commitment to working towards a more just and equitable society. Social consciousness can manifest in various forms, such as activism, volunteering, donating to social causes, and advocating for social justice. It also involves understanding and acknowledging the historical, cultural and systemic factors that contribute to social inequalities. Individuals who are socially conscious are typically aware of social issues, such as poverty, inequality and discrimination, and are committed to working towards social justice and positive change.

Closely linked is transformative leadership which aims at change in political, social and economic spheres in order to bring about social justice (Shields, 2010). In that sense, it has a moral aim that distinguishes it from other conceptions of leadership. In other words, transformative leadership is not content with changing the lives of individuals without also unearthing, problematising and dismantling the structures of power and privilege that prevent equity and freedom (Odora Hoppers, 2014; Shields, 2010) and that necessitate change or help in the first place. The concept of social consciousness encompasses the aims of the scholarship programme which selects potential scholars based on their experience of, and potential for, changing the world around them. Accordingly, emerging narratives of African give-back, as demonstrated by many alumni in the cohort, are about a progressively confident and well-informed assertion of Africans' capabilities to not only give but to also address root causes of social injustice on the continent (Kaya & Seleti, 2013). In this context, a present priority is to strengthen those capabilities, both during the university degree and after graduation.

Findings

Understanding alumni give-back

There is no one way to give back, "the possibilities are as diverse as the personalities, settings, and disciplines involved" (Chen & Hamilton, 2015, p. 8). As the years have progressed, a distinction can be drawn between 'informal' and 'formal' give-back. Informal give-back is characterised by small, responsive, usually once-off or single outcome driven actions, from which the immediate community benefits (i.e. family, friends, church, etc). Informal give-back can take the form of mentorship, career guidance, information sharing, tutoring, helping others adapt to university life, skills sharing and providing advice. It is often difficult to quantify the impacts of such informal arrangements and some alumni are reluctant to even call it giving back:

I haven't been involved much in give back projects... But the little that I do, I have a group of young people that I mentor ... provide guidance to them. If they need information, academic related, personal life, anything they just get in touch with me I wouldn't really call that a give back project. (Bianca, 30, Ghana, Personal interview, 2022)

Formal giveback is characterised by collaboration at an individual or institutional level; some kind of funding or material support; a documented plan/programme and sustained action. The number of alumni giving back in informal ways was greater than the number of those giving back in formal ways. Swartz makes a case that both these efforts should be lauded and that "the difference lies in the structured nature of these activities" (Swartz, 2021, p. 415). In other words, in Africa where resources are scarce, opportunities for structured or more formal arrangements "may not be as feasible as they are for those in the Global North" (Swartz, 2021, p. 415). Still alumni participate in give-back in their capacity and that usually begins with contributions to their immediate community. It was found that, over time, alumni expanded the social sphere in which they were giving back, moving from helping the nuclear/extended family, to engagement in broader community networks:

I have been helping at least four students, I've been paying their school fees, it's part of the give back activities in the county Mombasa it's not that expensive but their parents cannot afford that. (Charlotte, 29, Kenya, Personal interview, 2022)

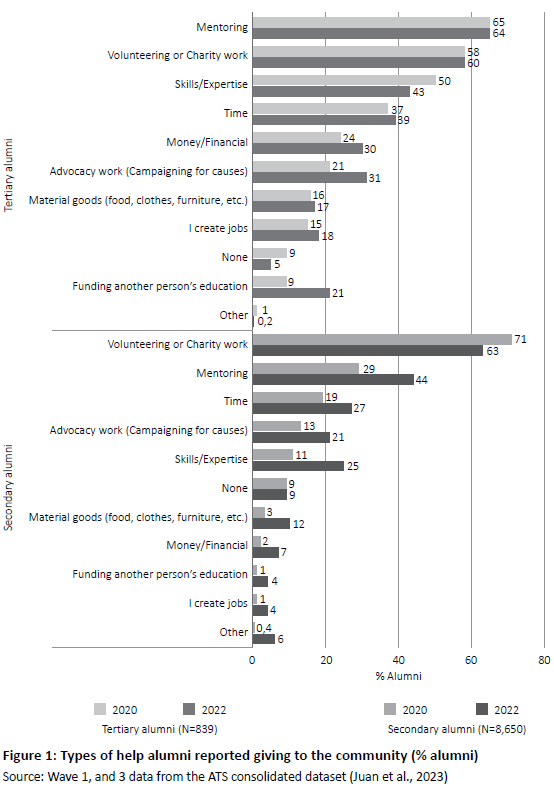

In 2020, the ATS asked alumni about the kind of help they give to their communities (see Figure 1). For secondary alumni, volunteering (71%), mentoring (29%) and giving time (19%) were the top interventions. Meanwhile among tertiary alumni, mentoring (62%), volunteering (57%) and offering skills or expertise (41%) were the highest.

In 2022 financial and material contributions increased for both secondary and tertiary alumni, with funding another person's education doubling in number for tertiary alumni. Half the alumni interviewed reported some form of sustained give-back since the study's inception and an ongoing commitment to giving back. These are young people who graduated as recently as 2020 or as far back as 2015 with more than a third (35%) of this cohort currently enrolled in postgraduate education. This ongoing commitment is reflective of most alumni's intentions and vision for give-back, with the vast majority (89% secondary alumni and 78% tertiary alumni) of those who participated in the 2020 ATS reporting that they would give back in the future. What is it that drives and keeps these givers dedicated to the charge?

What motivates alumni to give back?

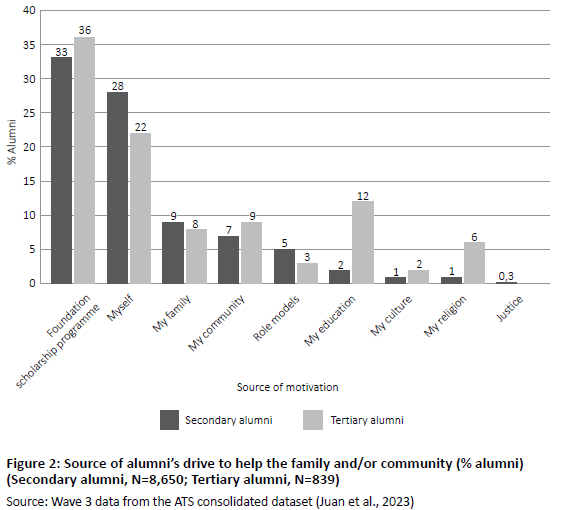

Those who give back might be motivated by a strong social conscience. Moscovici defines social conscience as the state of being fully aware of the problems that affect others and striving to mitigate these (1998). In the 2020 ATS, 97% of secondary alumni and 99% of tertiary alumni said they were aware of social problems in the community that needed to be addressed. We found that scholars and alumni's drive to give back was shaped by an innate ubuntu ethics, their social conscious, time in the scholarship programme, their personal obligations to their families and broader communities, their education, and less pointedly, a belief in social justice.

In the 2022 ATS, critically none of the secondary alumni and only 3% of the tertiary alumni named justice as a motivation for giving back. When key partners at universities were asked why justice seemed to rank so low as a motivation, they were generally unable to answer, since this value rarely featured in their give-back or transformative leadership inputs - which may be viewed as a missed opportunity during a fecund time in a student's life. The study also found that many alumni developed their passion for giving back over the course of their time at university, and through their interaction with inspiring peers. It is by working with one another, that scholars might strengthen their "capacity to recognize and analyze the systems and structures of a moving environment" and to conjure up ideas on how they might overcome these (Swartz, 2021, p. 398).

Give-back matures over time

By 2022, it was found that many alumni's understanding of give-back had matured, often through a process of trial and error. For example, Lizette from Uganda transformed a blog which she had initially established as a forum addressing gender inequality into a mentorship platform for young girls once she realized that the site had generated only a relatively limited impact in its original form. Lizette's transformation of the site was, in large part, inspired by an appreciation of the importance of collective action:

I know there are a lot of scholars who can be good mentors, so I'm thinking of riding on the peer mentorship model. (Lizette, 28, Uganda, Personal interview, 2022)

In starting alone, alumni are better able to course-correct from learnings and failures to develop their ideas to address systemic problems. But it is in working with others, that the extent of their impact can fully be realized.

Where in 2020 alumni lamented the lack of robust collaborative networks to better support their give-back activities and aspirations, in 2021 many began to work more collaboratively in their projects, with half aiming to undertake give-back projects at an institutional/systemic level in the future. It was found that over time, alumni had become more proactive in their give-back efforts, working within their personal ecosystems to bring about change. Accordingly, by 2022, it was useful to ask how alumni's give-back initiatives had been established. In most instances, projects began in partnership with classmates or peers, but seldom alone.

It started with a group of four of my classmates and we said we should go back to our schools to talk to these young people ... Two are fellow [scholarship programme beneficiaries], two are not [fellow scholarship programme beneficiaries]. (Clarence, 27, Diaspora, Personal interview, 2022)

If collaboration and developing the ability to work with others forms an essential foundation for working towards addressing social injustice, then what can be done to support this capacity?

In 2021 alumni spoke more intentionally about framing their plans to give back around their studies, career or their entrepreneurial aspirations. By 2022, a number of alumni made little to no distinction between their job, business, education and give-back efforts - choosing instead to view their livelihood or study as their contribution in the world. Given that one of the barriers to giving back encountered by alumni is work and other pressures, one way of encouraging activity in a more sustainable way would be to promote closer alignment between giving back and the work, business and educational activities already being undertaken by alumni. That way someone like Ezra from Uganda, who says, "ever since I left university, the kind of work that I've been doing has been so demanding, so the kind of give-back that we used to have in university has not been possible" (Ezra, 26, Uganda, Personal interview, 2022), would be able to think more instructively about the impact he can make within the confines of his demanding job.

Samantha articulates this point reflectively:

I have been trying within what I have been exposed to, for example, the research [in my field] ... If I invest in that over time, that is a give back because the research comes up and says okay, we have these problems in [my field] ... Then, that goes to the councils, they put in policies or whatever. That's also a form of giving back. I don't necessarily have to go to a soup kitchen every Saturday to be giving back. Sometimes, it has to be a more systemic thing. (Samantha, 26, South Africa, Personal interview, 2022)

In 2022, most of the alumni engaged in community, NGO or charity work said that their involvement was aimed at changing communities; a much smaller proportion said the aim was to produce change among individuals. An even smaller proportion - only 3% of secondary alumni and 11% of tertiary alumni - said they were aiming to produce systemic change. Although there was relatively little focus on systemic change, the data should be seen in the context of an overall increase in levels of social consciousness and give-back activity among the tertiary alumni. Those alumni who had managed to give back at the institutional/systemic level did so through their work. For example, Sahar from Uganda described the change she had implemented by shouldering additional responsibilities:

the eastern region of Uganda, it's more of like a patriarchal kind of setting. And like they don't believe women can do a lot of things and all that ... But then I stepped up [at work], like people trusted me and voted for me ... to be the women leadership council president . This is something that was not part of my contract but it's something I did voluntarily. And so I went ahead with my team and had to come up with a proposal or what I think can be changed I wrote a proposal which required around 50 000 USD per year . like a number of things that we could be able to change, to make sure that we create like a gender considerate environment. And I presented to the steering committee and they approved our budget and approved the council. So it's up and running So this budget is now an annual recurring budget and there are a lot of these things we changed, like the leave policies, the maternity, and a lot of other things like that affecting women. So a lot of these things, policies were written. And they were approved and I'm happy that they are putting them into practice And I'm happy that at least I created that change and people appreciated it and it has actually helped them. (Sahar, 27, Uganda, Personal interview, 2022)

Sahar studied Human Resources and they also works in the field. Their education coupled with work experience led to a heightened level of consciousness and expertise about a focused area. Individuals cannot care deeply and act effectively on every social and ecological problem they come across, but they can identify problems they feel are both important and which they have the agency and capacity to address effectively (Kotchoubey, 2018). Alumni rightly acknowledge that individuals, communities, institutions and systems are connected and that it is difficult to make a leap towards confronting systems without first addressing the issues that feel more proximal. Still insights from both interviews with alumni and university partners reveal the role partners play in fostering give-back engagement during scholarship, and their potential in aiding a network of active changemakers after graduation.

Nurturing social consciousness

Both the Foundation and university partners offer dedicated programming focused on developing scholars' capacities and dispositions as empathetic leaders with a sense of social consciousness. Partner data align with the findings discussed above, specifically that immediate community-based give-back features hugely in scholars' efforts, and that scholars are motivated and take charge of give-back interventions wherever possible.

[W]e really tried to instill that [the giving back concept overall] is a continuous process . it is not about waiting until you have completed your degree but finding ways to constantly give of your knowledge, impart what you have learnt, the skills that you are carrying now... (Institution Q, South Africa, Personal interview, 2020)

Scholars are being encouraged to play a more active role in the give-back interventions they undertake while part of the programme, and to see give-back as an opportunity to develop critical skills, networks and understanding of meaningful service to others. Some universities have used innovative ways to instil a culture of volunteering or community service, whether through requiring students to engage in a minimum number of service hours annually or certifying volunteer activities to give credit to students who undertake them. These provide a strong foundation for implementing partners to launch their own interventions from, as it creates an enabling environment with dual-sided support for give-back activities.

All partners also offer an annual or biannual service day where scholars undertake a collective give-back activity that they plan and run. Different partners observe other days of service, whether institutional, national, or international (such as Mandela Day). Scholars are also supported to work in groups on give-back projects, with the Foundation providing funding and partners overseeing a formal tracking and evaluation process. In this way, scholars are encouraged to think about their give-back efforts from an impact standpoint, while also being allowed the latitude to find more personal avenues for give-back that align with their individual experience.

In Ghana your give-back is not necessarily monetary. It is anything that you do to help somebody else in society ... They do it at home, they help siblings ... So to be able to formalise it and say whatever you're doing, record it to make it a formal activity, let's document it, let's share it. But this was sort of at odds with how people would naturally go about it. Internally we had our own way of trying to declutter and say look guys it is as simple as going to clean up at the beach near your campus, doing extra classes. Anything that you do to help society is part of give-back. But it has to be [conscious], it has to be organised and more importantly, if we can see how effective it is then it's even a double plus. (Institution F, Ghana, Personal interview, 2022)

The response by Institution F raises several important issues relating to how give-back is implemented across the scholarship programme. For one, while several partners agreed that there are many ways to give back and have social impact, the cultural motivations for giving back, that is, an innate ubuntu ethics, may compete with the format established across the partner ecosystem, which is focused on supporting scholars to engage in targeted give-back projects with demonstrable impact. Scholars may not conceive of certain actions as give-back or begin to interpret give-back actions in terms of an implicit hierarchy of value, based on perceptions of scale and impact.

The more recent programme shift towards give-back with systemic impact has reinforced the need for scholars to develop and demonstrate their capacities for give-back in ways that produce tangible results. This can foreclose the possibility of scholars developing innovative solutions through more ad hoc and process-focused activities. Moreover, it runs counter to the layered nature of scholars' give-back efforts after graduation, which are first and foremost concerned with establishing a sound, and often collective/familial, financial foundation from which a more robust future vision can be pursued. Continuing with give-back activities after graduation is thus where real challenges emerge, which include limited time or available finances, or lack of clarity about what to do or where to start. Because scholars are encouraged to work in groups on give-back interventions, their university and scholarship programme networks remain a key pathway through which they continue to engage in give-back after graduation. In some instances, these have yielded impressive collaborations:

One thing that I really like watching is that we have students from different disciplines such as engineering and business. And they sort of naturally come together to start different projects So, we have one group that's kind of a mix of global logistic students, as well as mechanical engineering students who have created a project a tomato growing operation in Ghana. And then it also has a training and youth development component. They've won thousands and thousands of dollars in different social venture competitions, but they've been able to scale it up . it's been really cool to watch. (Institution C, USA, Personal interview, 2020)

Scholars have been able to leverage the mobility and additional resourcing offered by the scholarship programme to design give-back projects that respond to problems, address local needs, and generate income for themselves and others. Diaspora scholars (those educated and living off-continent) are an unusual category because they are more likely to undertake planned, institutionalised outreach trips to Africa (often in their home countries), where they engage in extended give-back projects and cultivate relationships with specific partner organisations on the ground. Scholars at African universities also engage in outreach, but enter these activities through more localised connections, cultivating relationships through ongoing engagements and often over longer periods of time. From the data we can identify an emerging hypothesis that these relationships are durable specifically because of the reduced cultural and geographical distance between scholars at African universities and the communities they engage in give-back with. This suggests that scholars educated on the continent may have a more seamless experience in connecting give-back activities to their own contextually-located values and goals, given that they remain embedded within recognisable frameworks of social reciprocity.

Conclusion

The scholarship programme recruits beneficiaries who demonstrate a commitment to giving back. Still, individual factors alone do not influence decisions to give-back and motivations should be studied within social and political contexts (Joseph & Carolissen, 2019), for example, the global COVID-19 pandemic (Mahali et al., 2021), election violence or the humanitarian crises in Ethiopia. It was found that there were a number of factors that shaped the kind and extent of the influence that alumni were able to wield in the world, including their employment status, their age, and their networks, as well as issues of affordability, time and opportunity. In this context, it is appropriate that current university efforts to promote social consciousness should focus on practical ways of making a difference by developing agency, mentoring others, raising awareness, and collaborating to foster community development programmes.

The scholarship programme further nurtures and supports (through provision of resources and by encouraging collaborative network engagement) scholars' propensity for giving back during the funded degree making this the central business of the programme rather than a non-core activity as it is typically perceived (in favour of teaching and learning) at universities in Africa (Dube & Hendricks, 2023). Young people need both the inclination and the capacity to give, and that capacity is determined by the support one receives through, for example, "connection to charitable organisations (measured by social capital and volunteering) ... and human and financial capital variables" (Wang & Graddy, 2008, p. 28). Alumni really understand give-back in relation to their own scholarship and the way they apply it is through their own personal and collective resources, and through sharing the range of capitals acquired during the scholarship.

Motivation for giving back was found to be innate for many alumni. Even where giving may come at some sacrifice or personal cost, alumni described this as moral and social responsibility and as inherent to Africanness, in other words as an ubuntu ethics that "promotes the spirit that one should live for others" (Munyaka & Motlhabi, 2009, p. 69). As a result, most alumni intend continuing to give back in future, on an even larger scale. Alumni demonstrate that giving back, if it is done at all "will always be partial and incomplete" (Gupta & Kelly, 2014, p. 6). That giving back is not a 'purist endeavour' (Diver & Higgins, 2014) and it is often inconsistent (Sasser, 2014). Feminist and indigenous scholars remind us how "'giving back' should be a model of solidarity and movement building, not charity" (Gupta & Kelly, 2014, p. 6). In that regard, what has emerged from asking alumni about give-back is this notion that giving has a social ripple effect that can aid in the development of families, communities, and countries broadly. It is critical to conduct research of this nature if the future of the African university is to continue to pioneer engaged scholarship and the solutions needed to solve development and social justice problems.

Acknowledgements

This article was produced in the context of The Imprint of Education study that is conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa, in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of the foundation, its staff, or its board of directors.

Ethics statement

This study was approved the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee (Protocol No REC 6/19/06/19). All ethics protocols were followed by the researchers.

Potential conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding acknowledgement

The work reported in this article was supported by funding from the Mastercard Foundation.

References

Aina, T., & Moyo, B. (2013). The state, politics and philanthropy in Africa: Framing the context. In T. Aina & B. Moyo (Eds.), Giving to help and helping to give: The context and politics of African philanthropy (pp. 1-36). Amalion Publishing.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464-477. DOI: 10.2307/2234133. [ Links ]

Andreoni, J. (2006). Philanthropy. In L. A. Gerard-Varet, S. C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of giving, reciprocity and altruism (pp. 1201-1269). Elsevier.

Bono, J. E., Shen, W., & Snyder, M. (2010). Fostering integrative community leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(2), 324-335. DOI: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.010. [ Links ]

Chen, J. M., & Hamilton, D. L. (2015). Understanding diversity: The importance of social acceptance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(4), 586-598. DOI: 10.1177/0146167215573495. [ Links ]

Chuwa, L. T. (2012). Interpreting the culture of Ubuntu: The contribution of a representative indigenous African ethics to global bioethics (3540883) [Doctoral Dissertation]. Duquesne University. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [ Links ]

Diver, S. W., & Higgins, M. N. (2014). Giving back through collaborative research: Towards a practice of dynamic reciprocity. Journal of Research Practice, 10(2), 1-13. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/415/401 [ Links ]

Dube, N., & Hendricks, E. A. (2023). The praxis and paradoxes of community engagement as the third mission of universities. A case of a selected South African university. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(1), 131-150. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-high_v37_n1_a8 [ Links ]

Fongwa, S. (2023). Universities as anchor institutions in place-based development: Implications for South African universities engagement. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(1), 92-112. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-high_v37_n1_a6 [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Goldberg, M. (2009). Social conscience: The ability to reflect on deeply-held opinions about social justice and sustainability. In P. Villiers-Stuart & A. Stibbe (Eds.), The handbook of sustainable literacy (pp. 1-5) University of Strathclyde and the Centre for Human Ecology.

Gupta, C., & Kelly, A. B. (2014). The social relations of fieldwork: Giving back in a research setting. Journal of Research Practice, 10(2), 1-11. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/423/381 [ Links ]

Jones, E. M. (2002). Social responsibility activism: Why individuals are changing their lifestyles to change the world (Publication No. 3074757) [Doctoral dissertation] University of Colorado. ProQuest Dissertation Publishing. [ Links ]

Joseph, B. M., & Carolissen, R. (2019). Citizenship: A core motive for South African university student volunteers. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 14(3), 225-240. DOI: 10.1177/1746197918792840. [ Links ]

Juan, A., Xakaza, H., Mhlanga, N., & Lawana, N. (2023). Alumni Tracer Study consolidated dataset. Human Sciences Research Council.

Kaya, H. O., & Seleti, Y. N. (2013). African indigenous knowledge systems and relevance of higher education in South Africa. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 12(1), 30-44. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1017665 [ Links ]

Kotchoubey, B. (2018). Human consciousness: Where is it from and what is it for. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(567), 1-17. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00567. [ Links ]

Mahali, A., Swartz, S., & Wilson-Fadiji, A. (2021). 'Covid has created some other opportunities': Cautious optimism among young African graduates navigating life in a time of pandemic. Youth Voice Journal, ISSN (online), 2969.

Moscovici, S. (1998). Social consciousness and its history. Culture & Psychology, 4(3), 411-429. DOI: 10.1177/1354067X9800400306. [ Links ]

Munyaka, M., & Motlhabi, M. (2009). Ubuntu and its socio-moral significance. In F. M. Munyaradzi (Ed.), African ethics: An anthology for comparative and applied ethics (pp. 63-84). University of Kwazulu-Natal Press.

Ngunjiri, F. W. (2016). "I am because we are": Exploring women's leadership under Ubuntu worldview. Spiritual and Religious Perspectives of Women in Leadership, 18(2), 223-242. DOI: 10.1177/1523422316641416. [ Links ]

Odora Hoppers, C. (2014). Wounded healers and transformative leadership: Towards revolutionary ethics. In K. Kondlo (Ed.), Perspectives on thought leadership for Africa's renewal (pp. 23-36). Africa Institute of South Africa.

Sasser, J. S. (2014). The limits to giving back. Journal of Research Practice, 10(2), Article M7. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/397/348 [ Links ]

Schervish, P. G., & Havens, J. J. (1998). Embarking on a Republic of benevolence? New survey findings on charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 27(2), 237-242. DOI: 10.1177/0899764098272007. [ Links ]

Shields, C. M. (2010). Transformative leadership: Working for equity in diverse contexts. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(4), 558-589. DOI: 10.1177/0013161X10375609. [ Links ]

Swartz, S. (2021). Navigational capacities for Southern youth in adverse contexts. In S. Swartz, A. Cooper, C. M. Batan & L. Kropff Causa (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Global Youth Studies (pp. 398-418). Oxford University Press.

Wang, L., & Graddy, E. (2008). Social capital, volunteering, and charitable giving. Voluntas, 19(1), 23-42. DOI: 10.1007/s11266-008-9055-y. [ Links ]

Weng, S. S., & Lee, J. S. (2015). Why do immigrants and refugees give back to their communities and what can we learn from their civic engagement? Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(2), 509-524. DOI: 10.1007/s11266-015-9636-5. [ Links ]

Wilkinson-Maposa, S. (2016). African philanthropy: Advances in the field of horizontal philanthropy. In S. Mottiar & M. Ngcoya (Eds.), Philanthropy in South Africa: Horizontality, ubuntu and social justice (pp. 169-184). HSRC Press.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215-240. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215. [ Links ]

Received 30 June 2023

Accepted 24 October 2023

Published 14 December 2023

1 We use 'scholars' to refer to students currently being funded by the scholarship programme. We use 'alumni' to refer to recent graduates of the scholarship programme.

2 Tertiary alumni received scholarships from the Foundation to pursue undergraduate or postgraduate qualifications.

3 Secondary alumni received scholarships from the Foundation to complete secondary school.

4 The label used here denotes the study participant's pseudonym, followed by their age, their country of citizenship and the year the interview was conducted.