Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa

versão On-line ISSN 2307-6267

versão impressa ISSN 2311-1771

JSAA vol.11 no.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i1.4206

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Harnessing student agency for easier transition and success: The role of life coaching

Disaapele MogashanaI; Moses BasitereII; Eunice Ndeto IvalaIII

IUniversity of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: disaapele.mogashana@up.ac.za.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-6300-0206

IIUniversity of Cape Town, South Africa. Email: Moses.Basitere@uct.ac.za. ORCid: 00000002-1258-5443

IIICape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. Email: ivalae@cput.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-5178-7099

ABSTRACT

Research on student support in the global North indicates possible benefits of life coaching interventions in improving students' persistence and well-being. There is emerging research on life coaching interventions and their potential benefits in the South African higher education context, but empirical evidence is scarce. We report results from a longitudinal study that investigated a life coaching intervention to support students. The objective of the intervention was to harness students' agency proactively by equipping them with skills to improve their academic and non-academic lives. Data were gathered through one-on-one semi-structured interviews with ten students who had participated in the intervention. We used Archer's social realist concepts of structure and agency as our theoretical framework. The results indicate that the life coaching intervention enabled students to mediate academic and non-academic constraints. Concerning academic constraints, it helped students manage the transition from high school, including adjusting to a new workload, time management, learning to collaborate with their peers, and dealing with experiences of failure. Concerning non-academic constraints, the life coaching intervention helped students clarify their goals, increase their self-awareness, cope with negative emotions, and boosted their self-confidence and resilience.

Keywords: Life coaching, student agency, student success, student support, engineering education

RÉSUMÉ

Les recherches sur le soutien aux étudiants dans les pays du Nord montrent les avantages potentiels des interventions de coaching de vie en termes d'amélioration de la persévérance et du bien-être des étudiants. Des recherches émergentes portent sur les interventions de coaching de vie et leurs avantages potentiels dans le contexte de l'enseignement supérieur en Afrique du Sud, mais les preuves empiriques sont encore rares. Nous présentons les résultats d'une étude longitudinale portant sur une intervention de coaching de vie visant à soutenir les étudiants. L'objectif de l'intervention était de mobiliser de manière proactive l'agentivité des étudiants en les dotant de compétences leur permettant d'améliorer leur vie académique et non académique. Les données ont été recueillies lors d'entretiens individuels semi-structurés avec dix étudiants ayant participé à l'intervention. Nous avons utilisé les concepts réalistes sociaux de structure et d'agentivité d'Archer comme cadre théorique. Les résultats indiquent que l'intervention de coaching de vie a permis aux étudiants de mieux gérer les contraintes académiques et non académiques. En ce qui concerne les contraintes académiques, elle a aidé les étudiants à mieux gérer la transition du lycée vers l'université, notamment en s'adaptant à une nouvelle charge de travail, en gérant mieux leur temps, en apprenant à collaborer avec leurs pairs et en faisant face à des expériences d'échec. En ce qui concerne les contraintes non académiques, elle a aidé les étudiants à clarifier leurs objectifs, à accroître leur conscience de soi, à faire face aux émotions négatives et à renforcer leur confiance en soi et leur résilience.

Mots-clés: Coaching de vie, agentivité des étudiants, œuvres estudiantines, réussite étudiante, services étudiants, soutien aux étudiants, éducation en ingénierie.

Introduction

The expansion of higher education in South Africa has continued steadily for close to three decades since the dawn of democracy. According to the Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) 's 2000 to 2016 cohort studies, enrolments for first time entrants rose from 98,095 in the year 2000 to 141,850 in 2016 (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2019). With widening student access, higher education institutions (HEIs) struggle to complement student access with student success (Schreiber et al., 2021; van Zyl et al., 2020). According to the Department of Higher Education and Training report, although there have been some improvements in student success, the overall throughput rates of students remain low, with just over 50% of students entering higher education dropping out, contributing not only to financial wastage, but to unrealised aspirations (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2019).

The high dropout rates remain problematic in the South African context, where the academic success of students from disadvantaged backgrounds continues to play a significant role both in achieving the redress and developmental agenda of the country, as well as fostering upward social mobility of graduates (Case et al., 2018; Statistics South Africa, 2017). The biggest challenge remains in the first year, and this is the level at which most student transition interventions have been explored and implemented (McConney, 2021). Many of these interventions have focused on students' transition from high school into higher education. They have contributed significantly to the maturity of the first-year experience literature in South Africa (Nyar, 2020). Some of the interventions that are currently being explored and implemented include, for example, those that focus on peer mentoring programmes (McConney, 2021). Some are exploring different academic advising models in their institutional contexts (Schoeman et al., 2021; Tiroyabone & Strydom, 2021; van Pletzen et al., 2021). Other studies are exploring different ways of enhancing students' well-being and harnessing student agency (Mogashana & Basitere, 2021; Terblanche et al., 2021). And finally, others have adopted a more comprehensive institutional approach using data-informed strategies to effectively provide students with academic and non-academic support in a collaborative way that enables student success (van Zyl et al., 2020). While much of the current research predominantly covers student transitions at the entry level, Schreiber et al. (2021) call for increased "context-relevant" and "high impact" support interventions research that expands the knowledge base on student transitions into and through to the senior years in their studies. We aim to contribute to answering this call.

In this article, we report findings drawn from a qualitative study conducted four years after a group of extended curriculum programme (ECP) in chemical engineering students participated in a small group life coaching intervention at a university of technology. We investigated how the life coaching intervention had influenced students' agency as they navigated their way through university from the first to the final year of their studies for the diploma in chemical engineering. We provide a brief literature review on life coaching as an intervention in higher education institutions. We then briefly outline the conceptual framework of structure and agency (Archer, 1995, 2003) that we use to frame our findings. Next, we present the methodology that guided the study, followed by the results. We discuss key findings and limitations and conclude by providing avenues for future research.

Literature review

Life coaching

Broadly, life coaching may be defined as "a collaborative, solution-focused, result-orientated and systematic process in which the coach facilitates the enhancement of life experience and goal attainment in the personal and professional life of normal, nonclinical clients" (Grant, 2003, p. 254). Life coaching is a solution-focused practice rooted in positive psychology, and it explores and harnesses a client's strengths. According to Grant (2003), key parts of life coaching are the attainment of goals, personal development, increased self-reflection, and enhanced mental health in nonclinical populations. Extending this definition to a nonclinical student population, academic coaching entails collaboration between a student life coach, often referred to as an academic coach, and a student, and it focuses on the clarification of the student's academic, personal and professional goals and a guided process of attaining them (Capstick et al., 2019). For students, the primary outcome of this collaboration, as Capstick et al. (2019) indicate, is the completion of an academic qualification.

Apart from helping students clarify their goals, the coach's role includes guiding students to overcome internal and external barriers to their success, advising, keeping a student accountable and helping them learn how to self-reflect and self-regulate their behaviour. For example, obstacles that often hinder students' academic success include poor time management, fear of failure, poor stress management and burnout, and procrastination (Mogashana & Basitere, 2021). The student life coach employs various techniques to assist students in overcoming these challenges. Despite the possible benefits that life coaching interventions may bring to the context of higher education, there is a general lack of empirical research on student life coaching interventions (Capstick et al., 2019; Howlett et al., 2021; Lefdahl-Davis et al., 2018). Most interestingly, much of the written literature on student life coaching in higher education is based on studies from the United States and is mainly based on quantitative studies. We will provide a brief review of some of these studies next.

Recent studies of student life coaching in higher education

In their recent study that explored the effects of academic coaching on fostering college students' development of self-regulated learning skills, Howlett et al. (2021) used a randomised controlled trial design on three groups of students who had not been exposed to academic coaching. They found that the life coaching intervention increased metacognition in the treatment groups, and this was found to be the case for both the students coached face-to-face and those coached online. The study by Capstick et al. (2019), which investigated the use of life coaching to support "at-risk" undergraduate students, found that students who had been coached were more likely to be retained and to proceed to other semesters than students who had not been coached. In another study that focused on the use of weekly life coaching to support students with disabilities in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) programmes at three institutions, Bellman et al. (2015) found that life coaching had improved students' motivation to succeed and improved their self-confidence. Furthermore, it had increased skills such as time management, stress management, prioritisation, and note-taking. To contribute to the already noted benefits of life coaching, the study by Lefdahl-Davis et al. (2018) found that life coaching contributes to student's satisfaction with the choice of an area of study, helps them become aware of and be in alignment with their values and their connection to their life purposes. A study by McGill et al. (2018) argued for the use of life coaching as a way of supporting marginalized (in this case, students of colour) students' academic journeys because it "improves the student's sense of belonging, self-efficacy, and ultimately, their success." (p. 23). Lastly, and in the context of higher education in South Africa, a study by Mogashana and Basitere (2021) found that life coaching helped students not to drop out of their studies, deal better with experiences of failure and improved their academic performance.

The reviewed studies suggest that the use of life coaching in student populations may improve metacognition, well-being, motivation to succeed, self-confidence and other skills that students need to succeed academically and in life and reduce the chances of dropping out. Although the literature reviewed is limited due to a lack of empirical studies in the field, what was evident, at least at the time of the review, was that apart from one study, no other recorded empirical studies investigated students' experiences of the use of life coaching interventions in higher education in South Africa. It is this gap in local literature and the gap in the qualitative studies literature globally that this study aims to contribute. Next, we present the conceptual framework that guided our research.

Structure and agency: The interplay between potential structural and cultural constraints and enablements and students' personal projects

An investigation into how the life coaching intervention within a programme at a university may have influenced students necessitates an examination of the interaction between the properties of social structure and human agency. We employ some concepts from the social realist theory, structure, culture and agency, the morphogenetic approach (Archer, 1995, 2003). Key to Archer (1995)'s morphogenetic approach is the understanding that structure and agency are distinct strata of reality with distinct properties that are irreducible to one another. These properties emerge from previous interactions in which structure and agency shape future outcomes. The morphogenetic approach allows a temporary separation between the respective emergent properties of structure, culture and agency to examine the interplay between them. According to Archer (2003), examining structure (social relations that include positions, roles, and material resources), culture (ideas and propositions) and agency (including reflexivity, intentionality, and deliberations) entails examining the interplay between their respective emergent properties and determining how each has changed over time. The study from which data presented in this article were derived traced how students' sense of agency was influenced by a life coaching intervention, a part of the social structure and culture they encountered upon commencing their undergraduate studies in chemical engineering.

The process of tracing how agency was influenced may be described as follows: structural and cultural emergent properties of the context in which students encountered predate them and remain dormant until they are activated by the agents, both individual and as a collective, in search of their own ends (Archer, 1995). According to (Archer, 2003), human beings have things they care about the most; Archer refers to these as their "ultimate concerns". Human beings then devise certain courses of action to achieve their ultimate concerns, which are what Archer (2003) calls "projects". While human beings are in the process of pursuing their projects, they encounter and activate the emergent properties of structure and culture that then act as either "constraints" (or challenges, obstacles, impingements) or "enablements" (or empowerment, assistance). These potential constraints and enablements remain dormant and may remain unexercised until agents' pursuit of personal projects activate them.

Archer (2003) posits "reflexivity" as the most important personal emergent property that allows human beings to mediate the structural and cultural emergent properties they encounter while pursuing their projects. As human beings, our ability to hold internal conversations, consider ourselves in relation to external circumstances, and choose to act in particular ways makes us active agents. Our power to hold internal conversations individually (through our reflexive deliberations) or to devise collective action through corporate agency, is how agency is transformed and reshaped in relation to the conditioning influences of structure and culture. Considering the concepts outlined above, we asked the following theoretical research question: "How has having participated in the life coaching programme influenced students' agency?" Therefore, this article aims to report the findings of our qualitative investigation into the role of a small group life coaching intervention in harnessing students' agency over time. The following section outlines our methodology in answering the stated research question.

Methodology

We followed a case study methodology as it enabled us to explore "how" life coaching influenced the participants within the context of an ECP in chemical engineering, our unit of analysis, over four years (Yin, 2009). The strength of a case study is that it allows us to do an in-depth investigation within a particular context; however, it has often been criticised for poor transferability to other contexts. We intend to provide all the necessary detail to facilitate the application of the insights drawn from this case study in other contexts.

Research context

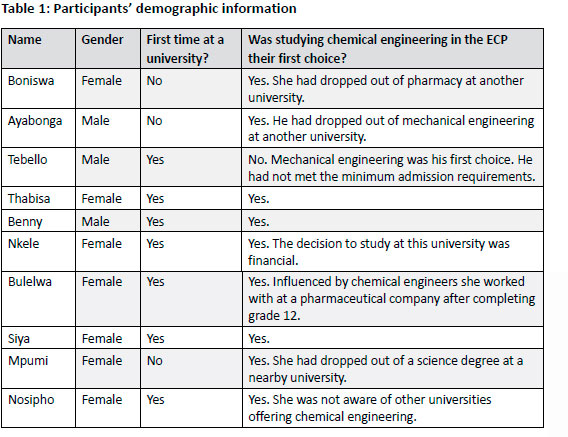

The study was conducted with students who had been part of the ECP in chemical engineering at a university of technology. During their first year in 2018, the ECP implemented a pilot life coaching intervention to support its students with psychosocial issues that often affected their academic performance. The life coaching intervention occurred on weekends. Each participant was invited, together with five to seven others, to one entire Saturday and Sunday face-to-face group life coaching programme. The selection criteria included their academic performance in their first class tests and information that students provided in the background information questionnaire that they had completed at the start of the year. The weekend programme was followed by ongoing support from the coach via WhatsApp messaging social media. This article's findings reveal how the life coaching intervention influenced the lives and academic journeys of students whose participation began four years ago. At the time of collecting data for this article, only 10 of the 36 students who had participated in the life coaching programme and were still registered at the university (regardless of whether they were in their final year or not) agreed to participate in our follow-up investigation. All ten are in the final year of their studies. Table 1 below provides important information about each of the 10 participants. Participant data were anonymised using pseudonyms.

Data gathering and analysis

Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with each of the 10 participants. These interviews were conducted by the third author, who had not been directly involved with either the teaching or the coaching of the participants. Participant students completed an informed consent form. The interviews were conducted through audio-recorded Microsoft Teams sessions and were later transcribed and saved using students' pseudonyms. Important to the interview schedule was the breakdown of the overall question "How has having participated in the life coaching influenced your undergraduate journey?" into sub-questions that covered a range of academic and non-academic "challenges" and "the solutions". The breaking down of interview questions in this way was so that data could be analysed using content analysis guided by Archer's (1995) "constraints" and "enablements" in the development and harnessing of human agency.

Transferability and credibility

A case study design was employed. A case study aims to provide an in-depth understanding of a case (Yin, 2009), and establishing trustworthiness has its limitations, such as the non-generalisation of the findings. Although this study's findings are not transferable to ECPs in other engineering departments across institutions with similar contexts, we hope that insights from this study can inform practice in these institutions. On the aspect of credibility, the interview transcripts were read in detail by each author, and the understanding and interpretation of each participant's narrative were discussed in detail. We hope more programmes will explore our efforts in their own contexts.

Ethical clearance and researcher positioning

This article forms part of a more extensive pilot study of which the faculty of engineering at the university where this study took place provided ethical clearance. It is worth noting that the first and second authors were involved as the students' life coach and mathematics lecturer, respectively, during the year in which the intervention was implemented. However, the potential negative impact of their involvement was mitigated by interviews conducted by the third author, who had not interacted with the participants in the capacities of either lecturer or life coach.

Results

The life coaching intervention aimed to equip students with skills that might harness their agency and improve their ability to overcome academic and non-academic constraints as they navigated their way through their studies. To establish how having participated in the life coaching intervention had influenced students, the results are presented using the two categories that emerged from data analysis. We start by presenting the academic constraints students experienced in the first and subsequent years and how what they learned during life coaching enabled them to mediate these. We then present the non-academic constraints and how students mediated them over the years of undergraduate studies.

Academic constraints and how life coaching enabled students to mediate them

All ten participants reported having experienced academic constraints at the start of their chemical engineering studies. The most notable constraint that affected them academically was managing the transition from high school or another university. For example, Boniswa, having been at another nearby university, and with her nature as "not being social", found it difficult to adjust and seek help from other students when she struggled to use the digital systems at the university. But she indicated that having participated in the life coaching programme helped her to be more social:

I want to believe that now I am a social person. I can be able to communicate with other people without being afraid of what other people are going to think. I am now able to express myself better. (Boniswa's interview)

The second constraint that students experienced in transitioning entailed managing increased workload, pacing in courses, difficulty in understanding some lecturers and time management. Thabisa shared her experience of struggling with time management and how coaching helped her resolve it:

It[the challenge] was more of not studying on time and not doing time management, not having a good timetable to keep up on my schoolwork... When we were being coached, I think I had to come up with a nice plan to keep up with my academics. (Thabisa's interview)

Knowing how to manage time was not only important for students in their first year but became an enablement for some in managing the transition to remote learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. Mpumi shared her challenges during with remote learning, which started during her third year, and how the skills to manage her time and communicate with classmates she had learned during coaching helped her:

I was able to manage time, whenever I didn't have data to attend class, I had to manage my time and make a timetable to say ok this time is for catch up and I had to ask people to help me with what was done in class It[coaching] really helped me with time management and communication. (Mpumi's interview)

Some students admitted that they found it challenging to collaborate with other students at first, making it difficult to find help with the modules. At first they tried to resolve their academic challenges on their own, but life coaching taught them the value of getting support from their peers. Benny related how he overcame this constraint:

I used to be a selfish person and a person who was always on my own, a person who believes that he can do everything by himself but through life coaching I developed a lot of things: how to share, how to assist other people, how to even ask some help from other people because I'd say I used to have pride and this pride had so much negative impact on my life - even academically. (Benny's interview)

Furthermore, some students indicated that the most challenging part of managing their transition to university was learning how to deal with failure and build resilience. Tebello shared his experience:

Academically it was dealing with failure ... What I've learned is that most of the circumstances or situations I found myself in I can take myself out of them and the influence that I had on my academics is that whatever challenges that I came across, maybe let's say for example a failure, I knew that I could always bounce back from a failure because it is part of that process I was in. So it [coaching] gave me that skill of resilience I'd say. (Tebello's interview)

Apart from constraints that students experienced that directly impacted their academics, there were other psychosocial constraints that life coaching seems to have helped them navigate. They are presented next.

Non-academic constraints and how life coaching enabled students to mediate them

As human beings making their way through life, some students are often unclear about their goals. The results indicated that for some, life coaching helped them clarify the direction their lives were taking and set goals for their lives. Thabisa, for example, having learned about goal-setting during life coaching indicated that she wanted to start an NGO in her community after her studies. She found that being clear about her goal helped her find strength during a challenging time in her second year of study when she was struggling with one of her modules:

That time [in second year] I did talk with my coach on WhatsApp that I was having difficulty with the module and I think it did help me overcome the challenge that I was having and I pulled myself and still continued because I knew that at the end of the day I have a goal that I need to achieve . So I think my next goals and achievements, or the foundation of it, really came from the coaching because at first I didn't know what it is that I want to do when I get to my third year but now I have a picture of what I would want to do. (Thabisa's interview)

In another example, Boniswa indicated that coaching enabled her to focus and prioritise things that matter to her:

I was able to prioritise the things that are important to me. I was able to do research about my academics to make sure that I pass. I was able to plan ahead when studying and I was able to do that through coaching. (Boniswa's interview)

The results also indicate that life coaching may have enabled some students to improve their self-awareness and resilience. Ayabonga, for example, described his experience as follows:

We were given the skill of self-awareness. The coach always reminded us that we can always achieve everything that we put our minds to ... Another skill would be problem-solving and decision-making. She [the coach] had a positive impact in the way I think and the way I present myself and also the way that I judge situations. (Ayabonga's interview)

The self-awareness and the ability to reflect upon their circumstances and make decisions about possible actions helped Ayabonga during a very challenging time in when he was confronted by his brother's untimely death.

You don't know when death is going to hit your loved one. I was so numb about it but I managed to come back to my senses. I told the coach about it and from that moment she was there for me ... Had she not been there, I mean I was considering taking a gap year or to just stop and deregister or finish the semester and come back the other year. (Ayabonga's interview)

Siya also lost a sibling, her younger brother, at the end of her first year. She indicated that the experience of grief threatened to affect her second year, but that she had learned a lot about herself and her emotions and how to express them during coaching and this helped her begin to process her grief. She said that although she did not perform as well in her second year as she did in her first year, she was grateful that her support helped her complete her courses that year.

As with Ayabonga and Siya, other students also learned how to understand and deal with negative experiences and emotions. For example, Nkele indicated that she had undergone parental separation back home during her first year. She had been robbed on campus while walking from the library, an experience she found traumatic that year. Nkele reported that, immediately after the robbery, she did not have anyone to talk to but that having access to and contacting the life coach on WhatsApp helped her to "calm down". Apart from overcoming this unfortunate incident, Nkele indicated that life coaching contributed to her understanding of her emotions:

Dealing with my negative emotions and taking care of my mental health. I think that's what I got to learn the most about through life coaching. I believe that if I am ok emotionally and psychologically, then I can be able to focus on my academics So having been made aware of how I can face my emotions and fulfil myself as a whole made it easier for me to balance my studies because you definitely cannot focus on your studies if you as a person as a whole are not doing ok. (Nkele's interview)

Additionally, the life coaching intervention enabled students to develop self-confidence as all of them mentioned some aspects of their confidence had improved. Bulelwa, for instance, said that when she arrived at university, after having worked at a pharmaceutical company immediately after matriculation, she was not confident that she would succeed primarily because she had struggled with mathematics in high school. Bulelwa had struggled to make friends as she did not have the confidence to do so, but coaching had helped her with it:

I am one person who doesn't know how to ask for help. I don't know how to reach out to people. So it[coaching] helped me because I am able now to ask for help if I am struggling with something. I believe in myself more than anything because I had zero confidence in myself, especially in my academics, but now these past few years because of that session and because of the things we were taught there, the things that [the coach] taught us, I am in a place where I am confident. That I can do anything if I put my mind in whatever I want to do -1 can do anything. As long as I am willing to put in the work and the effort and know when to ask for help. (Bulelwa's interview)

Importantly, life coaching seemed to have enabled all the participants to cope better during the remote learning period and persistent lockdowns resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic. Whether it was Nkele, who had no space dedicated to study at home, as she shared a room with her siblings, and public libraries were then closed, or Benny, whose fears about the possible death of his family members led to a temporary loss of motivation to study, or Bulelwa, who had to deal with the challenging times of extreme isolation and loneliness and having to live with and face herself daily. Coaching had enabled them with the tools and skills that they used to navigate this potentially constraining period. It was under these unprecedented and unpredictable conditions that they drew on the skills that they gained during life coaching, demonstrating their ability to persist despite the odds.

Discussion

Higher education institutions in South Africa continue to explore academic and non-academic interventions that support students' transitions and promote student success. Our aim in this study was to investigate the use of one such intervention.

The positioning of students within the ECP when they arrived at the university exposed them to the influences of both structure and culture, and their associated emergent properties. The emergent properties of structure and culture, when activated by students seeking to pursue their personal projects of attaining a qualification, provided students with potential constraints (challenges) and enablements throughout their undergraduate studies. To mediate the potential constraints of structure and culture, students exercised their agency by holding reflexive deliberations and acting collectively to provide each other support. Our aim, therefore, was to investigate how having participated in the life coaching intervention during their first years had influenced students' agency during the transition from school and other universities and through to the final year of their studies in chemical engineering.

The results indicate that students encountered various academic and non-academic constraints during their four-year educational journeys, and that having participated in the life coaching intervention had acted as an enablement or had harnessed their agency successfully by providing them with the skills to mediate the constraints. Concerning academic constraints, the findings indicate that, first, in managing the transition from high school to university, students had to adjust to the new environment and increased workload. We found that having participated in the life coaching enabled them to learn how to manage their time effectively, process their experiences of failure, and collaborate better with their peers. These findings align with the findings by Mogashana and Basitere (2021), who found that life coaching had empowered students' agency with skills such as time management, dealing with failure, collaborating with peers and these skills helped them to mediate the potentially constraining influences of structure at the university during their first year. However, where the present study differs is in that the students drew on these skills to overcome constraints not just in their first year, but that the life coaching intervention had a long-term influence throughout their undergraduate studies. Considering that these were students who had entered the university through the ECP and had therefore not met the minimum requirements for enrolment in the mainstream programme, the fact that they were now in their final semester of the final year in minimum time indicates their strong agency to persist and succeed. The strong commitment to persistence resonates with the findings of the studies by Capstick et al. (2019), who found that life coaching enhances the chances of retaining "at-risk" students and reduces the chances of dropping out. We also found, as with Bellman et al. (2015)'s study which showed that students who had been coached had better time management and stress management skills to succeed in STEM programmes, that the life coaching intervention had equipped the participants with the skills to manage their time and stress successfully and independently. This finding indicates that participants' agency may be harnessed to navigate potential structure and culture constraints better.

Concerning non-academic constraints, we found that the intervention influenced students' agency by enabling them to be clearer about their future goals and aspirations. Life coaching improved the students' self-confidence in their abilities to achieve their goals. Lefdahl-Davis et al. (2018) report similar findings about students' satisfaction with their choices of study and their connection to students' life purposes; students were motivated to succeed and were looking forward, with confidence, to the next chapters of their lives once they had completed their studies. Moreover, results showed students' increased agency in that they had a greater sense of self-awareness and the ability to handle negative emotions effectively, which is paramount to students' well-being, and, ultimately, their success (McGill et al., 2018). The current study made two more significant findings. First, the results indicate the life coaching intervention has prolonged benefits that continue beyond the year of intervention. Although the participants were coached in the first year, the intervention results suggest that this "enablement" continued to be invaluable to them throughout their studies. Second, the findings showed that life coaching had harnessed students' agency to cope with their studies and lives during one of the most stressful periods of this generation - the Covid-19 pandemic. The results have shown that students had to overcome various constraints, including learning online and dealing with isolation during hard lockdowns. They had the agency to reach out to one another, collaborate through social media platforms such as WhatsApp and encourage each other to persist. These students were able to exercise their agency, both individually and collectively, to show resilience and dedication to their personal projects, something that they reported had been influenced by, among other things, their participation in the life coaching intervention in their first year. As the results indicated, all the positive influences on students' agency were experienced during and beyond the year of the life coaching intervention.

We argue, therefore, that the use of a life coaching intervention in supporting students may be invaluable and, based on the findings of this study, it could be one of the "high impact" interventions that Schreiber et al. (2021) call for.

Conclusion

This article reports findings derived from a qualitative study that investigated how having participated in a life coaching intervention in the first year at a university had influenced students' agency. Overall, the results indicated that the life coaching intervention harnessed students' agency, which enabled them to overcome potentially constraining academic challenges such as transitioning from high school, adjusting to increased workload, time management, dealing with failure and learning to collaborate with their peers. Concerning non-academic challenges, the results revealed life coaching harnessed students' agency by empowering them to clarify their goals, increased their self-awareness, helped them deal with their negative emotions effectively, improved their self-confidence, and enabled them to be more resilient in dealing with the challenges they faced during the Covid-19 pandemic. The findings highlighted the importance of the life coaching intervention for students, not only as a potentially effective support intervention at the first-year level but as an intervention with the potential of supporting them throughout their undergraduate studies and on life issues beyond their studies.

This article contributes to the literature exploring student transitions in the South African higher education context and to the scant empirical literature globally concerning the use of life coaching for supporting students in higher education. The limitation of data presented herein is that, although there was a significant number of students from the original cohort, some a year or two behind, only those who had reached the final year chose to participate in the study. This limits our findings, as we do not have views of students who repeated some levels of study. We recommend a study including both students who repeated and those who had not repeated classes for richer data on the impact of the life coaching intervention. We further recommend research into the use of life coaching as a holistic student transition support intervention in different university contexts. Inter-institutional collaborative study within similar contexts and intra-institution case studies within different faculties and departments may provide far-reaching understandings of the possible impact that life coaching interventions may have in reducing dropout rates and improving student experiences and success in higher education.

Ethics statement

All ethics protocols were observed by the authors. Ethical clearance was provided by the Cape Peninsula University of Technology's Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment.

Potential conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding acknowledgement

No funding was received for this study.

References

Archer, M. S. (1995). Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge University Press.

Archer, M. S. (2003). Structure, agency and the internal conversation. Cambridge University Press.

Bellman, S., Burgstahler, S., & Hinke, P. (2015). Academic coaching: Outcomes from a pilot group of postsecondary STEM students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(1), 103-108. [ Links ]

Capstick, M. K., Harrell-Williams, L. M., Cockrum, C. D., & West, S. L. (2019). Exploring the effectiveness of academic coaching for academically at-risk college students. Innovative Higher Education, 44(3), 219-231. [ Links ]

Case, J. M., Marshall, D., McKenna, S., & Mogashana, D. (2018). Going to university: The influence of higher education on the lives of young South Africans (Vol. 3). African Minds

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2019). Post-school education and training monitor: Macro-Indicator Trends. Department of Higher Education and Training.

Grant, A. M. (2003). The impact of life coaching on goal attainment, metacognition and mental health. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 31(3), 253-263. [ Links ]

Howlett, M. A., McWilliams, M. A., Rademacher, K., O'Neill, J. C., Maitland, T. L., Abels, K., Demetriou, C., & Panter, A. (2021). Investigating the effects of academic coaching on college students' metacognition. Innovative Higher Education, 46(2), 189-204. [ Links ]

Lefdahl-Davis, E. M., Huffman, L., Stancil, J., & Alayan, A. J. (2018). The impact of life coaching on undergraduate students: A multiyear analysis of coaching outcomes. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 16(2), 69-83. [ Links ]

McConney, A. (2021). Facilitating adjustment during the first year. In M. Fourie-Malherbe (Ed.), Creating conditionsfor student success (pp. 35-57). African Sun Media.

McGill, J., Huang, L., Davis, E., Humphrey, D., Pak, J., Thacker, A., & Tom, J. (2018). Addressing the neglect of students of color: The strategy of life coaching. Journal of Sociology and Christianity, 8(1). [ Links ]

Mogashana, D., & Basitere, M. (2021). Proactive student psychosocial support intervention through life coaching: A case study of a first-year chemical engineering extended curriculum programme. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 9(2), 217-231. [ Links ]

Nyar, A. (2020). South Africa's first-year experience: Consolidating and deepening a culture of national scholarship. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 8(2), ix-x. [ Links ]

Schoeman, M., Loots, S., & Bezuidenhoud, L. (2021). Merging academic and career advising to offer holistic student support: A university perspective. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 9(2), 85-100. [ Links ]

Schreiber, B., Luescher, T. M., & Moja, T. (2021). Developing successful transition support for students in Africa: The role of academic advising. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 9(2), vi-xii. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. (2017). Poverty trends in South Africa: An examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. Statistics South Africa.

Terblanche, H., Mason, H., & van Wyk, B. (2021). Developing mind-sets: A qualitative study among first-year South African university students. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 9(2), 199-216. [ Links ]

Tiroyabone, G. W., & Strydom, F. (2021). The academic advising issue. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 9(2), xiii-xiv. [ Links ]

van Pletzen, E., Sithaldeen, R., Fontaine-Rainen, D., Bam, M., Shong, C. L., Charitar, D., Dlulani, S., Pettus, J., & Sebothoma, D. (2021). Conceptualisation and early implementation of an academic advising system at the University of Cape Town. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 9(2), 31-45. [ Links ]

van Zyl, A., Dampier, G., & Ngwenya, N. (2020). Effective institutional intervention where it makes the biggest difference to student success: The University of Johannesburg (UJ) integrated student success initiative (ISSI). Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 8(2), 59-71. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage.

Received 24 August 2022

Accepted 20 January 2023

Published 14 August 2023