Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa

versão On-line ISSN 2307-6267

versão impressa ISSN 2311-1771

JSAA vol.11 no.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v11i1.4586

SPECIAL ISSUE: RESEARCH ARTICLE

Developing student affairs as a profession in Africa

Angélique WildschutI; Thierry M. LuescherII

IHuman Sciences Research Council; University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: awildschut@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0003-0361-3702

IIHuman Sciences Research Council, Cape Town; Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, South Africa. Email: tluescher@hsrc.ac.za. ORCid: 0000-0002-6675-0512

ABSTRACT

This article discusses the nature of the professionalization of student affairs and services (SAS) in Africa by analysing the discourses evident and legitimated through the Journal of Student Affairs in Africa (JSAA). The analysis is driven by three research questions: (1) What is the extent of the journal's engagement with the terms 'profession', 'professionalism', 'professional', and 'professionalization'? (2) How are these focal concepts used in the journal and (3) how do these uses relate to the social justice imperative in SAS? Overall, the analysis shows that the professionalization discourse in JSAA draws strongly on notions that certain professional traits and high-level knowledge and skills must be possessed by SAS personnel for the field to be professionalized. Furthermore, the analysis reflects a stronger social justice discourse than a discourse on SAS as a profession. Finally, this article considers opportunities for a scholarship on the development of SAS as a profession.

Keywords: Higher education, professionalization, professionalism, social justice, sociology of professions, student affairs

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article aborde la nature de la professionnalisation des Œuvres Estudiantines (O.E.) dans les universités africaines en analysant les discours évidents et légitimés à travers le Journal of Student Affairs in Africa (JSAA). L'analyse s'articule autour de trois questions de recherche : Quelle est l'étendue de l'engagement de la revue avec les termes profession, professionnalisme, professionnel et professionnalisation ? Comment ces concepts centraux sont-ils utilisés dans la revue et comment ces utilisations sont-elles liées à l'impératif de justice sociale dans les O.E. ? Dans l'ensemble, l'analyse montre que le discours de professionnalisation dans le JSAA repose fortement sur l'idée selon laquelle certaines caractéristiques professionnelles, ainsi que certaines connaissances et compétences de haut niveau, doivent être maîtrisés par le personnel des O.E. pour que le domaine soit professionnalisé. En outre, l'analyse reflète un discours sur la justice sociale plus fort que sur les O.E. en tant que profession. Enfin, cet article envisage les possibilités d'une recherche sur le développement des O.E. en tant que profession.

Mots-clés: Enseignement supérieur, œuvres estudiantines, professionnalisation, professionnalisme, justice sociale, services étudiants, sociologie des professions

Introduction: The role of JSAA in professionalizing student affairs in Africa

The Journal of Student Affairs in Africa (JSAA) was established in 2012/13 with a launch issue themed 'The professionalization of student affairs in Africa' published in December 2013. The journal boldly states that it "aims to contribute to the professionalization of student affairs in African higher education" (JSAA, 2022). In the launch issue, the editorial executive claimed a "growing interest in the professionalization of student affairs in Africa". They noted recent developments in Africa, including a shift from "on-the-job training" to "high-level skills requirements to enter the profession"; a growing number of graduate programmes focusing on HE studies and SAS; new and existing centres of research to develop a body of knowledge and expertise; a growing number of SAS professional associations; increasing numbers of SAS conferences to share professional reflection on best practice and practice-relevant research, and; a budding of publications on SAS from the continent (Luescher-Mamashela et al., 2013a, p. viii-ix). To support these developments, it was argued that "an independent, international scholarly journal", dealing with "the theory, policy and practice" of the profession, was required (Luescher-Mamashela et al., 2013b, p. 5). Indeed, from the outset, the founding editors declared that this publication would strive to be "the foremost academic journal dealing with the theory and practice of the student affairs domain in universities on the African continent" (JSAA, 2021).

To contribute to professionalization, establishing scholarly legitimacy is critical and the JSAA editors embarked on this inter alia by seeking to establish "a prestigious editorial executive and international editorial board", publish "high quality content", have "rigorous internal quality controls", and seek "accreditation, patronage, endorsement, and affiliation" (Luescher-Mamashela et al., 2013b, p. 14-15). For a South Africa-based journal, perhaps the most important indicator of such scholarly legitimacy was accreditation by the Academy of Sciences of South Africa, which certified it in 2017 as bona fide scholarly journal included in the South African list of research subsidy-earning journals. Over the years, the journal has been able to attract authors from across the South African and African university landscape and about 10% of contributors from outside the African continent. This is in a context where JSAA is the only specialized journal on SAS in Africa (alongside general higher education and education journals), and one among a dozen or so journals worldwide dedicated to SAS scholarship (most of which are in the global North) (Zavale & Schneijderberg, 2022). By June 2023, the journal had a citation count of over to 1,700 for 249 items captured on its Google Scholar profile. Over 100 articles had achieved at least three citations with the top three articles respectively having 119, 93 and 58 recorded citations on Google Scholar. Regarding those and other indicators, over the years JSAA has established itself as a respectable building block in the research landscape on SAS in Africa.

To discuss the nature of the student affairs professionalization project in Africa, this article critically analyses the discourses evident and implicitly legitimated in the publications of JSAA over its 10 years of existence (Vol. 1, 2013 to Vol. 10, 2022). We argue that journals are important platforms for analysing 'efforts to professionalize' as well as 'claims to professionalism' (Evetts, 2013), because they create a discourse around the concept of profession and professionalism by documenting specific collections of cases that illustrate and model ways for the field to professionalize. While there are many other activities and processes that contribute to the wider professionalization project1, we consider here particularly the role of JSAA, recognised as a scholarly journal in the SAS field.

To start our analysis, we reflect on foundational and conceptual debates in the literature on professions which recognise the importance of the ideological discourse on professions as (re)produced through certain activities and platforms. This is followed by a brief overview of the methodology. We then present our analyses of a sample of articles published in the journal. The first is a bird's-eye view on the extent of engagement with the focal concepts of 'profession', 'professionalism', 'professional', and 'professionalization', which is followed by an in-depth analysis of the discourse on SAS as profession evident in a sample of articles. We also reflect on the social justice aims of the SAS domain and show how these fare in the journal's professionalization discourse. We do so by interrogating the alignment between the professionalization discourse and social justice discourse evident in JSAA. We consider the latter critical for engagement, not least because South African professions have historically used race and gender to exclude Black South Africans (see, e.g. Wildschut, 2011; Walker, 2005; Webster, 2004; Marks, 1994). In the case of SAS, focusing on social justice is perhaps even more important given the declared developmental and social justice aims of the profession (Ludeman & Schreiber, 2020; Schreiber, 2014). Some of the core tenets driving SAS include access, equality, diversity, assessment of student needs, and social justice (Perez-Encinas et al., 2020; Long, 2014). In the final section, we consider opportunities for scholarship on SAS as a profession and how JSAA positions itself in relation to steering this scholarship.

Professions, professionalism and professionalization

The sociology of professions (SoP) was pioneered by writers such as Eliot Friedson and Magali Larson, Andrew Abott and more recently authors such as Julia Evetts and Mike Saks. Despite several collections or case studies of particular professions in particular countries, more comprehensive books on professions are rarely produced, most notable would be the Sociology of Professions by McDonald (1995) Professions and Power (2016) by Johnson and a Routledge Companion to the Professions and Professionalism by Dent et al. (2016). The SoP literature examines professions as a type of occupational group that is successful in wielding forms of privilege, power, and status across a range of societal institutions (notably in relation to the market and the state) over, or at certain points in, time. A profession is commonly understood to refer to an occupational group that performs autonomously, has a particular relationship with society, and its practitioners are governed by a relatively exclusive form of knowledge and a code of ethics. As a profession manages knowledge that other individuals need, there tends to be an asymmetric relationship between professionals and the users of their services. In traditional theories of professions, a strong connection exists amongst the professions, higher education, a scientific knowledge base, and a code of ethics. However, arguments on the complexities of practical and tacit knowledge have come to play a central role in contemporary discussions and engagement about professions. In this respect it is also important to highlight the contested nature of concepts such as profession, professionalism, and professionalization in the course of analysing and interpreting a journal's positioning to their theoretical development.

The SoP literature can be categorised into three stages of development which illustrates why certain areas of investigation became more salient over time and others discarded. The first stage of development, referred to as the traditional trait approach (or taxonomic approach), claimed that professions could be defined by cataloguing particular traits and attributes that are not held by other occupations (e.g. Pellegrino, 1983; Wilensky, 1964; Greenwood, 1957). Scientific knowledge and specialized expertise were seen as the defining features in these accounts. The literature was based on two core propositions, namely that professions were distinct from other middle-class occupations, both empirically and analytically, and that the presence of professions in civil society uniquely supported the social order. Saks (2012) noted in this respect that occupations with very esoteric and complex knowledge and expertise of great importance to society were usually seen as being granted a high position in the social system with state sanction in return for protecting the public and/or clients. The medical profession was often used to represent such a prototype.

The SoP theorists of this stage suggested a common professionalization process where relatively few occupations would complete all the steps in the process to achieve the standing of established profession.

The second phase in SoP scholarship, coined the revisionist triad, rejected the idea that professions could be distinguished from occupations. Writers did so by showing that rather than distinct differences existing between high-status professions and other occupations, there were many parallels. Often low status occupations (such as garbage collectors or prostitutes) were used to discredit claims that only a limited number of professions were worthy of such a title. Here arguments of the forces of de-professionalization also played a role. For example, Braverman (1974) argued that tasks that would be seen as the preserve of a particular profession were being broken down by managerialist strategies and could easily be performed by other groups, or they became subject to a division of labour that would circumvent the high status of professions. Furthermore, there was also a recognition that professions can be a malevolent force in society with detrimental consequences for order and stratification, exacerbating hierarchies and socio-economic inequities.

While agreeing with many of the critics of the second phase, Abbott (1988) was influential in arguing that the study of professions must recognise them as a system and focus on how occupational groups define, establish, and maintain boundaries or lay claim to certain jurisdictions. Abbott focused on the activities by which occupational groups asserted jurisdiction to the point that they would gain the right (by society, the market, and the state) to offer 'diagnosis, inference and treatment' on a specific scope of problems. As this view explicitly accommodates changes in the nature of work and new contestations between occupational groups trying to claim parts or entire scopes of practice, his seminal work continues to inform current research in the field (Wildschut & Meyer, 2017).

More recent literature on professions attempts to synthesize the tensions from the first two phases in recognising definitional integrity as important, but being wary of the functionalist implications (Sciulli, 2005). Here arguments are for moving beyond a professional framework (Burns, 2007), focusing more on the micro-level of professionals and their workplaces (Brock et al., 2014) as well as the discourse of professionalism. In this regard the literature further distinguished conceptually between professionalization from within and from without (McClelland, 1990) to signal that professionalism can be externally imposed (e.g. by regulatory authorities and standard setting bodies) as a means of control as well as internally enacted to assert autonomy and contest the power of bureaucracy (Fournier, 1999). It was considered important to delineate between professionalism that is driven by practitioners themselves striving towards and wanting to deliver a quality service, protect client rights and interests, from the forms of professionalism that are driven by requirements to adhere to quality standards, assurance and organisational targets. This led to the former being viewed as a more legitimate form of professionalism as opposed to the latter which was associated with professional organisations creating, institutionalising and manipulating the discourse of professionalism (Muzio & Kirkpatrick, 2011) to restrict professional autonomy and power. Recent scholarship, however, suggests that these are not necessarily dichotomous (Wilkesmann, 2020).

The scholarship now focuses on professionalism as a value and ideology and continues to debate whether the terms profession and professionalism are useful and theoretically relevant (Adams, 2010; Saks, 2012; Svarc, 2016). This is a debate returned to, most recently in Sak's book, Professions: A Key Idea for Business and Society (2021, p. vii), where he asserts the "ongoing importance of professional groups in the modern world in business and beyond". Thus, the terms 'profession', 'professionalism' and 'professionalization' are contested, depending critically on socio-economic and historical development within a specific context. This means that no 'template' or model for successful professionalization can easily be distilled. These terms must be applied in a manner that engages the conceptual gaps, and continuous critique of the nature of professionalization is required to ensure that social and structural exclusions are not recreated or maintained.

Research questions and methodology

Understanding professions requires understanding, first, the role certain actors play in the professionalization processes and, second, the way they may influence new forms of professionalism and models of professionalization (Muzio & Kirkpatrick, 2011). This article investigates the way the Journal of Student Affairs in Africa has contributed over the first ten years of its existence to the professionalization of SAS in Africa.

Three research questions guide the enquiry: (1) What is the extent of the journal's engagement with the focus terms of 'profession', 'professionalism', 'professional', and 'professionalization'? (2) How are these terms applied in publications in the journal? (3) To what extent does this professionalization discourse relate to the social justice imperative in SAS?

The data for this study are the 10 volumes of JSAA published from 2013 to 2022, which comprise 19 issues and 240 substantive items of publication. Our analysis started by importing the items of publication (including prefaces, editorials, peer-reviewed research articles, peer-reviewed reflective practice articles, campus and conference reports, professional notices and book reviews), into Atlas.ti 9 to run a comprehensive content analysis of the selected focus terms. Atlas.ti offers the advantage of organising, managing, and analysing large quantities of qualitative data.

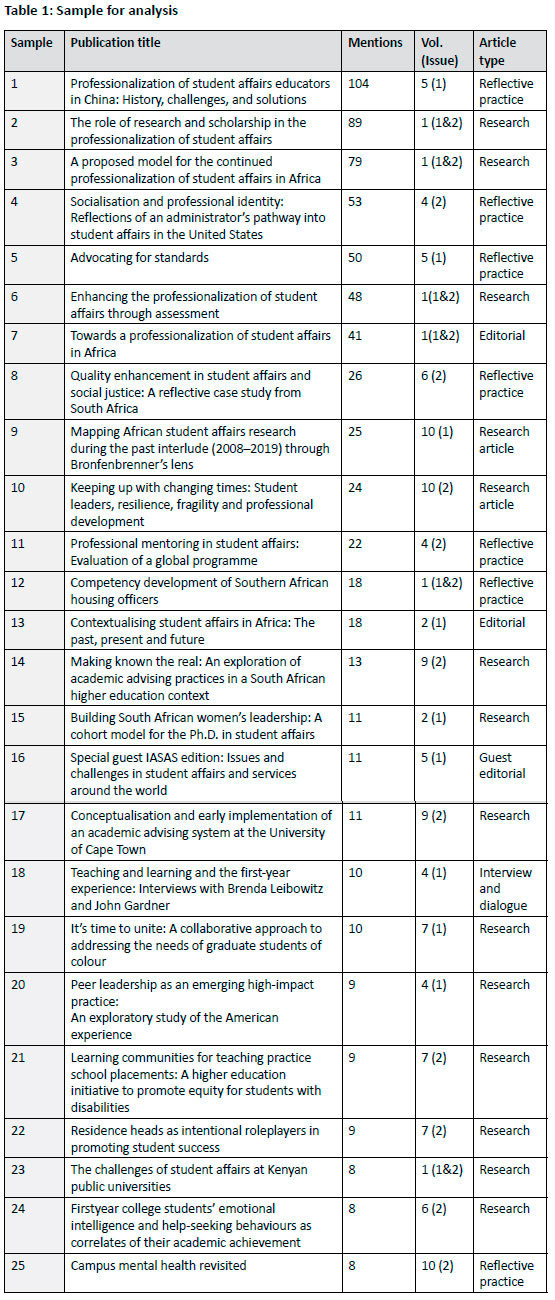

Our analytic process employed both a deductive and inductive approach to the development and application of codes and themes to condense the selected data. Using Atlas.ti's automated search function, 131 published items were identified that contain our focus terms (i.e. professionalism, profession, professional or professionalization). Of these, 25 publications were selected as the sample for our in-depth analysis by excluding all documents in which these terms were mentioned less than eight times (see Table 1 below). This constitutes the database for the discourse analysis.

Discourse analysis aims to uncover discursive, interactional, and/or rhetorical context (Macmillan, 2005), making explicit the unspoken, lived notions surrounding power (Foucault, 1976) through a "set of methods and theories for investigating language in use and language in social contexts" (Wetherell et al., 2001, p.1). Our focus here is analysing discourse as realised through text, while acknowledging that it is also about objects, subjects, and meaning-making, in reference to other discourses, reflective of a particular way of speaking, and historically located (Parker, 1992).

Our method was to read each contribution closely, paying attention to the deployment of our focus terms to identify what meaning could be discerned from their contextual usage and thus what discourse it established or participated in. We then reflected on whether and how these meanings related to the discourse on professions, as discussed above.

Constructing the discourse of SAS as a profession

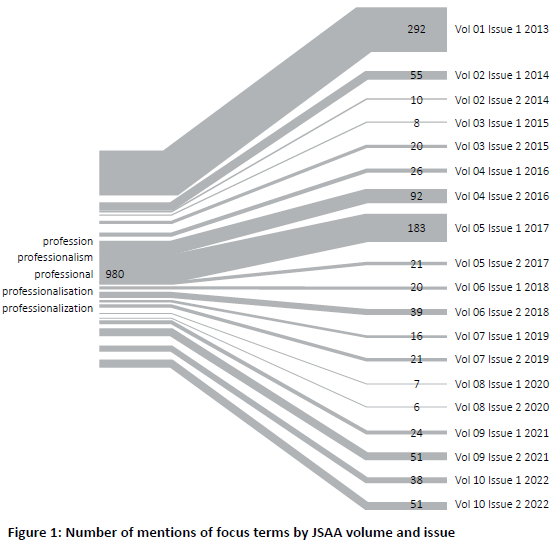

The analysis of all 240 substantive items of publication provides a bird's-eye view of the engagement of JSAA in the SAS professionalization discourse. Figure 1 shows that there have been great disparities in the distribution of mentions (over 980) of the term 'profession' and its derivatives between the different volumes and issues of the journal since its inception in 2013. It shows that the JSAA launch issue themed 'The professionalization of student affairs in Africa' accounts for almost a third of all mentions of the search words. This is followed by JSAA's global issue of 2017, 'Voices from across the globe', which contains 183 mentions, and the 2016 volume on 'Student affairs in complex contexts' (92 mentions). While almost half (7 of 16) of the issues have been guest-edited, only one of the five issues with the most mentions are guest-edited. This suggests that those issues edited by the editorial executive of the journal are more actively engaged in the construction of the SAS professionalization discourse than guest-edited issues. The diagram also highlights an ebb and flow in focus on professionalization across issues.

Deconstructing the SAS professionalization discourse

On the basis of the above analysis, we identified the 25 articles with the most mentions of the focal terms (eight or more mentions) as the sample for our in-depth discourse analysis. This sample is made up of fourteen research articles, seven reflective practice articles, three editorials, and one interview and dialogue article (see Table 1).

First, we considered whether a document attempted to foster a particular perspective and meaning of SAS as profession and SAS professionalization. Does it try to frame an understanding in a particular manner? Second, we considered whether new conceptualisations were proposed that can contribute to the development of the discourse on SAS as a profession or beyond.

Among the 25 contributions, six explicitly deal with the conceptualisation of one or more of our focus concepts; ten do not explicitly deal with conceptualisations of the terms but their content portrays a perspective on what these concepts must mean for SAS; and the remaining nine do not engage with the concepts at all but merely deploy the terms uncritically.

Among the first set of six articles, which explicitly define their profession-related concepts, is the article by Li and Fang published in JSAA 5(1) of 2017. It is entitled 'Professionalization of student affairs educators in China: History, challenges, and solutions' and directly engages with the concept of professionalization. The article frames an intervention from central university administrations and the Chinese government as important for the initial success of the professionalization of SAS in China.

Next, the article 'The role of research and scholarship in the professionalization of student affairs' by Carpenter and Haber-Curran published in the 2013 launch issue directly conceptualises what it means to be a professional and what professionalization entails. It discusses scholarly practice, the meaning of being a practitioner-scholar, and therefore the concept of professionalism, emphasizing the importance of professionally conducted, written, and vetted research and scholarship as the most essential components of professional development. They conceptualise scholarly practitioners as those who

practice their craft as autonomously as possible by making decisions primarily for the benefit of students, relying upon theory and research, remaining accountable to peers, providing professional feedback, acting ethically, and enacting the values of the profession generally. (Carpenter & Haber-Curran, 2013, p. 8)

In the same issue, Selznick also engages with the concepts of professionalization and professionalism in his article 'A proposed model for the continued professionalization of student affairs in Africa'. Selznick argues that a model of professionalization ought to be sensitive to the three core dimensions of SAS work (i.e. entering services, supporting services, and culminating services), as well as adaptable to the variety of contexts found within African higher education, to guide the development of the profession.

Pansiri and Sinkamba (2017, Vol. 5 Issue 1) argue for a professional approach to SAS that places emphasis on standards. Their article, 'Advocating for standards in student affairs departments in African institutions: University of Botswana experience', argues that professions must have set standards that guide their work. Furthermore, they assert that professional bodies with established, tried, and tested standards are critical to professional development in the field. This is an important contribution as it is only one of two articles in this set by authors that work in African higher education.

Another article from the launch issue entitled 'Enhancing the professionalization of student affairs through assessment' by Gansemer-Topf puts emphasis on the role of assessment in legitimating SAS as profession. It defines both 'profession' and 'professional' to argue that there are certain characteristics that provide insights into SAS evolution from a mere practice to a profession. This aligns to earlier discussion of an evolutionary view of professionalization from one end of the spectrum of occupational practice to the other side, which is a professionalized state.

The sixth article of the set that explicitly dealt with defining our focus concepts was published in the first issue of 2022 with the title 'Mapping African student affairs research during the past interlude (2008-2019) through Bronfenbrenner's lens'. The authors, Holtzhausen and Wahl, both work in a South African university. Their article critiques the traditional notions of professionalism as elitist, paternalistic, and authoritarian, associated with highly exclusive knowledge, control and detachment. Using humanizing and transformative pedagogy as a framework, they argue for a more collaborative and democratic view of professional work that allows acknowledgement of the professionalism required in, for instance, student leadership-related work. The article illustrates how SAS practitioners are required to mediate the university's organizational goals in relation to student needs alongside an acknowledgement that university staff and student leaders must embrace their own and each other's full humanity and develop as semi-professionals and peer-educators.

Among the sample of 25 that do not attempt to explicitly conceptualise the focal concepts, there are still articles that make claims on what their authors deem to be professional practice. Prominent are discussions of skills and competencies associated with SAS as profession, considerations of processes or structures that contribute to professionalization, delineation of responsibilities in respect to other fields of practice, as well as arguments that highlight the boundary straddling position of the field and its practitioners. In other words, they establish and elaborate on a taxonomy of traits to define SAS as profession, SAS professionalism and the processes of professionalization required to get there.

In the main, we therefore find in the articles a tendency towards rather uncritical notions of what a profession is and what the professionalization of SAS entails in Africa. Critical engagement with the established scholarly discourses on professions that underpin these key constructs is nearly absent. In the instances where literature on professions is reviewed and drawn on, the 25 JSAA articles apply for the most part approaches that tend to be rejected by mainstream SoP literature. A case in point is the widespread use of the so-called taxonomic approach, which basically establishes catalogues of traits and attributes that a particular profession ought to espouse. While there is heuristic advantage in such applications, it would be important for a journal that is committed to the development of the professionalization discourse to engage with the way this uncritical approach positions SAS scholarship on the professionalization of student affairs and the professionalism of its practitioners.

High-level skills and knowledge as well as social justice

The ongoing, rapid massification of higher education in Africa has led to a diversification of university's student and staff bodies along with many challenges for student affairs in Africa (Luescher, 2020). SAS is challenged to ensure that widening participation and diversity does not exacerbate existing inequalities and/or generate new ones but ensure "equity and inclusion initiatives to address and redress longstanding practices of exclusion and privilege (typically along race, ethnicity, sex, gender and socio-economic class lines)" (Blessinger et al., 2020, p. 85; Ludeman & Schreiber, 2020). A SAS profession that does not explicitly acknowledge and involve a social justice mandate would be amiss. Our last concern is therefore a critical analysis of the already identified discourse on SAS as a profession in the JSAA in relation to social justice concerns.

This analysis required two additional rounds of coding. The first identified terms associated with the concepts of high-level skill and knowledge which, as established earlier, are historically considered important aspects of a profession. The related search terms and codes were: 'formal training', 'formal education', 'high-skills', 'university qualification', 'student development knowledge', 'student development theory', 'student learning theory', 'advising theory', 'specialized knowledge', and 'professional qualification'. The second set of search terms associated loosely with social justice concerns included 'social justice', 'disadvantage', 'poor', 'inequality', 'equality', 'marginalized', 'access', 'race', 'black', 'coloured', 'female', 'disability', and 'exclusion'. The face validity of these terms was tested through discussion and adjustment between the authors.

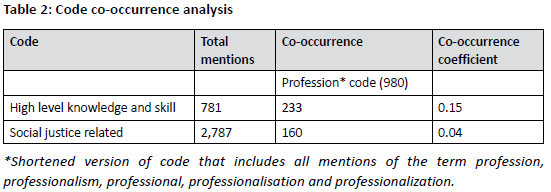

The first column of Table 2 gives an indication of the occurrence of the two codes generated by the search. Over the journal life cycle there were a total 2,787 mentions of terms related to social justice. For the notions of high-level skills and knowledge, a much smaller number of mentions (781) leads us to assert that, comparatively, the social justice imperative forms a much larger driver of the general SAS discourse in the contexts of the journal articles. The analysis illustrates well-developed engagement with terms that relate to social justice.

When we consider code co-occurrence in a cross-tabulation of codes that co-occur in the same paragraph, it appears that the discourse of SAS as profession more actively engages the notions of high-level skills and knowledge (233) in support of its claims than those of social justice (160) (see Table 2, column 2). The code co-occurrence coefficient reflects the strength of the relation between two codes.2 In this regard the relation between the professions-related code is stronger with the high-level knowledge and skill code (0.15) than it is with the social justice related code (0.04) (see Table 2, column 3). This means that the professionalization discourse is much more strongly associated with (relatively uncritical and traditional) notions of high-level knowledge and skills than it is with (critical and engaged) notions of social justice.

A similar insight is also illustrated when considering co-occurrence against the total number of extracts in the particular code: 29.8% of all high-level knowledge and skills codes co-occurred with coding related to SAS as profession, compared to only 5.7% of social justice-related codes. Further analysis shows that discussions in the journal of social justice mostly related to students and less to SAS as profession. Against this finding, it may be useful to consider whether and how the journal would like to position its professionalization agenda in relation to the social justice imperative involved in SAS work, given its powerful role in developing the discourse on SAS as profession in Africa and beyond (e.g. Schreiber, 2014).

Conclusions and way forward

We have shown that in keeping with its establishment rationale, JSAA is developing a discourse on SAS as a profession in Africa which could benefit from more critical engagement. First, our analysis illustrates that the dominant discourse on SAS as profession evident in a sample of JSAA publications builds on rather traditional (and in parts outdated) notions of what a profession is, typically involving catalogues of traits and attributes that a particular profession ought to espouse. Our analysis showed that the discourse on SAS as profession is dominated by notions of high-level knowledge, skills and quality standards (and ways towards building those).

Second (and related to this), the professionalization discourse in JSAA would benefit from more critical engagement with respect to the potential effect of particular routes to professionalization of SAS in Africa on equity, diversity, inclusion, and social justice. What will the effect of professionalization be on gender equity, the inclusion of members of historically disadvantaged communities, persons with disabilities, and so forth? As much as there is a well-established social justice discourse in the journal, its intersection with the discourse of SAS as profession is minimal.

Third, we found the wider professionalization discourse in JSAA strongly aligns with the notion of service to students and being governed by professional values internal to practitioners themselves. As indicated earlier, this is sometimes referred to in the literature as professionalization from within (Fournier, 1999). Two examples in our sample of JSSA articles that reflect this are Carpenter and Haber-Curran (2013) and Selznick (2013). There are also several articles that provide evidence of managerialist influences on SAS, such as external standard setting and quality assurance that are illustrative of professionalization from outside (Wilkesmann et al., 2020). This is exemplified by Li and Fang (2017), Pansiri and Sinkamba (2017), and Luescher (2018) in their articles referred to above.

Linking to the earlier discussion, this finding is of relevance to further analytical and conceptual development that can be illustrative of how newer and emerging professions are navigating both forms of professionalism in their efforts to professionalize. This could add further nuance to our understanding of how such forms of professionalism are not always diametrically opposed. Reflection on how the tension between professionalism from within and outside plays out within SAS, and particularly its form within the African context, could thus be instructive to this debate.

Lastly, and related to the former assertion, there is an interesting development in the JSAA discourse on professionalization. In the last volume reviewed here, there are two articles, Holtzhausen and Wahl (2022) and Dick et al. (2022) respectively, that recognise a semi-professional role played by student leaders in SAS. Student leaders are often taken as extensions of SAS practitioners in student leadership development, the residence sector, mentoring practice, and so forth. This raises the question of the unique nature of SAS as profession in the African higher education context and highlights the role that JSAA can play through providing a critical platform for engaging on the nature of SAS professionalization in Africa. The growing collection of scholarship on SAS as profession in JSAA therefore has immense practical and theoretical potential.

Acknowledgements

This article follows from an earlier version that was prepared for the series New Directions in Student Services. The present version has been significantly updated with the latest data and with additional qualitative data and analysis. All sections have been revised and refocused to the 10-year anniversary issue of the Journal of Student Affairs in Africa.

Ethics statement

This desktop study of secondary, published data did not involve research with human subjects and was not submitted for ethics review.

Potential conflict of interest

Apart from their own involvement as editors of the Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, the authors do not consider any potential conflicts of interest. Both authors conducted this work as researchers employed by the Human Sciences Research Council and research associates of the University of Pretoria and Nelson Mandela University, respectively.

Funding acknowledgement

No funding was received specifically for this work.

References

Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press.

Adams, T. (2010). Profession: A useful concept for sociological analysis? Canadian Review of Sociology, 47(1), 49-70. DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-618X.2010.01222.x. [ Links ]

Blessinger, P., Hoffman, J., & Makhanya, M. (2020). Towards a more equal, inclusive higher education. In R. B. Ludeman & B. Schreiber et al. (Eds.), Student affairs and services in higher education: Global foundations, issues, and best practices (3rd ed) (pp. 85-87). International Association of Student Affairs and Services (IASAS) in cooperation with the Deutsches Studentenwerk (DSW). http://iasas.global/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IASAS_Student-Affairs-in-Higher-Ed-2020.-FINAL_web.pdf

Braverman, H. (1974). Labour and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century. Monthly Review Press. https://caringlabor.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/8755-labor_and_monopoly_capitalism.pdf

Brock, D. M., Leblebici, H., & Muzio, D. (2014). Understanding professionals and their workplaces: The mission of the Journal of Professions and Organisation, Journal of Professions and Organization, 1(1), 1-15. DOI: 10.1093/jpo/jot006. [ Links ]

Burns, E. (2007). Positioning a post-professional approach to studying professions. New Zealand Sociology, 22(1), 69-98. [ Links ]

Carpenter, S., & Haber-Curran, P. (2013). The role of research and scholarship in the professionalization of student affairs. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 1(1&2), 1-9. DOI: 10.14426/jsaa.v1i1-2.20. [ Links ]

Dick, L., Müller, M., & Malefane, P. (2022). Keeping up with changing times: Student leaders, resilience, fragility and professional development. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 10(2), 61-77. DOI: 10.24085/jsaa.v10i2.2554. [ Links ]

Eskell Blokland, L., & Kirkcaldy, H. (2022). Campus mental health revisited. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 10(2), 195-207. DOI: 10.24085/jsaa.v10i2.4368. [ Links ]

Evetts, J. (2003). The sociological analysis of professionalism occupational change in the modern world. International Sociology, 18(2), 395-415. DOI: 10.1177/0268580903018002005 [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1976). The history of sexuality: Volume I, an introduction. Penguin Books.

Fournier, V. (1999). The appeal to 'professionalism' as a disciplinary mechanism. Social Review, 47(2), 280-307. DOI: 10.1111/1467-954X.00173. [ Links ]

Fournier, V. (2000). Boundary work and the (un-) making of the professions. In N. Malin (Ed.), Professionalism, boundaries and the workplace (pp. 67-86). Routledge.

Gansemer-Topf, A. M. (2013). Enhancing the professionalization of student affairs through assessment. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 1(1&2), 23-32. DOI: 10.14426/jsaa.v1i1-2.33. [ Links ]

Google Scholar. (2022). Profile: Journal of Student Affairs in Africa. Cited by: All. March 30, 2022. [Unpublished].

Greenwood, E. (1957). Attributes of a profession. Social Work, 2(3), 45-55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23707630 [ Links ]

Holtzhausen, S. M., & Wahl, W. P. (2022). Mapping African student affairs research during the past interlude (2008-2019) through Bronfenbrenner's lens. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 10(1), 1-14. DOI: 10.24085/jsaa.v10i1.2524. [ Links ]

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa (JSAA). (2022). About the Journal. https://upjournals.up.ac.za/index.php/jsaa

Li, Y., & Fang, Y. (2017). Professionalisation of student affairs educators in China: History, challenges, and solutions. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 5(1), 41-50. DOI: 10.24085/jsaa.v5i1.2481. [ Links ]

Long, D. (2012). The foundations of student affairs: A guide to the profession. In L. J. Hinchliffe & M. A. Wong (Eds.), Environments for student growth and development: Librarians and student affairs in collaboration (pp. 1-39). Association of College & Research Libraries.

Ludeman, R. B., & Schreiber, B., et al. (Eds.). (2020). Student affairs and services in higher education: Global foundations, issues, and best practices (3rd ed.). International Association of Student Affairs and Services (IASAS) in cooperation with the Deutsches Studentenwerk (DSW).

Luescher, T. M. (2018). Quality enhancement in student affairs and social justice: A reflective case study from South Africa. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 6(2), 65-83. DOI: 10.24085/Jsaa.v6i2.3310. [ Links ]

Luescher, T. M. (2020). Higher education expansion in Africa and Middle East. In P. N. Teixeira & J. C. Shin (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of higher education systems and institutions (pp. 655-658). Springer.

Luescher-Mamashela, T. M., Moja, T., & Schreiber, B. (2013a). Towards the professionalization of student affairs in Africa? Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 1(1&2), vii-xiii. DOI: 10.14426/jsaa.v1i1-2.18. [ Links ]

Luescher-Mamashela, T. M., Overmeyer, T., & Schreiber, B. (2013b). Draft business plan for the development, launch and first five years of the new Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 2012 -2018. [unpublished].

Macmillan, K. (2005). More than just coding? Evaluating CAQDAS in discourse analysis of news texts. Forum: Qualitative social research, 6(3), 25. DOI: 10.17169/fqs-6.3.28. [ Links ]

McClelland, C. E. (1990). Escape from freedom? Reflections on German professionalization 1870-1933. In R. Torstendahl & M. Burrage (Eds.), The formation of professions: Knowledge, state and stra tegy (pp. 97-113). Sage.

Muzio, D., & Kirkpatrick, I. (2011). Introduction: Professions and organisations - a conceptual framework. Current Sociology, 59(4), 389-405. DOI: 10.1177/0011392111402584. [ Links ]

Pansiri, B. M., & Sinkamba, R. P. (2017). Advocating for standards in student affairs departments in African institutions: University of Botswana experience. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 5(1), 51-62. DOI: 10.24085/jsaa.v5i1.2482. [ Links ]

Parker, I. (1992). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology. Sage.

Pellegrino, E. D. (1983). What is a profession? Journal of Allied Health, 12(3), 168-176. [ Links ]

Perez-Encinas, A., Pillay, S., Skaggs, J. A., & Strange, C. C. (2020, August 17). Principles, values and beliefs of student affairs and services. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200817155607351

Saks, M. (2012). Defining a profession: The role of knowledge and expertise. Professions & Professionalism, 2(1), 1-10. DOI: 10.7577/pp.v2i1.151. [ Links ]

Saks, M. (2021). Professions: A key idea for business and society (1st edn). Routledge.

Schreiber, B. (2014). The role of student affairs in promoting social justice in South Africa. Journal of College and Character, 15(4), 211-218. DOI: 10.1515/jcc-2014-0026 [ Links ]

Sciulli, D. (2005). Continental sociology of professions today: Conceptual contributions. Current Sociology, 53(6), 915-942. DOI: 10.1177/0011392105057155. [ Links ]

Selznick, B. (2013). A proposed model for the continued professionalisation of student affairs in Africa. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 1(1&2), 11-22. DOI: 10.14426/jsaa.v1i1-2.35. [ Links ]

Svarc, J. (2016). The knowledge worker is dead: What about professions? Current Sociology, 64(3), 392-410. DOI: 10.1177/0011392115591611. [ Links ]

Walker, L. (2005). The colour white: Racial and gendered closure in the South African medical profession. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(2), 348-375. DOI: 10.1080/01419870420000315889. [ Links ]

Webster, E. (2004). Sociology in South Africa: Its past, present and future. Society in Transition, 35(1), 27-41. DOI: 10.1080/21528586.2004.10419105. [ Links ]

Wetherell, M., Taylor, S. J. A., & Yates, S. J. (Eds). (2001). Discourse as data: A guide for analysis. Sage.

Wildschut, A., & Gouws, A. (2013). Male(volent) medicine: Tensions and contradictions in the gendered re/construction of the medical profession in South Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 44(2), 36-53. DOI: 10.1080/21528586.2013.802536. [ Links ]

Wildschut, A., & Meyer, T. (2017). The boundaries of artisanal work and occupations in South Africa, and their relation to inequality. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 27(2), 113-130. DOI: 10.1080/10301763.2017.1346450. [ Links ]

Wilensky, H. (1964). The professionalisation of everyone? American Journal of Sociology, 70(2), 137-158. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2775206. [ Links ]

Wilkesmann, M., Ruiner, C., Apitzsch, B., & Salloch, S. (2020). 'I want to break free' - German locum physicians between managerialism and professionalism. Professions & Professionalism, 10(1), e3124. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7111-7554 [ Links ]

Zavale, N. C., & Schneijderberg, C. (2022). Mapping the field of research on African higher education: A review of 6483 publications from 1980 to 2019. Higher Education, 83, 199-233. DOI: 10.1007/s10734-020-00649-5. [ Links ]

Received 11 May 2023

Accepted 23 June 2023

Published 14 August 2023

1 Professionalization can include the development of professional and academic degrees at undergraduate and postgraduate level, short courses and capacity building opportunities, scholarship and research and the expansion of discipline-specific journals and books, the building of epistemic communities and developing theories and practices that are globally shared and locally relevant (Schreiber & Lewis, 2020).

2 The calculation of the code co-occurrence co-efficient is c=n12/(n1+n2-n12), where n12 = number of co-occurrences for code nl and n2. It ranges from 0 - 0, where 0 would be no co-occurrence of codes and 1 would mean that the two codes co-occur wherever they are used.