Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

versión On-line ISSN 2305-8862

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2329

SAJOG vol.28 no.1 Cape Town jun. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJOG.2022.v28i1.2087

RESEARCH

Maternal experiences of care following a stillbirth at Steve Biko Academic Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

A S JimohI; J E WolvaardtII; S AdamIII

IMB ChB; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIPhD; School of Health Systems and Public Health, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIIPhD; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Despite improvements in obstetrics and neonatal care, the stillbirth rate remains high (23 per 1 000 births) in South Africa (SA). The occurrence of a stillbirth is a dramatic and often life-changing event for the family involved. The potential consequences include adverse effects on the health of the mother, strain on the relationship of the parents, and strain on the relationship between the parents and their other children. The standard of care in SA follows the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Green-top guidelines

OBJECTIVES: To explore maternal experiences of in-patient care received in cases of stillbirth

METHODS: A descriptive phenomenological approach was performed in the obstetrics unit at Steve Biko Academic Hospital, Pretoria, SA. Post-discharge interviews were conducted with women who experienced a stillbirth. The healthcare workers in the obstetric unit were also interviewed on the care provided to these patients. Data analysis was performed using the Colaizzi's method

RESULTS: Data from the interviews with the 30 patients resulted in five themes relating to the maternal experience of stillbirth: 'broken heart', 'helping hand, 'searching brain, 'soul of service' and 'fractured system'. Healthcare worker participants emphasised the importance of medical care (the clinical guidelines) rather than maternal care (the psychosocial guidelines

CONCLUSION: While the medical aspects of the guidelines are adhered to, the psychosocial aspects are not. Consequently, the guidelines require adaptation, especially taking into consideration African cultural practices, and the inclusion of allocated responsibility regarding the application of the psychosocial guidelines, as this is the humanitarian umbilical cord between healthcare workers and those in their care

Stillbirth is defined as a baby delivered with no signs of life after 24 completed weeks of pregnancy.[1] In South Africa (SA), stillbirths are defined as babies born with a body weight >500 g with no signs of life.[2] Stillbirth is a common occurence, with 1 in 200 babies stillborn in the UK (5 per 1 000 births).[3] In SA, the stillbirth rate is substantially higher with 32 178 stillbirths identified by the Perinatal Problem Identification Program (PPIP) at 588 sites in SA over a 2-year period (23 per 1 000 births).[4] The stillbirth rate in SA is regarded as unacceptably high by obstetric experts.

The causes of stillbirth include intrapartum complications, post-term pregnancy, maternal infections during pregnancy including malaria, syphilis and HIV, maternal disorders such as hypertension, obesity and diabetes mellitus, fetal growth restriction (FGR) and congenital abnormalities.[5]

At present, there is no SA-recommended guideline on the management of women with stillbirths. As a result, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Green-top guideline is generally used.[1] However, while these guidelines are accepted as the standard of care, the adherence to these guidelines in managing the traumatic experiences of women who deliver a stillborn baby is unknown. Follow-up appointments for counselling, discussion of test results and the possible cause of the stillbirth are not always scheduled.[4] As a result, a clear management plan for future pregnancies may be lacking. Data on whether the parents are offered or encouraged to take photographs of the baby or keep mementos, are lacking.

The RCOG Green-top guidelines suggest that the international standard of care in management of women who had stillbirths should involve counselling, investigations for possible causes of stillbirth and follow-up visits to review results and discuss future pregnancies.[1] Counselling is offered to bereaved parents and their family members as there is an increased risk of prolonged severe psychological reactions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and postnatal depression in the mother.[6] The investigation for the possible cause of the stillbirth should involve clinical assessment and laboratory tests. The underlying cause may impact on the risk of recurrence and the possibility of interventions in further pregnancies.[1] In addition, parents should be advised that in almost half of stillbirths, no specific cause is found.[11 The follow-up visit should include advice about the cause of stillbirth and any specific means of preventing a future loss. At the same visit, women should also be offered prenatal advice about modifiable factors - for example, support for smoking cessation and how to avoid weight gain if they are already overweight.[1] The follow-up visit is also recommended by Robson et al.,[7] who state that some risk factors for stillbirth are modifiable (and therefore warrant informing the women during a follow-up visit) while some are non-modifiable. The non-modifiable factors include low socioeconomic status and increased maternal age. On the other hand the modifiable risk factors such as obesity and smoking could be addressed before the next pregnancy.[8] Women should also be counselled on the advantages of delaying conception until any psychological issues have been resolved.[1]

The current standard of care in SA follows the RCOG Green-top guidelines as outlined by the National Department of Health in the maternity care guidelines of SA.[2] These guidelines encourage healthcare workers to be consistently sympathetic and supportive to mothers who experience stillbirths. Mothers or parents are encouraged to hold and spend time with the baby. Adequate counselling that is sensitive to the normal grief responses and includes an explanation of the cause of fetal death (if known) to the mother/parents is mandatory.[2]

Perinatal loss is known to be associated with short-term and long-term consequences for mental health and wellbeing, for example, depression, anxiety, PTSD and relationship difficulties[9] There is a 40% higher risk of a parental relationship dissolving after a stillbirth, when compared with a live birth.[10] Other family members including existing children and grandparents can also be adversly affected and should be included in counselling.[1] A study by Mills et al.[11] revealed that parents' experiences of pregnancy are profoundly altered by a previous perinatal death. They may experience conflicted emotions, extreme anxiety and lack of faith in a good outcome. Emotional and psychological support have been shown to improve these feelings. These findings are supported by another study which showed that, following a stillbirth, parents disclosed how the prospect of a subsequent pregnancy was fraught with fears about the potential loss of another baby.[12] Support after perinatal loss can improve the state of mental health of bereaved couples and that of their families.[13]

Despite stillbirths being common in SA, very few local studies have been conducted to investigate the experiences of women who have delivered stillborn babies, and their satisfaction with the care that they receive. It is vital to explore these women's experiences to help healthcare workers offer holistic and optimal care to patients.

The aims of this study were to explore the experiences of women and their views on the care they received.

Methods

A phenomenological study was conducted at the obstetrics unit at Steve Biko Academic Hospital (SBAH) in Pretoria, SA. The obstetrics unit is a referral unit that cares for pregnant women with maternal or fetal complications. It is part of the national PPIP database for auditing perinatal deaths. A phenomenological study is described by Giorgi[14] as a research study design that uses qualitative methods to explore and describe how human beings experience a certain phenomenon.

All women who had delivered stillborn babies at SBAH during the period December 2019 - February 2020 were invited to participate in the study. Women <18 years of age were excluded due to the additional requirement of obtaining permission from a guardian older than 18 years of age. Purposive sampling was used. Purposive sampling, also called judgement sampling, is the deliberate choice of a participant due to the qualities the participant possesses.[15] It is a non-random technique that does not need underlying theories or a set number of participants. Sampling continued until saturation was reached i.e., no new ideas/concepts emerged in the data analysis. The women were interviewed after discharge to prevent any perceptions that their opinions affected the care that they received.

Data on the demographic characteristics, pregnancy history and antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care of the participants were collected via a semi-structured, in-depth interview using an interview guide. The interview guide was developed based on the recommendations of the RCOG Green-top guideline.[1] The participants were encouraged to express their views and experiences in an open-ended manner. Interviews lasted between 45 and 60 minutes, were audio-recorded and took place in a private and safe environment after discharge, within the obstetrics unit at SBAH. The principal investigator (PI) conducted all the interviews in English. In addition, the participant's mental state and risk for postnatal depression was screened with the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS).[16] All participants who showed or reported distress during the interview were referred to a psychologist. Clinical information was extracted from patient records.

The healthcare workers i.e., midwives, social workers and doctors (obstetrics and gynaecology registrars and consultants) in the unit at the time of the study were individually invited to an interview on their opinion on the standard of care provided to these patients. Interviews were held at the end of rotation to avoid concerns of victimisation should their opinions be negative. Both day and night duty staff were invited to participate in the study.

The credibility of the data was ensured by collecting data from three different sources (triangulation), i.e. patients, healthcare workers and psychosocial support staff (social workers). Data collection was conducted over a 3-month period (prolonged engagement). Iterative data collection, i.e. analysing data continually informed future interviews (dependability). The research process and findings were discussed with peers (confirmability) and the PI maintained a reflective journal and audit trail (confirmability). A detailed description of findings and comparison to the existing literature make the findings transferable.

Data were professionally transcribed from the audio recordings. The text was cross checked by a second investigator. Qualitative data obtained from open-ended questions were coded manually. Colaizzi's method was used to analyse the data. The process entailed seven steps: transcribing the data in detail, excerpting the significant statements, concluding and extracting meaning, finding the characteristics and forming themes, developing the intact description, stating the essential structure of the phenomenon, and proving the truth of the content.[17] Codes were grouped into categories and emerging themes were described.

Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Pretoria's Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. 658/2019). Participants' autonomy was respected by obtaining written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study. Participants could withdraw consent at any time. Both individual and group interviews were conducted in a safe and private venue. All participants who were patients, were offered referral to a psychologist. Participants are identified by pseudonyms in this report.

Results

Patient participant perspectives

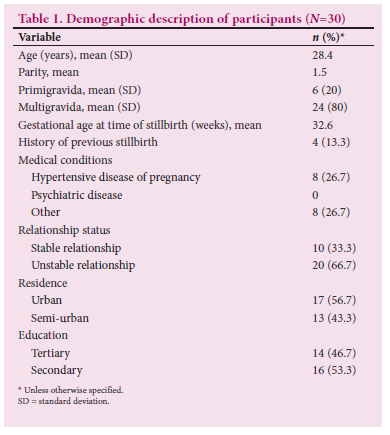

A total of 30 women participated in the study. Recruitment was stopped at this number as data saturation was achieved. The mean age of the participants was 28.4 years and the mean gestational age at the time of diagnosis of stillbirth was 32.6 weeks. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the participants.

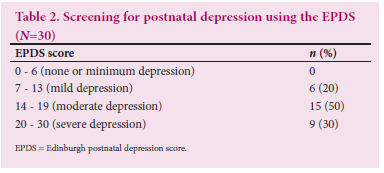

All participants were screened for postnatal depression using the EPDS. The results are summarised in Table 2.

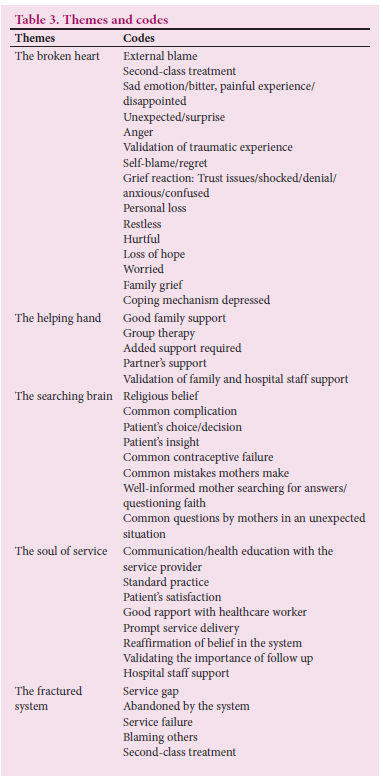

Five themes emerged from the women's experience of having a stillbirth (Table 3).

The broken heart

Participants were heartbroken after the stillbirth. They described the experiences as painful and unexpected; self-blame, external blame and loss of hope were common reactions - 'seeing the baby after delivery made me feel the pain' (Emma). Even though many of the participants knew the babies were dead in utero, it became a reality upon delivery, and seeing the babies made them very sad and confused.

The helping hand

The effect of support to women who experience stillbirth cannot be over-emphasised, as was apparent from the participants' narratives. Family and partner support were among the factors that participants said helped them through this difficult time: 'I have my supportive family' (Joyce). Support by the hospital staff, particularly, having the opportunity to be counselled by social workers and psychologists, also emerged as a major factor. The caring attitude of healthcare workers was regarded as highly supportive.

The searching brain

Participants sometimes found it difficult to understand the information being given by healthcare workers and the reason for the stillbirth was not always immediately apparent or understood. Informing the patient about the passing of her baby either in utero or shortly after birth is always difficult, especially when the direct cause is not easily identifiable. Participants said that they repeatedly asked the healthcare workers about the cause of their baby's death. Some understood the cause of death, for example, when the doctors informed them that it was due to the complication of their underlying hypertension, while some asked 'could not doctors have known that the babies would demise and should have intervened before it happens?' (Tara). Faith was a response for some when searching for understanding: 'Even though I lost my baby, my God is good all the time' (Tara).

The soul of service

Communication and counselling are components of standard stillbirth care. The participants were divided in their perception of healthcare workers reaching this standard of care. The communication with the healthcare workers was described as comforting by some participants and they were satisfied with the care they received even though they were grieving: 'the fact that the doctors were sympathetic somehow eased the pain' (Adele). This view was not unanimous, however.

The fractured system

Some primiparous participants allocated blame for the stillbirth to the healthcare workers, and felt that they received inferior treatment and care compared with women with live babies. These participants found this treatment upsetting and saw this as a failure of service delivery: 'Women in the labour ward should be treated the same way whether they have alive or dead babies' (Diana). In some cases, a sense of abandonment was evident: 'Why was I not taken for ultrasound on all my appointments, maybe it would have prevented my baby from passing?'(Amina). Participants who had previously delivered live babies did not allocate blame for stillbirths to healthcare workers.

Healthcare workers' perspectives

We interviewed five doctors (four obstetrics and gynaecology registrars and one consultant). Two of the registrars were in the third year, one was in the second year, and one was in the first year. There were three male and two female doctors. We also interviewed the two social workers who service the obstetrics unit and neonatal units at the hospital and seven midwives. Themes that emerged from the healthcare worker interviews were: 'support for women delivering stillborn babies'; 'the overburdened healthcare workers'; and 'the desire to do more'.

Support for women delivering stillborn babies

The prevailing opinion was that the care offered to these women was appropriate in terms of medical management, i.e. starting from when intra-uterine fetal death was diagnosed, the patient was admitted, investigations to establish the cause was conducted and the patient management plan followed. These steps reflect the aspects of medical management outlined in the RCOG Green-top guidelines,[1] but little was mentioned about the healthcare workers' role in the psychological/emotional support of the patient and her family. There was agreement that the current approach emphasised the medical aspect of management over the emotional and psychological aspects. This weakness was identified: 'We are medically managing these mothers appropriately following guidelines. However, doctors need more training in the psychological and emotional aspects of management' (Doctor D). This continued support is within a framework of other possible support such as church members, social workers at their local clinic and families but the '... infrastructure, it is not friendly enough to allow for support from the partner or family during the process' (Nurse M). Overall, the healthcare workers felt that they were offering a good service to women who had experienced a stillbirth: patients, they are actually quite impressed they have been at other hospitals with the same problem and they didn't get the care that we give them here' (Social Worker A).

The overburdened healthcare workers

While medical management and guidelines were deemed to be adequate, follow-up and ongoing support were lacking. Due to the reported large workload and strained capacity in the obstetric unit '.. immediately after delivery, we discharge them or we refer them to social work, from there we don't have the report of the follow-up and we don't do follow-up, we just leave them, we don't know what is happening to them so according to me the care is not enough' (Midwife B).

The prevailing practice included referring the patient to the social worker for counselling post-delivery. There is only one social worker available per day to service the needs of the obstetrics and neonatal units. The social workers believed that the women who had stillbirths were managed appropriately within the guidelines and felt that most women appeared to do well after counselling. This view was supported by patient Lucy who said 'talking to a social worker is reducing this whole emotional burden.'

However, the social workers expressed that they did not have adequate time for follow-up appointments or family counselling for all patients. Follow-up counselling sessions were dependent on referral by the doctors if they noticed that the women were not coping well, and even this was considered to be of limited use: 'they get only one session before we discharge them home, they never get followed up to see how they are coping with the loss of the pregnancy and how they are with their spouses' (Doctor B).

The healthcare participants also expressed the desire for the team to attend counselling sessions with the patient as this would assist them in understanding the patient's needs. However, due to onerous workloads, this is not always possible.

The desire to do more

Participant doctors and midwives believed that they should be more involved in the supportive aspect of care. However, they expressed that they were ill-equipped and did not have the time to engage with the psychosocial aspects of care of these patients: 'yes, the social worker is coming to see the patients; however, it is done by the social worker and patient, the doctor is never part of it. It might be a good idea if it was a multidisciplinary action, where the doctor is there to explain what happened, to answer questions, because if the patient wants to know something, the social worker can't answer all the questions' (Doctor M). There was also an acknowledged need for greater sensitivity towards patients who experienced a stillbirth: 'We do not know how one can react coming to a clinic seeing another patient with a baby. She might think this could have been me holding a baby. I think this is a thing we need to address' (Doctor F). Patients expressed that their faith and beliefs assisted them in coping with experiencing a stillbirth. However, this aspect was not supported in their care provided by the clinical staff: 'lately, we focus so much on the social workers, we don't touch the spiritual aspect of things' (Midwife M).

Discussion

This study explored maternal experiences of care following a stillbirth. The five themes that emerged from the participant data can be loosely grouped to show the maternal experiences of the stillbirth on the one hand and the care received on the other. The themes of 'the broken heart' and 'the searching brain' reflect the participants' responses to the stillbirth, while the 'the helping hand', 'the soul of service' and 'the fractured system' are reflections on the care that they received. These maternal experiences of stillbirth were described as psychological distress due to emotional vulnerability under a heavy mental burden, feeling neglected and fear of uncertainties. The results from the EPDS revealed that all of the participants had varying degrees of depression, ranging from mild to severe depression, and the vast majority scored on the moderate to severe range. The presence of depression among all of the participants is in accordance with previous studies that showed that depression was more common in women who had a stillbirth (14.8%) compared with women who delivered a healthy live baby (8.3%).[10] Heartbreak was a common manifestation among participants, as evidenced by loss of hope, occurrence of worry, anger, self-blame and external blame, all emotions that have been previously described.[4]

Good partner and family support were found to be important ways of reducing psychological trauma, which was also revealed in a study by Human et al.[4] The additional support from counselling services was found to be helpful in this study, which aligns with the findings reported by Mills et al.[11]

Participants tried to make sense of what happened to them, with some depending on faith for answers while others still only had unanswered questions. Searching for reasons for the baby's death and reasons why it happened to them are common reactions.[9]

Good communication and rapport between participants and healthcare workers made the participants feel supported in the difficult situation. This finding was in alignment with the RCOG Green-top guidelines,[1] which encourages healthcare workers to be sympathetic and supportive to mothers with stillbirths at all times. But not all participants viewed the communication as being positive and both the participant doctors and midwives also identified this as a neglected aspect of care.

Participants identified some, in their view at least, system failures. These ranged from opportunities to prevent stillbirths via early ultrasounds to opportunities to provide them with the same level of support as mothers with live babies. Dissatisfaction with the healthcare system was prominent among primigravida participants. This dissatisfaction might be a projection of their disappointment and sense of failure, as well as a lack of a comparative experience. While there is no evidence that more frequent ultrasounds would improve outcomes or that women with stillborn babies receive inferior care, it is recommended that all pregnant women be educated about the symptoms and signs of stillbirth and are aware of the systems in place to manage this complaint consistently so that the potential for adverse outcomes is reduced.[21]

The healthcare participants in the study were of the opinion that the medical treatment was adequate and within the guidelines of the RCOG's Green-top guideline.[1] Even though empathy is an essential trait of a healthcare worker, due to the demanding workload, counselling and emotional support are deferred to social workers and psychologists. The lack of emphasis on the psychological and social aspects such as the collection and preservation of mementos in line with the Green-top guideline among healthcare workers in this present study is a telling omission. Qualitative studies have shown that parents value these mementos and that there are no reports of negative outcomes for doing this.[18-20] The Green-top guideline outlines several practical actions that can be taken in this regard, none of which need training. The lack of emphasis within the healthcare participants in this regard suggests that these actions have not been allocated to anyone in the team. The current system of referring a patient to a social worker after delivery implies that the opportunity to take mementos is lost. The adaptation of the guidelines to include team members responsible for this aspect of care might forefront their importance. Rotations through this unit should be accompanied by an orientation to both the psychosocial and clinical aspects in the revised guidelines.

Study strengths and limitations

The strength of this study was that it was the first such study in our centre that explored the patients' experience of the healthcare system following a stillbirth. However, this study was conducted at a single academic centre, with a small number of participants, over a relatively short period of time. Thus, the experiences of women who experience a stillbirth in either better- or less-resourced settings could be substantially different. While cultural sensitivity was not highlighted in this study, the guidelines do not allow for cultural practices, which is an omission for a diverse population such as ours in SA. More research is required to explore the cultural silence, taboos that typify these issues and their impact on the women.[22]

Conclusion

While the medical aspects of the guidelines were adhered to, the psychosocial aspects were not. Referring patients to a social worker is a 'medical' response and does not encompass what is intended in the guidelines regarding preserving and acknowledging the 'memory' of the lost baby. The guidelines require adaptation, especially taking into consideration African cultural practices. Healthcare workers will also need to do in-service training on these aspects. There is a need to adapt the current guidelines to include allocated responsibility with regard to the application of the psychosocial guidelines as this is the humanitarian umbilical cord between healthcare workers and those in their care.

Declaration. This study was done in partial fulfilment of MMed degree requirements (O&G) for ASJ.

Acknowledgements. We would like to thank all the women who participated in this study.

Author contributions. Equal contributions.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top guideline no. 55. Late intrauterine fetal death. RCOG: London, 2010. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_55.pdf (accessed 20 May 2019). [ Links ]

2. National Department of Health. Guidelines for maternity care in South Africa. NDoH: Pretoria, 2015. [ Links ]

3. Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) Perinatal Mortality (2017). https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports/confidential-enquiry-into-maternal-deaths (accessed 5 April 2019). [ Links ]

4. Human M, Green S, Groenewald C, Goldstein RD, Kinney HC, Odendaal HJ. Psychosocial implications of stillbirth for the mother and her family: A crisis-support approach. Social Work 2014;50(4):392. https://doi.org/10.15270l50-4-392. [ Links ]

5. World Health Organization. Maternal, new-born, child and adolescent health. WHO: Geneva, 2015. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/en/ (accessed 10 June 2019). [ Links ]

6. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance. NICE: London, 2007. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192/resources/antenatal-and-postnatal-mental-health-clinical-management-and-service-guidance-pdf-35109869806789 (accessed 5 April 2019). [ Links ]

7. Robson SJ, Leader LR. Management of subsequent pregnancy after an unexplained stillbirth. J Perinat 2010;30:305-310. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.133 [ Links ]

8. Galtier F, Raingeard I, Renard E, Boulot P, Bringer J. Optimising the outcome of pregnancy in obese women: From pre-gestational to long-term management. Diabetes Metab 2008;34(1):19-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2007.12.001 [ Links ]

9. Redshaw M, Hennegan JM, Henderson J. Impact of holding the baby following stillbirth on maternal mental health and wellbeing: Findings from a national survey. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010996. https://doi.org/10.1136|bmjopen-2015-010996. [ Links ]

10. Gold KJ, Sen A, Hayward RA. Marriage and cohabitation outcomes after pregnancy loss. Paediatrics 2010;125:e1202-e1207. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3081 [ Links ]

11. Mills TA, Ricklesford C, Cooke A, Heazell AEP, Whitworth M, Lavender T. Parents' experiences and expectations of care in pregnancy after stillbirth or neonatal death: A meta-synthesis. BJOG 2014;121(8):943-950. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12656 [ Links ]

12. Meaney S, Everard CM, Gallagher S, O'Donoghue K. Parents' concerns about future pregnancy after stillbirth: A qualitative study. Health Expectations 2017;20(4):555-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12480 [ Links ]

13. Sanchez NA. Mothers' perceptions of benefits of perinatal loss support offered at a major University Hospital. J Perinatal Educ 2001;10(2):23-30. https://doi.org/10.1624/105812401X88165 [ Links ]

14. Gorgi A. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. J Phenomenol Psychol 2012;43(1):3-12. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916212X632934 [ Links ]

15. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2015;42(5):533-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [ Links ]

16. Cox L, Holden JM, Sogonsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782-786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [ Links ]

17. Zhang K, Dai L, Wu M, Zeng T, Yuan M, Chen Y. Women's experience of psychological birth trauma in China: A qualitative study. BMC Preg Childbirth 2020;20:651. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03342-8 [ Links ]

18. Rádestad I, Steineck G, Nordin C, Sjogren B. Psychological complications after stillbirth - influence of memories and immediate management: Population-based study. BMJ 1996;312(7045):1505-1508. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7045.1505 [ Links ]

19. Samuelsson M, Rádestad I, Segesten K. A waste of life: Fathers' experience of losing a child before birth. Birth 2001;28(2):124-130. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536x.2001.00124.x [ Links ]

20. Hughes P, Turton P, Hopper E, Evans CD. Assessment of guidelines for good practice in psychosocial care of mothers after stillbirth: A cohort study. Lancet 2002;360(9327):114-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09410-2 [ Links ]

21. Siassakos D, Jackson S, Gleeson K, Chebsey C, Ellis A, Storey C for the INSIGHT Study Group. All bereaved parents are entitled to good care after stillbirth: A mixed-methods multicentre study (INSIGHT). BJOG 2018;125(2):160-170. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14765 [ Links ]

22. Adebanke A, Min L, Wai C. Sociocultural understanding of miscarriages, stillbirths, and infant loss: A study of Nigerian women. J Intercultural Commun Res 2019;48(2):91-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2018.1557731 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Adam

Sumaiya.adam@up.ac.za

Accepted 28 March 2022