Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.122 n.1 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/122-1-2170

AFRICAN AND GERMAN PERSPECTIVES ON ECOJUSTICE

African Belief Systems and Gendering of Eco-Justice

Susan M. Kilonzo

Department of Religion, Theology & Philosophy, Maseno University, Kenya

ABSTRACT

The African belief system appears to outline concerns and care for the environment, which can form a basis for sustainability. This system also seems to speak to gender roles and responsibilities. The taboo system, for instance, has clear gendered guidelines for human and environmental responsibilities and rights, that appear to be interconnected. A reflection on the African belief system may therefore allow us interrogate and explain the roles of men and women, girls and boys, on climate change, and their response thereto. Since these beliefs and practices are lived side-by-side with modernity, an exploration of gender roles within the belief system may be useful in the overall mainstreaming of the work of men and women in climate change. The article draws from gender perspectives of a few African communities, to show how these perspectives provide varying platforms for addressing or neglecting effects of climate change in the continent, but also how the system affects livelihoods of men and women. Further, the paper explores ways in which the positive approaches can be mainstreamed in state-led approaches to eco-justice for sustainability.

Keywords: Africa Belief System; Climate Change; Eco-Justice; Gender; Intersectionality; Modernity; Sustainability

Introduction

As an African boy or girl growing up 4-6 decades ago, one might reflect and be fascinated by the perspectives of our parents and grandparents on weather and weather changes. We heard them say: ".. .the birds are flying in a certain direction, so we expect rain, or drought; certain plants have started sprouting (especially during dry weather), as a sign of forthcoming rains; sounds of certain animals or insects have been heard, so the beginning or end of the rainy season is here." Your parents or grandparents might have fascinated you with the meanings of sounds of insects and animals for weather patterns; meaning of presence of certain plant species; direction and movement of elements of the sky such as the moon and the sun; or movement of wind, whether whirlwind on dry land or breeze from water bodies (Kilonzo 2022). This is a body of accumulated wisdom, built into a belief system that is important for community and a communal knowledge base and values. This complex body of knowledge, practices, and representations are developed and maintained by peoples through extended histories of interactions with the natural environment. Subsequently, many African communities adopt sustainable practices that minimise harm to the environment. These may include reading of weather patterns, traditional farming methods and natural resource management strategies, and taboo systems that sustain the environment, among others.

African societies are often organised around kinship groups, with individuals' identities and roles within the community strongly influenced by their familial and social relationships (Zegeye and Vambe, 2006). This communal ethos is reflected in many African belief systems, which emphasise the importance of cooperation and mutual support within the community. These systems often emphasise the interconnectedness of humans and the natural world, highlighting the need for a harmonious relationship between the two. Therefore, when one is told not to harvest a certain species of wood, or not to urinate in the forest, as the consequences are unforgiving, these are to ensure some form of balance. Subsequently, within these communities, the belief systems and values determine the day-to-day activities of the community. These diverse and complex African belief systems reflect the continent's diverse cultural and linguistic heritage. It is, however, always important to point out that the concept of indigenous communities and groups has been slowly eroding given tensions between traditional and modern ethos and structures (Bigombe & Khadiagala 1990). Bigombe and Khadiagala (1990) show that there are widespread accounts of families abandoning key traditional practices in favour of modern ones. However, this does not mean a complete erosion of systems that still make sense to Africans, and which in turn help them balance human needs and ecological justice.

Although these belief systems have shaped African societies for a long time, climate change is now threatening them, with rising temperatures and changing weather patterns disrupting ecosystems and food systems across the continent. Nevertheless, the beliefs and practices around weather and weather patterns, and use of indigenous ways of conserving the environment are still in practice (Boyette, Lew-Levy, Jang, Kandza 2022). Further, there have been developments on how the African communities, especially the indigenous communities conserve the environment and interact with animal and plant species. In turn, there are ways in which these communities use the same environment for economic sustainability for their families. This speaks to the holistic approach to ecological justice (Pineda-Pintoa, Herreros-Cantisb, McPhearsonc, Frantzeskakia, Wangf & Zhou 2021).

African belief systems are useful in prioritizing the environment, and this focus on the environment is linked to the concept of eco-justice. Eco-justice refers to the fair and equitable distribution of resources, benefits, and costs related to environmental issues (Bullard, 1994). Eco-justice is a concept that recognises the interconnectedness of social justice and seeks to expose the relationship between impacts, sources, flows, and the impacted places and spaces. It also places the processes and actors of active restoration and reparation of social-ecological interactions at the centre (Pineda-Pintoa, Herreros-Cantisb, McPhearsonc, Frantzeskakia, Wangf & Zhou 2021, Schlosberg, 2012; Schlosberg, 2013). Similarly, Martinez-Alier (2002:13) states that eco-justice is "a concept that reflects the need to integrate environmental concerns with social justice concerns, in order to achieve a more sustainable and equitable world." While defining the term eco-justice, Agbiji (2015) shows that the prefix 'eco' comes from the Greek word for 'house' (oikos) and is part of the etymological root of words like 'economy' and 'ecology', but also 'ecumenism' (WCC 2011). Agbiji (2015:2), while citing Conradie (2003:124) and WCC (2011), further explains, "... with regard to justice, the environmental justice approach, 'eco-justice', challenges both humanity's destruction of the earth and the abuse of power which results in environmental damage, with poor people suffering the greatest impact. This is also embedded within religious doctrines - the need to take care of the environment. African belief systems view the environment as an extension of human life, and therefore the well-being of humans is closely tied to the well-being of the environment (Adepetun & Oluwasola, 2014). This interconnectedness is reflected in many African belief systems, such as the Taboo system, which is found in various African societies and has specific gendered guidelines for human and environmental responsibilities and rights (Leal Filho et al., 2018). For instance, in the Taboo system, certain trees are believed to be sacred, and their destruction is considered taboo. The harvesting of certain plants is only allowed during specific seasons to allow for natural regeneration (Adepetun & Oluwasola, 2014; Kilonzo, Gumo, and Omare, 2009). Even then, some of these practices attract gender dimensions.

Gendered roles are well apportioned for men and women. Although this theme is quite often overlooked when discussing the roles of men and women in conserving the environment (Kilonzo 2022), it remains key in understanding how best to mainstream cultural perspectives of ecological justice. This article therefore, focuses on gender perspectives of African communities, to show how these perspectives provide varying platforms towards addressing or neglecting effects of climate change in the continent, but also how this affects livelihoods of men and women. Further, the paper explores ways in which the positive approaches can be mainstreamed in state-led approaches to eco-justice for sustainability. The first section of the article presents the interconnectedness between African belief systems and eco-justice. The second will explore how gendered roles in eco-justice speak to this interconnectedness, and the final section will provide some summarised recommendations on how this gendered dimension may be used to inform state-led approaches to eco-justice.

African belief systems and eco-justice

African belief systems often outline concerns and care for the environment that may provide sustainability. African cosmology perceives nature as an interconnected system where all living and non-living things are interdependent. This worldview recognises the importance of preserving the environment for the present and future generations. African communities often rely on natural resources for their livelihood, and therefore, there is a strong incentive to preserve the environment (Boyette, Lew-Levy, Jang, Kandza, 2022). Some African scholars have faulted the introduction of Christianity in Africa as a factor to blame for the loss of African belief system. For instance, Werner (2019) cites a West African Theologian who once shared a story with him, that touched on environmental degradation, eco-theology and the role of Christianity in Africa:

The village in the North of Ghana where I grew up was located close to a forest and a river. In the forest from ancient times onwards the ancestors live, therefore it was sacred. In the river there lived the spirit of the water, therefore it was sacred as well. Then people of my village became Christians. Now, according to the new Christian worldview, there were no ancestors anymore in the forest and also there were no spirits anymore in the river. The taboos were disintegrating and disappearing. Instead the people started to make use and exploit both the forest and the water of the river for their own purposes. Today next to this village there is no forest left anymore and the river - it turned into a cesspool. Who has done a major mistake here? And for what reason?" (Emmanuel Anim of the Church of Pentecost Ghana, Accra, story transmitted orally).

In this narrative, the question of the relevance of modern religions in Africa, and in the preservation of African belief systems, and conservation of environment is of the essence. How have Christianity and other foreign religions contributed to the disruption of cultural norms and their influence on the environment and people's livelihoods? How is the African belief system and practices therein, surviving the waves of religious change? Although this essay may not pursue and respond to these questions, they serve to remind the reader that the African belief system is not dead. It lives on and co-exists side by side with other religions.

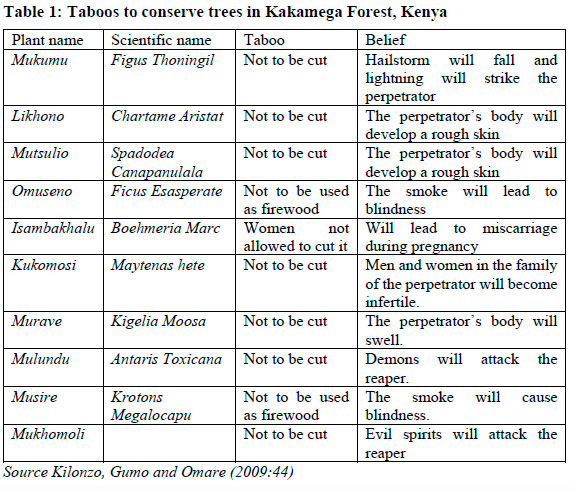

In Africa, the environment is often governed by a combination of formal legal frameworks and informal taboo systems. According to Adepetun (2018), the taboo system is a set of rules and regulations that govern the relationship between humans and their environment. The taboo system recognises the interconnectedness of human and environmental well-being, and therefore eco-justice. For instance, in some African communities, it is forbidden to cut down certain trees or kill certain animals because they are seen as sacred. According to Ntombela and Breen, (2016) these taboo systems are often deeply ingrained in African cultures and may regulate access to natural resources such as water and land, and may also govern the use of certain plants and animals. In some cases, violation of these taboos may be seen as a direct affront to the community and may result in social sanctions, such as ostracism or even physical punishment (Mafico, 2010). Moreover, these informal systems of governance are often shaped by local beliefs and practices and can vary significantly from one community to another. As noted by Gathuru and Githiru (2017), some taboos may be designed to protect sacred sites or to regulate the hunting and fishing practices of a particular community. In contrast, others may be aimed at maintaining ecological balance or conserving certain species of plants and animals. However, it is important to recognise that these informal systems of governance are not always compatible with formal legal frameworks, and conflicts between the two may arise (Ntombela & Breen, 2016). Kilonzo, Gumo and Omare (2009) may help exemplify these. They show why the Isukha community in Kakamega forest preserve certain trees using taboos as seen below:

The taboo system depicted in the table above may prohibit the cutting down of certain trees, while a government may grant licenses to a logging company to do so. Similarly, the Baka and Bayaka (pigmies) of Congo live along the Motaba river along the Congo Forest. However, instead of taking advantage of the forest, they have a way of sustaining a balance using their belief systems. They use the yams that are food for the wild pigs and elephants by harvesting as well as regrowing the same in the forest. They also have warning systems on when to hunt from the forest and when not to hunt. However, the government does not understand this symbiotic relationship and is always pushing the pigmies away from the forest (Boyette, Lew-Levy, Jang, Kandza, 2022). Subsequently, understanding the role of taboo systems in regulating the environment for sustainability and mutual benefits, where humans benefit from the environment while preserving it, is crucial for effective development in Africa, and as a way of ensuring eco-justice. The term eco-justice may be misunderstood in many ways. For instance, Gibson (2004:21) argues that some people may mistake "eco" for economic, and not "ecology"; and others may think that if "ecological justice" stands for environmental justice, then economic justice is overlooked. This, Gibson argues, is not true. Economic justice is very much part of eco-justice. Gibson (2004:21) therefore clarifies,

Sometimes the term has been used to mean only ecological justice, that is, fair and caring treatment of natural systems and nonhuman creatures. We must say, no, it means ecological wholeness and economic and social justice. I have always insisted on the hyphen in eco-justice; it makes the meaning more apparent, the two sides of one concern.

Hessel (2004:xii) also holds that:

an eco-justice ethic views interhuman justice as part of environmental wholeness, because environmental health is inseparable from human well-being. This insight challenges the popular assumption that environmental issues involve caring for an external natural world apart from humans. An eco-justice ethic fosters ecological sustainability as part of, and simultaneous with, social and economic justice.

Ultimately, as shown by Gibson (1985:25),

Eco-justice is the well-being of all humankind on a thriving earth. It is acceptance of the truth that only on a thriving earth is human well-being possible - an earth productive of sufficient food, with water fit for all to drink, air fit to breathe, forests kept replenished, renewable resources continuously renewed, nonrenewable resources used as sparingly as possible so that they will be available for their most important uses as long as possible or until a renewable alternative can be utilized.

The question that lies within this desirable earth is how to balance human needs and ecological sustainability. This, as (Hessel 2004:xiii) argues, requires some form of eco-social analysis that explores the links between ecology and justice. This will allow communities to work on solidarity, sustainability, sufficiency and participation. These practices contain ethical norms and allow for a "both ends-oriented means" - taking care of environment to ensure sustainability while at the same time benefiting from the gains of this sustainability. For this sustainability to be realised, Conradie (2006:156) argues for ecological values, thus:

Environmental problems can only be addressed adequately by ecologically-minded people, people of good moral character, people who embody ecological virtues. Alternatively, one may emphasise the need for appropriate attitudes towards the natural environment.

In the context of African belief systems, values of solidarity, sustainability, sufficiency and participation (Hessel 2004) are to apply, and the need to rethink and educate communities about gendered roles in eco-justice is important.

Gendered roles in eco-justice

The accumulated knowledge that helps African men and women to understand how their environment operates and how in turn they should treat the environment for sustained interrelations is not devoid of gender ethos and norms. A reflection on African belief systems allows us to interrogate and explain the roles of men and women, girls and boys, on climate change, and their response thereof. This is important because these beliefs and practices are lived side-by-side with modernity (Leal Filho et al., 2018), which in the end affects the livelihoods of men and women differently. African communities have traditionally relied on natural resources for their livelihoods, and as such, they are more susceptible to the effects of climate change.

Although women in the African traditional worldview, just like the men, are equipped with the knowledge to understand how nature behaves and what predictions to make using a number of observations, there are gendered provisions for the same. However, it is good to point out that some of the practices are neutral and anyone can participate in the processes. For instance, as Kilonzo (2022:83) shows, women just like men,

... could tell of weather patterns by observing the behaviours of certain elements such as position and movement of the sun, moon, morning dew, flight of birds, and sounds of certain animals. The Kamba in eastern Kenya observe the flying patterns of the Jacobin cuckoo. If they are spotted flying from east to west, this is an indication that the rains are about. Other signs are sprouting and flowering of certain plants, the presence of certain birds and insects, such as crickets, among other signs.

Nevertheless, in these same villages, girls as well as boys, men and women, understood their separate roles, which were vital in ensuring environmental sustainability. When I was growing up in the early eighties, with some exceptions, depending on how traditional or modern the family was, while girls were responsible for collecting firewood, cooking and cleaning, boys took care of cattle. We therefore interacted with the environment in diverse ways and unconsciously were educated by a number of taboos. For instance, girls were not supposed to collect a certain type of wood for cooking -Muteta [which in the Kamba ethnic language translates to iteta, meaning quarrels]. We knew what would happen if we collected this type of firewood, and used it for cooking - the smoke of the firewood would trigger quarrels for recent or past mistakes that the children had been involved in, and this would result in whipping. We therefore avoided it. Smoke from some other types of firewood were also believed to cause blindness. Some of these beliefs are held to date, as the essay will show in a while. In my village, and in the family, boys, given the lightly populated lands knew how to use certain areas as grazing lands while avoiding others that were believed to be abodes of spirits. They also understood the consequences of polluting the environment, and as such avoided open defecation and urination in certain spaces, as consequences would be harsh. Here, warnings included swellings and mysterious diseases on private parts. This applied to girls too. Whether these taboos were given as deterrence for commission of environmental hazards or were truly in respect of divine laws is a question that could and can still be ignored, since the system seemed to serve an important role. But in the context of belief systems, since religion is a matter of faith and belief, these were held, and are still held, to be useful.

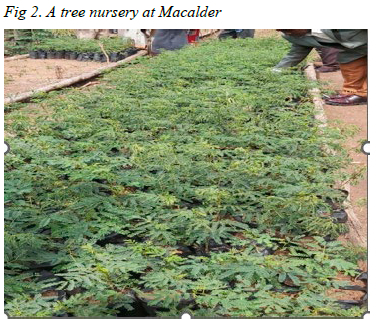

Fast forward, from my village encounters with gendered roles and how taboos influenced our activities, to the month of February 2023. I visit Macalder gold mines, a mining area for locals, in a remote constituency of Nyatike, Migori County, close to the Kenya-Tanzania border. Here we have been doing advocacy work on environmental conservation of gold-mining sites. The picture below is a one among the many mining shafts - used for gold-digging. It is an extremely deep hole, which has to remain open for a long time while the gold-diggers pursue the valuable mineral. Deep inside are poles of wood closely pinned onto the wall of the shaft to avoid any possible collapse of the walls. It is the harvesting of these wooden poles that degrades the environment. Vegetation cover is lost, which then attracts changing weather patterns, including prolonged droughts, flash floods whenever it rains, soil erosion, and other effects. The digging of these holes also interferes with vegetation and limit the use of land for agricultural activities.

Communities here work in groups, and today we are visiting the Community Forest Association (CFA) group in Macalder. Their mandate is to reclaim mining sites by planting trees in the deforested areas as well as their farmlands, and below is an example of a tree nursery that will help them do so.

Settling down to start the discussions, the opening speech is by the chairman of the association. Among the many things he says is that cultural beliefs and practices are important in the drive to conserve the environment. To emphasise, he cites certain facts that touch on gender issues. He gives an example of how women cannot harvest certain trees for firewood, and the women are in agreement that they are aware that such an act would render one barren; and if one is not married, they may never get a spouse. In the 21st Century, one would wonder if gender myths and taboos around certain issues, such as forest conservation, are still applicable. Yes, they are. It also forces us to think through the alternatives that are there for the limitations appropriated by belief systems. For instance, what does not harvesting trees for women mean in the context of their economic welfare? What options do they have?

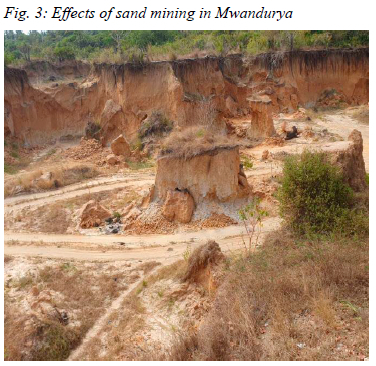

A similar example is given by a different community in the Kenyan Coast, which depends on sand harvesting as their source of livelihood. The Mwandurya Self-Help Group consists of about 27 men, whose sole economic activity is sale of sand. The result of this harvesting is seen in the picture below, that the author took during a visit to the area, in the month of March 2023. Beside this picture of eroded land is another on efforts to regenerate similar sites a kilometer away from the eroded site.

What is noticeable about this group is that unlike the Macalder team, this is a solely male group. The argument is that sand mining is a men's activity, so women cannot be involved. This says a lot about gender roles in economic activities and also in environmental exploitation and degradation, as the section below will show.

The experiences in Macalder and Mwandurya find placement in academic discourse in various ways. In many African belief systems, gender roles are strongly defined, with men and women often assigned specific roles and responsibilities within the community. This gendering of roles extends to environmental roles, with women often playing a central role in the management and protection of natural resources. Scholars argue that taboos play an essential role in shaping the roles of men and women in eco-justice in Africa (Agarwal, 1992). In many African societies, women are the primary caregivers of the environment and have a deep understanding of natural resources management (Nelson & Staley, 2015; Aworinde, 2018). However, gendered taboos limit women's participation in decision-making processes and their access to resources, which negatively affects their ability to contribute effectively to eco-justice initiatives (Okenwa, 2015). Just as we see with the women of Macalder above, in some African communities, women are not allowed to cut down trees or mine other resources, which limits their ability to earn income from the sale of timber or charcoal (Agarwal, 1992; Nelson & Staley, 2015). Similarly, women's access to land and water resources is often restricted by cultural taboos that prohibit women from owning or managing land (Nelson & Staley, 2015). Furthermore, cultural taboos can prevent women from participating in certain economic activities such as logging, mining, or fishing, as seen in the case of Mwandurya, which in turn limits their participation in eco-justice initiatives (Agarwal, 1992). In addition, taboos may prevent women from participating in certain traditional ceremonies and rituals that have an environmental significance, which limits their involvement in environmental decision-making processes (Okenwa, 2015). Other gender roles also curtail the ability of women to engage in other activities, such as attending school or participating in income-generating activities, denying them their rights. For example, women and girls in many African communities are responsible for collecting water and firewood, tasks that can become more difficult and time-consuming as water sources dry up and forests are degraded.

In some African societies, masculinity is associated with the ability to control and exploit natural resources, and environmental conservation is seen as a feminine activity (Mgbeoji, 2015). In some societies, men are prohibited from participating in certain rituals related to natural resource management (Nelson & Staley, 2015). In some contexts, taboos restrict men's involvement in certain environmental practices and traditional knowledge systems (Mgbeoji, 2015), while allowing them to do other activities within the same environment. This can result in men being less likely to support environmental conservation efforts or participate in eco-justice initiatives. Additionally, traditional gender roles can limit men's involvement in household activities, including those related to eco-justice, such as cooking, cleaning, and caring for children (Okenwa, 2015). This can create a division of labour that limits men's participation in eco-justice initiatives and perpetuates gender inequalities, while at the same time burdening women with household chores, and limiting their participation in other economic activities. Women, for instance, are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as droughts and floods, because they are often responsible for providing water and food for their families

Overall, these cultural taboos contribute to gender inequalities in eco-justice initiatives and limit men and women's ability to participate fully in environmental decision-making processes. This may sometimes define the exclusion of men and women from traditional eco-justice initiatives, which in turn limit their ability to contribute to sustainable development in their communities. Addressing these cultural norms and promoting gender equity is crucial to ensuring that both men and women contribute to sustainable development and eco-justice in Africa.

Further, the gender roles shape the ways in which men and women, and girls and boys experience and respond to climate change impacts. Women in traditional farming communities in many African societies are often responsible for planting and harvesting crops, as well as managing the local ecosystem through practices such as agroforestry and soil conservation. These practices are often passed down through generations of women, reflecting the importance of intergenerational knowledge and community cooperation. Despite the important role that women play in environmental management and protection in many African societies, their contributions are often overlooked or undervalued. This can lead to a lack of recognition and support for women's environmental work, as well as a lack of representation in decision-making processes related to environmental issues, which warrants concerns around enhancement of gender mainstreaming in eco-justice perspectives.

Final thoughts: gender mainstreaming for eco-justice

According to Behera and Baka (2021), gender inequalities can exacerbate the impacts of climate change, and the response to climate change can further entrench gender inequalities. Therefore, it is critical to bring gender perspectives into the mainstream in a number of useful platforms and especially the state-led approaches to eco-justice for sustainable environmental, social and economic development. Museka and Madondo (2012:259) argue that one of the ways to do so is through grounding training curricula in unhu/ubuntu philosophy is imperative as it can evoke some kind of environmental awareness which is written "in people's hearts." This is because the religio-cultural beliefs, practices and customs in which the concept of unhu/ubuntu is rooted are not written in books or other readable materials, but engraved in the people's hearts as part of their socialisation. The two further argue that:

... the moral order espoused in the unhu/ubuntu philosophy regulates people's conduct and enables them to recognise and revere the special relationship they have with the physical environment and other non-human species (Museka and Madondo (2012: 259).

Sustaining a unhu/ubuntu philosophy through curricula that passes on the ethos and values of African culture in relation to positive gender roles is important. Important to consider is the role of the national, regional, continental and global infrastructure to eco-justice. If these are supportive of the mainstreaming of gender equality and equity in eco-justice, the processes can be implemented with ease. But this is not usually the case. The national, continental and global pronouncements seem too ignorant of the importance of gender mainstreaming in eco-justice, in their infrastructure. Take an instance of the African Union Commission (AUC 2015) document that resulted from declarations of heads of Africa States who assembled for the 24th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union in January 2015, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. They articulated the mission of the African people on the kind of continent they want - The Africa We Want - by observing their histories. They noted:

Africa is self-confident in its identity, heritage, culture and shared values and as a strong, united and influential partner on the global stage making its contribution to peace, human progress, peaceful co-existence and welfare. In short, a different and better Africa (2015:2).

From this declaration, the need for economic and political development seems to blur the importance that should be accorded to the environment and environmental sustainability as seen in the aspirations below (2015:2):

• A prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development;

• An integrated continent, politically united based on the ideals of Pan Africanism and the vision of Africa's Renaissance;

• An Africa of good governance, democracy, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law;

• A peaceful and secure Africa;

• An Africa with a strong cultural identity, common heritage, values and ethics;

• An Africa, whose development is people-driven, relying on the potential of African people, especially its women and youth, and caring for children;

• Africa as a strong, united, resilient and influential global player and partner.

Seemingly, the focus of the aspirations for the "Africa we want" are mostly on economic, social and political growth. There is little focus on the justice for the ecology and sustainability of Africa. Although in unpacking the aspirations, there is a mention of participating in the climate change debates and initiatives (AUC, 2015:3-4), there is not much discussion about how Africans can use their histories, indigenous knowledge bases and culture for adaptation measures and sustained eco-justice. In fact, the Agenda highly focuses on security, trade, agriculture, movement of people and goods, gender parity and governance. Even when culture is mentioned, the focus is on what has been taken away from Africa, language and identity, religion and socialisation.

Further, in mainstreaming gender perspectives on relevant infrastructure and policies, the need to consider the voices of practitioners and their experiences in the work they do, either as individual persons or organisations, is key. These parties have "lived experience" and are aware of how their involvement in belief systems and gendered roles influence ways in which the environment responds to their activities or inactivities. Finally, there is a need for legal frameworks to largely borrow from the practices entrenched within African communities' belief systems. Of importance is the need for both national and international leadership to recognise the role played by the different belief systems in eco-justice and learn from the good practices that can inform ways in which the indigenous communities may find a place within the recognised legal frameworks, so that pigmies, for instance, can be allowed to live in the forest, protect and benefit from the same forest. This speaks to eco-justice. Such laws and recognition of these communities will be an impetus for them to intensify justice for the environment, which in turn will increase their chances of better livelihoods as they reap from the benefits of a sustained environment.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adepetun, A. & Oluwasola, M. (2014). Gender and environmental conservation in African traditional religion, Journal of Education and Practice 5(9):121-126. [ Links ]

Agarwal, B. (1992). The gender and environment debate: Lessons from India, Feminist Studies 18(1):119-158. [ Links ]

Agbiji, O. 2015. Religion and ecological justice in Africa: Engaging "value for community'' as praxis for ecological and socio-economic justice, HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 71(2), Art. #2663, 10 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i2.2663. [ Links ]

AUC (2015). Agenda 2063: The Africa we want. Africa Union Commission. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia. [ Links ]

Aworinde, D. 2018. The African concept of justice and its implications for sustainable development in Africa, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 20(5):39-53. [ Links ]

Bigombe, B. & Khadiagala, G. 1990. Major trends affecting families in sub-Saharan Africa. Alternativas Cuadernos de trabajo social. 10.14198/ALTERN2004.12.8. [ Links ]

Boyette AH, Lew-Levy S,Jang H, Kandza V. 2022 Social ties in the Congo Basin: Insights into tropical forestadaptation from BaYaka and their neighbours. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377: Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359065997 [accessed Jul 23 2023]. [ Links ]

Bullard, R. D. 1994. Confronting environmental racism: Voices from the grassroots. South End Press. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M., 2003, How can we help to raise an environmental awareness in the South African context?, Scriptura 82:122-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/82-0903. [ Links ]

Conradie, E. 2006. Christianity and ecological theology: Resources for further research. Study guides in religion and theology. Sun Press. University of Western Cape. [ Links ]

Gadgil, M. 2018. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation, Ambio 27(7): 624-629. [ Links ]

Gathuru, G., & Githiru, M. (2017). Traditional ecological knowledge, conservation and management of sacred natural sites in East Africa, Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 13(1):1-12. [ Links ]

Gibson, W. E. 2004. Eco-Justice: What is it? In Gibson, W. (ed.), Eco-justice: The unfinished business. New York: State University of New York Press. , 21-29. [ Links ].

Gibson, W.E. 1985. Eco-Justice: New perspective for a time of turning. In Hessel, D.T. (ed.), For creation's Sake: Preaching, ecology and justice, Louisville, Ky: Geneva Press. [ Links ]

Hessel, D. 2004. Foreword. In Gibson, W. (ed.), Eco-justice: The unfinished business. . State University of New York Press. New York, xi-xvii. [ Links ]

Hessel, D.T. 2007. "Eco-justice ethics." The Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale, 2007. [ Links ]

Karlsson, L. S., & Naess, L. O. 2019. Climate change and gender roles in east Africa: A critical analysis of gender-differentiated impacts and adaptation strategies, Climate and Development 11(7):577-589. [ Links ]

Kilonzo, S. 2022. Women, indigenous knowledge systems and climate change in Kenya. In Chitando, E. Conradie, E. & Kilonzo, S. (eds), African perspectives on religion and climate change. Routledge, 79-90. [ Links ]

Kilonzo, S., Gumo, S., and Omare S. 2009. The role of taboos in the management of natural resources and peace building: A case study of Kakamega forest in Western Kenya, African Journal of Peace 1(2):39-54. [ Links ]

Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A. L., Brandli, L. L., & Özuyar, P. G. 2018. Sustainable development and climate change in African contexts. Springer. [ Links ]

Mafico, T. 2010. Taboo, magic, spirits and religion: An exploration of the relevance of belief systems to the management of natural resources among the Shona of Zimbabwe, International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 6(3-4):135-143. [ Links ]

Martinez-Alier, J. 2002. The environmentalism of the poor: A study of ecological conflicts and valuation. Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Mgbeoji, I. (2015). Men and masculinities in the environment and sustainable development in Africa. In Mitchell, R.H., Crane, R.A. & Schatzberg, M.S. (eds), The Political Ecology of Climate Change Adaptation: Livelihoods, Agrarian Change and the Conflicts of Development. Routledge, 219-240. [ Links ]

Museka, G., and Madondo, M. 2012. The quest for a relevant environmental pedagogy in the African context: Insights from unhu/ubuntu philosophy. A review, Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment 4(10):258-265. [ Links ]

Ncube, M., & Karekezi, S. 2019. Gender roles and climate change: A case of Zimbabwe, Gender and Climate Change in Africa, 73-87. [ Links ]

Nelson, K., & Staley, S. 2015. Gender and natural resource management: Livelihoods, mobility and interventions. Routledge. [ Links ]

Ntombela, T., & Breen, C. M. 2016. The role of taboos in governing the use of natural resources in South Africa, Journal of Environmental Management 181: 777-784. [ Links ]

Okenwa, P. C. (2015). Women and the environment: A gender analysis of rural development and sustainability in Africa, Journal of Gender and Social Issues 14(1):1-22. [ Links ]

Pineda-Pinto, M., Herreros-Cantis, P., McPhearson, T., Frantzeskaki, N., Wang, J. & Zhou, W. 2021. Examining ecological justice within the social-ecological-technological system of New York City, USA. Landscape and Urban Planning 215:104228. [ Links ]

Schlosberg, D. 2012. Justice, ecological integrity, and climate change. In Thompson, A. & Bendik-Keymer, J. (eds.), Ethical adaptation to climate change: Human virtues of the future. The MIT Press, 165-184. [ Links ]

Schlosberg, D. 2013. Theorising environmental justice: The expanding sphere of a discourse, Environmental Politics 22(1):37-55. [ Links ]

WCC, 2011, Social justice and common goods. Policy paper by the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs, working group on social justice and common goods, viewed 20 January 2014, from http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/wcc-commissions/international-affairs/economic-justice/social-justice-and-common-goods-policy-paper. [ Links ]

Werner, D. 2019. The challenge of environment and climate justice: Imperatives of an eco-theological reformation of Christianity in African Contexts. Discussion paper series of the research programme on religious communities and sustainable development. Religion & Development. [ Links ]

Zegeye, A., & Vambe, M. 2006. African indigenous knowledge systems. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 29(4):329-358. [ Links ]