Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Scriptura

versión On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versión impresa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.122 no.1 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/dx.doi.org/10.7833/122-1-2140

ARTICLES

Legal Rights for Non-Human Beings? Theological Impulses for Ecological Justice as a Key Concept of an Ecocentric Ethics

Traugott Jáhnichen

Faculty of Protestant Theology. Ruhr-University Bochum

ABSTRACT

For more than five decades, representatives of the animal liberation movement and of a biocentric or even ecocentric perspective have been demanding that legal rights should be recognised for non-human beings. In 1780, the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham was the first to argue in favour of granting legal rights to animals (cf. Sezgin 2016). More generally, the United States jurist Christopher Stone (cf. Stone 1972) demanded legal rights for trees and for all elements of nature. Such concepts have been legally implemented in a few cases since the beginning of the 21st century, although there are still fundamental questions and differentiating rejections of the idea of legal rights for nature. This article develops a theological-ethical argumentation for the recognition of dignity for non-human beings with the consequence of granting legal rights in an ecocentric perspective.

Keywords: Theocentrism; Integrity of Creation; Sustainability; Dignity of Nature; Participation

Concepts and rejections of legal rights for non-human beings

For many people, the idea of granting rights to non-human beings seems difficult to imagine. By contrast, those in favour of this demand emphasise that the road to the proclamation of human rights, as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, was also extremely lengthy. Even after the proclamation of fundamental rights in the American Declaration of Independence and during the French Revolution, it took almost two centuries before the realisation prevailed that all people, because they were born equal, should be granted the same rights in the life of the state. In fact, in the period from the late 18th to the Declaration of Human Rights, human rights applied primarily to white men. In the period until 1948, all people gradually became included in a universal understanding of human dignity. With regard to certain groups, for example children and people with disabilities, such rights only came into force explicitly in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990) and in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2008). In an analogy to this development, rights are now also claimed for animals and, moreover, for non-human beings in general (cf. Meyer-Abich 1984; Singer 2009, etc.).

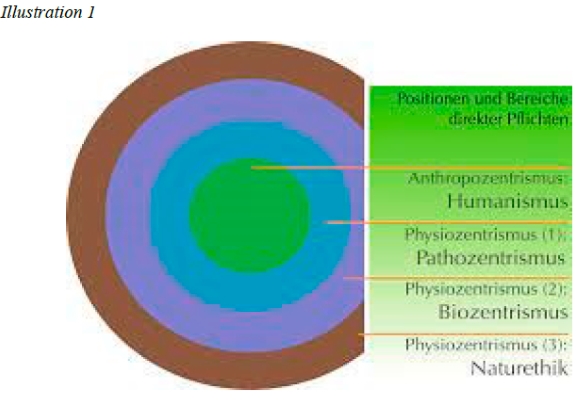

In Germany, Klaus Michael Meyer-Abich has emphatically developed the concept of an "intrinsic value of the natural environment" (Meyer-Abich 1989:254) that goes beyond human interests and needs. Starting from the connectedness of human beings with their natural environment, he emphasises "what is common to human beings and all other living beings, animals and plants, as well as the elements, the communion in which they equally stand" (Meyer-Abich 1989:258). On the basis of this natural interconnectedness, he develops a gradual model of ethics that ultimately includes the entire ecosphere (cf. Illustration 1).

Analogous to the development of the welfare state since the late 19th century, which has clearly minimised the social crises of industrial society, this is to be expanded in view of the ecological survival crisis into an "eco-state". The protection of human dignity should, therefore, be supplemented constitutionally by respect for the intrinsic value of the natural environment. Consequently, as in commercial law which includes companies in the legal sphere as "legal persons" represented by natural persons, living beings and elements of the ecosphere are to be recognised as legal persons too. They should be represented by eco conservation associations or "advocates" of nature (cf. Meyer-Abich 1989:269 f.).

German theologian and former bishop Wolfgang Huber criticises the idea of rights for nature and emphasises that the concept of rights was developed with human persons in mind and that it remains unclear to what extent animals or even natural elements should be recognised as "legal subjects ... (and) how nature itself could assert its rights" (Huber 1996:303). Huber presents an alternative vision by emphasising the distinction between, on the one hand, an anthropocentric responsibility for a biocentric understanding of safeguarding life in order to recognise the dignity of nature and, on the other hand, an anthropocentrism of self-preservation.

Huber argues that there is such a thing as a special dignity of nature. This means that the inherent dignity of nature is not dependent on human recognition but has "its existence in itself (Huber 1996:313). Modifying Kant's concept of dignity, which links dignity to the use of reason, Huber argues in terms of the creation narrative: "All creatures are related to the Creator and dependent on his goodness; all have only a limited living space and a limited life span; all are dependent on ... finding a solution that makes life possible for the individual in the midst of other lives" (Huber 1996:314).

Therefore, humanity must learn to respect nature's own measure, which cannot be replaced by an equivalent. From this follows a biocentric perspective of human responsibility and an ethics of self-limitation, essentially reflected in an "ecological restructuring of the legal order" (Huber 1996:317). Thus, the natural foundations of life are to be protected, and this also means independently of human interests. But the problem exists that sustainability is insufficiently realised, because the "global 'sustainability trilemma'" (Sautter 2017:731) remains unresolved. This trilemma consists of the fact that, by political decisions, "the growth of resource-intensive prosperity is weighted far more highly than the conservation of functioning ecosystems and the implementation of inter- and intragenerational 'justice'", and that there are "up until now no efficient and ethically acceptable solutions" (Sautter 2017:731) for this problem. So, it is necessary to search for impulses to solve these problems. According to a theological perspective, it is necessary to ask in how far the biblical tradition offers impulses for a transition to ecocentrism.

Biblical impulses for the dignity and rights of non-human beings

Contrary to what critics of the biblical tradition assume, the special position of human beings as the image of God (Gen. 1:26 f.) is in no way linked with a disqualification of other forms of life or natural objects. The claim that, according to the Bible, non-human beings are merely "life without a soul" or occupying an ultimately "dead earth" (cf. Blom 2021, cover text) is wrong. This may be partially valid as reflected by the history of Christianity, but it contradicts the biblical testimony.

We should remember not only the participation of the earth in the creation process, which produces not only plants but also living beings of all kinds (cf. Gen. 1:11, 24). Humanity's duty of care for the cattle is explicitly justified by the fact that the just person knows the "soul" or feelings of their cattle (Prov. 12:10). In this sense, biblical traditions also address the deep community of humans and animals, when humans are created together with the land animals on the sixth day (Gen. 1:24-27) and both humans and animals live by the same breath and must return to dust. It remains unclear if there will be a difference between the souls of humans and those of animals after death, as was probably the widespread opinion (cf. Eccles. 3:19-21). We should also remember the eulogies on the wisdom of many animals (cf. Prov. 30:18 f., 24-31; Job 38:36), which owe their insight to God just as much as humans do.

The biblical perspective on animals and other non-human beings goes beyond these wisdom and creation-theological observations. The original relationship of all creatures with God should be remembered, but also that, in the great covenants, human beings and non-human beings are included together in many respects. The covenant with Noah in Genesis 9:9-11 expressly includes "all living beings" (v. 10) on earth, whereby animals are specifically mentioned, but plants may also be considered. This biocentrically designed covenant is in tension with the blessing of Noah and his sons, who are now allowed to rule over the animals and - unlike in the creation story - to eat meat, with the exception of the consumption of blood, the seat of life, which they must renounce (cf. Gen. 9:1-4). Likewise, animals are at least partially included in the covenant at Sinai, when the Sabbath rest, besides the inclusion of all people regardless of their legal and social status, also applies expressly to "your ox or your donkey, or any of your livestock" (Deut. 5:14; cf. also Ex. 20:10). The legal order newly constituted by these covenants is aimed at peaceful coexistence, which, in addition to people, includes livestock in particular, and, in the Covenant of Noah, even includes all living beings. So, the biblical covenants constitute a legal (and even a spiritual) community integrating non-human beings.

This becomes clear with the example of Jonah's judgment sermon in Nineveh and the general penance that followed. The livestock, especially cattle and sheep, should also fast, just as the people put on mourning clothes and all call on God together (Jonah 3:7 f.). Even if there are only a few references, this opens up the perspective of integrating animals into the legal system, and they are credited with playing an active role in the process of turning back to God. Finally, Balaam's donkey (cf. Num. 22:22-35) takes on a very special, even more active role in the communication between God, people, and animals.

While the previous biblical references primarily focused on animals, plants and the field are also treated as objects of human protection in biblical texts, especially in the Sabbath fallow fields (cf. Ex. 23:10 f.), and as subjects too. In the writings of the prophet Joel, the animals and the soil respond with joy to God's restoring action: "Do not fear, O soil; be glad and rejoice, for the Lord has done great things! Do not fear, you animals of the field, for the pastures of the wilderness are green" (Joel 2:21 f.). The end of the horrors of the "Day of the Lord" causes not only people but also animals and even the fields to rejoice. In the book of Job, the field is portrayed as a subject in a different way. In one of his defence speeches, Job makes it clear that his righteousness not only benefits people and animals, but also the field. Otherwise, the field could rightly complain about his mistreatment and react accordingly: "If my land has cried out against me, and its furrows have wept together; if I have eaten its yield without payment, and caused the death of its owners; let thorns grow instead of wheat, and foul weeds instead of barley" (Job 31:38-40). This is where the idea emerges that the field also has a claim to a share of its yields and can sue for this claim. Specifically, this communication is envisioned in such a way that bad or harmful growth alerts people to their failings. Trees are also perceived as subjects, which, in the so-called "taunt song" on the fall of the king of Babylon, join their voices with the joy of the previously oppressed people of Israel and with the rejoicing of all: "The cypresses exult over you, the cedars of Lebanon, saying, 'Since you were laid low, no one comes to cut us down'" (Isa. 14:8). The ancient environmental destruction caused by the clearing of large areas of forest for the needs of the great empires due to their goals of military armament and for the purpose of representation are brought into play here, as is the explicit rejoicing of the trees as soon as such forms of rule come to an end.

Another basic premise of the biblical understanding of creation (cf. inter alia Job 39:5-12; 40:15-41:26; Ps. 104:17 f., 26) manifests in the conviction that not all of creation was created for the benefit of man. In the divine speeches of the Book of Job, as in Psalm 104, creation is "not presented anthropocentrically, but consistently theocentrically" (Ebach 1984:49 f.). From this perspective, for example, the creation of Leviathan (Job 40:25 ff.; Ps. 104:26) is not ordered according to the "principle of purposeful rationality or even just that of utility let alone that of utility from the point of view of man" (Ebach 1984:49). The biblical texts very clearly name the areas of creation that are withheld from being available and usable to humans and correspondingly mark clear limits to the human will to dominate.

In the sense of these biblical remarks, biblical thought embraces the totality of creation - land, plants, animals, and humans. Creation has its own dignity that clearly transcends a purely anthropocentric view. God treats all of creation with benevolence, helps people and animals (Ps. 36:7), gives rain to the earth, lets grass grow, and thus provides food to the cattle and the ravens (Ps. 147:8 f.). This thinking, which encompasses the totality of creation - land, plants, animals, and people - displays a comprehensive communion of all creatures before God. Last, but not least, this means that they are jointly integrated into a comprehensive legal system, which implies a common obligation. This is pointedly expressed in the fact that the essential obligation of all creatures - from the sun and moon to the sea and its inhabitants, weather phenomena, mountains, hills, and trees, then all kinds of animals and finally humans -is to praise the Creator together (cf. Ps. 148). Ultimately, all creation is groaning ... and waiting for salvation (cf. Rom. 8:18-22).

In summary, a considerable biblical tradition acknowledges animals, plants, the field, and even the stars as subjects that communicate with God and with human beings. Of course, these are metaphorical ways of speaking. However, these should not be understood as "inauthentic" forms of speech. Moreover, the metaphorical way of speaking shows the central basic feature of human language, the opening of new perceptions of reality (cf. Ricoeur 2005:109-134). Accordingly, the question must be asked as to what new view of reality is opened up by the biblical forms of speech concerning the role of non-human beings. A consequence for ethics should be respect for every living being and even the ecosphere (cf. Jáhnichen 2021).

Dignity and rights for non-human beings and the ecosphere

The theological perspective of an independent relationship between God and non-human beings, and, therefore, acknowledging the communion of creation, must be introduced into the debates of pluralistic societies as "dignity of nature". Ethically, this means respect for the intrinsic and independent value of non-human beings; the most important consequence being to treat them with justice and even to grant them rights. Consequently, on the one hand, dignity and justice for animals, plants, and the natural elements must be guaranteed. On the other hand, an ethics of the self-limitation of human interests and activities is necessary. According to this perspective, a concept of ecological justice must be developed that must take into account at least four dimensions:

- Participation in the resources of the ecosystem for animals, plants, and natural elements;

- Fair sharing of earnings;

- Ability to live and thrive in a species-appropriate manner;

- Rights for non-human beings.

The right of participation of non-human beings must be specified by a self-limitation on the part of human beings concerning their use of geographical space on earth. One instrument for implementing human self-limitation according to this dimension of justice is to establish national parks and other nature conservation areas, a practice that has existed since the late 19th century (cf. Wustmans 2015:111, 135 f.). It is a matter of great urgency in the present-day situation that nature conservation areas be significantly expanded. For example, more protected rainforest areas and protected sea habitats, even protection for the low Earth orbit, should be implemented. The idea that not all resources are intended for humans must be accepted worldwide. This is necessary because new regulations have to move beyond the establishing of nature conservation areas by single nation-states. International agreements and/or global regulations are necessary. In our time, a first international agreement on the protection of the oceans - beyond national regions - has been signed. Protected areas are one important instrument with which to offer good living conditions for many plants and animals and to conserve biodiversity.

It is a question of justice to give a fair share of earnings to all participants in an economic activity. Such activities are not based solely on human labour. As John Locke points out, 99% of the worth of an economic product is based on human labour and only1% on natural effects (cf. Locke 1759/1962). Some "modern" economists forget the natural share completely; however, there is no economic value chain without an important impact by nature. But how can nature be given a fair share of the economic profit?

Three decades ago, a so-called "eco-tax" was discussed in Germany and in other countries, but never implemented. The idea was to impose a tax on all products that pollute the environment and use the money for renaturation and other environmental protection measures. Today, the European Union (EU) trades in CO2 emission rights. Everyone has to pay for CO2 emissions. The aim is not only to make the emissions more expensive and to avoid emissions in the long run; a fair share of income is also meant to flow back into the protection of nature. According to Job, it is a fundamental question of justice to pay not only the labour, but the field too. It is only now that we are learning to do so.

According to the capability-approach, Martha Nussbaum demands that all animals should have the chance to develop their abilities like human beings do (cf. Nussbaum 2023). In her book Justice for Animals, she advocates the thesis that every animal must be able to live out its species-specific abilities. It is not enough to avoid pain. Instead, we need to take into account all the possible abilities that are part of an animal's normal life. According to Nussbaum, this perspective applies not only to the species but to the individual too. But is it possible to protect insects and other living beings as individuals? Furthermore, Nussbaum does not discuss the questions of plants and their will to thrive. But the ability to live and thrive should be considered for all living beings. For, at least from the point of view of theology, all living beings are part of the communion of creation.

The most difficult aspect of eco-justice is the granting of rights for non-humans. Concerning animals, most legal systems have integrated some rights to protect animals or even care for a species-specific way of living. Some philosophers (cf. Donaldson and Kymlicka 2014) not only propagate negative rights for animals, but also wish to endow them with positive civil rights: domesticated animals are to be treated as citizens, wild animals as sovereign communities, and animals living in cities - pigeons, rats, foxes -should have a right to resident status. This is the most advanced demand with the vision of a new social contract of living together peacefully and fairly with animals.

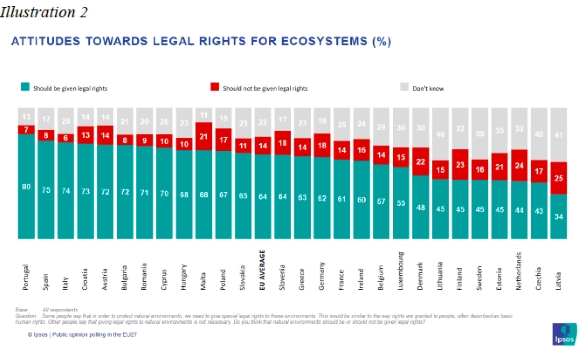

Again, the question of the rights of plants or the natural elements remains unsolved. Nevertheless, two countries have established a legal status for non-human beings, not only for animals: Ecuador in 2008 and Spain in 2022. After a dramatic ecological situation in the lagoon Mar Menor in Spain, the lagoon became the first ecosystem in Europe with a legal status. Any Spanish citizen can file a lawsuit in court to protect the lagoon. The German jurist Jens Kersten argues that "only those who can complain later (or for whom it is possible to complain) will be heard in political decision-making" (cf. Kersten 2014). So, a legal status for non-human beings and even the ecosphere is an instrument of importance that must be developed. Most of the citizens of the EU support this idea (cf. Illustration 2). At the very least, a reversal of the burden of presenting evidence in court is needed: it is not protecting nature that needs to be justified, every kind of damage to nature should be held accountable.

Outlook

The concept of ecological justice tries to integrate aspects of inter- and intragenerational justice among humans - this is the central topic of sustainability - as well as the interests of non-human beings. Of course, the main idea of this concept presented in this contribution must be developed much more precisely. This paper speaks about humans and non-human beings in a generalising and non-specific way. Not all "humans" harm nature in the same way. First, we have to consider many differences between humans: people in the North use far more resources with CO2 emissions than people in the South. There are similar differences between rich and poor people and even between men and women. Of course, these and other dimensions of justice must be considered, as was done during the conference on Ecological Justice in Stellenbosch in March 2023.

Furthermore, the differences between non-human beings should also be noticed. The needs and interests of animals, plants, and the ecosphere vary widely.

Nevertheless, there is a common aim: an ethos of respect for all fellow creatures must be cultivated, as exemplified by the biblical tradition. This attitude corresponds with the recognition of natural dignity that can also be understood by other religious or philosophical traditions. Dignity must be specified in terms of justice concerning participation, a fair share, the ability to live and thrive, and through the granting of legal rights.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blom, Philipp. 2021. Die unterwerfung. Anfang und Ende der menschlichen Herrschaft über die Natur, Munich/Vienna: Hanser. [ Links ]

Donaldson, Sue and Kymlicka, Will. 2014. Tierrechte. In Tierethik. Grundlagentexte herausgegeben von Friederike Schmitz. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. [ Links ]

Ebach, Jürgen. 1984. Leviathan und Behemot. Eine biblische erinnerung wider die kolonisierung der lebenswelt durch das prinzip der zweckrationalität. Paderborn/Munich/Vienna/Zurich: Verlag F. Schöningh. [ Links ]

Huber, Wolfgang. 1996. Gerechtigkeit und recht. Grundlinien christlicher rechtsethik. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. [ Links ]

Jähnichen, Traugott. 2021. Respect for every living being - Theological perspectives on the bioethical imperative. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 77(3), a6775. [ Links ]

Kersten, Jens. 2014. Das Anthropozän-Konzept. Kontrakt, Komposition, Konflikt. Baden-Baden: Nomos Locke, John. 1759/1962. The works of John Locke. Volume 2 (Reprint). Aalen: Scientia Verlag. [ Links ]

Meyer-Abich, Klaus-Michael. 1984. Wege zum frieden mit der natur. Praktische naturphilosophie für die umweltpolitik Munich/Vienna: Hanser. [ Links ]

Meyer-Abich, Klaus-Michael. 1989. Eigenwert der natürlichen Mitwelt und Rechtsgemeinschaft der Natur. In Günter Altner (ed.), Ökologische theologie. Perspektiven zur orientierung. Stuttgart: Kreuz Verlag, pp. 254-276. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, Martha. 2023. Justice for animals: Our collective responsibility.German: Gerechtigkeit für Tiere. Unsere kollektive Verantwortung, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, Paul. 2005. Die metapher und das problem der hermeneutik (1972). In Peter Welsen (trans. and ed.) Vom text zur person. Hermeneutische aufsätze (1970-1999). Hamburg: Meiner, pp. 109-134. [ Links ]

Sautter, Hermann. 2017. Verantwortlich wirtschaften. Die Ethik gesamtwirtschaftlicher Regelwerke und des unternehmerischen Handelns. Marburg: Metropolis Verlag. [ Links ]

Sezgin, Hillal. 2016. Artgerecht ist nur die freiheit. Eine ethik für tiere oder warum wir umdenken müssen. Munich: C.H. Beck. [ Links ]

Singer, Peter. 2009 Animal liberation. The definitive classic of the animal movement. Updated Edition, New York: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Stone, Christopher. 1972. Should trees have standing? - Towards legal. Rights for natural objects, Southern California Law Review 45, 450-501. [ Links ]

Wustmans, Clemens. 2015. Tierethik als ethik des artenschutzes. Chancen und grenzen. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag. [ Links ]