Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.122 n.1 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/dx.doi.org/10.7833/122-1-2117

ARTICLES

Shema as Paradigm (Dt. 6:4-9). The Bible, Education, and the Quest for Development in Contemporary Ghana

Michael Kodzo MensahI, II

IUniversity of Ghana

IIUniversity of South Africa

ABSTRACT

It has been sixty-five years since Ghana, the first black African country south of the Sahara, gained independence from colonial rule. Since then, Ghana can boast of an educational system, which has churned out hundreds of thousands of graduates over the years. Despite these achievements, the country remains poor, raising questions about whether its educational system is fit for purpose. Meanwhile, the moral fibre of society seems to be crumbling with corruption, threatening to thwart any gains made since independence. Given the fact that over 70% of Ghanaians profess Christianity, and the Church's active involvement in education, a resolution of the problem cannot exclude a religious and hence a biblical dimension. This paper, using the distinct interest approach of African Biblical Hermeneutics, argues that Deuteronomy 6:4-9 contains a paradigm for transformative education applicable to the challenges Ghana faces. It demonstrates that the instructions to love YHWH with the whole heart, the whole soul, and the whole might, relate to an education that creatively engages the intellectual faculty, one that is holistic and oriented towards the common good. These are necessary ingredients for the transformation and development of society and equally underscore the role of biblical discourse in building a future for Africa.

Keywords: Shema; Deuteronomy 6:4-9; African Biblical Hermeneutics; Education; Development, Ghana

Introduction

Sixty-six years after Ghana's independence in 1957, the first black sub-Saharan African country to achieve this status, the country is still reeling under the tag of underdevelopment. Several efforts have been made to remedy this situation. In Ghana, for example, the government's flagship policy of providing free secondary education appeared to indicate the country's awareness of the importance of education for development. Unfortunately, studies have shown that the policy, though well-intentioned, has encountered numerous challenges and is unlikely, in this current form, to deliver the transformative agenda Ghana had hoped for (Mohammed & Kuyini, 2020:24-26; Chanimbe & Dankwah, 2021:599).

The inability of formal education to transform African countries has been blamed on several factors. One of these factors is the intellectual gap that exists between the curricula and research of educational institutions and the real existential problems of African peoples (Rocca & Schultes, 2020:3). The continued dependency of African scholarship on Western models and concepts to the detriment of what "fits the needs and realities of African societies" appears to be a problem (Okolie, 2003:247). Another reason is the apparent disconnect between education and the moral formation of the continent's youthful population (Nduku & Makinda, 2014:283-284). In Ghana, research has shown that bribery is more prevalent among educated people, with the most highly educated people being 1.7 times more likely to pay a bribe than those without formal education (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022). A third reason might be attributed to the structural imbalance in the educational sector which appears to lay emphasis disproportionately on the cognitive dimensions of education at the expense of skills acquisition (Bortei-Doku, Doh & Andoh, 2011:6-7). It is little wonder that in Ghana, the import bill continues to spiral out of control, since everything, including toothpicks and tomatoes, is imported for local consumption.

The studies cited above already show a marked interest by several stakeholders to understand and resolve the issues plaguing Ghana's educational sector. Not much, to my knowledge, has been done, however, in interrogating the issues around Ghana's educational debacle from a biblical standpoint. The 2010 Population and Housing Census estimates that 71.2% of the population professes the Christian faith (Ghana Statistical Service, 2023:2). Provision of education by Christian churches is second only to the Government (Ayaga, 2015:40). Any contribution to the dialogue must, however, be premised on sound theological reflection, which is the reason for this engagement with the biblical text. The study, using African Biblical Hermeneutics as a methodological approach will proceed in three steps: First, to conduct an exegetical study of Deuteronomy 6:4-9 to establish the literary structure and key themes in the text; second to identify and explain the principles which this text provides as a basis for holistic and transformative education; and third to show the relevance of these principles for resolving the problems of underdevelopment in Ghanaian society.

African Biblical Hermeneutics and the Distinctive Interest Approach

African Biblical Hermeneutics is defined as "an encounter between the biblical text and the African context" (Ukpong, 2000:3), or "an engagement of scripture from an African worldview" (Amevenku & Boaheng, 2022:61). The rise of this method of reading the Bible occurred in response to the apparent gaps which African scholars perceived between traditional methods of biblical exegesis and the real existential problems faced by Africans and people of African descent (Ukpong, 1999; Adamo, 2015a). Mbuvi, for instance, criticised these traditional approaches for not making the minimal attempt to relate the study of the Bible to present world realities and thus advocated African Biblical studies as a way of resolving the problem (Mbuvi, 2017:152). Adamo argued in the same vein for the need for an approach to the study of the Bible that is vital for the well-being of African society and which has the capacity to transform the continent (Adamo, 2015b:33).

African biblical scholars have proposed several approaches to the reading of the Bible within the African context. These include the Communal Reading, the Bible as Power, the Africa and Africans in the Bible, the African Comparative and Evaluative, and the Distinctive Interest approaches, among others (Adamo, 2015b:36-45). This study adopts the Distinctive Interest Approach. Adamo (2015b:45) explains this approach as one in which the reader brings to the reading of the Bible "interpretative interests and life interests". These interests may relate to religious, cultural, or socio-political commitments. Mbuvi defends the legitimacy of this approach by arguing that "in the African religious reality, no distinction exists between the sacred and profane, between the spiritual and physical" (Mbuvi, 2023:79). This makes it entirely possible, within the African worldview, to bring what others might perceive as secular interests into the sphere of religion. The Distinctive Interest approach is thus particularly suitable for this study in as much as it permits the researcher to engage questions of development and education in Ghana from the perspective of a religious text, in this case, the Bible. The approach will involve first examining the biblical text and then bringing the results of this study into dialogue with a critical evaluation of the reality of education in contemporary Ghana.

Education and Development and the Shema

Education has been defined as "the act of transferring knowledge in the form of experiences, ideas, skills, customs and values from one person or another or from one generation to generations" (Adu-Gyamfi, Donkoh & Addo, 2016:158). Such transfer of knowledge, which is all-encompassing, economic, socio-cultural, religious, and moral, is intended to ensure that younger generations are equipped with the tools required not simply for survival but for the advancement of society. Development, on the other hand, may be defined as a process of transforming the economic, political, and sociocultural conditions of a society by harnessing its resources effectively to deliver improved quality of life for all its citizens (Rabie, 2016:8). The correlations between education and development have been the subject of several studies. Thus, Gylfason asserts, for instance, that "Education is good for growth" (Gylfason, 2001:858), while Cinnirella and Streb equally affirm the positive correlation between education and the transition to modern economic growth (Cinnirella & Streb, 2017:193-194).

The legitimate question to be asked is what Shema (Dt. 6:4-9) has to do with education and development. The interest of the passage, Deuteronomy 6:4-9, in education is one that has sufficiently been established by scholars (Huebner, 1985:461; Isbell, 2003:109-110; Andor & Quaye, 2014:21-32; Van Niekerk & Breed, 2018:7). What perhaps requires some justification is the relevance of the Shema to the subject of development. This is not too difficult to establish from a purely synchronic point of view. The Shema (Dt. 6:4-9) has as its immediate context Deuteronomy 6:10-25, which details the prescribed conduct of Israel when they enter the promised land. The first two verses (Dt. 6:10-11) are particularly important. They relate to the conditions in which YHWH will keep his people in the promised land if they remain faithful to the Torah. These conditions, which include cities (v. 10), agricultural produce, and water resources (v. 11), guarantee the well-being of the people. Moreover, obedience to the Torah also assures Israel liberty (v. 12) and socio-political stability (v. 15). All of this depends on the ability of Israel to assimilate all that they have been taught (v. 17), summarised in the preceding passage, the Shema (vv. 4-9). It would appear then that the Shema provides the content and the manner of that education that is necessary for the development of an economically prosperous and socio-politically stable nation of Israel in the promised land. The Shema defines the knowledge that a nomadic people will need to prosper when they become settlers in the land of Canaan.

The Shema as a Paradigm for Transformative Education

The Shema (Dt. 6,4-9), has been described as the foundation of the Jewish faith, and is an exhortation to Israel to acknowledge YHWH as its God (Veijola, 1992a:369; Crouch, 2016:116). Elements of this exhortation, today recited by observant Jews as a morning and evening prayer, already appear with variations in other parallel texts in the Hebrew Bible (Num. 15:37-41; Dt. 11:13-21) and in the New Testament (Mt. 22:37; Mk. 12:30; Lk. 10:27). The greater proportion of scholarly work on the Shema has concentrated on the redactional history of the text, with Deuteronomy 6:4-5 widely being considered as belonging to the earliest stratum of the Book of Deuteronomy (Seters, 1999:103; Römer, 2004:170). Similarly, issues of syntax in Deuteronomy 6:4 (Kraut 2011) have led to divergences in opinion as to whether the Shema is a profession of mono-Yahwism, a rejection of the plural manifestation of Yahwistic cults in Israel (Driver, 1902:90), of monolatry, the insistence in the worship of Yahweh alone while not denying the existence of other deities (MacDonald 2017:779), or of strict monotheism which asserts the existence only of Yahweh as God (Veijola, 1992b:536; Bord & Hamidović, 2002:25).

Beyond these questions, however, scholars have equally pointed out the pedagogical importance of the passage Deuteronomy 6:4-9 (Huebner, 1985:461; Isbell, 2003:109-110; Andor & Quaye, 2014:21-32; Van Niekerk & Breed, 2018:7). The passage does not only set forth the fundamental elements of the Jewish faith but insists on the method of instruction, those to be instructed, and even the time of instruction. The nature of the instruction the text prescribes is however not a matter of absolute consensus. Isbell (2003:109) suggests that the text implies "a mechanistic method of rote very similar to simple repetition", an observation which is not particularly complimentary. Andor and Quaye (2014:22) are perhaps more deferential in suggesting that the text contains a proposal of "wholistic education". Birch (1983:30-31) lays the emphasis on something else, proposing that the passage stresses the home as the "central agency for education", while Brueggemann (1985:172) curiously prefers Deuteronomy 6:20-21 as a starting point for his discussion on the education in the Bible. What is clear is the lack of unanimity of scholarly opinion regarding the origins and functions of the passage Deuteronomy 6:4-9, which warrants another look at the text and its implications for conceptualizing education in Israel.

The Structure of the Text Deuteronomy 6:4-9

The passage Deuteronomy 6:4-9 has mostly been divided into two parts, 6:4-5,6-9. The reasons for this division have mainly been redactional, vv. 4-5 having been seen as introducing the so-called Urdeuteronomium in Deuteronomy 12-26 and concluding in Deuteronomy 28 with the first set of blessings and curses (Römer, 2004:170). Weinfeld (2008:328) similarly proposes that vv. 4-5 be understood as a declaration of faith, v. 7 as an injunction to educate the children through the monotheistic creed, and vv. 8-9 as the injunction to memorise the words through the use of phylacteries and door inscriptions. The difficulty, admittedly, is where to place v. 6. If the phrase  (hadde ḇārîm hāēlleh) belongs to the preceding vv. 4-5, the passage could very well be divided vv. 4-6,7-9. If, however, it refers either to the decalogue in Deuteronomy 5 or to the entire book, it could very well remain in vv. 6-9 (Nelson, 2004:91).

(hadde ḇārîm hāēlleh) belongs to the preceding vv. 4-5, the passage could very well be divided vv. 4-6,7-9. If, however, it refers either to the decalogue in Deuteronomy 5 or to the entire book, it could very well remain in vv. 6-9 (Nelson, 2004:91).

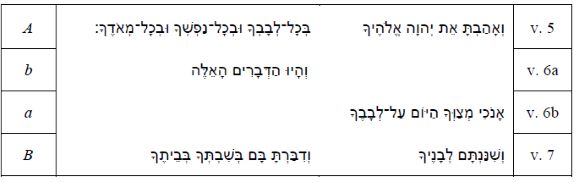

Another possibility, however, is to understand v. 6 as being a transitional verse that employs linked keywords in bridging two textual units, according to the pattern Parunak (1983:532) describes as Ab/aB, as illustrated below:

As the above illustration shows, the term  (lēḇāḇ, heart) in v. 5b is repeated in v. 6b, while the radical

(lēḇāḇ, heart) in v. 5b is repeated in v. 6b, while the radical  (đḇr) in v. 6a recurs in v. 7b, such that the paragraphs vv. 4-5 (A) and vv. 7-9 (B) are knit together in v. 6, by the repetition of the linked keywords

(đḇr) in v. 6a recurs in v. 7b, such that the paragraphs vv. 4-5 (A) and vv. 7-9 (B) are knit together in v. 6, by the repetition of the linked keywords  /

/  (lēḇāḇ / dāḇār). The above has implications for understanding the unity of the passage Deuteronomy 6:4-9. The first part vv. 4-5 deals with the content of the instruction, namely the Shema, while the second part (vv. 7-9) contains the manner of the instruction, with v. 6 acting as a transitional verse between these two parts.

(lēḇāḇ / dāḇār). The above has implications for understanding the unity of the passage Deuteronomy 6:4-9. The first part vv. 4-5 deals with the content of the instruction, namely the Shema, while the second part (vv. 7-9) contains the manner of the instruction, with v. 6 acting as a transitional verse between these two parts.

The Contents of the Shema (Dt. 6:4-5)

Exegetical debates over the Shema, as already mentioned above, centre around the questions regarding Mono-Yahwism, Monolatry and Monotheism in Deuteronomy 6:4. Bade argues that Deuteronomy 6:4 is an argument against the proliferation of Yahwistic cults akin to the Baal cults of Israel's neighbours (Bade 1910:81-83; Hoffken 1984:88-90). Bord and Hamdović (2002:25-26) and similarly Veijola (1992b:536) deny any evidence from the text suggesting Mono-Yahwism and insist that the context of Deuteronomy 6 suggests strict monotheism. Peter (1980:261) and MacDonald (2017:779) argue to the contrary, that references to other gods are found throughout the Book of Deuteronomy (4:19; 6:14; 7:4; 29:17; 31:18), which should eliminate the idea of monotheism in the modern sense. Israel's devotion is reserved for YHWH her God (monolatry), to the exclusion of the gods of the nations.

The relationship between v. 4 and the subsequent v. 5 is equally a matter of debate. Scholars like de Moor (1994:190 argue for a division between the two verses. Veijola disagrees, arguing that Deuteronomy 6:5 is a theological commentary on v. 4, in which the emphasis on "love" ( , āhaḇ,) refers to the exclusive loyalty to Israel's only God (Veijola, 1992a:379). Herrmann (2000:54) similarly argues the uniqueness of YHWH, (

, āhaḇ,) refers to the exclusive loyalty to Israel's only God (Veijola, 1992a:379). Herrmann (2000:54) similarly argues the uniqueness of YHWH, ( eḥāḏ) mentioned in v. 4b, requires undivided loyalty to him in v. 5. The above positions are reinforced by the use of the language of totality (

eḥāḏ) mentioned in v. 4b, requires undivided loyalty to him in v. 5. The above positions are reinforced by the use of the language of totality (  , kōl) employed in the command to love YHWH in v. 5. (König, 1897:27) Israel is to love YHWH with her whole heart (

, kōl) employed in the command to love YHWH in v. 5. (König, 1897:27) Israel is to love YHWH with her whole heart ( ), with her whole soul (

), with her whole soul ( , nepheš) and with her whole might (

, nepheš) and with her whole might ( , me'ōḏ).

, me'ōḏ).

The triad, heart, soul, and might, occurs only twice in the Hebrew Bible, in Deuteronomy 6:5 and in 2 Kgs. 23:25. Grisanti (2012:192) insists that these terms are "relatively synonymous terms" which Moses piles up, and denies further that the terms express "precise modes of expressing love or refer to three distinct spheres of life". These claims deserve to be re-evaluated. The use of the terms  and

and  as a word pair is attested (Dt. 4:29; 10:12; 11:13; 13:4; 26:16: 30:2.6.10). However, the substantive

as a word pair is attested (Dt. 4:29; 10:12; 11:13; 13:4; 26:16: 30:2.6.10). However, the substantive  is never used in parallel or as a word pair for either term. The idea that these three terms are used as synonyms is therefore without a firm basis. Synonymity is only one possibility among a variety of other relationships which could connect the three terms.

is never used in parallel or as a word pair for either term. The idea that these three terms are used as synonyms is therefore without a firm basis. Synonymity is only one possibility among a variety of other relationships which could connect the three terms.

Heart, Soul, and Might in Deuteronomy 6:4-5

The term  (heart) occurs in the Hebrew Bible 853 times and 51 times in the Book of Deuteronomy (Fabry, 1995:407). It refers to the body organ, the heart (1 Sam. 25:37; 2 Sam. 18:14; Ps. 3:7) but is also used in a range of expressions to denote the "midst" (Ex. 15:8; Pro. 23:34; Ezk. 27:4; Ps. 46:3). While the Hebrew Bible attributes physical and psychological functions to the heart (Gen. 18:5; Jdg. 19:5; 1 Sam. 1:8; Isa. 1:5 Pro. 14:10). Wolff notes that "in by far the greatest number of cases, it is the intellectual, rational functions that are ascribed to the heart" (Wolff, 1974: 46). Kruger similarly observes that whereas in modern languages the heart is the organ of feeling and the head of thinking, the Hebrew Bible conceives of the heart primarily as the organ of thought (Kruger, 2009: 104). It is for this reason that Wolff concludes that the heart

(heart) occurs in the Hebrew Bible 853 times and 51 times in the Book of Deuteronomy (Fabry, 1995:407). It refers to the body organ, the heart (1 Sam. 25:37; 2 Sam. 18:14; Ps. 3:7) but is also used in a range of expressions to denote the "midst" (Ex. 15:8; Pro. 23:34; Ezk. 27:4; Ps. 46:3). While the Hebrew Bible attributes physical and psychological functions to the heart (Gen. 18:5; Jdg. 19:5; 1 Sam. 1:8; Isa. 1:5 Pro. 14:10). Wolff notes that "in by far the greatest number of cases, it is the intellectual, rational functions that are ascribed to the heart" (Wolff, 1974: 46). Kruger similarly observes that whereas in modern languages the heart is the organ of feeling and the head of thinking, the Hebrew Bible conceives of the heart primarily as the organ of thought (Kruger, 2009: 104). It is for this reason that Wolff concludes that the heart  especially when conceived of as the seat of reason, is to be "clearly distinguished from nepeš" (Wolff, 1974:46-47).

especially when conceived of as the seat of reason, is to be "clearly distinguished from nepeš" (Wolff, 1974:46-47).

The term  (soul) occurs 754 times in the Hebrew Bible and 35 times in the Book of Deuteronomy (Seebass, 1998:502). The term has a wide range of applications referring to the breath of throat (Isa. 5:14; Hos. 2:5), a desire or wish (Dt. 23:25; Hos. 9:4), the soul (Dt. 4:29;12:20; 2 Sam. 5:8; Isa. 1:14), life, a living being (Lev. 27:2; Dt. 24:7), or even a corpse (Lev. 19:28). The term is also rarely applied to God (Am. 6:8; Ezk. 23:18). The Greek Septuagint in most cases translates the term ψυχή (soul) with an understanding distinct from the Platonic dualist concept (Seebass, 1998:503).

(soul) occurs 754 times in the Hebrew Bible and 35 times in the Book of Deuteronomy (Seebass, 1998:502). The term has a wide range of applications referring to the breath of throat (Isa. 5:14; Hos. 2:5), a desire or wish (Dt. 23:25; Hos. 9:4), the soul (Dt. 4:29;12:20; 2 Sam. 5:8; Isa. 1:14), life, a living being (Lev. 27:2; Dt. 24:7), or even a corpse (Lev. 19:28). The term is also rarely applied to God (Am. 6:8; Ezk. 23:18). The Greek Septuagint in most cases translates the term ψυχή (soul) with an understanding distinct from the Platonic dualist concept (Seebass, 1998:503).

A point of consensus among scholars suggests that the term  bears the nuance of entire human person, both corporeal and non-corporeal. Grisanti (2012:191) explains that the term designates "one's entire being or person", while Bruckner (2005:11) argues that the term is the "Hebrew concept of the whole person", that is, "a living physical being in relation to others". An important dimension of the person

bears the nuance of entire human person, both corporeal and non-corporeal. Grisanti (2012:191) explains that the term designates "one's entire being or person", while Bruckner (2005:11) argues that the term is the "Hebrew concept of the whole person", that is, "a living physical being in relation to others". An important dimension of the person  is the necessity of a rapport with the other. Nelson (2004:91), for instance, argues that the term "represents the closest possible personal rapport" (1 Sam. 18:3; 20:17). Seebass (1998:511) admits that this relationship could refer "directly to the relationship between God and the individual", though he argues that this is rarely the case (Ps. 63:9). Otto points out that the term

is the necessity of a rapport with the other. Nelson (2004:91), for instance, argues that the term "represents the closest possible personal rapport" (1 Sam. 18:3; 20:17). Seebass (1998:511) admits that this relationship could refer "directly to the relationship between God and the individual", though he argues that this is rarely the case (Ps. 63:9). Otto points out that the term  (love) and

(love) and  (soul) both belong to the Ancient Near Eastern vocabulary of loyalty characteristic of the covenant relationship between vassals and kings (Otto, 1999:363). This underscores the emphasis on the relationship between Israel and YHWH in the expression

(soul) both belong to the Ancient Near Eastern vocabulary of loyalty characteristic of the covenant relationship between vassals and kings (Otto, 1999:363). This underscores the emphasis on the relationship between Israel and YHWH in the expression  (ȗḇkol-naṗšekā, and with all your soul) in v. 5b. Moreover, the slightly modified expression

(ȗḇkol-naṗšekā, and with all your soul) in v. 5b. Moreover, the slightly modified expression  (bekol awwat naṗšekā, with all the desire of your soul) appears in Deuteronomy 12:15,20 within the context of the centralisation of the cult in Deuteronomy 12-13. As Otto observes, Deuteronomy 6:4-5 and Deuteronomy 12:13-27 appear to be bound by similar concerns about the command to be loyal to one God, and to preserve a single sanctuary for his worship (Otto, 1999:364). This being the case, the command to love YHWH "with all your soul" is essentially an injunction for a complete and total self-giving of the entire person in his rapport with YHWH.

(bekol awwat naṗšekā, with all the desire of your soul) appears in Deuteronomy 12:15,20 within the context of the centralisation of the cult in Deuteronomy 12-13. As Otto observes, Deuteronomy 6:4-5 and Deuteronomy 12:13-27 appear to be bound by similar concerns about the command to be loyal to one God, and to preserve a single sanctuary for his worship (Otto, 1999:364). This being the case, the command to love YHWH "with all your soul" is essentially an injunction for a complete and total self-giving of the entire person in his rapport with YHWH.

The third element in the triad,  (might), as a substantive, is even rarer in the Hebrew Bible, appearing only in 2 Kgs. 23:25 apart from Deuteronomy 6:5. The adverbial form, which is much more common in the Hebrew Bible is often translated "very" or "exceedingly" (Bruckner, 2005:14). The Greek Septuagint in Deuteronomy 6:5 translates the term as δύναμς; (might or force), while in 2 Kgs. 23:25, the same term is rendered

(might), as a substantive, is even rarer in the Hebrew Bible, appearing only in 2 Kgs. 23:25 apart from Deuteronomy 6:5. The adverbial form, which is much more common in the Hebrew Bible is often translated "very" or "exceedingly" (Bruckner, 2005:14). The Greek Septuagint in Deuteronomy 6:5 translates the term as δύναμς; (might or force), while in 2 Kgs. 23:25, the same term is rendered  (strength). Other ancient versions, such as the Aramaic Targum Onqelos, reads

(strength). Other ancient versions, such as the Aramaic Targum Onqelos, reads  (bkl-nksk, with all your property) (Sifre Dt. 32; Mishnah Berakhot 9:5), while the Syriac versions read qnyn (wealth) in Deuteronomy 6:5b, thus interpreting the Hebrew

(bkl-nksk, with all your property) (Sifre Dt. 32; Mishnah Berakhot 9:5), while the Syriac versions read qnyn (wealth) in Deuteronomy 6:5b, thus interpreting the Hebrew  as referring to wealth or property. Subsequent closer consideration of the wider context of Deuteronomy 6:4-9 would give further reason to view this latter option as a plausible meaning of the term.1

as referring to wealth or property. Subsequent closer consideration of the wider context of Deuteronomy 6:4-9 would give further reason to view this latter option as a plausible meaning of the term.1

The manner of Instruction of the Shema (Dt. 6:7-9)

The pedagogical value of Deuteronomy 6:7-9 has been noted by scholars (Van Niekerk & Breed, 2018:8-9). Ayuk (2017:95) compares the manner of instruction in the passage to the principles of Psycho-social methodology. Van Niekerk & Breed (2018:8-9) also argue that the instruction is based on the principles of diligence, regularity, and pragmatism. Beyond the above observations, it is possible to identify three dimensions of education at which the instructions in Deuteronomy 6:7-9 appear to be directed. Deuteronomy 6:7a opens with the rather rare verb  (šinnēn, to repeat, whet, sharpen). The use of this verb, instead of its synonym

(šinnēn, to repeat, whet, sharpen). The use of this verb, instead of its synonym  (limmad, teach), in Deuteronomy 11:19, lays emphasis here on repetition (MacDonald, 2017:780). The mode of instruction is further defined as verbal, with the use of the piel verb

(limmad, teach), in Deuteronomy 11:19, lays emphasis here on repetition (MacDonald, 2017:780). The mode of instruction is further defined as verbal, with the use of the piel verb  (dibbēr, speak) in v. 7b, signalling an intensification. Moreover, Grisanti (2019:193) notes that the use of the word pairs, "sit" and "walk", "lie down" and "get up" (v. 7cd), constitute a merismus, indicating that the instruction is to be given constantly and repetitively. What comes across in v. 7 is therefore an emphasis on a cognitive or intellectual dimension of education, aimed at equipping the child with the knowledge of YHWH's law.

(dibbēr, speak) in v. 7b, signalling an intensification. Moreover, Grisanti (2019:193) notes that the use of the word pairs, "sit" and "walk", "lie down" and "get up" (v. 7cd), constitute a merismus, indicating that the instruction is to be given constantly and repetitively. What comes across in v. 7 is therefore an emphasis on a cognitive or intellectual dimension of education, aimed at equipping the child with the knowledge of YHWH's law.

A second dimension of education emerges in v. 8. Much of the scholarship on this verse interrogates the question of whether these practices of binding the instruction on the hands, between the eyes should be considered literally or metaphorically (Craigie, 1976:159; Veijola, 1992b:537; Tigay, 1996:443). More importantly, Nelson (2004:92) cites the wearing of objects on the arm as a religious expression, performed to demonstrate a person's relationship or association with a deity, as well as the wearing of inscribed headgear by persons who had a role to play in Israel's cultic life (Ex. 28:36-38). Tigay (1996:443) also considers the wearing of tefillin as part of a "small stock of religious symbols" permitted in the Book of Deuteronomy, a tradition that ordinarily promotes a more abstract form of religion. Similarly, Driver (1902:92) suggests that the wearing of the tefillin was "to serve as an ever-present memorial to the Israelite of his relationship to Jehovah". Perhaps even more important to the above discussion is the mention in v. 8 of the hand ( , yādekā) and the eyes

, yādekā) and the eyes  , 'ênêkā). The reference to these parts of the body could very well be a case of pars pro toto. The education of the child in Deuteronomy 6:8 is thus directed at the entire human person, one which prepares him for an intimate rapport with YHWH.

, 'ênêkā). The reference to these parts of the body could very well be a case of pars pro toto. The education of the child in Deuteronomy 6:8 is thus directed at the entire human person, one which prepares him for an intimate rapport with YHWH.

A third dimension of the instruction in Deuteronomy 6:7-9 is found in the writing on the doorposts of the house and the gates in v. 9. Scholarly reading of v. 9 often considers it closely joined to v. 8 as a continuation of the instruction, and similarly treats the question of the mezuzot as either metaphorical or literal (Craigie, 1976:159; Grisanti, 2012:194). Another line of reading has been to consider the practice of the mezuzot as having apotropaic functions (Nelson, 2004:92; Frevel, 2012). Particularly worthy of note, meanwhile, is the observation that in Deuteronomy 6:9, the passage deals no longer with parts of the human body but switches to the house ( , bêtekā) and the gates (

, bêtekā) and the gates ( , še 'ārêkā). The term

, še 'ārêkā). The term  (bayit) primarily refers to a dwelling or building (Gen. 33:17; Dt. 6:7, 20:5; Ps. 118:22). The term could, however, also refer to a palace (Gen. 12:15; 2 Sam. 7:2), a temple (Jdg. 17:5; Dan. 1:2), or even a family (Josh. 24:25; Ps. 115:10). Quite importantly, the term is also used to designate the things which are in the house, namely possessions, servants, cattle or simply wealth (Ex. 20:17; Gen. 30:30; Num. 24:13) (Hoffner, 1975:113-115). The use of the same term

(bayit) primarily refers to a dwelling or building (Gen. 33:17; Dt. 6:7, 20:5; Ps. 118:22). The term could, however, also refer to a palace (Gen. 12:15; 2 Sam. 7:2), a temple (Jdg. 17:5; Dan. 1:2), or even a family (Josh. 24:25; Ps. 115:10). Quite importantly, the term is also used to designate the things which are in the house, namely possessions, servants, cattle or simply wealth (Ex. 20:17; Gen. 30:30; Num. 24:13) (Hoffner, 1975:113-115). The use of the same term  in v. 7b however suggests that this use here refers to a family dwelling. The term

in v. 7b however suggests that this use here refers to a family dwelling. The term  (ša'ar)"is not used for the entrance to a domestic building" (Otto 2006:370) but usually refers to the portals of a city (Dt. 11:20), of the temple (Ps. 24:7); or the palace complexes (Jer. 22:2). Importantly, the city gates where often synonymous of the courts of the place where legal justice was dispensed (Dt. 21:19; Rt. 4:1). While placing writing upon the doors of the house is entirely plausible, Derby (1999:40) has cautioned against taking the writing on the city gates too literally, arguing that such a practice has never been corroborated by archaeology nor would it have been meaningful. While not disregarding Derby's caution, it might be equally plausible to suggest that the terms "house"

(ša'ar)"is not used for the entrance to a domestic building" (Otto 2006:370) but usually refers to the portals of a city (Dt. 11:20), of the temple (Ps. 24:7); or the palace complexes (Jer. 22:2). Importantly, the city gates where often synonymous of the courts of the place where legal justice was dispensed (Dt. 21:19; Rt. 4:1). While placing writing upon the doors of the house is entirely plausible, Derby (1999:40) has cautioned against taking the writing on the city gates too literally, arguing that such a practice has never been corroborated by archaeology nor would it have been meaningful. While not disregarding Derby's caution, it might be equally plausible to suggest that the terms "house"  and "gates"

and "gates" used in v. 9 evoke more than simply the physical structures on which the writing of the instruction is to be done. It could suggest here the application of YHWH's command to two dimensions of the secular sphere, namely to all that the individual superintends or possesses in the domestic life (JVZl) and to the maintenance of just relations in the wider social sphere

used in v. 9 evoke more than simply the physical structures on which the writing of the instruction is to be done. It could suggest here the application of YHWH's command to two dimensions of the secular sphere, namely to all that the individual superintends or possesses in the domestic life (JVZl) and to the maintenance of just relations in the wider social sphere  .

.

Three Key Concepts of the Shema Instruction

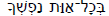

The discussion regarding the two parts of Deuteronomy 6:4-9 permits a synthesis of the two parts of the text, vv. 4-5 and 7-9, revealing three dimensions of the command to love YHWH in Dt. 6:5 as illustrated below:

The above illustration indicates the three concepts which form the core of the Shema. The instruction to love with the whole heart  is illustrated in v. 7 by the command to drill YHWH's word into the memory of the child by repetition, an activity which is largely intellectual. The command to love with the entire soul

is illustrated in v. 7 by the command to drill YHWH's word into the memory of the child by repetition, an activity which is largely intellectual. The command to love with the entire soul  emphasises the involvement of the entire human person, not simply the non-corporeal dimension but even the physical body, expressed by the binding of the tefllin (v. 8). Finally, the command to love with all one's force or strength

emphasises the involvement of the entire human person, not simply the non-corporeal dimension but even the physical body, expressed by the binding of the tefllin (v. 8). Finally, the command to love with all one's force or strength finds expression in bringing this knowledge to bear both in the domestic space, in the administration of all that the individual possesses, as well as in the public space, at the city gate, where matters of justice require even-handedness and integrity. The love of YHWH is divorced from neither domestic life nor the life of the wider society.

finds expression in bringing this knowledge to bear both in the domestic space, in the administration of all that the individual possesses, as well as in the public space, at the city gate, where matters of justice require even-handedness and integrity. The love of YHWH is divorced from neither domestic life nor the life of the wider society.

Transforming Education in Ghana: Shema as Paradigm

The above discussions on the biblical paradigm of education in Deuteronomy 6:4-9 suggest a three-point emphasis for the review of the education of the young in the contemporary Ghanaian context. These are the emphasis on an intellectual dimension, a holistic education, and an education for the common good.

Shema as Intellectual Education

The first is an emphasis on the intellectual dimension of education. The text of Deuteronomy 6:5b insists on the importance of the cognitive dimension with the use of the term 227. and subsequently in v. 7a with the verb  , which underlines repetition in the learning process. Importantly, the content of this intellectual dimension is the belief in YHWH alone as the God of Israel, a belief which itself was an intellectual innovation in the polytheistic context of the 7th Century BC. Israel's faith, as expressed in Deuteronomy 6:4, was a daring act of intellectual independence, which clearly defined the character of the nation and gave her an identity that would enable her to survive the impending national catastrophe.

, which underlines repetition in the learning process. Importantly, the content of this intellectual dimension is the belief in YHWH alone as the God of Israel, a belief which itself was an intellectual innovation in the polytheistic context of the 7th Century BC. Israel's faith, as expressed in Deuteronomy 6:4, was a daring act of intellectual independence, which clearly defined the character of the nation and gave her an identity that would enable her to survive the impending national catastrophe.

The push to relaunch Africa's development must necessarily reconsider the continent's intellectual formation of its young people. Okolie warns that the "intellectual and scientific dependency" on the West would only produce a "Western view of Africa's problems and the possible solutions for them" (Okolie, 2003:247). What countries like Ghana need are innovative, homegrown solutions to her challenges which can only be the fruit of an intellectual tradition that encourages free, courageous, and independent thinking.

Shema as Holistic Education

The second dimension of Shema instruction is the emphasis on holistic education. Israel is called upon to worship YHWH with her entire soul  . This involvement of the entire person receives further specification in the mention of the hand (

. This involvement of the entire person receives further specification in the mention of the hand ( , yād) and the eye (

, yād) and the eye ( , 'ayin) in v. 8. The child was thus to be instructed not just intellectually. According to Deuteronomy 6:8, the instruction was intended to have an effect on the entire corpus of the human person. YHWH's instruction was not just cognitive; it was targeted at the entire human person.

, 'ayin) in v. 8. The child was thus to be instructed not just intellectually. According to Deuteronomy 6:8, the instruction was intended to have an effect on the entire corpus of the human person. YHWH's instruction was not just cognitive; it was targeted at the entire human person.

The concept of what it means to receive a holistic education in Deuteronomy 6:8 challenges the tendency in many parts of Africa to overemphasise the cognitive dimension of education - reading, writing and arithmetic - at the expense of the acquisition of life skills. Essel et al. (2014:28-32), who blame this "contemptuous dichotomy" on the colonial legacy, decry the perception this has created in the wider society, which tends to view technical and vocational education as playing second fiddle to general academic education. The consequences of continuing in this trajectory are dire. With an unemployment rate in Ghana nearing 13.9% in 2022, and a freeze in public sector employment due to the impending IMF programme, the formation of a young population who possess the skills to create self-employment opportunities is clearly the preferred option (Ghana Statistical Service, 2002b).

The Shema as Education for the Common Good

Finally, the content of the instruction in Deuteronomy 6:5 stresses the dimension described as the strength or might  . This third dimension, as the ancient textual witnesses allude to, refers to that which the individual possesses. This, as I have argued, is re-echoed in v. 9 in the mention of the terms

. This third dimension, as the ancient textual witnesses allude to, refers to that which the individual possesses. This, as I have argued, is re-echoed in v. 9 in the mention of the terms (house) and the city gates

(house) and the city gates  The use of the term

The use of the term  itself includes the nuance of wealth, and even more importantly includes the members of the household (Josh. 24:15). Likewise, the mention of the city gates does not exclude the inhabitants of the city, and particularly the just relations which must exist among them (Dt. 21:19; Rt. 4:1-2).

itself includes the nuance of wealth, and even more importantly includes the members of the household (Josh. 24:15). Likewise, the mention of the city gates does not exclude the inhabitants of the city, and particularly the just relations which must exist among them (Dt. 21:19; Rt. 4:1-2).

The third dimension of the Shema's instruction is particularly critical for Africa's youthful population. With the continent acclaimed as the richest in natural resources, the challenge of contemporary Africa lies in using its wealth for the good of the entire society, for the entire household. With Sub-Saharan Africa still ranked the lowest in the world on the corruption perception index, Transparency International (2022) has warned that "grand corruption allows elites to act with impunity, siphoning money away from the continent and leaving the public with little in the way of rights or resources" (Transparency International, 2022). In Ghana, the Afrobarometer report, released by the Centre for Democratic Development (2022), indicates that large majorities of Ghanaians view government as being increasingly corrupt. Meanwhile, an unbridled desire for quick wealth, through illegal mining, otherwise known as galamsey, has led to the devastation of arable lands and waterbodies, in what has become Ghana's environmental nightmare and the greatest threat to sustainable development. What is clear is the failure of the current educational system to form young people with the right attitude to wealth, the respect for the common good, and the thirst for a just society. These are non-negotiable building blocks for transforming contemporary Ghanaian society and for the holistic development of the African continent.

Conclusion

African biblical scholars have long argued that the study of sacred scripture should not be divorced from the real existential concerns of contemporary society. The scriptures, after all, were themselves composed in response to real challenges with which the people of Israel were faced. The question of the education of the young, addressed in Deuteronomy 6:4-9, composed most probably in the national crisis of the 7th Century BC, thus teaches vital lessons for African nations struggling to shape their youthful population for the challenges of the 21st Century. Key to the teaching of the Shema are three dimensions of instruction: a focus on intellectual formation, on holistic formation and on the proper use of wealth or possessions. These three dimensions remain relevant for contemporary Ghanaian society. The country requires a redesign of its intellectual formation to align with the real needs of its people; it needs a realignment of the structure of education to refocus on skills development and to improve the problem of youth unemployment. Finally, Ghana needs urgent answers to the question of education for the common good, lest all its efforts at development are thwarted by the growing threat of corruption.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamo, D.T. 2015a. What is African Biblical Hermeneutics? Black Theology 13(1):59-72. DOI: 10.1179/1476994815Z.00000000047. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T. 2015. The task and distinctiveness of African Biblical Hermeneutic(s), Old Testament Essays 28(1):31-52. DOI: 10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n1a4. [ Links ]

Adu-Gyamfi, S., Donkoh, W.J. & Addo, A.A. 2016. Educational reforms in Ghana: Past and present, Journal of Education and Human Development 5(3):158-172. DOI: 10.15640/jehd.v5n3a17. [ Links ]

Amevenku, F.M. & Boaheng, I. 2022. Biblical exegesis in African context. Series in Philosophy of Religion. Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press. [ Links ]

Andor, J.B. & Quaye, E. 2014. Wholistic Adventist Education and the Shema Creed (Deuteronomy 6:4-9), Valley View University Journal of Theology 3:21-32. [ Links ]

Ayaga, A.M. 2015. Planning for church and state educational leaders' partnerships in Ghana: An examination of perceptions impacting relationships, Education Planning 22(3):37-62. [ Links ]

Ayuk, A.A. 2017. Teaching strategies for mission training from Deuteronomy 6:6-9, Journal of Asian Mission 18(2):85-99. [ Links ]

Badé, W.F. 1910. Der Monojahwismus Des Deuteronomiums, Zeitschrift Fur Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 30(2):81-90. [ Links ]

Birch, D.L. 1983. Home-centered Christian education, Christian Education Journal 3(2):30-38. [ Links ]

Bord, L.-J. & Hamidović, D. 2002. Écoute Israël (Deut. VI 4), Vetus Testamentum 52(1):13-29. [ Links ]

Bortei-Doku, E., Doh, D. & Andoh, P. 2011. From prejudice to prestige: Vocational education and training in Ghana. (Technical Report). London, UK: City & Guilds Centre for Skills Development. [ Links ]

Bruckner, J.K. 2005. A theological description of human wholeness in Deuteronomy 6, Ex auditu 21:1-19. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1985. Passion and perspective: Two dimensions of education in the Bible, Theology Today 42(2):172-180. [ Links ]

Chanimbe, T. & Dankwah, K.O. 2021. The 'new' Free Senior High School policy in Ghana: Emergent issues and challenges of implementation in Schools, Interchange 52(4):599-630. DOI: 0.1007/s10780-021-09440-6. [ Links ]

Cinnirella, F. & Streb, J. 2017. The role of human capital and innovation in economic development: Evidence from post-Malthusian Prussia Journal of Economic Growth 22(2):193-227. DOI: 10.1007/s10887-017-9141-3. [ Links ]

Craigie, P.C. 1976. The Book of Deuteronomy. (NICOT). Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Crouch, C.L. 2016. The making of Israel: Cultural diversity in the southern Levant and the formation of ethnic identity in Deuteronomy. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Available: https://brill.com/view/title/34069. [ Links ]

Derby, J. 1999. "...Upon the doorposts...", Jewish Bible Quarterly 27(1):40-44. [ Links ]

Driver, S.R. 1902. A critical and exegetical commentary on Deuteronomy. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. DOI: 10.5040/9781472555984. [ Links ]

Essel, O.Q., Agyarkoh, E., Sumaila, M.S. & Yankson, P.D. 2014. TVET Stigmatization in developing countries: Reality or fallacy, European Journal of Training and Development Studies 1(1):27-42. [ Links ]

Fabry, H.-J. 1995. ; לֵב ; lēḇלבֵָב ; lēḇāḇ. In Botterweck, G.J., Ringgren, H. & Fabry, H-J (eds), Theological dictionary of the Old Testament VII. Translated by Green, D.E. Grand Rapids, MI - Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans, 399-437. [ Links ]

Frevel, C. 2012. On instant scripture and proximal texts: Some insights into the sensual materiality of texts and their ritual roles in the Hebrew Bible and beyond, Postscripts 8(1-2):57-79. [ Links ]

Ghana Statistical Service. 2022. Ghana annual household income and expenditure survey. Highlight: 2022 First and Second Quarters Report of Food Insecurity, Multidimensional Poverty and Labour Statistics. Available at: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/AHIES%20executive%20summary%201%20(3 24PM).pdf. (Accessed: 2 January 2023). [ Links ]

Ghana Statistical Service. 2023. Ghana Fact Sheet. Available at: https://statsghana.gov.gh/ghfactsheet.php. (Accessed: 10 August 2023). [ Links ]

Grisanti, M.A. 2012. Deuteronomy. ePub Edition ed. (The Expositor's Bible Commentary). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Gylfason, T. 2001. Natural resources, education, and economic development, European Economic Review 45:847-859. [ Links ]

Herrmann, W. 2000. Jahwe und des Menschen Liebe zu ihm zu Dtn. VI 4. Vetus Testamentum 50(1):47-54. [ Links ]

Hoffner, H.A. 1975. ב , bayith. In Botterweck, G.J. & Ringgren, H. (eds), Theological dictionary of the Old Testament II. Translated by J. T. Willis. Grand Rapids, MI -Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans. 107-116. [ Links ]

Höffken, P. 1984. Eine Bemerkung Zum Religionsgeschichtlichen Hintergrund von Dtn 6,4, Biblische Zeitschrift 28(1):88-93. DOI: 10.30965/25890468-02801008. [ Links ]

Huebner, D. 1985. Religious metaphors in the language of education, Religious Education 80(3):460-472. [ Links ]

Isbell, C.D. 2003. Deuteronomy's definition of Jewish learning, Jewish Bible Quarterly 31(2):109-116. [ Links ]

Ismail, O.H. 2011. The failure of education in combating corruption in Sudan: The impact on sustainable development, OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development 2(11):43-50. [ Links ]

König, E. 1897. Historisch-comparative Syntax der hebräischen Sprache. Schlusstheil Lehrgebäudes des Hebräischen. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrisch'sche Buchhandlung. [ Links ]

Kraut, J. 2011. Deciphering the Shema: Staircase parallelism and the syntax of Deuteronomy 6:4, Vetus Testamentum 61(4):582-602. DOI:10.1163/15685331X560745. [ Links ]

Kruger, T. 2009. Das "Herz" in der alttestamentlichen Anthropologie. In Wagner, A. (ed.), Anthropologische Aufbrüche. Alttestamentliche und interdisziplinäre Zugänge zur historischen Anthropologie.(FRLANT no. 232). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

MacDonald, N. 2017. The date of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-5), Journal of Biblical Literature 136(4):765-782. DOI: 10.15699/jbl.1364.2017.196197. [ Links ]

Mbithi, P.M.F., Mbau, J.S., Nzioka, M.J., Inyega, H. & Kalai, J.M. 2021. Higher education and skills development in Africa: An analytical paper on the role of higher learning institutions on sustainable development, Journal of Sustainability, Environment and Peace 4(2):58-73. [ Links ]

Mbuvi, A.M. 2017. African biblical studies: An introduction to an emerging discipline, Currents in Biblical Research 15(2):149-178. DOI: 10.1177/1476993X16648813. [ Links ]

Mohammed, A.K. & Kuyini, A.B. 2020. An evaluation of the Free Senior High School policy in Ghana, Cambridge Journal of Education 1-30. DOI: 10.1080/0305764X.2020.1789066. [ Links ]

Moor, J.C.D. 1994. Poetic fragments in Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomistic history. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. 183-196. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004275775_014. [ Links ]

Nduku, E. & Makinda, H. 2014. Combating corruption in society: A challenge to higher education in Africa. In Nduku, E. and Tenamwenye, J. (eds), Corruption in Africa: A threat to justice and sustainable peace. (Globethics.net Focus no. 14). Geneva: Globethics.net International Secretariat, 281-302. [ Links ]

Nelson, R.D. 2004. Deuteronomy: A commentary. (The Old Testament Library). Louiseville, KY - London, UK: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Okolie, A.C. 2003. Producing knowledge for sustainable development in Africa: Implications for higher education, Higher Education 46(2):235-260. DOI: 10.1023/A:1024717729885. [ Links ]

Otto, E. 1999. Das Deuteronomium: Politische Theologie und Rechtsreform in Juda und Assyrien. (BZAW no. 284). Berlin - New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Otto, E. 2006. ש , ša ar. In Botterweck, G.J., Ringgren, H. and Fabry, H-J. (eds), Theological dictionary of the Old Testament. Translated by Green, D.E. Grand Rapids, MI - Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans, 359-405. [ Links ]

Parunak, H. V-D. 1983. Transitional techniques in the Bible, Journal of Biblical Literature 102(4):525-548. [ Links ]

Peter, M. 1980. Dtn 6, 4 - Ein Monotheistischer Text? Biblische Zeitschrift 24(2):252-262. DOI:10.1163/25890468-02402007. [ Links ]

Rabie, M. 2016. Meaning of development. in Rabie, M. (ed.), A theory of sustainable sociocultural and economic development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. 7-15. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-137-57952-2_2. [ Links ]

Rocca, C. & Schultes, I. 2020. Africa's youth: Action needed now to support the continent's greatest asset. Mo Ibrahim Foundation. Available at: https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/sites/default/files/2020-08/international-youth-day-research-brief.pdf. (Accessed: 2 January 2023). [ Links ]

Römer, T.C. 2004. Cult centralization in Deuteronomy 12: Between Deuteronomistic history and Pentateuch. In Otto, E. and Achenbach, R. (eds), Das Deuteronomium zwischen Pentateuch und Deuteronomistischen Geschichtswerk. (206). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 168-180. [ Links ]

Seebass, H. 1998. נפש nepeš. In Botterweck, G.J., Ringgren, H. and Fabry, H-J. (eds), Theological dictionary of the Old Testament IX. Translated by Green, D.E. Grand Rapids, MI - Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans, 497-519. [ Links ]

Seters, J.V. 1999. Introduction. In The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary. 1st ed. (T&T Clark Cornerstones). London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. 1-4. Available at: http://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/the-pentateuch-a-social-science-commentary/ch1-introduction/ [2017, January 27]. [ Links ]

Tigay, J.H. 1996. Deuteronomy: The traditional Hebrew text with the New JPS Translation/Commentary. (The JPS Torah Commentary). Philadelphia, PA - Jerusalem: The Jewish Publication Society. [ Links ]

Transparency International. 2021. Corruption Perception Index. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/press/2021-corruption-perceptions-index-press-release-regional-africa. (Accessed: 2 January 2023). [ Links ]

Ukpong, J.S. 1999. Developments in biblical interpretation in modern Africa, Missionalia 27(3):313-329. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J.S. 2000. Developments in biblical interpretation in Africa: Historical and hermeneutical directions, Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 108:3-18. [ Links ]

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022. Corruption in Ghana: People's experiences and views. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/corruption/Ghana/UN_ghana_report_v4.pdf. (Accessed: 2 January 2023). [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. & Breed, G. 2018. The role of parents in the development of faith from birth to seven years of age, HTS Theological Studies 74(2): 1-11. [ Links ]

Veijola, T. 1992a. Das Bekenntnis Israels: Beobachtungen zur Geschichte und Theologie von Dtn 6,4-9, Theologische Zeitschrift 48(3-4):369-381. [ Links ]

Veijola, T. 1992b. Höre Israel: Der Sinn und Hintergrund von Deuteronomium VI 4-9, Vetus testamentum 42(4):528-541. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, M. 2008. Deuteronomy 1-11: A new translation with introduction and commentary. V. 5. (Anchor Yale Bible). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Wolff, H. 1974. Anthropology of the Old Testament. Translated by Margaret Kohl. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

1 Targums refer to Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Scriptures. The Targum Onqelos is one such important translation of Babylonian origins. The Sifre Deuteronomium is a Jewish legal exegesis on the book of Deuteronomy while the Mishnah Berakhot is a tractate of the Mishnah and Talmud, that is, Jewish rabbinic commentaries on the Torah.