Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.121 no.1 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/121-1-2097

The Red Cow in Numbers 19: From Elimination Ritual to Sacrifice to Elimination Ritual

Esias E. Meyer

Department of Old Testament and Hebrew Scriptures University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

The red cow in Numbers 19 has perplexed scholars for quite some time. The paper engages with many of the questions they have raised, but especially with why this ritual is called a חטַָּאת and how the red cow ritual relates to the portrayal of the חטַָּאת in Leviticus. The paper explores the historical development of the חטַָּאת from a possible elimination ritual into two different sacrifices, and then into a ritual which produces a substance with apotropaic qualities. The last phase of this development took place in the late Persian period when the issue of pollution by corpses became more important.

Keywords: Red Cow; Numbers 19; Elimination ritual; Purification offering; Ritual innovation

Introduction

There is the older scholarly view that within Numbers 19 one still finds remnants of an ancient pagan ritual that was later reworked to become part of the Yahweh cult.1 Even a recent scholar such as Ruane (2013:147) is open to the possibility that the ritual depicted in Numbers 19 might have been "part of some goddess worship or other religious system." MacDonald (2012:352), on the other hand, is critical of scholars who think that the rituals of Numbers 19 "are primitive". His argument about the red cow is summed up as follows (2012:362):

In conclusion, we have shown that the red cow ritual is a literary creation, the result of an extension of rituals found in the developing priestly corpus and in the book of Deuteronomy. The anomalies in Numbers 19 arise not because we have an ancient ritual preserved in a late priestly form, but because we have a creative coordination of other rituals or ritual texts to create a new ritual.

When MacDonald refers to Deuteronomy, he is referring to the ritual in Deuteronomy 21:1-9, where a heifer's (עגְֶלהָ) neck is broken to absolve the community of the guilt of shedding innocent blood. His argument is that this ritual in Deuteronomy 21 influenced the authors of Numbers 19. MacDonald (2012:360-362) also shows how the חטַּאָת regulations of Leviticus 4-5 and the purity regulations of Leviticus 11-16 were appropriated in Numbers 19. Regarding Leviticus 11-16, he shows how ritual elements from Leviticus 11, 12, 14 and 16 are integrated into the newly created ritual prescribed in Numbers 19. I am going to present a similar argument, but with one difference, namely that I do think that we have "an ancient ritual preserved" here. However, it is not a pagan one, but rather an Israelite and even priestly ritual. The focus of this article will be more on Leviticus 4-5 and the חטַָּאת-sacrifice and how this sacrifice is reinvented in Numbers 19. I thus agree with MacDonald that we have a case of ritual innovation here, where old rituals are reinvented to meet the needs of new situations, but I present an alternative argument that an older ritual has indeed been reappropriated.2

The book of Numbers

Levine (2009:283) divides the book of Numbers into three parts:

Numbers 1:1-10:28 "Establishing a Holy Community"

Numbers 11:1-20:28 "In the Wilderness"

Numbers 21:1-36:13 "Conquest and Settlement of the Land"

Our text thus finds itself in the second part, towards its end, as the following overview also from Levine (2009:283) shows:

11:1-35, Complaints and challenges to Moses' leadership

12:1-15, Aaron and Miriam jealous of Moses

13:1-14:45, Reconnaissance and conflict over land

15:1-41, Ritual requirements

16:1-50, Rebellion of Korah, Dothan, and Abiram

17:1-12, Aaron's staff blooms

18:1-32, Qualifications for priests and Levites

19:1-22, Red heifer and water for impurity

20:1-13, Waters of Meribah and Miriam's death

20:14-21, Passage through Edom denied

20:22-28, Aaron's death

Most of chapters 11 to 20 are dominated by narratives, but embedded in the larger narrative are three chapters which could be described as more focused on ritual, namely chapters 15, 18 and 19. Chapter 15 has a casuistic character, often using the typical protasis/apodosis scheme of casuistic law, and will feature in the discussion below. Chapters 18 and 19 read differently, with the latter containing much more ritualistic material than the former.3 In the rest of this article, I will first focus on the ritual in Numbers 19, followed by an argument about the possible historical context of the text, before engaging with the debate on the חטַָּאת, including the possible development of the ritual over time.

The red cow of Numbers 19

Numbers 19 is divided into two parts by many scholars, namely verses 1-10, which describe the making of the "ritual detergent", and then verses 11-22, where the application of the substance is discussed (see Frevel 2012:202-203; Budd 1984:211; Berlejung 2009; Ruane 2013:109). Berlejung (2009:293) identifies three specific cases in the second half of the chapter (vv. 11-22), namely contact with a corpse, the death of a person in a tent, and contact with the dead during war. This paper will focus more on the first ten verses and thus the creation of the substance described as a "ritual detergent" to perform what some scholars would call an "apotropaic rite of riddance" (Monroe 2011:9), but which is certainly an "elimination ritual" (Ruane 2013:123). The most salient features of this creation of the ritual detergent are outlined next.

The Israelites are to bring a red cow with no blemish and on which no yoke has ever been placed (v. 2). This is the only time in the Hebrew Bible that the colour of a sacrificial animal is specified, with only one other example in the ANE.4 It is the only time in a priestly text where the sacrificial animal should not have been under the yoke (עֹֽל).5 The rather tautological description of both "without defect" (תּמִָים) and "there is no blemish" (מ֔וּם) also stands out. The former is typical of the way in which Leviticus describes an animal to be sacrificed,6 but the latter is found only in Leviticus 21 and 22, where priests with blemishes are disqualified from priestly service, and in Leviticus 24 where the noun blemish is used in the jus talionis.7 Eleazar (the son of Aaron) should take this cow and have it taken to the outside of the camp in order for it to be slaughtered there (v. 3). Unlike a sacrifice, the cow is not taken anywhere near the altar. Then Eleazar must take his finger and sprinkle some of the blood seven times in the direction of the front of the Tent of Meeting (v. 4).8 The use of the verb נזה (Hiph.) in verse 4 stands out. As Janowski (1982:224) has shown, this verb is used in P only for the חטַּאָת and the same goes for references to the use of the finger to execute this action of "sprinkling".9 For Janowski, נזה is a finer action that distributes less blood than in the case with the verb זרק(Qal), used for the manipulation of the blood of the חטַָּאת etc. The sevenfold repetition of the action is used for the חטַָּאת, but also for a few other rituals.10 This means that although the term has not been used yet, the description of the ritual already at the beginning of the text clearly uses terminology associated with the חטַָּאת.

The whole heifer is then burned outside the camp with cedar wood, hyssop and crimson added to the fire (vv. 5-6). These ingredients are also found in Leviticus 14, although they are not burned there. This process makes the priest unclean, and he now must wash his clothes and bathe himself before entering the camp, but he will remain unclean until the evening (v. 7). This cleansing ritual is similar to many described in Leviticus.11 The same ritual applies to the person who did the burning (v. 8). Then somebody else who is clean must gather the ashes and deposit them somewhere safe outside the camp (v. 9). The ashes will be kept in order to produce "water of נדִָּה֖" usually translated as "water for cleansing" (NRSV), or as we saw before with Levine "water for impurity". Verse 9 then concludes with: חטַָּא֥ת הִֽוא. "It is a chataat!" One could ask, what exactly is the referent of the pronoun? The consonantal text is masculine but pointed as feminine by the Masoretes. Thus Milgrom (1990:160) argues that if we read the pronoun as feminine, the referent is the cow, but if we take the masculine meaning, the referent is the ashes.

This is thus the first time that the word חטַָּאת is used, although, as we pointed out above, the terminology used in verse 4 already hinted at the fact that the text will be about a חטַָּאת, or put differently following the typical חטַָּא֥ת-like language of verse 4, the reference to the חטַָּא֥ת in verse 9 does not come as a surprise. Verse 10 concludes that the person who collected the ashes shall wash his clothes and remain unclean until evening. The fact that the process of creating ash, which is supposed to be used for ritual cleansing, later makes the people involved in the process unclean is the so-called "paradox" of this chapter. As Milgrom (1981:63) puts it:

Whereas the ashes of the Red Cow purify those whom they sprinkle, they defile those who do the sprinkling (vv. 19, 21) and, indeed, anyone who handles them (v. 21) and is involved in preparing them (vv. 6-10).

Verse 10b states that this "regulation" also applies to the stranger ( גֵּר ) in language reminiscent of the Holiness Legislation. The rest of the chapter goes into more detail about the three cases. The most striking element in the second half of the chapter is that priests do not play any role in the cleansing rituals performed on people who have been in contact with the dead. The term חטַָּאת (for sin or purification offering) is also used in the second part in verse 17, where the way of mixing the ritual detergent is specified (NRSV):

For the unclean they shall take some ashes of the burnt purification offering (dust of the burning of the חטַָּאת ), and running water shall be added in a vessel;

The word dust ( עָפָר ) is used now and not the word ashes ( אֵפ֣רֶ as in v. 9), but thus far the basic elements of the process that produces the "water for cleansing".

Scholars are perplexed by several aspects of this rite, especially when one compares Numbers 19 with texts in Leviticus where similar rituals are performed. Why is a female animal used? Why is the ritual called a חטַָּאת ? Is this text describing a sacrifice? Why are the ingredients used reminiscent of Leviticus 14? Why do priests play no role in the cleansing ritual performed with the ritual detergent? In responding to these questions, I will focus mainly on why this ritual is called a חטַָּאת , but I will also touch on some of the others.

Then there are the diachronic questions. Is Numbers 19 later than Leviticus and when should the text be dated? I will focus on these two questions first before venturing to address some of the others, especially on why what happens here is called a .חטַָּאת

Yet before we go there, we first need to engage with the question of what constitutes a sacrifice. Without a working definition or at least some basic criteria, it is impossible to answer whether what takes place here in Numbers 19 qualifies as a sacrifice. In an essay on Exodus 12, Gilders (2009:57-72) engages with the question of how to define a sacrifice.12 Concerning Exodus 12, he (2009:60-61) lists the criteria which he thinks constitute a sacrifice in P, but which are lacking in the ¡109 text:

1. There is no requirement for ritual purity;

2. There are no priestly officiants;

3. Animals are not slaughtered in a sacred space "before YHWH";

4. There is no altar, and no application of the blood to the altar;

5. No portion of the victim is burned as an offering to YHWH;

6. There is no reference to removing the fat for YHWH;

7. The meat is roasted and not boiled.

Regarding the first two criteria, the red cow ritual meets them. Ritual purity is clearly a requirement. Just in the first ten verses, we read of three people who have to perform cleansing rituals, even if only after performing a particular ritual. Yet verse 9 spells out that the person who collects the ashes should be clean before performing the ritual. We also have priestly officiants. Criterion 3 is not met in our text. The animal is slaughtered outside the camp, which is not a sacred space. With criterion 4, things are a bit murkier. There is no altar involved, but we have the application of blood by sprinkling it seven times in the direction of the Tent of Meeting. The same goes for number 5; we have burning, but this takes place outside the camp with the purpose of producing the ashes for the water of נדִָּה֖. The last two criteria are also not met, since everything is burned outside the camp, and nobody eats any part of the animal. Thus, in light of these criteria spelled out by Gilders, one should probably say that what takes place in Numbers 19 is not a sacrifice.

Historical context

With regard to the diachronic relation with Leviticus, I do not doubt that Numbers 19 draws from Leviticus and is thus the younger text. In this regard, I am following mostly European scholars such as Frevel (2013), Achenbach (2009), MacDonald (2012) and Kazen (2015).

Both Achenbach (2009) and Kazen (2015) argue that the problem of contamination by corpses only became an issue in the latest literary layers of the Pentateuch. Thus, in Leviticus 1-16 (or the older P part of Lev.), defilement by human corpses is not an issue. According to Leviticus 11 (vv. 24-40), the carcasses of unclean animals and the carcasses of clean animals that die naturally are unclean. Contact with them will require washing of clothes and waiting until the evening to become clean again. In the H part of Leviticus in 21:1-4, contact with human corpses becomes an issue for priests. They may only defile themselves with the bodies of close relatives. According to verses 10-12, the high priest may not come into contact with any corpse, including that of a close relative. These prohibitions probably explain why priests are not involved in applying the water of נ דּה֖ , since that would bring them into close contact with death. But to return to Leviticus 21, the point is that in Leviticus, dead bodies pose no threat to lay people. Achenbach (2009:360) continues:

Erst in Num 5,2-4 und 19,11-22 und damit in den jüngsten literarischen Schichten des Pentateuchs kommt diese Thematik in den Blick.

In Numbers 5:2, Moses is to command the Israelites "to put out of the camp every person with skin disease, every person with a discharge and every person who is unclean due to a corpse (NRSV)." As Frevel (2013:386-7) shows, it is difficult to understand this verse without assuming that Leviticus 13-15 is present in the background. Then in Numbers 5, the issue of contamination through contact with the dead for the ordinary Israelite is presented for the first time (in the canonical sense). Frevel (2013:401) argues that Numbers 5 "presumes not only Num 19 and a certain compositional form of the book of Numbers but also some form of Lev 11-15 and the Holiness Code alike." But even if Numbers 5 is later than Numbers 19, we can still presume that Numbers 19 draws from most of Leviticus.

Achenbach (2009:364-366) argues that the origins of this taboo around dead bodies could be the result of exposure to both Greek and Persian cultural practices in the late Persian period. Of these two cultures, the most extensive and systematic regulations around contact with dead bodies are found in the Zoroastrian religion of ancient Persia. For this reason, Kazen (2015:454-459) does not even engage with the possibilities of Greek influence, but rather offers a fairly detailed comparison between the purity regulations in Leviticus and Numbers and those in the Vendidād. But to make a long story short, I agree (mostly) with the following statement by Kazen (2015:455):

Considering the Holiness Code as somewhat later than the first half of Leviticus, but earlier than the latest sections of Numbers, we can detect an evolving process by which popular ideas of corpse impurity, including an apotropaic rite of burning a red cow and employing its ashes for purification by sprinkling, were domesticated by the Priestly authors and barely squeezed into their cultic system (Num 19).

For the reasons spelled out above, I thus read Numbers 19 as a very late Persian text in agreement with Kazen, Achenbach etc. I do not necessarily agree with the view that it was "barely squeezed into" the priestly cultic system. I also do not agree with "domesticated", which also presumes a pagan ritual modified to fit into the priestly system. I hope to show that the new ritual fits in quite nicely and that it is not a pagan ritual. In the rest of the paper, I will first engage with the issue of why this ritual is called a חטַָּאת and from that discussion, I will try to show how the priestly authors modified one of their own rituals to meet the challenges of new historical contexts.

About the חטַָּאת . A more synchronic perspective

I will not adopt the easy diachronic solution of regarding the references to the חטַָּאת as later additions. Thus Wefing (1981:354) regards the nominal sentence in verse 9 ( חטַּאָ֥ת הִֽוא ) as "völlig aus der Luft gegriffen" and thinks that it definitely forms a secondary layer. The very fact that verse 4 already used typical language usually associated with the חטַָּאת means that when this ritual was "designed" it was already clear that it will be some kind of חטַָּאת . I will try to argue that it was not grabbed out of thin air but taken from earlier priestly ideas.

From a canonical perspective, the חטַָּאת as a sacrifice appears in Leviticus 4 for the first time. One finds it again as a stand-alone sacrifice in Leviticus 6 and then later also in Numbers 15 and Numbers 19. This is not to mention many texts where the חטַָּאת is used in combination with other sacrifices, especially in cleansing rituals.13 Traditionally חטַָּאת was translated as "sin offering", which makes sense since the same word is used for sin. Apart from the fact that this means that the problem ( חטַָּאת ) and the solution ( חטַּאָת offering) go by the same Hebrew word, the most important challenge to the translation "sin offering" comes from Milgrom, who argues for "purification offering", a translation for which many scholars now settle, obviously with a few dissenting voices.14

Although the most extensive and systematic discussion of the חטַּאָת by Milgrom (1991:253-292) can be found in his 1991 commentary, his arguments go back much further and had already impacted on earlier commentaries of Leviticus.15 Milgrom (1971) was the first scholar to argue, in 1971 already, that the חטַָּאת sacrifice should be translated as "purification offering" instead of the more traditional "sin offering". For him (1991:253), it cannot be translated as "sin offering" because of texts such as Leviticus 12 and Numbers 6, where it is used to purify a woman who has given birth and at the completion of a Nazarite vow. Sin was not involved in either case.

Milgrom (1991:253) also put forward a grammatical argument, namely that the noun חטַָּאת is a derivative of the Piel stem formation of חטא and not the Qal. The Piel means "to cleanse, expurgate, decontaminate", with the Qal having the more traditional meaning of "to sin, do wrong".16 Therefore, translating the noun as "purification offering" would be more precise. Regarding the functioning of the sacrifice, Milgrom (1991:254-257) offers a clear argument, namely that the חטַָּאת purges the sanctuary and acts like a kind of ritual detergent. What is radical here, and what has elicited much criticism, is that it is not the offerer who is cleansed, but only the sanctuary.17 For Milgrom, the cleansing of the sanctuary is especially clear when blood is smeared on the horns of the altar (e.g. 8:15), in which case the blood then acts as a ritual detergent.

When Milgrom (1991:261-264) describes the actual performance of the חטַָּאת as found in the text of Leviticus, he identifies two kinds of this sacrifice. He sums up the difference as follows (1991:261):

They differ in that in one the blood is daubed on the outer, sacrificial altar and its meat becomes the perquisite of the officiating priest (4:30, 6:19), and in the other the blood is daubed on the inner, incense altar and sprinkled before the pārōket, but the animal, except for its suet, is burned on the ash heap outside the camp (4:6-7, 11-12).

For Milgrom (1991:263), the difference between the two lies in "degree" and not in "kind", by which he means that the burned חטַָּאת is the solution to deal with higher degrees of impurity. It absorbs stronger impurities and thus cannot be eaten, but (most of it) must be burned outside the camp in a neutral place, which is why it is called a "burned חטַָּאת". Examples of this kind of חטַָּאת are found in the first two cases of Leviticus 4, in verses 5-7 and 6-18, concerning the inadvertent sin of the high priest and the congregation. The blood of this sacrifice is sprinkled (Hiph. of נזה) on the curtain of the sanctuary,18 applied (Qal of נתן) to the horns of the inner altar and then poured out (Qal of שׁפך) on the base of the outer altar. Only the fat, the two kidneys and the appendage of the liver are burned on the outer altar. The rest, as we have said above, is burned outside. The sin committed here is the inadvertent sin of the high priest or the whole community and, for Milgrom (1991:257), these sins pollute the shrine and therefore the blood is applied to the curtain and the inner altar. The animals specified in these two cases are bulls. This is clearly the more potent חטַָּאת sacrifice.

We also have a sacrifice which Milgrom calls an "eaten" חטַָּאת , where the blood is daubed ( נתן ) on the outer altar and fat is burned on the outer altar. These sacrifices are found in the next three cases described in Leviticus 4. Thus, in verses 22-26, we read of a ruler who sins. Cases 4 (vv. 27-31) and 5 (vv. 32-35) refer to a person from the "people of the land" who sins inadvertently. In the case of a ruler sinning, a male goat is required and in the latter two cases, a female goat or a female lamb will do. Cases 4 and 5 are the first cases where female animals are required. Later, in Leviticus 6:19-22, we hear that the rest of the carcass shall be eaten by the priest who purified (Hitp. of חטא ), which is why this sacrifice is called the "eaten חטַָּאת ". Note that the verb נזה is absent in cases 3, 4 and 5. There is no finer sprinkling ( נזה ) going on, although it is always stipulated that the priest uses his finger (vv. 25, 30 and 34) when the blood is applied (Qal of נתן ) to the horns of the altar.

The verb נזה reappears again in Leviticus 5:9. The larger pericope (5:1-13) is still about the חטַָּאת , before the rest of the chapter focuses on the אשָָׁם . Verses 1-4 spell out different scenarios, including not testifying when you should, touching an unclean animal accidentally or similarly touching human uncleanness, or making a rash oath. Once again, a female goat or sheep will do, but in verse 7 the poor-man option of two pigeons or turtledoves is given. Verse 9 describes how the blood of one of the birds is sprinkled ( נזה ) on the side of the altar and the rest of the blood is poured out on the base of the altar.

Numbers 15:22-30 is also a fascinating text. It refers to two cases of inadvertent sin but provides far less detail about blood manipulation than Leviticus 4 and 5. In verses 22-26, we hear of the congregation sinning inadvertently, which is similar to Leviticus 4:6-18. Yet here more sacrifices are needed, including a bull as an עֹלהָ , along with a מִנחְהָ , a drink offering  and now a male goat as חטַָּאת . As in Numbers 19, there is also mention of the גּרִֵים , who will also be forgiven when these sacrifices are brought. It is not clear why more sacrifices are needed now for the same offence as in Leviticus 4, especially since a combination of sacrifices is used here that is usually used for cleansing from impurity and not sin. The second case of the individual is similar to Leviticus 4. Once again, the גֵּר is included in verse 29, and verse 30 spells out that there are no sacrifices for "high-handed" sin, which is presumably what this text wanted to add to Leviticus 4 (Budd 1984:174). About the חטַָּאת , in both of these cases, it is not clear whether we have a burned or eaten .חטַָּאת

and now a male goat as חטַָּאת . As in Numbers 19, there is also mention of the גּרִֵים , who will also be forgiven when these sacrifices are brought. It is not clear why more sacrifices are needed now for the same offence as in Leviticus 4, especially since a combination of sacrifices is used here that is usually used for cleansing from impurity and not sin. The second case of the individual is similar to Leviticus 4. Once again, the גֵּר is included in verse 29, and verse 30 spells out that there are no sacrifices for "high-handed" sin, which is presumably what this text wanted to add to Leviticus 4 (Budd 1984:174). About the חטַָּאת , in both of these cases, it is not clear whether we have a burned or eaten .חטַָּאת

But to return to Leviticus, it should be clear that in Leviticus 4 and 5 one has two kinds of חטַּאָת sacrifices, namely the burned חטַּאָת and the eaten חטַּאָת . The important question for us would be which one has the most in common with the ritual described in Numbers 19. One could argue that the חטַָּאת of Numbers 19 has four things (partially) in common with the burned חטַָּאת of Leviticus 4:

1) A bovine is involved but of a different gender;

2) Most of the burning takes place outside the camp, but the purpose of this burning is different in the two cases. In the case of the burned חטַָּאת it, it is simply to get rid of the carcass, but in the case of the red cow חטַָּאת, the purpose is to produce the ashes to be used in the cleansing ritual. Exactly what is burned also differs, since certain parts of the burned חטַָּאתis burned on the altar, which makes it a clear sacrifice;

3) In both cases, blood is sprinkled seven times, but the place where this is done differs. With the burned חטַָּאת the sprinkling takes place on the face of the curtain of the sanctuary, but with the red cow חטַָּאת, the blood is sprinkled towards the front of the tent of meeting. In Numbers 19, we thus have a kind of "remote" sprinkling;

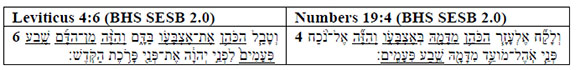

4) One could also add, as we have pointed out already, the use of the verb נזה, the specific mention of the finger and also the "seven times." Thus, the language used to describe the act of sprinkling has a lot in common with the burned חטַּאָת, as the following table shows with overlapping texts underlined:

Thus, the red cow חטַָּאת has much more in common with the burned חטַָּאת than with the eaten חטַָּאת . Only one similarity with the latter stands out, and that is the fact that with some of the eaten חטַָּאת -sacrifices a female animal is prescribed, including cases 4 and 5 from Leviticus 4 and the second case from Numbers 15 (even if unclear what kind of חטַָּאת it is in Num. 15). In all these cases, the animal is a goat or sheep rather than the bovine of Numbers 19. Yet the fact that a female animal was prescribed for certain kinds of eaten חטַָּ את -offerings means that the bovine female of Numbers 19 could have been inspired by these texts and not necessarily Deuteronomy 21, as MacDonald argues.

This distinction between burned and eaten חטַָּאת explained above by Milgrom is based solely on a synchronic description of the text, and Milgrom is not that keen on finding layers in a text.19 Other scholars have attempted to explain these differences by means of a more diachronic or traditio-historical explanation. Nihan (2007:179-186) is the most recent example of this kind of approach.

About the חטַָּאת . A more diachronic perspective

Nihan (2007:172-173) first observes that the חטַָּאת is used on four basic occasions which are also worthwhile taking note of:

1) In cases of inadvertent sin, as found in Leviticus 4:1-5:13 and Numbers 15:2239, as we discussed above;

2) On the occasion of the purification of an individual with the result of this individual being integrated into the community (Lev. 12, 14, 15 and Num. 19). In this category, Nihan thus includes Numbers 19, but what stands out here is that all the texts from Leviticus are cases of the combination of the חטַָּאת with other sacrifices, including at least the עֹלהָ , whereas in Numbers 19 the חטַָּאת is the only "sacrifice". Also, in Numbers 19, the חטַָּאת is used to produce the ash, which is later used in the actual purification of an individual;

3) When a person or an altar is consecrated (Ex. 29, Lev. 8, Num. 8) or when a person is reconsecrated (the Nazirite in Num. 6); and

4) In the context of regular ceremonies for the public and the cult (Lev. 16, Num. 28-29).

Nihan's (2007:179-186) diachronic reconstruction of the development of this sacrifice goes as follows and involves two historically distinct types of חטַָּאת:

First Nihan (2007:179) argues, building on observations by Rendtorff (1967:199234) and Janowski (1982:222-242), that originally there was a חטַָּאתwhich was not used in combination with other offerings, and the sole aim of which was to cleanse the sancta, as the following text shows:

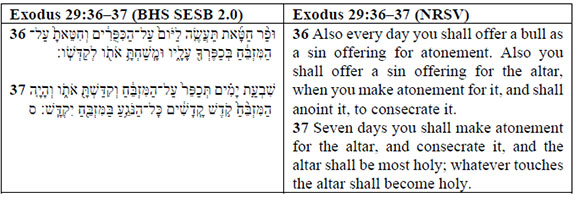

One should note that cleansing is done (Pi. of חטא) for the altar (עלַ־הַמִּזבְֵּ֔חַ) according to verse 36, and in the next verse, atonement is made (Pi. of כפר) for the altar (again ־ עַל הַמִּזבְֵּ֔חַ 20Yet if one were to take one further step back, then originally this ritual was probably not a sacrifice but an elimination ritual where the blood was applied to the altar of the sanctuary with the sole purpose of cleansing the altar and the sanctuary from impurities or eliminating impurities from them. Nihan also refers to texts from Ezekiel 40-48 (2007:179):

Furthermore, as some authors have pointed out, the testimony of Ez 40-48 clearly implies that this ritual was initially not an offering, but rather typically a rite of elimination, or of removal, of impurities attaching to the sancta. When the חטַּאָת serves for the cleansing of the altar or the sanctuary, it is never offered on the altar (see Ez 43:19-21, 22; 45:18-19, 20).

Thus when we say that originally the חטַָּאת was not a sacrifice or offering, we mean that none of it was burned on the altar as other sacrifices are burned. One could refer to Gilders's criteria, 5 and 6, discussed above. Nothing is burned on the altar and nothing is said of what happens to the fat. As we saw above, parts of the burned חטַָּאת are burned on the altar, even if the rest is burned outside. For Nihan, in this original cleansing ritual, the animal was simply burned outside to get rid of the carcass, but the actual cleansing took place with the application of blood to the altar. Remnants of this original ritual can still be seen in texts such as Ezekiel 43:19-21 and 45:18-20, where no part of the חטַָּ את is burned on the altar (Nihan 2007:179).

Nihan (2007:180) continues that it was P who developed this elimination ritual into a sacrifice proper. Now the suet had to be burned on the altar as with the זֶבַ֥ח שׁלְ מִָ֖ים (Lev. 3). The objective here was to integrate the חטַָּאת into the sacrificial system in Leviticus, and along with this change, the חטַָּאת was now also used for the cleansing of persons and not only sancta. Nihan (2007:180) puts it as follows:

However, a distinction is nevertheless maintained. Namely, contrary to what applies for the purification of sancta, where the חטַָּאת is sufficient (Ex 29:36-37; 30:10; Lev 8;15; 16:14-20a), the חטַָּאת in the case of the purification (or consecration) of a person is always associated with the offering of an עלָֹה֤ (as well as, possibly, other additional offerings).

Thus, for Nihan (2001:183-184) there is an older elimination ritual for the cleansing of sancta which comes from the second half of the First Temple period, but the authors of P developed this ritual into a proper offering at the beginning of the Second Temple period. This was originally a highly specialised ritual performed only by the priestly class. This sacrifice was later extended from applying only to sancta to being used for persons, although with the עלָֹה֤ (and sometimes other sacrifices) usually added. The objective of this offering was to cleanse sancta and people from impurity, not sin. This is thus Nihan's first type.

The second type (Nihan 2001:184) was an offering for moral sin committed by human beings, and in this case, it could be better translated as a "sin offering". Here the sacrifice is partly (including the fat) burned on the altar with the priest eating the rest. In Nihan's view, we thus historically had two distinct kinds of rituals, one being an elimination ritual aimed at cleansing the altar and one being a sin offering aimed at atoning for sin for an individual. For Nihan, we thus had two distinct types of offerings, not only a difference of degree, as Milgrom would have it. Yet Milgrom is interested in how these rituals function in the final text, while Nihan speculates how the two rituals might have developed over time.

In Nihan's (2001:186-198) discussion of Leviticus 4-5, he argues that the combination of these two historically distinct sacrifices into one system was the innovation brought about by the authors of these two chapters. For Nihan (2001:193), the Priestly authors did the following in Leviticus 4:

The problem raised by the combination of two different rites associated with each type of חטַָּאת was brilliantly resolved by the distinction, within the legislation of Lev 4, between two categories of inadvertent offenses (major and minor), involving in turn two distinct blood rites, one in which the victim's blood is used to cleanse the sanctuary whereas its remains are systematically burnt outside the camp (v. 3-21), the other in which the victim's blood only serves to cleanse the outer altar, while its remains need not be burnt outside and may presumably be eaten by the priest as is explicitly stated in Lev 6:19, 22.

When Nihan refers to "major and minor" offences, he is referring to what Milgrom would call "burned" and "eaten" חטַָּאת . But to sum up Nihan's argument, we initially had an elimination ritual and a sacrifice for sin. The former morphed into a sacrifice, with the added עֹלהָ used to cleanse human beings from impurity. The second one was a sacrifice for human beings who committed sins. The authors of P attempted to combine these two into one system and the very fact that we have in the final form of Leviticus 4 a burned חטַָּאת and an eaten חטַָּאת bears witness to the diverse traditions. Yet both are now used for sins, but in the description of the burned חטַָּאת , we still see remnants of the original elimination ritual. It is a bull, and most of the carcass is burned outside on the ash heap. It still has that element of the disposal of the carcass as Rendtorff imagined it with the original elimination offering. But let us return to the book of Numbers.

Why call what happens in Numbers 19 a חטַָּאת?

We have already shown that in Numbers 15 that the distinctions, which are clear in Leviticus 4, are absent. Yet the חטַָּאת is mentioned not only in Numbers 15 and 19 but in other texts in Numbers as well.21 Frevel (2013:376), after working through all these texts and at the same time accepting Nihan's argument about the "two types", comes to the following conclusion:

The evidence of the book of Numbers seems to corroborate the development and integration of the חטַָּאת in the Priestly offering system but does not provide clear evidence for two separate and distinct types of חטַָּאת of an inner diachrony. In most instances, the purifying aspect and the relatedness to the sanctum stand in the background. The 'two types' are not clearly differentiated, and although they are related to sin in some instances, they are largely free of moral aspects.

I think Frevel is mostly correct, especially in so far as there is no clear evidence of an "inner diachrony". We have already seen that one cannot distinguish between "burned" and "eaten" in Numbers 15. Yet what he does not see is that the process of preparing the ashes in Numbers 19 not only still has a lot in common with Milgrom's burned חטַָּאת but also with Nihan's earlier elimination ritual, which was not a sacrifice. How else could one explain the sprinkling in the direction of the Tent of Meeting except by arguing that there is some "relatedness to the sanctum" even if this relatedness is more remote? Thus Gilders (2006:13) puts it as follows:

The gesture of sprinkling places the red cow and the shrine into a relationship with one another. Furthermore, by prescribing that Eleazar sprinkle blood towards the Tent of Meeting, the text binds the red cow ritual to other rituals performed in and around the Tent of Meeting.

Rendtorff's understanding of an older ritual, where a bull was used to cleanse the sanctum and then the carcass was disposed of by burning, is also helpful. We have shown that the ritual for preparing the ashes has four similarities with the burned חטַָּאת , and some of these overlap with the way that Rendtorff understood the original elimination ritual, of which we still find remnants in Exodus 29 and Ezekiel 43 and 45. After discussing Ezekiel 43:19-26 and 45:18-20 Rendtorff (1967:206) concludes:

Offenbar haben wir es also bei den Weihe- und Reinigungsriten für den Tempel und die Altare mit einer genuinen Funktion der chattat zu tun.

For Rendtorff, the original (genuin) function of the חטַָּאת was that of a dedication and cleansing rite. In the description of the sacrifice in Ezekiel 43, it is a male bovine's blood that is applied to the altar, while the carcass is burned outside. In Numbers 19, it is a female bovine; blood is sprinkled in the direction of the Tent of Meeting and the carcass is burned outside. We thus have three basic similarities, namely a bovine, manipulation of blood and a carcass burned outside. Neither the ritual of Ezekiel 43 nor the one of Numbers 19 is a sacrifice, but both are elimination rituals, which adds a fourth similarity. To me, it seems clear that the ritual in Numbers 19 is not a manifestation of pre-Israelite thought but at most of pre-exilic priestly thinking (or pre-P priestly thinking) to which the text from Ezekiel also bears witness. The חטַָּאת in a sense went back to its roots. It started off as a non-sacrificial ritual for the elimination of impurity from sancta, and was then developed into a proper sacrifice by the authors of P in a rather elaborate system and was later reworked in Numbers 19 by a later generation of priests once again into a non-sacrificial elimination ritual.

For this very reason, I would argue that the authors of this chapter wanted to call this ritual a חטַָּאת from the start. Janowski (1982:224) has shown that the חטַָּאת and the Hiphil of נזה usually go together, which makes it strange that three pages later he (1982:227 n.211) would support arguments that the nominal sentence חטַָּא֥ת הִֽוא in Numbers 19:9 "ist deutlich sekundär eingesetz wurde". But this would mean that the verb נזה in verse 4 was also added later. To me, it makes more sense that the authors of this chapter thought that they would call this reinvented ritual a חטַָּא֥ת from the start. This becomes much clearer later when the action of sprinkling the concoction of ash and water on the tent and on the people who were exposed to the dead (vv. 18 and 19) is also expressed by means of the Hiphil of .נזה

Conclusion

Why is this ritual called a חטַָּאת ? Numbers 19 reappropriates an older חטַָּאת ritual which was not a sacrifice but an elimination ritual aimed at cleansing sancta. The reference to חטַָּאת is not a later addition, but the language used in verse 4 bears witness to the fact that the process of creating the ash was always going to be called a חטַָּאת . This reappropriation occurred in the late Persian period, when the issue of becoming unclean by means of exposure to dead bodies became a bigger issue, probably because of Persian influence. The חטַָּאת in Numbers 19 is thus not a sacrifice; it is also not a pagan ritual, but probably an ancient Israelite one, of which the memory still lingered in priestly circles.

Numbers 19:6 refers to the ingredients of "cedarwood, hyssop and crimson material", ingredients also found in Leviticus 14:6 during the first phase of the cleansing of a person who was healed of צרַָע֫תַ . This ritual also involves two birds, one of which is slaughtered while the other one eventually flies away. This ritual is usually regarded as very old and pre-P (Nihan 2007:274-275). In a discussion of this ritual, Eberhart (2011:30) reminds us that here too blood is sprinkled seven times on the person who needs to be cleansed. As part of this ritual, the live bird is released in an act that is clearly an elimination ritual. It is thus no coincidence that this older elimination ritual is also mixed into the new one of Numbers 19, but it supports the idea that what is prescribed in Numbers 19 is not a sacrifice but a cleansing and elimination ritual.

One question that I did not discuss in depth in this article is this: why a female bovine? I have mentioned that MacDonald thinks that Deuteronomy 21 played a role here. I pointed out that in cases 4 and 5 of Leviticus 4, which we discussed above, and in Numbers 15, a female animal is also prescribed. Thus, the idea of having a female animal as a חטַָּאת is not so strange, even if Leviticus 4 refers to a sacrifice and Numbers 19 to an elimination ritual.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Achenbach, R. 2009. Verunreinigung durch die Berührung Toter. In Berlejung, A. and Janowksi, B. (eds) Tod und Jenseits im alten Israel und in seiner Umwelt. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 347-359. [ Links ]

Baumgarten, A.I. 1993. The paradox of the red heifer. Vetus Testamentum 33(4): 442 451. [ Links ]

Berlejung, A. 2009. Variabilität und Konstanz eines Reinigungsrituals nach der Berührung eines Toten in Num 19 and Qumran. Theologische Zeitschrift 65(4): 289-331 [ Links ]

Budd, P.J. 1984. Numbers. Dallas: Word Books. (Word) [ Links ]

Clines, D.J.A. 1996. (ed) The dictionary of classical Hebrew. Vol. 3. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Eberhart, C.A. 2011. Sacrifice? Holy smokes! Reflections on cult terminology for understanding sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible. In Eberhart, C.A. (ed.), Ritual and metaphor. Sacrifice in the Bible. Atlanta: SBL, 17-32. [ Links ]

Frevel, C. 2012. Struggling with the vitality of corpses: Understanding the rationale of the ritual of Numbers 19. In Durand, J.-M.; Rõmer, T. and Hutzli, J. (eds), Les vivants et leurs morts. Actes du colloque organisé par le Collège de France, Paris, les 14-15 avril 2010. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg, 199-226. (OBO 257) [ Links ]

Frevel, C. 2013. Purity conceptions in the Book of Numbers in context. In Frevel, C. and Nihan, C. (eds), Purity and the forming of religious traditions in the ancient Mediterranean world and ancient Judaism. Leiden: Brill, 369-412. [ Links ]

Gane, R. 2005. Cult and character: Purification offerings, Day of Atonement, and theodicy. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Gilders, W.K. 2006. Why does Eleazar sprinkle the red cow blood? Making sense of a biblical ritual. The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 6: 1-16. https://jhsonline.org/index.php/jhs/article/view/5689 [ Links ]

Gilders, W.K. 2009. Sacrifice before Sinai and the priestly narrative. In Shectman, S. and Baden J.S. (eds), The strata of the priestly writings: Contemporary debate and future directions. Zurich: TVZ, 57-72. [ Links ]

Hartley, J.E. 1992. Word biblical commentary: Leviticus. Vol. 4: Leviticus. Dallas: Word Books. [ Links ]

Janowski, B. 1982. Sühne als Heilsgeschehen: Studien zur Sühnetheologie der Priesterschrift und zur Wurzel KPR im Alten Orient und im Alten Testament. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. [ Links ]

Kazen, T. 2015. Purity and Persia. In Gane, R.E. and A. Taggar-Cohen (eds.). Current issues in priestly and related literature. The legacy of Jacob Milgrom and beyond. Atlanta: SBL, 435-462. [ Links ]

Kamionkowski, S.T. 2018. Wisdom commentary: Leviticus. Vol. 3. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Levine, B.A. 2009. Numbers, Book Of. In Sakenfeld, K.D. (ed.), The new interpreter's dictionary of the Bible. Vol. 4. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 283-293. [ Links ]

Levine, B.A. 1993. Numbers 1-20. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. (Anchor Yale Bible). [ Links ]

MacDonald, N. 2012. The hermeneutics and genesis of the red cow ritual. Harvard Theological Review, 105(3): 351-371. [ Links ]

MacDonald, N. 2016. Strange fire before the Lord: Thinking about ritual innovation in the Hebrew Bible and early Judaism. In MacDonald, N. (ed.), Ritual innovation in the Hebrew Bible and early Judaism. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1-10. (BZAW 468) [ Links ]

Meyer, E.E. 2017. Ritual innovation in Numbers 18? Scriptura 116: 133-147. [ Links ]

Milgrom, J. 1971. Sin-offering or Purification-offering? Vetus Testamentum 21: 237-237. [ Links ]

Milgrom, J. 1981. The Paradox of the red cow (Num. XIX). Vetus Testamentum 31(1):62-72. [ Links ]

Milgrom, J. 1990. The JPD Torah commentary. Numbers New York: The Jewish Publication Society. [ Links ]

Milgrom, J. 1991. Leviticus 1-16: A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. (AB 3) [ Links ]

Monroe, L.A.S. 2011. Josiah's reform and the dynamics of defilement, Israelite rites of violence and the making of a biblical text. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Nihan, C. 2007. From Priestly Torah to Pentateuch. A study in the composition of the Book of Leviticus. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [ Links ]

Noth, M. 1968. Numbers: A commentary. Translated by J.D. Martin. Philadelphia: Westminster. (OTL) [ Links ]

Rendtorff, R. 1967. Studien zur Geschichte des Opfers im Alten Israel. Neukirchen- Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. [ Links ]

Ruane, N. 2013. Sacrifice and gender in biblical law. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Röhrig, M.J. 2021. Innerbiblische Auslegung und priesterliche Fortschreibungen in Lev 8-10. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. (FAT II/128) [ Links ]

Schmidt, L. 2004. Das 4. Buch Mose Numeri. Kapitel 10,11-36:13. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Seebass, H. 2003. Numeri 2. Teilband, Numeri 10:11-22:1. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. [ Links ]

Sklar, J. 2013. Tyndale Old Testament commentaries: Leviticus: An introduction and commentary Vol. 3. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [ Links ]

Watts, J.W. 2013. Leviticus 1-10. Leuven: Peeters. (HCOT) [ Links ]

Wefing, W. 1981. Beobachtungen zum Ritual mit der roten Kuh (Num 19:1-10a).Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 93:341-364. [ Links ]

Wenham, G.J. 1979. The Book of Leviticus. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

1 Especially Martin Noth (1968:141), who refers to the introduction of the priest as "a more advanced stage at which this material, to begin with of a quite actually magical character, has been brought into at least an outward connection with the legitimate (Yahweh) cult".

2 See also the other essays in the book edited by MacDonald, for which he wrote the introduction (2016:1-10).

3 Numbers 18 has much more of an economic ring to it, especially verses 8-32, which discuss the portions that are supposed to go to the priests and Levites. Still, there are a lot of references to offerings, and even if the focus of the chapter is the financial implications of the offering, one does find a more detailed discussion of rituals in the chapter. Verses 11-19 refer to the dashing of the blood of the 1133 sacrifice. See discussion in Meyer (2011).

4 See Baumgarten (1993:451) and the black bull of the Kalu priests.

5 I use "priestly text" in the very broad sense of the word. As we will see in the main text, Numbers 19 is most definitely not part of what was traditionally called P.

6 See Leviticus 1:3 and 10, where the עֹלהָ is described as such. Or, Leviticus 3:1:6, 9 where the זֶבַ֥ח שׁלְ מִָ֖ים also needs to be perfect. The same goes for the חטַָּאת and אשָָׁם֖ in Leviticus 4:3, 23, 28, 32, 5:15, 18, 25.

7 See Leviticus 21:11, 18, 21, 23, 22:20, 21 and 25. For the jus talionis, see Leviticus 24:19 and 20.

8 This article is not interested in what this act of sprinkling towards the Tent of Meeting means. As Gilders (2006:8-9) shows, the text does not explain this act to the reader. For Milgrom (1981:89) the act of sprinkling the blood is performed to sanctify the blood. For Levine (1993:462) the blood sprinkling is an attempt to purify or protect the sanctuary. Gilders (2006:13) tends to agree with Levine, although he argues for an "indexical" dimension to the text which binds this ritual "to other rituals performed in and around the Tent of Meeting."

9 Janowski (1982:224) still includes Numbers 19 in P, which is not a position most recent scholarship will agree with, as I will show in the next part.

10 In Leviticus 4:6, the priest performs the same action with the blood of חטַָּאת , but now sprinkles the blood seven times "before the Lord in front of the curtain of the sanctuary". The same happens in 4:17. In 16:14, Aaron takes some of the blood of the חטַָּאת bull and sprinkles it seven times "on the front of the mercy seat" and "before the mercy seat". The action in Leviticus 16 thus takes place behind the curtain. The sevenfold action is also used in Leviticus 8 and 14. In Leviticus 8:11, the "anointing oil" is sprinkled seven times on the altar. In Leviticus 14:7, during the first cleansing phase of the person healed from skin disease, the blood of the slain bird is also sprinkled seven times on the relevant person. In 14:16, oil is sprinkled seven times before the Lord as part of the third phase of the cleansing ritual in that chapter. The same happens in verse 27 as part of the "poor-man" option and in 14:51, where a house is sprinkled with the same mixture described in 14:16.

11 In Leviticus 14:8 and 9, after the ritual with two birds, the person who is to be cleansed should wash his clothes, bathe in water and shave his hair on day one and day eight. According to Leviticus 15:5-13, a person who has been in contact with a man with a "discharge from his member" must also wash himself and his clothes after seven days. Somebody who touches a woman who is menstruating (vv. 21 and 22) must do the same, or somebody who touches anything that was in contact with a woman with irregular blood flow (v. 21). In Leviticus 16:26, the one who took the goat for Azazel into the wilderness must do the same, or the one who burns the two חטַּאָת sacrifices shall do the same (verse 28). According to Leviticus 17, the person who has eaten something that has died naturally or was torn by wild animals will do the same.

12 See Ruane (2013:115-116) for a similar discussion, but specifically applied to the red cow ritual. She also presents a table where she contrasts a "sacrifice" with the "red cow rite" (2013:116). Unfortunately, she argues that a proper sacrifice always involves a male animal. As we will see below, this is not true since a female animal is sometimes prescribed for certain kinds of חטַָּאת sacrifices.

13 In Leviticus 12:6, the חטַָּאת is combined with an עֹלהָ for the woman who has just given birth and has completed the prerequisite waiting period. In Leviticus 14:23-32, the third phase of the person who was healed from skin disease is described. Apart from the חטַָּאת , an מִנחְהָ ,עֹלהָ and אשָָׁם are used. In Leviticus 15, we have a combination of the עֹלהָ and חטַָּאת , for the man who suffered from a discharge (vv. 13-15) and for the woman who suffers from an irregular discharge of blood (vv. 25-30). Leviticus 16 combines the עֹלהָ and .חטַָּאת

14 The most important example of such a dissenting voice would be James Watts. Watts (2013:307) prefers to stick to the term "sin offering" for חטַָּאת. His main argument against Milgrom is that when one translates the texts as Milgrom does, it loses the wordplay inherent in the Hebrew, a wordplay which must have had some rhetorical effect, according to Watts.

15 Wenham (1979:88-89) and Hartley (1992:55) are examples of older commentaries. More recent ones which still follow Milgrom include Sklar (2013:111) and Kamionkowski (2018:25).

16 See also Clines (1996:194-195), where the basic meaning of the Qal is to "sin, incur guilt" and for the Piel to "purify, cleanse from sin".

17 For criticism, see especially Gane (2005:106-143), or Nihan (2007:178-179). The most important point of critique that both Gane and Nihan agree on is that at times the חטַָּאת is actually used to cleanse the offerer and not only the sanctuary.

18 See Leviticus 4:6 and 17, where the object is indicated by the usual object marker.

19 Milgrom (1991:2-3) describes his own approach as "redaction criticism," but what he actually means by that is "synchronic rather than diachronic analysis." Although he acknowledges that the text developed over time, he would use source criticism only as a last resort.

20 For the most recent engagement with these verses, see Röhrig (2021:67-71). For her, verses 36-37 were added much later to the chapter, and her view is thus totally different from Rendtorff, who thought that we still see remnants of a much older ritual. In her (2021:251) diachronic overview, Exodus 29:36-37 should be understood on the same level as Leviticus 4-7* and certain verses from Leviticus 9. Her arguments do not contradict mine, since Exodus 29 is still much older than H and thus pre-dates Numbers 19. If she is correct, it actually means that the idea of the חטַָּאת as an elimination ritual and not sacrifice was still known in priestly circles at a much later date than older scholars thought, thus diachronically in closer proximity to Numbers 19. One aspect that is lacking in her book is a detailed understanding of the possible development of the חטַָּאת over time.

21 Frevel (2013:373) is especially interested in Numbers 6:11; 8:12; 28:22 and 29:5, as well as the verses from Numbers 15 we have just discussed.