Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.121 no.1 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/121-1-1795

ARTICLES

Convivencia Loading When People of the Way Read Authoritative Scriptures Together

Tsaurayi Kudakwashe Mapfeka

Department of Old and New Testament Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

This paper is a preliminary submission of the insights gained from the CIAS Conference (11-13 September 2019) pilot scriptural reading sessions. The empirical component of the CIAS postdoctoral research project includes observing and interacting with groups of active adherents of the three Abrahamic faiths, taking note of how people of faith appropriate meaning to their own authoritative scriptures and those of others. As a precursor to that exercise, a related protocol was rolled out at the event of the 2019 CIAS conference to pilot the exercise. This paper aims to offer a summative view of the notations from these sessions and to show how these are of value going forward. Three texts have been selected, one from each scriptural tradition of the three faiths, namely the Hebrew Bible, the Christian Bible, and the Qur 'an.

Keywords: Abrahamic faiths; Africa; Egypt; Diaspora; thematic topos

Introduction

This is a paper developed as a preliminary submission of the insights gained from the Centre for the Interpretation of Authoritative Scriptures (CIAS) Conference (September 2019) pilot scriptural reading sessions. The empirical component of the CIAS postdoctoral project includes observing and interacting with groups of active adherents of the three Abrahamic faiths, taking note of how people of faith appropriate meaning to their own authoritative scriptures and those of others. As a precursor to that exercise, a related protocol was rolled out at the event of the 2019 CIAS conference to pilot the exercise. This paper aims to offer a summative view of the notations from these sessions and to show how these are of value going forward. I must state that this paper is not a minute-by-minute capture of the reading sessions but a summative rendition intentionally organising material to suit a desired thematic flow.1 Three texts have been selected, one from each scriptural tradition of the three faiths, namely the Hebrew Bible, the Christian Bible, and the Qur'an. Respectively, the texts are Genesis 12:10-20, Matthew 2:13-23 and Qur'an 10:75-92. These texts were chosen because, prima facie, they read as foundational in their respective traditions, saying something about identity formation of the respective religions; mention Egypt, and include some migration element - collectively forming a thematic topos for the overall project.

Outcomes of the Readings

CIAS Conference 2019 programme provided for three sessions (one per day), each lasting about one and half hours, in which selected colleagues working with one of the three mentioned scriptural traditions would offer reflections on the selected texts. The floor would then be opened to the whole conference for participants to offer their own thoughts and/or ask questions. As noted in the introduction above, the following is a summative rendition of the outcomes of these reading sessions.

The Hebrew Bible: Genesis 12:10-20

Preliminary remarks were from three Hebrew Bible scholars, and while one was Jewish and the other two Christian, they were all clear in that their remarks were based on their exegetical convictions. This seems to have set the tone for all subsequent readings as will be shown below. In part two of this paper below, I will offer a preliminary analysis of the methodological strategies at play in the pilot reading sessions, which will be the basis for data codification for the project. Confessional readings were intentionally set aside with preference given to more academically nuanced readings.

At a historical-critical level, Genesis 12:10-20 presents a problem in that the same motif of presenting a wife as a sister, of course with different narrative contexts and characters, is repeated in Genesis 20 and 26. In the end, there are three narratives in close textual proximity with none showing narrative awareness of the existence of the other two. This is a detail that has attracted the attention of many biblical scholars.2 It is in his discussion of the Pentateuch as a whole that John Barton (1996:22) remarks:

A work which consists of narrative mixed with poems and hymns and laws, which contain two or even three versions of the same story set down with no apparent awareness that they are the same, and which changes style so drastically from paragraph to paragraph and from verse to verse, cannot in a certain sense be read at all: you simply don't know what to do with it.

There seems to be a general consensus that it is a detail that could be used to argue that in this text we are dealing with a literary figure as opposed to a historical one. In any case, it is only a few scholars who would utilise details of a tradition such as this for historical constructions, as the futility of such an endeavour has long been persuasively stated as far back as the nineteenth century, when Julius Welhausen (1885:360) noted:

It involves no contradiction that, in comparing the versions of the tradition, we should decline the historical standard in the case of the legend of the origins of mankind and of the legend of the patriarchs ... the patriarchal legend has no connection whatever with the times of the patriarchs.

It makes sense to locate this narrative in the period when the Levant was the most obvious route if not the site of many battles pitting Egypt to the south and Mesopotamian Empires to the north, most probably in the period leading up to and including the first quarter of the first millennium BCE. Thomas Römer (2018:63) is of the opinion that 'the geographical "map" in Genesis can be shown to retain the memory of Egyptian domination over Canaan during the second millennium BCE.' It would not be unusual then for biblical Israel to view Egypt as an enigma, thus making literary imaginations including things Egyptian commonplace. In a world dominated by these superpowers, biblical Israel, armed with a belief in the providence of an all-powerful deity, needed to create its own space. The narrative became one in which identity was negotiated and formed.

One cautious remark emphasised the need to read this text first in its broader literary context before applying it to other concerns. It was suggested that the textual limits should be set as Genesis 12:1 to 13:18, where the Lord makes two promises: first, that land would be given to Abraham and, second, that the same land is also promised to his seed. The narrative includes two corresponding problems that seem to test and at the same time clarify the promises. First, having obeyed the call to leave his place of origin in the Mesopotamian region and now trying to settle in the promised land, Abraham is faced with a disastrous famine that makes another flight inevitable. Second, having arrived in Egypt seeking refuge from the famine, he finds himself at the verge of losing his wife to his host. These two problems would mean an end to both promises. In rescuing Sarah from the Pharaoh's bed, the Lord kept alive the promise of a seed to Abraham, who would be heir to the Promised Land. However, there is still one more lingering problem that the Lord must resolve. The covenant the Lord made to Abraham and his progeny is exclusive. Yet on leaving Mesopotamia, Abraham had brought along Lot, his brother's son, which poses the challenge of defining in clear terms whether the nephew was included in the promise. Genesis 13:14-18 clarifies the matter as Lot is separated from Abraham; the promise is to Abraham alone and only to Abraham's seed.

The other element that featured in the reading session with considerable emphasis is that of migration. In one particular contribution, it was noted that the trauma necessitated by famine made the sojourners particularly vulnerable. Contrary to the Xhosa (seen as representing 'African') philosophy as expressed in vernacular proverbs and idioms, the text cast Egypt as a very hostile migration destination. The horror of diaspora is always worse for women, and the narrative's rendering of Sarah's experience confirms this fact.3It is on this backdrop that the text is particularly relevant in the current context in South Africa, where xenophobia and gender-based violence are matters of serious concern hogging the limelight in current affairs and most social media platforms.

The Christian Bible: Matthew 2:13-23

A reading of this particular text must attend to questions of textual delineation and attend to the question: 'what is the birth narrative doing in relation to the rest of the story of Jesus as preserved in the gospels?' When all the four canonical gospels are read side by side, it becomes clear that the birth narratives in Matthew and Luke are later additions to the original story of Jesus, which starts with baptism by John the Baptist as preserved in the Gospels of Mark and John. Matthew and Luke seem to have worked from the understanding that for a prominent person like Jesus, some narrative of his origins is necessary in order to show that he was Lord from birth (as opposed to the son of a carpenter turned into a maverick rabbi of sorts at a later point in life). To this end, both Matthew and Luke have access to various sources about this prominent figure which the gospel writers used each in their own way, of course Luke with a more romanticised version. Apart from making deliberate connections with the story of the biblical Jews by making a case of similarities between Jesus and Moses as will be fleshed out below, it also was a view openly held from time immemorial that the great figures to grace the human historical plane were so destined before their birth. For instance, Herodotus (1:107-130) recounts some of the legendary material (upon which he expresses serious doubts) regarding the birth narratives of Cyrus the Great.4 It appears to be a literary type that continued into New Testament times and for some time into the Common Era. It is for the same reason that dubious or at least questionable genealogies were crafted and attached to names of prominent figures.5 In a recent publication, I have discussed how the naming of Ruth's son reads awkwardly as a conscription (and corruption) of an otherwise independent tradition with the intention to provide colour to David's otherwise unimpressive, or worse, unknown genealogy (Mapfeka, 2019:87).

Reference to Jesus' connection with lowly Nazareth could have accounted for some element of scorn, as exemplified in John 1:43-46. Commenting on the disputed idea that Jesus was somehow a part of the Essenes, George J Brooke makes the following comparative remark:

On the one hand the key characteristics of Qumran Essenism are priestly purity, a determined protection of sacred space, hard-line legal interpretation, all produced by a group which is the product of the urban élite, principally from Jerusalem. On the other hand, Jesus is from a lower-middle-class family whose ministry shows him to have an affinity with country folk. His table fellowship is open and notably scandalous (Brooke, 2000:23-24).

In other words, being from Nazareth in a world where social and geographical locations were almost synonymous and translated into Jesus being of low stock. On the contrary, by the time of Jesus and despite the Levant changing hands among several imperial authorities, Egypt remained a towering civilisation with a long history of demonstrated prowess and dominance stretching over several centuries. I have already stated above that as far back as the eighth century BCE, Egypt was already a well-established civilisation with advanced systems of knowledge and political administration. To this end, Walter Brueggemann (1989:160) avers: 'The Egyptian Empire, old and stable, was indeed a centre of vast learning.' It must have counted for some prestige to be associated with Egypt, which by the turn of the millennium must have had quite some positive aura in the Levant area. Retrospectively adding the great Egypt to Jesus' birth narrative accomplished two things, including addressing the 'unfortunate' detail of being a Nazarene. First, it associated Jesus and Egypt, one of the oldest civilisations known to humanity, thus countering the negativity associated with coming from Nazareth. Second, as Edwin D. Freed (2001:101) notes, it fulfilled the prophecy: 'Out of Egypt I called my son' (Hosea 11:1).

Since Matthew is renowned for his focus on making the story of Jesus make sense to a Jewish audience, it would not be far-fetched to theorise on the possibility of a deliberate effort at drawing parallels between Jesus on the one hand and on the other the patriarchal traditions, Moses and the whole Egyptian excursion. In relation to the narrative of the flight to and return from Egypt, Freed (2001:101) is not hesitant to declare: 'Herod and Jesus are symbolic of Pharaoh and Moses in Exodus ...' The Exodus tradition recounts how the birth of Moses and his survival was a matter of contravening a political decree by the Pharaoh instructing all midwives to ensure that all male Israelite children are killed at birth (Exodus 1:15-22). In a similar manner, the selected text recounts how the court of the political authorities of the land became aware of the birth of Jesus, triggering a widespread infanticide, hoping to eliminate the unknown legendary child. It would seem like this text is not intended to convey a historical detail but is rather a literary type aimed at presenting Jesus as the new (and better) Moses.

Bearing in mind the fact that the work of the gospel writers came to life decades after the death of Jesus and decades more after his birth, it seems that the past was being reshaped to address problems associated with what were current challenges. It is a time when Christians had been chased out of the synagogues and Christianity had become a stand-alone religious community distinct from Judaism. Matthew must have been keen to encourage the new community by, among other things, drawing on the formative traditions of biblical Israel, as if to say; 'take heart, Jesus is Moses recast, we are the new Israel.' Like the Hebrew Bible text discussed above, the narrative here is an integral part of the new religion's identity negotiation process. Brooke (2000:25) recalls a reception history tradition insinuating that the kind of royalty Jesus represented would be the same as if not greater than that of Egypt and Assyria. It would make sense then to present Jesus as somewhat hailing from not just lowly Nazareth but also with links to the mighty Egypt.

At this point, it is worth mentioning the obvious, the fact that historiography has morphed considerably since the gospels were written. The line separating writing history and writing fiction in antiquity and beyond was evidently blurred. Fiction was firmly anchored in history and historical material was freely interspaced with fictitious material. At the time of Jesus' birth, Herod the Great, who died in 4 BCE, ruled Judea. This detail provides for some difficult reading in that if it is this Herod from whom Joseph and Mary had to take a flight to Egypt, Jesus must have been born in or before 4 BCE. It would entail some mental calibration to say that Christ was born some four years (or more) before Christ (BC).

Israel to Egypt is a distance of upwards of 350 miles in a straight line - about a week's journey on foot - but presumably more for this particular couple given that it was within the first week of the birth of their baby. There is sufficient evidence that there was a large Jewish population in Egypt at this particular time; an estimated 30% of the Mediterranean population in Egypt at this time was Jewish, with a huge presence in places such as Alexandria. It is also known that around this time, Jewish communities in Egypt were allowed to live in peace, even enjoying the privilege of tax exemption. While the charge that the selected text and the broader literary unit of pre-baptism narratives are a result of creative imagination on the part of Matthew, Luke and/or their sources, the historical reality at the turn of the first millennium CE provides for the possibility that some details could have some historical credence.

Additionally, it is important to emphasise that the foregoing positive image of Egypt read as informing Matthew's choice of material and adding to the story of Jesus, most certainly drawing from Hebrew Bible traditions, was not constantly maintained. Depending on the point in the timeline of the memory of biblical Jews and the theological interests of the authors, on the whole, the Hebrew Bible reflects a love-and-hate attitude towards the institution of the Pharaoh, the land of Egypt, and all things Egyptian. On numerous occasions, the land of Egypt is a favoured destination for refuge and food supplies. The same is equally conspicuous as a place of servitude and suffering. Matthew's rendition here is most definitely along the lines of a positive image. Engaging the text with the intention to establish its historical veracity will not yield much. Rather, for our purposes here, the question goes beyond the history/fiction dichotomy to include consideration of what the author is doing with the material. To this end, it seems that Matthew's primary purpose is to encourage the emerging Jewish Christian community that in this Jesus, YHWH the God of the fathers had set out to bring to fruition the salvific mission that started with Moses.

The Qur'an: 10:75-92

In Islamic tradition, there is no confusion regarding the distinction between Egypt (especially the figure of Pharaoh) and the rest of Africa. Pharaoh is the epitome of tyranny, oppression, arrogance, corruption, genocide, etc. Muslims are known to pronounce curses each time the name of Pharaoh is mentioned. Islamic tradition retains a memory of a vivid conversation between Prophet Muhammad and the angel Gabriel in which reference is made to the angel's efforts to silence the Pharaoh by keeping his mouth full to stop him from confessing to Allah, for he was the son of Satan the angel hated most. The cited passage follows the same template where the Egyptian Pharaoh is the arrogant and cruel ruler who, even in the face of every reasonable argument, still resists submitting to the way. However, in the end and at that moment when his army, horses and chariots drown before his very own eyes while pursuing the children of Israel, he confesses: 'I believe that there is no other god but He in whom the children of Israel believe, and I am of those who submit.' (10:90). Emphasis is placed in the fact that Israelites are viewed positively as those who submit to the one God Allah (thus Muslims). It is worth mentioning that in the cited passage, the Qur'an rendering has Moses addressing the Israelites as Muslims on at least two instances. It is held in one Islamic tradition that to this day, Muslims hold as holy the 10th day of September commemorating Moses' victory over the Pharaoh. It is clear from the foregoing that in the Qur'an, Jews and Christians, who are referred to as 'the people of the book', are perceived in a positive light on account of a shared belief in one God. In any case, Prophet Muhammad did not claim to start a new religion:

... Muhammad made it clear that his was not a new message but the true message in pristine version that had once been given to Jews and Christians. The message of God to Moses, Jesus and Muhammad was one, the very same message given to Abraham, who, the Qur'an notes, was neither Jew nor Christian. (Heck, 2009:45)

It makes sense then that Jews and Christians, both known in the Qur'an as dhimmi (the subservient people) enjoyed several privileges protected under the Pact of Umar which was established around 800 CE in Muslim-controlled territories.6 Despite theological differences, Islam is built around the understanding that the Prophet Mohammed presented the final revelation of the same one message of the same one true God whose salvific efforts were recounted in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. It goes without saying then that the attitudes of Islam to Egypt and diaspora are already embedded in the continuous religious template of which Islam as a faith is only a sequel.

Having noted the similarities, the reading session brought to bare several differences and distinctions. For instance, the Hebrew Bible exodus story, while referred to in the Qur'an, is not the main liberation story as Muslims have their own liberation story centring on Muslims returning to Mecca. Universal application of the term Muslim to include Abraham, his seed, and all the prophets on the account of their belief in and confession of the one true God leaves Jews and Christians short in that they would not have taken the confessional oath stating the oneness of God and that Mohammed was indeed the last prophet of that one God.

In the end, it was suggested that for the purpose of this exercise, a more foundational portion of the Qur'an should be used to which it was agreed that discussions with colleagues within the network would continue to find additional or alternative textual portions in the Qur'an.

Consideration of Interpretive Codes

In this section, I wish to analyse how the opening of the biblical (and Qur'anic?) interpretation has necessitated reconfiguration of interpretive codes for authoritative scriptures and the manifestation of these codes in the reading sessions under discussion. It is well known that the entities here referred to as 'authoritative scriptures', claims of divine authorship notwithstanding, have been mediated through human languages. The processes of canonisation for the religious texts of the three faiths have human personages at the centre; determining the nature, content and definition of scripture and appropriating the same with meaning and authority. Where it concerns the Hebrew Bible and utilising discussions in the Jewish Rabbinic traditions, Barton (1986:68-72) notes that arguments relating to which biblical texts did not defile hands, such as Esther, were not about their sanctity but rather about the fact that they were narratives meant to be recited and not read. While Barton's notation may be contestable, what is indisputable is the fact that defining scripture and its holiness are matters locatable in the hands of human beings. In a recent Masters thesis under the CIAS banner, Paul Adebayo has explored the meaning-boundaries of scripture with particular focus on canonicity and authority:

This study ... investigates the concept of Christian Scripture in 2 Timothy 3:14-17 as it seeks to understand the relationship between the usage of the Greek terms ιερά γράμματα, γραφή, and θεόπνευστος and their implications on the concept of scripture judging from the selected pericope. This study further seeks to observe how these words and the text in question have contributed to an understanding of scripture especially as it relates to the debates on its inspiration and authority (Adebayo, 2019: Stellenbosch).

Understandably, for the longest of time, the authoritative scriptures have remained the property of the respective faith traditions. However, as the authority of these texts spilled beyond the confines of the religious spaces that owned them to influence epistemology, politics, economics, and social order; it became imperative that these authoritative scriptures should make some sense in a correspondingly wider context. I will now turn to look at the broad codes by which authoritative scriptures have been read and that I saw at play in the reading sessions.

The Text

As already noted above, adherents of the three Abrahamic faiths are also known as 'people of the book', for they are known as people whose faith is regulated on the basis of scriptural traditions fixed in written forms. The Christian tradition today includes the memory of a movement that posed serious challenges to the very core of its existence; the Reformation in which the cry for sola scriptura became more than a mere mantra but a clarion call, necessitating a redefinition of the church's understanding of scripture and its authority (Mapfeka, 2019:25). Human language limitations, errors in transmission, deliberate editorial or redaction mutilations, and translational shortcomings are only a few among a plethora of factors making the claim of scriptural infallibility unsustainable. The reading sessions devoted time to working through problems related to the text itself and textual authority. For example, during the Christian Bible reading session, one of the major talking points was about how to read the selected text if it can be proven that the whole birth narrative gamut was only a later addition to the original story of Jesus.

The World of the Text

It was not long before it became apparent that textual imperfections were only part of the problems that made reading authoritative scriptures so complicated. Jonker (2015:139) puts it aptly when he says, 'Each text in the Bible originates from somewhere/someone.' Each text has a history. It is only axiomatic now to state that for more than one and half centuries, the biblical hermeneutic enterprise has thrived on the use of historical criticism. It is an approach that Fernando Segovia (2000:147) has described as 'the much-beloved scientific method that held sway in academic circles from the early nineteenth century to the third quarter of the twentieth.' Segovia's timeline makes sense in that from the last quarter of the twentieth century to date, biblical studies has witnessed the meteoric rise of approaches from the margins. However, while this development means that historical criticism has become one of many alternative approaches to biblical interpretation, it is my opinion that its gains are indelible, and its primacy remains intact. In all its variations, historical criticism was built around the understanding that the text was an 'intelligible' entity, sui generis, and available to be 'interrogated' by use of the right method. "Who wrote a given text", "to whom", "why", "what was going on in the broader context", "what genre was used" ... the list of questions is almost endless. In this understanding, it would not matter who was reading the text; by using the right method, anyone anywhere would reach the same conclusions. It was held that meaning was in the text, and the responsibility of the exegete, like that of a professional miner, was to use the right methods and tools to dig through the text and find that meaning. In this regard and despite the heat the historical critical approach(es) generated, preoccupation with 'the text' remained the primary focus.

The World Beneath the Text

A 'perfect text' and an established historical context would help reading a text but would not suffice. The biblical hermeneutic enterprise has found itself having to face yet another frontier in the ideological or rhetorical interests behind the text. Limiting the authoritative scriptural enquiries to questions of text and history gave rise to the assumption that scriptural narratives could be of real value in understanding the past. By using material in scripture like genealogies, proposals have been made in dating major events like creation, the deluge, the exodus, the conquest of the land of Canaan, the institution of the monarchy, the birth (death and ministry) of Jesus, the call of Prophet Muhammad, and so on. In recent years, discussions in biblical studies have seen heated debates, with some scholars not only expressing doubts on the value of scripture in historical constructions but also condemning it as a hindrance to that effort. The problem peaked to crisis proportions in Philip Davies' (1992) publication entitled In Search of "Ancient Israel", metaphorically speaking as questions raised here pulled asunder the concept of ancient Israel hitherto assumed to be an established fact. Davies (1992:16) argues that 'ancient Israel' is a scholarly construct and not the same as the Israel of biblical literature. This is a position that has found support and has been developed further in the works of modern-day big names in the field of Biblical Studies such as Thomas L. Thompson, Keith W. Whitelam, and Niels Peter Lemche, to name a few. 'Minimalists' and 'maximalists' are terms that have been thrown around derogatively to describe scholars who see little value in the Bible in historical construction on the one hand and, on the other, those who see more value in this respect. Writing ten years after Davies, V. Phillip Long (2002:1) expresses the consequent crisis:

It is not uncommon nowadays to hear that biblical studies in general, and OT studies in particular, are in a state of crisis. Old consensus positions have been abandoned, and questions formerly thought to be answered are again open for debate.

The value of the authoritative scriptures in historical construction has become a matter that must be proven rather than assumed. That becomes the core of the methodological challenge for this project. Carol Meyers (2002:67), commenting on the process of history-writing, notes:

It has also been made clear that biblical sources from which we might attempt to write history were never intended to be eyewitness accounts or even general summaries of events. Rather are highly selective and imaginatively expanded accounts of the meaning and nature of past times. That is, the texts themselves have strong ideological biases that distort or mask events and characters.

Scriptural texts were written to advance certain ideological or rhetorical interests and not to recount historical events. Contributions in the CIAS Conference reading sessions included attention to ideological and rhetorical interests latent in the texts selected for the reading sessions.

Reader Response

All the foregoing considered, fixation on the text has now relaxed to include considerations of the interactive space where the reader meets the text. The reader brings the person they are (their identity), and what they make of a text is closely related to their own identity and make up. Claims to objectivity notwithstanding, even the most 'scientific' methodologies in authoritative scriptural hermeneutics are replete with the biases of their proponents. As an example, in German biblical scholarship from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the much-celebrated historical constructions of the world of biblical Israel that saw this ancient state emerging from a context of conflict and wars came around during the establishment of Germany as a state. It is clear that the positions taken are not the results of diligent scrutiny of the texts necessarily and exclusively but include elements of the world of the reader. It matters whether one is a man or a woman, black or white, rich or poor, straight or homosexual - authoritative scripture will always mean different things to different people. It was clear to me that our differences showed in the manner in which we appropriated meaning to the texts in the reading sessions. It was interesting to me and definitely a learning experience to see how reading the Qur'an places a great deal of emphasis on the manner in which scriptures have been interpreted. That additional lens of tradition, though subtle in the other faiths, provides an interesting dimension to the way authoritative scriptures make sense to readers.

Going Forward

The research project has benefited immensely from the interactions that occurred in the reading sessions, particularly and more generally in the proceedings of the conference as a whole. However, the value of any pilot rollout is in its ability to inform the road ahead for the main project. In the following few lines, I will attempt to convert the insights gained into some usable currency as the project escalates to full throttle. This is a section that is very subjective, and I am aware that I may have held on to the wrong end of the stick. For that reason, I stand open to suggestions to improve on the envisaged end product.

Convivencia is a Realisable Dream

Terence Lovat and Robert Crotty (2015:v) take note of the conspicuous fractures defining relationships across the Abrahamic faiths, 'fractures [that] have come to affect world order and threaten global wellbeing.' As the title of their project suggests and working on the conviction that history does repeat itself, Lovat and Crotty model the thesis of their work on the concept of 'the medieval Convivencia (literally "harmonious co-existence"), when Muslims, Christians and Jews lived together, relatively peacefully and cooperatively, between the eighth and the fifteenth centuries, mainly in Southern (Moorish) Spain'(Lovat and Crotty 2015:v). The story of Convivencia has been told in several ways, with highly romanticised versions available. However, it is a point in time that is often referred to as a clear example that the co-existence of the Abrahamic faiths is a realisable dream. The consequent blossoming of the general quality of life in this region during this time as evidenced by the corresponding art and architecture makes initiatives such as CIAS deserving of everyone's best shot.

It is the Convivencia ethos that underlies CIAS and this research - an ethos built upon the conviction that carefully developed hermeneutical strategies for the authoritative scriptures of these faiths can be central in bringing about social cohesion. In addition to the friendly ambiance that defined the conference, in the Qur'an reading session it was highlighted that in the selected passage, at least on two instances, the biblical Jews are referred to as Muslims. The nuanced variations distinguishing the dhimmi, who are Muslims by their monotheistic confession, from those who go all the way to believing that Alläh is but one whose final message is in the Qur'an as revealed to Prophet Muhammad notwithstanding, recognition of Jews and Christians as Muslims provides space for dialogue in my view. It is for this reason that Lovat and Crotty (2015:v) opine: 'We also contend that, as was the case [during the medieval Convivencia], the role of Islam in forging this positive coexistence remains a crucial one'. This study, as does the CIAS project, points to developing hermeneutic strategies that aim at bringing the authoritative scriptures of all three faiths into respectful dialogue.

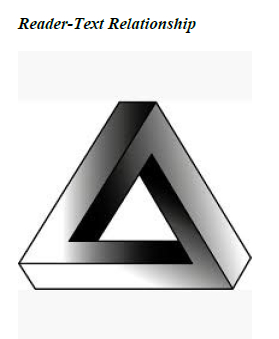

I have referred to the reader-response code above, and here I attempt to locate the same in the cartographic estimation as the project goes forward. At some point quite early in our academic journeys (Key Stage One/Early Primary School) or even before starting primary school, most of us were introduced to shapes. The triangle is one such shape, and it has been embedded in our brains to such an extent that rarely do we give it any extra attention where we see it. Above is one, right? We see it as and call it a triangle not because it is one but because we bring our epistemological make up into a shape presented to us. In this instance, the shape is not a triangle, but we make it one anyway. Actually, what we have above is known as a Penrose or impossible triangle - it does not exist.

While the Penrose triangle does not exist, the Hebrew Bible, the Christian Bible and the Qur'an are real entities held with reverence and authoritative awe in their respective faith communities. The reading sessions seemed to demonstrate that the optical illusion analogy above applies in that at the end of the day, whatever the scriptures are and whatever they may mean, what holds sway is what the reader brings into the interaction with a given text. Despite clear instructions to read the selected texts as 'a layman would', the much-valued contributions in the reading sessions, in my opinion and as often admitted, were a strong reflection of the high academic tint that provides colour to the profiles of the participants as would be expected at a CIAS Conference. The underlying premise for any optical illusion, and so is that informing reader-text relationships, is that it is impossible (or at least extremely difficult) to 'unsee' what the human mind has already seen. We cannot help but bring what we know into our interaction with data, and scriptures are not spared. I am not saying this as a critique of the pilot process but as a valuable tool as the project engages groups made up of people whose skills where exegesis is concerned may be somewhat different.

Homogeneous and Non-Homogeneous Readings

Geert Hofstede (2001:80) observes that inequality may occur in various ways following 'difference in physical and mental characteristics ... social status and prestige [;] wealth [;] power [;] laws, rights and rules.' Awareness of the presence of 'other' people inevitably kick-starts a power negotiation process that impacts outcomes in a number of ways. On this basis and in a similar project, Charlene van der Walt (2014:67) employs Michel Foucault's theory of power to keep an eye on how power plays out in Bible-reading groups. The reading sessions in discussion, for reasons of practicality, followed a non-homogeneous model in which all participants read the respective texts and conversed together. I must make it clear that my observation was that the mood was very positive (with thanks to all participants) and the discussions were quite productive. However, I could not help but wonder how the awareness of the presence of people of other faiths may have exerted a kind of power causing some holdback on what could have been the case had participants been split into their respective homogeneous faith groups. Put simply and as an example, how much freedom does a Christian have discussing their authoritative scripture in the presence of Jews and Muslims and vice versa?

From the forgoing notations, I have learned how not to do it in the protocol of the main research, which has been designed to follow the homogeneous model. The province of Western Cape, particularly the cities of Cape Town and Stellenbosch, offer a wide range of demography in such close proximity to allow for the kind of empirical study envisaged in this project. Louis C. Jonker (2015:225) makes the following notation with respect to South Africa as a whole:

South Africa is often described as "the world in one country." This slogan refers to a rich variety of climatological and vegetational regions as well as to the rich variety of peoples, cultures, languages, and religions. The slogan is often heard in contexts where attention is intentionally focussed on the positive potential of this rich diversity.

The Western Cape province is richly multiracial and multicultural, and all three Abrahamic faiths have a significant presence here. Taking this detail into account, the research design will start with putting together three groups in and around Stellenbosch comprising of university students; each group will be made up of up to 10 persons confessing to the same faith. Then I will establish three more groups made up of up to 10 adults each that will be established in and around Cape Town, again each comprising members of the same faith. The first round of meetings (one reading per session), following the preliminary introductions and inductions, will be unstructured reading where participants will organise themselves into reading a given text and deliberate on each group member's initial thoughts. They do not have to agree, but some effort to establish a meaning of the reading will be encouraged. The researcher (and associates) will be in attendance but only as observers recording the proceedings. The second round will comprise two plenary sessions, one for the Stellenbosch groups and the other for the Cape Town groups. These will be semi-structured with the groups reporting their findings. The researcher and team will be asking questions, seeking clarity where necessary and (in the end) evaluating what impact presentations by other readers would have had on original submissions. In the end, data will be collated, classified and coded.

Conclusion

I have offered a summative review of the CIAS conference reading sessions, taking liberty to arrange the material into some sort of thematic flow. I have also given an analysis of the observable hermeneutic strategies, tying them to known trends in the history of authoritative scripture reading. I am hoping to use the same strategies in codifying the data anticipated in the next exercise of the project, which includes data gathering by way of group readings by selected active members of these faith traditions. I have also converted insights gleaned in the reading sessions into some form of usable currency as the project proceeds to the main part. At this time, the project remains an ongoing piece of work, and both the host and researcher would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all participants of the 2019 CIAS Conference. We remain open for further insights and pointers. If not already reflected, the project has benefited immensely from the contributions received. For all it is worth, the possibility of contributing to a Convivencia of our time is not only a possibility but is also energising. The influence of religion on many other facets of life - politics, economics, law, social relations - cannot be overemphasised. The value of an engagement that seeks to understand, theorise and improve the hermeneutical strategies at play in religious communities' interaction with their respective authoritative scriptures is immeasurable.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adebayo, O. O. 2019. Θεόπνευστος and its implications for the concept of scripture in 2 Timothy 3:14-17 (Masters in Theology Thesis) Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Alexander, T. D. 1992 'Are the wife/sister incidents of Genesis literary compositional variants?' Vetus Testamentum 42(2): 145-153. [ Links ]

Barton, J. 1986 Oracles of God: Perceptions of ancient prophecy in Israel after the exile. London: Darton, Longman and Todd. [ Links ]

Barton, J. 1996 Reading the Old Testament: Method in biblical study. 2nd ed. London: Darton Longman and Todd. [ Links ]

Brooke, G. J. 2000 'Qumran: The cradle of the Christ?' in Brooke, G.J. ed., The Birth of Jesus: Biblical and Theological Reflections Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1998. Isaiah 1-39. Louisville, KT: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Davies, P. R. 1992. In search of "AncientIsrael". London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Freed, E. D. 2001. The stories of Jesus' birth: A critical introduction Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Gordis, D. H. 1985. 'Lies, wives and sisters: The wife-sister motif revisited', Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought 34(3): 344-359. [ Links ]

Heck, P. L. 2009 Common ground: Islam, Christianity and religious pluralism. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. [ Links ]

Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by J. Marincola (2003). London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. H. 2001. Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organisations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Jonker, L. C. 2015. From adequate biblical interpretation to transformative intercultural hermeneutics: Chronicling a personal journey. Intercultural Biblical Hermeneutics Series 3. Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies in collaboration with VU University Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Long, V. P. 2002. Introduction. In Long, V. Phillip, Baker, David W. & Wenham, Gordon J. (eds), Windows into Old Testament history: Evidence, argument, and the crisis of "BiblicalIsrael". Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Lovat T., and Crotty, R. 2015. Reconciling Islam, Christianity and Judaism: Islam 's special role in restoring Convivencia. London: Springer. [ Links ]

Mapfeka, T. K. 2018. Empire and identity secrecy: A postcolonial reflection on Esther 2:10. In Stiebert, J. and Dube, M. (eds), The Bible, centres and margins: Dialogues between postcolonial African and UK biblical scholars. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

_________. 2019. Esther in diaspora: Toward an alternative interpretive framework. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Meri, J. W. 2006. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An encyclopedia. Oxford: Routledge. [ Links ]

Meyers, C. 2001. Early Israel and the rise of the Israelite monarchy. in Perdue, L.G. (ed.), The Blackwell companion to the Hebrew Bible. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 161-86. [ Links ]

Römer, T. 2018. The role of Egypt in the formation of the Hebrew Bible. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnectionshttp://jael.library.arizona.edu 18:63-70 [ Links ]

Van der Walt, C. 2014. Toward a communal reading of 2 Samuel 13: Ideology and power within the intercultural Bible reading process Intercultural Biblical Hermeneutics Series 2. Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies in collaboration with VU University Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Wellhausen, J. 1885. Prolegomena to the history of Israel. Translated by Black, J. Sutherland and Menzies, A.. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black. [ Links ]

1 Continuous audio recordings of the reading sessions are available.

2 For details of scholars that have devoted attention to grappling with the awkwardness of the occurrence of three strikingly similar stories in such close literary proximity, see Alexander (1992) and Gordis (1985).

3 I discuss this more fully in Mapfeka (2018), a paper titled "Empire and Identity Secrecy: A Postcolonial Reflection on Esther 2:10".

4 Herodotus.

5 For a detailed discussion on genealogies and their function in relation to this aspect see Mapfeka (2019).

6 For a detailed discussion of the Pact see among others Meri (2006).