Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Scriptura

versión On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versión impresa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.120 no.1 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/120-1-2054

BIBLE INTERPRETATION IN SECULAR CONTEXTS

Past, present and future of biblical scholarship in Latvia

Ester PetrenkoI; Dace BalodeII

ILatvian Biblical Centre Norwegian School of Leadership and Theology North-West University St. John's College, Durham University

IIUniversity of Latvia

ABSTRACT

How did geo-politics and history influence the development of biblical scholarship in Latvia in the last one hundred years (1920-present)? This essay explores the three major periods of Latvia's recent history - the first period of Latvian independence (1920-1940), the Soviet occupation (1940-1990), and the second period of Latvian independence (from 1990 onwards) - and it shows that a constant throughout these three periods is how German scholarship and the historical-critical method have shaped biblical studies in Latvia. The first period of independence was considered the 'golden age ' of biblical exegesis in contrast with the period of Soviet occupation, when there was a stagnation of biblical scholarship and a disconnect with the progressive scholarly debate in the West, as well as a distorted hermeneutical framework. The revived hope of a robust biblical scholarship in the second period of independence also resurrected the long-standing dispute between the perceived liberal and conservative approaches to biblical studies and theology, and re-established the divide between the Faculty of Theology and other theological institutions. This has weakened the relationship between academic theological education and church life, and limited cooperation and biblical debate between scholars and institutions. Furthermore, longstanding German influence in biblical scholarship has been slowly giving way to a wider international scholarly community. This paper concludes that the future of biblical scholarship in Latvia needs to develop on a national and international level. Scholars and institutions need to learn how to cooperate towards robust biblical research and establish a dialogue with not just the German-speaking world but also the wider international (English-speaking) community. This will bring Latvian scholars to an environment where they can engage with and contribute to the international biblical debate.

Keywords: First independence; Soviet period; Post-Soviet period; Old Testament and New Testament scholarship; Historical-critical method; German biblical scholarship

This chapter surveys the effect of geo-politics and history on the agenda of biblical scholarship in Latvia. Since the 13th century, Latvia has been part of various empires.1The German empire had a particular influence because of the establishment of the Latvian Lutheran Church,2 and German theology and biblical scholarship have shaped biblical research in Latvia ever since.

The first period of Latvia's independence (1918-1940) saw the establishment of the Faculty of Theology at the Latvian University (in 1920) and as a result, the beginning of formal biblical scholarship in Latvia. In the first period of Latvia's independence, we will discuss the contention between the so-called liberal and conservative approaches to biblical research and its effect on the relationship between the Faculty of Theology (labelled "liberal") and the churches in Latvia, which lead to the establishment of conservative theological seminaries. Furthermore, the geopolitical ideologies of Marxism and Nazism prompted a response from some biblical scholars.

The Second World War (WWII) and the Soviet occupation of Latvia (1940-1990) led to the closure of the Faculty of Theology and the voluntary exile of biblical scholars to the West (e.g., Germany, USA) and forced exile further East (e.g., Siberia). The scholars that remained in Latvia were cut off by the Soviet authorities from broader scholarly developments, and only a few random books (not necessarily written by Latvians) were smuggled into Latvia during this period. Nevertheless, the desire to continue with biblical research was kept alive, as seen in the works of some local scholars. This study will show how limited access to current biblical scholarship affected the research of Paulis Žibeiks, Edgars Jundzis, and others.

The second period of Latvia's independence (from 1990, after the collapse of the Soviet Union) and the re-opening of the Faculty of Theology in 1991 renewed the culture of biblical scholarship. However, this renewed culture had to come to terms with a 50-year Soviet imposed gap in exposure to wider biblical research. When the local and self-taught scholars, who had remained in Latvia during the Soviet occupation, clashed with Western-educated Latvian scholars, who returned to the faculty, long-standing issues of liberal versus conservative theology flared up once again and led to tension between the church (with the Lutheran Theological Seminary) and the Faculty of Theology.3 A new generation of Latvian scholars have been encouraged to study for their post-graduate work abroad (particularly in Germany and Switzerland) with the aim of returning to Latvia and developing biblical research. Their education in German-speaking countries continues to reinforce the influence of German theology in current biblical scholarship.

The conclusion of this paper will present a synopsis of different trends of biblical scholarship in the past hundred years and a reflection on the future of biblical research in Latvia.

The First Period of Latvia's Independence (1918-1940)

This section is largely based on Jouko J. Talonen's forthcoming book, Latvian Evangelical-Lutheran Theology in 1920-1940.4 Since the 1200s, Latvia had been occupied by different Empires - German, Polish, Swedish, and by the end of the 18thcentury, Latvia was annexed by Russia. During this latter period, formal theological education (particularly of Lutheran ministers) was taking place at the University of Tartu in neighbouring Estonia (whose university was re-established by Russian Emperor Alexander in 1802, after it had been closed down byRussian forces in the Great Northern War in the year 1710). Theological education at Tartu was provided by German-speaking theologians, and the students were predominantly Baltic Germans5 (some native Latvians were also given the opportunity to pursue further studies in Theology) (Talonen, forthcoming: II.1a).

Following the Russian Revolution (1917-1923), Latvia declared its independence for the first time in 1918 (which period lasted, 1918-1940). After so many centuries under different external powers, there was now in Latvia a sense of national identity and socioeconomic optimism. It was in such an atmosphere that the University of Latvia was established in 1919 and within it, the Faculty of Theology in 1920 (Talonen, forthcoming: III.1a).

As the Faculty of Theology was part of a state university, the government declared that the Faculty of Theology ought to be non-confessional. This meant that confessional Dogmatics and Practical Theology were not initially taught at this faculty.6 Instead, historical and critical theology (implemented particularly by Kārlis Kundziņš Jr. and Jānis Sanders)7 were given particular prominence (Talonen, forthcoming:II.3).

Most docents8 and professors of the Faculty of Theology were former students from Tartu's Faculty of Theology. In the late 1800s, Tartu's Faculty of Theology saw a shift in biblical scholarship. The older generation of scholars had adhered to a conservative theology based more explicitly on the authority and inspiration of the Bible (supported by professors Friedrich. A. Philippi, Theodosius Harnack, Carl F. Keil, Johann H. Kurtz, and Arnold F. Christiani), whilst the younger generation employed historical criticism in their analysis of Scripture (supported by professors Vilhelm Volck and Ferdinand Mühlau). When the Faculty of Theology was established in Latvia, the theological approaches of Adolf von Harnack (who was himself Baltic German), Rudolf Bultmann, and Rudolf Otto shaped biblical scholarship (Talonen, forthcoming:VII).

The Faculty's theological position and the government's policy regarding the teaching of confessional dogmatics and practical theology brought opposition by the Lutheran Church (especially from bishop Kãrlis Irbe), who dubbed these decisions 'liberal policies.' This inclination by its leadership led the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia (ELCL) to establish its own pastoral training, with the foundation of the Latvian Home Mission Society (1919) and later its own theological Institute (1923-1937).9 The latter focused on the training of clergy (1923-1933) to support its parishes, and it later supplemented other church ministries within the Luteran church (1934-1937). The Institute was also a means of preserving a conservative clergy as a response to the perceived 'liberal theology' of the Faculty of Theology (Talonen, forth-coming: III.1a). This perception, as well as tension between the Lutheran Church (which included most church denominations in Latvia) and the Faculty of Theology, continues to the present day in Latvia.

The newly-independent Latvia (1918-1940), eager to imprint its national identity and reverse the social, intellectual and economic prominence of Baltic Germans, led to ethnic tensions between the two factions of society (ethnic Latvians and Baltic Germans). This tension was manifested between Baltic Germans and the University of Latvia, as well as with the Latvian clergy in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia (ELCL). Latvians wanted their institutions no longer to be run by the Baltic German minority, but rather wanted to add their national imprint both to the university and the church. This then led Baltic Germans to found their own Institution, the Herder Institute (1921).10 From a theological point of view, the Herder Institute followed a historical-critical approach as was done at the University's Faculty of Theology.

The most notable biblical scholars that made a contribution towards biblical scholarship during this interwar period were the Old Testament scholars Immanuel

Benzinger; his two students, Eduards Zicāns and Feliks Treijs; and Rudolf Abramowski. The New Testament scholars were Kãrlis Kundzins Jr., Jānis Rezevskis, Ãdams Maculãns, and Heinrich Seesemann. The German scholars Joachim Jeremias and Carl Schneider also brought valuable contributions to biblical scholarship during their tenure at the Herder Institute. The theological approaches of Adolf von Harnack, Rudolf Bultmann, and Rudolf Otto, as well as the political climate of Germany in the 1930s, influenced the contributions of Latvian biblical scholars.

Old Testament Scholarship

Immanuel Benzinger (1865-1935) (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1a) was a German professor of the History of Israelite Religion and Old Testament at the Faculty of Theology. While studying at the University of Tübingen, Benzinger had developed a historical-critical approach, initially influenced by the exegetical school of Julius Wellhausen.11 Later, Benzinger moved towards the Panbabylonian (Panbabylonismus) approach (see Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1a, fn. 206). Benzinger exhibited a particular interest on the archaeology and history of Israel and Middle East (Benzinger 1927);12 his biblical research focused on source and redaction criticism of the Pentateuch and of other books of the Old Testament (Benzinger 1921; 1924a; 1924b; 1927; 1938).13 Benzinger's wide range of research interests made him well known internationally, and he participated in a number of conferences in Germany and elsewhere in Western Europe.14Benzinger's scholarship on the history of Israel and Old Testament exegesis influenced his students, Eduards Zicāns and Fēlikss Treijs (Talonen, forthcoming:IV. 1b). Zicāns was the first ethnic Latvian scholar in Old Testament studies at the Faculty of Theology.15 His doctoral thesis (1934), titled Arābieši Vecajā Derībā un viņu attiecības pret israēliešiem ("The Arabs in the Old Testament and Their Relations to the Israelites"), was the first doctoral work in Old Testament exegesis in the Latvian language (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1b). According to Talonen (forthcoming:IV.1b), Zicāns' thesis proved controversial; nevertheless, his work was recognised by the academic community at the Faculty. Zicāns' (1937a) further research focused on the historical background of Israel's religious festivals; a now lost publication16 analysed the influence of Canaanites' human sacrifice on Israel's cult until the times of King David and of Israel's exile. However, Zicāns' later study on 'The Cult of Moloch in the Old Testament'17 argues that religious traditions of the Canaanites, as well as of the Israelites, were both founded on older Semitic religions. Zicāns (1939) also wrote a text-critical analysis of the book of Isaiah and prepared a compilation and translation of Old Testament terminology into the Latvian language (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1b, fn. 225). He also participated in the translation of the Old Testament into Latvian. From the late 1930s until 1940, Zicāns changed his research focus. His particular interest in religious history and the influence of Rudolf Otto's studies on comparative religions led him to research Latvian folk history and religion (Zicāns 1937b; 1938; Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1b). In 1944 Zicāns fled with his family as refugees to Germany, where he died in 1946.

Fēlikss Treijs (Felix Treu),18 though he did not write a doctoral thesis, proved his research abilities in his writings. Treijs (1934) wrote on the background of the Book of Ezra (Ezras grãmatas Kritika), and an article on archaeological research in Ras Shamra and its significance for the history of religions of Israel (Trejis 1935). His (1940) article on Deutero-Isaiah (Isa. 40-55) argues that the author was aware of other Middle-Eastern religions (including old Iranian religion), but that this was not the central element in Deutero-Isaiah's message. After WWII, Treijs ministered as a Lutheran pastor for the ELCL exiled in the USA and contributed to the translation of the Bible into Latvian.

Rudolf Abramowski (1900-1945) was an expert in Oriental languages, Patristics and Near Eastern Early Church history.19 Like Benzinger, Abramowski contributed significantly to biblical scholarship in Europe. Abramowski's historical-critical approach to the Old Testament was influenced by Hermann Gunkel and Martin Noth. Abramowski wrote a textual-critical paper on the Book of Ruth (Abramowski 1938a) and a religio-theological two-part commentary on the Book of Psalms (Abramowski 1939). After WWII, Abramowski was deported and conscripted to perform forced labour in Siberia, where he died in 1945.

The rise of National Socialism in Germany in the 1930s had an impact on the biblical scholarly debate on the question of the significance of the Old Testament in relation to Christ and the church; these Latvian Old Testament scholars named above contributed to this debate. Benzinger stood with the Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche) and rejected Hitler's politico-religious views (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1a). Treijs wrote against Rafael Gyllenberg's emphasis on discontinuity between Old and New Testament theology. Whereas Gyllenberg's writing comported well with the politico-religious views of Hitler, as well as with the so-called Deutsche Christen (Gyllenberg 1938:6468), Treijs (1939; cf. Abramowski 1937:63-93; Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1b, IV.1c) defended the unity of biblical theology, emphasising the dependence of New Testament theology on the Old Testament.

New Testament Scholarship

A key figure in the Faculty of Theology and in New Testament studies was Kãrlis Kundzins Jr. (1883-1967).20 He was the first professor of the Faculty of Theology in the University of Latvia (1921). Kundzins was strongly influenced by Adolf von Harnack and Rudolf Bultmann's form-historical criticism. He was a prolific writer, but his most important research was on the Gospel of John, the early church and the problem of the historical Jesus. Kundzins was the most internationally known Latvian theologian of his time and was considered, along with Imanuel Benzinger, one of the great exegetes in the inter-war period. However, Talonen (forthcoming:IV.2a-c) remarks that despite Kundzins' international attention, "he was left in the shade by the German scholars of the form-critical school".

Kundzins' dissertation (Die johanneischen Abshiedsreden) from Tartu University, as well as his first academic publication (Kundzins 1923), became the basis for his doctoral thesis in 1925, titled Topoloģiska tradīcijas viela Jāņa evaņģēlijā ('The Topological Tradition in the Gospel of St. John').21 Kundzins employed historical criticism to argue that earlier cultic traditions are behind the topological material in the Gospel of John ('holy places', and other monuments) and this explains the difference between John's Gospel and the Synoptic Gospels. Kundzins's ground-breaking work in John's Gospel was recognised internationally.22 Kundzins (1932) continued to build on his research on the Gospel of John (see also Kundziņš 1934; Lúčanský 1933), and his study (1929a:105-107) on the religio-historical background of Jesus' discourses in the Gospel of John drew some criticism in Germany,23 but praise amongst Anglo-Saxon scholars (particularly, Fredrick C. Grant) (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.2c, fn. 298). He (1935) later published an article on the dependence of Matthew and Luke's Gospels on the topography of the Gospel of Mark.

Beyond his research on the Gospel of John, Kundzins investigated early Christian tradition. Employing form-criticism, Kundzins (1929) argued that the Gospels do not present a historical narrative of the life and teachings of Jesus but that they rather present the oral traditions of the early Church (following William Wrede's position). This study brought Kundzins once again to the international scene, and it was translated into English (Grant 1962). Kundzins (1928) also wrote on views of the historical Jesus. He presented Jesus as a historical figure whose life, teachings and ministry ended on the cross. Jesus' resurrection and exaltation were not part of his analysis, as he (1931; see also Talonen, forthcoming:IV.2c, fn. 328) considered these events as a "'matter[s] of faith'". Kundzins position on the historical Jesus brought opposition from conservative Latvian scholars and clergy (even though his research was appreciated by his colleagues at the Faculty) as well as from the Social Democrats party in Latvia, who doubted the very existence of Jesus as a historical figure. After WWII, Kundzins' contribution to the topology and discourse of John's Gospel was mentioned by different international scholars until the 1990s (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.2c, fn.328). Kundzins last contribution to Johannine studies was his study on the 'I am' sayings of Jesus (Kundzins 1954:95-107).

Jānis Rezevskis (1872-1941) was a contemporary of Kundzins, but was more conservative (even though he defended historical-critical analysis) and less prominent (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3a).24 In 1930, Rezevskis (1930) wrote an article arguing that the Letter of James was not written by the Apostle James but by 'a man "in the spirit of James"', after 70 AD (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3a). The religio-political atmosphere of the 1930s seemed to have influenced his doctoral dissertation (Kundzins: 1933), in which Rezevskis engaged with the views of Ernest Renan, Adolf von Harnack and Karl Kautsky (the latter a Marxist). He argues that Kautsy's socialist views-rather than the religious context of the early Church-inform his interpretation of 'koinonia' in Acts 2:42 as 'communism' (Kommunismus). According to Rezevskis, Jesus was neither a socialist nor a capitalist because the kingdom of God transcends such values. Rezevskis's (1935:57-169) further studies included a redaction criticism of the Beatitudes (Lk. 6:2023; Matt 5:3-12), textual and redaction criticism of the Gospel of Luke (Rezevskis:1938b), a redaction and tradition criticism on the composition of the New Testament (1940) (Rezevskis 1940) and an exegetical article on justification by faith, in which he attempted to show that justification by faith in Lutheranism was based on Paul's texts (Rezevskis 1939).

Ãdams Maculãns (1864-1959)25 was a Baltic German and defended his dissertation (1933) in 1933 at the Faculty of Theology of Latvia, titled Porozis jeb sirds apcietināšanas problema Jēzus līdzībās ('The problem of the hardening of the heart in Jesus' parables'). He used textual and historical-critical analyses to understand the concept of 'hardening of one's heart' (sirds apcietināšana, porozis) in the parables found in Mark 4:11-12 and its parallels in Matt 13:10-15 and Luke 8:9-10. Maculãns challenges the authenticity of the sayings of Jesus in Mark 4:10-13, as it differs from the teachings of Mark 4:1-34 and of the New Testament. Maculãns further argued that the 'hardening of the heart' in the text is not a corporate description of the spiritual state of the people but is rather an individual state, meant as a warning to Jesus' disciples (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3b). Even though Maculãns applied textual and historical-critical approaches to his New Testament studies, he considered himself a conservative theologian, and he disagreed with the theological views of Adolf von Harnack, Rudolf Bultmann and Wilhelm Bousset. Maculãns argued that the historical Jesus presented by these scholars was not the Jesus of the Gospels and of the early church; he also defended the divine-human cooperation in the compilation of the Bible texts (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3b, fn. 354, 355). After WWII, Maculãns moved to the German Democratic Republic (i.e., East Germany, during the Cold War), where he contributed to the translation of the Old Testament into Latvian.

Heinrich Seesemann (1904-1988) was the son of the Baltic German theologian Otto Seesemann, professor of exegetics at the University of Tartu (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3c). He was a docent of New Testament exegesis at the Herder Institute (1939-1941). Like Rezevskis, Seesemann was possibly influenced by the religio-political sentiment of the 1930s, as his dissertation (1933), Der Begriff Koinonia im Neuen Testament, analysed the term koinonia from a philological and also from a theological point of view. He argues that koinonia has a double meaning - on the one hand, it connects the individual believer in Christ (anteilhaben der Christus, sein in Christus), and on the other hand, the mutual fellowship of believers (Gemeinschaft, fellowship) (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3c). Seesemann's other New Testament studies did not focus on the Gospels and the problem of the historical Jesus (as previous scholars' work did), but on the theology of the New Testament. His article (1936), Das Paulusverständnis des Clemens Aleksandrinus, on the historical theology of the New Testament, points to the divergent view on the Christian faith between Paul and Clement of Alexandria. Seeseman's (1938:175-178) article Die Gotteswissheit der Phärisäer und die Verkündigung des Paulus, argues that the converted Paul follows the teachings of Jesus based on the understanding of the relationship between God and humanity rather than on Paul's pharisaic past. Seeseman (1939) also wrote Zur Christologie des Hebräerbriefes, in which he argues that the central image of the Letter to the Hebrews is Christ as the high priest (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3c). Seesemann left Latvia for Germany in 1939.

In late 1920s, Riga was recognised as the "Centre for Baltic exegesis", and a number of well-known scholars came to lecture in Riga (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3c). Joachim Jeremias (1900-1979) and Carl Schneider (1900-1977) were both lecturers at the Herder Institute. During his time in Riga, Jeremias continued his research on the geography of Palestine and on the history of the New Testament, and published his (1926) book Golgotha (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3c). Schneider, a supporter of Germany's National Socialism and a member of the Nazi party, published a study (Schneider 1931) on the Book of Revelation and an introduction to the New Testament (Schneider 1934, see also Talonen, forthcoming:IV.3c).

WWII & The Soviet Period (1940-1990)

The Second World War was a severe blow to the nation of Latvia, which lost between 500 000 and 600 000 people through war deaths, deportation, and the emigration of refugees. During the resulting Soviet occupation, churches were considered 'harmful' by the state. Soviet oppression transformed the churches in Latvia: the Lutheran Church was changed from a Volkskirche into a minority church, and around 55% of Lutheran pastors were forced to leave Latvia (Talonen 2009:23).

WWII and the years of the Soviet occupation thereafter also severely affected the development of biblical scholarship in Latvia. In 1940, the Faculty of Theology at the University of Latvia and the Theological Institute of the ELCL were closed. Pastors and theologians were suspended, persecuted, interrogated and expelled. Most of the theological faculty left Latvia as refugees. Only three remained: professor Alberts Freijs and lecturers Arturs Silke and Arnolds Zvingis (Talonen 2009:23). Professors Ludwig Adamovich (1942) and Edgars Rumba (1943) were killed in Soviet forced-labour camps, suffering the same fate as many other Latvians (Talonen 2009:8).

The state repressed religious organisations, attempting to expel religion from public space and education. Since the official position of the state was to regard religion as unnecessary and even harmful ("the opium for the masses" in Marxist thinking), theology as a scientific discipline had no chance of being recognised. Atheistic ideology pervaded all spheres of public life - humanities and social sciences were used to spread atheistic ideology. In this context, theology survived in isolation, as biblical scholars and theologically-educated church leaders tried to continue the academic traditions started in interwar Latvia (Sildegs 2017:126-128).

The Latvian Lutheran church tried several times to establish an institute for the education of its pastors. The first attempt was made already in 1944 by the acting archbishop Karlis Irbe, who presented the plan to the Council of People's Commissars of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR). The institute would basically follow the curricula of the Faculty of Theology, and the teaching staff would be the pre-WWII alumni of the Faculty. Unfortunately, this and other attempts were unsuccessful, as the responsible institutions, mainly the Council for the Affairs of Religious Cults in Latvia and Moscow, did not support the establishment (Talonen 2009:40-42). Theological education therefore resumed only in 1954, but with limited courses. These courses were developed further towards the end of the 1960s, after the synod of the Lutheran Church decided to call these courses Academic Theological Courses. From 1976 onwards, these courses became part of the Lutheran Theological Seminary (Sildegs 2017:95).

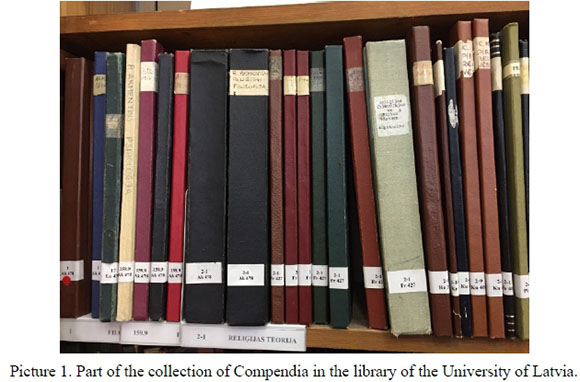

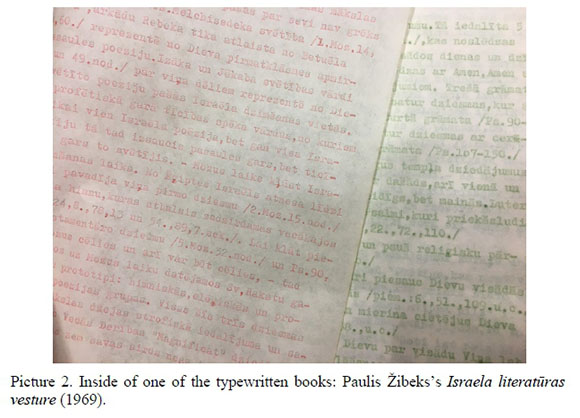

In this context, theological/biblical research re-emerged in the 1970s for the purpose of educating pastors. This period produced biblical studies in the form of textbooks (also called Compendia) which would be considered by the authorities to be academic theology. The authors of the Compendia were concerned first of all with providing the best possible education to the pastors, not necessarily with engaging in scholarly debate. In the library of the University of Latvia, one can still find the collection of the Compendia of the Theological Seminary of the Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church. This collection contains typewritten books bound in dermantine, which were reproduced by copying them by means of carbon paper. The writing and printing materials for the production and publication of the textbooks were scarce, and the authors also had limited access to biblical scholarship outside of Latvia. Pre-war biblical scholarship and resources therefore still played an important role in the compilation of biblical compendia, and these were supplemented by a few books that almost accidentally broke through the so-called Iron Curtain.

Old Testament Scholarship

The most prolific theologian of this period, was the Old Testament scholar Paulis Žibeiks (1910-2006). He had completed his studies at the Faculty of Theology at the University of Latvia in 1935. His teachers were Imanuel Benzinger and Karlis Kundzins, who, as we have shown above, were influenced by the German theology of the 1930s. One could say that Latvian theology at this time was, if not a twin, a very close sister to German theology. Paulis Žibeiks wrote his Licentiate thesis on the "Infinitive syntax in the synoptic Gospels".26 After Latvia's second independence (1990), Žibeiks was in 1992 awarded a doctoral degree for this thesis by the Latvian Academy of Sciences.27

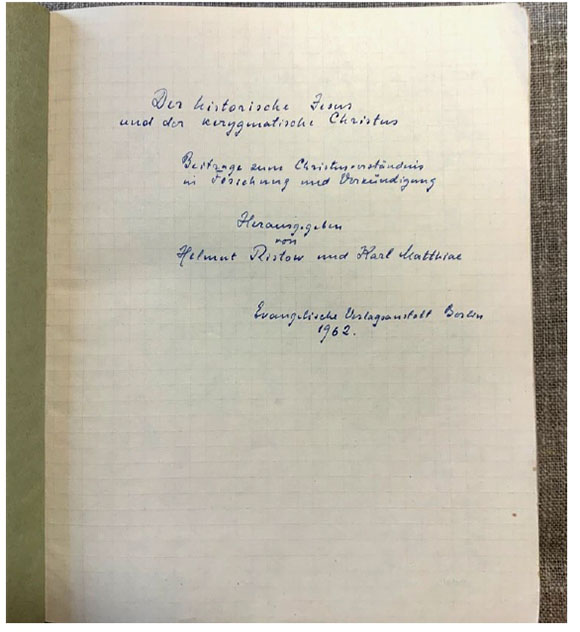

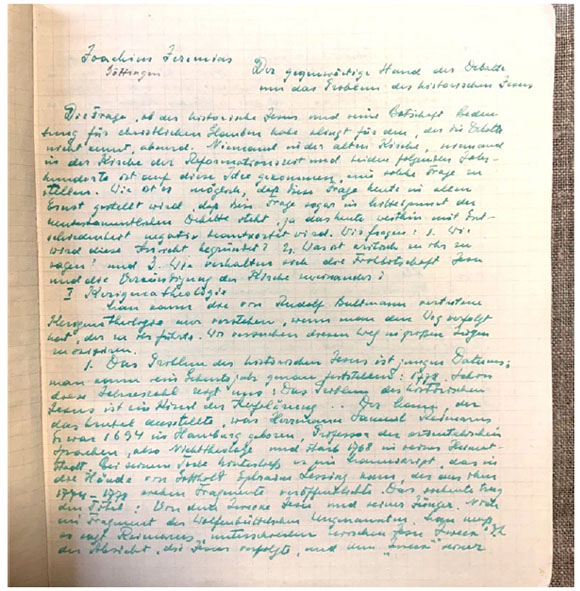

Žibeiks's long life reflects the history of theology in Latvia in the 20th century. He devoted most of his life to two tasks: working as a pastor in the church and engaging in the education of pastors and future theologians.28 In 1990, at the age of 80, he continued his work at the re-established Faculty of Theology at the University of Latvia. Žibeiks's biblical research followed the same subjects of the pre-war faculty: History of Israeli literature (1978), History of the peoples of Israel (1970), History of Israeli religion (1973), Proto-Isaiah (1974), and Exegesis of the Psalms (1975). Furthermore, the lack of theological books to educate pastors led Žibeiks to translate some well-known German theological textbooks into Latvian.29 The astonishing diligence and dedication of Paul Žibeiks to theological education is also evident in his handwritten books in his personal library.

Pictures 3 and 4. The handwritten copy by Paulis Žibeiks of a whole book - in this case: Ristow and Karl Matthiae. 1962. (Hrsg.). Der historische Jesus und der kerygmatische Christus. Beiträge zum Christusverständnis in Forschung und Verkündigung. Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. This illustrates how difficult it was for Latvian theologians to obtain theological books and how valuable such books were to them.

At the very end of the 1980's, Žibeiks decided to write his dissertation on Old Testament language (1989), but it was never defended for a doctoral degree. Looking more closely at the works of Paulis Žibeiks, it is evident that interwar Latvian biblical scholarship shaped his own biblical research; however, none of his compendia include bibliographical references and only a few have a bibliography. Sometimes there are references to an author in the text, but there is no precise reference to the cited work. An appraisal of Žibeiks's Introduction to Old Testament Theology shows that it follows Immanuel Benzinger's book of the same name.30

Methodologically, Žibeiks was comfortable with historical criticism; on the spectrum of Latvian biblical scholarship, he would therefore be counted among the so-called liberal theologians. Yet his range included also synchronic, theological and close readings of the Psalms.31

Joels Veinbergs (Joel Weinberg) is one of the scholars of Latvian origin whose work from the Soviet period is now internationally widely known. His work is exceptional in many respects, and the story of his career and the reception of his work perhaps illustrates some peculiar challenges of Latvian scholarship. Latvia's Jewish population was greatly diminished during WWII. Veinbergs (1922-2011) was a survivor of the Riga Ghetto and of concentration camps in Latvia and Germany. After the war, he became a lecturer in history at the University of Latvia and later at Daugavpils University. Veinbergs was an orientalist, one of only a few Soviet scholars permitted to work in universities on subjects such as ancient history and Jewish history-a rather different context than that of Žibeiks. Veinbergs published in Latvian, Russian and German (cf. Dion 1991:281-287), and his work was subject to scrutiny and censorship. However, publications in German journals in the 1970s, including ZAWand Klio, brought Veinbergs' work to a broader audience. Several of these German-language articles were collected and translated into English by Daniel Smith-Christopher (1992) (Weinberg 1992). Veinbergs's most important contributions to Old Testament/Hebrew Bible scholarship are these theses: Jerusalem and Yehud as a Burger-Tempel Gemeinde, a "citizen-temple community," a certain kind of economic entity within the Persian Empire; and the post-exilic development of bêt "bôt as a group in Yehud, as described in Chronicles and in the so-called Priestly literature (Dion 1991:281-287; Smith-Christopher in Weinberg 1992:1016). Veinbergs's scholarly approach to Persian-era Yehud and the biblical texts was clearly affected by the Marxist intellectual environment in which he had to work but exhibited a historian's sensitivity to different socio-economic circumstances.32

Veinbergs made aliyah in the early years after the re-establishment of Latvian statehood and thenceforth worked at Ben Gurion University of the Negev.

New Testament Scholarship

Edgars Jundzis (1907-1986) was a graduate of the Faculty of Theology (1925-1929), and his licentiate dissertation was on Albert Schweitzer's eschatological approach to the life of the historical Jesus. 33 Between 1930 and 1936, Jundzis taught in different state schools, but still continued his theological research.34 In 1936, he remained at the Faculty of Theology for research purposes, and in 1937-1938, he received a scholarship to study at the Basel and Zurich universities in Switzerland (Jundzis 2013a:224). Between the 1940s and 1970s, when the Latvian Faculty of Theology was closed down and the church was 'silenced',35 Jundzis focused on maintaining the survival of the Church (ELCL) and supporting Christians through pastoral work. This led to his arrest and deportation to Vorkuta (Siberia) from 1951 to 1955 (Jundzis 2013a:225).

Upon his return from exile, Jundzis pastored a number of churches, and later became responsible for New Testament studies at the Theological Seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia (1976) (Jundzis 2013a:225). Teaching at the Theological Seminary enabled Judzis to engage with theological issues, doing so against the backdrop of an atheistic environment. As a former student of the Faculty of Theology, Jundzis adopted historical criticism in his approach to the New Testament and like most scholars of the time in Latvia, his main theological resources were from before WWII. The scientific thinking upheld by Soviet ideology in an attempt to dispel any religious beliefs in some ways fit well with Jundzis's free-thinking and scientific method of research. He was considered not only a liberal theologian but also the most radical (and controversial) scholar of Theology of the Soviet period in Latvia (Sildegs 2017:153).

Jundzis's compendia on Pirmkristlgãs literaturas vesture ("The History of Early Christian Literature") (Jundzis 1969), Mateja evangëlija eksegëze ("Exegesis of the Gospel of Matthew") (Jundzis 1971),36Apustula Pãvila Pirmã vëstule korintiesiem ("Apostle Paul First Epistle to the Corinthians") (Jundzis 1985), and Romiesu vëstules eksegëze ("Exegesis of the Epistle to the Romans") (Jundzis 1972) engage in source and redaction criticism of the Gospels and of Paul's Letters to the Corinthians and Romans. Here, Jundzis supports the view that the Gospel of Matthew was written by a group of authors after 70AD and held that the Epistle to the Corinthians was a compilation of four letters, but his position is unclear regarding the compilation of the Letter to the Romans. Jundzis shows ambiguity on his view of the virgin birth of Jesus (in "The Gospel of Matthew") and on a future resurrection of believers (in "Apostle Paul First Epistle to the Corinthians"). On the Letter to the Romans, Jundzis seems to suggest universal salvation, whereby Jews and Greeks will ultimately be saved (thus challenging the positions of Augustine and Martin Luther). His compendia do not engage in exegetical or theological discussions of pre-war/current scholarship but rather present his personal explanation of the New Testament books. In some instances, he provides a pre-war bibliography (e.g. "The Gospel of Matthew", "Exegesis of the Epistle to the Romans"), but in other instances such acknowledgement is absent (e.g. "Apostle Paul First Epistle to the Corinthians").

Jundzis's free-thinking and unbiased scientific approach culminated in his unconventional and revolutionary doctoral thesis (1980), titled Jëzus Dzîve uz Sinoptiskâs un Johaneiskãs Tradîcijas Pamata ("The Life of Jesus on the Basis of the Synoptic and Johannine Tradition"). Jundzis builds on his previous works (including his work on Schweitzer's approach to the historical Jesus) to reconstruct the life-story of the historical Jesus established in the 1800s and 1900s. 37 Jundzis presents the inadequacies of Oskar Holtzmann, Adolf von Harnack, Wilhelm Bousset, and Frank R. Werner in their attempts to recreate the life-story of the historical Jesus based on the Synoptic traditions. Jundzis also critiques Albert Schweitzer's imminent eschatology of Jesus' life and ministry, and exposes the shortcomings of Dibelius, Schmidt and Bultmann's form-critical approach (upon which exposition kerygmatic theology is based) in their endeavour to identify the traditional materials and the edited versions found in the Gospels in the search for the historical Jesus. In order to avoid the conflicting perspectives of that time, Jundzis proposed to reconstruct the historical Jesus, based not only on the Synoptic Gospels but also on the Gospel of John (including Acts 1-5).38

Jundzis' dissertation received strong opposition, particularly from Jānis Bërzins, who stated that his thesis represented a faulty approach to the study of the historical Jesus and went so far as to label it heretical. Bërzins (1987 in Jundzis 2013a; cf, Sildegs 2017:156) characterised it as "'flowers' of decadent thinking, characterised by religious primitivism". Jundzis's dissertation is, however, also a by-product of theological research that took place during the Soviet Era. Structural (isolation) and ideological factors contributed to this path of research (Sildegs 2017:155). The impact of Jundzis's research unwittingly supported the atheistic environment of his time. As Sildegs (2017:155) observes, "Many felt compelled to rebuke Jundzis for doing a disservice to the church. In their eyes, his research resembled the radical distortion of biblical history featured by atheistic propaganda." However, other theologians (e.g. Alfons Vecmanis, Roberts Purenins and Jānis Liepins) approved of his research as scientific (Sildegs 2017:153-154). In the end, the members of the scientific committee awarded Jundzis a doctoral degree. His thesis was first published in 1993/1994, and for Jundzis's 100thanniversary (2007)39, there was a second edition with an added summary in English; his book was republished in 2013.

Second Period of Latvia's Independence: the Post Soviet Period (1990-present)

A new era in Latvian biblical scholarship began with the restoration of Latvia's independence in 1990. The initiative to re-establish the Faculty of Theology (effected in 1990) originated from the Lutheran Theological Seminary with the approval of the University Council of Latvia. Most of the lecturers at the Faculty of Theology were graduates or lecturers from the Theological Seminary, but others were Latvians who had received their education in Russia or in the West while in exile.40 The varied educational backgrounds of these theologians have shaped Latvian research and contributed to the current theological tensions between so-called "liberal" and "conservative" theologians. The faculty was initially connected with the ELCL, but due to various disagreements, the church and the faculty ultimately went their separate ways.41 After the early post-Communist years of the faculty, the teaching and biblical research was taken over by the graduates of the new faculty. German theology continued to wield great influence during this period, as all biblical scholars currently working in the faculty of theology have also been educated in German-speaking countries, influenced by German theology.

In 1999, Ralfs Kokins, the first faculty graduate of this period and with a doctorate in theology from Heidelberg, Germany, started to work at the faculty. His dissertation, supervised by the well-known German New Testament scholar Gerd Theissen, titled Das Verhältnis von ζωη und αγαπη im Johannesevangelium: Johanneische Stufenhermeneutik in der ersten A bschiedsrede Joh. 13,31-14,31, received the cum laude accolade but was unfortunately never published. In his scholarly articles, Kokins focused on various topics, as the circle of educated theologians in Latvia is relatively small; therefore, it is almost impossible to remain within one area of specialisation.42 Kokins's main academic interest in New Testament studies lies in the non-canonical literature and New Testament hermeneutics. Kokins, in partnership with other colleagues, therefore published the Gospel of Thomas (2014) and the Gospel of Philip (2017) in Latvian, each with a scholarly introduction and comments (Kokins et al. 2014; Kokins and Ralfs 2017). An article on the Gospel of Philip, published in 2012, shows that Kokin's theological views and approach to the canon are based on those of German theologians.43 His own views are shown in the appraisal of this Gnostic work: he (2012:119-120) sees its value not only as one of the first Christian's perspectives but also as a secondary narrowing of early Christian thought, which points to a psychological rather than a theological expression. Kokins (2012:120) concludes as follows on Gnostic mythology: "Gnosis, as a religiously spiritual movement, is highly subjective and amorphous, it certainly does not live on revelation, much less on historical events. All the myths of gnosis are based on the same second anthropological and cosmological depth structure characteristic of pagan archetypes: humanity itself is basically the supreme God"44 Even though Kokins's research adopted historical-critical methods, he not only approaches the canon or the Christian faith through historical lenses but also through dogmatic beliefs.

Jānis Rudzïtis-Neimanis's doctoral dissertation, "Violence against children in the family in the Old Testament" (2013, supervised by Kokins), is similarly based mainly on German theology,45 and his articles not only apply a historical-critical approach but also engage with research from the interwar period, thus forming a link with the history of Latvian theology (see Rudzïtis 2010:145-166; Rudzïtis-Neimanis 2015:41-53; 2017:189-202).

Dace Balode (co-author of this chapter) is also a graduate of the Faculty of Theology. She studied theology in Basel (1996-1998) and Berne (2000-2003), where her Master's and Doctoral theses were supervised by the New Testament scholar Ulrich Luz (19382019). Her dissertation (2011), Gottesdienst in Korinth, was defended in Tartu in 2006 and was published in Germany. The impetus to write about early Christian worship was the 1993 liturgical reform of the Lutheran Church in Latvia and was therefore also aimed at resolving current issues in church practice. Balode's (2003:71-84; 2008:5-18; 2014:79-97; 2016b:35-50; 2016a:5-20) research therefore focused on hermeneutics, with a special emphasis on gender studies, as this subject led the ELCL to abolish women's ordination.

Ester Petrenko (co-author of this chapter) is a Portuguese biblical scholar and has lived in Latvia since 2006.46 Petrenko's (2011) doctoral thesis, 'Created in Christ Jesus for good works': The integration of soteriology and ethics in Ephesians, was completed under the supervision of James D. G. Dunn and John Barclay at the University of Durham. Petrenko argues that the soteriological framework of Ephesians fully integrates the so-called theological and paraenetic parts of Ephesians (Eph. 1-3 and 4-6 respectively). Petrenko (2021:58-81; forthcoming) has continued her research on Ephesians with an article on reconciliation ("A study of Ephesians: a new identity reshaped by the Gospel of Reconciliation"), and a commentary on Ephesians with contextualisation for Central and Eastern Europe.

Conclusion

This chapter has shown that biblical scholarship in Latvia has been shaped by German theology and hence by the historical-critical method. In the first period of Latvia's independence (1918-1940), the main focus of research was on source and redaction criticism of the Pentateuch and the historical-critical analysis of other Old Testament books (e.g. Deutero-Isaiah, Ruth, Ezra and Psalms), including the study of ancient religions and the history of Israel in the Old Testament. In addition, the political ideology of the German National Socialist party in the 1930s prompted biblical scholars (particularly, Benzinger, Abramowski and Trejs) to defend academically the role of the Old Testament in relation to Christ and the church. In the field of the New Testament, German scholarship (including A. von Harnack, a Baltic German) continued to shape Latvian New Testament studies: the historical-critical method (particularly redaction criticism) was predominantly applied to the study of the Gospels and the reconstruction of the historical Jesus and the early Christian tradition. The religio-political sentiment of the 1930s influenced two doctoral theses on the meaning and significance of koinonia in the Acts of the Apostles and in the New Testament in general. Even though Rezevskis and Maculãns applied textual and historical-critical approaches to New Testament studies, they considered themselves to be conservative theologians, disagreeing with the theological views of Harnack, Bultmann and Bousset. 1920 to 1940 was a period of prolific writing, with a certain level of original work, which raised the international profile of some of the scholars who lived in Latvia; the the point that Riga was recognised as the 'Centre for Baltic exegesis', attracting a few German lecturers too.

However, WWII (1939-1945) and the Soviet occupation (1945-1990) changed the landscape of biblical scholarship in Latvia. From the major scholars mentioned above, only the New Testament scholar Kãrlis Kundzins Jr. remained in Latvia. I. Benzinger and J. Rezevskis died (1935 and 1941 respectively); Zicāns, Maculãns and Seesemann moved to Germany and Trejs to the USA. This is a period where we see the struggle for the survival of the church, accompanied by the stagnation of biblical scholarship. The modest amount of research done during this time was based on pre-WWII biblical scholarship and resources. This produced a disconnection from the scholarly debates progressing in the West and led to a distorted hermeneutical framework. The other works produced during this time were compendia on a number of biblical subjects taught at the Theological Seminary. However, the aim of these compendia was not to present a scholarly approach to the biblical books but simply to provide an overview (mostly Žibeiks's and Jundzis's own views) of these biblical books.

The second period of Latvia's independence (1990-present) has seen a renewed hope to re-establish biblical scholarship to the extent that it is as robust as it was in the interwar period (1918-1940). The Faculty of Theology of the University of Latvia was reestablished as the place for training Lutheran pastors, but very soon the relationship between the faculty and the church again became difficult. The decision to halt the ordination of women in the church played a major role in the split between the faculty and the Lutheran church.47 Furthermore, the revived dispute between perceived liberal and conservative approaches to biblical studies and theology re-established the divide between the Faculty of Theology and other theological institutions (particularly the confessional theological seminaries).48 This weakened the relationship between academic theological education and church life, and limited cooperation between scholars and institutions and consequently mutual engagement in current scholarly biblical debates.

Biblical scholars at the Faculty of Theology acknowledge that their research has benefited from international scholarship, but the local focus has been on serving Latvian readers (particularly with the translation into Latvian of the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Philip, and with studies on New Testament methodology and hermeneutics on gender studies) which results in little international exposure. Petrenko engages with and contributes towards international scholarship on Ephesians, but her work has been mostly independent of the research interests of the Faculty of Theology or other institutions in Latvia. Therefore, the cooperation between scholars from different local institutions might prove beneficial for the advancement of biblical studies in Latvia. The fact that this chapter is written by two authors from different theological institutions in Latvia demonstrates the potential for fruitful collaboration.

From this perspective, the future of biblical research in Latvia has to develop on both a national and an international level. On the one hand, there has to be a willingness and determination for a cooperation between local scholars from different theological institutions and with different approaches to biblical research. On the other hand, biblical scholars in Latvia have to establish dialogue not only with the German-speaking academic world but also with the wider international (English-speaking) community, so as to lead Latvian scholars to a climate in which they can engage with and contribute to international biblical debates.

BIBLIOGRAPHY49

Abramowski, R. 1937. Vom Streit um das Alte Testament. ThR. [ Links ].

Abramowski, R. 1938a. Eine spätsyrische Überlieferung des Buches Ruth.-In piam memoriam. Alexander von Bulmerincq. Gedenkschrift zum 5. Juni 1938, dem siebzigsten Geburtstage des am 29.Märtz 1938 Entschlafenen. AbHGHI 6:3. Riga: Plates,1938. [ Links ]

Abramowski, R. 1938b. Das Buch des betenden Volkes. Der Psalmen I. Die Botschaft des Alten Testaments 14. Stuttgart: Calwer Verlag, [ Links ].

Abramowski, R.1939. Das Buch des betenden Gottesknechts. Der Psalmen II. Die Botschaft des Alten Testaments 15. Stuttgart: Calwer Verlag. [ Links ]

Adamovičs, L. 1939. Latvijas Universitātes Teoloģijas fakultāte 1919-1939. Rīgā: LELBA. [ Links ]

Balode, D. 2003. Eine neue Identiät für Frauen in der Kirche Lettlands. Über die Suche nach biblischen Antworten zur Entwicklung der Frauenfrage in Osteuropa. in Adamiak et al. (eds) Theologische Frauenforschung in Mittel-Ost- Europa IV, ed. E. Adamiak et al. :Peeters Publishers, 71-84. [ Links ]

Balode, D. 2008. Einuhi Debesu valstības dēļ, Ceļš 59: 5-18. [ Links ].

Balode, D. 2011. Gottesdienst in Korinth. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Balode, D. 2014. Sieviete, vïrietis un Dievs jüdu romãnã 'ãJzeps un Asnãte', Dzimtes konstruësana: zinãtnisko rakstu krãjums II. Riga: LU LFMI, 79-97. [ Links ]

Balode, D., Kokins, R., Rëboks, G., Pohomova, E. 2014. Toma evangëlijs. Riga: Latvijas Blbeles biedrlba. [ Links ]

Balode, D. 2014. Sieviete, vīrietis un Dievs jūdu romānā 'Jāzeps un Asnāte', Dzimtes konstruēšana: zinātnisko rakstu krājums II. Rīga: LU LFMI, 79-97. [ Links ]

Balode, D. 2016b. God's Word in powerlessness: Towards biblical hermeneutics for women in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Latvia. in Poznan-Giezno (ed.), Friendship with the other religions-relations-attitudes. wydawnictwo poznanskiego towarzystwo przyjaciól nauk, 35-50. [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1927 (3rd ed.), 1894. Hebräische Archäologie. Dritte neu bearbeitete Auflage. Leipzig: E. Pfeiffer, 1927,3ed 1894. [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1921. Jahvist undE lohist in den Königsbüchern. Beiträge zur Wissenschaft vom Alten Testament. Neue Folge. Heft 2. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1924a. Beiträge zur Quellenscheidung im Alten Testament. LUR IX. Riga: Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1924b. Geschichte Israels bis auf die griechische Zeit. Dritte, verbesserte Auflage. Sammlung Göschen, Bd. 231. Berlin: De Gruyter & Co. [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1927. Hebräische Archäologie. Leipzig: Dritte, neu bearbeitete Auflage. [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1938. Izraëla literaturas vësture. Redigëjis doc. Dr. E. Zicāns. Rīga:Latvijas Universitate [ Links ]

Benzinger, I. 1982. Ievads Vecã Deríbã. Red. E. Zicāns. Otrs izdevums. Lincoln, NE: LELBA apg. [ Links ].

Berzins, J. 1987. Dekadencesparãdíbas müsdienu teologijã un dzivë ("Decadence phenomena in modern theology and life). Baznïcas Kalendãrs. Riga: Latvijas Ev. lut. Baznicas konsistorija, 121. In Jundzis, E. Jëzus DzívesMíklas. Rīga: Apgãds Mantojums, 227, fn.17 [ Links ]

Bousset, W. 1907. Hauptprobleme der Gnosis. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Dion, P.E. 1991. The civic-and-temple community of Persian Period Judaea: Neglected insights from eastern Europe, JNES 50(4): 281-287. [ Links ]

Embassy of the Republic of Latvia to the United States of America. "History of Latvia: A brief synopsis". https://www2.mfa.gov.lv/en/usa/culture/history-of-latvia-a- brief-synopsis. Last consulted on 08.11.2021. [ Links ]

Feldmanis, R. "Viens ievërojams gaisums". www.robertsfeldmanis.lv/lv/?ct=teologiski_raksti_2&fu=a&id=1280742274 Last consulted on 29.10.2021. [ Links ]

Grant, F.C. 1962. Form criticism: A new method of New Testament research; including the study of the Synoptic gospels, by Rudolf Bultmann, and Primitive Christianity ... light of Gospel research, by Karl Kundsin. Edited by Rudolf Bultmann and Kãrlis Kundzins. Translated by Frederick C. Grant. (Second edition). NY: Harper Torchbook. [ Links ]

Gyllenberg, R. 1938. Die Unmöglichkeit einer Theologie des Alten Testaments. In piam memoriam. Alexander von Bulmerincq. Gedenkschrift zum 5. Juni 1938, dem siebzigsten Geburtstage des am 29.Märtz 1938 Entschlafenen. AbHGHI 6:3. Riga: Plates, 64-68. [ Links ]

Heussi, K. 1975. Baznícas vëstures kompendijs: 1. Viduslaiki, 2. Reformãcija un pretreformãcija, 3. Jaunie laiki. tulk. P. Žibeiks. Akademiskie teologiskie kursi. Rīga, 1975. [ Links ]

Heussi, K. 1965. Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte. 11., verbesserte Aufl. Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, [ Links ].

Jeremias, J. 1926. Golgotha. Leipzig: E. Pfeiffer. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 1932. Charismati pirmskritigajã draudze sakarã ar Pãvila teologiju. Riga: Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 1969. Pirmkristígãs literaturas vesture. Rīga: Latvijas evangeliskãs baznïcas teologiskais seminars. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 1971. Mateja evangëlija eksegëze. Rīga: Latvijas evangeliskãs baznïcas teologiskais seminars. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 1972. Romiesu vëstules eksegëze. Rīga: Latvijas evangeliskãs baznïcas teologiskais seminars. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 1978. Jãna evangëlija eksegëze. Rīga: Latvijas evangeliskãs baznïcas teologiskais seminars. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 1980. Jëzus Dzíve uz Sinoptiskãs un Johaneiskãs Tradícijas Pamata. Doktora disertãcija. Rīga: Teologijas seminãrã [ Links ],.

Jundzis, E. 1985. Apustuļa Pāvila Pirmā vēstule korintiešiem. Rīga: Latvijas evaņģēliskās baznīcas teoloģiskais seminars. [ Links ].

Jundzis, E. 1993/1994. Jëzus DzïvesMïklas. Riga: Latvijas Zinãtnu akadëmijas Filozofijas instituts. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 2007. Jëzus Dzïves Mïklas. Riga: Latvijas Universitate ãtes Filozofijas un sociologijas instituts. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 2013a. Jëzus Dzïves Mïklas. Riga: Apgãds Mantojums. [ Links ]

Jundzis, E. 2013b. Jëzus Dzïves Mïklas. Summary in English translated by Andrejs M. Mezmalis. Riga: Apgãds Mantojums, 257-270. [ Links ]

Klauck, H. 2002. Apokryphe Evangelien. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2003. Terors un apokalipse. 11. septembris. Vãcijas teologu refleksijas, Acta Universitatis Latviensis: Oriental Studies 652:16-32. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2006a. 'Kristigãs ëtikas pamatvërtïbas - mïlestïba un pazemïba', in Teologija: Teorija un prakse. Müsdienu latviesu teologu raksti I. Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC, 132-156. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2006b. 'Vai dievnams ir svëtvieta?' in Teologija: Teorija un prakse. Müsdienu latviesu teologu raksti I. Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC, 205-221. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2007. Kurzemes vilkacu nostãsti. Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2012. Filipa evangëlijs (NHC II,3) kã sïriesu-ëgiptiesu tipa gnostiskã mïta pëtniecïbas problëma, Cels 62:99-122. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2017. Filipa evangëlijs. Rgã: Latvijas Bïbeles biedrïba. [ Links ]

Kokins, R. 2018/2019. Ëdoles baznïcas iekãrta: koktëlnieka Tobiasa Heinca 1647./1648. gadã darinãtã altãra un kanceles teologiskie vëstïjumi, Akadëmiskã Dzïve 54:38-55. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K.(Jr). 1923. Eine wenig beachtete Überlieferungsschicht im viertenEvangelium, ZNW:80. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K.(Jr). 1925 a. Topologiska tradïcijas viela Jãna evangelijã. LUR XII. Rīga: Diss. Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1925b. Topologische Überlieferungstoffe im Johannes-Evangelium. Eine Untersuchung. Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments. NF 22. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Kundzins, Kãrlis Jr. Das Urchristentum im Lichte der Evangelienforschung. Giessen: Alfred Töpelman, 1929. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1930. Adolfs Harnaks [miris] 10.6. 1930. Universitas 9 . [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1931. Kristus. Personïba, dzïve un mãciba. Rīga: A. Ranka grãmatu tirgotava. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1934 Die Wiederkunft Jesu in den Abschiedsreden des Johannesevangeliums. ZNW . [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1935. Autopsie oder Gemeindeüberlieferung? Eine Prüfung der jerusalemischen Berichte der Evangelien an der Hand ihrer topographischen Daten, Studia theologica 1:101-117 [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1936a. Ap lielo dzïves mïklu. Apcerëjumi. Rgã: Valters un Rapa. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr).1936b. Helena Kellere. Aklãs un kurlãs amerikanu meitenes brïniskie sasniegumi. Gara darbinieki. Biografisku rakstu sërija Nr. 2. Rgã: Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1939 Charakter und Ursprung der johanneischen Reden, LUR TF I:4:185-301. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1940. Neutestamentliche Offenbarungsworte, Studia Theologica II:97-116. [ Links ]

Kundzins, K. (Jr). 1954. Zur Diskussion über die Ego-eimi-sprüche des Johannesevangeliums. In Aunver, J. and Voobus, A. (eds), Charisteria Iohanni Kõpp. Octogenario oblata. Stockholm: Estonian Theological Society in Exile, 95-107. [ Links ]

Mačulāns, Ā. 1933. Porozis jeb sirds apcietināšanās problēma Jēzus līdzībās. Riga: Diss. Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Petrenko, E. 2011. 'Created in Christ Jesus for good works': The integration of soteriology and ethics in Ephesians. PBM. Milton Keynes: Paternoster. [ Links ]

Petrenko, E. 2021. A study of Ephesians: A new identity reshaped by the Gospel of reconciliation. In Faix, T., Reimer, J., and van Wyngaard, G.J. (eds), Reconciliation: Christian perspectives - interdisciplinary approaches. Reihe: Interdisziplinäre und theologische Studien / Interdisciplinary and Theological Studies, Bd. 3. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 58-81. [ Links ]

Petrenko, E. forthcoming. Commentary on Ephesians. In Constantineanu, C. (ed.), Central & eastern European Bible commentary. London: The Langham Partnership Publisher. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1932. Jekaba vestules problemas, RFR III. [ Links ]

Rebell, W. 1992. Neutestamentliche Apokryphen und Apostolische Väter. München: Kaiser-Verlag. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1933 Pirmkristietlbas un Jezus attieclbas pret ipasumu. Riga: Diss. Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1935. Die Makarismen bei Matthäus und Lukas, ihr Verhältnis zueinandund ihr historischer Hintergrund, Studia theologica I:157-169. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1938a. Vai bïbeles kritika grib un var apgãzt sveto rakstu patieslbu? Vairogs 2. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1938b. Zum Stil der Vorgeschichten des Lukas-Evangeliums. LUR TF I:2. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1939a. Ist die altlutherische Lehre von der iustitia imputa bei Paulus begründet? Zeitschrift für Systematische Theologie 2. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1939b. Vai mãclbai par 'taisnosanu ticlbã' ir vel nozlme müsu dienãs? In Evangêlija gaismã. Rakstu krãjums, veltlts Latvijas ev.-lut. Baznlcas archiblskapa Teodora Grlnberga 40 gadu mãcltãja darblbas atcerei. Rigã: Ev.-lut. Baznlcas virsvalde. [ Links ]

Rezevskis, J. 1940. Wie haben Matthäeus und Lukas den Markus benutz? Studia theologica II. [ Links ]

Ristow, H. and Matthiae, K. (Hrsg.). 1962. Der historische Jesus und der kerygmatische Christus. Beiträge zum Christusverständnis in Forschung und Verkündigung. Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. [ Links ]

Rudzltis, Jānis. Vardarbïbapret berniem gimene Vecajã Derlbã. Promocijas darbs. LU Teologijas fakultãte, Riga, 2011. https://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/bitstream/handle/7/4644/19748-Janis_Rudzitis_2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Last consulted on,23.06.2020 [ Links ]

Rudzltis, J. 2010. "Vecãs Derlbas petnieclba Latvijã (1920-1940), Cels 60: 145-166. [ Links ]

Rudzitis-Neimanis, J. 2015. Ludviga Adamovica mãcibu grãmatas par Veco Deribu, Cels 65 :41-53. [ Links ]

Rudzitis-Neimanis, J. 2017. Imanuels Bencingers un Bibeles arheologija, Cels 67:189-202. [ Links ]

Seeseman, H. 1933. Der Begriff Koinonia im Neuen Testament. Diss. Giessen: Alfred Töpelmann. [ Links ]

Seeseman, H. 1936. Das Paulusverständnis des Clemens Alexandrinus, Theologische Studien und Kritiken 5. [ Links ]

Seeseman, H. 1938. Die Gottesgewissheit der Pharisäer und die Verkündigung des Paulus. In piam memoriam Alexander von Bulmerincq. Gedenkschrift zum 5. Juni 1938, dem siebzigsten Geburtstage des am 29. Märtz 1938 Entschlafenen. AbHGHI 6:3. Riga: Plates. [ Links ]

Seeseman, H. 1939 "Zur Christologie des Hebräerbriefes." Von deutscher theologischer Hochschularbeit in Riga. AbHGHI 7:3. Riga: Plates. [ Links ]

Schneider, C. 1930 Die Erlebnisechtheit der Apokalypse des Johannes. Leipzig: Dorffling & Franke. [ Links ]

Schneider, C. 1934. Einführung in die Neutestamentliche Zeitgesichte mit Bilden. Leipzig: A. Deitchert. [ Links ]

Sildegs, U. 2017. Theology in the ghetto: The life, work, and theology of Nicholajs Plate (1915-1983), Pastor and theologian of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Latvian SSR. Helsinki: Unigrafia. [ Links ]

Smith-Christopher, D.L. 1992. Translator's Foreword, in Weinberg, J. (author), The citizen-temple community. Trans. D.L. Smith-Christopher. JSOTSupp 151; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 10-16. [ Links ]

Talonen, J.J. 2008. Latvian kansallisen teologian synty. Kiista teologian suunnasta ja taistelu pappiskoulutuksesta Latvian evankelis-luterilaisessa kirkossa 1918-1934. Studia Historica Septentrionalia 55. Rovaniemi: Pohjois-Suomen Historiallinen Yhdistys. [ Links ]

Talonen, J. 2009. Baznïca Stalinisma znaugos: Latvijas Evangëliski luteriskã baznïca padomju okupãcijas laikã no 1944. lïdz 1950. gadam. Riga: Luterisma mantojuma fonds. [ Links ]

Talonen, J.J. forthcoming Latvian Evangelical-Lutheran theology in 1920-1940, [ Links ]

Treijs, F. 1934. Iesniedzis habilitãcijas rakstu: Ezras grãmatas kritika. 27.IV. Riga:habilitëjies Latvijas Universitate. [ Links ]

Treijs, F. 1935. Quelques notes sur Ras Shamra. Studia theologicaI :201-227 [ Links ]

Treijs, F. 1939. Par Vecãs Deribas teologisko izpratni. Cels 1. [ Links ]

Treijs, F. 1940. "Anklänge iranischer Motive bei Deuterojesaja." Studia Theologica II:79-95. [ Links ]

Weinberg, J. 1992. The citizen-temple community. Trans. D.L. Smith-Christopher, JSOTSupp 151; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Žibeiks, P. 1973. Israëla religijas vësture. Riga, Akadëmiskie teologiskie kursi. [ Links ]

Žibeiks, P. 1974. Protojesaja. 1-23, 28-39. Akadëmiskie teologiskie kursi. [ Links ]

Žibeiks, P. 1975. Psalmi. Riga: Akadëmiskie teologiskie kursi. [ Links ]

Žibeiks, P. 1978. Israëla literaturas vësture. Riga: Akadëmiskie teologiskie kursi, [ Links ].

Žibeiks, P. 1989. Vecãs Derïbas valoda (Disertãcija). [ Links ]

Zicāns, Eduards. "Arãbiesi Vecajã Deríbã un vinu attiecïbas pret izraeliesiem." Riga: Diss. Latvijas Universitate, 1934. [ Links ]

Zicāns, E. 1 935. Die Hochzeit der Sonne und des Mondes in der lettischen Mythologie, Studia Theologica /:171-200 [ Links ]

Zicāns, E. 1937a. Religiskais prieks Vecajã deribã. Cels 3-5:152-160, 207-213, 288-293. [ Links ]

' Zicāns, E. 1937b. Religiskãs un etiskãs noskanas latviesu rakstniecibã. Latviesu literaturas vesture VI. [ Links ]

Zicāns, E. "Mëleka kults Vecajã Deriba." LNA LVVA (5440/1 14). [ Links ]

Zicāns, E. 1938. "Der altlettische Gott Përkons." In piam memoriam Alexander von Bulmerincq. Gedenkschrift zum 5. Juni 1938, dem siebzigsten Geburtstage des am 29. Märtz 1938 Entschlafenen. AbHGHI 6:3. Riga: Plates. [ Links ]

Zicāns, E. 1939. Pamatakmens Sijonã -Evangêlija gaismã. Rakstu krãjums, veltîts Latvijas ev.-lut. Baznîcas archibîskapa Teodora Grînberga 40 gadu mãcítãja darbîbas atcerei. Rigã: Ev.-lut. Baznicas virsvalde. [ Links ]

Zicāns, Ed. 1940. Die Ewigkeitsahnung im lettischen Volksglauben, Studia Theologia 11:41-63. [ Links ]

1 Latvia was established by the ancient people settled in the Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), known as the Balts. In the 9 Century, the Vikings ruled over Latvia, and by the 12 and 13 Century, German Knights ruled and Christianised Latvia. From the mid-16 Century to the early 18 Century, parts of Latvia were divided between Poland and Sweden, and by the end of the 18 Century, Latvia was under the control of the Russian Empire. Following the Russian Revolution (1914-1923), Latvia declared its first independence on the 18 of November 1918 and was recognised as an independent country by Soviet Russia and Germany in 1920. Latvia's independence was short lived, however, as it was incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1940 and then taken over by Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944. This was followed, once again, by the annexation of Latvia into the Soviet Union until its second independence from the Soviet Union on 21 of August 1991. Embassy of the Republic of Latvia to the United States of America. "History of Latvia: A brief synopsis". https://www2.mfa.gov.lv/en/usa/culture/history-of-latvia-a-brief-synopsis. Last consulted on 08.11.2021.

2 The Lutheran Church of Latvia is one of the main Christian denominations in Latvia.

3 The authors of this article considered the possibility of avoiding the labels "liberal" and "conservative", as they are all too often used as clichés, squeezing a variety of theological views and practices into narrow frames. However, these notions are also undoubtedly used in internal theological discourse in Latvia; therefore, the authors choose to use them. The tension between "liberal" and "conservative" theology has long roots in Latvia. First of all, these designations are related to the theological discussion and approaches in German theology (historical-critical method) at the end 19 Century and beginning of 20 Century, and opportunities for theological education in the Baltics. Until the Faculty of Theology was established in Riga 1920, Latvian theologians received their education at the University of Tartu, where theology was influenced by traditional Lutheran orthodox views. Some of the Latvian theologians were educated also in German theological institutions and were therefore influenced by more liberal views, for example, the theology of Adolf Harnack and his understanding of Christianity. The different educational backgrounds, both of which were influenced by German theology, were a precondition for the development of Latvian theology and the formation of "conservative" and "liberal" camps in the interwar period. The same could be said about the 'theologies' in the Soviet era, when the theological formation from the thirties was carried on, one could say fossilised. The hostility of the Soviet authorities to the church and theology, decreased educational opportunities in theology, and the omnipotence of criticism of religion made critical theology, such as critical Bible study, look like it speaks the same language as the oppressors. All this strengthened the positions of conservative theology. After Latvia regained its independence, religious and theological opportunities in Latvia grew rapidly, and the labels "liberal" and "conservative" obtained new meaning. Likewise, the view of the biblical text and the use of exegetical methods play an important role in understanding these concepts. On the one hand, there are be defenders of the Bible as a verbally inspired text with certain ethical norms, and on the other, theologians representing critical research. However, completely clear lines between the two camps cannot be drawn. This is shown, for example, by the question of the ordination of women, whose defence is often associated with the liberal wing of theology in Latvia, but many of its advocates and even female pastors are deeply pietistic and, in many aspects, conservative theologians.

4 Prof. Talonen granted us permission to use his research for this this section.

5 This term is used to mean "German speaking people who lived in the three Baltic countries."

6 In the beginning, the idea was to teach Philosophical ethics. However, in 1923, the university allowed the teaching of Practical Theology and Dogmatics, and from 1925, Ethics was taught as Christian Ethics. Cf. Talonen (forthcoming: 1a).

7 Kãrlis Kundzins Jr. and Jānis Sanders were the first lecturers at the Faculty of Theology.

8 In Central and Easter Europe, docent is an academic rank below that of a full professor.

9 Talonen (forthcoming:III. 1b). The death of many priests as a result of the WWI created a need for pastoral training.

10 Talonen (forthcoming:III.1c). The Herder Institute was a Baltic German university in Riga. There was no other Baltic German university in Riga between the two World Wars.

11 Particularly the source theory of the Pentateuch. See Talonen (forthcoming:IV.1a).

12 Benzinger was inspired by his Tubingen professors: orientalist Albert Socin and Emil Kautzsch, the founders of Deutsche Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas (Talonen, forthcoming:IV.1a).

13 The latter is a collection of Benzinger's lectures compiled by Eduards Zicāns in 1938, after Benzinger's death in 1935. The new edition of this monograph was later published with the title Ievads VecãDeríbã. Red. E. Zicāns. Otrs izdevums. (Lincoln, NE: LELBA apg., 1982). Cf. Talonen, Latvian Evangelical-Lutheran, IV.1a.

14 Benzinger was registered in the Index of theologians of the influential Religion in der Geschichte und Gegenwart (RGG) series in 1927. Cf. Talonen (forthcoming: IV.1a).

15 Zicāns studied at the Faculty of Theology between 1921-1926. He pursued further his studies in Berlin (1927) under Ernst Sellin and in Leipzig (1927) under Albrecht Alt. Cf. (Talonen, forthcoming: IV.1b).

16 According to Talonen (forthcoming:IV.1b, fn. 221), Zicāns wrote a 234-page monograph on 'human sacrifice in ancient Canaanite and Israelite cult'. This monograph has been lost; however, some of its ideas are found in Zicāns' article titled "Meleka kults Vecajã Derïba", LNA LVVA (5440/1 14). Cf. J.J. Talonen, Latvian kansallisen teologian synty. Kiista teologian suunnasta ja taistelu pappiskoulutuksesta Latvian evankelis-luterilaisessakirkossa 1918-1934. Studia Historica Septentrionalia 55. (Rovaniemi: Pohjois-Suomen Historiallinen Yhdistys, 2008),197.

17 "Mēleka kults Vecajā Derība",, LNA LVVA (5440 / 1 14).

18 Treijs is a Baltic German who studied at the University of Latvia, Faculty of Theology (1925-1929). Treijs then went on to study at the Faculty of Arts (Faculté de Lettres) at the University of Sorbonne, Paris, and at the Faculty of Protestant Theology of Paris (Faculté libre de Théologie protestante de Paris) between 19331934. Some of his famous lecturers in biblical research were Adolphe Lods, Charles Virolleaud, Maurice Goquel and the church historian Charles Guignebert. Treijs returned to Latvia in 1934 and lectured at the Faculty of Theology in the Old Testament. Cf. Talonen (forthcoming, :IV.1b).

19 He taught Oriental and Old Testament Studies at the Herder Institute (1929-1939). For an overview on Abramowski's work, see Talonen (forthcomingLIV.1c fn. 252-25.

20 Talonen, forthcoming:IV.2a-b. Kundzins Jr. was of Latvian and Baltic German descent. He studied at Tartu University (1903-1907) and then obtained his doctoral degree in 1925 at the Faculty of Theology in Latvia. During his studies in Tartu, Kundzins Jr. was mostly influenced by Philosophy of Religion scholar Karl Girgensohn and by the professor of New Testament exegetics, Alfred Seeberg.

21 It first came out in 1925 in the LUR-series (Latvijas universitãtes raksti) and was later republished in the series Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments (Neue Folge, 22. Heft), edited by Rudolf Bultmann and Hermann Gunkel. Cf. Talonen, (forthcoming:IV.2a-b).

22 See Talonen, Latvian Evangelical-Lutheran, IV.2c.

23 Heinz Becker critised Kundzins findings. See Talonen, (forthcoming:IV.2c fn.297).

24 He graduated from Tartu University in 1896. From 1924 onwards, he was lecturer of biblical languages at the Faculty of Theology, University of Latvia. From 1936-1940, he was professor of New Testament exegesis.

25 Talonen, (forthcoming:IV.3b). Maculãns studied at the Faculty of Theology of Tartu and in Berlin. He was a conservative theologian and was the acting director of the Theological Institute of ELCL from 1925-1931, and then director from 1931-1933.

26 The information about his thesis was obtained from Paulis Žibeiks's curriculum vitae, which was submitted at the University of Latvia and is stored in the archives of the Faculty of Theology. The thesis itself was not available to the authors.

27 His diploma can be found in the Bauska Museum of Local History and Art, which preserves the heritage of Paulis Žibeiks, including his library. Biblical scholarship was excluded from official academic life, as there was formally no theological or biblical scholarship. There was in Theology neither an official council that would elect professors nor an academic commission that would accept dissertations for defence. Despite this, with the creation of theological academic courses and later the establishment of the seminary, there was an attempt to rebuild this academic culture using the titles "professor", "docent" and "lecturer". Two dissertations were also prepared and defended in 1980, with one of them in biblical sciences, but it should be noted that most of the participants of the academic commission were without doctoral degrees, albeit with significant theological experience in the face of oppression. The repressive structures of the Soviet regime held a particular significance for all the students of theological education. The rectors of the seminaries especially were under pressure to report to the KGB on certain students and to obey the requirements of the regime. Roberts Feldmanis, one of the professors of the seminary, remembers that the rector Roberts Akmentins was pressed by the Commissioner for Religious Affairs to expel one of the students. Akmentins stood fast, and he and student were dismissed and the work of seminary was interrupted for a period of time. Cf. Feldmanis R., Viens ieverojams gaisums, www.robertsfeldmanis.lv/lv/?ct=teologiski_raksti_2&fu=a&id=1280742274 (last consulted on 29.10.2021). Theological education was, we can see, a constant balancing act between conscience and power, between existence under Soviet control and non-existence.

28 Ordained in 1936, he served as a pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church until his death in 2006. From 1947, he participated in the church examination commission, set up for those who had not been able to complete their studies before the war. This commission later developed into the body responsible for the creation of theology courses and for the establishment of the seminary in 1968.

29 For example, Karl Heussi (1965) was translated, typwritten and published in three parts - Heussi, Karl, Bazmcas vestures kompendijs: 1. Viduslaiki, 2.Reformãcija unpretreformãcija, 3. Jaunie laiki. tulk. Žibeiks (1975). .

30 For example, reporting on the sources of the Pentateuch, after a short original introduction, Žibeiks follows Benzinger's text, sometimes word for word, but also transforms the text either under the influence of another source or selecting information according to his own criteria. Žibeiks (1978:7-10); Benzinger (1982:32-37).

31 As a beautiful example, here is a fragment of his interpretation of Psalm 23:5-6, translated: "What a joy and joy to be a guest of God. In experiencing such feelings, the thoughts return to all the festive hours that the worshipper has already been able to spend in the church. How often God has set the table for him and glorified him as a kind host! Has he not in fact been a guest of his God all his life, or has he received from God's hands a rich blessing and joy? Even his enemies, who see it with dislike and envy, cannot disappoint his joy at the kindness of God and the nearness of the saints. The joy of God overcomes all the disappointments that arise in human relationships and opposites. Only one is not yet overcome - the enemy remains his enemy, the limit of his holiness that does not reach the peak of the New Testament: Love your enemies (Matt. 5:44). ... The fullness of God's blessing and the abundant light that the psalm poet sees as a reflection of his entire life, make him cry out with joy: Surely, goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life." (Žibeiks, 1975:122-123).