Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.120 no.1 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/120-1-2006

ARTICLES

A green reformation of Christianity? Anthropological, ethical and pedagogical reflections on ecology as ecumenical theme

Ernst M. Conradie

Department of Religion and Theology University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

This contribution builds upon and contributes to many recent ecumenical calls for an ecological reformation of Christianity. It seeks to guide such calls on the use of the term "ecology" by offering five brief statements in this regard, namely 1) on ecology as a transversal theme; 2) on ecology as an ecumenical theme; 3) on the root metaphor of the "whole household of God"; 4) on Christian doctrinal assumptions on such a household; and 5) on the (ecological) limitations of the metaphor of the whole household of God.

Keywords: Christianity; Ecology; Ecumenical; Household of God; Metaphor; Reformation

Introduction

Following the 500th anniversary of the Lutheran reformation in 2017, there have been several calls for a new, more specifically ecological, reformation of the whole of Christianity, including its confessional traditions, modes of reading the Bible, doctrinal distinctions, forms of praxis, rituals, ethos and spiritualities. Alongside individual contributions that will be referred to below, three important ecumenical examples may be mentioned. The first is Pope Francis'(2015) call for a comprehensive ecological conversion in Laudato Si'. The second is the so-called Volos Call (2016) entitled "Manifesto on an Ecological Reformation of all Christian Traditions", following an ecumenical consultation on "Ecotheology, Climate Change and Food Security" hosted by the World Council of Churches, Globethics.net, Bread for the World and United Evangelical Mission in cooperation with the Volos Academy and the Orthodox Academy of Crete in Volos, Greece, 12-13 March 2016 (Conradie et al 2016). The third is the Wuppertal Call entitled "Kairos for Creation: Confessing Hope for the Earth", following an international conference entitled "Together towards Eco-Theologies, Ethics of Sustainability and Eco-Friendly Churches", Wuppertal, 16-19 June 2019 (Andrianos et al. eds 2019).

This contribution is situated between the Volos Call and the Wuppertal Call, namely as a contribution to a workshop on "Green Reformation: Ecology, Religion, Education and the Future of the Ecumenical Movement", Bossey, Geneva, 12-15 May 2019. It seeks to guide such calls for an "ecological reformation" by offering five brief statements on the use of the term "ecology", namely 1) on ecology as a transversal theme; 2) on ecology as an ecumenical theme; 3) on the root metaphor of the "whole household of God"; 4) on Christian doctrinal assumptions on such a household; and 5) on the (ecological) limitations of the metaphor of the whole household of God.

1. "Ecology" has become a transversal so that not only anthropological, ethical and pedagogical perspectives on ecology are needed. The inverse also applies: Ecological perspectives on such aspects are required.

A few decades ago, the Dutch theologian and ethicist Harry Kuitert (1986) wrote a book entitled Everything is politics but politics is not everything. Something similar applies to all the major "turns" in the humanities and social sciences. Everything is historical, linguistic, hermeneutical, social, cultural, gendered, spatial and indeed also ecological (Bergmann 2007). Ecology touches on virtually every single academic discipline so that the biophysical, geological, political, economic, health, safety, ethical, philosophical, religious and theological dimensions of ecology all need to be factored in.

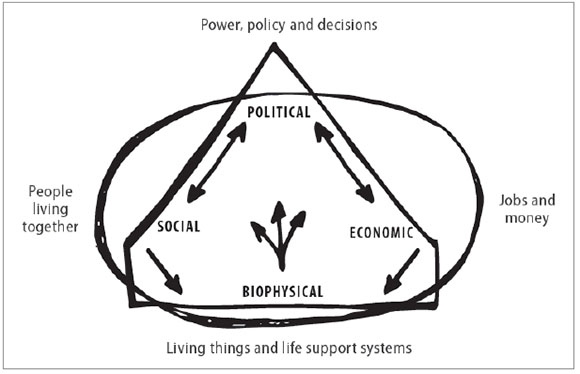

In environmental education in South Africa, a model has been developed to adopt an integrated understanding of the "environment" (often used almost interchangeably with "ecology"). This model recognises the dynamic and often mutually destructive interplay between the biophysical, social, economic and political environments in such a way that the foundational role of the biophysical environment is recognised (Conradie and Field 2016).

As a result, "ecology" is no longer something distinct; everything is ecological. This is to be welcomed even if it means that the term has become amorphous: Ecology is a dimension of everything else and cannot be treated as a topic on its own. It is a transversal alongside gender, race, finance, health, education, and so forth.

This has one important implication for any notion of green reformation:1 A reform movement can start anywhere when a particular problem is confronted (see Conradie and Pillay eds 2015). The impulse for reformation then becomes re-appropriated to address other problems in such a way that it soon becomes comprehensive. The Lutheran reformation may have started with malpractices around the selling of indulgences, but it soon had implications for many aspects of church and society. Likewise, the Genevan reformation gained momentum by inviting Calvin as a refugee to stay in Geneva, but soon he challenged the authorities for not being welcoming enough to the floods of (often wealthy) refugees flocking to the city (see Oberman 2003). This had far-reaching implications for every aspect of society and also shaped his own theology (see Conradie 2016b).

Likewise, a green transformation of the energy basis of the global economy is required, but this has implications for all other spheres, including religious traditions. Indeed, if Christianity is part of the underlying problem (as many assume), then the reformation of the Christian tradition may be crucial to addressing the problem.2 Such an ongoing reformation will almost inevitably become comprehensive, touching on issues of institution-building, readings of sacred texts, ethos, praxis, doctrine, rituals, and so forth. Given the polemical nature of such a reformation, ongoing theological reflection will certainly be required for the sake of clarification. This suggests a dialectic between reformation and critical reflection on such reformation.

2. "Ecology" has indeed been a long-standing ecumenical theme, in both a narrower and a broader understanding of the term "ecumenicity". In a project on "Ecumenical studies and social ethics" at UWC, completed in 2015, we hosted a workshop on notions and forms of ecumenicity, especially within the South African context. In a paper for that workshop I distinguished no less than 23 distinct meanings of ecumenicity (see Conradie ed. 2013b).3 Let me mention only two: the broadest meaning is one where the "whole household of God gains a cosmic significance to refer to the "universe story", where the place of humanity within cosmic, planetary, biological and hominid evolution is discussed, precisely in order to cultivate a sense of "being at home" in the universe.4 There is an obvious ecological moral propagated in this story.

By contrast, the narrowest meaning of ecumenicity is perhaps confined to institutional structures, such as the World Council of Churches, used to describe the actions of ecumenical offices, desks and bureaucrats rather than a fellowship of churches. Even in this narrow definition (sometimes criticised as "ecumenism from above"), there has been an extensive and highly impressive commitment to address ecological concerns. The following conferences and subsequent publications may serve as cairns along the way since 1975:

• The Nairobi assembly of the WCC (1975) crystallised the social agenda of the ecumenical movement through a programme emphasis towards a "Just, Participatory and Sustainable Society".

• Concerns over "Faith, Science and the Future" were addressed at a WCC world conference held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston (1979) (see Abrecht 1978; Abrecht 1980).

• The Vancouver assembly of the WCC (1983) captured the same agenda under the motto of "Justice, Peace and the Integrity of Creation" (JPIC) - in order to address economic injustices, various forms of violence and ecological destruction in an integrated way.

• This led to the so-called conciliar process that culminated in the World Convocation on JPIC held in Seoul (1990), where different priorities (on economic injustice versus violent conflict or ecological degradation) were debated (Niles ed. 1992).

• The theme of the WCC's Canberra Assembly (1991) was formulated as a prayer, "Come Holy Spirit, Renew your Whole Creation".

• This Pneumatological and the earlier Christological focus became integrated in the Harare Assembly's theme, expressed as a call rather than a prayer, "Turn to God, Rejoice in Hope" (1998), coinciding with the WCC's 50th anniversary.

• The theme for the Porto Allegro assembly of the WCC in 2006 was again formulated as a prayer, namely "God, in your mercy, transform the world". The term "world" invited a report on Alternative Globalisation Addressing Peoples and Earth (AGAPE) (Justice, Peace and Creation Team, WCC 2005). Since then, issues around trade, finance and the role of investments have been addressed in numerous ecumenical statements.

• This was followed by a study process on "Poverty and Ecology" with a series of booklets from the major world regions (see, for example, Mshana ed. 2012; Bailey 2021).

• The Busan Assembly of the WCC was again formulated as a prayer, "God of life, lead us to justice and peace". Although ecology was addressed less explicitly, it was indeed explored in terms of what a "God of Life" would mean (see Conradie ed. 2013b).

Despite such long-standing ecumenical reflections on ecological concerns, one may observe a certain tension between the narrow concentration of the term "ecology", namely with reference to the interactions between species within a particular ecosystem, and the width of ecumenical relationships throughout "the whole inhabited world". In secular discourse on ecological concerns, there is likewise a broadening of interest, namely beyond the need for nature conservation or preservation within a particular ecosystem to issues of sustainability in centres of economic power, to larger bioregions, to global "environmental" issues related to population, consumption, deforestation, overfishing, ozone depletion, ocean acidification and especially climate change. In Earth system science5 the concern is over planetary boundaries and planetary thresholds6;here the focus on the term "ecology" seems far too narrow (see Rockström 2009; Steffen et al. 2004). This is well recognised, especially in theological discourse on the so-called "Anthropocene" 7

Such a broadening of concern is also reflected in ecumenical discourse. In addition to many other ecumenical publications on ecclesial unity, Faith and Order, Life and Work, Mission and Evangelism, theological education, worship and dialogue with people of other living faiths that touched on ecology, one may mention several volumes that focused on climate change specifically, including titles such as Solidarity with the Victims of Climate Change (2002), Climate Refugees: People Displaced by Climate Change and the Role of the Churches (2013), Religions for Climate Justice: International Interfaith Statements 2008-2014 (2014),8Making Peace with the Earth: Action and Advocacy for Climate Justice (2016).9 This is complemented by numerous statements from regional, national and local churches on climate change.10

One may therefore say that "ecology" is indeed a long-standing ecumenical theme but that it seldom stands on its own. Instead, it is re-described with reference to God's creation, more specifically the integrity of creation, to a sustainable society or sustainable livelihoods, to issues of climate justice and climate solidarity, and as indicated below, especially to the whole household of God.

3. The root metaphor of the "whole household of God" has been widely used and explored to express ecumenical perspectives on ecology.

As many ecumenical leaders and scholars have recognised, the English terms "ecology", "economy" and "ecumenical" share etymological roots in the Greek word oikos (household) or oikia (house) (see, for example, Potter 2013; Raiser 1991). Ecology describes the underlying logic or principles upon which the household is built. Economy describes the rules according to which the house may be managed. The adjective "ecumenical" describes the ways in which the household is inhabited. One can improvise on this in order to also speak of ecojustice (a sense of justice that includes a concern about the interplay between ecology and economy11), ecodomy (i.e. the upbuilding of the household of God12) and so forth. In an earlier contribution, I suggested a distinction between house and home (Conradie 2005 a). If the earth is our one and only house (not heaven), then it is not necessarily our home yet, precisely because of ecological degradation. In African women's theology, a finer distinction is suggested between house, home and hearth13 to refer to the warm heart of the household where cooking takes place communally amidst much laughter and shared stories of pains and sorrows.

If the hearth constitutes the core, there are ongoing debates on the boundaries of the household. Some equate the household of God with the church, while others seek to understand the place of the church in the household of God (see Ayre and Conradie eds 2016). Some speak of a wider ecumenicity to include other religious traditions, while others recognie the need to resist idolatry and religious forms of evil, not least in the context of apartheid and consumerism (see, for example, Boesak and Hansen eds 2009). Yet others seek a cosmic understanding of the household that would include other forms of life (animals and plants) in a proverbial garden and surrounding forests. Such an all-inclusive notion of the whole household raises questions about how to include those who exclude others. This is not only an intra-human matter, as it also raises ecological questions about predation, about the distinction between household pets and household pests and about the problem of natural selection and disselection.14

4. For Christian inhabitants of the household, it is important to explore the doctrinal assumptions that they bring to the "table" (whether for food or negotiations) within such a household. They need to be honest with themselves and other inhabitants about their vision of and for the household.

It is remarkable to see how doctrinally comprehensive the metaphor of the whole household of God has become. God is the Economist (see Meeks 1996). The village of the "Father" has many huts.15 Christ is the cornerstone of the building (Eph. 2:20). The house itself is built "in the Spirit" (Eph. 2:22). The church is a temple of the Spirit. The household rituals centre around water (and sanitation), bread and wine. The story of sin and salvation16 concerns the destruction and the reconstruction17 of the household, accompanied by many ethical and pedagogical responsibilities, to prepare for the eschatological homecoming dinner. The hope of all is that the house will indeed become a home for all (see Conradie 2005b).

A crucial question concerns the place of the church in the whole household of God. Staying with the metaphor, one may consider the church as the lounge, the dinner table, the study, the kitchen, the pantry, the IT lab, the laundry room, the bathroom, the herb garden or the passage. Each of these metaphors would symbolise important aspects of an understanding of church in society. Or perhaps the church is not confined to a particular room but maintains a particular vision on the whole household, its ultimate ownership and a sense of purpose. The ecumenical movement is then best understood as moving in that same direction, namely to turn the house into a home - for all. It cannot be reduced to a fellowship of churches except insofar as this is a fellowship keeping the vision alive, one committed to the home-coming journey.

5. As is the case with any other metaphor, the (ecological) limitations of the metaphor of the whole household of God need to be recognised.

Let me mention five important caveats:

First, I already mentioned the problem of fencing, namely the question of what the household includes and excludes in order to provide protection from the rain, the sun, the wind, pests, predators, thieves and enemies (see, for example, Moltmann 2003:113- 114). In addition, there are multiple issues around food supplies in the household: Who eats what?18 Can anyone in the household live in peace if one member of the household eats another?

Second, despite attempts to offer an ecological interpretation and allusions to the shelters built by other animals, the metaphor tends to remain rather anthropocentric.19

Third, the homely metaphors may reinforce a sense of domestication and the divide between the private (the sphere of women, children and slaves) and the public (the sphere of free men) - which is rightly and widely criticised in feminist theology. However, if used inclusively, the metaphor also insists that the private is the public and thus resists such privatisation and domestication. If used in that way, an ongoing clarification will be required.

Fourth, given global divides in terms of race, class and caste, it would not do to downplay matters of the ownership of the house. To affirm that "The Earth is the Lord's" may offer a critique of the claims of landlords but could easily serve as a tacit legitimation of such claims as well. If so, the question remains a question of whose oikos it is anyway (see Cone 2001).

Fifth, the metaphor of a house acknowledges a sense of space and place, but it can easily become static and does not come to terms with issues around migration, pilgrimage or being sojourners (see Conradie 2000). It does not take evolutionary change into account, even if renovating the house can be accommodated. Nevertheless, it can be used in the face of anthropogenic climate change to focus on issues of heat, energy, water and sanitation. There is a need to guard against the hearth metaphorically catching fire, burning the whole house down. Perhaps there is then a need to juxtapose the biblical metaphor of the household with another biblical metaphor, namely the journey to the promised land - which harbours dangers of its own.

Some may suggest that the metaphor does not appeal to the homeless, landless, migrants, exiles, to the lonely, or even to those who live in comfort but whose houses have become virtual war zones. My sense is that this critique is mistaken since the tension between house and home is exacerbated by the absence not only of a home but also of a house, for example in the case of orphans, migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. It may also be possible to carry one's home along on a journey where it is necessary to move from one house to another. The metaphor may express the longing of those who have neither a home nor a house. This radicalises the recognition that "being at home" is an expression of an eschatological longing more than a sociological or psychological sense of belonging.

Conclusion

A very brief conclusion may suffice here. Any ecumenical call for an ecological reformation of the whole of Christianity needs not only to reflect on the metaphor of the household of God (oikos); there is also a need to reflect on the implied logic (logos) of that household. In a Christian context, that logic should allow for a Christological concentration, one where an interplay between all six of the classic Christological symbols (incarnation, cross, resurrection, ascension, sessions and parousia) are invited. This logic cannot be reduced to a modernist logocentrism but may require the strange wisdom of the cross.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abrecht, P.(ed.). 1978. Faith, science and the future. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Abrecht, P. (ed.). 1980. Faith, science and the future in an unjust world Volume 2: Reports and recommendations. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Andrianos, Louk et al (eds). 2019. Kairos for Creation: Confessing hope for the earth. Solingen: Foedus-Verlag. [ Links ]

Ayre, C.W. and Conradie, E.M. (eds). 2016. The Church in God's household: Protestant perspectives on ecclesiology and ecology. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Bailey, J. 2021. Poverty, Wealth and Ecology: A Critical Analysis of a World Council of Churches project (2006-2013). Masters thesis, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Bergmann, S. 2007. Theology in its Spatial Turn: Space, Place and Built Environments Challenging and Changing the Images of God, Religion Compass. 1. Available from: 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2007.00025.x. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A. and Hansen, L. (eds). 2009. Globalisation II: Global crisis, global challenge, global faith - An ongoing response to the Accra Confession. Stellenbosch: SUN Press. [ Links ]

Cone, James. 2001. Whose Earth is it anyway?. in Hessel, D.T. and Rasmussen, L. (eds), Earth habitat: Eco-injustices and the church's response. Minneapolis: Fortress Press 31-32. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. & Field, D.N. et al. 2016. A Rainbow over the Land: Equipping Christians to be Earthkeepers (edited by R. Mash). Wellington: Bible Media. 2016. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. and Koster, H.P. (eds). 2019. The T&T Clark handbook of Christian theology and climate change. London: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. and Pillay, M.N. (eds). 2015. Ecclesial deform and reform movements in the South African context. Stellenbosch: SUN Press. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2000. Stewards or sojourners in the household of God? Scriptura 73: 153-174. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2005a. An ecological Christian anthropology: At home on earth? Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Conradie, Ernst M. 2005b. Hope for the earth: Vistas on a new century. Wipf & Stock, Eugene. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. (ed.). 2013a. Ecumenical and ecological perspectives on the 'God of Life', The Ecumenical Review 65(1), 1-2, 3-165. [ Links ]

Conradie, Ernst M. (ed.). 2013b. South African perspectives on notions and forms of ecumenicity. Stellenbosch: SUN Press. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2015. The Earth in God's economy: Creation, salvation and consummation in ecological perspective. Berlin: LIT Verlag. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2016a. Could eating other creatures be a way of discovering their intrinsic value? Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 164: 26-39. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2016b. Divine election and migration: The worst possible way to address the predicament of refugees? Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2(1): 131-148. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2016c. What do we do when we eat? Part 1 & 2, Scriptura 115: 1-17. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2017. Redeeming sin? Social diagnostics amid ecological destruction. Lanham: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M. 2020. Secular discourse on sin in the Anthropocene: What's wrong with the world? Lanham: Lexington. [ Links ]

Conradie, E.M.,Tsalampouni, E. and Werner, D. (eds). 2016. Manifesto on an ecological reformation of all Christian traditions: The Volos call. in Werner, D. and Jeglitzka, E. (eds), Climate justice and food security: Theological education and Christian leadership development. Geneva: Globethics.net, 99-108. [ Links ]

Dahill, L. and Martin-Schramm, J.B. (eds). 2016. Eco-reformation: Grace and hope for a planet in peril. Eugene: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Deane-Drummond, C.E., Bergmann, S. and Vogt, M. (eds). 2017. Religion in the Anthropocene. Eugene: Cascade Books. [ Links ]

Deane-Drummond, C.E. 2014. The wisdom of the liminal: Evolution and other animals in human becoming. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Francis, (Pope). 2015. Laudato Si ': Encyclical letter of the Holy Father Francis on care for our common home. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [ Links ]

Hessel, D.T. (ed.). 1992. After nature's revolt. Eco-justice and theology. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Justice, Peace and Creation team, WCC. 2005. Alternative globalization addressing peoples and Earth (AGAPE): A background document. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Kanyoro, M.R. and Njoroge, N.J. (eds). 1996. Groaning in faith: African women in the household of God. Nairobi: Acton. [ Links ]

Kim, Grace Ji-Sun (ed.). 2016. Making peace with the Earth: Action and advocacy for climate justice. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Kuitert, Harry. 1986. Everything is politics but politics is not everything: A theological perspective on faith and politics. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Meeks, D. 1996., God the economist: The doctrine of God and political economy. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J. 2012. Science and wisdom. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 113-114. [ Links ]

Mshana, R. (ed.). 2012. Poverty, wealth and ecology in Africa: Ecumenical perspectives. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Mugambi, J.N.K. 1989. From liberation to reconstruction: African Christian theology after the Cold War. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. [ Links ]

Müller-Fahrenholz, G. 1995. God's Spirit transforming a world in crisis. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Nash, J. 1996. Towards the Ecological Reformation of Christianity, Interpretation 50(1): 5-15. [ Links ]

Niles, D. P. (ed.). 1992. Between the flood and the rainbow. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Oberman, H.O. 2003. The two reformations: The journey from the last days to the new world. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Potter, P.A. 2013. At home with God and in the world. Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Raiser, K. 1991. Ecumenism in transition: Paradigm shift in the ecumenical movement? Geneva: WCC. [ Links ]

Rockström, Johan et al. 2009. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity, Ecology and Society 14(2): 1-32. [ Links ]

South African Council of Churches, Climate Change Committee. 2009. Climate change - A challenge to the churches in South Africa. Marshalltown: SACC. [ Links ]

Steffen, Will et al. 2004. Global change and the Earth system: A planet under pressure. Berlin: Springer. [ Links ]

Stuckelberger, C. and Kerber, G. (eds). 2014. Religions for climate justice: International interfaith statements 2008-2014. Geneva: Globethics. [ Links ]

Swimme, B. and Tucker, M.E. 2011. Journey of the universe. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

1 One of the earliest calls in this regard was by James Nash, (1996:5-15). Another major recent contribution is by Lisa Dahill & James B. Martin-Schramm (2016).

2 This is the point of departure adopted in the volume edited by Ernst M. Conradie & Hilda P. Koster. 2019. The T&T Clark Handbook of Christian Theology and Climate Change. London: T&T Clark.

3 See Ernst M. Conradie (ed.), South African Perspectives on Notions and Forms of Ecumenicity (Stellenbosch: SUN Press, 2013).

4 Among the numerous contributions building on the work of Teilhard de Chardin and Thomas Berry, see Swimme et al. (2011).

5 See especially the landmark report by Will Steffen et al., Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet under Pressure (Berlin: Springer, 2004).

6 See especially Johan Rockström, et al., "Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity." Ecology and Society 14:2 (2009), 1-32.

7 For a discussion see Conradie (2020); Deane-Drummond, Bergmann and Vogt (eds) (2017).

8 See Stuckelberger and Kerber (eds)(2014).

9 See Kim (ed.) (2016).

10 One example is the South African Council of Churches, Climate Change Committee (2009).

11 See, e.g. Hessel (ed.) (1992).

12 See Müller-Fahrenholz (1995).

13 See, e.g., Kanyoro and Njoroge (eds)(1996).

14 For an exploration of such issues, see Conradie (164, 26-39).

15 For a discussion, see Ayre & Conradie (eds) (2016).

16 See Conradie (2017).

17 For the early use of the metaphor see Mugambi (1989) For the dialectic between creation and salvation using the household metaphor explicitly, see the project on creation and salvation culminating in The Earth in God's Economy: Creation, Salvation and Consummation in Ecological Perspective (Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2015).

18 There is a growing body of theological reflections on food. For a review and typology, see Conradie (2016:1-17).

19 On the role of niche construction in (human) evolution, see. Deane-Drummond (2014).