Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Scriptura

versión On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versión impresa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.120 no.1 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/120-1-1874

ARTICLES

Decolonising or Africanization of the theological curriculum: a critical reflection

Johannes Knoetze

Practical Theology and Mission Studies University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

This article presents a critical reflection on the theological curricula at (South) African Universities' faculties of theology (and religion) from a missional hermeneutic focusing on decolonisation or Africanisation. Realising that it is not sufficient merely to make a few alterations, this article takes a more practical and technical approach to amend the curricula to be more contextualised for Africa. The decolonisation or Africanisation challenge for a Faculty of Theology is threefold: (i) to address content (African contextualisation); (ii) mode/s of delivery -Open Distance Learning (ODL) and (iii) Programmes and Qualification Mix (PQM) diversity (new programmes - diplomas and certificates). The question to which this article attends is this: what are the implications of decolonisation or Africanisation in a faculty of theology at an institution of higher education in (South) Africa?

Keywords: Theological curriculum; Decolonisation; Africanisation; Missional hermeneutics; Open Distance Learning, Programme and Qualification Mix

Introduction

This article presents a critical reflection on the theological curricula at (South) African Universities' faculties of theology (and religion) from a missional hermeneutic focusing on decolonisation or Africanisation. "[A] missional hermeneutic must include at least this recognition - the multiplicity of perspectives and contexts from which and within which people read the biblical texts" (Wright 2006:39). Discussing Africa's many different development challenges, Biko (2019:2) remarks "there is a misalignment between her [Africa's] people's understanding of citizenship, her laws, norms and values, and her culture". The importance of contextualising theological education in Africa is the attempt to act theologically in ways that are both faithful to Jesus and appropriate to the people that are being educated and ministered to. Tshaka (2016) indicated that Africanisation "becomes fashionable" in public discourse in Africa today. He further indicates that Africanisation means different things to different people. This article concurs with Nkrumah (quoted in Tshaka 2016):

the defeat of colonialism and even neo-colonialism will not result in the automatic disappearance of the imported patterns of thought and social organization. For those patterns have taken root and are in varying degree sociological features of our contemporary society. Nor will a simple return to the communalistic society of ancient Africa offer a solution either. To advocate a return, as it were, to the rock from which we were hewn is a charming thought, but we are faced with contemporary problems, which have arisen from political subjugation, economic exploitation etc. (:93)

In 2014, Brunsdon and Knoetze (2014:261-279) did a critical reflection on theological education at the Mafikeng campus of North-West University from a hermeneutic of service delivery1 to assess the relevance for the Faculty of Theology's education in the African context. The conclusion of their research was that attention needs to be given to contextualisation, worldviews, and hermeneutics. I quote "By recognizing, acknowledging, and accepting one's own context, one can begin to realise that a few alterations are not sufficient, but a completely new hermeneutical key is needed to be relevant to the (new) "ancient-future" worldview in the context of Africa" (2014:277). Tshaka (2016:95) stated that there is a barrier between academic theology in South Africa and African value systems, and this makes academic theology in some instances irrelevant or impractical. This becomes clear where Black realities still take the back seat in academic theological discourse in South Africa. He continues to argue that Africa is a creation of the West and "that [a] project of Africanising knowledge production, especially within theological discourse, is urgent and vitally necessary." Biko (2019), referring to modern African state institutions and describing understandings and functioning of political parties, makes the following remark, which I find applicable to theological education:

The problem has always been how to carry out cultural readjustment. The readjustment would not be a demotion of African culture. The readjustment that is needed in culture is a better balance between the continuities of African culture and Africa's borrowing from Western culture. Until now Africa has borrowed Western tastes without Western skills, Western consumption patterns without Western production techniques, urbanisation without industrialisation, secularisation (erosion of religion) without scientification. The failure to include these core cultural codes of conduct undermines the legitimacy essential for adherence to the rules governing modern African states (Biko 2019:134-135).

It is also true that the failure to include core cultural roles/values of Africa into the 'borrowed Western' theological education undermines the legitimacy essential for a contextual African theology. Realising that the decolonisation of theological curricula will take more than only a few alterations, this article takes a more practical and technical approach that does more than just amend the curricula to be more contextualised for Africa. The decolonisation or Africanisation of a Faculty of Theology is at least threefold: (i) to address content (Africa contextualisation); (ii) mode/s of delivery - Open Distance Learning (ODL) and (iii) Programme and Qualification Mix (PQM) diversity (new programmes - diplomas and certificates). Collectively, this threefold approach puts a Faculty of Theology in the South African context with a history of more than 100 years in a transition phase. Participating and prospective churches, students, and colleagues from different and new contexts will need to adjust to this changing scenario of working with new realities (and emphases) in the Higher Education System and buy into them if we are to move forward. This contribution reflects on 'decolonising or Africa contextualisation' and theological curricula within the ambit of utilising a diversity of qualification types offered by the Higher Education Qualification Sub Framework (HEQSF). In conclusion, it elaborates on the practical consequences of a decolonised theological curriculum.

Content of the curriculum: Africanisation or Decolonisation

Many years ago, Kreamer wrote: "Strictly speaking, one ought to say that the Church is always in a state of crisis and that its greatest shortcoming is that it is only occasionally aware of it" (1961:24). This is also true of theological education. The researcher closely relates this with the understanding of context. It is in this regard that a missional hermeneutic, taking cognisance of the contexts, will help us,

What we need ... is for the Spirit of God to give us the courage and the boldness to live ex-centrically, to find our centre outside ourselves in shared commitment to the coming Reign of God, among the poor and the suffering and all others who need the message of God's grace and power. A mission spirituality can guide us to design a curriculum in which ... candidates [are equipped] to lead congregations in becoming vitally involved in God's mission of unification, reconciliation, and justice (Kritzinger 2012:44).

Acknowledging that the goal of theological education is to develop a person and not a professional shows the importance of context. This is even more true in Africa with its Ubuntu philosophy, which means that a person is only a person through other persons. Understanding this, the concepts of Africanisation and decolonisation are essential to transformational theological education. The researcher takes these concepts as two sides of the same coin and not as separate, either-or options. The understanding is that Africanisation and decolonisation inherently represent opposing methodologies: (i) Africanisation implies transformation by cultural incorporation and assimilation, a process known as inculturation (Bosch 1991:447-450). In a constructive way, one focusses on and seeks African input and insights, in this case more specific to characteristics of African Traditional Religion that can show clear differences, reinforce, or contextualise the theological curriculum. Such a curriculum will display a rich African-ness that will still carry a global influence. (ii) Decolonisation could point toward separation, destruction, and forceful removal, brought on by of the addition of the prefix de-.2 Decolonisation targets the colonial curriculum and its abolition and eradication. The focus is on what we must dispose of, do away with, discard, and root out. The end-product is a curriculum that is purged from colonialism without necessarily suggesting an African alternative and without a global relevance.

However, Maluleke (2010:372) seems to differ when he argues that the notion that African-ness be argued alongside Christianity has been viewed as suspect 'either because it is assumed that Christianity is universal or that Africanisation can only mean a lowering of universal "Christian standards" in order to fit in with some local "African standards"'. This researcher differs from Maluleke, since it has to do with different identities and with the integrity of those identities. As such, Maluleke's argument does not make sense from an academic point of view.

The following question needs to be answered: What is the function and place of theological education at a faculty of theology at an institution of higher education in (South) Africa? Amanze (2011) argues that theological education in Africa must attend to spiritual formation based on African spirituality as opposed to a clinical academic training. Louw and Mouton (2009:61) stated 'Theology without spiritual formation can easily make an "academic corpse" of theology - a positivistic practice, a rational-critical laboratory and a sterile, "clinical" or neutral value for "professional initiates"'. Painfully aware of the power hidden in religion and theological curricula (e.g. the misuse of God's Name in our history and even today in some ministries), any South African Faculty of Theology's 'decolonisation or Africa contextualisation' of its academic offering must entail (i) critical knowledge and understanding of the current challenges and underpinning issues raised in and demanded by the quest for a 'decolonised' Higher Education system in South Africa, (ii) a thorough review of the content of its curricula in existing qualifications, (iii) development in collaboration with its partner churches and ecclesiastical stakeholders in terms of (iv) PQM diversity.

In concurrence with the above, the remaining faculties of theology (and religion) in South Africa teach from the Reformed tradition. Therefore, the overall teaching philosophy of a South African faculty of theology should be to establish a vibrant and inclusive social context (safe space) that allows a diversity of ideas, worldviews and critical reflection on the Bible. Since theology can be studied only in a community, which includes not only the seminary but congregations and other organised ministries of the church, the curriculum must have as its outcome an 'African Reformed praxis' (Kritzinger 2012:36). If theological education wants to serve the church and its contexts, it must connect with the church and the context. A faculty of theology must intend to prepare students holistically for a spiritual and physical life and world of work (also in different professions as tentmakers3). Holistically, formation includes theological knowledge, ministerial skills, kingdom values, and a culture of human dignity. When a faculty of theology is aware of the paradigm shifts that have taken place in theology, ecclesiology, and society, especially during COVID-19, it needs to respond in at least the following three acknowledged teaching and learning paradigms: 1) The pedagogical paradigm, for example considering different teaching philosophies to educate students by providing them with a Biblical theology. 2) The cognitive paradigm, broadening their knowledge in a scientific method, acquiring knowledge considering module content, and student learning strategies. 3) The pragmatic or instrumentalist paradigm, with emphasis on their practical role as "useful" members of society. In this regard, an 'African Reformed praxis' model where for example 100 hours of ministry experience each year can become an integral part of the curriculum (as work integrated learning (WIL)) and the learning process.

Pedagogy

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has changed the field of education in Africa, forcing institutions of higher education to adapt much more quickly to the fourth industrial revolution than anticipated. Teaching with and through technology has created a paradigm shift, which has created new ways of teaching and learning. Instructivism, constructivism and socio-constructivism are the notable theories and practices in pedagogy. Currently, all faculties of theology in South Africa use an online platform to do theological education. Online teaching forces faculties to move from a previously more instructivist pedagogy in face-to-face teaching to a current more socio-constructivist pedagogy in the online environment.

"The basic assumptions that underlie social constructivism are reality, knowledge, learning and inter-subjectivity of social meanings. Social constructivists opine that human activity constructs reality. Reality is thus invented by society together. Knowledge is also believed to be a product of human input and is constructed socio-culturally; hence interactions with one another and their physical and social environments aids individuals in creating meanings. Learning is seen as a social activity, not a passive behavioural development shaped by external, unempathetic forces. In socio-constructivism both the learning and social contexts are crucial (Onyesolu, Nwasor, Ositanwosu, & Iwegbuna 2013:41).

Working with a missional hermeneutic, the paradigm shifts from an instructivist pedagogy towards a socio-constructivist pedagogy. This addresses the issue of contextualisation of theological education in an almost natural manner.

The cognitive paradigm

The mission document Together towards Life (Keum 2013:5) makes it clear that 'we are facing a radically changing ecclesial landscape described as "world Christianity", where most Christians either are living or have their origins in the global South and East'. Previously, mission and by implication theological education has been understood from the centre to the periphery or the privileged to the marginalised. But there has been a missional shift from 'mission to the margins' to 'mission from the margins'. This shift raises the important question: "what then is the distinctive contribution of the people from the margins?" (2013:5). We may ask, "Who are the persons from the margins?" They are the poor, the exploited classes, the marginalised races/tribes, all the despised cultures. Faculties of theology within the African context should ask themselves: 'Who are the primary interlocutors of theology? With whom are we talking and with whom are we collaborating when we read the Bible and do theology?' (West 2003:xiii). The main point is that the interlocutors of theology in Africa are the marginalised (in the eyes of the West and the North), and they have serious questions about epistemology, 'questions related to the origin, structure, methods and validity of knowledge - they do so to insist that their reflection cannot be assessed on the basis of the established epistemology of First World theology' (2003:xiii). A fundamental impact on the methodology of doing theology 'from the margins' evolved from the experience of oppression and the struggle for liberation and life.

Biko (2019:134-135) has helped me to understand the distance between the way that Western faculties of theology teach and the praxis of theology in the African church when he discussed 'cultural readjustment.' Failure to include core African cultural codes of conduct into (Western) theology undermines the legitimacy of the taught theology. The decision of African Theologians to study at foreign institutions, in foreign languages, where they are exposed to foreign value systems, 'was neither consciously made nor recognised at the time as being a turning point' (2019:135). Through a social reproduction process, these African Theologians developed a reflexive foreign bias, which is accelerated through the theological curriculum.

Broadening theological knowledge in a scientific method at faculties of theology in Africa, the following positive outcomes need urgent consideration: First, there is a significant contextualised theological knowledge investment opportunity within the African Initiated Churches (AICs); twinned with 'world Christianity' it can benefit contextual theological knowledge at faculties of theology. Second, faculties of theology should appreciate diversity. 'The central challenge is how to widen the network of participating churches and individual students, without alienating these established partners altogether' (Kritzinger 2003:39). This must happen within an ethos of 'roots and wings'. Third, in broadening theological knowledge in Africa and contextualising theological education, faculties of theology must commit to what West has described as

reading "with" the participants [churches/students], rather than reading "for" them, required that I acknowledge and foreground my own contribution to the reading process, which was constantly encouraging and facilitating a close and careful reading of the text. The substantive contribution come from the resources, categories, concepts, and experience of ordinary readers (2003:6)

Fourth, faculties of theology should promote 'ecosystems' with embedded social capital in the form of universities, churches, faith-based organisations, Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) involved in community development and other communities with strong cultural linkages.

The pragmatic or instrumentalist paradigm

To train and develop ministers at theological faculties as "useful" members of society, faculties need to work with missional hermeneutics. It is necessary to help students of theology to develop a viable method of doing contextual theology and ministry by gaining essential theological knowledge, ministerial and entrepreneurial skills, and kingdom values that will enable them to think on their feet in any context. One of the limitations of theological education at faculties of theology in South Africa up to around 2018 is the fact that only graduate courses were presented. A further limitation was that these programmes were developed specifically for the training of pastors in mainline missionary churches without a clear focus on the context of Africa. Because the focus was only on graduate courses, most of the already practising pastors in the African Independent and other churches were excluded. The need from the ecclesiastical market in (South) Africa is to empower new and practising pastors in Africa with sound academic theology, but also with personal empowerment and "soft skills". Yet another limitation of theological education at faculties of theology is the underplayed role of theology across other disciplines, for example, ethics in economics or politics or pastoral care in nursing. Faculties of theology must therefore develop new qualifications, such as certificate and diploma courses, some of them interdisciplinary, to establish theology more clearly as a contributing discipline at the institutions of higher education.

Modes of delivery4

When doing theological education with a missional hermeneutic together with churches and students from the margins, the mode or method of delivery plays an important role. Dealing with contextualising theological education in Africa and/decolonisation has to do, not only with the content of the curriculum but also access to such an education. Access to theological education is influenced and even determined by the mode of delivery, for example contact (face-to-face), correspondence (paper-based), online (electronically) and hybrid (a combination of contact and correspondence or online).

Contact education

Many are convinced that holistic theological education can take place only in a face-to-face teaching and learning environment, in other words, in contact classes. Although there are indeed many benefits to face-to-face contact classes, there are also some negatives: affordability or costs is one. Although contact classes can also happen in different modes, for example, daily or in block courses for a week every two months, they are usually very expensive, since students must relocate for the time of contact classes. There is a sharp discrepancy between expected theological standards and financial means. The African context and the church of Africa give clear indications of this when up to 85% of all ministers in African churches have no formal theological education. When marginalised and poor churches are trained at institutions of higher education, the question is as follows: why would a poor or relatively poor church expect its ministers to study for at least three years to obtain a theological degree? Is training students to minister in struggling township-and-village churches in Africa the same as training ministers to serve in affluent suburban churches? This does not imply that township-and-village ministers must get a lesser theological education; it means that they might need a different theological education. We will attend to the possible different objectives of the education when the PQM diversity is discussed.

Correspondence education

The question remains: Who are the primary interlocutors of theology? In Africa, it is Africans, people who are viewed and, in many instances, treated by the North and the West as marginalised people, implying that Africa does not have the same sociopolitical, educational, and technological resources as other continents. Theological Education by Extension, also known as TEE, is one of the most well-known correspondence courses in Africa. It differs from other correspondence courses in the sense that there are some group discussions build into the programme (Thornton 1990:9).

Correspondence courses in this article are viewed as paper-based and via 'snail mail'. It is necessary to make the distinction between paper-based correspondence/distance learning and electronic distance learning which will be discussed as online learning below. In the context of South Africa, paper-based correspondence courses also become more expensive due to the deterioration of the post office infrastructure. Another attribute of correspondence learning is the lack of interaction between students as well as between students and lecturers. A further challenge is the time it takes between handing in of assignments and receiving the results; in many instances, this occurs without personal feedback on the assignment done. Many students may have other negative experiences, although I am certain that many have some positive experiences as well.

Online education

The COVID-19 pandemic that struck the world in 2020 changed the discussion about online training in all sorts of ways. It is no longer a debate about whether this is an acceptable method for theological education; the question moved to: How it can be used most effectively. It is, however, important to realise that online teaching is not just dropping information on electronic platforms or making a few YouTube videos while you are teaching. Online teaching has to do with a whole new culture of teaching, where the classroom is transformed with the sophisticated use of technology. Cloete (2015:146) distinguishes between three stages of online teaching: "Stage one, where technology is used to teach together with electronic library management; stage two, in which educators try to replicate what they do in the class to some online mediated form; stage three, which includes responses on individual and institutional level".

Attending to decolonisation and Africanisation of the theological curriculum, it would be irresponsible to assume that technology and online teaching help and create better opportunities for all students. Think of theological students from Africa, who are in many instances older or more mature people, who are in the ministry for a while and who want to better their theological knowledge, and who have limited knowledge of electronic communication. It is also exactly because it is more mature students who enrol and who are not able to move to a theological institution that the online education's most valuable contribution is the creation of greater access, especially for the marginalised groups. However, as was apparent with the COVID-19 switch to online training in South Africa in 2020, online training clearly brings forth the division between those who have access to data, technology, and technological skills and those who do not have it. Thus, while online training can give greater access to students, it might also exclude, for example, the marginalised in rural areas.

Online teaching could place an extra workload and pressure on academics since theological knowledge may not be reduced to information but must always be presented in a holistic way for the transformation of lives. "Theological training is not only about transferring information, but also requires critical engagement with what is known, is needed in order to transform the knower, and create a responsibility towards what is known" (Cloete 2015:151). Taking this into cognizance, communication, and the creation of an online community of practice5 that includes a social presence (setting the climate), a cognitive presence (selecting the content) and a teaching presence (getting the different inputs) create an environment for self-directed learning (SDL). The new culture mentioned earlier refers to a culture of SDL and is enhanced by the community of practice.

Programme and Qualification Mix (PQM)

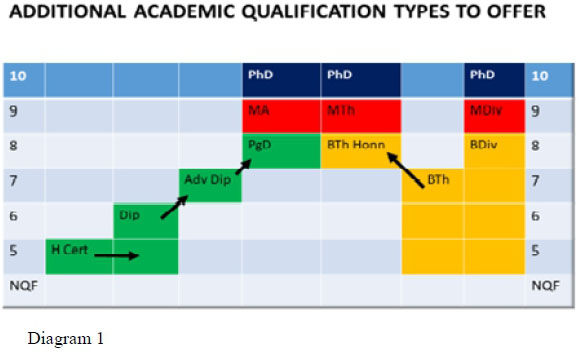

A critical analysis of the faculties of theology's academic qualification offerings indicates that it is limited in two ways. (See diagram 1 below)

1. The faculties under-appreciate and inadequately utilise the HEQSF by restricting themselves to the ambit of degree programmes only. (See the yellow path in diagram 1)

2. Although different qualifications are designed in support of excellent progression routes, the consequential restriction of permeable boundaries hampers the flexibility allowed by the HEQSF. It impedes the diagonal, vertical and horizontal articulation to a wide range of cognate qualifications. (See the green path in diagram 1)

Faculties of theology need a type of turn-around strategy prioritising a thorough augmentation of the academic programmes offered to enhance accessibility. As indicated above, theological education is holistic; therefore, programmes in all theological qualification programmes should develop a broad range of skills and competencies. These can be embodied in four generic outcomes and consequently relate to (i) substantiated and integrated knowledge, (ii) effective communication, (iii) service leadership, and (iv) creative problem solving. Different qualification types offered by the HEQSF provide significant opportunities through the National Qualification Framework (NQF) to design a flexible, dynamic, and meaningful academic offer addressing the mentioned challenges.

It is proposed that faculties of theology will have less programmes but include the following qualifications together with degree qualifications as part of the decolonisation or Africanisation process. In this manner, opportunities for training and further education will be created for marginalised and previously disadvantaged groups.

Higher Certificates

Considering Africanisation, faculties of theology need to signal to a wide range of denominations their commitment to inclusiveness, credibility, integrity, quality, and willingness to expand their qualification offerings to include entry-level tertiary programmes. In response to the challenges facing previously disadvantaged denominations pertaining to ecclesiastical training requirements, new partnerships need to be formed. From the Christian ministerial context in Africa, persons entering Christian ministry as leaders or serving in Christian ministry often do not possess any formal (tertiary) theological education. Lack of knowledge frequently gives rise to questionable practices and conventions. In extreme cases, cults are formed, which not only mislead, exploit, and even threaten adherents but indeed undermine the Christian community by bringing it under suspicion. In some cases, the community at large is imperilled and the constitutions and legislations of countries are compromised. Most infamous in this regard was the (televised) life-threatening use of insecticides for curing and healing purposes in South Africa.

In addressing these issues, denominational leaders voiced their respective denominations' concerns and pleaded for opportunities to have access to university-level training for ministerial candidates. The consensus reached indicated that faith communities require education that provides for (1) access to and opportunities of success in tertiary education and (2) vocational education that would be valued and recognised. It was concluded that faith communities and denominations thus need:

• an entry-level bridging qualification that will prepare candidates meaningfully to be successful in high-quality education in Theology and Ministry,

• a recognised qualification for serving pastors with no formal theological education, to enhance their ministry and to provide an articulation pathway for possible further and continuous education at the same time,

• a qualification for local leaders serving in churches often destitute of full-time pastors, providing a skill set in ministry and church administration.

As such, a Higher Certificate in Theology should be carefully designed to address the identified need of the ecclesiastical sector. At the national level, such a programme contributes to the National Plan to Implement NQF 5 qualifications at South African Universities and Colleges. The qualification serves to provide students, including those who opt for further tertiary training, with the basic introductory knowledge, cognitive and conceptual tools, and practical techniques in the field of Theology and Christian Ministry. After completion, candidates should be able to demonstrate a good knowledge of general principles together with more specific procedures and their appropriate application within the ambit of Theology and basic Christian ministry, as well as good practices as far as church keeping is concerned.

Diplomas

Various denominations voiced their concerns and pleaded for opportunities to have access to university training for ministerial candidates. In discussions with different denominations, it was clearly indicated that faith communities require leaders who:

• possess detailed knowledge and understanding of the Christian faith as it relates to Christian Ministry.

• are equipped with a skillset that would enable them to perform the duties related to the management, edification and pastoral care of faith communities and individuals; in particular, the aged and the youth who are exposed to and living in poor marginalised communities.

• will have the ability to place their knowledge and understanding within the context of broader societal trends and developments.

• understand their social, civic, and environmental responsibilities within the context of Christian Ministry and their role as leaders, and commitment to social justice, democracy, human rights, and the integrity of the environment, manifested in conduct that respects and upholds the rights of individuals, groups, and communities.

• will take full responsibility for their decisions and actions and the decisions and actions of their faith communities, including the ethical implications of these decisions and actions.

• can work and communicate effectively and coherently in groups.

• have the capacity to solve problems appropriately.

• will be life-long learners.

Considering the above, tertiary education is seen as the only way to build intellectual and vocational capacity that would result in meaningful Christian ministry. The industry therefore needs informed, well-educated leadership that will be able to demonstrate the ability to integrate vocational and applied ministerial knowledge and related methods and procedures. Diploma graduates should be able to understand general theoretical principles underpinning Christian ministry, as well as to assimilate and combine in an accountable way general and specific ministerial duty, practices, procedures, and their application in a ministerial setting. They also will have to be able to substantiate their worldview and the principles that inform their conduct; this is identified by stakeholders as a vital contribution to significantly increasing the level and accountability of theological and ministerial knowledge. Students should be able to interpret curriculum content based on their own experiences, according to their cultural norms, personal belief systems, preferences, and backgrounds, and to share their interpretations with fellow students as valid and valued real-life experiences.

Post-graduate Diplomas

The majority of churches and denominations in South Africa require for entry into Christian ministry the completion of three years of training. Most graduates leading churches and faith communities consequently hold a general formative bachelor's degree, diploma, or equivalent qualification. Many of these women and men serve as distinguished leaders in communities, where they play a significant role in addressing a wide range of socio-economic and developmental challenges: poverty, violence, crime, anger, education, service delivery, etc. Among their ranks exists a dire need for further vocational education, so that ministers can become sources of information and better serve the communities in which they work. To contribute in a meaningful way to public life, to the common good, to serve in religious communities more proficiently and to lead personal lives that are underpinned by the critical capacity, purposefulness, and a values-orientation that would identify them as service leaders in all spheres of life demand a higher-level skill set underpinned by theoretical engagement and intellectual independence.

At the same time, a growing number of graduates holding a bachelor or bachelor Honours degree in, e.g., Psychology, Social Sciences, Community Development, Communication, etc., want to enrol for advanced studies and in-depth knowledge of interrelated theological disciplines (e.g., Pastoral Care) to acquire appropriate theological education with a view to specialisation on Master's level and pursue professional careers in, specifically, pastoral care, youth care, or church development, ecclesiastical journalism or communication.

Interdisciplinary qualifications

Considering the student market for theology, decolonisation must also be understood in terms of accessibility, affordability, and job opportunities. Due to different sociopolitical factors, it is realised that many students who are called to ministry do not have access to Higher education. Furthermore, others who finished their theological education might not be able to enter full time ministry because congregations cannot provide for their daily needs or salaries. Faculties should therefore attempt to make Higher Education accessible to students at different stages through different qualifications and with different career opportunities. Taking employability into account, African students will benefit if these qualifications can be interdisciplinary. The content of interdisciplinary qualifications may consist of 50% theological content and 50% content in other disciplines like, nursing, education, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, et cetera. The design of the relevant interdisciplinary qualifications should maximise the 50% rule to be as flexible as possible to support diagonal, vertical, and horizontal articulation into qualifications. This would enable holders of (interdisciplinary) qualifications in theology to pursue a variety of careers, including NGO work, youth work, community services, journalism, media, teaching, or occupations that are concerned with people and their values, community development, community care, social services, and disaster and relief management. Theology graduates will thus find access to a broad variety of career or second career opportunities.

Practical proposal for the Africanisation of the existing theological degree curricula

This section of the article suggests possible practical ways to transform an already established curriculum in phases over a three-year period.

First year:

• At least one study unit within every module deals with a typical African topic, e.g., beliefs, healing, gender, HIV/Aids, racism.

• At least two pre-scribed sources/articles within the module need to be from African scholars.

Second year

• At least two or three study units within every module deals with a typical African topic, e.g., beliefs, healing, gender, HIV/Aids, racism.

• At least three prescribed sources/articles within the module are from Black African scholars.

Third year and onwards

• Biblical subjects and Dogmatics: at least 50% of the study units in each module deals with a typical African topic, may be, beliefs, healing, gender, HIV/Aids, racism.

• Practical theology; Missiology; Church, Dogma and Mission History; Ethics; except from at least 50% of the study units in every module there needs to be at least one complete module within the subject field focussing, specifically on Africa.

Teaching and Learning

Decolonisation or Africanisation does not focus only on what is taught but also on who is teaching and from where the teaching takes place. In this regard, the faculty will have to give serious attention to:

• The staffing component related to gender and race.

• Distinguishing between academic teaching and the church's own programmes.

• Make use of electronic platforms to engage with African scholars in the field and from other institutions.

Conclusion

This article attended to and focussed on the decolonisation or Africanisation of theological education. Attention was given to curriculum contents, modes of delivery and the PQM, as well as practical suggestions to Africanise existing degree qualifications. Broadening the scope of, and access to theological qualifications also asks of the church to adopt a missional approach, where the ministry does not belong to the clergy alone. A good example is the new development within the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa, in which the structured ministry within the church is broadened in the following ministerial lanes: Minister (full time minister in a congregation), parttime minister (minister who works part time in a congregation), categorial minister (standplaasleraar) (minister within a specific group of people, usually immigrants, such as Portuguese-speaking people), a service minister (diensleraar) (a minister with a specific calling in a congregation, for example, youth ministry or diaconal ministry) and lastly servants (bedienaars) (mature members of the congregation with a calling to preach). All these different ministries are attended to and require different theological qualifications. Because different congregations in the different contexts of Africa require different qualifications, faculties of theology in Africa must answer to the needs of the marginalised church.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amanze, J.N. 2011. Contextuality: African spirituality as a catalyst for spiritual formation in theological education in Africa, Ogbomoso journal of Theology 16(2):1-23. [ Links ]

Biko, H. 2019. Africa, reimagined. Reclaiming a sense of abundance and prosperity. Cape Town & Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991, Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Brunsdon, A, & Knoetze, J. 2014. Batho Pele (People First) some ethical and contextual reflections on Theological education in an African context. In Mokoena, M.A. & Oosthuizen I. (eds.), Nuances of teaching and learning research, Research and Publication, Book series, Vol 3 (1) 2014. Potchefstroom: Andcork Publishers: 261-280. [ Links ]

Cloete, A. 2015. Educational technologies: Exploring the ambiguous effect on the training of ministers, in Naidoo, M (ed.), Contested issues in training ministers in South Africa. Stellenbosch: SUN Media, p 141-154. [ Links ]

Keum, J. 2013. Together towards life. Geneva: World Council of Churches. [ Links ]

Kreamer, H. 1961. The Christian message in a non-Christian world. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, K. 2012. Ministerial formation in the Uniting Reformed Church in South Africa: In search of inclusion and authenticity. In Naidoo, M. (ed), Between the real and the ideal. Ministerial formation in South African churches. Pretoria: Unisa press, 33-47. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J. & Mouton, E. 2009. Die Fakulteit Teologie op die wipplank tussen verrassing en ontnugtering, waarheid en pyn. In P Coertzen (ed.), Teologie Stellenbosch 150+, Wellington: Bybel-Media, 53-72. [ Links ]

Maluleke, T. 2010. Of Africanised bees and Africanised churches: Ten theses on African Christianity. Missionalia 38(3):369-379. [ Links ]

Nkrumah, K. 1967. African Socialism revisited, http://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/nkrumah/1967/african-socialism-revisited.htm, viewed 24 May 2018. [ Links ]

Onyesolu, M. O., Nwasor, V. C., Ositanwosu, O. E., Iwegbuna, A. N. 2013. Pedagogy: Instructivism to socio-constructivism through virtual reality. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications',4(9), 40-47. [ Links ]

Thornton, M. 1990. Training T.E.E. leaders. A course guide. Nairobi, Kenya: Evangel Publishing House. [ Links ]

Tshaka, R. S. 2016. How can a conquered people sing praises of their history and culture? Africanization as the integration of inculturation and liberation, Black Theology, 14(2): 91 -106. [ Links ]

West, G. O. 2003, The academy of the poor. Towards a dialogical reading of the Bible. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Wright, C. J. H. 2006. The mission of God. Unlocking the Bible's grand narrative. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

1 Hermeneutics of service delivery refers to the applicability of western theology within the context of Africa.

2 https://www.dictionary.com/browse/de

"a prefix occurring in loanwords from Latin (decide); also used to indicate privation, removal, and separation (dehumidify), negation (demerit; derange), descent (degrade; deduce), reversal (detract), intensity (decompou nd)." https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/de_

"De- is added to a verb in order to change the meaning of the verb to its opposite... De- is added to a noun in order to make it a verb referring to the removal of the thing described by the noun... removal of or from something specified... reversal of something... departure from."

3 A tentmaker is a minister serving in a congregation but obtains his income from a source other than the congregation.

4 It is not in the scope of this article to discuss the positives and the negatives of the different modes of delivery or discuss all modes of delivery.

5 A community of practice is a group of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. This understanding reflects the fundamentally social nature of human learning.