Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.119 no.3 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/119-3-1692

ARTICLES

A journal for biblical, theological and / or contextual hermeneutics?

Ernst M. Conradie

Department of Religion and Theology University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

This contribution reflects on the current sub-title of the journal Scriptura, namely "Journal for Biblical, Theological andHermeneutics ". It shows that this has been a core interest of the journal over a period of forty years. It also discusses the methodological tensions between these three forms / aspects of hermeneutics - to the point where one may wonder whether the "and" in the subtitle could be understood as "or ". It does not propose a way forward but commends Scriptura for offering the space to explore such tensions further in the South African context.

Keywords: Biblical hermeneutics; Contextual hermeneutics; Scriptura; Theological hermeneutics

On a personal note

When the first issue of Scriptura was published in 1980 I was a first-year student in the then Department of Biblical Studies of Stellenbosch University (SU). The first editor, Bernard Lategan, newly appointed at SU from the former Faculty of Theology at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), and the later editor Johann Kinghorn taught some of our modules. I was also a student in philosophy classes presented by Hennie Rossouw, one of the contributors to that first volume. His article on strategies of appropriating the meaning of the text (archaeological, analogical-typological and eschatological-critical) remains (in my view) one of the more insightful contributions ever published in this journal (Rossouw 1980a). In one way or another I have been involved in Scriptura ever since - as a student, subscriber, administrator, author, reviewer and co-editor.

In this contribution I will reflect on the history of Scriptura, not so much the history of my engagement with Scriptura but certainly the history from my perspective as an insider-outsider (given my affiliation with UWC since 1993). The current subtitle "Journal for Biblical, Theological and Contextual Hermeneutics" was only formalised in 2018. It nevertheless reflects a core concern with hermeneutics that has been evident throughout its history of forty years. I will suggest that the most interesting word in this sub-title is the word "and". This indicates the intention to hold together three forms of hermeneutics. Whether this can be maintained, is another matter. Given long-standing methodological disputes, one is inclined to wonder whether these are not held in opposition to each other, despite the journal's deliberate intention to the contrary. This is indicated in the "or" and the question mark in the title of this contribution. By reflecting on these methodological tensions I merely commend Scriptura for offering the space to explore such tensions further in the South African context.

An emerging hermeneutical awareness

When I embarked on my studies at SU in 1980 it soon became clear to me that hermeneutics, in one form or another, was a common interest of most of my lecturers, cutting across most disciplines. It took me longer to understand why. The critique of apartheid that developed amongst minorities within the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) since the 1950s coincided with disillusionment with both the way in which the Bible was read in support of apartheid and the mode of doing theology that could produce apartheid theology despite overtly maintaining an orthodox reformed approach. What went wrong? The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk. The interest in hermeneutics arises once one becomes aware of radically distorted interpretations.

One may say that the earlier 19th century debates around John Colenso and "modernity", and the early 20th century debates around Johannes du Plessis already signalled such a hermeneutical awareness (see recently Jonker 2019). One may add with Johann Kinghorn (1986:55-58) that the Du Plessis trial left a hermeneutical vacuum, a lack of competence in and sensitivity for hermeneutics in the DRC in general and in SU in particular. The teachers (some from outside Stellenbosch) who most influenced me each tackled an aspect of the hermeneutical problem. Hennie Rossouw paved the way philosophically with his formidable doctoral dissertation on the clarity of Scripture (1963) and his subsequent reading of the history of philosophical hermeneutics (e.g. 1980b). An array of biblical scholars such as Ferdinand Deist, Bernard Lategan and Bernard Combrink reread the Bible in search of adequate tools to refute Totius' conclusion that the whole Bible supports apartheid. Jaap Durand grappled with a fully historical understanding of God's economy that challenged the more static and formalised categories employed by Herman Dooyeweerd and Hendrik Stoker (see Durand 1980, Smit 2009). Willie Jonker adopted Berkouwer's understanding of correlation to propose a more dynamic constant engagement with the Word of God that cannot be captured in orthodox formulae even if they may be "true" (see Jonker 1973). Dirkie Smit took the Barthian emphasis on the Word much further through his engagement with Habermas and introduced me to David Tracy and his "revised correlation" model (Tracy 1974). David Bosch (1980) regarded missiology as the "storm centre" of theology where hermeneutical debates on relating "Christ" and "culture" are played out. He also made me aware of the possibility / danger of an inverse hermeneutics, i.e. one where the meaning of the context for (an assessment of) the text is explored (Bosch 1991:430).

When the new journal was named Scriptura, this indicated such a hermeneutical interest but also a commitment to reread the text within an ever-changing context. The journal was administratively established in a Faculty of Arts, not in a Faculty of Theology or a Seminary - which also signalled that the Bible is not only read in the church but also in the academy and indeed in society, for better but often also for worse. The Latin name Scriptura conformed to academic parlance, but it certainly also evoked the classic Protestant emphasis on sola scriptura - Scripture alone. Naming the journal thus would have made it far more church orientated. Did leaving the sola out of the name signal a protest against not only the ecclesial authorities of the day but also against the formula itself? This is for Bernard Lategan as the founder and first editor of Scriptura to answer, but I do remember him once saying that sola Scriptura is one of the most radical slogans in the history of ideas. This signalled a willingness to test an entire tradition of more than a millennium and to call for radical reinterpretation. If the pope is not infallible, neither is the synod of the Dutch Reformed Church! In fact, it may well be horribly wrong. David Tracy's distinction between the three publics of theology (academy, church and society) is as old as Scriptura and the tension between these publics remains evident in contributions to the journal (Tracy 1981). Lategan has long argued for the need for "taking the third public seriously" but also indicates how difficult that often is (see Lategan 2015).

Institutional changes over forty years

The history of Scriptura as a journal is not particularly complex but still important. In the 1980s it served as the official journal for an academic society dedicated to teaching biblical studies in schools. It later focused more broadly on religious education. Therefore, for a while one edition of Scriptura annually was dedicated to articles in this field. By the mid-1980s the Centre for Contextual Hermeneutics was established in the Faculty of Arts with Bernard Lategan as its first Director. The emphasis clearly shifted to the so-called "third public" of theology, namely "society", although this is an over-generalised rubric that encompasses government, business and industry, the media, jurisprudence and civil society alike. Lategan hosted an annual seminar on contextual Bible reading and many articles emerging from these seminars were published in the journal. In 1990 Johann Kinghorn became head of the Department of Biblical Studies in the Faculty of Arts (SU) with Bernard Lategan taking up the position of Dean of the Faculty of Arts. In 1994 the Department of Biblical Studies became the Department of Religious Studies. With Kinghorn as editor, the journal maintained its interest in hermeneutics, but the focus was no longer only on reading the text (which was still in place) but also on "reading", understanding, analysing the context - during a time of rapid transition from apartheid.

When the Department of Religious Studies was subsequently closed around 2000, the journal was almost discontinued too. Hendrik Bosman had the wisdom not to let a precious resource slip away and ensured a transition by which Scriptura would be administratively located in the Department Old Testament and New Testament at SU from 2001. Ironically, this signalled a shift away from a journal in a Faculty of Arts to a journal now housed in a Faculty of Theology. For a decade and a half Hendrik Bosman, Elna Mouton and myself served as three co-editors with Bosman being the first among equals in bearing the bulk of the administrative burden. At the time the sub-title of the journal was "International Journal of Bible, Religion and Theology". This name signalled the broad interest of the journal in seeking to hold together interests in biblical studies, theological studies and religious studies. The danger was of course that its focus was too all-inclusive and not really distinctive if compared with other journals in the field. The order of Bible, religion and theology was admittedly odd. An order of religion, sacred texts (as one dimension of religious traditions) and theological reflection on such texts would make sense - but not given the name Scriptura. A classic theological encyclopaedia would have text, tradition, doctrine, ethics and contemporary appropriation (roughly biblical studies, systematic theology and practical theology, here including mission, treating religion as an object of mission).

The name change in 2018 signalled a narrower focus on hermeneutics although this is very broadly understood. If everything is a matter of interpretation, nothing much is excluded from consideration for publication. The journal maintains its interest in the South African context despite the word "international" in the former sub-title. One may say that the earlier emphasis on international and ecumenical engagement hoped to break through the isolation associated with apartheid and the subsequent academic boycotts and to ensure subscriptions from libraries further afield. If anything, there is now a commitment to publish articles from the wider African context.

A quantitative survey

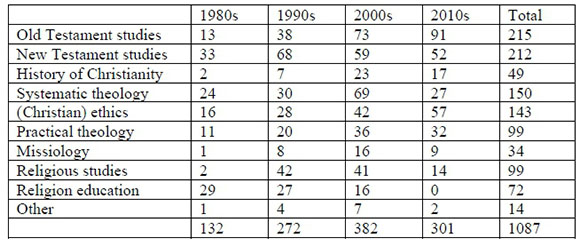

Given the comments above, it would be interesting to see what has been published in Scriptura over a period of forty years, from one decade to the next. The survey below includes only articles and special editions, not editorials, responses or book reviews. It is indeed remarkable to see the variety of genres in the first decade (conference reports, homilies, literature reviews, opinions) before the current subsidy formula inhibited such creativity. If some rather traditional subject areas are employed and if each contribution is forced into one main category (which any form of hermeneutics can hardly sustain), based mainly on the title of each contribution, the following pattern emerges:

This table indicates that the focus on hermeneutics does allow for contributions from all the traditional disciplines and sub-disciplines of the fields of religion and theology. The decrease in contributions about discourse on biblical studies as a school subject / religion / religious education since the 1990s is understandable given that the academic society that focused on this, no longer exists.

It would be quite interesting to explore demographic changes in the contributing authors in terms of nationality, institutional affiliation, gender, race, age and denominational background but this cannot be offered here. It would be even more interesting to offer a survey of themes covered and changes in the underlying theological discourse - a good topic for a postgraduate project. Suffice it to say that while the quality of the typographical layout (but not of the copy editing) in the 1980s compared to contemporary standards left much to be desired , there were some truly excellent articles over the years. These include articles by SU and UWC affiliated scholars, articles derived from seminars on contextual hermeneutics and a few by famous German theologians such as Wolfgang Huber, Eberhard Jüngel and Theo Sundermeier, to name only a few. The increase in quantity over the decades does not necessarily indicate an increase in quality, although some of the early contributions would not have been accepted according to contemporary double blind peer review processes, at least if the titles are considered (e.g. "Fundamentalism - yes or no?").

Mapping the keys to adequate interpretation

Another strategy to detect hermeneutical trends in publications in Scriptura since 1980 may be to employ forms of hermeneutics that focus on the world behind the text, the world of the text and the world in front of the text. This distinction has been widely employed by contributors to Scriptura. A few examples will suffice to illustrate this analysis.

A first attempt to map the terrain of biblical hermeneutics may be found in the textbook by Ferdinand Deist and Jasper Burden, An ABC of Biblical exegesis (1980). In an influential essay Bernard Lategan (1984) shows how two shifts occurred in New Testament hermeneutics, namely from historical critical approaches, to text-based approaches (new criticism, structural analysis), and then to contextual approaches (the role of the reader, reception theory and cultural approaches). In a widely used textbook, Dirkie Smit (1987) identified six aspects of hermeneutics, namely the world behind the text, the text itself, the role of the tradition, contemporary appropriation, ideological suspicion and the social context. Gerald West (1991) used the distinction between the world behind, of and in front of the text in various publications (early 1990s). In the first edition of Fishing for Jonah Roger Arendse, Louis Jonker, Douglas Lawrie and myself adopted and adapted Smit's analysis, identifying the same six aspects. In various contributions during the 1990s Louis Jonker argued for multi-dimensional modes of hermeneutics (see 1996). Finally, in Angling for interpretation (2001, 2008) I added a seventh set of factors namely related to the role of the contemporary rhetorical context in which a classic text such as the Bible is interpreted, and its meaning appropriated.

One may say that these attempts at mapping the terrain of biblical, theological and contextual hermeneutics are typically South African. Given our Dutch and British colonial history and our situatedness in the global South, we are influenced by discourses in continental Europe, the UK and USA, Latin America and elsewhere in Africa. Of course, the terrain of hermeneutics is contested in South Africa where the Bible is regarded as a site of struggle (Mosala 1989) and indeed an object of theft (West 2016). Admittedly, such mapping is never innocent and typically reflects a position of power. Since this is an all-male cast of mostly white scholars mapping the terrain, one needs to add that many others have contributed to the debate, not least Elna Mouton and Charlene van der Walt (see 2012) as former co-editors. The analysis will always be contested but the basic identification of three, four, six or seven sets of factors influencing biblical and theological interpretation has thus far withstood the test of time, with only some details described with different vocabularies.

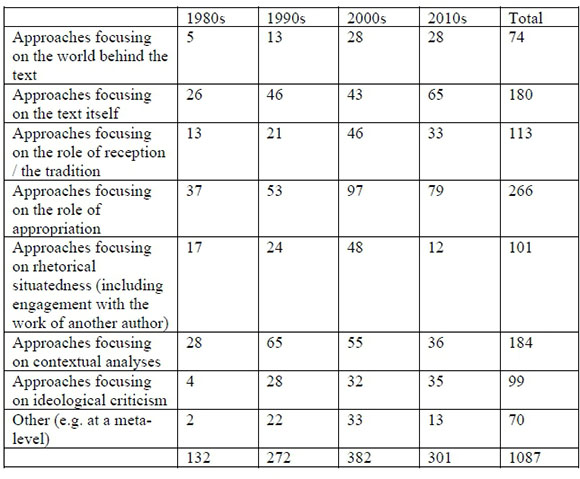

Let me on this basis again offer a statistical survey of contributions to Scriptura, now asking where the main focus of each contribution lies in terms of the seven sets of factors playing a role in biblical, theological and contextual hermeneutics as identified in Angling for interpretation. One may say that even though most scholars would acknowledge the complexity of interpretation, the key to adequate interpretation is found in different areas. Note that the focus here is not only on biblical hermeneutics, but also on theological hermeneutics (understanding the content and significance of the Christian faith) and contextual hermeneutics (arguably critically reflecting on the perceived implications of text and tradition for contemporary or future Christian praxis, for the role of religion in society or for society itself). The statistics indicated below are admittedly rather imprecise and to some extent arbitrary, but suffice to suggest that the analysis of aspects of interpretation holds:

And / or?

Hermeneutics is studied in multiple disciplines, but especially of course in philosophy, jurisprudence, literature, religion and theology. One may argue that it is hermeneutics that holds together the various sub-disciplines of Christian theology. As Dirkie Smit argues in a lesser known article (1991), the task of (evangelical) theology is to understand the Word of God anew. He observes that this entails three tasks, namely, to understand the biblical texts, to become cognisant of the tradition of interpretation and to study the contemporary context. This is a single integrated task: even though one may focus on one aspect, the others inevitably play a role, whether acknowledged as such or not. For example, biblical scholars are situated in a particular context that shapes the way they read the text. Liberation theologians and pastoral theologians alike may be concerned with particular social or personal needs, but the context is always already shaped by the biblical texts. Systematic theologians may proclaim adherence to the axiom of sola Scriptura, but their reflections are always shaped by the particular tradition in which they stand and by philosophical assumptions derived from contemporary discourse. No wonder the Methodist quadrilateral acknowledges Scripture, tradition, reason and experience as sources of Christian theology.

To recognise such a single integrated task may help to avoid the fragmentation of theological sub-disciplines. However, this cannot hide the deep methodological tensions that have emerged between theological sub-disciplines. How, then, is it possible for Scriptura to maintain the "and" in its subtitle? To have "Biblical, theological or contextual hermeneutics" as subtitle may provoke even more questions but it would at least point to the underlying problem.

One may fill volumes in explaining such tensions, but it may suffice to say that these are found between biblical studies and dogmatics, between biblical studies and ethics (see Mouton 1997 though), between the history of Christianity and systematic theology, between dogmatics and ethics, between practical theology and systematic theology, between religious studies and theological studies and between theology and a wide range of other disciplines, including the humanities, the social sciences and nowadays also the natural sciences. In working on Fishing for Jonah (and much of it in jest) I reached a half-serious ceasefire agreement with my colleagues and friends biblical scholars Douglas Lawrie and Louis Jonker. Accordingly, I may quote the Bible as a systematic theologian as long as I do not pretend to have any real clue how the text is situated in its historical context and the history of the coming into being of the text. Any quotation is also misquotation. They may study the biblical text and may spell out its contemporary significance as long as they admit that they have no real clue how to understand the doctrinal and ethical vocabulary that they employ in doing so. Any appropriation is also misappropriation.

These methodological tensions remain entrenched, as illustrated by a recent article by Izak Spangenberg. Spangenberg (2017:209) comments on the "old-fashioned use of the Bible to support specific convictions" by "most South African theologians". Inversely, he observes that "Christians project their prejudices and values onto the Bible, arguing that they are 'biblical norms and values'" (2017:212). Note the distinction here between appropriations of what the text means (for us today) and reconstructions of what the text has meant. Spangenberg is in my view right to point to the distance between the biblical texts and contemporary beliefs and values, but then seems to assume that it is possible to avoid reading the context into the text and the text into the context. He argues that those who supported apartheid on the basis of the Bible and those who rejected apartheid on the basis of the Bible followed the same strategy. However, even an atheist rejection of the relevance of the Bible for today is still a (negative) form of appropriation. His own emphasis on humanism and human rights categories operates in the same way, namely, to indicate historical distance, to question the authority of the text and to regard the Bible as one possible source of inspiration alongside many others. Elsewhere I argue that such hermeneutical keys to relate text and context cannot be avoided (see Conradie 2010). They identify / construct / enforce a point of similarity between text and context (idem-facio = to make similar). Moreover, these hermeneutical keys are typically of a doctrinal kind. This was well illustrated by an empirical project on how established Bible study groups read the Bible - in which it became clear that their doctrinal presuppositions shape their appropriation of the text (see Bosman, Conradie and Jonker 2001). I also illustrate this claim with reference to the "small dogmatics" employed as principles in the Earth Bible series (Conradie 2004). Without them, neither appropriation, misappropriation nor rejection is possible. In short, the role of doctrine (expressing deeply held convictions) cannot be avoided in exegesis. The most vehement denial of the role of doctrine may be the most doctrinal. The only way forward is to acknowledge and then discuss the relative adequacy of such doctrinal keys. Biblical and theological hermeneutics cannot be separated from each other.

The most dramatic instance where such methodological disputes surfaced in the forty years of Scriptura is in a volume of essays on New Testament ethics published as a supplement in 1992. In a concluding essay to a volume of essays on New Testament ethics, Dirkie Smit (1992:325) observes that the very sophisticated work done by his New Testament colleagues is of very little use to respond to the South African challenges of the time because they do not take into account the immense complexities involved in forming moral judgements. In particular, the distinction between ethos and ethics is not taken into account sufficiently. As a result there is a tendency to be either very vague about the contemporary significance of these texts or to jump almost directly from a particular text to a particular contemporary issue. He argues that as competent as the New Testament scholars are in analysing the texts, so superficial is their analysis of the contemporary social problems. In a scathing last sentence he comments that, with this volume of essays, we are still in the house of the deaf.

To conclude

Suffice it to say that biblical, theological and contextual hermeneutics remain in tension with each other thirty years later, as the reference to Spangenberg above illustrates. My hope is that this subtitle will serve as an acknowledgement of what David Bosch (1991:381-389) describes as a creative tension. By juxtaposing all three these modes of hermeneutics, Scriptura is signaling that the one cannot be done without the other. It also provides an academic space where this can be explored further. It is only through the collaborative efforts of authors, reviewers and readers that any distortions in the relatedness of biblical, theological and contextual hermeneutics can be recognised. May we remain vigilant in this regard in the decades to come!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bosch, DJ. 1980. Witness to the world: The Christian mission in theological perspective. Atlanta: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, DJ. 1991. Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in Theology of Mission. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Bosman, HL, Conradie, EM and Jonker, LC. 2001. Biblical interpretation in established Bible study groups: A chronicle of a regional research project, Scriptura 78:340346. [ Links ]

Conradie, EM et al. 1995. Fishing for Jonah. Various approaches to Biblical interpretation. Study Guides in Religion and Theology 1. Bellville: UWC Publications. [ Links ]

Conradie, EM. 2004. Towards an ecological biblical hermeneutics: A review essay on the Earth Bible project, Scriptura 85:123-135. [ Links ]

Conradie, EM. 2008. Angling for interpretation: A first guide to Biblical, theological and contextual hermeneutics. Study Guides in Religion and Theology 13. Stellenbosch: SUN Press. [ Links ]

Conradie, EM. 2010. What on earth is an ecological hermeneutics? Some broad parameters. In Horrell, DG et al. (eds), Ecological hermeneutics: Biblical, historical, and theological perspectives. London: T & T Clark, 295-314. [ Links ]

Deist, FE and Burden, JJ. 1980. An ABC of Biblical exegesis. Pretoria: JL van Schaik. [ Links ]

Durand, JJF. 1980. God in history: An unresolved problem. In Kõnig, A and Keane, MH (eds), The meaning of history. Pretoria: Unisa, 171-178. [ Links ]

Jonker, LC. 1996. Exclusivity and variety: Perspectives on multidimensional exegesis. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Jonker, LC and Lawrie, DG (eds). 2005. Fishing for Jonah (anew): Various approaches to Biblical interpretation. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. [ Links ]

Jonker, LC. 2019. Herinnering en verlange: Gesprekke oor mag, geskiedenis en die Bybel. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. [ Links ]

Jonker, WD. 1973. Dogmatiek en Heilige Skrif. In Bakker, JT et al. (eds), Septuagesimo anno - Theologische opstelle aangeboden aan Prof. Dr. G. C. Berkouwer,. Kampen: JH Kok, 86-111. [ Links ]

Kinghorn, J (ed.). 1986. Die NG Kerk en apartheid. Johannesburg: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Lategan, BC. 1984. Current issues in the hermeneutical debate, Neotestamentica 18:117. [ Links ]

Lategan, BC. 2015. On taking the third public seriously. In DJ Smit (ed.), Hermeneutics and social transformation. Stellenbosch: Sun Press, 149-158. [ Links ]

Mosala, IJ. 1989. Biblical hermeneutics and black theology in South Africa. Grand Rapids: WB Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Mouton, E. 1997. The (trans)formative potential of the Bible as resource for Christian ethos and ethics, Scriptura 62:245-257. [ Links ]

Rossouw, HW. 1963. Klaarheid en interpretasie: Enkele probleemhistoriese gesigspunte in verband met die leer van die duidelikheid van die Heilige Skrif. Amsterdam: Jacob van Campen. [ Links ]

Rossouw, HW. 1980a. Hoe moet 'n mens die Bybel lees? Die hermeneutiese probleem, Scriptura 1:7-28. [ Links ]

Rossouw, HW. 1980b. Wetenskap, interpretasie, wysheid. Port Elizabeth: University of Port Elizabeth. [ Links ]

Smit, DJ. 1987. Hoe verstaan ons wat ons lees? Kaapstad: NG Kerk-Uitgewers. [ Links ]

Smit, DJ. 1991. The challenge of theological studies for evangelical students, Apologia 6(2):48-57. [ Links ]

Smit, DJ. 1992. Oor 'n Nuwe Testamentiese etiek, die Christelike lewe en Suid-Afrika vandag. In Lategan, BC and Breytenbach, C (eds), Geloof en opdrag: Perspektiewe op die etiek van die Nuwe Testament, Scriptura S9: 303-325. [ Links ]

Smit, DJ. 2009. In die geskiedenis ingegaan. In Conradie, EM en Lombard, C (eds), Discerning God's justice in church, society and academy: Festschrift for Jaap Durand. Stellenbosch: SUN Press, 131-166. [ Links ]

Spangenberg, IJJ. 2017. Is God a ventriloquist and is the Bible God's dummy? Critical reflections on the use of the Bible as a warrant for doctrines, policies and moral values, Scriptura 116:208-223. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, C. 2012. Close encounters: Creating a safe space for intercultural Bible reading, Scriptura 109:110-118. [ Links ]

West, GO. 1991. Biblical hermeneutics of liberation. Modes of reading the Bible in the South African context. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

West, GO. 2016. The stolen Bible: From tool of Imperialism to African icon. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]