Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.118 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/118-1-1432

ARTICLES

The water of life: Three explorations into water imagery in revelation and the Fourth Gospel

Mark Wilson

Old and New Testament, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

This article is comprised of three separate yet related explorations regarding the image of water in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel. It first explores the attempt to tabulate examples of water terminology in the New Testament and how that tabulation has proven incomplete. A fresh assessment is provided that includes an expanded lexical domain for water and notes its high frequency of usage in Revelation and John when compared to the rest of the New Testament. The next section examines four pericopae in Revelation and in the Fourth Gospel where water imagery is prevalent. Old Testament backgrounds for language are examined along with the intertextual relationship between texts in Revelation and John. A theological understanding of water imagery for Revelation and the gospel is proposed. In the final section, the Asian cultic practice of using water-the hydrophoros in the Artemis cult-is presented. While a Jewish background is commonly posited as the background for understanding water imagery in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel, the Greco-Roman polytheistic cults are posited as the primary religious background for Gentile believers in the Asian congregations.

Key words: Water Imagery; Revelation; Fourth Gospel; Patmos; Artemis; hydrophoros

Introduction1

Water is recognised as a significant trope in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel. The metaphor has been explored in numerous monographs, articles, and commentaries. This article seeks to add three further dimensions to that discussion. The first exploration seeks to elucidate the full extent of the semantic domain of water in the New Testament, especially in Revelation and the Gospel of John. The second examines four significant pericopae both in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel. It initially explores their intertextual relationship with Old Testament texts and then intra-textually, particularly through a lexical comparison. It then draws conclusions about how water imagery is used theologically in each document. The third exploration begins by noting that a background in Jewish texts and ritual is the lens usually offered to explain how water imagery was interpreted by the first audience. However, what is seldom identified and addressed is the interpretive grid according to which the Gentile believers from a pagan background might have understood such water imagery. A Greco-Roman cultic practice-the hydrophoros in the Artemis cult-is suggested as a possible pagan background for water imagery that would have been familiar to Gentile Christians in Ephesus and the rest of the seven churches.

Exploration 1: Water terminology in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel

In a recent monograph on water imagery, Crutcher (2015:1) writes, "Water is a powerful and pervasive image in the Hebrew Scriptures and other ancient Jewish literature.... Many of these water images from the Hebrew Scriptures are reused by the writers of the New Testament, particularly in the Gospels and the book of Revelation." Goppelt (1983:314-7) notes three basic categories into which references to water fall in literature of the ancient Orient and Greco-Roman world: 1) flood stories (e.g. Gilgamesh Epic); 2) life sources (e.g. rivers, lakes, springs, etc.); and 3) purification sources (e.g. fountains, basins, mikvoth, etc.). Crutcher (2015:3) observes that the Fourth Gospel has more references to water (28) than any other New Testament book except Revelation (38). She writes, "The Johannine writings combined (Gospel [of John], 1 John, Revelation) account for 70 instances of these water terms, over half the total in the New Testament" (i.e. 118).2 However, her statistics are confined to only five terms: ύδωρ (water), λίμνη (lake), κολυμβήθρα (pool), πηγή (spring or well),3 and ποταμός (river). A review of the domain "Bodies of Water" (1.J) in Louw and Nida (1998:s.v.) indicates that four other terms are missing: πέλαγος (open sea), βυθός (deep water), χείμαρρος (brook or wadi), and θάλασσα (sea). Of these, θάλασσα is the most significant with 91 occurrences in the New Testament, of which two are in the Gospel of John and 26 in Revelation. The chart below summarises the NT usage of these nine water-related terms. The total number of water terms-210-is 78% more than Crutcher's total of 118. Of these 210, 92 are found in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel. Rather than numbering 59% of New Testament occurrences as per Crutcher, these terms comprise around 44% of the total.

These results present a much more comprehensive treatment of water terms in the New Testament, especially in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel. They also function as a corrective for future researchers who would use Crutcher as a source for data on water vocabulary, particularly for these two books.

Water was particularly important for life in the cities of the Greek East, especially of Roman Asia. Three of the seven churches-Ephesus, Smyrna, and Pergamum (via nearby Elaia)-were ports on the Aegean; the other four were on or near rivers- Thyatira (Lycus), Sardis (Hermus), Philadelphia (Cogamus), and Laodicea (Lycus/Meander). Most had fresh water delivered via aqueducts or siphon systems. Water therefore provided various benefits- economic (commerce), aesthetic (fountains), sanitary (baths and sewer systems), and domestic (potability)-to these cities.

Exploration 2: Water imagery in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel5

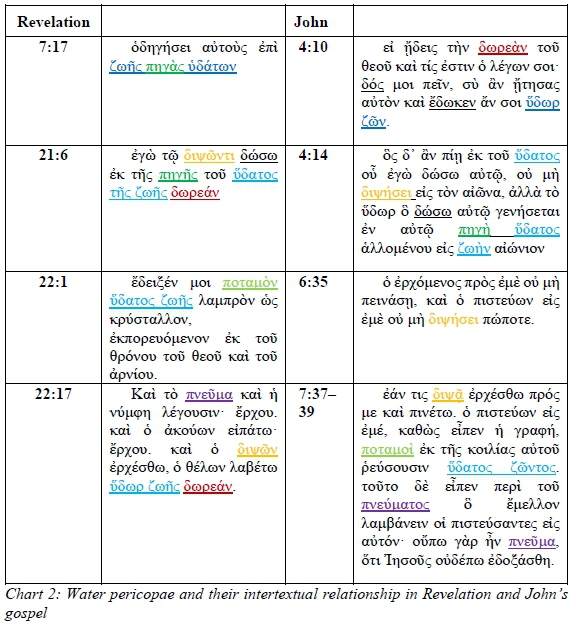

In this second exploration, water imagery in Revelation will first be investigated in four pericopae followed by a similar investigation of four pericopae in John's gospel. A chart showing the Greek text of these related pericopae, particularly the intertextual relationship of their vocabulary, is presented.

John's exile on Patmos for an indeterminate period appears to have influenced some of the imagery in his apocalyptic visions.6 Surrounded by water during his exile, the sea (θάλασσα) is a dominant image in Revelation with 26 references. For John, sea is a metaphor for heavenly splendour (4:6; 15:2), the realm of God's creation (5:13; 10:6), a place for judgment (7:1-3; 8:8-9), the abode of the first beast (13:1), a domain of commerce (18:17, 19), the holding place for souls (20:13), and a lacuna in the new heaven and earth (21:1).7 Islands are mentioned at the opening of the sixth seal (6:14), and at the outpouring of the seventh bowl, every island will disappear (16:20). These random, general references to water found throughout Revelation, however, give way to four particular pericopae where water is used metaphorically in a significant way. While these offer similar language and imagery, they are presented in varying contexts.

Pericope 1: Revelation 7:17

Rev. 7:17 portrays the proleptic fulfilment of several covenant promises to the great multitude gathered around the heavenly throne in heaven. These are the victors who have emerged successfully from the great tribulation and are receiving their promised rewards. Hunger, thirst, physical discomfort, and sorrow give way to spiritual provision from the Lamb who will shepherd and guide them. His guidance will lead them to springs of the water of life.8

The use of this word cluster in the Old Testament is limited but striking. Ps. 113:8 LXX alludes to Israel in the wilderness when God turned the stone into a pool of water (λίμνας υδάτων) and the flintstone into a spring of water (πηγάς υδάτων).9 The psalmist refers back to Deut. 8:15 where identical language is used (έκ πέτρας άκροτόμου πηγην ύδατος).10 One of God's complaints with Judah prior to the Babylonian captivity was that she had forsaken the spring of the water of life (πηγην ύδατος ζωής; Jer. 2:13; cf. 17:13: ύδωρ ζων έξ Ιερουσαλήμ).11 In this verse God specifically identifies himself as that source of life. However, the closest intertextual reference for Rev. 7:17 is Isa. 49:10 where Isaiah prophesies that at Israel's restoration the captives will neither hunger nor thirst (ού πεινάσουσιν ουδέ διψήσουσιν) and that God will lead them to springs of water (διά πηγων υδάτων άξει αύτούς). Like Isaiah, John casts the fulfillment of this promise in the future. However, rather than an earthly fulfillment for Israel, for the followers of the Lamb, its fulfillment will be in New Jerusalem. Goppelt (1983:325) observes, "While the dwellers on earth (8:13; 11:10, etc.) are deprived of necessary water, those redeemed from the earth (14:13) are given the water of life to drink in the consummation."12

Pericope 2: Revelation 21:6

The proleptic promise given in 7:17 is reiterated in 21:6: "I will let the thirsty drink freely from the spring of the water of life."13 This is a final victor saying similar to those found at the conclusion of the prophetic messages to the seven churches in chapters 2 and 3.14Swete (1911:281) calls this "an eighth promise that completes and in effect embraces the rest".15 As I (Wilson 2007a:174; cf. 175-9) have written elsewhere, "The seven letters do not contain an explicit promise of living water, which is here given to the victor who thirsts for God. This promise is repeated under the image of inheritance as God's son in verse 7." Thus, according to Beckwith (1919:752), "the thirst for God will be satisfied in the relation of perfect sonship with God". Mealy (1992:263) identifies the thirst here as "not so much a symbol of their desire for God as it is emblematic of their weary condition which is the result of earthly faithfulness" (italics his). Yet it is surely the victors' desire to follow the Lamb that sustains them through persecution by the two beasts and the earth's inhabitants (cf. Matt. 5:6).

Commentators suggest various interpretations for this promise. Smalley (2005:541), while noting that running water may suggest a baptismal setting and citing Didache 7:12, nevertheless opts for a spiritual meaning; that it represents the "salvific presence of God through faith in the redeeming Lamb". For him the metaphor is soteriological. However, Thomas and Macchia (2016:174), referring to 7:17 and drawing co-texts from the Fourth Gospel, suggest: "This potent description calls to mind both the guiding activity of the Spirit of Truth (John 16:13) and the emphasis placed upon wells of living water in John's gospel (4:14; 7:38), again reminding hearers of the intimate relationship that exists between Jesus and the Spirit in Revelation." For them, the metaphor of the water of life is pneumatological.

Pericope 3: Revelation 22:1

The springs of water promised in 21:6 are transformed into a river in 22:1: "Then he showed me a river of the water of life shining like crystal and coming out of the throne of God and of the Lamb."16 Two prophetic pictures of flowing water suggest an Old Testament background for John's description.17 Ezekiel saw water coming from beneath the threshold of the temple and flowing southward (Ezek. 47:1-2). As the river deepened, Ezekiel saw trees growing along its banks. The significance of these fruit trees is then described: "Their leaves will not wither, nor will their fruit fail. Every month they will bear fruit, because the water from the sanctuary flows to them. Their fruit will serve for food and their leaves for healing" (Ezek. 47:12). Later, the prophet Zechariah foresaw a similar day of the Lord in the future when living water (ύδωρ ζών) would flow from Jerusalem (Zech. 14:8). These prophetic pictures, like John's, also recall the river in the Garden of Eden that watered all the trees including the tree of life. As the river flowed from the garden, it split into four branches to water the earth (Gen. 2:9-10).

Regarding this image, Beale (1999:1104-5) notes that "water also symbolized the Spirit in the OT, Jewish writings, and elsewhere in the NT". Smalley (2005:562) further notes: "The concept of 'living water', denoting the eternal, spiritual vitality which flows from God in Christ and through the Spirit, is used in the New Testament solely by the writers of John's Revelation and the Gospel." This picture of the water flowing from the heavenly throne shared jointly by God and the Lamb perhaps inspired the early Church Fathers to form their creedal statement that the Holy Spirit proceeds both from the Father and the Son, the Filioque.18

Pericope 4: Revelation 22:17

The promise of 21:6 is repeated in "compressed form"19 in 22:17: "Whoever thirsts, let them come. And whoever desires, let them receive the water of life freely." The invitation is extended to the nations (21:24, 26; 22:2) like the similar invitation in Isa. 55:1: "Whoever thirsts, come to the water" (οί δνψωντες πορεύεσθε έφ' ύδωρ).20 The Spirit is mentioned in each of the hearing sayings in Rev. 2-3: "Let everyone who has an ear hear what the Spirit is saying to the churches."21 At the beginning of 22:17 the Spirit also speaks in a modified hearing saying: "The Spirit and the Bride say, 'Come!' Whoever hears, let them say, 'Come'." The promise is part of a threefold invitation to "Come" uttered by the Spirit and the Bride (also 22:20). Peterson (1988:194) succinctly connects these images: "The Spirit, the Bride, and the listeners all urge this arrival 'Come.' The thirsty of the world are invited to come to him who comes."22 Remarkably, in Revelation's final chapter believers in the seven churches still equivocating are again appealed to strongly. For the Laodiceans who were spiritually lukewarm and did not realise it (3:16), "this final promise to quench their thirst would have been especially significant" (Wilson 2007b:133).

Koester (2015:857) notes that some commentators understand this invitation to mean that the audience receives the water of life now in this present life. However, this interpretation better fits the "realised"23 or "present" 24 eschatology of the Fourth Gospel. For in Revelation the promise of the water of life is a future one realised in New Jerusalem. Nevertheless, Beale views these concluding imperatives as possible references to both the present age and the future age, finding a precedent for this in 7:17. He writes: "When believers successfully finish their life of faith, they are rewarded at death with 'the water of life.' This blessing is an anticipation of the full reward at the end when the 'full number' in the church finally overcome" (Beale 1999:1150). Since the other promises to the victors are all fulfilled in the future, it seems unlikely that one would be partially fulfilled at the death of the believer.

In 22:17 Lee (2014:90) sees the author depicting the Spirit "as an evangelist or missionary". Curiously, he interprets this invitation of grace for salvation as an address to nonbelievers: "Thus, the narrator, as an evangelist who invites nonbelievers on earth to receive the gospel, describes the Spirit." Yet, like earlier pericopae using this imagery, it is expressly addressed to believers in the churches (22:16) who are part of the Bride (22:17). Rea (1990:347) insightfully captures the relationship of water to this final reference to the Spirit in Revelation: "God's perpetual giving of Himself in His Spirit will be an ever-flowing river."

These four water pericopae in Revelation all include eschatological promises mediated by the Holy Spirit, hence they are pneumatological as well. The victors in the seven churches of Asia are characterised as the thirsty who will be rewarded in the future. Their travails and persecutions in the present life by Jezebel, the two beasts, and the great whore/city, will be assuaged by Jesus through the Spirit at the wedding supper of the Lamb in New Jerusalem. Thus, the metaphor of water is predominantly eschatological in Revelation with the Spirit as the eternal life-source in the new heaven and new earth.

In the second half of Exploration 2, water imagery in the Fourth Gospel will be investigated. Numerous monographs and articles have been written about the subject; therefore this will be a modest attempt to contribute a fresh reading. In the Fourth Gospel the motif of water, according to Smalley (1998:132) becomes an "apparent preoccupation".25 This is first seen in the miracle at Cana (2:6-11) and in the conversation with Nicodemus (3:5), where water assumes a spiritual meaning. If the chronological priority of Revelation is accepted (see note 7), water imagery established in the Apocalypse is recast as historical narrative in John's gospel during several key scenes in Jesus' ministry.26 This imagery utilises vocabulary similar to that in Revelation (see chart 2). The source of the water in both is either a spring (πηγή) or river (ποταμός). Nevertheless, there are a couple of anomalies. The genitival form ζωής in Revelation becomes the present participle of ζάω in John 4:10 and 7:38. δωρεάν is used adverbially in Rev. 21:6 and 22:17 while it becomes an accusative noun in John 4:10. Four texts related to water refer specifically to the Spirit, so observations will be limited to these.

Text 1: John 4:10

Two texts are found in the pericope related to the Samaritan woman. John 4:10 reads: "If you knew the gift of God and who it is that asks you for a drink, you would have asked him and he would have given you living water."27 The word δωρεά occurs only here in the gospels. As Westcott (1889:69) notes, "It carries with it something of the idea of bounty, honour, privilege; and is used of the gift of the Spirit (Acts ii.38, viii.20, x.45, xi.17)." Beasley-Murray (1999:60) emphasises the spiritual meaning of this metaphor: "It is evident that 'living water' has a variety of nuances that must be taken into account; chiefly it appears to denote the life mediated by the Spirit sent from the (crucified and exalted) Revealer-Redeemer" (italics his).28 Bruce (1983:104) writes similarly, "Here the water in Jacob's well, symbolizing the old order inherited by Samaritans and Jews alike, is contrasted with the new order, the gift of the Spirit, life eternal." This accords with one of the symbolic meanings for water in early Judaism found in the rabbinical Targum of Isa. 44:3: "As water is given to dry land and is led over arid land, so will I give my Holy Spirit to your son and my blessings to your children's children." The pneumatological dimension of the metaphor of water seen in Revelation is likewise seen in the Fourth Gospel.

Text 2: John 4:14

Four verses later in 4:14 Jesus tells the Samaritan woman that if she or others drink water from Jacob's well, they will thirst again: "But whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life."29 The thirst of which Jesus speaks, is spiritual, not physical, hence, the quenching of this thirst requires the supernatural action of the Holy Spirit. For as Koester (2003:191) writes, "If Jesus is both Messiah and Savior of the world, the living water is both revelation and the Spirit."30 Bruce (1983:105) observes insightfully that the evangelist may provide the same narrative aside here as he gives in 7:39: "For the Spirit of God, imparted by our Lord to his people, dwells within them as a perennial wellspring of refreshment and life." In summary Jones (1997:113) notes: "When viewed from the perspective of the Gospel as a whole, however, it appears that the narrator here begins to prepare the reader to unite all the various images and meanings of water under the general heading of the pre-eminent gift of the Spirit." Thus the interpretation of this image is stable.

Text 3: John 6:35

Jesus directs the next water image to a Jewish crowd that followed him in boats from Tiberias to Capernaum (John 6:22-25). To their request for a sign, he offers to show them a heavenly one like the manna given to Moses: The Father will send the true bread from heaven. The Jews then request that they be given this bread. In reply Jesus utters the first of the seven "I am" sayings: "I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never go hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty" (6:35). Although water is not explicitly mentioned here, it is certainly implied. For the idea of this verse is very close to John 4:14 as well as Rev. 21:6.31 But, unlike Revelation, the satisfaction of spiritual hunger and thirst is soteriological, not eschatological, for belief in the Son brings eternal life (John 6:40).

Text 4: John 7:37-38

The final text with a water image is 7:37-38. Jesus was in Jerusalem for the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot), a festival connected with water and light. The water-pouring ceremony32 at tabernacles was related in later rabbinical sources to the promised outpouring of the Holy Spirit. For example, Sukkãh 55 a, citing Jehoshua ben Levi, says, "Why did they call it (the court of women) the place of drawing water? Because it was from there that they drew the Holy Spirit, according to the word: 'With joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation'."(cf. Isa. 12:3)33

On the last day of the feast, Jesus stood and cried out, "Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them" (7:37-38).34 Gates Brown (2003:155) notes that these words, particularly their source, "have occasioned voluminous analysis by biblical scholars". Smalley (2005:562) notes that even if the source of the water of life is ambiguous-believer or Christ-"in either case the water symbolises the Spirit (7.39); and, according to the Fourth Gospel, the Spirit is the gift of both Jesus and the Father". Gates Brown (2003:165) further notes regarding Jesus' audience: "In contrast to those who pledge their allegiance to Moses and await a future reiteration of his water miracles, those who remain loyal to Jesus are promised 'rivers of living water' in the present age, an outpouring of spirit." This living water is the Spirit communicated by Jesus. Gates Brown (2003:179) adds, "Moreover, for the identification of 'living water' as the Spirit we have the specific evidence of John vii 37-39."

The living water thus promised in 7:38 is realised in 20:22 when Jesus breathes upon his disciples to receive the Holy Spirit. This is made clear by the narrator's aside in 7:39: "By this he meant the Spirit, whom those who believed in him were later to receive. Up to that time the Spirit had not been given, since Jesus had not yet been glorified."35Brown (1966: 328) likewise connects these verses: "If the water is a symbol of the revelation that Jesus gives to those who believe in him, it is also a symbol of the Spirit that the resurrected Jesus will give, as v. 39 specifies."36 From John's perspective, only after Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection, could the Spirit be given to believers (cf. 1 John 5:7-8). Thus, as Comfort and Hawley (1994:132) conclude, "once Christ became the life-giving Spirit through resurrection (see 1 Cor. 15:45; 2 Cor. 2:17-18), he could be received as the living water".

Despite such strong characterisations, Ng (2001:161) in her study of water symbolism in John, concludes that water always symbolises something eschatological. She (2001:95) contends that "it is only with eschatology that water symbolism in John continually interacts".37 Yet that eschatology was a realised one for John's audience with the promised living water to be given after Jesus' resurrection. Jones (1997:229-30) concludes his investigation of water in the Fourth Gospel by stating, "Primarily, water symbolizes the Spirit". Taken by itself, the statement is starkly unnuanced, despite the numerous examples offered to support his assertion. However, in the next paragraph he observes that, "water symbolizes Jesus himself", who is the "primary symbol in the Fourth Gospel". Water is thus a recurring symbol "that points to him and renders him present". Jones seems to be speaking in circles. The bottom line is that Jesus as the living water mediates that water to those who believe in him through the Holy Spirit.38 Koester (2003:176) expresses this well in conclusion: "If living water is the revelation Jesus offered people during his ministry, this revelation is extended through the Spirit to readers living after Jesus' departure to the Father."

Summarising this second exploration, the author of the Fourth Gospel seemingly draws on Revelation's water imagery, which itself is drawn from Jewish Scripture and ritual. He recontextualises it by using similar language and phraseology but with a different theological focus. A comparison of water-related texts in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel has revealed that in the former the Spirit is primarily eschatological, while in the latter the Spirit is primarily soteriological. The thirsty in Revelation are believers, while those who thirst in John are unbelievers.39

Exploration 3: Hydrophoroi in Patmos and Asia

John's arrival on Patmos in the late 60s brought him in contact with an active Artemis cult somewhat different from that in nearby Ephesus. Patmos was not the barren island used only as a penal colony as sometimes depicted by commentators (cf. Mounce 1997:75). Instead it had a small but active military garrison, a resident population who had lived there for centuries, and active religious cults including a temple of Artemis.40While on Patmos, John undoubtedly gained local information regarding Artemis Patmia, the patron goddess of the island. An inscription found at her temple site-where the Monastery of St. John in Chora, founded in 1088, is now situated-provides important information about the cult's origin and practice on "the loveliest island of the daughter of Leto".41 First, it alludes to a foundation myth that Artemis was brought from Scythia by Orestes, the son of Agamemnon, to remove his terrible madness resulting from the murder of his mother. The Patmian version of the Orestes myth differs from that of Euripides: Orestes overcame his crime by recovering a sacred statue of Artemis in Tauria believed to have fallen from heaven. Boxall (2013:233) concludes, "The Patmos inscription apparently claims that this sacred statue was brought, not to Athens, but to Artemis' own island of Patmos."42 Second, the inscription names Vera, a maiden priestess appointed by the Virgin Huntress herself. She was born on Patmos but raised on Artis (Argos?) and crossed the stormy Aegean to return home to sacrifice goats on the altar of Artemis Patmia. Afterwards she organised a festive celebration and banquet. Vera also held the honorific title of υδροφόρος (water-bearer).43

Among the honorific titles found in Greek inscriptions during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, particularly in western Asia Minor, hydrophoroi presents itself as one of the most interesting.44 Artemis, as the initiatory goddess of virgins, supplied the majority of adolescent priestesses including the hydrophoroi for service in cult worship.45 Connelly (2007:40) notes that "the office of hydrophoros was also the top job for maidens".This view is sustained when figures depicting a hydrophoros are examined. Various museums contain terracotta figurines of a female with her right arm raised to support the hydria on her head. The earliest of these objects date from the 5th to the 2ndcenturies BCE and come from various cities such as Knidos, Tralles, and Rhodes.46 One figurine, now in the Harvard Museum, is possibly Roman and dates to the 1st century BCE to 1st century CE.47 One well-known epigram, dated to the 2nd century CE, comes from Patmos. It states that Artemis herself made "Kydonia, the daughter of Glaukies, priestess and hydrophoros... to offer minor sacrifices" (Merkelbach and Stauber 1998:169-70G). The office of hydrophoroi in the imperial period is known particularly from nearby Miletus, which was the neokoros for the oracle temple of Apollo at nearby Didyma. Water from a sacred spring was the source of inspiration (Parke 1985:213-4). Its sister temple of Artemis had five wells or springs within its temenos (sacred precinct). This abundance of water suggests a connection with her primary priestess, the hydrophoros. 84 inscriptions at Didyma honour hydrophoroi (Ibid. 307-88).

The Greek Dodecanese islands were once part of Roman Asia, and Patmos was historically attached to Miletus, one of the province's conventus, or juridical assize, cities. Inscriptions from Didyma suggest that the father of the hydrophoros held the office of προφήτης (prophet) simultaneously (Bremmer 1999:190).48 In an extensive study on the term, Heller (2017:18) found that the preponderance of such commemorative inscriptions49 were concentrated at Didyma, with 38 prophetai (100% male) and 15 hydrophoroi (100% female) identified. Regarding the identifiable civic affiliations of these 15, three were Greek citizens while nine were Roman citizens (Heller 2017:3-8, especially tables 1.1; 1.2a, b, 1.3.a). Nevertheless, the title hydrophoros is also found in inscriptions from other Ionian cities like Miletus, Ephesus, and Smyrna. 26 dedications mentioning the name, family background, and benefactions date from the Hellenistic period, while 87 date to the first three centuries CE (Connelly 2007:40).

What was the function of a hydrophoros? While her activities are not known exactly, inferences can be drawn from inscriptional evidence. I.Didyma 331 (1st-2nd century CE) mentions a hydrophoros named Sympherousa, a daughter of Apellas, who religiously performed all the prescribed sacrifices and libations and the rites of the mysteries for the goddess Artemis Pythia (Schuddeboom 2009:218 no. 41). But, as Graf (2003:247) writes, "We lack the means to determine whether this too was a specific initiation of a hydrophoros, or whether she had also to preside over mystery rites that were open to some visitors of the oracle." In addition to hosting feasts and making sacrifices, she would have offered libations before the altars.50 Fontenrose (1998:126, esp. note 5) muses about the special functions related to the hydrophoros in the cult of Artemis Pythia: "We have noticed the several springs, wells, or fountains in Artemis' sanctuary. The hydrophor might have had to carry water in the mysteries of Artemis, or perhaps in all her rites and perhaps those of other Didymean deities." Fontenrose (1998:127-8) further observes, "The prevalence of these titles (e.g., hydrophoros and loutrophoros) in cults of Artemis on the east Aegean coast, as well as the several fountains in Artemis Pythie's temenos at Didyma, points to an association of the Asian Artemis with water."

Among commentators on Revelation or John only one has been found who refers to the Patmos inscription. Page (2014:chap. 18 n.p.) attempts to contextualise the Patmian Artemis for his interpretation of Rev. 12:15-16 and thus links the Patmian hydrophoros Vera and her duty of pouring out water to "the water gushing from the dragon's mouth and disappearing into the earth". However, this interpretation is unconvincing, and Page never connects the hydrophoros inscription to any other texts in Revelation that mention water.

Concluding remarks

The three explorations in this study have focused on the importance of water for the early believers in Asia. Existentially, water was essential, not only for domestic use, but also for commerce, sanitation, and architecture in the cities in which they lived. Yet water also became an important spiritual symbol related to their new life in Christ. One final observation should be made regarding these explorations. Water imagery in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel is usually interpreted from a Jewish background. For example, Crutcher (2015:15) states that her study relates "specifically to one particular recurring image (i.e., water) of Yahweh's creative and sovereign powers in the Jewish mindset of the Second Temple period". Her interest therefore is to examine "links between the New Testament passages and Old Testament precursors". Yet the provenance of the Fourth Gospel is usually not situated in Palestine,51 but in and around Ephesus (cf. Irenaeus Haer. 3.1.2), the same region as the seven churches of Revelation (cf. Smalley 1998:186).52 So the audience would have included many Gentiles without a background in Jewish texts and religious practices.53

Interpreters of Revelation and the Fourth Gospel have probed their author's use of the Jewish Scriptures.54 Koester (2015:123) even asserts about the audience of Revelation: "John assumed that his readers would be acquainted with biblical narratives and prophetic texts." Yet can such an assumption be sustained, particularly among Gentiles new to faith? Stanley (2008:142) observes, "Christians from non-Jewish backgrounds-the great majority by the time the New Testament texts were written- frequently entered the church with no idea of where to look for the biblical verses cited by Paul and other early Christian writers."55 It would have been the Jewish believers or Gentile God-fearers,56 aware of the rich intertextuality in these texts, who could explain these quotations and allusions to such Gentile believers and to the "unlearned" in the meetings (1 Cor. 14:23-24).57

Koester (2015:123) does allow that John's audience would also have been familiar "with stories from their Greco-Roman cultural context. As Revelation was read aloud, people would have heard expressions and themes that they knew from other settings." Fee (1987: 147) makes a significant observation about the pre-Christian Corinthians (άπιστοι; 1 Cor. 14:23): "As practicing pagans most of them would have frequented the many pagan temples and shrines (naoi) in their city." Thus they would likely have been familiar with various religious rites such as those surrounding the hydrophoros. Writing from Ephesus, Paul observed regarding the religious background of the Gentile believers: "You know that when you were pagans, you were enticed and led astray to idols that could not speak" (1 Cor. 12:2 NRSV).58 This was therefore their initial contextual background for water imagery and prophetic activity, subsequently encountered in Revelation and the Fourth Gospel as believers. For them the prophetic spirit that previously issued from water in the hydrophoros ritual, was now re-visioned as the Spirit of prophecy from whom proceeded the water of life.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abasciano, B.J. 2007. Diamonds in the rough: A reply to Christopher Stanley concerning the reader competency of Paul's original audiences, Novum Testamentum 49(2):153-183. [ Links ]

Barrett, C.K. 1947. The Old Testament in the fourth gospel, Journal of Theological Studies 4(191/92):155-169. [ Links ]

Barrett, C.K. 1978. The gospel according to John, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox. [ Links ]

Beale, G.K. 1998. John's use of the Old Testament in Revelation. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Beale, G.K. 1999. The book of Revelation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Beasley-Murray, G.R. 1978, Revelation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Beasley-Murray, G.R. 1999, John, 2nd ed. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. [ Links ]

Beckwith, I.T. 1919. The Apocalypse of John. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Boxall, I. 2013. Patmos in the reception history of the Apocalypse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bremmer, J.N. 1999. Transvestite Dionysos. In M.W. Padilla (ed.), Rites of passage in ancient Greece: Literature, religion, society. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, pp. 183-200. [ Links ]

Bremmer, J.N. 2008. Priestly personnel of the Ephesian Artemision: Anatolian, Persian, Greek and Roman aspects. In B. Dignas and K. Trampedach (eds), Practitioners of the divine: Greek priests and religious officials from Homer to Heliodorus. Cambridge, MA: Center for Hellenic Studies, pp. 37-53. [ Links ]

Brown, R.E. 1966. The gospel according to John I-XII. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Bruce, F.F. 1983. The gospel of John. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Burge, G. 1987. The anointed community: The Holy Spirit in the Johannine tradition. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Carter, W. 2008. John and empire, initial explorations. New York: T& T Clark. [ Links ]

Ciampa, R.E. and Rosner, B.S. 2010. The first letter to the Corinthians. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Comfort, P.W. and Hawley, W.C. 1994. Opening the gospel of John. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House. [ Links ]

Connelly, J.B. 2007. Portrait of a priestess: Women and ritual in ancient Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Craigie, P.C., Kelley, P.H. and Drinkard, J.F. 1988. Jeremiah 1-25. Dallas: Word. [ Links ]

Crutcher, R.G. 2015. That he might be revealed: Water imagery and the identity of Jesus in the gospel of John. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Eisenstein, J.D. 1906. Water-drawing, Feast of . ln I. Singer (ed.), Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 12. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, pp. 476-477. [ Links ]

Fee, G.D. 1987. 1 Corinthians. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Fekkes, J. 1994. Isaiah and prophetic traditions in the book of Revelation. Sheffield: JSOT Press. [ Links ]

Fontenrose, J. 1998. Didyma: Apollo's oracle, cult, and companions. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Gates Brown, T.G. 2003. Spirit in the writings of John. London: T &T Clark. [ Links ]

Goppelt, L. 1983. ύδωρ. In G.W. Bromiley (ed.), Theological dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 8. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 314-333. [ Links ]

Graf, F. 2003. Lesser mysteries - not less mysterious. In M.B. Cosmopoulos (ed.), Greek mysteries: The archaeology and ritual of ancient Greek secret cults. London/New York: Routledge, pp. 242-262. [ Links ]

Guérin, V. 1856. Description de l'ile de Patmos et de l'ile de Samos. Paris: Durand. [ Links ]

Heller, A. 2017. Priesthoods and civic ideology: Honorific titles for Hiereis and Archiereis in Roman Asia Minor. In E.M. Grijalvo, J.M.C. Copete and F.L. Gomez (eds), Empire and religion: Religious change in Greek cities under Roman rule. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1 -20. [ Links ]

Hengel, M. 1990. The Old Testament in the fourth gospel, Horizons of Biblical Theology 12:19-41. [ Links ]

Jones, L.P. 1997. The symbol of water in the gospel of John. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Keener, C.S. 2003. The gospel of John, vol. 1. Grand Rapids: Baker. [ Links ]

Koester, C.R. 2003. Symbolism in the fourth gospel, 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Koester, C.R. 2015. Revelation. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kouremenos, A. (ed.). 2018. Insularity and identity in the Roman Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxbow. [ Links ]

Youl Lee, H.Y. 2014. A dynamic reading of the Holy Spirit in Revelation: A theological reflection on the functional role of the Holy Spirit in the narrative. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Mealy, J.W. 1992. After the thousand years: Resurrection and judgment in Revelation. Sheffield: JSOT Press. [ Links ]

Menken, M.J.J. 1996. Old Testament quotations in the fourth gospel. Kampen: Kok Pharos. [ Links ]

Merkelbach, R. and Stauber, J. 1998. Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten Stuttgart/Leipzig: K.G. Saur. [ Links ]

Mounce, R.H. 1977. The book of Revelation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Moyise, S. 1995. The Old Testament in the book of Revelation. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Ng, W-Y. 2001. Water symbolism in John: An eschatological interpretation. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Nida, E.A. and Louw, J.P. 1988. Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament. New York: American Bible Society. [ Links ]

Orepeza, B.J. 2019. Corinthian audience competency: How much did the Corinthians know about Scripture? Paper presented at the Bildung und Religion Symposium, Göttingen, 30 May to 1 June, pp. 1-10. Online: https://www.academia.edu/39594258/Corinthian_Audience_Competency_How_much_did_the_Corinthians_Know_about_Scripture (viewed 30 September 2019). [ Links ]

Page, N. 2014. Revelation Road. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [ Links ]

Parke, H.W. 1985. The oracles of Apollo in Asia Minor. London: Croom Helm. [ Links ]

Peterson, E. 1988. Reversed thunder. San Francisco: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Pleket, H.W. and Stroud, R.S. 1989. Patmos. Epigram for Vera, hydrophoros of Artemis Patmos, 3rd/4th cent. A.D., Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 39(855). Leiden: Brill, pp. 261-262. [ Links ]

Rea, J. 1990. The Holy Spirit in the Bible. Lake Mary, FL: Creation House. [ Links ]

Schuddeboom, F.L. 2009. Greek religious terminology - Telete & Orgia: A revised and expanded English edition of the studies by Zijderveld and Van der Burg. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Smalley, S.S. 1989. 1, 2, 3 John. Dallas: Word. [ Links ]

Smalley, S.S. 1994. Thunder and love: John's Revelation and John's community. Milton Keynes, UK: Word. [ Links ]

Smalley, S.S. 1998. John evangelist and interpreter, 2nd ed. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity. [ Links ]

Smalley, S.S. 2005. The Revelation to John. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity. [ Links ]

Smith, G. 2009. Isaiah 40-66. Nashville: Broadman & Holman. [ Links ]

Stanley, C.D. 2008. Paul's 'use' of Scripture: Why the audience matters. In S.E. Porter and C.D. Stanley (eds), As it is written: Studying Paul's use of Scripture. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, pp. 125-156. [ Links ]

Swete, H.B. 1911. The Apocalypse of St. John. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Thomas, J.C. and Macchia, F.D. 2016. Revelation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Tibor, G. 1989. Patmiaka: Two studies on ancient Patmos. Budapest: Eötvös Collegium. [ Links ]

Tõniste, K. 2016. The ending of the canon: A canonical and intertextual reading of Revelation 21-22. London: Bloomsbury T& T Clark. [ Links ]

Weinrich, W.C. (ed.). 2005. Revelation. In T.C. Oden (ed.), Ancient Christian commentary on Scripture, vol. 12. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity. [ Links ]

Wemyss, T. 1840. A key to the symbolical language of Scripture. Edinburgh: Thomas Clark. [ Links ]

Westcott, B.F. 1881. The gospel according to St. John. London: John Murray. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. 2005. The early Christians in Ephesus and the date of Revelation, again, Neotestamentica 39(1):163-193. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. 2007a. The victor sayings in the book of Revelation. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. 2007b. Revelation: Illustrated Bible backgrounds commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. 2008. The rise of Christian oracles in the shadow of the Apollo cults, Ekklesiastikos Pharos 90:162-175. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. 2019. Geography of the Island of Patmos. In B. Beitzel (ed.), Lexham Geographic Commentary: Acts through Revelation. Bellingham, WA: Lexham, pp.619-628. [ Links ]

1 I wish to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments helped to improve the article, as well as my doctoral student Jeremy Painter for his useful insights. Any errors that remain are my own.

2 Despite the omission of "sea" in her statistical discussion, Crutcher does mention two events in the Fourth Gospel that occurred on the Sea of Galilee/Tiberias (John 6:16-21; 21:1-19). Of course, "sea" is a misnomer since it is really a freshwater lake fed by the Jordan River.

3 Nida and Louw list both κολυμβήθρα and πηγή under "Constructions for Holding Water" in domain 7.57-58.

4 There are four uses in 1 John: 5:6 (3x) and 5:8. After reviewing various interpretative options for these challenging verses, Smalley (1989:278) writes: "John is speaking here of the terminal points in the earthly ministry of Jesus: his baptism at the beginning, and his crucifixion at the end." His view that the reference to water here is historical (cf. John 1:26-34) rather than sacramental, is persuasive.

5 Revelation is presented first in the discussion and in the charts based on the presupposition that the Apocalypse should be dated early to the late 60s while the Fourth Gospel was written after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE; see Smalley (1994:40-50) and Wilson (2005).

6 The issues concerning the connectivity and insularity of Mediterranean islands through various periods has been a topic of much recent scholarly discussion; see, for example, the ten articles in Anna Kouremenos (2018).

7 The variant reading πόντος ("open sea") is found in Rev. 18:17.

8 The genitival form ζωής is used in other constructions in Revelation: tree of life (2:7; 22:2, 14, 19), wreath of life (2:10), book of life (3:5; 13:8; 17:8; 20:12, 15; 21:27), and breath/soul of life (11:11; 16:3). Hence this translation is preferred over the adjectival one "living water" given, for example, in the NIV and ESV translations. Interestingly, both translate to "water of life" in 21:6 and 22:1, 17, so the translations are not consistent.

9 The phrase "springs of water" also represents a natural phenomenon in Rev. 8:10; 14:7; and 16:4.

10 Paul interprets this rock as Jesus in 1 Cor. 10:4.

11 One of the new "waters" of idolatry from which Judah was drinking was the Euphrates River (Jer. 2:18). Craigie, Kelley, and Drinkard (1998:33) write: "Israel had exchanged the 'fountain of living water' for 'leaky cisterns'; now, with cisterns empty, it would seek water from Egypt or Assyria, but yet would fail to return to the source of 'living waters'." For John the great river Euphrates was the place from which the demonic enemies of God will gather and advance for the last battle (Rev. 9:14; 16:12).

12 Goppelt, ύδωρ, 325.

13 All English translations are from the NIV except those in Revelation which are my own. The Greek text of this and the other verses discussed are shown in chart 2.

14 This final saying is introduced by the epithet, "I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End." In 1:8 "Alpha and Omega" is also used as an epithet for the Lord God Almighty. Thus Fekkes (1994:262), comments, "The promise follows the same structural pattern as the eschatological rewards of the letters (Rev. 2-3), except that here God is the speaker." Whereas in 1:8 the Alpha and the Omega is the Lord God, it is better here to view the Alpha and the Omega as the Lamb-Jesus; a view validated by the title's use one more time in 22:13 (with the Beginning and the End).

15 Beasley-Murray (1978:313), likewise states: "The promises to the conquerors, declared in the seven letters in chapters 2-3, therefore find their summary expression at this point."

16 Smalley (2005:201) writes similarly: "The 'springs of living water' in verse 17 become in the final vision of Rev. 22.1, 'a river of the water of life', flowing through the heavenly city from the joint throne of God and the Lamb."

17 Wemyss (1840:362) uses these and other Old Testament texts to inform his statement that "rivers and streams are used as symbols of the Holy Spirit".

18 Most Eastern Fathers interpret v. 38 as the believer because they do not believe in a double procession of the Spirit but only from the Father. Jerome, referring to this verse in Homilies on the Psalms 1, writes, "We believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, that is true, and that they are a Trinity; nevertheless, the kingship is one"; see Weinrich (2005:387).

19 The language of Goppelt (1983:325), who notes further that the metaphor explained by the appended ζωής "does not occur in the OT verses".

20 Smith (2009:494) observes that "the sustenance and covenant mentioned in 55:1-5 are not offered to just people from Zion; they are available to everyone who comes to partake, including the nations (55:5)". This invitation is similarly given in Odes of Solomon 30:1-2: "Fill for yourselves water from the living spring of the Lord, because it has been opened for you. And come all you thirsty and take a drink, and rest beside the spring of the Lord" (Charlesworth trans.).

21 For more on the hearing sayings, see Wilson (2007a:71 -5).

22 Compare Tõniste (2016:189).

23 See, for example, Brown (1966: CXVI-CXXI).

24 Smalley (1998:265-70).

25 Nevertheless, Koester (2003:176) observes, "The water motif in the Fourth Gospel is less consistent than that of light and darkness."

26 The composition of the Fourth Gospel is an elusive and debated quest in Johannine scholarship. For a survey of the issue see, for example, Keener (2003:81-139).

27 Thus Smalley (1998:201) writes about living water: "The Apocalypse and Gospel of John are closely associated in their common use of this imagery."

28 Barrett (1978:195) likewise notes that living water in the Old Testament sometimes stands for the Holy Spirit and is "a metaphor for divine activity in quickening men to life".

29 Tyconius in his Commentary on the Apocalypse already linked this promise in John 4:14 (cf. 6:35) to "drink from a cup so excellent" with Rev. 7:16-17; see Weinrich (2005:115).

30 Burge (1987:96-9), however, holds that the water signifies only the Spirit.

31 See Smalley (2005:541).

32 Eisenstein (1906:476) states, "At the morning service on each of the seven days of the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) a libation of water was made together with the pouring out of wine (Suk. iv. 1; Yoma 26b), the water being drawn from the Pool of Siloam in a golden ewer of the capacity of three logs."

33 Cf. Jerusalem Talmud, tractate Sukkãh 5.1; Ruth Rabba 4.8 (on Ruth 2.9); Midrash Rabbah 70.8 (on Gen. 29:1).

34 For more on the background of the feast and its pneumatological significance, see Gates Brown (2003:152-4).

35 Regarding John 7:39, Westcott (1881:123) makes the strange comment about the anarthrous nature of pneuma here: "When the term occurs in this form, it marks an operation, or manifestation, or gifts of the Spirit, and not the person Spirit." Although he provides a number of examples, such a fine distinction cannot be made because an article is lacking.

36 Brown (1966:328) observes in his note on v. 39 that water symbolising spirit, while strange to the Western mind, is well attested in Hebrew (p. 324). He then gives a number of examples to support his claim, concluding that water in v. 38 "stands both for the Spirit and for Jesus' teaching".

37 Crutcher (2015:10) responds by stating "this is an inaccurate generalization".

38 Goppelt (1983:326) characterises Jesus' gift of living water that becomes a well of water as "His Word...His Spirit... and He Himself... all in one".

39 This conclusion differs from that of Goppelt (1983:326) who likewise recognises a difference in conceptual background. For him "Rev. uses OT promises as figures for the NT gift of salvation." However, the Gospel does not have a single Old Testament text in view but "the frequently promised eschatological dispensing of water". For the Fourth Gospel he emphasises its dualistic and Gnostic concepts.

40 For more on the island and its history, see Wilson (2019).

41 The inscription (Syll. 11.52), dated to the 2-3 century CE, is now displayed in the monastery's museum. For a recent reconstruction and interpretation of this lacunose text, see Tibor (1989:3-6); cf. Pleket and Stroud (1989). A photograph and translation can be found at: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/inscription-from-the-temple-of-artemis/GAF0MCAsXjXTGw.

42 Boxall reflects the discussion of Guérin (1856:17-8, 59).

43 The translation posted next to the inscription in the monastery states that Vera was the "10" hydrophoros. This has been interpreted to imply "generations": Vera was the tenth in a line of priestesses who had served the cult. However, the corrected translation mentioned in note 68 no longer gives that reading.

44 The term υδροφόρος is found three times in the Septuagint to describe foreigners in the camp of Israel whose duties were those of water carriers (Deut. 29:10; Josh. 9:21, 27).

45 Bremmer (2008:10) suggests that such adolescent females would have served as hydrophoroi, whether at Didyma, Ephesus, or Patmos.

46 Knidos: 3-2 century BCE (http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=400304&partId=1); Tralles: 4 century BCE (https://journals.openedition.org/acost/620); and Rhodes: late 5 BCE (http://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/442482). The Sadberk Hanim Museum in Istanbul has a similar figurine from the same period but does not give its provenance (http://www.sadberkhanimmuzesi.org.tr/en/collection/figurine).

47 This identification is apparently based on the hairstyle of the young woman and the shape of the jar; however, no provenance is given (https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/290846).

48 For more about the office of prophet and prophecy at Didyma, see Wilson (2008).

49 Heller (2017:18) notes further that commemorative inscriptions "are private texts, inscribed by the officeholder after completing his year in office, to record his actions on behalf of the community". The most frequent laudatory epithet used for the hydrophoroi is eusebeis (pious), used on 68% of all inscriptions.

50 Such libation offerings using water resembled those practiced by Jews for the Feast of Tabernacles; see note 50.

51 This is evident in the frequent use of explanatory asides in water contexts in John's gospel: water jars (2:6), Jacob's well (4:5-6), Bethesda pool (5:2), Galilee/Tiberias lake (6:1), and Siloam pool (9:7).

52 See also Carter (2008) who also situates his study in and around Ephesus; see particularly chapter 3, "Expressions of Roman power in Ephesus".

53 In Revelation Old Testament historical figures such as Balaam and Jezebel (Rev. 2:14, 20) are unexplained, while in the Fourth Gospel titles such as Rabbi and Messiah (John 1:38, 41) are translated. In the gospel Cephas is also translated (John 1:42) while in Revelation the names Abaddon/Apollyon are given both in Hebrew and Greek (Rev. 9:11). This and the isopsephism 666, commonly calculated as NERON KAISAR in Hebrew, suggest there were still Hebrew speakers in Revelation's audience. However, when the Fourth Gospel was written, their number was probably reduced.

54 For Revelation see Moyise (1995) and Beale (1998); cf. Beale (1999:76-99). For examples in the Gospel of John see Barrett (1947), Hengel (1990), and Menken (1996).

55 Stanley (2008:143) goes on to comment that even literate Gentiles who might have attended the synagogue and studied scriptural texts for themselves "would have been quite rare".

56 Abasciano (2007:167) pushes back on Stanley's negative view of scriptural competency in the early Pauline churches but allows specifically that it was Gentile God-fearers who "may have been very familiar with Scripture through contact with the synagogue". While Gentiles without synagogue experience might have become effective interpreters of scripture, their number in the Asian churches must have been few.

57 This assumes the view that the ίδιώται in early Christian assemblies were actually untutored inquirers "who have shown some interest in the Christian faith but who have not yet taken the step of expressing a clear faith commitment and joining the church through baptism"; see Ciampa and Rosner (2010:704).

58 Orepeza (2019:5) writes: "We can adduce from texts like 1 Cor 8:7 and 12:2 that the Corinthians are Gentiles and former idolaters. They did not grow up with Jewish Scripture."