Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.118 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/118-1-1528

ARTICLES

The restoration of the "dry bones" in Ezekiel 37:1-14: an exegetical and theological analysis

Joel Kamsen Tihitshak BiwulI; ECWA Theological Seminary (JETS)II

IResearch Fellow, Old and New , Testament Stellenbosch University

IIJos, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

The visionary presentation of "Dry Bones" in Ezekiel 37 presupposes the possibility of the restoration of Yahweh's covenant people to their ancestral land in ancient Palestine. What, therefore, is the underpinning theological significance? Using an exegetical and theological analysis, this article argues that the Babylonian captivity had a divine retributive and punitive purpose for a dissident covenant people, and, ultimately, achieved the recognition of the prophetic formula in Ezekiel. It concludes that only Yahweh, acting in his divine economy, and through his divine method, reserved the prerogative to reverse the unfortunate exilic condition of Israel. Bewildered and pessimistic readers should therefore acknowledge the display of this unitary divine sovereignty.

Keywords: Babylon/Babylonia; Dry Bones; Exile; Ezekiel; Israel; Restoration

Introduction

Ezekiel was from the Zadokite priestly tradition in Judah; exiled to Babylonia with King Jehoiachin and other Judahite nobles; and called to be a prophet to the Babylonian exiles. The existing literary text he left behind, includes him among the oral-literary prophets of Israel. Prophet Ezekiel, contra some Israelite prophets, used mostly prose narrative in his reported speech formula, with little poetry. Yet, his prophetic text encapsulates more sign-acts, oracular rebuke and elegy, symbolism and metaphors, and imageries and parables. Using oral oracles, visions, symbolic actions, and prophetic discourse (Bullock 2007:281) as communicative modes, Ezekiel's stylistic literary tradition of the imagery of "Dry Bones" is employed purposefully (Biwul 2017:1). Whether modern readers recognise this or not, Ezekiel 37's vision of "Dry Bones" attracts a wide readership. Greenberg is not mistaken when he says, "This passage, probably the best known of Ezekiel's prophecies, deserves its fame" (1997:747). It appears to be the most famous of Ezekiel's work (Lapsley 2000:169). I also agree with Block that, "No prophecy in the entire book of Ezekiel has captured the imagination of readers down through the centuries like the account of the revivification of the dry bones in chapter 37" (1992:132).

The Assyrian captives (722 BC) and the Babylonian captives (605 BC, 597 BC and 587 BC) were not only whisked away into a foreign land, but also into a political and religious context quite remote to the Jewish culture and tradition. Exile not only meant expulsion from God's land as retribution for violating his covenant (Rom-Shiloni 2006:3), but also the demise of national Israel, the loss of everything, even her identity as a people. The glimpse of hope of recovery from such an irreparable condition bewildered Ezekiel when he came face to face with the vision of the "Dry Bones". Even Yahweh's messenger himself wondered, can dry bones really live? Yet, in his use of the messenger and reported speech formulas, Ezekiel employed language that evokes ancient prophetic experiences that characterise him as possessing authoritative credentials that can be trusted (Allen 1990:184).

The visionary imagery of the "Dry Bones", described as a dramatic autobiographical narrative, with the prophet's actions playing a more significant role in the vision than in any previous visions (Block 1992:132), was necessitated by the lamentation of the disenfranchised, hopeless, traumatised and shattered Babylonian exiles regarding their condition. Clearly, the vision reveals the pervasiveness of death against the historical backdrop of the crisis of survival (Powery 2012:20). Represented by the imagery of death, exile was Yahweh's punishment for Israel's spiritual infidelity (Block 1992:133). Death means cessation and physical loss; exilic Israel had lost all her institutions. Any hope of reparation and restoration, either in part or in full, was merely a mirage. Yahweh put on such an unbelievably dramatic display purposefully "to combat the despair which had settled upon the [agonising] exiles" (Cooke 1970:397). But what is the theological significance of this portent, the visionary imagery of "Dry Bones", for exilic Israel? I will employ an exegetical and theological measuring grid in response as I proceed with the analysis.

The Uniqueness of the Book of Ezekiel

The book of Ezekiel is situated among the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew canon, one of the five books of the Major Prophets out of seventeen Hebrew Writing Prophets in the Christian canon. Of these, the book of Ezekiel seems to be the most exciting. Apart from its four major visionary experiences (Ezek. 1; 8; 37; 40) and dramatic aspects, it is also unique in other respects.

Firstly, while other Israelite prophets were called to be prophets in Palestine, either in the North or the South, according to internal evidence Ezekiel, as one of the Babylonian exiles, was called in a foreign land, in Babylonia (Ezek. 1:1; 2:2-7; 3:10-11). When Nebuchadnezzar raided Jerusalem in 605 BC, he took materials and people (see Dan 1:1-4, 6-7; 3:12-14). He returned in 597 BC and carried away more people, including Ezekiel. Cooke captures the impact of Ezekiel's visionary experience thus: "A VISION of God in His glory and holiness, enthroned yet in motion, approaching to reveal Himself outside the land of Israel: this conveyed to Ezekiel in Babylonia a call to prophecy. It determined the substance of his message. He could never forget what he had seen and heard" (1970: xvii). This prophetic call outside Yahweh's land of abode, sets aside his supposed immobility, and allows for his mobility as Sovereign Yahweh. Shortly after Ezekiel's call to the prophetic function, Jerusalem was finally destroyed by Babylon in 587 BC as both Jeremiah and Ezekiel had prophesied would inevitably occur (Jer. 1:16; 2:19; 13:19; 24:1; Ezek. 4:16; 17:12).

Secondly, Ezekiel's call to be a prophet came at a crucial point in the history of covenantal Israel. It was a turbulent and threatening time as the city of Jerusalem, the cultural, religious, and economic centre of Jewish life (Powery 2012:20), was at risk of demise at the hands of the Babylonians. The final dissolution and therefore the disappearance of the city, temple, priesthood, and monarchy (Ezek. 33:21, 27-29) was an event God had already purposed on the grounds of Israel's persistent covenantal infidelity. Yet, the prophet could not convince the rebellious, obstinate, unbelieving and resistant Babylonian exiles to admit their sin as the cause of this calamity and turn to Yahweh in repentance for mercy (Ezek. 2:2-5; 3:7, 11). The sequential crises of events that culminated in the total collapse of the Jewish institutions and the disappearance of their national and religious identity not only, as Blenkinsopp (1990:12) points out, ". . . threaten to undermine the religious assumptions on which their lives are based. . . . [But] the very possibility of worship was called into question" as well. This eclipse of national identity and institutions presupposes the demise and disappearance from history of Israel as a nation in a covenant relationship with Yahweh.

Thirdly, the effects of false prophecy in Judah concerning the duration of the Babylonian captivity (Ezek. 13:1-16; 22:28; see Jer. 5:31; 14:13-15), and the disbelief of the exiles in Ezekiel's prophecy about the impending demise of Jerusalem, made his prophetic words ineffectual to the exiles (Ezek. 12:2-3). This disbelief in an indubitable event was anchored in their traditional belief in the inviolability of Jerusalem as Yahweh's residential city vis-â-vis the Davidic covenant (2 Sam. 7:1-29; 1 Chron. 22:116; 28:6; 2 Chron. 7:17-18). The psychology of Ezekiel's primary audience compelled him to become the most dominant and famous choreographic dramatist of the Hebrew prophets. This feature led Ogunkunle to perceive the book as being ". . . full of the personal experiences of the prophet" (2007:160).

Fourthly, the switch in Ezekiel's prophetic function from a judging orator to a consoling rhetorician, is significant. The cause of the Babylonian captivity was indisputably Israel's persistent sin in disrespecting Yahweh's holy name and honour (Ezek. 20:9, 14, 22, 44; 36:20-23; 39:7, 25; 43:7-8). But exilic experience had a retributive and punitive outcome. On hearing the news of the final demise of Jerusalem (33:21), the disbelieving and resistant exiles became socio-psychologically disenfranchised and theologically disoriented and shattered. Blenkinsopp describes their psychology thus, "These communities were trying to pick up the pieces of their lives after passing through a terrible trauma. Their land had been devastated, the temple destroyed, many of their friends and relatives were dead, missing, or left behind, and they had to begin a new life from scratch" (1990:17). Consequently, the context of Ezekiel's ministry warranted that ". . . he had to be a creative theologian, doing far more than reinterpreting the prophetic tradition for his own time" (Gowan 1998:121).

Lastly, the pervasively dominant recognition formula in Ezekiel ("you will know/they will know") sets it apart. Both in judgement and in restoration, Yahweh shows himself as one who unitarily controls cosmic events and human history. He judges and punishes both the wicked and the righteous to instil awe and enthrone himself in divine sovereignty. According to Powery (2012:107), the excavation and resurrection of a deceased Israel from her grave, serving as the ultimate end of God's story for his people, irresistibly moves its recipients to a state of awful and reverential acknowledgement of his sovereignty.

The preceding uniqueness lays the foundation for my analysis of the prophet's visionary imagery of "Dry Bones".

The Restorative Imagery of "Dry Bones" in Ezekiel 37

Lapsley construes the entire book of Ezekiel (and I add, particularly Ezekiel 37) as "an earnest attempt to persuade a despairing audience to envision themselves as part of a future blessed by God, and to that end, to embrace their role in the restoration of national life" (2000:2). The thread that runs through Ezekiel 34 to 48, described by Block (1998:268) as the gospel of hope according to Ezekiel, is its salvific principle. Yahweh would actualise this hope for Abraham's descendants because of his covenantal fidelity and mercy. Ezekiel 37, therefore, falls within the restoration section of this prophetic book. It is divided in two clear sections: the prophet's visionary experience of the valley of "Dry Bones", visualising the dead state of Israel (vv. 1-14); and the graphic eventual realisation of postexilic reunification of the dispersed tribes of Judah and Israel (vv. 1528). Verses 1-14, which is my concern, is also divided into two literary sub-units: the introductory epilogue, presented in a prophetic reported speech formula (vv. 1-4); and the divine speech, couched in the messenger formula (vv. 5-14).

Karin Schöpflin (2005:101) admits to the varied presence of imageries in the Writing Prophets. The language of imagery was used by the Hebrew prophets in particular to paint a vivid mental picture of the essence of the prophetic message being communicated. In this way, it functions as a catchword or like a luring device that traps a fish in the fishing net (Biwul 2017:2). Israelite prophets used imagery to transmit the divine message through the prophetic word more vividly and concretely. Nissinen (2003:1-2) notes that this process of transmission consists of four components: the divine sender of the message; the message itself; the human transmitter of the message; and the recipient of the message.

Israelite prophets also engaged in the stylistic and artistic use of imagery to achieve their emotive agendas. This became unavoidable because prosaic expression was inadequate; hence, ". . . poetry as an emotional, deep expression of faith and worship became a necessity" (Osborne 2006:231). To be sure, the engagement of prophetic imagery is largely situated in the relationship of Yahweh with his covenant people. The core of imaging linguistic expression in Ezekiel captures this interwoven thread, culminating in the striking vision of "Dry Bones".

The Prophetic Description of the Condition of the Bones

The visionary dramatic display recounted by Ezekiel took place in a valley, הַבִּקְעָה בְתוֹךְ , in the middle/midst of it. It was a lifeless environment, likely an ancient battlefield filled with bones of the slain that had been lying there for years. Importantly, the prepositional function of situating Ezekiel in the centre, was so he could have a full view of all the bones and their state of absolute dryness. Yahweh instructing Ezekiel to pass over/walk upon the bones, clearly supports this (37:2). Ezekiel describes the state of the bones that he saw in the valley as very dry (37:2). The descriptive Hebrew particle adverb used here is dm, translated as very (ASV, ESV, GNV, KJV, NAS, NET, NIV, NKJ, NRS, RSV, TNK, YLT), completely (nJB, NLT), and so (CJB). Adverbial words like this usually stand with nouns, describing the status or condition of the object of association. In this case, it is the bones in the valley. The Hebrew  translated as bone, is used elsewhere in the Old Testament, in its poetic form (Gen 2:23; Prov 15:30), and in its literal form (Ezek. 39:15). The plural form niacs; also has a dual function. It functions in both a literal sense (Exod. 13:19; Jos. 24:32; 2 Sam. 21:12-14; 2 Kgs. 23:14; 2 Kgs. 23:18; 2 Kgs. 23:20) and in a poetic sense (Ps. 51:10; Prov. 14:30; Jer. 8:1; Amos 2:1).

translated as bone, is used elsewhere in the Old Testament, in its poetic form (Gen 2:23; Prov 15:30), and in its literal form (Ezek. 39:15). The plural form niacs; also has a dual function. It functions in both a literal sense (Exod. 13:19; Jos. 24:32; 2 Sam. 21:12-14; 2 Kgs. 23:14; 2 Kgs. 23:18; 2 Kgs. 23:20) and in a poetic sense (Ps. 51:10; Prov. 14:30; Jer. 8:1; Amos 2:1).

However, of all the occurrences of the word in both its singular and plural forms, only Ezekiel's use of  for bone in chapter 37 is specific to the humanly irreparable and irrecoverable condition of Israel in exile. This prepares the ground for the Hebrew adjective

for bone in chapter 37 is specific to the humanly irreparable and irrecoverable condition of Israel in exile. This prepares the ground for the Hebrew adjective  for dry, which suggests not only the deplorable state of the bones, but also their condition of total deadness. The condition of Yahweh's covenant people captured in the imagery of bones is described as very dry, so dry, and completely dry. The bones had been dried out exceedingly, greatly, lying waste in their lifeless state in the valley, and therefore not good for anything. According to Greenberg, what Ezekiel saw was not skeletons; rather, it was a sea of disjointed bones, each separated from its mates, clearly revealing the extremity of their deterioration (1997:742).

for dry, which suggests not only the deplorable state of the bones, but also their condition of total deadness. The condition of Yahweh's covenant people captured in the imagery of bones is described as very dry, so dry, and completely dry. The bones had been dried out exceedingly, greatly, lying waste in their lifeless state in the valley, and therefore not good for anything. According to Greenberg, what Ezekiel saw was not skeletons; rather, it was a sea of disjointed bones, each separated from its mates, clearly revealing the extremity of their deterioration (1997:742).

The emotive picture that the reader visualises of the intensity/degree of the dryness of the bones, is to the effect that they would not even attract a dog sniffing them. This descriptive extremity of Israel's exilic experience ". . . sums up well the situation of the exiles . . . [as] the personification of the bones reflects the fact that they represent the exiles" (Joyce 2009:208), whose political and religious conditions were indeed very dry, indicating both a hopeless and an irreparable condition. This metaphor of unburied dry bones is well captured by the exiles' intense expression: "Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off" (37:11). Allen points out that the metaphor of death, as expressed in this lament, describes "an abysmally low level of human existence that, crushed by crisis, lacked any of the quality that life ordinarily had" (1990:186). The word ΊΤ3  for "cut off", is used here to indicate the separation, detachment, alienation, expulsion, and exclusion of the Jews from their land of ancestry. As Tuell confirms, ". . . texts from around the time of the exile use gazar for separation in a more abstract sense" (2009:262). It is this hopeless condition following the demise of Jerusalem that compelled Ezekiel to use this imagery as a means of comfort for the exiles, offering hope of their restoration and transformation (VanGemeren 1990:327).

for "cut off", is used here to indicate the separation, detachment, alienation, expulsion, and exclusion of the Jews from their land of ancestry. As Tuell confirms, ". . . texts from around the time of the exile use gazar for separation in a more abstract sense" (2009:262). It is this hopeless condition following the demise of Jerusalem that compelled Ezekiel to use this imagery as a means of comfort for the exiles, offering hope of their restoration and transformation (VanGemeren 1990:327).

The Theological Import of the Status Description of the Bones

The Hebrew prophets were sages, poets, and theologians. As Gowan (1998:1) notes, their books are "works of theology" because, in them, the prophets claim to explain Yahweh's role and actions in historical events. This theology plays out in Ezekiel's visionary imagery of "Dry Bones".

At least five theological imports are apparent in Ezekiel 37:1-14. Ezekiel's glaring use of Yahweh's hand and the Spirit indicates his theological representation of the divine presence. Readers of Ezekiel encounter the crucial literary phrasal expressions "The hand of the LORD was upon me" and "by the Spirit of the LORD" several times. The text indicates their dominant occurrences: the first occurs in 1:3; 3:22; 8:1, 3; 37:1; and 40:1, and the second occurs in 2:2; 3:12, 14, 24; 8:3; 11:1, 2, 5, 24; 36:27; 37:1, 14; 39:29; and 43:5. Pneumatology in Ezekiel functions as a transporting agency, suggestively replicating the hovering role of  (Spirit of God) at creation (Gen. 1:2). In this particular visionary experience, ". . . the prophet finds himself carried away and deposited in a valley" (Block 1998:373). The theology of Yahweh's permeating presence in Ezekiel thus displaces the hitherto held view of his immobility as a localised deity.

(Spirit of God) at creation (Gen. 1:2). In this particular visionary experience, ". . . the prophet finds himself carried away and deposited in a valley" (Block 1998:373). The theology of Yahweh's permeating presence in Ezekiel thus displaces the hitherto held view of his immobility as a localised deity.

Secondly, a resurrection theology emerges in two phases (vv. 7-8). Bullock notes, "The valley of dry bones and their resuscitation primarily constitute a message of return from captivity and restoration to the land" (1998:301). The rattling sound of the bones, their coming together, their having tendons and clothing with flesh, their being covered with skin in response to the prophetic declaration, is indicative of resurrection theology. Israel's exilic condition was hopeless and practically irreparable. The people had lost the priesthood and its rituals; the monarchy and its respect; the temple and its glory; Zion, the city of David/Yahweh and its integrity; Yahweh's presence and glory; their ancestral land; and their pride as a people. Israel, regrettably, lost such national repertoires when her ancestral land was disposed and, subsequently, was forcefully deposited in a foreign land. And, worst of all, the people now ". . . lived in an alien culture that denied the truth of their ancestral faith" (Gowan 1998:123). As Gowan rightly states, there was practically no ". . . likelihood that they could achieve and maintain an identity that could preserve the uniqueness of the Yahwistic faith under these conditions" (1998:123). The claim of the exiles: "Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off" (Ezek. 37:11b NIV) clearly expresses this frustratingly hopeless condition. But the imagery of the "Dry Bones" reversed this perception. But although the bones became skeletons, tendons and flesh were put on the exceedingly dry bones, and skin covered them, yet they were still lifeless corpses (vv. 7-8).

In the second phase of the resurrection, the imagery also conveys an embedded resuscitative theological element (vv. 9-10) which flows from the theological stream of resurrection. Ezekiel's obedience to Yahweh's imperative (in the Niphal root) to prophesy  to the dry bones (Ezek. 37:4, 7), is immediately followed with the divine advance explanation of what the effects of the action would be (Ezek. 37:5-6). It would result in the resuscitation of the bodies now lying lifeless and motionless in bodily form. The prophetic declaration of life for the dry bones against natural laws, rational human imagination, and common sense would resurrect and resuscitate the bodily forms into living humans described as a "vast army" (Ezek. 37:10). Blenkinsopp (1990:173) perceives this life-giving event as a re-enactment of the primal act of creation, pari passu in the events of Gen 2:7. Block explains that the corpses were revived by the specific direct act of Yahweh; for it is he who infused them with breath. Consequently, "The two-phase process of resuscitation also serves a theologico-anthropological function, emulating the paradigm of Yahweh's creation of [Adam]" (Block 1998:379). Cooke affirms that this re-animation of dry bones into living humans can only be "a mighty act of Jahveh, who alone can do what to human eyes looks impossible" when he brings to life truly dead corpses (1970:397).

to the dry bones (Ezek. 37:4, 7), is immediately followed with the divine advance explanation of what the effects of the action would be (Ezek. 37:5-6). It would result in the resuscitation of the bodies now lying lifeless and motionless in bodily form. The prophetic declaration of life for the dry bones against natural laws, rational human imagination, and common sense would resurrect and resuscitate the bodily forms into living humans described as a "vast army" (Ezek. 37:10). Blenkinsopp (1990:173) perceives this life-giving event as a re-enactment of the primal act of creation, pari passu in the events of Gen 2:7. Block explains that the corpses were revived by the specific direct act of Yahweh; for it is he who infused them with breath. Consequently, "The two-phase process of resuscitation also serves a theologico-anthropological function, emulating the paradigm of Yahweh's creation of [Adam]" (Block 1998:379). Cooke affirms that this re-animation of dry bones into living humans can only be "a mighty act of Jahveh, who alone can do what to human eyes looks impossible" when he brings to life truly dead corpses (1970:397).

The resurrection and resuscitation of these exceedingly dried bones moves the prophetic narrative from the state of disorientation to reorientation to demonstrate that such power would be proof indeed of Yahweh's being (Allen 1990:185). Readers are therefore never left in doubt to the effect that only Yahweh can do what humans are incapable of. For in Ezekiel's eschatological vision, it is the singular creative activity of God that fashions a new people; this action is the product of a unilateral divine action (Lapsley 2000:39, 159).

Thirdly, a restorative theological focus is clear from the "Dry Bones" imagery (vv. 11-12). The prophetic narrative reveals that the promised actualisation of this divine futuristic action of restoration, captured in the imagery of the grave, would begin with Yahweh's excavation of the graves and the exhumation of the dead bones from them (Ezek. 37:12). The ancient tradition of reopening the varied family rock-cut tombs every time a family member died, so the person could be gathered to the ancestors (Block 1998:381), was reversed in Ezekiel. Yahweh was instead to revive the bones into corpses, give breath and life to them, then bring them out of the tombs. Block grounds the necessity for a restorative theology on Israel's losses when he says, Israel had ". . . lost all hope in their future and all hope in God. The nation obviously needs deliverance not only from their exile in Babylon but also from their own despondency" (1998:372). This physical national resurrection would then culminate in the reunification of the Jewish race, captured by the imagery of the prophet writing on two wooden sticks and joining them together (Ezek. 37:15-22). Block (1998:376) concedes a dual element in this restoration - a physical restoration of the Israelite state and a spiritual revival of a restored relationship of Israel with Yahweh.

Fourthly, a recognition theological import is also glaring in this text (vv. 5-6, 13-14). The recognition/acknowledgement formula, "you will know/they will know" phraseology, acts as a pervasive theme song in Ezekiel. The basic theological motivation for this revival, depicted by the imagery of "Dry Bones", which later culminates in Yahweh's eschatological restoration, was to compel Israel's awareness of the being and power of Yahweh: "Then you will know that I am the LORD" (Ezek. 37:6b, 13, 14b). It is supposed that eschatology presents hope, and in the case of biblical Israel, hope remained the constant aspect in every difficult situation Israel and the Jews faced (Coetzee 2016:1). All the occurrences of recognition formula or motif in Ezekiel have dual targets: either it is directed at the gentile nations when God takes glory over them in judgement of their oppressive relationship to Israel, or specifically directed at Israel when he divinely saves them in view of her covenant relationship with him. The undergirding theology of this motif in the context of Ezekiel is significant,

In Ezekiel's text, the function of recognition formula serves to achieve an awesome recognition and admission of the greatness, power, and supreme authority of Yahweh on the part of the targeted recipients of the prophetic message. Also, it functions to achieve the purpose of clarification in the perception of the unique personhood and acts of the divine as the latter is seen displayed in the cosmic order or historic events. In this regard, recognition formula functions as an enhancer to achieve a deepened understanding of Yahweh in all the embodiment of his glory, dignity, and majesty (Biwul 2013:226).

The grounds for the prophet's engaging this formula specific to Israel, then, is unambiguous. Ezekiel's frequent use of this prophetic ". . . recognition motif points to Yahweh's faithful commitment to his covenant with the people and to reveal as well his ownership of the people. . . . This therefore clearly articulates Ezekiel's use of the shepherd metaphor within a covenantal context with a decidedly fixed eschatological motif (Biwul 2013:225-226). Israel's rejection of Yahweh for other gods would be reversed when they identified his acts in history. The transformed members of the new community would be filled with the knowledge of Yahweh and therefore unable to repeat their past mistakes (Lapsley 2000:170).

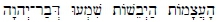

Fifthly, the display of divine sovereignty is obvious in this passage. The point is heightened by the prophetic imperative declaration,  "Dry bones, hear the word of the Lord!" (v. 4). According to Odell, "In the poetic literature, the metaphor of bones represents the totality of the human person" (2005:453). This, in turn, is used as a representation of the Jews as a people in a covenant relationship with Yahweh. The coming back to the life of these dry bones, a representation of the eschatological restoration as well as the reunification of Yahweh's covenant people, is a clear demonstration of Yahweh's sovereignty and the display of his absolute divine power of control over cosmic order and history. It reveals the essence of Yahweh as the "I am that I am" (Exod. 3:14) and his divine might when he proclaimed, "Is anything too hard for the LORD?" (Gen 18:14 NIV). It not only brings Yahweh into clear perspective as the one who directs history and historical events in human society, but also testifies to these events possessing theological imports for the careful participant or observer. Only Israel's Yahweh is capable of doing what the gods of other nations and what humans are incapable of doing. Therefore, such acts would serve as an indictment to Israel for disserting the true source of life and power for weak ones.

"Dry bones, hear the word of the Lord!" (v. 4). According to Odell, "In the poetic literature, the metaphor of bones represents the totality of the human person" (2005:453). This, in turn, is used as a representation of the Jews as a people in a covenant relationship with Yahweh. The coming back to the life of these dry bones, a representation of the eschatological restoration as well as the reunification of Yahweh's covenant people, is a clear demonstration of Yahweh's sovereignty and the display of his absolute divine power of control over cosmic order and history. It reveals the essence of Yahweh as the "I am that I am" (Exod. 3:14) and his divine might when he proclaimed, "Is anything too hard for the LORD?" (Gen 18:14 NIV). It not only brings Yahweh into clear perspective as the one who directs history and historical events in human society, but also testifies to these events possessing theological imports for the careful participant or observer. Only Israel's Yahweh is capable of doing what the gods of other nations and what humans are incapable of doing. Therefore, such acts would serve as an indictment to Israel for disserting the true source of life and power for weak ones.

This theological understanding is critically tied to Yahweh's question to Ezekiel "Son of man, can these bones live?" (Ezek. 37:3). Quite obviously, Yahweh's question to Prophet Ezekiel as to whether the bones that were exceedingly dry in their extreme state of dryness could live, is quite enigmatic. The one to whom this question is posed, is a "son of man", "mortal one", a weak and frail created being who is limited in knowledge and power. This enigma is heightened in that, "The image concretises the hopelessness [of Israel] expressed in v. 11; no life force remains in them at all. . . . the picture is one of death in all its horror, intensity, and finality" (Block 1998:374). Ezekiel knew from his priestly background that corpses do not live, even less dry bones. The bewildered prophet pondered the elusive possibility of a restored life to such bones, and responded appropriately to the Yahwistic enigmatic question; "O Sovereign LORD, you alone know" (37:3b NIV). According to Odell, Ezekiel's reply to Yahweh's question is an acknowledgement of his own failure (2005:454), and according to Greenberg, his evasion was to avoid encroaching on God's freedom (1997:743). It seems appropriate to reason that such a thoughtful response is an expression of the prophet's inadequacy and incapability of imagining that dry bones can become humans. It was a non-committal answer that reflected the exiles' crisis of faith (Welch 2016:79). In this way, the prophet acknowledged his lack of omniscience (Alexander 1986:924) as Yahweh possesses knowledge that the prophet himself does not have (Lapsley 2000:170). But Allen thinks Ezekiel declined any answer to the ridiculous divine question out of politeness (1990:184).

In terms of Ezekiel's priestly background, such a response could well have been grounded on the concept of awe, trust and dependence on Yahweh. Blenkinsopp considers this response as the prophet's expression of confidence and his knowledge ". . . that the power of God extends even into the realm of death" (1998:171). In the prophet's mind, he reasoned, "If Yahweh can bring life back to those dead, dried, scattered bones, then he can bring life back to anyone, including scattered, defeated Israel" (Hays 2010:225).

Lastly, when this vision is interpreted against the difficult context of Ezekiel's audience, the theological theme of obedience also emerges. The Judean exiles in Babylonia were rebellious, obstinate and stubborn, constantly resistant to the prophetic word (Ezek. 2:3-5; 3:7-9). But the commissioned prophet had to obey everything Yahweh would ask or direct him to do (Ezek. 2:6-8). According to Lapsley, Ezekiel's crucial role of relaying to the bones what he is told to prophesy, stands in stunning contrast to the incredulous attitude of his audience. In this, his conduct provided an example for his audience (2000:171). Acting as Yahweh's agent who was to partner with him to bring into effect this envisaged national rebirth and regathering, Ezekiel exhibited the attitude of absolute obedience in this vision (37:4, 7, 9-10). This reversal from disobedience to obedience resonated with Yahweh's purposed reversal of Israel's exilic condition to liberation.

Conclusion

Israel only discovered in exile that apart from Yahweh, she had no essence, purpose, identity and existence. Her consistent obedience and religious fidelity to her deity were what ensured her survival. The reversal and revitalisation of the exilic condition of dissident captive Judeans were solely within divine sovereignty; any human effort was futile. The controlling purpose of the visionary experience of "Dry Bones" in Ezekiel 37:1-14 was not only crucial to Israel's history, but also particularly critical to Ezekiel's eschatological theology. This vision forms the core of Ezekiel's prophecy, serving as the ligament that sustains the parts of the book.

Only Yahweh could save exiled Israel from her despondent state of existence; for she was incapable of self-deliverance. Clearly, then, it was Yahweh who directed both the events of the Assyrian and the Babylonian exiles as his punitive agents towards whoring Israel, to call her back to himself. By the same token, Yahweh himself alone could dig captives out of their grave and return them to their land of ancestry; a land hitherto dispossessed by their enemies.

The basic purpose of recognition theology replete in the book of Ezekiel would be actualised when the vision came to fruition by the hand of Yahweh. God acting to reverse the hopeless condition of the Babylonian captives and restore them was in order to sustain the integrity and the honour due to his name. When he put his plan into effect, both the Assyrian and Babylonian captives and their captors would recognise that there is no deity more powerful than Israel's Yahweh. True to Yahweh's word, the Jews became free to return to Israel, firstly under the Persian king, Ahasuerus/Xerxes, then under Zerubbabel in 538 BC, under Ezra the scribe in 458 BC, and finally, under Nehemiah in 444 BC.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, Ralph H 1986. "Ezekiel." In The Expositor's Bible Commentary Volume 6. Edited by Frank E Gaebelein. Grand Rapids, Zondervan, pp 735-996. [ Links ]

Allen, Leslie C 1990. Ezekiel 20-48: Word Biblical Commentary Volume 29. Dallas: Word Books. [ Links ]

Biwul, Joel KT 2013. A theological examination of symbolism in Ezekiel with emphasis on the shepherd metaphor. London: Langham Monographs. [ Links ]

Biwul, Joel KT 2017. "The vision of 'Dry Bones' in Ezekiel 37:1-28: Resonating Ezekiel's message as the African prophet of hope." HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 73(3), a4707. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4707. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, Joseph 1990. Ezekiel: INTERPRETATION - A Bible commentary for teaching and preaching. Kentucky: John Knox. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel I 1992. "Beyond the Grave: Ezekiel's Vision of Death and the Afterlife." Bulletin for Biblical Research 2:113-141. [ Links ]

Block, Daniel Isaac 1998. The Book of Ezekiel chapters 25-48. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Michigan: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Bullock, Clarence Hassell 2007. An introduction to the Old Testament: Prophetic books. Updated ed. Chicago: Moody. [ Links ]

Coetzee, J 2016. "Ideology as a factor for the eschatological outlook hidden in a text: A study between Ezekiel 37 and 4Q386 fragment HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 72(4), a4343. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i4.4343. [ Links ]

Cooke, GA 1970. A Critical andExegetical Commentary on the Book of Ezekiel. Reprint. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Day, John (ed.). 2010. Prophecy and prophets in ancient Israel: Proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament seminar. London: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Gowan, Donald E 1998. Theology of the Prophetic Books: The death and resurrection of Israel. Kentucky: Westminster John Knox. [ Links ]

Greenberg, Moshe 1997. Ezekiel 21-37: The Anchor Bible Volume 22A. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Joyce, Paul M 2009. Ezekiel: A commentary. Paperback ed. London: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Lapsley, Jacqueline E 2000. Can These Bones Live? The Problem of the Moral Self in the Book of Ezekiel. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Nissinen, Martti with contributions by C.L. Seow and Robert K. Ritner. 2003. Writings from the ancient world: Prophets and prophecy in ancient Near East Number 12. Peter Machinist (Ed.). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [ Links ]

Odell, Margaret Sinclair. 2005. Ezekiel. Georgia: Smyth & Helwys. [ Links ]

Ogunkunle, CO 2007. "Prophet Ezekiel on false prophets in the context of Nigeria." Biblical Studies and Corruption in Africa. Series Number 6:154-174. [ Links ]

Osborne, Grant R 2006. The hermeneutical spiral: A comprehensive introduction to Biblical Interpretation. 2nd ed. Illinois: Inter-Varsity. [ Links ]

Powery, Luke A 2012. Dem Dry Bones: Preaching, Death, and Hope. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/. [ Links ]

Rom-Shiloni, Dalit "Ezekiel as the Voice of the Exiles and Constructor of Exilic Ideology." Hebrew Union College Annual Vol. LXXVI (2006):1-46. [ Links ]

Schöpflin, Karin 2005. "The composition of metaphorical oracles within the Book of Ezekiel." Vestus Testamentum LV, 1:101-120. [ Links ]

Tuell, Steven 2009. Ezekiel. Michigan: Baker. [ Links ]

VanGemeren, Willem A. 1990. Interpreting the prophetic word: An introduction to the prophetic literature of the Old Testament. Michigan: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Welch, Jeffery L. "Between Text and Sermon: Ezekiel 37:1-14." Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 2016, Vol. 70(1):78-80. [ Links ]