Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.117 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/117-1-1356

ARTICLE

Christian ethics in South Africa: Liberal values among the public and elites

Hennie Kotzé1; Reinet Loubser2

Centre for International and Comparative Politics, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

This article uses statistical data from the World Values Survey (WVS) and the South African Opinion Leader Survey to examine liberal values and attitudes among the following samples of South Africans: Afrikaans, English, isiXhosa and isiZulu speaking Protestants, Catholics, African Independent Church (AIC) members and non-religious people (public and parliamentarians). We find that South Africans have softened in their traditionally conservative attitudes toward homosexuality, prostitution, abortion and euthanasia (but not the death penalty). We conclude that the South African public has gradually become more accepting of the liberal values of the constitution (the product of elite-driven transition to liberal democracy). That being said, South Africans have not become liberals as such and many mainline Protestants and members of the AICs (in particular) have remained fairly conservative in their views. Additionally, elites (parliamentarians) continue to outpace the public with regards to the acceptance of liberal values and practices.

Key words: South Africa; Christianity; Liberal Values; Human Rights

Introduction

In a previous article (Christian Ethics in South Africa: Religiosity among the Public and Elites, Kotzé & Loubser, 2017) an overview was provided of the nature and extent of religiosity among various Christian groups and non-religious people in South Africa. The present article offers an investigation into the extent to which the liberal values found in South Africa's constitution have been accepted among the same groups of people. The groups in question are Protestants, Roman Catholics, members of the African Independent Churches (AICs) and non-religious people. For a more detailed analysis, these groups are also subdivided into four language groups: mother tongue speakers of Afrikaans, English, isiXhosa and isiZulu. Wherever possible, the values of the public are compared with that of South African parliamentary leaders.

Post-Apartheid South Africa's constitution grants equal rights to all the country's citizens, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, religious affiliation or sexual orientation (see Chapter 2 of Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996:6-9). In practice, this has resulted in a series of laws that have been controversial and unpopular with the South African public. South Africa was one of the first countries to legalise same-sex marriage in 2006 despite a hostile reaction from a fairly conservative public (Thoreson, 2008; Roberts and Reddy, 2008:9-11). The acceptance of gay people as equal citizens and the practice of same-sex marriage have continued to be debated heatedly, as illustrated by the controversy and criticism provoked by the Dutch Reformed Church's decision in 2015 to admit gay members and allow them to marry in the church. This decision was under threat from the beginning and when in November 2016 the General Synod of the DRC reversed this decision, this reversal was challenged in the High Court in Pretoria. (Oosthuizen, 2015; Die Burger, 16 June 2017). The idea of gay marriage has also proved unpalatable to other churches in the country, including the Anglican Church (Laganparsad, 2016:5) and the Roman Catholic Church, both of whom criticised the initial more liberal 2015 decision of the Dutch Reformed Church (DeBarros, 2015).

Gay rights are not the only controversial moral issue where the liberal values of the constitution clash with the views of the public. The legalisation of abortion - in the name of women's rights - has also been unpopular with many South Africans (Mncwango & Rule, 2008:6-7). The passing of the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Act in 1996 provoked resistance even among many members of parliament, including members of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) who initiated the legislation under President Nelson Mandela (Guttmacher et al., 1998:193). There continues to be passionate disagreement about abortion in many sectors of South African society (Hodes, 2013; Rule, 2004:4-5). Meanwhile, advocacy groups such as SWEAT (Sex workers Educate and Advocacy Task Force) and the pro-euthanasia advocacy groups such as Dying with Dignity SA, amongst others are continuously lobbying the SA government to change the legislation regarding sex work and euthanasia.3

South African sentiments about capital punishment have been similarly contrarian. A feature of Apartheid era justice (and injustice), the death penalty was found to be unconstitutional in 1995 since it violates the rights to dignity and life (Plasket, 2006:9). The idea of capital punishment has nevertheless enjoyed a recurring popularity with many South Africans, who have been known to demand its return (Spies, 2015; Mkhondo, 2014; Nduru, 2006).

The three moral issues mentioned above - homosexuality, abortion and capital punishment - are arguably the biggest and most enduring of heated debates on values in South Africa. The country's political elites have, however, decided the matter for the public by drawing up an extremely progressive constitution, which ultimately allows the unpopular rights and restraints discussed above. This article examines what South Africans of various backgrounds (mentioned above) believe about these controversial matters in the time period 2006 to 2013 (the latter being the latest extensive data available).

In addition to South Africans' views on homosexuality, abortion and the death penalty, there is also an examination of the attitudes regarding prostitution and euthanasia. Neither have been legalised in South Africa despite debates and lobbying with regards to both (see, for example, Surujlal, J & Dhurup, M, 2009; Bateman, 2015:432-433; Slabbert & Van der Westhuizen, 2007:383-384). It is therefore important to analyse South Africans' attitudes regarding these moral dilemmas, with an eye to the future.

Data and Samples

As was the case with the first article, the World Values Survey (WVS) data (dating from 2006 and 2013) is used for statistical analysis of public beliefs and attitudes. 2 988 South Africans over the age of 16 were interviewed during the 2006 survey, while the 2013 survey included 3 531 respondents. The datasets in question are weighted to accurately reflect demographics and are also within a statistical margin of error of less than 2% at the 95% confidence level.

The South African Opinion Leader Survey (from 2007 and 2013) is used to analyse the values of South Africa's foremost opinion leaders in parliament. The former includes answers from 100 members of parliament and the latter 142.4 The surveys discussed above are administered under the auspices of the Centre for International and Comparative Politics (CICP) at Stellenbosch University. They are well-established, reputable longitudinal studies that have been conducted at regular intervals since 1981 (WVS) and 1990 (Opinion Leader Survey) respectively. The WVS is nationally representative and the results can be used to generalise about the South African public. The Opinion Leader Survey, however, is only indicative of the attitudes of some members of parliament and results from this data cannot be used to make generalisations about the South African public or elites as such.

This article studies South Africa's Christian communities and compares three categories of Christians with people who claim to have no religious denomination (described as non-religious for the purpose of this article). The different Christian denominations under investigation are Protestants, Roman Catholics and members of the African Independent Churches (AICs).5 These three denominations are the biggest religious communities in South Africa (where Christianity is also the dominant religion) (South African Institute of Race Relations, 2015:69). Other religions and denominations do not form part of this particular study and have therefore been excluded from all analyses.

To provide further insight into various South African beliefs, values and attitudes, four language groups have also been selected for closer analysis. These are the Afrikaans and English speaking communities (both being ethnically heterogeneous) as well as mother tongue speakers of isiXhosa and isiZulu (both being fairly ethnically homogenous). These are the four biggest language groups in the country,6 which is the basis for their inclusion in the study.7

The reader is kindly asked to keep the following in mind when assessing the findings: firstly, the general data on Protestants, Roman Catholics etc. includes all Protestant and Catholic etc. respondents, regardless of which language they speak. It is only the deeper analysis of language group and religion that excludes speakers of other languages; secondly, care is to be taken not to confuse language groups with ethnic groups: mother tongue Afrikaans and English speakers are not necessarily ethnic Afrikaners or people of English descent. The same may hold true for isiXhosa and isiZulu respondents, although language and ethnicity tend to overlap for the latter two groups; lastly, the sample sizes of the elites - with the exception of the Protestant elites - are quite small and this may skew the results (hence the occasional 100% agreement to a statement or question). The small sample sizes are a limitation, but the data at hand nevertheless remains the best and only source with which to learn anything about the groups in question.

Liberal Values

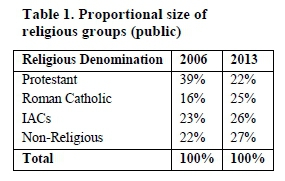

Before turning to the analysis of religion, language and liberal values, it is important briefly to note the nature of the samples in question in terms of the composition of the different religious groups. The subject is discussed in detail in Kotzé & Loubser (2017). Only the main figures are recapped in Tables 1 and 2. Do note the dramatic decrease in the proportional number of Protestants among the public.

To measure attitudes towards the controversial moral questions under investigation, respondents in all the datasets were asked whether homosexuality, prostitution and so forth are ever justifiable.8 Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the beliefs and attitudes of the public and elites regarding the values in question. A few main conclusions can be drawn: over the period 2006 to 2013 all the people in the study have grown more liberal with regards to every moral issue under investigation, with the single exception of the death penalty; secondly, despite everyone's becoming more liberal, in almost all cases the public has proven more conservative in their views than their leaders; another interesting finding is that Protestants tend to be more conservative in their views than others. This tends to be the case for both the public and elites. It should however be kept in mind that the majority of the elites are Protestant and the sample sizes of the other groups are consequently very small, which may skew the results.9 A deeper analysis according to language is provided in Table 4. It shows only the proportion of respondents who said that a given practice was never justifiable. Once again one finds that, in general, Protestants tend to be the most conservative group in the sample. In fact, they appear to have grown more conservative in many instances. In many cases AIC Christians also report fairly conservative views (even when these views are less conservative than they used to be). Among AIC members, isiZulu speakers - and sometimes also English speakers - stand out as being fairly liberal. By far the most liberal group of all is the category of English speaking non-religious people.

There appears to have been a remarkable shift in attitude towards homosexuality: it has become much more acceptable amongst almost everyone. It is only Protestants in general and Afrikaans-speaking Christians who have not softened on the subject. This probably explains the ongoing controversy over gay membership and marriage in the Protestant churches. Although the Roman Catholic Church criticised the Dutch Reformed Church's 2015 decision to be more accepting of gay people (DeBarros, 2015), its own members have in most cases become much more amenable to gay rights.

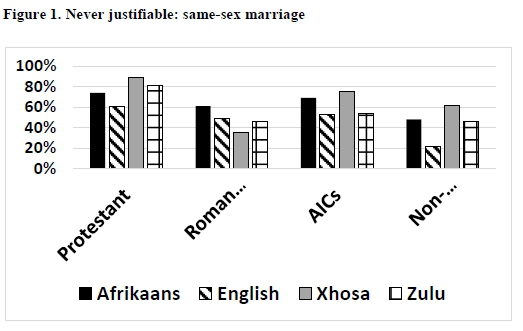

A look at the 2013 data on same-sex marriage10 confirms that most Protestants (68%) and AIC members (55%) are against the idea. However, over half of all Catholics (56%) as well as non-religious people (55%) think that same-sex marriage is sometimes or always justifiable (data not shown).

Figure 1 shows that the conservative Protestant sentiment is valid for all four language groups: over half of each group's respondents think same-sex marriage is never justifiable. AIC Christians are somewhat less conservative and Roman Catholics tend to be the most liberal of the Christians, with isiXhosa Catholics being particularly accepting of gay marriage. The most liberal group overall is non-religious English speakers, approximately 78% of whom find same-sex marriage justifiable (and most non-religious people generally agree). We found a similar pattern among elites: over half of Protestant elites (59%) are against gay marriage compared to 30% of Catholic elites and only 8% of non-religious leaders (data not shown). In addition to the decrease in disapproval of homosexuality, there is a general trend towards a more liberal attitude toward other moral and social questions. Prostitution, abortion and euthanasia have all become more acceptable in general and to specific groups in particular. However, it is important to note that although there appears to be a trend towards more liberal attitudes, the levels of acceptance among various groups differ widely on all matters. In many cases attitudes have definitely softened, but the higher levels of acceptance (of any given issue) are not necessarily high levels of acceptance as such. In many cases attitudes are still fairly conservative despite having become markedly less so since 2006. Thus one sees that most of the demographic groups in Table 4 still disapprove of everything but the death penalty.

The death penalty is the only moral dilemma where there is not a general trend towards a more liberal stance. In fact, the various demographics are divided about evenly in their respective stances on capital punishment. Discounting the demographic groups whose opinions have remained more or less the same since 2006, there are more strands of society growing increasingly in favour of capital punishment than against Table 4. In fact, isiXhosa and isiZulu speaking Protestants (and to a lesser extent isiXhosa and Afrikaans speaking AIC members) are the only people in the study with truly high levels of rejection for the death penalty. Surprisingly, English speaking non-religious people - normally a very liberal group - are the most adamantly in favour of capital punishment (only 16% think it is never justifiable). It is likely that the continued support for the death penalty in South Africa is due to the country's extremely high levels of crime and violence (Moller, 2005:268; Spies, 2015).

Factor Analysis and Moral Index

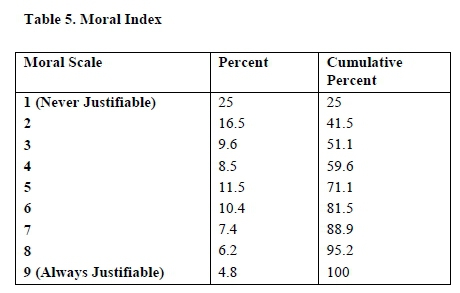

In order to construct a moral index which would indicate where the South Africans in our study can be located on a moral scale, a factor analysis was conducted (varimax rotation) on 14 items (all asking respondents about the justifiability of moral issues).11 Factor one explained 27.812% of the variance and the five items that scored highest on factor one (using a fairly high cut-off of .66) were used in the construction of the moral index. These variables were: (are the following ever justifiable:) same-sex marriage (.797), suicide (.711), homosexuality (.701), abortion (.688) and prostitution (.669).

The moral index constructed from the five variables above was recoded on a nine point scale with 1 indicating 'never justifiable' and 9 indicating 'always justifiable.' Over half of the responses were clustered around values 1-3 on the scale and approximately 60% of the variance could be found clustered around values 1-4. Most respondents therefore lean towards the disapproving side of the scale ('never justifiable'). These results merely confirm that the South Africans in our study remain quite conservative despite the effect of increased liberalism found in Tables 3 and 4 as well as Figure 1. The variance can be viewed in more detail in Table 5.

Concluding Remarks

This analysis of Christian ethics in South Africa found an important change of heart in progress: most South Africans have softened in their attitudes toward most of the controversial practices under study. This does not mean that South Africa has become a nation of liberals, but the changes that have occurred in a relatively short period of time are nevertheless remarkable and important. Where values are concerned, South Africa has been engaged in a dynamic process of change. Future analysis will reveal whether secularisation and liberalisation are set to continue.

At present it does appear as if - singular exceptions notwithstanding - the South African public is slowly being reconciled to the values of its own constitution. The constitution has largely been an elite project, initiated and implemented by South African leaders, often to an unwilling public. However, the public has not been oblivious to elites promotion of liberal values. Ordinary people have begun to grow more accepting of the sometimes offensive rights of others. Besides the influence of the value patterns among the political elite, we could only speculate why there was this slow but steady movement towards a more liberal stance on the moral issues discussed. Foremost is certainly the role of the South African Constitution and the respect that the public gained over time for the principled stance that the Constitutional Court judges took in their interpretation of important sections related to moral issues and others. The general opening up of society for debates on these issues and the influencing role of social media and advocacy groups might also have played a not insignificant part in this slow change reported in these value patterns.'

The changes occurring among Protestant worshippers were another interesting finding. South Africa's Protestant churches appear to have suffered a dramatic exodus of members (Kotzé & Loubser, 2017) and the remaining Protestant worshippers have remained remarkably conservative in the face of liberal change. If liberal values are the wave of the future, the now smaller number of Protestant worshippers appear to be quite resistant. It remains to be seen whether Protestant churches will embrace change, either for its own sake or in an attempt to win back followers. That being said, a large number of South African Christians are now affiliated with non-mainline churches such as the AICs. Respondents who belong to the AICs also often appear to be fairly conservative in their outlook.

The more detailed analysis of language communities added further perspective to the findings. Despite the recognition that English speakers have a tendency toward liberal attitudes, it is safe to say that there are considerable differences of opinion both between and within the various language groups, depending on their particular religious background as well as the particular moral dilemma with which they are presented.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bateman, C 2015. "Judge Nudges Dormant Euthanasia Draft Law" in South African Medical Journal. 105(6):432-433. [ Links ]

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. 1996. Chapter 2: Bill of Rights. Pretoria: Government Printer. 6-24. [ Links ]

DeBarros, L 2015. "NG Kerk Decision: Gay People could still Face Rejection." Mambaonline. 15 October. http://www.mambaonline.com/2015/10/15/ng-kerk-decision-gay-people-still-face-rejection/ (4 March 2016). [ Links ]

Guttmacher, S, Kapadia, F, Te Water Naude, J & de Pinho, H 2008. "Abortion Reform in South Africa: A Case Study of the 1996 Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act" in International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(4):191-194. [ Links ]

Hodes, R 2013. "Abortion in South Africa: A Conspiracy of Silence." The Daily Maverick. 30 September. http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2013-09-30-abortion-in-south-africa-a-conspiracy-of-silence/#.VssNTFJKVQ4 (22 February 2016). [ Links ]

Kotzé, H & Loubser, R 2017. "Religiosity in South Africa: Trends among the Public and Elites." Scriptura. 116, (2017:1):1-12. [ Links ]

Laganparsad, M 2016. "Church Welcomes Gay Couples but still Refuses Marriage Rites" in The Sunday Times. 28 February. 5. [ Links ]

Mkhondo, R 2014. "Let's be Democratic about Death Penalty." IOL. 29 October. http://www.iol.co.za/the-star/lets-be-democratic-about-death-penalty-1772385 (2 March 2016). [ Links ]

Mncwango, B & Rule, S 2008. "South Africans against Abortion" in HSRC Review. 6(1):6-7. [ Links ]

Moller, V 2005. "Resilient or Resigned? Criminal Victimization and Quality of Life in South Africa." Social Indicators Research. 72(3):263-317. [ Links ]

Nduru, M 2006. "Death Penalty: Calls for the Return of Capital Punishment in South Africa." Inter Press Service. 7 June. http://www.ipsnews.net/2006/06/death-penalty-calls-for-the-return-of-capital-punishment-in-south-africa/ (2 March 2016). [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, J 2015. "Gay-Besluit Gestuit." Netwerk24. 14 November. http://www.netwerk24.com/Nuus/Algemeen/gay-besluit-gestuit-20151114 (22 February 2016). [ Links ]

Plasket, C 2006. "Human Rights in South Africa: An Assessment." Obiter. 27(1):1-19. [ Links ]

Roberts, B & Reddy, V 2008. "Pride and Prejudice: Public Attitudes toward Homosexuality" in HSRC Review. 6(4):9-11. [ Links ]

Rule, S 2004. "Rights or Wrongs? Public Attitudes towards Moral Issues" in HSRC Review. 2(3):4-5. [ Links ]

Slabbert, M & Van der Westhuizen, C 2007. "Death with Dignity in lieu of Euthanasia" in SA Publieke Reg/Public Law. 22(2):366-384. [ Links ]

South African Institute of Race Relations, 2015. South Africa Survey 2015. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations. [ Links ]

Spies, D 2015. "Thousands Demand Death Penalty for Killers of Uitenhage Teacher." BizNews. 23 April. http://www.biznews.com/undictated/2015/04/23/thousands-demand-death-penalty-for-killers-of-pe-teacher/ (3 March 2016). [ Links ]

Surujlal, J & Dhurup, M 2009. "Legalising Sex Workers during the 2010 FIFA Soccer World CupTM in South Africa." African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance. September (Supplement). 79-97. [ Links ]

Thoreson, RR 2008. "Somewhere over the Rainbow Nation: Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Activism in South Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies. 34(3):679-697. [ Links ]

1 Research fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics Stellenbosch , University, hjk@sun.ac.za

2 Researcher at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics, Stellenbosch University, rloub@sun.ac.za

3 With reference to euthanasia see: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-safrica-health-euthanasia/south-africas-appeals-court-overturns-ruling-allowing-assisted-dying-idUSKBN13V1BH (downloaded 10/3/17); and with reference to SWEAT see: http://www.sweat.org.za/

4 In the 2007 data set, approximately 52% of respondents were members of the ANC, 25% were DA members and 7% belonged to the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). The rest of the sample belonged to various other small parties. In 2013 approximately 44% of the members of parliament interviewed belonged to the ANC, 41% to the DA, 10% to the Congress of the People (COPE) and 5% to the IFP. The samples were not weighted and are not representative of each political party's proportion of seats in the national assembly.

5 AIC members are excluded from the analysis of elites as there are too few parliamentarians who belong to this denomination to make statistical analysis feasible.

6 According to the 2011 census, isiZulu has 11 587 374 mother tongue speakers, followed by isiXhosa (8 154 258), Afrikaans (6 855 082) and English (4 892 623) (Statistics South Africa, 2011:23).

7 It is only with the public data from the WVS that it is possible to analyse language groups. The sample sizes of the elite data are too small to make statistical analysis feasible. There is therefore no subdivision of the elites into language groups.

8 Respondents answered the questions on a ten point scale with 1 indicating 'Never' and 10 indicating 'Always.' The ten point scales were recoded to provide three response categories: 'Never' (values 1-4 were recoded as 1), 'Sometimes' (values 5-6 were recoded as 2) and 'Always' (values 7-10 recoded as 3).

9 The small sample sizes can probably also be the reason why much of the elite data is not statistically significant. This means that there is a chance that the pattern of response is merely due to chance and does not necessarily indicate a significant pattern. Data that is not statistically significant (indicated with an *) is therefore not usable.

10 The question over the justifiability of same-sex marriage was only included in the 2013 WVS and there is thus no 2006 data.

11 The factor analysis and moral index were done only with the WVS's 2013 data.