Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.116 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/116-2-1320

ARTICLES

The metaphorical depiction of Nineveh's demise. The use of the locust 'marked metaphor' in Nahum 3:15-171

Willie Wessels

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The passage Nahum 3:15-17 operates within a context in which the theme of destruction is expounded. Various references of locusts as part of simile are used to speak about the threat and downfall of Nineveh, the symbol of Assyrian power, and some of its influential people. The article aims not only to to discuss the various applications of the locust metaphor in the designated verses, but also to argue how this metaphor is used effectively to speak mockingly about the dreaded power of Assyria, symbolised by Nineveh, her officials and people. In this article, the effective use of the locust 'marked metaphor' is discussed in an attempt to illustrate to the vulnerability and fleeting nature of the power of the once dominant Assyria. The oracle functions to encourage the people of Judah to envisage a display of Yahweh's power to cause the downfall of the enemy.

Key words: Nahum; 'Marked Metaphor'; Locust; Nineveh; Power

Introduction2

In the book of Nahum conflict between two major powers is displayed. Yahweh is presented as the Sovereign power dealing with the Assyrians as a dominant world power in the history of Judah. The content of Nahum is both fascinating and disturbing. The language, rhetoric and imagery grasp the attention of readers of the Nahum text. The text not only appeals to the imagination of the aggrieved and dominated people of Judah, but also to generations of readers and exegetes of the Nahum text. As mentioned, the text of Nahum is disturbing for reason of its vivid and graphic depiction of scenes of violence and derogatory language regarding women. A balanced engagement with the text of Nahum will have to deal with both of these prominent characteristics of the book. This article has an interest in the use of the locust metaphor in Nahum 3:15-17 in terms of responding to Assyria's power dominance.

I have observed that in Nahum 3:15-17 several references to locusts are used to refer to Nineveh and various people that embody the imperial power Assyria. The references to locusts are used as similes ('marked metaphors') to convey certain views about the Assyrian power in a rhetorically deliberate manner.

The question this article wants to explore is how the observed characteristics and behaviour of locusts are related to the imperial power as represented by Nineveh and its leaders.

The passage will first be analysed by performing a close reading of the text, before being interpreted to present a comprehensive understanding of the passage. In the process, relevant literature will be consulted to support views and broaden the discussion.

Demarcation of the Text

Nahum 3 is a chapter that addresses the city of Nineveh for the larger part, with verse 18-19 addressed to the King of Assyria. Chapter 3: 1 introduces a new section with a cry of lament ( ) over Nineveh. Nahum 3:7 concludes a first person speech of Yahweh that commenced in verse 5. A new subsection starts in 3:8 with a question directed at the city Nineveh and continues up to verse 17. Within the section Nahum 3:8-17, smaller sub-divisions can be made in verses 8-12 and 13-17. The section in 3:13 is introduced by the interjection

) over Nineveh. Nahum 3:7 concludes a first person speech of Yahweh that commenced in verse 5. A new subsection starts in 3:8 with a question directed at the city Nineveh and continues up to verse 17. Within the section Nahum 3:8-17, smaller sub-divisions can be made in verses 8-12 and 13-17. The section in 3:13 is introduced by the interjection  (behold, surely). This section continues up to verse 18 where there is a change in the pronouns from second person singular feminine, referring to Nineveh, to second person singular pronouns, referring to the King of Assyria. The division of chapter 3 can then be regarded as follows:

(behold, surely). This section continues up to verse 18 where there is a change in the pronouns from second person singular feminine, referring to Nineveh, to second person singular pronouns, referring to the King of Assyria. The division of chapter 3 can then be regarded as follows:

1. 3:1-7 Threatening speech about Nineveh

2. 3:8-17 Defencelessness of Assyria

3. 3:18-19 Satirical song about Nineveh

The focus of this article is on Nahum 3:15-17 within the context of the larger section 3:8-17. The passage 3:15-17 functions within a context where the defencelessness and destruction of Nineveh is emphasised. Although the oracle has the purpose to install trust in Yahweh's power, rhetorically it is presented as an address to Nineveh and its officials.

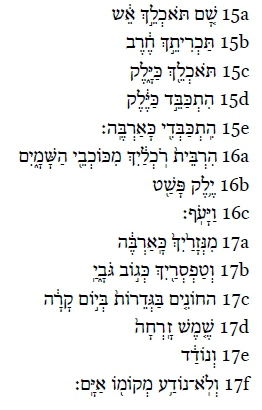

Presentation of the text of Nahum 3:15-17

Before a discussion of the text is offered, it is necessary to engage some theoretical aspects regarding simile and metaphor.

Theoretical Remarks on Simile and Metaphors

In Nahum 3:15-17 the literary form involving the various references to locusts is a simile. When a simile is used, two entities are compared by means of a word such as 'like.' These entities can be objects, people and even ideas. There is some form of expectation from the side of the author that the audience or readers can in some way relate to the components of the simile.3

Metaphors differ from simile in that the comparative words such as 'like' and 'as' are not used, but that the one object is the other one. Loader4 expands on this by explaining that in a metaphor of the two elements mentioned, the one element is more concrete and the other more abstract. In an attempt to define metaphors and simile, Jindo5 states that a simile is:

a non-literal comparison introduced by like or as. A simile is also a metaphor, whereby one thing is understood and described in terms of another. The difference between simile and metaphor is rhetorical in that simile are less direct and less emphatic than the corresponding metaphor.

In this study, I am not so much concerned about the fine distinction that is made between a metaphor and a simile, since both of these literary forms appeal in some or other way to the imagination of the audience or the reader. My approach to the book of Nahum is that the emphasis should be on the poetic nature of the text by means of which the author of the text wants to appeal to the imagination of the people of Judah as first receivers of the oracles, to create an imaginative reality of the downfall of the Imperial oppressor.6 The appeal of the author is to people who are feeling dismayed, to see in their mind's eye how Yahweh, the supreme power, will annihilate the power of the oppressor.

In a study on animal metaphors in the book of Lamentations, Labahn7 explains her methodological approach to the terminology of metaphor and simile. She has indicated in her research that some of the animal metaphors are in reality in the form of similes. She refers to these similes as 'marked metaphors,' explaining that they share 'the same intention as metaphors without markers'8 In his discussion of similes and metaphors, Tate9 has made it clear that the two objects of components of a simile or even a metaphor should be familiar to the experience of the audience in order for them to be able to relate to the metaphor or simile. He states in this regard:

Indeed, if the reader does not hold a body of information in common with the author, the hyperbole may not have its desired effect. The same is true for simile and metaphor. Both forms are comparative figures of speech; i.e., simile and metaphor require that a reader compare two objects that are in real life incongruous.10

In her approach to the various components of a simile or a metaphor, Labahn11 argues that they have polyvalent meanings and 'generate various ways of understanding and interpreting their meanings.' The interplay between the metaphors and the hearers or readers contributes to the creation of meaning. It is also true that language is needed to give expression to the elements of a simile or a metaphor. Language in this sense is also restrictive in that:

Language denotes a metaphor in a certain way; however, language is bound to a specific sociological and cultural framework. Hence, the language of a particular metaphor has to be common to the sociological framework of its hearers and readers. Their environment enables them to decode a possible meaning of a metaphor and to adapt it to their specific situation.12

Cognitive linguistics has presented new insights when referring to metaphors and this will apply equally to simile as well. The view is that mental concepts are formed in our minds and language is the vehicle through which we express them. Language is the tool that enables us to communicate, but the meanings we form are based on the mental concepts formed in our minds. The usual way of looking at metaphors is to regard them as stylistic devices, but the discussion here is interested in the conceptual structures underlying metaphors and similes. Dobric maintains that 'metaphorical concepts represent interwoven basic structures of human thought, social communication and concrete linguistic manifestation through a rich semantic system based on the human physical, cognitive and cultural experience.'13

Following this line of thinking about metaphors, Jindo has argued that a metaphor, however, can also function as 'a representational component, as a mode of orientation'14 He continues by saying that a metaphor can be very valuable as a creative component, 'as a means to convey a poetic insight.'15 This article is interested in the underlying cognitive concepts that the poet or writer wanted to reveal or disclose by using the locust metaphors. The question is, what mental pictures are formed characteristic of locusts when the poet in Nahum uses the various words or concepts to refer to them? What mental associations does the author want his audience or readers to make when he uses the various words for locusts to say something about Nineveh and the leaders (officials) he relates to these mental constructs?

In metaphor theory, the language used is to speak of a source conceptual domain and a target conceptual domain.16 The source domain is concrete whilst the target domain is more abstract. In terms of the locust metaphor (simile), the concept of the locust would be the concrete source domain that is transferred onto the more abstract target, in this case, a city and people. Basson expresses the view that conceptual metaphor theory suggests that our most highly structured experiences are with the physical world and the patterns we encounter and develop through interaction of our bodies with the physical environment serve as our most basic source domains.'17 This is obviously the case in Nahum 3:15-17 where the source domain is the authors' exposure to the physical environment that hosts the locusts.

The approach in this article is to analyse the various components that form the similes ('marked metaphors') in which there are references to the locusts and secondly to determine the function of the insect metaphors within the sociological context presupposed of Nahum.

Observations and Explication of the 'Marked Metaphor' (Simile) Components

Three different nouns for locusts are used in verses 15-17. The question is, what do we know about these locusts and what are the significant characteristics we know about these creatures that contribute to the point the author wants to make regarding Nineveh and the people in Nineveh?

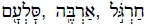

It was stated that the interest of this article is the use of simile to draw comparisons between situations and persons or key personnel in the administration of the government in Nineveh and various forms of locust species or phases in their life cycles. The comparisons revealed that the author made some perceptive observations regarding the locusts ( ):They devour, they multiply (v. 15), they shed skin and they fly away (v. 16). With regards to the adult locusts (

):They devour, they multiply (v. 15), they shed skin and they fly away (v. 16). With regards to the adult locusts ( ): they multiply (v.15), they sit static on fences in the cold (v. 17) and with regards to the swarm of locusts ('

): they multiply (v.15), they sit static on fences in the cold (v. 17) and with regards to the swarm of locusts (' ): they fly (flee) away when the sun rises.

): they fly (flee) away when the sun rises.

The counterpart (target) of the 'marked metaphor' in verse 15 is the city Nineveh (2ndperson feminine singular suffix). In 16a the merchants in Nineveh are in focus. If 16b and c are regarded as a continuation of 16a, then they are related to the locust that sheds its skin and flies away. In this regard, no 'marked metaphor' is in play, only an allusion to how locusts behave. In Nahum 3:17 the counterparts of the locust metaphors ( and

and  ) are respectively the guards/courtiers and the scribes of Nineveh and the rest of the verse explains where the comparison lies.

) are respectively the guards/courtiers and the scribes of Nineveh and the rest of the verse explains where the comparison lies.

As mentioned, the approach I have advanced about the book of Nahum is that the poetic nature of the text is the key to understanding the book. The author throughout the book appeals to the imagination of the people to envision a reality other than what they experience by the hand of the oppressive imperial power.18 Metaphors are essential for the author in creating this imaginative appeal. The locust 'marked metaphor' is one example of this appeal to the imagination of the people of Judah and later generations interpreting Nahum in their contexts.

Brief Description of Text Related Matters

From the outset in verse 13 a second female subject is addressed. The book of Nahum has made it clear that Nineveh is implied here. Verses 13 and 14 sketch a scene of vulnerability by labelling the people of the city as women to depict weakness. They also describe the land as open, thus defenceless to the enemy and the gate bars as susceptible to fire. Verse 14, in typical Nahum style, uses imperatives such as draw, strengthen, trample, tread and make - to heighten the urgency of preparation of defences to protect the city against the enemy (cf. 2:3-5).

What follows in verse 15 is a depiction of the futility of all efforts to safeguard the city. Three verbs expressing strong destructive actions are used to describe extremely negative consequences for Nineveh. The verbs are: to devour, to cut off/down and again to devour. To make it worse, these three verbs are respectively linked to the nouns fire, sword and locust. In 15b it is stated that the sword will destroy (cut down) Nineveh (2nd person feminine singular), followed in 15c explaining that the sword (feminine noun) will devour Nineveh like a locust does. Surprisingly, these strong destructive depictions are followed by two imperatives of the same Hithpael form of the verb  , however, the first imperative masculine and the second feminine, to multiply. The call in the first instance is to multiply like the locust, referring to the noun

, however, the first imperative masculine and the second feminine, to multiply. The call in the first instance is to multiply like the locust, referring to the noun  , and the second instance to multiply like the adult locust, referring to the noun

, and the second instance to multiply like the adult locust, referring to the noun  . The contrasting descriptions of total destruction and then the call to multiply are peculiar and will be addressed later.

. The contrasting descriptions of total destruction and then the call to multiply are peculiar and will be addressed later.

Verse 16 continues addressing the city. The verb 'to increase' is used here to refer to the increasing of the numbers of the merchants in Nineveh, as vast as the stars of the heaven.

This is followed by the seemingly unrelated reference to the locust ( )that sheds its skin (

)that sheds its skin ( )and flies away (

)and flies away ( ). Spronk19 has offered a detailed discussion of the problem of relating the star metaphor of 16a with the reference to the locust metaphor introduced in 3:16b and c and 17a. He regards this as an early interpretive addition to the existing text and relates it to Babylon. Bosnian20 agrees with Spronk on this suggested insertion as a first text reinterpretation of the Nahum text. There is some logic in the suggested interpretation, but even if it is an explanatory insertion in the Nahum text, the metaphor (simile) of the locust makes sense in the context of the threat posed to Nineveh and the described actions and reactions of key figures in the royal administration in Nineveh. When the heat of the threat of invasion reaches the officials in Nineveh, they are not sources of strength, but will abandon the city. It seems possible to apply what is understood by the locust as one component of the metaphor to the other component of the metaphor as it relates to Nineveh and her officials in the context of a threat to the city by an enemy. The verb

). Spronk19 has offered a detailed discussion of the problem of relating the star metaphor of 16a with the reference to the locust metaphor introduced in 3:16b and c and 17a. He regards this as an early interpretive addition to the existing text and relates it to Babylon. Bosnian20 agrees with Spronk on this suggested insertion as a first text reinterpretation of the Nahum text. There is some logic in the suggested interpretation, but even if it is an explanatory insertion in the Nahum text, the metaphor (simile) of the locust makes sense in the context of the threat posed to Nineveh and the described actions and reactions of key figures in the royal administration in Nineveh. When the heat of the threat of invasion reaches the officials in Nineveh, they are not sources of strength, but will abandon the city. It seems possible to apply what is understood by the locust as one component of the metaphor to the other component of the metaphor as it relates to Nineveh and her officials in the context of a threat to the city by an enemy. The verb  however, can also have the meaning 'to dash off.' What is implied here will be discussed in the sections to follow.

however, can also have the meaning 'to dash off.' What is implied here will be discussed in the sections to follow.

In verse 17 comparisons are made to key persons in the administration of the city Nineveh. In the first instance, guards/courtiers ( )21 are compared to locusts (

)21 are compared to locusts ( ) and in the second instance scribes (

) and in the second instance scribes ( )22 are compared to swarms of locusts (

)22 are compared to swarms of locusts ( ). Verse 17 describes the practices of these locusts - they sit on fences when it is cold and when the sun rises, they become active and fly away to unknown destinies.23 What is of interest here is the repeated use of the preposition

). Verse 17 describes the practices of these locusts - they sit on fences when it is cold and when the sun rises, they become active and fly away to unknown destinies.23 What is of interest here is the repeated use of the preposition  in drawing comparisons with entities related to the city and species or life cycles of locusts. It is more likely that the references are to the life cycle of locusts.

in drawing comparisons with entities related to the city and species or life cycles of locusts. It is more likely that the references are to the life cycle of locusts.

The Various Uses of and in the Old Testament

The Israelites knew at least nine distinct species of locust. It should however, be acknowledged that some of the nouns referring to locusts might indicate phases in the life cycle of locusts rather than species. Considering the list of food allowed to be eaten, Leviticus 11:22 names four locusts, namely  ,

,  , as constituting clean locusts which probably indicate that they are four distinct species. On the other hand, Joel 1:4 mentions four locusts as well, namely,

, as constituting clean locusts which probably indicate that they are four distinct species. On the other hand, Joel 1:4 mentions four locusts as well, namely,  , and

, and  . These may be four distinct species, but it probably refers to four various stages in locust development.24 In Nahum 3:15-17, three nouns are used to refer to locusts. What follows is an overview of the uses of these nouns in the Old Testament.

. These may be four distinct species, but it probably refers to four various stages in locust development.24 In Nahum 3:15-17, three nouns are used to refer to locusts. What follows is an overview of the uses of these nouns in the Old Testament.

in the Old Testament

in the Old Testament

This word appears nine times in the Old Testament, in Psalm 105:34; Jeremiah 51:14, 27; Joel 1:4 (twice), 2:25 and Nahum 3:15 (twice), 16.

Psalm 105:34 calls to memory the situation of oppression in Egypt and Yahweh's action in freeing the Israelites from Egyptian bondage. Two words for locusts ( )are used depicting his actions. Translators differ on how to translate these two words, but the distinction is not that important in this context. Verse 34 states that Yahweh is calling them up for the reason stated in verse 35, namely to devour all the vegetation of the land and to eat all the fruit of the land. Two things are important here, namely the emphasis on the vast numbers of the locusts and secondly the use of the verb 'to eat' (

)are used depicting his actions. Translators differ on how to translate these two words, but the distinction is not that important in this context. Verse 34 states that Yahweh is calling them up for the reason stated in verse 35, namely to devour all the vegetation of the land and to eat all the fruit of the land. Two things are important here, namely the emphasis on the vast numbers of the locusts and secondly the use of the verb 'to eat' ( ) twice. The image this calls to mind is that swarms of locusts devour all that has been planted and produced by the land. This image is similar to what we find in Nahum 3:15 where the same verb 'to eat' (

) twice. The image this calls to mind is that swarms of locusts devour all that has been planted and produced by the land. This image is similar to what we find in Nahum 3:15 where the same verb 'to eat' ( is used to describe what locusts can do.

is used to describe what locusts can do.

The reference in Jeremiah 51:14 concerns the downfall of Babylon; the locust simile again creates the image of a multitude of people that will invade the city.

Jeremiah 51:27 refers to a battle scene against Babylon, in which the image is of horses that behave in a manner resembling large numbers of locusts swarming around. What is also interesting is the use of the word  , referring to a 'marshal/commander' in a military context. This word is also used in the plural in Nahum 3:17 in reference to some officials in Nineveh that are compared to locusts.

, referring to a 'marshal/commander' in a military context. This word is also used in the plural in Nahum 3:17 in reference to some officials in Nineveh that are compared to locusts.

In Joel 1:4 both words referring to locusts ( and

and  ) are used twice to describe a situation where these insects have stripped the land of its produce. In verse 6 it is mentioned again that large numbers of the enemy, similar to swarms of locusts, have invaded Jerusalem. In an important footnote, the translators of the JPS Hebrew-English TANAKH remark that 'The Heb. terms translated "cutter, locust, grub, and hopper" are of uncertain meaning; they probably designate stages in the development of the locust' (JPS 1999:1299 note a).

) are used twice to describe a situation where these insects have stripped the land of its produce. In verse 6 it is mentioned again that large numbers of the enemy, similar to swarms of locusts, have invaded Jerusalem. In an important footnote, the translators of the JPS Hebrew-English TANAKH remark that 'The Heb. terms translated "cutter, locust, grub, and hopper" are of uncertain meaning; they probably designate stages in the development of the locust' (JPS 1999:1299 note a).

In the reference in Joel 2:25, both the nouns  and

and  are used to refer to the locusts. It is used in this context with the verb 'to eat' (

are used to refer to the locusts. It is used in this context with the verb 'to eat' ( Qal) similar to Nahum 3:15 to indicate the damage the locusts caused by eating what was produced on the fields.

Qal) similar to Nahum 3:15 to indicate the damage the locusts caused by eating what was produced on the fields.

The last two occurrences of  are in Nahum 3:15 and 16 which will be discussed in more detail in this article.

are in Nahum 3:15 and 16 which will be discussed in more detail in this article.

in the Old Testament

in the Old Testament

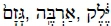

There are twenty-four references to  in the Old Testament. Six of these texts refer to locust as simile, using the word 'arbeh (

in the Old Testament. Six of these texts refer to locust as simile, using the word 'arbeh ( ). These are Judges 7:12; Job 39:20; Psalm 109:23 and Nahum 3:15, 17. Judges 7:12, and so also 6:5, are used as metaphors, depicting the vast number of Midianites and Amalekites invading the land. Job 39:20 relates a comparison between a horse and the leaping movement of a locust from Yahweh's whirlwind speech. In Psalm 109:23 the comparison is between a human and a locust to indicate the insignificance of a human being.

). These are Judges 7:12; Job 39:20; Psalm 109:23 and Nahum 3:15, 17. Judges 7:12, and so also 6:5, are used as metaphors, depicting the vast number of Midianites and Amalekites invading the land. Job 39:20 relates a comparison between a horse and the leaping movement of a locust from Yahweh's whirlwind speech. In Psalm 109:23 the comparison is between a human and a locust to indicate the insignificance of a human being.

The word  as a noun is used in Exodus 10:4; 12-14; 19 to describe the eighth plague of locusts in Egypt. In Deuteronomy 28:38; 1 Kings 8:37; 2 Chronicles 6:28 (a nearly verbatim repetition of 1 Ki 8:37); Psalm 78:46; Joel 1:4; 2:25 and in Nahum 3:15; 17

as a noun is used in Exodus 10:4; 12-14; 19 to describe the eighth plague of locusts in Egypt. In Deuteronomy 28:38; 1 Kings 8:37; 2 Chronicles 6:28 (a nearly verbatim repetition of 1 Ki 8:37); Psalm 78:46; Joel 1:4; 2:25 and in Nahum 3:15; 17  refers to a devouring plague as well. In Jeremiah 46:23 Yahweh accentuates the innumerability of Judah's enemies by comparing them with grasshoppers. Proverbs 30:27 depicts the enormity of a swarm of locusts. Psalm 105:34 states that Yahweh creates locusts by speech and sends them forth (see the use in combination with

refers to a devouring plague as well. In Jeremiah 46:23 Yahweh accentuates the innumerability of Judah's enemies by comparing them with grasshoppers. Proverbs 30:27 depicts the enormity of a swarm of locusts. Psalm 105:34 states that Yahweh creates locusts by speech and sends them forth (see the use in combination with  already mentioned). In the final instance, Leviticus 11:22 offers a general description of locusts, especially with the view to distinguishing which may be eaten.

already mentioned). In the final instance, Leviticus 11:22 offers a general description of locusts, especially with the view to distinguishing which may be eaten.

in Nahum 3:17

in Nahum 3:17

The noun  is found in Amos 7:1 and Nahum 3:17 only. The meaning of the noun is unclear, but it seems to refer to a collective of locusts, thus indicating a swarm of locusts.

is found in Amos 7:1 and Nahum 3:17 only. The meaning of the noun is unclear, but it seems to refer to a collective of locusts, thus indicating a swarm of locusts.

Summary Observations

Of the three nouns used referring to locusts in Nahum 3:15-17,  is the one most often used (24 times).

is the one most often used (24 times).  . is used nine times and

. is used nine times and  only twice in the Old Testament. The various Bible translations are also not of great help, since they differ on how to translate the Hebrew words

only twice in the Old Testament. The various Bible translations are also not of great help, since they differ on how to translate the Hebrew words  and

and  referring to species or life phases of the locust. Ryken et al. remark, 'Locusts were voracious at all three stages of their development - a larval stage in which wingless locusts hop like fleas, a pupal stage in which the wings are encased in a sack and the locusts walk like ordinary insects, and the adult stage in which they fly.'25 It seems from the various uses of

referring to species or life phases of the locust. Ryken et al. remark, 'Locusts were voracious at all three stages of their development - a larval stage in which wingless locusts hop like fleas, a pupal stage in which the wings are encased in a sack and the locusts walk like ordinary insects, and the adult stage in which they fly.'25 It seems from the various uses of  . and

. and  that the first noun most probably refers to the nymph phase in the development of locusts, while the second word probably has the adult locust with wings in mind.26 In Nahum 3:16 it is said that the

that the first noun most probably refers to the nymph phase in the development of locusts, while the second word probably has the adult locust with wings in mind.26 In Nahum 3:16 it is said that the  sheds skin and then flies away, meaning that after shedding skin the locust enters a next developmental phase which allows for flying. There is more uncertainty when it comes to the use of which

sheds skin and then flies away, meaning that after shedding skin the locust enters a next developmental phase which allows for flying. There is more uncertainty when it comes to the use of which  occurs only in Amos 7:1 and Nahum 3:17. It seems more suitable to settle for a meaning for

occurs only in Amos 7:1 and Nahum 3:17. It seems more suitable to settle for a meaning for  as a swarm of locusts, therefore a collective word for a multitude of locusts.

as a swarm of locusts, therefore a collective word for a multitude of locusts.

An Integrative Interpretation of Nahum 3:15-17 in the Context of 3:8-17

In verses 8-17 the defencelessness of Nineveh is the subject. In the first three verses (8-10) named cities and places are mentioned. Verse 8 mentions No-Amon, situated on the Nile. This is most probably a reference to Thebes, one of the greatest Egyptian cities.27 It had particular religious significance because it housed the sanctuary of the god Amon. This city was well-located on the Nile and surrounded by water, well-fortified and regarded as a powerful city. This city seemed invincible, but eventually fell victim to the onslaught of the Assyrian army in 663 BCE and was captured. In verse 8 the rhetorical question is directed to Nineveh, whether she regards herself as better than Thebes, especially when Thebes' strategic position is considered. At this stage, Assyria was probably still in power and dominating the nations. Thebes did not survive military attack at the hands of the Assyrians; the question then is, why is Nineveh so arrogant to think that she is better off than Thebes? The sceptics of Judah who had similar thoughts of how impossible it would be to defeat Nineveh should reconsider, because Yahweh has the power to accomplish what he has set out to do.

Verse 9 continues with the thoughts about Nineveh's invincibility by referring to Cush (Ethiopia) and Egypt as sources of strength to Thebes (cf. Ps. 68:31). To add to that, Put and Libya are also seen as allies of Thebes. This all serves the purpose of demonstrating how powerful Thebes has been. Although the precise geographical location of these places is difficult to determine, they serve the purpose of emphasising Thebes' strength because of these allies.28 The mentioning of these places serves a literary purpose in order to heighten the comparison between Thebes and Nineveh. Thebes' powerful position however, was not enough to safeguard the city from defeat,29 on what grounds then is Nineveh better off?

Verse 10 draws a conclusion about Thebes' situation. It is, however, more important to draw the intended conclusion for which Thebes serves as an example - what will happen to Nineveh? Thebes suffered defeat and was taken into exile. To prevent the possibility of a future generation for the people of Thebes, her infants were brutally killed '...dashed to pieces at every street corner'. The lot was cast for the nobility of Thebes probably to decide who their slave-owners would be (cf. Joel 3:4) and then they were put in chains (cf. Ps. 149:8; also Isa. 45:14). This depicts Thebes as powerless with no future prospects. In the light of what happened to Thebes, the question to Nineveh in verse 8 should be repeated: 'Are you better than Thebes...?'

Verse 11 commences with the words 'you too' ( )with the

)with the  repeated in the same sentence. The same happens in verse 10 which is also introduced with and then followed by another

repeated in the same sentence. The same happens in verse 10 which is also introduced with and then followed by another  . This serves as a definite link between the verses showing that Nineveh will suffer a similar fate as Thebes, their enemy. Thebes was not invincible, neither is Nineveh. It is not exactly clear what is meant by the expression that 'you too will become drunk'. Perhaps it should be understood as a reaction of despair to the reality that they will not escape Yahweh' s wrath. Many people become drunk as a means to escape reality. Is that what will happen to Nineveh too? They will seek to escape by hiding from their enemy. This will not, however, serve as an escape from Yahweh's power, because he is sovereign and will not tolerate Nineveh's oppression of his people, namely Judah. Yahweh's people take refuge in him, but the enemy of his people will not find refuge, they will be destroyed.

. This serves as a definite link between the verses showing that Nineveh will suffer a similar fate as Thebes, their enemy. Thebes was not invincible, neither is Nineveh. It is not exactly clear what is meant by the expression that 'you too will become drunk'. Perhaps it should be understood as a reaction of despair to the reality that they will not escape Yahweh' s wrath. Many people become drunk as a means to escape reality. Is that what will happen to Nineveh too? They will seek to escape by hiding from their enemy. This will not, however, serve as an escape from Yahweh's power, because he is sovereign and will not tolerate Nineveh's oppression of his people, namely Judah. Yahweh's people take refuge in him, but the enemy of his people will not find refuge, they will be destroyed.

The simile in verse 12 is a fig tree carrying early ripe figs. These figs are obtained earlier than the normal collecting time of the other figs and they are eaten swiftly (cf. Isa. 28:4). The figs probably refer to the fortresses that protect the city wall and the gates of Nineveh.30 To continue the simile the picture created is of figs falling from the tree when it is shaken. Nineveh will fall like a ripe fig into the mouth of the eater, her attacker and enemy. The city will offer very little resistance to the invading enemy.

Verse 13 is introduced by a call to pay attention ( )to the morale of Nineveh's troops. They are like women, an image applied to denote a lack of courage and weakness (cf. Isa. 19:16; Jer. 50:37, 51:30). The once mighty army is now regarded as powerless. The use of metaphors that are derogatory to women needs to be treated with great sensitivity. It is to be understood within the social context that gave rise to such images, but it becomes dangerous when it leads to the creation of stereotypes.31 The real challenge is to create new metaphors in current contexts that convey the essence of the redundant ones. The second image is a land in which the gates are wide open and, therefore, offers easy access to the enemies. Fire has consumed the bars of the gates. Because of the weakness of the soldiers, there is no defence and no resistance to invaders. The image of 'gates of a land' is somewhat strange, but the meaning is clear that the access to the land is so free as though gates are open (cf. 2:7 in this regard).

)to the morale of Nineveh's troops. They are like women, an image applied to denote a lack of courage and weakness (cf. Isa. 19:16; Jer. 50:37, 51:30). The once mighty army is now regarded as powerless. The use of metaphors that are derogatory to women needs to be treated with great sensitivity. It is to be understood within the social context that gave rise to such images, but it becomes dangerous when it leads to the creation of stereotypes.31 The real challenge is to create new metaphors in current contexts that convey the essence of the redundant ones. The second image is a land in which the gates are wide open and, therefore, offers easy access to the enemies. Fire has consumed the bars of the gates. Because of the weakness of the soldiers, there is no defence and no resistance to invaders. The image of 'gates of a land' is somewhat strange, but the meaning is clear that the access to the land is so free as though gates are open (cf. 2:7 in this regard).

Verse 14 returns to the by now familiar way the poet expresses himself. By means of short commands (imperatives), there is a fast flow of scenes that involve the audience as they see different actions taking place. The poet succeeds in creating an atmosphere of urgency. Han remarks that 'The continuing sarcasm in the imperatives can hardly be missed.'32 He explains by saying that the imperatives are in feminine form and meant to be derisive. Nineveh should prepare for the imminent siege to take place, therefore she should secure water supplies and strengthen her defences. To have strong fortifications they need to do the necessary repair work and the strengthening of it. For this purpose, they have to 'work the clay, tread the mortar and to take hold of the brick-mould'. But there is irony in this encouragement to strengthen their fortifications, because it is a useless exercise.33There should be no doubt, Nineveh will be destroyed by fire and their efforts will come to nothing. The fortifications that were supposed to protect them will, once they are burned down, instead become a threat to them.34

Verse 15 announces destruction. All the preparations of verse 14 will come to nothing. The poet indicates three ways the destruction will be accomplished. In all probability, these means of destruction should be taken figuratively as a way of poetic expression and not literally, although the possibility cannot be ruled out. The three ways are: Fire that will devour Nineveh, a sword will cut her off and as young locusts consume a field, Nineveh will be consumed by the invading enemy (cf. sword). In this regard Han interestingly states: 'The prophet's catalogue of instruments of execution includes not only the fire and sword already mentioned in the book (cf. 2:3, 13), but also the locusts, which devastate the land.'35 It is clear that Nineveh is facing certain destruction. Nogalski36 regards the inclusion of the reference to  (locust) in Nahum 3:15 due to influence from the book of Joel. There is no reason to draw this conclusion, since the devastating effect of locust surely was a known phenomenon37 and the comparison to the destructive consequences of an invading army makes sense. Vermeulen remarks that 'The simile with the enemy draws on the rapacious hunger of locusts, while that with the city draws on the rapid multiplication of the creatures.'38

(locust) in Nahum 3:15 due to influence from the book of Joel. There is no reason to draw this conclusion, since the devastating effect of locust surely was a known phenomenon37 and the comparison to the destructive consequences of an invading army makes sense. Vermeulen remarks that 'The simile with the enemy draws on the rapacious hunger of locusts, while that with the city draws on the rapid multiplication of the creatures.'38

Interestingly, in the second half of the same verse the image of the locusts is continued, but with a different purpose in mind. The inhabitants of Nineveh are encouraged to multiply like young locusts, and to add emphasis, to multiply like locusts. The emphasis seems to be on the numbers here.39 These last commands express bitter irony: Multiply, yes multiply! This will all come to nothing, for Yahweh will destroy them irrespective of power or of numbers. The use of the metaphor of locusts in this verse and in the verses to come has an ironic purpose. At first, it is used to describe the destructive result of the invading enemy on the city. Then the people of Nineveh are encouraged to multiply in numbers as locusts would (the same Hebrew word for locust is used) as a defence mechanism. However, numbers will not render the expected result, for Yahweh will see to it that it comes to nothing.40 Both references to the locust will, therefore, have the same negative result.

Verse 16 continues the irony of verse 15. Though Nineveh multiplies her merchants till they are more than the stars in heaven, it is worth nothing. The prosperity that lively trade brings to the city and all that accompanies it, wealth, security and confidence will not last.41The merchants will exploit the situation as long as it suits their purposes, then like a locust42strips the land, spreads its wings and flies away, they will depart.43 O'Brien44 regards this as an image of 'cowardly retreat.' The contribution of the merchant is no source of security to rely on, but is temporary in nature. Nineveh will, therefore, experience military destruction from the outside, but at the same time social self-destruction from the inside because of self-serving people.45

Verse 17: The simile employing the image of locusts is continued in this verse with the same purpose of expressing instability and insecurity. First Nineveh's guards46 are compared with locusts and her officials/scribes with swarms of locusts. They are depicted as sitting on the fences/walls or a hedge on cold days, but when the sun comes out and it gets warmer, they fly away. To emphasise their unreliability it is said that they not only fly away, but they disappear and no one knows where they have gone.47 The idea is also raised that the rising of the sun should be associated with the appearance of Yahweh.48 When he appears in power, those in power (the officials) in Nineveh will back off and disappear.

Function of the 'Marked Metaphors' in Nahum 3:15-17 with regards to Power

The question this article wanted to address was how the observed characteristics and behaviour of locusts are related to the imperial power of Nineveh and its leaders.

It is clear that Nahum 3:8-17 concerns the defencelessness of Nineveh in spite of its defence systems and the high profile people inhabiting the city. These components were supposed to represent the power and strength of the Assyrian nation and its leaders. However, this passage contains a taunt of the city as a power base, inhabited by people, leaders and administrators.49 In the whole process, the 'marked metaphor' of the locust serves to drive the point home. Both the audience whom the author wanted to encourage as well as the Assyrians whom he intended to mock was familiar with the nature and characteristic of locusts. These observed characteristics as sources in the metaphor (simile) were aptly applied to the target entities related to Nineveh and its strength base, its prominent officials.

Dietrich50 mentions that the Assyrians would have been familiar with the devastating effect of locusts and their characteristic behaviour of scraping the land clean and then flying away, not the least concerned with the devastation left behind. He argues that the Assyrians would not have been pleased by this comparison to the locust, to say the least. This certainly would have been a humiliating experience for the Assyrian city and its leadership, but the purpose of the oracle against Nineveh was to appeal to the people of Judah to place their trust in Yahweh's power. As sovereign power he would cause the downfall of Nineveh and the eventual demise of Assyria as an imperial power.

The 'marked metaphor' of locusts in Nahum 3:15-17 resembles destruction, but also desertion when loyalty was needed most. In terms of Nineveh and the Assyrian power structures, Nahum 3:15-17 depicts how a small insect such as a locust serves as a symbol of the demise of power centred in a remarkable city and the might of an imperial power. What it boils down to is that experience of nature (characteristics of locusts) has served as a vehicle for the prophet (poet) to speak in a creative way about the nature and demise of an abusive imperial power.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baker, David W. "Book of Nahum." Pages 560-63 in Dictionary of the Old Testament Prophets. Edited by Mark J. Boda and J. Gordon McConville. Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2012. [ Links ]

Basson, Alec. "'Rescue Me from the Young Lions': An Animal Metaphor in Psalm 35: 17." OTE 21/1 (2008):9-17. [ Links ]

Bosman, Jan P. Social Identity in Nahum: A Theological-Ethical Enquiry. 1. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Coggins, Richard J. and Han, Jin H. Six Minor Prophets through the Centuries. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [ Links ]

Coggins, Richard J. and Re'emi, Paul. Israel among the Nations: A Commentary of the Books of Nahum and Obadiah. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985. [ Links ]

Deist, Ferdinand E. and Vorster, Willem S. eds. Words from Afar. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1987. [ Links ]

Dietrich, Walter. Nahum Habakuk Zefanja. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2014. [ Links ]

Dobric, Nikola. "Theory of Names and Cognitive Linguistics - The Case of the Metaphor". Filozofja i društvo 21/1 (2010):31-41. [ Links ]

Dunn, James D.G. and Rogerson, John W. eds. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003, 687. [ Links ]

Floyd, Michael H. Minor Prophets. Part 2. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000. [ Links ]

Goldingay, John. "Nahum." Pages 5-43 in Minor Prophets II. Edited by John Goldingay and Pamela J. Scalise. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2009. [ Links ]

Han, Jin H. "Nahum." Pages 1-35 in Six Minor Prophets through the Centuries. Edited by Richard Coggins and Jin H. Han. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [ Links ]

Jindo, Job Y. Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered: A Cognitive Approach to Poetic Prophecy in Jeremiah 1-24. Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 2010. [ Links ]

Labahn, Antje. "Wild Animals and Chasing Shadows. Animal Metaphors in Lamentations as Indicators for Individual Threat." Pages 67-97 in Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible. Edited by Pierre Van Hecke. Leuven: Peeters, 2005. [ Links ]

Loader, James A. "Texts with a Wisdom Perspective." Pages 108-29 in Words from Afar. Edited by Ferdinand E Deist and Willem S. Vorster. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1986. [ Links ]

Mack, Russell. Neo-Assyrian Prophecy and the Hebrew Bible: Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2011. [ Links ]

Nogalski, James. Redactional Processes in the Book of the Twelve. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1993. O'Brien, Julia M. Nahum, Habakuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2004. [ Links ]

O'Brien, Julia M. Nahum. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 2002. [ Links ]

Robertson, O. Palmer. The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990. [ Links ]

Ryken, Leland, Wilhoit, Jim and Longman III, Tremper eds. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Spronk, Klaas. Nahum. Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1997. [ Links ]

Tate, W. Randolph. Biblical Interpretation: An Integrated Approach. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2011. [ Links ]

Tuell, Steven S. Reading Nahum-Malachi: A Literary and Theological Commentary. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2016. [ Links ]

Van Hecke, Pierre. ed. Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible. Leuven: Peeters, 2005. [ Links ]

Vermeulen, Karolien. "The Body of Nineveh: The Conceptual Image of the City in Nahum 2-3." Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 17/1 (2017):1-17, DOI:10.5508/jhs.2017.v17.al. [ Links ]

Wessels, Wilhelm. "Leadership in Times of Crisis: Nahum as Master of Language and Imagery." JSem 23/2i (2014):315-38. [ Links ]

Wessels, Wilhelm. "Nahum: An Uneasy Expression of Yahweh's Power." OTE 11/3 (1998):615-28. [ Links ]

1 Antje Labahn, "Wild Animals and Chasing Shadows. Animal Metaphors in Lamentations as Indicators for Individual Threat," in Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible, ed. Pierre Van Hecke (Leuven: Peeters, 2005), 68 uses the term 'marked metaphor' to refer to similes with the markers 'as' or 'like.'

2 This article is dedicated to Professor Hendrik Bosman. We commenced our academic careers together at the University of South Africa. He has always impressed me with his decency as a person and his academic competence. Although the book of Nahum is not the main focus of his research interest, he skillfully guided one of his students in writing a fine thesis on Nahum. Contact with Professor Bosman on both academic as well as personal level has always been an enriching experience, for which I am grateful. I wish him all the best in his future endeavours.

3 W. Randolph Tate, Biblical Interpretation: An Integrated Approach (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2011), 95.

4 James A. Loader, "Texts with a Wisdom Perspective." in Words from Afar, eds. Ferdinanad, E. Deist and Willem, S. Vorster (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1986), 117.

5 Job, Y. Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered: A Cognitive Approach to Poetic Prophecy in Jeremiah 1-24 (Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 2010), xv.

6 Wilhelm Wessels, "Nahum: An Uneasy Expression of Yahweh's Power," OTE 11/3 (1998):62.

7 Labahn, "Wild Animals," 68-71.

8 Labahn, "Wild Animals," 68.

9 Tate, Biblical Interpretation, 95.

10 Tate, Biblical Interpretation, 199.

11 Labahn, "Wild Animals," 68.

12 Labahn, "Wild Animals," 70.

13 Nikola Dobric, "Theory of Names and Cognitive Linguistics - The Case of the Metaphor," Filozofija i društvo 21/1 (2010):34.

14 Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered, 21.

15 Jindo, Biblical Metaphor Reconsidered, 21.

16 Cf. Alec Basson, "'Rescue Me from the Young Lions': An Animal Metaphor in Psalm 35:17." OTE 21/1 (2008):10-12.

17 Basson, "Rescue Me from the Young Lions," 11.

18 Wilhelm Wessels, "Leadership in Times if Crisis: Nahum as Master of Language and Imagery," J Sem 23/2i (2014):321-22. Steven S. Tuell, Reading Nahum-Malachi: A Literary and Theological Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2016), 11-12.

19 Klaas Spronk, Nahum (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1997), 138.

20 Jan P. Bosman, Social Identity in Nahum: A Theological-Ethical Enquiry (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2008), 168-69.

21 The precise meaning of this noun is uncertain and might be related to an Assyrian loanword.

22 This noun is probably and Assyrian loanword. It seems to be referring to an administrative person involved in military recruiting and therefore the translation 'scribe.' (cf. NET notes).

23 The suggested text-critical change by the BHS of the third person masculine singular suffix IHlpH to third person masculine plural suffix  is not accepted, since its antecedents

is not accepted, since its antecedents  and

and  ('a swarm of locusts') are in the singular; see also the third person masculine singular verb "

('a swarm of locusts') are in the singular; see also the third person masculine singular verb " (translated 'it flies away').

(translated 'it flies away').

24 James, D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson, eds. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 687.

25 Leland Ryken, Jim Wilhoit and Tremper Longman III, eds. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1998), 516.

26 Walter Dietrich, Nahum Habakuk Zefanja (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2014), 86.

27 Tuell, Reading Nahum-Malachi, 46. ; Thebes is known today as Karnack of Luxor and is about 530 km. south of Cairo.

28 Richard J. Coggins and Paul Re'emi, eds. Israel among the Nations: A Commentary of the Books of Nahum and Obadiah (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985), 53.

29 Cf. Michael H. Floyd, Minor Prophets. Part 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), 72.

30 Spronk, Nahum, 133.

31 An important discussion on the use of women metaphors in Nahum is offered by Julia M. O'Brien, Nahum (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 2002), 89-103. Cf. also Julia M. O'Brien, Nahum, Habakuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2004), 54-55.

32 Jin H. Han, "Nahum," in Six Minor Prophets through the Centuries, eds. Richard, J. Coggins and Jin H. Han (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 33.

33 Floyd, Minor Prophets, 75.

34 Coggins and Re'emi, Israel among the Nations, 55.

35 Han, "Nahum," 34.

36 James Nogalski, Redactional Processes in the Book of the Twelve (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1993), 124-27.

37 Cf. Dietrich, Nahum, 86.

38 Karoline Vermeulen, "The Body of Nineveh: The Conceptual Image of the City in Nahum 2-3." Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 17/1 (2017):12, DOI:10.5508/jhs.2017.v17.al.

39 Tuell, Reading Nahum-Malachi, 47.

40 Cf. O. Palmer Robertson, The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), 124-25.

41 Cf. Robertson, Nahum, 124.

42 It seems from the terminology used for locust in this verse that a new phase in the development of the locust is implied (Coggins and Re'emi, Israel among the Nations, 56).

43 Cf. John Goldingay, "Nahum," in Minor Prophets II, eds. John Goldingay, and Pamela J. Scalise (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2009), 42.

44 O'Brien, Nahum, 71.

45 Floyd, Minor Prophets, 75.

46 As already indicated, this word appears nowhere else in the Old Testament and therefore the exact meaning is not certain. Some scholars are of the opinion that it might be an Assyrian loanword with the meaning 'guard' (cf. Coggins and Re'emi, Israel among the Nations, 57).

47 Cf. David, W. Baker, "Book of Nahum," in Dictionary of the Old Testament Prophets, eds. Mark J. Boda, and J. Gordon McConville (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2012), 562.

48 Bosman, Social Identity in Nahum, 169.

49 Russell Mack, Neo-Assyrian Prophecy and the Hebrew Bible: Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2011), 214-15.

50 Dietrich, Nahum, 86-87.