Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.116 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/116-1-1199

ARTICLES

Singing the psalms: applying principles of African music to Bible translation

June Dickie

University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

Psalms were composed to be sung, and translated psalms should also be carefully constructed so that they are easily singable. This requires an understanding of the features of (indigenous) song and rhythm. Towards that end, this article seeks to summarise some important principles of African (particularly Zulu) music, and indicates some errors made in the past by translators of biblical material to be sung. Then some examples are given from a recent study which attempted to apply these principles to the translation of some biblical Psalms into isiZulu. The hope is that sensitivity to such musical features will facilitate a translation that communicates all the aesthetic beauty, rhetorical power, and memorability of the original.

Key words: Bible Translation; Music; Psalms; Rhythm; Isizulu

Introduction

The trajectories of music and Bible translation do not often cross, but there is a need for greater overlap, particularly in the translation of poetry. A fundamental feature of poetry is rhythm. Generally this consists of sound rhythm (created by assonance, alliteration, and rhyme) and poetic rhythm (arising from the form of the poetic line, structures such as parallelism, chiasm, and inclusio, as well as terseness). But if a poem is well-constructed, musical rhythm can also be applied fairly easily, converting it into a song. In order to do this, it is important for the Bible translator to understand the features of musical rhythm in the receptor culture. Also, he/she needs to understand the patterns associated with singing, to provide for these forms through a carefully-composed translation.

A recent study (Dickie, 2017)1 invited Zulu poets and musicians to participate in a workshop in which they were taught the basics of Bible translation, poetics, orality and performance. They then studied the Hebrew text of three psalms, made their own translations thereof, and performed them before an audience. Some interesting features emerged, but before these are addressed, attention will be given to aspects of biblical music to understand the role of the psalms in worship.

Biblical Music

Music and song have a powerful ability to move people emotionally, and thus have a distinct role to play in a person's worship. In the biblical cult, the psalms were composed to be sung (Mowinckel: 8), and to be sung in corporate liturgical worship at the Temple.2

Gunkel (1967) makes several interesting comments about music in the biblical cult. First (6-8), he argues that sung poetry was the best form to use for cultic sayings addressed by the entire community, as it allowed a large group to express itself in an orderly way, using a simple tune. Second, he suggests (37) that there was antiphonal singing, with an interweaving of "two distinct scores designed to be sung by dialoguing voices".3 Third, Gunkel posits that the performance of the psalms would have been accompanied by great emotion, to indicate the people's jubilation or lamentation. Music would have provided the rhythm and melody to allow them to lose themselves in the intoxication of their emotion.

Mowinckel (1962:9, 84, 89) maintains that the cult always used musical instruments to accompany the singing; these helped to maintain the meter. With the addition of accent signs to the Hebrew text, "musical inflection was provided for every word" (Waltke and O'Connor: 28). This facilitated the public cantillation of the Hebrew Scriptures. Along with the music and cultic song, there was cultic dance, which was a way to express delight in having an encounter with the holy (Mowinckel: 10-11).

Throughout history, music has interacted with other media to provide a rich experience of the biblical message (Soukup, 1997:221). J Ritter Werner4 calls for a return to such a unity of text, music, and gesture. African music traditionally shows such a unity, and thus an understanding of African music can facilitate a translation that better includes all the original functions of the Hebrew poetic text.

African (particularly Zulu) Music

There are many commonalities in the music across Africa (Jones, 1959:200; Nketia, 1974:241). First, a characteristic of most African music is that it is integrated in the ordinary life of the people (Axelsson, 1971:1); songs are sung in most contexts.5 One reason why music is so central to community life in Africa is that it is often the means of communicating important messages, thereby suggesting the potential to use it to spread the biblical message too.6

Music is one of the major forms of oral art in African societies, and is always performed before an audience. Thus the dynamics of performance criticism and reception theory come into play.7 One of these is that the context will vary for each performance, and thus the audience will find each presentation of a piece of music lively and fresh, no matter how many times they might have heard it before. The music becomes integrated into the social situation, and each new set of circumstances allows the artist to be creative in a different way (Chernoff, 1979:61).

African musicians are alert to the social situation and the response of the audience, and will change or extend their lyrics or rhythms to fit the changing situation (Chernoff: 66). For example, in the empirical study which forms the basis of this article,8 two Zulu poets performing rap responded to the warmth of the audience by linking their arms as they recited the chorus line "We all together, we lift God" thereby using gesture to affirm the meaning. This did not happen the first time they performed the item, but as the audience became familiar with the words and engaged more with the performance, the performers responded accordingly. In another performance, a Zulu singer extended the lyrics of her song as the audience responded with appreciative snapping of fingers.9

Audience involvement is a key part of any oral performance, and interjections and participation from the audience are expected by the performer (Swartz, 1956:29-31). The lack of visible response is a negative evaluation, and the performer may simply stop if s/he is not affirmed (Cope, 1968:30). The audience also expects to be able to participate. As Lury (1956:34) notes: "The African's musical sense is inside him... He is a performer rather than a listener." As a result, an African audience cannot remain silent or immobile during the performance of oral art. The rhythm, if not the words, must be expressed.

Another common feature is repetition - both of lyrics and rhythms. Repetition serves many functions. Here it is noted that repetition of a drumming style is a way of maintaining the tension of the beat, in order to get the maximum effect when the style is changed (Chernoff, 1979:113). For example, in the empirical study, a performance10 of Psalm 93 had nearly two minutes of drumming and the singing of a simple chorus "hey mama, hey papa" preceding the rap version of the psalm. The initial establishing of a strong rhythm, and then the change of style when the main message began with the speaking, was highly effective. The audience was drawn into the rhythm, and their attention was held through the change in form to the spoken message.

John Chernoff (1979:112) emphasises the importance of repetition in African music: it is not perceived as redundant, but forms part of the whole unit. Focus on the whole is typical of African music in many ways. Turino (2004:177-8) notes that "a piece of music" must be conceived of as a totality of musical resources, connected and improvised in various ways, resulting in the unique performance of each piece.

The various performers are very aware of one another and of their united creative expression, rather than of themselves as individuals taking the limelight (Chernoff: 113). For example, a Zulu performance of Psalm 9311 began with five men and nine women singing a chorus, followed by the nine women (without the men) repeating the same line. After several repetitions of this pattern, a drummer came to the fore and the others hummed. This was followed by the performance of the first rapper and of a second rapper, and finally the whole group sang the chorus again to complete the item.

Another common feature in African music is dependence on short units of lyric. Bruno Nettl (1965:124) claims that this is the most striking thing about African music. The short lines are repeated, or alternated, or combined, to form a longer unit. For example, a Zulu sung performance12 of some verses from Psalm 145 shows one chorus-line of three words repeated 12 times interchanging with another of two words repeated six times.

There are many other common characteristics of African music, including the functions it achieves. An important function of music, particularly in predominantly-oral societies, is its collective and communal power (Sacks, 2007:244, 247). A community clapping or moving in synchrony is bound together by the rhythm, which everyone present internalises. Listening becomes active and motoric, as the rhythm synchronises the brains of all who participate. An additional benefit of music is to allow people to organise and hold a large amount of information in the mind.13 Music has the power to embed sequences in a melody (Sacks: 237).14 The melody is recalled in the same way that one walks - one step leading to the next. In an oral society, this mnemonic function of music is very important.

Throughout the centuries, music in African society has been linked to religious practice. For example, in Shona society, the most typical role of music is in the rituals of traditional religion (Axelsson, 1971:8). Music is used to enhance the religious sensitivities of the participants in the ritual. Often the rhythm chosen distinguishes between music used for religious purposes, and that used for other purposes (Tracey, 1965:11). Even today music is an integral part of different African religious groups. The Shembe church (popular among some segments of Zulu society) has incorporated traditional patterns of music in their worship, and thereby claims that one can convert to Christianity without losing one's cultural ways (Muller, 1994). For example, they use call-and-response singing and rhythm as "the driving musical parameter" (Muller, 2003:107).

Thus it is helpful to consider next a brief review of the way in which music has been used in the religious domain from the missionary era until today. Attention is specifically focused on errors made in the past and possibilities for the present.

History of Christian Music in Africa

Olof Axelsson (1971) delineates three stages in the history of Christian music in southern Africa: first, European music was adapted; second, there was a fusion with foreign influences; and third, new church music emerged using traditional elements of African music. Thus the early years illustrate methods to be avoided, whereas the later years indicate exemplary elements, of help to the modern translator.

Mistakes made: Initially indigenous music was not encouraged by the missionaries as they feared it would draw converts back into their 'sinful past' (Axelsson: 46). Western hymns were translated into the African languages, and were sung to Western melodies. This resulted in two problems (Jones, 1949:9): first, the tonal patterns of the indigenous language never fit the European tunes; for example, the tone was rising when the tune was falling. Second, the indigenous language usually did not comply with the meter of the Western melody.

Moreover, the mission texts were rarely understood by local people, and often took on meanings never intended by the translators (especially because of the tonal dimension in many African languages).15 There are many examples of "crude rhyme schemes" which resulted in texts of a very poor standard (Muller, 2003:104).16

Also, during the early years, little attempt was made to utilise the form of indigenous music. Missionaries did not consider praise poems (very popular among many African groups) as worthy of being imitated, although they did utilise the form of some lyrical songs.17 Church music was usually rhythm-less (Dargie, 1991 a great problem as "African music cannot be experienced without movement" (Dargie, 1983:38).

Positive elements: During the years of 'fusion music', Zulu traditional idiom became fused with various imported styles to produce urban black popular music. One form that developed at that time was isicathamiya, often using lyrics that were metaphorical and religious. Another was kwela (Ballantine, 1993:8, 34), using tunes based on familiar African Christian hymns. Zulu composers showed an ability to fuse traditional forms (particularly cyclical rhythm patterns) with imported ideas. As Mthethwa (1988b:34) notes: "This gives them a new lease of life."

From the 1950s, Western ethnomusicologists (e.g. Weman, 1957)18 sought to introduce church music based on African traditional music. Antiphonal and responsive singing was used to sing psalms, and tunes were based on indigenous songs. These followed the natural downdrift typical of African songs and thus were highly singable; the melodies were short and easily learned (Axelsson: 65). Moreover, Weman (1960:73) tried to adhere to the pattern of the spoken language, and the result was well received. He tried to encourage African musicians to compose songs and to follow the tonal pattern of the language and the rhythmic pattern of traditional music.

Indeed, by the 1960s, African composers across Africa were being encouraged to compose new music following an African idiom (Axelsson, 1971:60-61). This was particularly successful in the rural areas with non-literate composers creating indigenous music, often accompanied by traditional instruments (e.g. rattles and drums). Sometimes, if the music was played outside the church building, dance was also part of the event. In the Catholic Church, local composers were encouraged to use indigenous forms (including rhythm). One of the most famous examples was the Missa Luba, utilising features of traditional Congolese folk-music, resulting in "a rather ingenious rhythmic, harmonic, and polyphonic texture" (Axelsson, s.a.: 94).

In the development of traditional African music, the older generation of song-writers were Bantu missionaries who wrote sacred songs,19 while the new generation of Bantu song-writers tried to break away from sacred songs. Nevertheless, current 'sacred song' needs a new infusion of Africanisation, which could come about if translators become sensitive to the characteristics which make music ' African'. In the next section, certain characteristics of Zulu vocal music are discussed, with examples from the recent empirical study.

Vocal Music

Vocal music is very important among the Zulu community, and in much of Africa. As Kodaly notes, "The instrument most accessible to everyone is the human voice" (Szonyi: 13). Axelsson (1971:vi) observes that "African music is first and foremost vocal in style." Nketia (1974:244) explains that vocal music is emphasised in African music because singing provides the greatest opportunity for people to participate in group events.20 It is also thought that the Nguni people (including the Zulus) use instruments to a lesser degree than West Africans partly because of the lack of trees for wood (Tracey, 1963:36). However, the Nguni people formerly all used musical bows21 (Rycroft, 1967:90) but this was for individual performance. Communal music seems to have been exclusively vocal, apart from the use of ankle-rattles in dance-songs. However, rhythm is an integral part of their music, and thus the Zulus may use clapping or foot-stomping to externalise the meter, and at times, rattles, drums, or gongs may also be used. Such devices facilitate repetition of the words, and help with memorisation.

Features of Zulu vocal music are now presented with some empirical examples.

• Voice-parts

Most researchers seem to agree about the structure of Zulu songs. The simplest form is responsorial, with a song-leader initiating and maintaining the song (Swartz, 1956:29-31), and a chorus echoing the material. Another common form is antiphonal singing, in which the two parts22 sing non-identical texts, and begin at different times (Rycroft, 1967).23 It is accepted by most that the song begins with the chorus,24 and the melody sung by the chorus identifies the song.25 The lyrics of the chorus tend to remain unchanged throughout a song, but the soloist may improvise with the words. Also, the start and end points of the solo part may change at times.26

In both responsorial and antiphonal singing, the chorus may, or may not, overlap with the soloist. The former is more common, with the amount of overlap varying (Rycroft, 1967:93). The two parts may be repeated multiple times, with the soloist introducing slight variations in the melody. However, as noted above, the melody and text of the chorus remains the same. The overlapping of some phrases of the soloist and the chorus produces a form of 'harmony'. Erich Hornbostel calls this overlapping 'polyphony', which may lead to the singing of two melodies together (Merriam, 1982:87).27 In such singing, the length of the melodic structure is usually short.

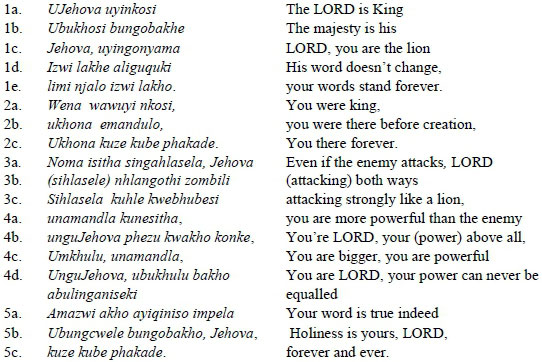

An example of a Zulu song based on Psalm 9328 illustrates many of these facets. The psalm as translated by a group of five Zulu youth is shown below:

The performed song consisted of all the cola from the translation with the exception of the final colon, 5c but with the order of the cola changed slightly. First the whole group sang cola 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d twice, and then followed it with cola 2a, 2b, 2c, and 1e sung twice. Both of these sections were sung with a steady rhythm and some harmony, but all sang the same words at the same time. Then one of the ladies began singing a stirring solo, while the group continued to sing a chorus of cola 4b, 4c, and 4d twice. The words of the soloist were not clear, although the word 'Jehova' leapt above the chorus, in an emotive, heart-wrenching way.29 This was followed by a second soloist singing alone cola 3a, 3b, 3c, and 4a twice and then cola 5a, 5b. The group then sang 4b, 4c and 4d twice while the first soloist sang her own part again, piercing effortlessly above the chorus.

In this performance, some of the principles mentioned above are apparent. Firstly, the song clearly followed the antiphonal form, beginning with a stable chorus, followed by a soloist singing a different melody and different lyrics to the group. The chorus was repeated without change, but the (first) soloist showed some variation in the melody as she repeated it later in the song. Moreover, her role seems to have been (as suggested by Rycroft30) to add colour to the performance, rather than to convey the main message.

' Polyphony' was apparent with overlapping of the (first) soloist voice with that of the chorus. Two melodies were sung together, although the soloist ended before the group. As the literature shows, the length of the cola was short (4 beats to a colon). In the second soloist part, there was no overlap with the chorus.

In this study (Dickie, 2017), in which 19 songs were performed by Zulu artists, none of them used responsorial singing, but most used antiphonal singing.

• Timbre

The timbre of the voice plays an important role. The soloist usually sings on a level one tone higher than the chorus (Rycroft, 1967:90). The lower pitch of the chorus provides a pleasing balance. This was found to be the case in the empirical study:31 the (first) soloist soared above the chorus, and the second soloist (also a woman) sang with a high pitch, causing the chorus (which included two male voices) to be perceived as a pleasing counterpoint.

Women also tend to ululate; the prolonged, high-pitched, penetrating cadence is understood by the Zulu people as a sign of excessive joy and great respect. The audience in the empirical study used ululation as a positive endorsement.

The end of the song is not signalled by a 'collective cadence' as often happens in Western music. This is because of the circular form of the music and the lack of finality (Rycroft, 1967:103). Rather the song is repeated any number of times, until the leader deems the time right to terminate and chooses to bring it to an end. For example, in a performance of Psalm 93,32 a chorus was sung consisting of groups of cola sung at various times. The song-leader then picked up a drum and as he tapped it gently, the whole group reverted to humming the same tune. This served as transition for two rappers, who performed one after the other, after which the soft drumming and humming continued. Thereafter, the youth-leader directed the group to sing, and they began enthusiastically with the first colon of the chorus. However, at the start of the second colon, he spoke to the song-leader, and the whole group took his lead and faded out, with a sudden and unexpected conclusion to the item.

• Harmony

Many of the early ethnomusicologists (e.g. Axelsson) assert that traditional African music does not contain the Western idea of four-part harmony. Some (e.g. Swartz, 1956:29-31) contend that harmony has been replaced by call-and-response. Others (e.g. Jones, 1949:2) believe that rhythm has taken the place of harmony. This is disputed by African researchers, Bongani Mthethwa (1988:31) and Caesar Ndlovu (1989:45), who maintain that harmony is an integral part of indigenous African music. Mthethwa claims that both African and European music have harmony, melody and rhythm, but Europeans focus on harmony whereas Africans focus on rhythm. Ndlovu cites isicathamiya as an example of choral singing which has four voice-parts: usually there are 8-20 voices, the leading one a tenor, then a soprano, one alto, and the remainder bass voices. The empirical examples indicate a sonorous harmony in most songs.33 The presence of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass voices in the chorus seemed to depend on the availability of persons able to lead such parts.

• Melody and Speech

African music is derived from language (Chernoff, 1979:75), thus, both rhythms and melodies are constrained by the dimensions of language. Moreover, most African languages are tonal (Greenberg, 1966). Consequently an African composer will find it difficult to write a rising melody when the words have a falling intonation (Chernoff, 1979:80). However, early Western musicologists disputed the importance of this factor. Hornbostel (1928:31-32) writes: "The pitches of the speaking voice ... have no influence upon (the melody)." Herzog (1934:466) also notes: "A slavish following of speech-melody by musical-melody is not implied." However, Jones (1949:11-12) maintains that the tune "does all along conform to the speech line", and thus each verse of a song differs slightly in melody. Nettl (1965:123) shows that, although the tones of the words do influence the shaping of the melody, each culture may evolve its own relationship between language and music.

It is agreed that normal speech (i.e. not questions) usually shows a downward drift, and thus African melodies tend to show the same movement, which Jones (1949:11) describes as "like a succession of the teeth of a rip-saw ... The tendency is for the tune to start high and gradually to work downwards in this saw-like manner."

Concerning the relationship between speech tone and melody, the observation by John Carrington (1948:198-99) is notable. He suggested that in writing African songs, "We begin with the words, and then from the tonal patterns of these words, the music emerges." Whether or not the emerging melody will follow the tonal pattern exactly will depend on the intuitive sense of the musician. This is the approach that was followed in the empirical study: the translation was first completed, and then the musicians read the text aloud and hummed the tonal melody, until a musical melody emerged.34

• Relationship of Words to Notes

In Zulu songs (and most African songs), the words and the tune are inseparable (Jones, 1959). The accentuation of the words must be correct, and this requires that the stressed syllables match the beat of the tune. It was noted in the empirical study that musicians would sometimes change the word order or delete an unnecessary word to ensure that the accent of the words fall on the beat. For example, in the song below (based on Psalm 145:1),35 the performers omitted the shaded words; the meaning was not significantly altered, and the correct stress and rhythm were achieved.

1a. Ngizokuphakamisela igama lakho phezulu, Jehova, oh Nkosi.

I will lift high name your above, LORD oh King,

1b. Ngizolidumisa igama lakho njalo-njalo.

I will praise name your continually.

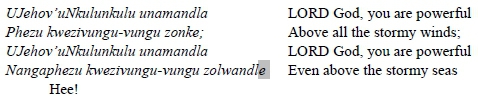

Just as one may need to delete words that upset the rhythm and accentual system of the language, so too it may be necessary to add syllables. This may be done through repetition, the inclusion of nonsense syllables (Rycroft 1967:94), prolonging a final vowel (Nketia, 1974:179) or adding an interjection at the end of a chorus (Swartz, 1956:29-31).36 For example, in the performance of the chorus below,37 the final vowel (shaded) was significantly prolonged; however on the final repetition of the chorus, the nonsense syllable ' Hee!' was added instead.

• Lyrics and Melody

The early practice of the missionaries was simply to translate European hymns and sing these words to the European melody. But Jones (1964:6) insists that the words and tune should be generated simultaneously "as a single indivisible unit". Tracey (1967:50) agrees; one needs "a new indigenous form free of mundane associations". Indeed, importing a folk-tune and applying new words can be hazardous. However, in the empirical study, one performer successfully used a hymn tune to sing his new translation,38 but it should be noted that he had to extend many syllables to fit the melody, which perhaps indicated a "not particularly good fit". Another group39 used a recorded rhythmic beat to accompany their song and rap item. However, this did not constrain the lyrics in any way, but assisted the group to maintain a good rhythm, and for the rapper to keep his performance within the same beat.

The attributes of African (and particularly Zulu) vocal music have been considered. The next big theme in Zulu music is that of rhythm.

Zulu Notions of Rhythm

It is generally agreed that the most significant feature of African music is its rhythm (Axelsson, 1971:19). Chernoff (1979:23) maintains that rhythm is "the most perceptible" but "least material thing". Ronald Rassner (1990:244) concurs, stating that "An audience feels a performance through rhythm." However, it is also noted that "rhythm is probably one of the most profound yet misunderstood aspects of music making in Africa" (Kaufmann, 1980:393).

For the purposes of this article, only a few significant attributes will be discussed, with some application within the empirical study. First, as Merriam (1965:65) adduces: "African music depends on percussive effect." For the Zulu, this may be provided by drums or other instruments (including the hands and feet) or in some other way, such as by "shaking a tin filled with small stones" (Ballantine, 1993:35). African music always has "invariable and repeated rhythmic patterns" (Axelsson, s.a.: 97), whether they be aurally heard or internally comprehended by the musician and audience.

Dargie (1991:ix) observes that "the Zionist independent indigenous Christian churches have long led the way in rhythmic church music". Often the rhythm dominates,40 even at the expense of the words. In this study, the text had to be in focus as the words are an essential element of the translation. However, some performances showed an exciting use of rhythm. For example, one version of Psalm 93 began with two minutes of drumming and the singing of a simple line calling the audience to listen. This served to establish a strong rhythm, and draw in the audience (they joined in with the humming) before the main message was delivered through rap. The change of form from the drum-and-hum to the rap was an effective attention-getter.

Rhythmic patterns used in Africa are complex (Chernoff, 1979:40), certainly to the Western ear. This is because there are often multiple rhythms being played simultaneously; the stress is on different beats; and rhythm dominates harmony and melody. These features will be discussed briefly.

Multiple Rhythms: It has been claimed that African music always has at least two rhythms,41 with no obvious main beat,42 and the rhythms seem to compete for attention. Curt Sachs (1953:40) maintains that there is nevertheless "agreement on a higher artistic level of disagreeing rhythms." Jones (1964:27) agrees, noting that "It is in the complex interweaving of contrasting rhythmic patterns that (the African) finds his greatest aesthetic satisfaction."

Stress Patterns: Rhythm in Western music results from the melody. It is counted evenly, and the stress is on the main beat (Chernoff, 1979:41). Alan Merriam (1982) explains further that in Western quadruple metre music, the notes fall on the first and third beats, whereas in African music, they fall on the second and fourth beats.43 Thus the meter in African music sounds ' off-beat' to the Western ear.

Dominance of Rhythm: In Western music, harmony and melody take prominence over rhythm; the tones in Western music are sounded simultaneously to produce harmony, or successively to produce melody (Chernoff: 40-42). However, African sensibility is very different; the melody is clear, and the tones apparent, but it is the rhythm which dominates.

• Meter

Zulu music does seem to show a steady time pulse, a 'regulative beat' (Nketia, 1963:64) or meter. Waterman44 asserts that this underlying beat may be sounded out, imagined in the mind, or expressed through physical movement (e.g. through dance). Chernoff (1979:49) also maintains that "an additional rhythm" (or meter) must be discerned if a person is to be able to establish stability in the midst of multiple rhythms, and thus to interpret African music.

In the empirical study, rhythm (playing off an underlying meter) was apparent in all the performances, both those sung and spoken. This was largely because the composers had paid attention to the poetic line, looking for consistency in the number of stressed syllables per line. Towards this end, they sought to use terse language, which was metonymic and metaphoric.45 For example, in a sung version of Psalm 145,46 each line had eight beats (with the vowels in some words extended), to give a regular meter.

In the same study it was noted that six of the thirteen songs had an ' internal meter' (i.e. not sounded out), derived simply from the poetic line. However, other performers sounded out the meter, through the use of drums. Rhythm patterns were established through the swaying of the body, dancing of the feet (taking a step to the left and then back to the right), nodding of the head, restrained clapping, or snapping of fingers. One group47 swayed their legs and snapped their fingers as they sang, with a recorded drum beat giving the basic meter but their snapping and their swaying following different rhythms, playing off this regular pulse.48

Corporate Performance

In Zulu music, timing is relative to the other performers. Each musician depends on the others for her/his timing of the rhythm, and for perceiving when to enter the ensemble (Chernoff, 1979). This was apparent in the group performances in the empirical study, particularly when a soloist was to follow a group chorus.49 The performance is seen as a corporate endeavour, and musicians see their role within that of the larger ensemble and community.

Incorporation of African Rhythm in Translation of Biblical Psalms

For a Western Bible-translator, the application of the theory of African rhythm to the translation of poetry can appear daunting. Even specialist ethnomusicologists from the West battle to analyse exactly the issues involved. However, perhaps an understanding of the technical details is not necessary. As David Dargie (1983:259), an accomplished ethno-musicologist, concludes: "(African) music is something living, growing out of a vital, vivid style. To trammel it up with technique is all wrong... "

African musicians have within them the capacity to convert a well-formed poem into a song. The translator needs to focus on the sound and poetic rhythm, and allow the musician freedom to apply the musical rhythm. This is in line with the words of Donatus Nwoga (1976:26) that: "The characteristic mode of African aesthetic perception is non-analytical . but rapport with the art."

• Examples of sung Scripture (using traditional Forms)

Over the centuries various translators and musicians have sought to sing or chant Scripture. Luther provided musical adaptations to allow for the chanting of the German Bible. Although they were musically sensitive, they had minimal impact, but this tradition did provide the liturgical setting for Bach's great Passions (Werner, 1999:180).

Certain portions of Scripture seem to lend themselves more easily to being sung, either as a result of their poetic form, their liturgical function (e.g. the Lord's Prayer), or their brevity (e.g. Psalm 134). Werner (1999:195) studied three musical versions of the Lord's Prayer (dating from the fourth to the sixteenth centuries) and found that all were "accurate and faithful, in ways that silent linguistic translation is not".

Another Bible translator who has experimented with musical versions is Herbert Klem (1982:xx), working in Nigeria. He had six chapters of the book of Hebrews set to traditional Yoruba music, and found that the use of music greatly increased the enjoyment and interest in learning the text, and that the material was retained much better. Actually, Klem (1982:178) found that using both written materials and songs was the most effective way to teach new biblical material. However, if only one medium was used, song was found to be more effective than just written materials. Even literate young people enjoyed learning to sing the songs from memory.50 And using an oral learning style closed the social distance between those who were literate and those who were not.51

Nkrumah (2012:17) also cites a case in Ghana where Scripture songs in the mother tongue used the traditional music styles of the people. The advantages are many, including enhanced memorisation as well as attracting those not otherwise interested in Scripture. The recent empirical study among young Zulus52 has shown that many advantages accrue by seeking to translate biblical Psalms in a musically-sensitive way. The audience53 enjoyed the performances, recognised the text as Scripture, and found the words (especially the repeated chorus parts) easy to remember.

Before closing, perhaps a brief comment is in order concerning the 'accuracy' to the source text of the translations in the empirical study.54 The traditional criteria used for evaluating a print translation (accuracy, naturalness and clarity) are not necessarily the most appropriate in a performance-based translation, where authorisation is largely in the hands of the receiving community (as per reception theory).55 The advantages of accessibility (being oral/aural) and acceptability (being in the form of traditional praise poetry/music) are significant.

As we consider the possibilities of incorporating other media in Bible translation, it is well to remember the words of Rowe (1999:63): 'We are the translators and communicators not of God's book, but of God's Word.' His Word can go out in many innovative ways, including through the form of sung Scripture. For many communities, especially in Africa, this is a powerful resource waiting to be utilised.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amzallag, N 2014. 'The Musical Mode of Writing of the Psalms and its Significance", OTE 27/1:17-40. [ Links ]

Axelsson, O s.a. "Historical Notes on Neo-African Church Music. Publication of Kwangoma College of Music, Bulawayo": 89-102 [ Links ]

Axelsson, O 1971. African Music and European Christian Mission. Sweden: Uppsala University. [ Links ]

Ballantine, CJ 2012. Marabi Nights: Jazz, 'Race' and Society in early Apartheid South Africa. Pietermaritburg, South Africa: UKZN Press. [ Links ]

Brown, D 1998. Voicing the text, South African oral poetry and performance. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Carrington, J 1948. "African Music in Christian worship", Int. Review of Missions 37:198-205. [ Links ]

Chernoff, JM 1979. African Rhythm and African Sensibility. Chicago: University of Chicago. [ Links ]

Cope, AT (ed.) 1968. Izibongo Zulu Praise Poems. London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dargie, D 1983. "Workshops for Composing Local Church Music", No. 40 of the series Training for Community Ministries. Lady Frere, South Africa: Lumko Missiological Institute. [ Links ]

Dargie, D 1991. Lumko Hymnbook. African Hymns for the Eucharist. Delmenville: Lumko. [ Links ]

Dickie, JF 2017. "Zulu Song, Oral Art, Performing the Psalms to Stir the Heart." PhD Thesis. UKZN (Pmb). https://www.academia.edu/31091578/ZULU_SONG_ORAL_ART_PERFORMING_THE_PSALMS_TO_STIR_THE_HEART_Applying_indigenous_form_to_the_translation_and_performance_of_some_praise_psalms [ Links ]

Finnegan, R 1988. Orality and Literacy. Oxford: Basic Blackwell. [ Links ]

Finnegan, R 2012: Oral Literature in Africa. Cambridge: Open Book Publication. [ Links ]

Gluck, JJ 1971. "Assonance in Ancient Hebrew Poetry: Sound Patterns as a Literary Device" in IH Eybers et al. (eds.). De Fructu Oris Sui. Essays in Honor of Adrianus van Selms. Leiden: Brill: 69-84. [ Links ]

Gunkel, H 1967. The Psalms. A Form-Critical Introduction. Philadelphia: Fortress. [ Links ]

Herzog, G 1934. "Speech-melody and Primitive Music". Musical Quarterly, 20:452-66. [ Links ]

Iser, W 1974. The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Jones, AM 1949. "African Music in Northern Rhodesia and some other Places". Occasional Paper of the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum, No. 4. Livingstone. [ Links ]

Jones, AM 1959 (1961). Studies in African Music, Vol. 1 (text). London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Jones, AM 1964. "African Metrical Lyrics". Journal of African Music, Vol. 3, 3:6-14. [ Links ]

Kaufmann, R 1980. "African Rhythm: a Reassessment". Ethnomusicology 24:3. [ Links ]

Kirby, PR 1926. "Old time chants of the Mpumuza Chiefs". Bantu Studies, Vol. 1:23-24. [ Links ]

Klem, HV 1982. Oral Communication of the Scripture. Insights from Oral Art. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library. [ Links ]

Kodaly, Z 1967. "Folk-Song in Pedagogy". Music Educators' Journal, March 1967, Vol. 53, No. 7:59. [ Links ]

Locke, T 2009. "Orff and the 'Ivory Tower': Fostering Critique as a Mode of Legitimation". International Journal of Music Education, Vol. 27, 4:314-325. [ Links ]

Longman, T III and Enns, P 2008. Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry, and Writings. Nottingham, England: IVP. [ Links ]

Lury, EE Rev Canon, 1956. "Music in African Churches", Journal of African Music, 1, 3:34-36. [ Links ]

Merriam, AP 1965. "The Importance of Song in the Flathead Indian Vision Quest". Ethnomusicology, Vol. 9, No. 2:91-99. [ Links ]

Merriam, AP 1982. African Music in Perspective. New York: Garland. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, S 1962, 1982. The Psalms in Israel's Worship. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Mthethwa, B 1988. "Syncretism in Church Music: Adaptation of Western Hymns for African use". Paper presented at 7th Symposium on Ethnomusicology. International Library of African Music: 32-34. [ Links ]

Muller, CA 1994. "Nazarite Song, Dance and Dreams: The Sacralisation of Time, Space and the Female Body in South Africa" (thesis). New York: NY University Press. [ Links ]

Muller, CA 2003. "Making the Book, Performing the Words of Izihlabelelo zama-Nazaretha", in JA Draper (ed.) Orality, Literacy and Colonialism in Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: SBL (Cluster Publication: 91-110. [ Links ]

Muller, CA (ed.) and Mthethwa, B (translation) 2010. Shembe, Isaiah and Galilee. Shembe Hymns. UKZN. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, C 1989-1990. "Scathamiya: A Zulu Male Vocal Tradition". Papers presented at the 8th and 9th symposiums of Ethnomusicology. International Library of African Music: 45-48. [ Links ]

Nettl, B 1965. Folk and Traditional Music of the Western Continents. NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Nketia, JHK 1963. African Music in Ghana. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Nketia, JHK 1974. The Music of Africa. New York: WW Norton. [ Links ]

Nkrumah, N 2012. "The Impact of Bible Translation: A Case Study of the Okuoku Cult". Journal for African Christian Thought 15, 2:15-19. [ Links ]

Nwoga, D 1976. "The Limitations of Universal Critical Criteria" in R Smith (ed.) Exile and Tradition: Studies in African and Caribbean Literature. New York: Africana Publication Company: 8-30. [ Links ]

Rassner, RM 1990. "Narrative Rhythms in A Giryama Ngano: Oral Patterns and Musical Structures" in I Okpewho (ed.) Oral Performance in Africa. Nigeria: Spectrum: 228247. [ Links ]

Rowe, GR 1999. "Fidelity and Access: Reclaiming the Bible with Personal Media" in PA Soukup and R Hodgson (ed.). Fidelity and Translation. Communicating the Bible in New Media. New York: American Bible Society: 47-63. [ Links ]

Rycroft, DK 1967. "Nguni vocal Polyphony". Journal of International Folk Music, XIX:90-103. [ Links ]

Sachs, C 1953. Rhythm and Tempo. A Study in Music History. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Sacks, O 2007. Musicophilia - Tales of Music and the Brain. Britain: Picador. [ Links ]

Soukup, PA 1997. "Understanding Audience Understanding" in PA Soukup and R Hodgson (ed.). From one Medium to Another: Communicating the Bible through Multimedia. Kansas City, MO: Sheed and Ward: 91-107. [ Links ]

Swartz, JFA 1956. "A Hobbyist looks at Zulu and Xhosa Songs". Journal of African Music, Vol. 1, 3:29-33. [ Links ]

Szonyi, E 1973. Kodaly'sPrinciples in Practice. London: Boosey and Hawkes. [ Links ]

Tracey, A 1963. "The Development of Music". Journal of African Music, Vol. 3, 2:36-40. [ Links ]

Tracey, H 1967. "Musical Appreciation in Central and Southern Africa". Journal of African Music, 4/1:47-53. [ Links ]

Turino, T 2004. "The Music of Sub-Saharan Africa" in B Nettl. Excursions in World Music. New Jersey: Pearson: 171-200. [ Links ]

Vilakazi, BW 1993. "The Conception and Development of Poetry in Zulu", in R Kaschula (ed.). Foundations in Southern African Oral Literature. Wits University Press: 55-84. [ Links ]

Von Hornbostel, Erich M 1928. "African Negro Music". Africa 1:30-62. [ Links ]

Waltke, E and O'Connor, M 1990. An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. Winona R Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Weman, H 1960. African Music and the Church in Africa. Studia Missionalia Upsaliensia, 3, Svenska Institutet for Missionsforskning, Uppsala. [ Links ]

Werner, JR 1997. "Musical Mimesis for Modern Media" in PA Soukup and R Hodgson (eds.) From one Medium to Another: Communicating the Bible through Multimedia. Kansas City, MO: Sheed and Ward: 221-227. [ Links ]

Werner, JR 1999. "Midrash: A Model for Fidelity in New Media Translation" in PA Soukup and R Hodgson (ed.). Fidelity and Translation. Communicating the Bible in New Media. New York: American Bible Society: 173-197. [ Links ]

1 https://www.academia.edu/31091578/ZULU_SONG_ORAL_ART_PERFORMING_THE_PSALMS_TO_STIR_THE_HEART_Applying_indigenous_form_to_the_translation_and_performance_of_some_praise_psalms

2 Longman and Enns: 485.

3 See also Amzallag, 2014:29-35.

4 Cited by Soukup, 1997:225.

5 Osadebay, cited by Finnegan, 2012:236.

6 For example, the Mozambican government used song and drama to spread the message of AIDS (personal experience, 2004).

7 For example, see the work of Foley (1995) and Rhoads (2012).

8 See Song 52, Dickie, 2017:332.

9 Item 32, Dickie (2017:320).

10 Item 5, Dickie (2017:275).

11 See Item 7, Dickie (2017:279).

12 See Item 9, Dickie (2017:314).

13 Sacks (2007:237) claims that the most powerful mnemonic devices are rhyme, meter and song.

14 For example, the composer Ernst Toch was able to remember a very long string of numbers after a single hearing by converting them into a tune, corresponding to the numbers (Sacks: 237).

15 Axelsson, s.a.: 92-3.

16 Rhyme is not usual in Zulu poetry. It may occur, but this is more incidental (based on the concordance system) than intentional. See Muller, 2003:104.

17 Vilakazi (1993:74-77).

18 CSM Mission Board Minutes 569 31/10, 1957.

19 An example is Enoch Sontonga, who created the hymn Nkosi Sikelela iAfrika, which has become the national anthem of South Africa (Swartz, 1956:31).

20 Kodaly teaches that choral singing contributes to a child's sense of community and the need to work with others (Szonyi: 41-2).

21 The Zulu musical bow is still used to a limited extent: Brother Clement of the Catholic mission in Vryheid continues to encourage school-children to learn to make bows, and play them.

22 Nketia (1974:142ff) notes that Zulu choral singing may include a third part, either dependent or not on one of the other parts. The music educationist, Kodaly, believes that two or multi-part singing is essential to develop musicality in people (Szonyi: 38).

23 Another kind of song, common in Zionist churches, arises spontaneously. A leader may use a song to bridge a gap in the flow of speech, or to halt it (Kiernan, 1991:392).

24 Kirby (1926); Rycroft (1967:91, 95).

25 Chernoff (1979:56) also highlights the prominence of the chorus relative to the soloist.

26 Rycroft (1967:91, 95) posits that, given the relative completeness of the chorus lines, the soloist part may have been an addition, improvised to add colour.

27 Nettl (1965:133) claims that African music also possesses rounds, which often seem to have come about through antiphonal or responsorial singing. Most known African rounds have only two voices.

28 See Item 6, Dickie (2017) for the video version.

29 Rhetorically, the soaring solo served the purpose of drawing the audience in, to pay attention to the chorus. The actual words of the first soloist were not in focus, but rather the rhetorical power of the melody.

30 See footnote 18 of this article.

31 Item 6, Dickie (2017:277).

32 Item 7, Dickie (2017:279).

33 For example, Dickie (2017:279) (Item 7) and Dickie (2017:314) (Item 9).

34 The music educationist Kodaly notes that melodies should be introduced by singing them first, not by playing them on the keyboard (Szonyi: 13).

35 Item 9, Dickie (2017:314).

36 This serves not only to complete the rhythm but also to break any monotony which may arise from the frequent repetition (Swartz 1956:29-31).

37 Item 7, Dickie (2017:279.

38 Item 17, Dickie (2017:258).

39 See Item 12a, Dickie (2017:282-3).

40 In the Shembe church, songs adhere to a strict rhythm to provide for the call-response format as well as staggered vocal entrances (Muller, 2010). See also Brown, 1998:148.

41 Despite the focus in the literature on the "the polymetric character of African music", Chernoff (1979:115) notes that this has been somewhat abandoned, with a single beat taking the major role in the appreciation of African music.

42 As Alan Merriam (1982) observes: "The main beats never coincide."

43 As the German composer and educational musicologist, Carl Orff, notes, the rhythms inherent in a person's native language determine the musical rhythm. See Locke, 2009.

44 Cited by Chernoff (1979:49-50).

45 This is in line with the principles of orality and poetics. See Dickie (2017), chapters 3 and 4.

46 Video version: Item 51, Dickie (2017).

47 See Item 12a, Dickie (2017:282-3).

48 Cf. Dargie (1986:259) who notes that a performer may have to "sing, clap, and dance to different rhythms, while the uhadi bow appears to beat a different rhythm entirely".

49 For example, see Item 6, Dickie (2017:277).

50 Kodaly argues that music is "nourishment", and appeals not only to the emotions but to the intellect also (Szonyi:35:69).

51 As Kodaly (1967) insists, music belongs to everyone.

52 Dickie (2017).

53 One participant was singing her translation in the taxi, and received positive commendation.

54 This is not the main issue in this article, rather the focus is on translating in a way that permits easy singability. Nevertheless, the study worked with "amateur volunteers" rather than professional Bible translators, which is another dimension to the research. Indeed, the advantages of "crowd sourcing" with "amateurs" are many. See Dickie (2017:05-212).

55 See Iser (1974). Performance theory argues that there is no one correct version (Finnegan, 1988:51).