Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.116 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/115-0-1287

ARTICLES

Religiosity in South Africa: trends among the public and elites

Hennie Kotzé; Reinet Loubser

Centre for International and Comparative Politics Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

This article uses statistical data from the World Values Survey (WVS) and the South African Opinion Leader Survey to examine religiosity among the following samples of South Africans: Afrikaans, English, isiXhosa and isiZulu speaking Protestants, Catholics, African Independent Church (AIC) members and non-religious people (public and parliamentarians). We find that mainline Protestant churches have suffered a loss of members, thus changing the denominational face of the country. Additionally, although South Africans remain very religious, the importance of God in their lives has declined. For many people God is now less important although not unimportant. Parliamentarians appear unaffected by these changes: God is still highly important to members of parliament who profess Christianity (the majority). However, the small number of parliamentarians who are not religious now think God is unimportant.

Key words: South Africa; Religiosity; Secularisation; Christianity; Values

Introduction

The South African constitution is often described as the envy of the liberal world due to its progressive acknowledgement and protection of human rights. The constitution is the product of a political transition initiated and implemented by South African elites and it grants equal rights to life, equality, freedom and dignity to all citizens. The law of the land disallows discrimination on the grounds of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or religious background (see Chapter 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996:6-9). However, the South African public has often been characterised by more conservative and traditional belief systems whose values may conflict with the secular, liberal values of the constitution. The institutionalisation of South Africa's constitutional values has thus led to a series of controversial laws that have not always received support from members of the public (Thoreson, 2008). These laws include, for example, the revocation of capital punishment (Mkhondo, 2014) and the legalisation of abortion (Mncwango and Rule, 2008:6-7) as well as same sex marriage (Fabricius, 2014; Rule, 2004:4-5). These legal decisions have continued to cause heated debate, as recent controversies over the acceptance (or not) of gay people and same sex marriage in the Dutch Reformed Church and the Anglican Church attest to (Oosthuizen, 2015; Laganparsad, 2016:5).

This article uses the latest and most comprehensive survey data - in the form of the World Values Survey (WVS) and the Elite Survey - to analyse statistically the extent and nature of South Africa's religiosity and Christian beliefs in particular. According to Norris and Inglehart (2011:13-17), there is a tendency for societies to grow more secular as they become richer and more secure. These wealthy societies are no longer concerned with material survival but rather with post-material values of self-expression and good aesthetics. They also tend to become more tolerant of previously taboo practices such as abortion and homosexuality (Norris and Inglehart, 2011:173-178). Norris and Inglehart's use of the WVS in their extensive research on changing values around the world forms the foundation for this study's examination of where South Africa is positioned with regards to religiosity and liberal values as discussed above.

To measure religiosity and values, comparisons are made between Protestants, Roman Catholics, members of the African Independent Churches (AICs) and people who define themselves as not having a religious denomination (therefore considered non-religious). A further distinction is made between Afrikaans speakers, English speakers, isiXhosa and isiZulu speakers. Lastly, wherever possible the public attitudes are compared to the beliefs of South African elites (with data from the South African Elite Survey). We believe our findings are relevant to anyone interested in the role that religion plays in South African society.

Data and Samples

The data on the public's beliefs are drawn from the 2006 and 2013 waves of the WVS. The WVS is a global time series study that also allows for country-specific questions. It is the largest and most extensive survey of its kind and is conducted every 5-6 years (since its inception in 1981). For this study, the latest two data sets (2006 and 2013) of this nationally representative survey are used, in order to evaluate the most recent changes in South African values. In South Africa, the WVS is conducted under the auspices of the Centre for International and Comparative Politics (CICP) at Stellenbosch University. For the 2006 WVS in South Africa, 2 988 South Africans over the age of 16 were interviewed; in 2013, the number of respondents rose to 3 531. These datasets are weighted to reflect demographics accurately and are also within a statistical margin of error of less than 2% at the 95% confidence level.

The CICP is also responsible for the South African Opinion Leader Survey: a longitudinal study of South Africa's most influential opinion leaders. The data on South African elites is taken from the Elite Surveys that were carried out in 2007 and 2013 (making them comparable to the WVS of 2006 and 2013). Although the 2007 Elite Survey includes respondents from across various sectors (parliament, media, business, etc.), the 2013 Elite Survey only surveyed members of parliament. This study will therefore only analyse members of parliament from both surveys in order to make the samples comparable. The 2007 survey includes 100 respondents and the 2013 survey 142.1 With the use of the Elite Survey it will be possible to compare how the values of parliamentarian elites - who make South Africa's laws and help govern the country - differ from that of the public. However, while the WVS can be used to make generalisations about the public's beliefs and attitudes, the Elite Survey cannot. It only indicates the values of some members of parliament and should not be used to make assumptions about broader public or elite beliefs in the country.

This article uses the datasets discussed above in order to examine the values of some of South Africa's Christian communities and compare them to the non-religious. The Christian communities in question are Protestants, Roman Catholics and members of the AICs.2 The non-religious category consists of respondents who do not belong to any religious denomination (Christian or otherwise) and may or may not be atheist. The elites are divided into the same religious denominations, except AICs. This is due to the fact that so few members of parliament belong to the latter - the sample size is therefore too small to be useful for statistical analysis.

In order to shed additional light on the findings, respondents from the WVS have also been categorised according to their home language. For the purposes of this study, the four biggest language groups in the country are analysed: the Afrikaans-speaking communities, English speakers and speakers of isiXhosa and isiZulu.3 It is regrettable that all eleven language groups could not be included, but such an extensive study is not within the scope of this article. Nevertheless, the general analysis of religious groups includes speakers of all languages. It is only the more detailed analysis of language groups that excludes Christians and non-religious people who speak languages other than Afrikaans, English, isiXhosa or isiZulu. It is also important to note that the various language groups should not be confused with ethnic groups, especially in the case of mother tongue Afrikaans and English speakers. Both these groups in particular are ethnically diverse and it is of paramount importance not to confuse an Afrikaans or English speaker with someone of ethnic Afrikaner or English background. The same warning may apply to isiXhosa and isiZulu speakers although these groups enjoy much more overlap between language and ethnicity.

Moreover, the elites were not divided according to language groups as the samples would then be too small for statistical analysis. The elite samples tend to be small in general (with the exception of Protestant elites) and this may skew the results. Despite this limitation it was still considered worthwhile to analyse the elites according to religious denomination as the data at hand is the best and only source of information with which to study these groups. Finally, please note that all figures have been rounded for convenience and may thus not always add up to 100%.

Religiosity

A quick glance at the four religious groups - Protestant, Roman Catholic, AICs and non-religious - already reveals some changes in their composition from 2006 to 2012. The proportion of Protestant respondents in the sample has shrunk considerably from 39% to 22%. Whereas Catholic respondents used to comprise 16% of the sample in 2006, they now comprise 25%. The IACs have remained about the same (23%-26%) while the proportion of non-religious people has increased slightly: 22%-27%. As of 2013 mainline Protestants are no longer the biggest Christian group in South Africa. Instead, the Christian groups included in this study are now more or less equally large.

Despite the large number of Catholic and IAC Christians to be found among the public, the Protestant religion still dominates among South Africa's parliamentary leaders. Protestant elites have increased in proportion from 65% in 2006 to 77% in 2013. Catholics now comprise 10% of elites as opposed to 14% in 2006. Proportionally speaking there are also fewer non-religious people among the elite sample in 2013: 14% instead of 21%.

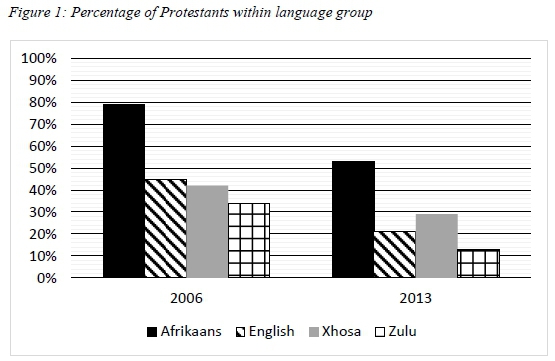

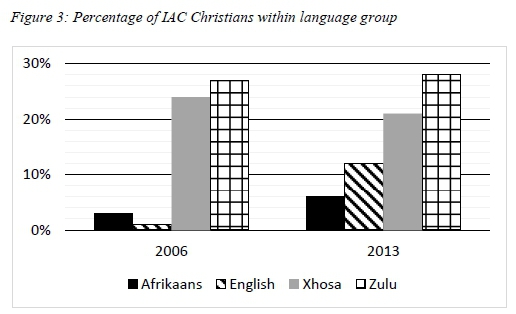

It is possible to describe the changes in religious denomination in more detail with bivariate analysis (cross-tabulation) of religious denomination and language group. This analysis indicates that the Protestant churches have suffered significant proportional losses among every language group under study. Protestant churches used to be the churches of choice among every language group: Afrikaans (79%), English (45%), isiXhosa (42%) and isiZulu (34%). However, by 2013 Protestant churches managed to retain only 53%, 21%, 29% and 13% of these followers respectively. Protestant churches remain the preferred option of the Afrikaans-speaking communities, who also form the bulk of its worshippers (43%) (isiXhosa comprise 27% and isiZulu 20%). Protestant churches also remain the favourite churches of those isiXhosa speakers who are still religious (29%) but there is now a similar number of non-religious isiXhosa (33%). Similarly, there are just as many non-religious people among English speakers (34%) than Roman Catholics (the largest denomination among them). IsiZulu speakers also have slightly more non-religious people among them (32%) than worshippers at the IACs or Roman Catholic Church (roughly 27%-28% each). In general, it would appear that other churches and the ranks of the non-religious may have benefitted from the Protestant exodus - see Figures 1-4.

Whereas Afrikaans speakers are the bulk of Protestant worshippers, isiZulu speakers are the most numerous group in every other category, which is unsurprising as isiZulu has the most mother tongue speakers in South Africa (Statistics South Africa, 2011:23). They are therefore the largest proportion of AIC worshippers (58%), Catholics (43%) and the non-religious (42%). Following isiZulu speakers, approximately 27% of IAC Christians speak isiXhosa (down from 41%) and there has been some growth in Afrikaans (3%-7%) and English (1%-9%) -speaking worshippers. In the Catholic Church, Afrikaans and English speakers each make out about 20% of the faithful, with a similar proportion of isiXhosa worshippers (approximately 17%). After accounting for isiZulu speakers, the non-religious category is about 27% isiXhosa (down from 38%), 17% English and 14% Afrikaans.4

Importance of God and other Beliefs

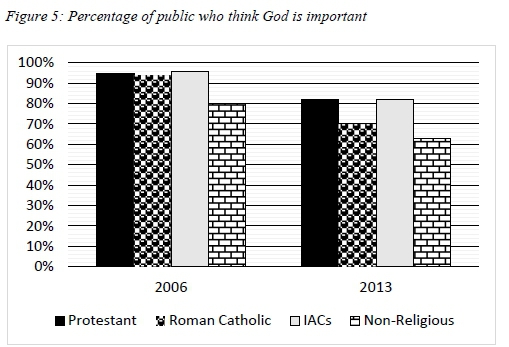

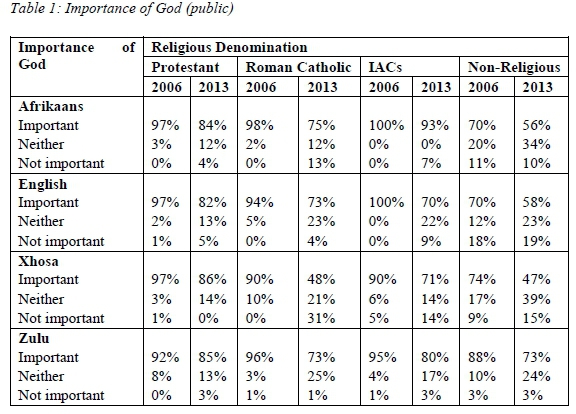

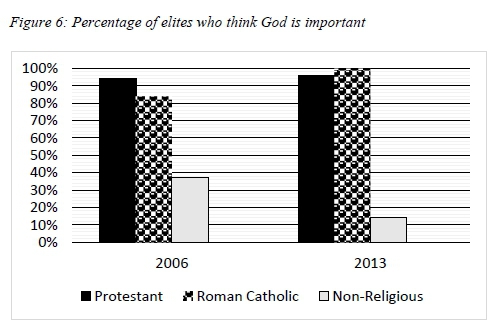

A common question asked in the WVS and the Elite Survey is how important God is in peoples' lives.5 The answers provided to this question show that the importance of God has lessened quite dramatically among everyone: most of the demographics under study reported an approximate 10%-20% drop in people who thought God was very important (see Figure 5 and Table 1). Most of these people evidently now consider God neither important nor unimportant. However, most Christians of all persuasions still consider God to be important while very few people, including the non-religious, think that God is unimportant. It should also be noted that, according to the 2013 data (not shown), almost everyone believes in God (even though isiXhosa and English speaking non-religious people are somewhat less likely to do so). The data for the elites do not indicate the same decline in the importance of God among Christians. In fact, more Christian elites indicated that God was important to them in 2013 than in 2007. On the other hand, non-religious elites are considerably less inclined to rate God as important compared to non-religious people in general (see Figures 5 and 6). The majority of the non-religious elites (64%) now think God is not important (14% disagree and the rest are ambivalent).

In 2013 respondents were also asked various questions which had not been included in the survey previously. These questions are examined below. One such question was whether they believe in hell. The results indicated that a majority of Protestants do (57%), while fewer than half of Catholics (44%) and AIC Christians say the same (45%). As a group, non-religious people showed the least enthusiasm for the belief in hell with an affirmation rate of 39%.6 In general, the belief in hell is strongest among Afrikaans speakers (60%) and weakest among isiXhosa speakers (44%), with English and isiZulu speakers in the middle (54% - data not shown). Further analysis indicated that it is Afrikaans and isiXhosa Protestants in particular who harbour the strongest belief in hell: 84% of the former and 79% of the latter. This is in stark contrast to their Zulu peers: only about 14% of isiZulu Protestants report a belief in hell. In most cases Catholics also report far lower support for the idea: English Catholics are most likely to believe (52%) but fewer than half of other Catholics do, with isiXhosa speakers being the least convinced (27%). Most isiXhosa -aside from Protestants - appear to be decidedly sceptic, as can be seen in Figure 7.

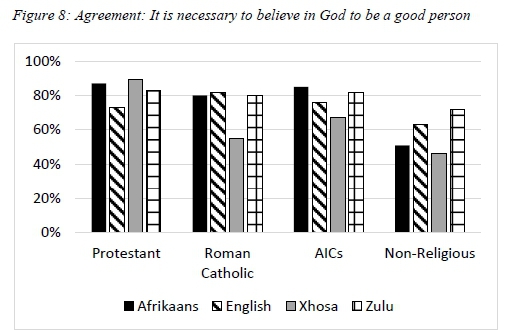

When asked whether it is necessary to believe in God in order to be a moral person and have good values, most of the South Africans in our sample said yes. Approximately 76%-82% of all Christians agreed with this statement. A majority of 64% of non-religious people also agreed (data not shown). Further analysis revealed a similar pattern: agreement is generally high among committed Christians and somewhat lower among those who are not particularly religious. The only exception is isiXhosa Catholics, only 55% of whom supported the statement - a rather low figure under the circumstances. Also to be noted is that non-religious Afrikaans and isiXhosa speakers are stronger in their rejection of the idea that one needs to believe in God to be a good person (see Figure 8).

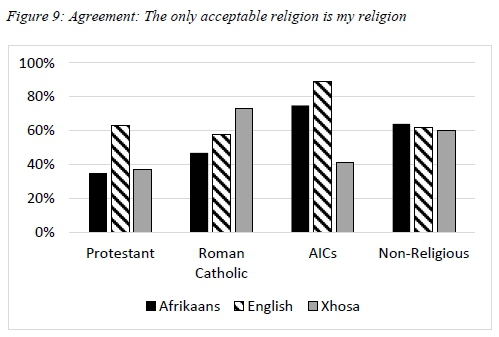

Catholic and AIC respondents were slightly more likely to agree with the next statement: "The only acceptable religion is my religion." Their levels of agreement (69% and 65% respectively) were higher than that of Protestants (54%). This is probably due to the high level of support for the statement found among isiXhosa Catholics, as well as strong support from AIC Christians in general (excepting isiXhosa worshippers). Surprisingly, the levels of agreement to this statement were also quite high among the non-religious respondents (Figure 9).7

There was a high level of agreement among everyone (76%-84%) that all religions should be taught in schools. Among the different language groups, all isiZulu speakers showed very high levels of agreement (85%-95%). However, agreement was generally high among everyone, with well over half of all groups approving (data not shown). Similar results were found for the final statement: "People who belong to other religions are probably just as moral." Everyone overwhelmingly agreed (approximately 81%-88% of Christians and 79% of non-religious people). There was also high agreement among the various language groups: the lowest agreement was among English speaking Catholics (a high 75%) while all English speaking Protestants in the sample were in agreement (data not shown).

Concluding Remarks

This essay provides a descriptive overview of religiosity among the samples of South Africans chosen for this study: Afrikaans, English, isiXhosa and isiZulu-speaking Protestants, Catholics, AIC members and non-religious people. Two main findings stand out from the data: the proportional changes in denomination and the somewhat lesser importance of God. South Africa's Protestant churches appear to have suffered an exodus of members. To a certain extent, the other churches may have benefitted from the situation since their proportion of the flock has grown in proportion to Protestant losses. Despite also suffering big losses of Afrikaans speaking members, the Protestant churches remain in favour among the Afrikaans communities. These communities have always been an important source of followers for the Protestant churches, but are now its largest source.

It is also clear from the data that although South Africa remains a very religious country, with most people of every description (including the non-religious) believing in God and considering God important in their lives, this importance has been on the wane. Fewer people, including Christians, consider God to be very important. Nevertheless, the number of people who consider God to be unimportant remains very small. God has therefore become less important to some people, but by no means unimportant. South African elites appear to have been unaffected by these changes among the general population: God is still highly important to those of the country's parliamentarians that profess Christianity, which happens to be the majority. The same cannot be said of the smaller number of parliamentarians who are not religious: the majority of the non-religious elites now think God is unimportant. It remains to be seen whether these trends will continue in the future, but they are clearly important indicators of social and perhaps political value change in South Africa.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. 1996. Chapter 2: Bill of Rights. Pretoria: Government Printer. 6-24. [ Links ]

Fabricius, P 2014. "Just how Serious is South Africa about Gay Rights?" ISS Today. 27 February. https://www.issafrica.org/iss-today/just-how-serious-is-south-africa-about-gay-rights (2 March 2016). [ Links ]

Laganparsad, M 2016. "Church Welcomes Gay Couples but still Refuses Marriage Rites" in The Sunday Times. 28 February. 5. [ Links ]

Mncwango, B and Rule, S 2008. "South Africans against Abortion" in HSRC Review. 6(1). 6-7. [ Links ]

Mkhondo, R 2014. "Let's be Democratic about Death Penalty." IOL. 29 October. http://www.iol.co.za/the-star/lets-be-democratic-about-death-penalty-1772385 (2 March 2016). [ Links ]

Norris, P. and Inglehart, R 2011. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, J 2015. "Gay-Besluit Gestuit." Netwerk24. 14 November. http://www.netwerk24.com/Nuus/Algemeen/gay-besluit-gestuit-20151114 (22 February 2016). [ Links ]

Rule, S 2004. "Rights or Wrongs? Public Attitudes towards Moral Issues" in HSRC Review. 2(3). 4-5. [ Links ]

South African Institute of Race Relations, 2015. South Africa Survey 2015. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2011. "Census 2011: Census in Brief." http://www.statssa.gov.za/census/census_2011/census_products/Census_2011_Census_in_brief.pdf (2 March 2016). [ Links ]

Thoreson, RR 2008. "Somewhere over the Rainbow Nation: Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Activism in South Africa" in Journal of Southern African Studies. 34(3). 679-697. [ Links ]

1 In the 2007 data set, approximately 52% of respondents were members of the ANC, 25% were DA members and 7% belonged to the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). The rest of the sample belonged to various other small parties. In 2013 approximately 44% of the members of parliament interviewed belonged to the ANC, 41% to the DA, 10% to the Congress of the People (COPE) and 5% to the IFP. The samples were not weighted and are not representative of each political party's proportion of seats in the national assembly.

2 These three denominations form the biggest Christian groups in the country and Christianity is by far the most common religion in South Africa (South African Institute of Race Relations, 2015:69).

3 According to the 2011 census, isiZulu has 11 587 374 mother tongue speakers, followed by isiXhosa (8 154 258), Afrikaans (6 855 082) and English (4 892 623) (Statistics South Africa, 2011:23).

4 It should, however, be kept in mind that only four language groups are included in this analysis. In reality, there are also speakers of other languages among the Christian and non-religious groups.

5 Unlike the other (yes/no) questions analysed in this article, the importance of God was originally answered on a ten point scale with 1 indicating that God was not important and 10 indicating that God was very important. These response categories have been recoded to group answers into three categories: values 1-4 were recoded as 1 (not important), 5-6 as 2 (neither) and 7-10 as 3 (important).

7 The data for isiZulu speakers was not statistically significant and was thus excluded from this analysis. A test of statistical significance indicates whether the results occurred by chance or not. If there is a chance that the results only occurred by chance (as with the isiZulu speakers above), it is unfortunately necessary that it be excluded.