Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.115 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/115-0-1285

ARTICLES

Jesus 'the word' as creator in John 1:1-3: help for evolutionists from Philo the Hellenistic Jew

Annette Evans

University of the Free State

ABSTRACT

Philo's Hellenistic Jewish background (c. 50 BCE - 30 CE) helps to clarify John's identification of Jesus as the 'Logos'. This article explores the course of the Hellenistic philosophical context in which the use of the word 'Logos' was developed from the idea that truth could only be grasped through reason. In Ionia, Heraclitus (c. 500 BCE) was the first to use the term Logos as the principle of balance, stability, and order. Philo's exegesis of Gen 1:26- 27 and Gen 2:7 develops Jewish Wisdom traditions in terms of ' Logos' as present in humanity as a mediator. Thus Philo affirms the transcendence of the creator and at the same time his accessibility to the world he has made. The fertility of John's use of the word Logos harmonises with such mysterious New Testament phrases as 'Christ in you.'

Key words: John 1:1-3; Logos; Philo; Creation; Hellenism; Evolutionists

Introduction and Methodology

The prologue in John's gospel makes an astounding claim about Jesus Christ, the man of flesh who 'lived among us':

'In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being ... and the Word became flesh and lived among us' (John 1:1-3, 14a).

How, in today's scientific and technological cultural context, are we to make sense of the above text? In the first place, 'Word' is a poor translation of the original Greek word 'Logos'. Unfortunately there is no directly translatable word in any language other than Greek, because the word Logos arose from a complex development of Hellenistic philosophy which was still current in the era when John's gospel was written. To get to the bottom of what John meant by the word ' Logos' the cultural context of his use of this word must be unravelled. John's description of Jesus Christ as the Logos and Creator of 'All things' encompasses not only a specific aspect of the concept of Wisdom in the Hebrew Bible, but also aspects of Hellenistic philosophy.

Philo of Alexandria (c. 30 BCE-50CE) provides the explanatory link because in the writings of Philo, 'the two great traditions of biblical and Greek thought first meet and interact with each other in a profound way' (Runia 2001:577). In order to explicate the connection from Philo 's combination of the biblical concept of creation of the world with his understanding of Hellenistic philosophy to John's use of the word Logos, the following modus operandi was followed. Firstly, the development of the original Greek word Logos was traced back to its origin in the Greek philosopher Heraclitis (c. 550-480 BCE). Secondly, the connection between the concept in the Hebrew Bible of Wisdom as implicated in God's creation of the world was explored in terms of Proverbs 8. Thirdly, the relevant writings of Philo, the devout Hellenistic Jew, were read closely to gain an understanding of how John could use the word Logos in the sense of Creator of 'All things.'

Hence this article takes a linguistic and theological approach briefly to present relevant aspects of ancient Greek philosophy and of the biblical concept of Wisdom as portrayed in Proverbs 8, both in the Hebrew Bible and the LXX. Pertinent excerpts from Philo's exegesis of Gen 1:26, 27 and 2:7 in terms of Hellenistic philosophy are presented in order to demonstrate coherent connections to John's concept of Jesus Christ as the pre-existent Logos and Creator.

Ancient Greek Philosophy

Alexander (2003:4) suggests that the debate about the creation of the world spread westwards to become a generalised search in the ancient Near East for an overarching concept of the underlying order which was believed to be common to all things in the physical world. For instance, more than five hundred years before the birth of Christ, Pythagoras (c.532 BCE) had so carefully observed natural phenomena that, by applying abstract reasoning to his observations he arrived at the realisation that the world was a sphere. It was his combination of close observation of nature with a preoccupation with geometry that enabled him to discover the simple numerical relations of musical intervals. At about the same time in Ephesus, the philosopher Heraclitus (c.550-480 BCE) propounded the idea that the opposites so clearly perceptible in the world, are actually in balance and stability in an orderly way. He came to the conclusion that the world is a balanced adjustment of opposing tendencies so that even though all things are in flux, behind the strife between opposites is a hidden harmony. Heraclitus named this principle of balance, stability, and order, the Logos.

By the time that Socrates (470-399 BCE) was born in 470 BCE the fundamental principle of Greek thought, that the universe is orderly, was well established. In harmony with that principle, Socrates believed that mankind's ability to reason was the only solid foundation for knowledge. His pupil Plato (428-347 BCE), like Heraclitus, recognised the flowing quality of everything tangible in nature, but he was concerned with what is eternal and immutable, not only in nature but also in society and in morals. True to the already established Greek tradition, Plato asserted that 'reason', as opposed to 'feeling', is the only way of gaining true knowledge because reason expresses what is eternal and universal (Gaarder 1995:54-55, 65-69).1 Plato's pupil Aristotle (384-322 BCE) considered mankind to be at the top of a 'scale' of living beings because mankind has the ability to think rationally, and therefore has a spark of divine reason. This idea provides the crucial link to Philo's exegesis of Gen 1:26-27.

Diachronically, the next major development in Greek philosophy that is of relevance is early and Middle Stoicism, which arose in c. 335 BCE. By then Alexander the Great had conquered virtually the entire ancient Near East and the influence of Hellenism was everywhere. Stoicism upheld Plato's claim that what is eternal and immutable is that which is attained by reason, rather than the senses. Consequently Heraclitus's concept of the Logos as the spark of divine reason which every human being possesses came to prominence. Stoic philosophy propounded the belief that in order to achieve perfection, mankind should live in accord with rational nature. Because it is the rationality of the Logos that maintains order, balance and stability, the correct and fitting act was to be controlled by the Logos. Consequently the Logos came to be viewed as a god (Ferguson 1993:336). It must be noted that in Stoicism the Logos was an impersonal god - for Stoicism the goal of humanity was self-liberation (Ferguson 1993:336-337).

The Stoics claimed that because mankind has the ability to reason, the Logos is an inherent quality possessed by every human being; in other words, each person has part of the Logos within him/herself. Over the next two hundred years in Stoic circles the term Logos was understood as a link which connected the Absolute with the world and humanity. The chief Stoic, Posidonius, lived during the century before the birth of Christ (c.135 BCE-c.50 BCE). He was interested in causation and observed the natural world very closely. For instance, it was Posidonius who discovered the effect of the moon on the tides by correlating the heights of the tide with the phases of the moon. Consequently, he came to the conclusion that there is a sympathetic relationship between all parts of the world. 2Under Posidonius's influence the term Logos became widespread because of the desire to conceive of God as transcendent and yet immanent at the same time (Goodenough 1969:139).

Wisdom and Creation in the Hebrew Bible

The 'wisdom writings,' Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Ben Sirach and Wisdom of Solomon generally reflect the dominant concerns of how to deal with daily experience and how to

cope with it (Metzger & Murphy 1994:623-624). The Jewish sages responsible for the Wisdom books were keen observers of the world around them, and they extended these observations to play an integral role in moral formation; the two aspects went hand in hand (Brown 2014:9, 16, 17). The Mosaic approach to Wisdom was that mankind should not question the ways of God, but by the 5th century BCE Jewish Wisdom writings 'reflect a lively debate about the physical world' (Alexander 2003:4). In Proverbs 8 Wisdom  is personified, and in verse 22 Wisdom claims to have been created by

is personified, and in verse 22 Wisdom claims to have been created by  at the beginning of creation. The NRSV notes an alternative reading: not 'at', but 'as' the beginning of creation. The latter version is confirmed in the LXX.3 Whatever the original reading, the implication that Wisdom was intimately connected to

at the beginning of creation. The NRSV notes an alternative reading: not 'at', but 'as' the beginning of creation. The latter version is confirmed in the LXX.3 Whatever the original reading, the implication that Wisdom was intimately connected to  at the time of creation of 'the heavens and the earth' (Gen 1:1) is consistent with Proverbs 8:27 'When he established the heavens, I [Wisdom] was there.' Thus one can recognise the source of the statement in John 1:1b 'and the Word (Logos as Wisdom) was with God.' It is Philo's exegesis of Gen 2:26, 27 and 2:7, presented below, that provides the explanation of how John made the equation between the Old Testament's use of the words

at the time of creation of 'the heavens and the earth' (Gen 1:1) is consistent with Proverbs 8:27 'When he established the heavens, I [Wisdom] was there.' Thus one can recognise the source of the statement in John 1:1b 'and the Word (Logos as Wisdom) was with God.' It is Philo's exegesis of Gen 2:26, 27 and 2:7, presented below, that provides the explanation of how John made the equation between the Old Testament's use of the words  Wisdom with the Greek word

Wisdom with the Greek word  .

.

Philo c.30 BCE-50 CE

Philo's life overlaps with the time when Jesus lived on earth. Philo, the devout Jew and Hellenistic intellectual who understood the Mosaic religion in terms of Greek philosophy, lived and worked in Alexandria. Alexandria had been the intellectual hub of the Hellenistic world for centuries before the birth of Christ (see Evans 2004:294). In order to present a more complete picture of the ideas and cultural factors which contributed to the use of the word Logos, the ancient Egyptian background must be taken into consideration. Metzger & Murphy (1994:802) for instance note that most scholars agree that the second collection of proverbial sayings, 'The Words of the Wise' in Proverbs 22:17-23:11 is 'in some way dependent upon the Instruction of the Egyptian sage, Anmen-em-ope.' In the mythology of the culture from which Moses led the Hebrew people, it was through the 'heart and tongue' of Ptah that the world was created, that is, his words, or utterance. Ptah, the most ancient and pre-eminent of gods, was the god of Memphis, the ancient political capital of Egypt (Hart 1990:18). In Memphite mythology, Ptah coalesces with the deity which emerged from the primeval waters. Just as in Genesis 1:2 'the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters' , 4 so in Memphite theology a limitless ocean of water was imagined as having existed in darkness before the development of a structured cosmos.5

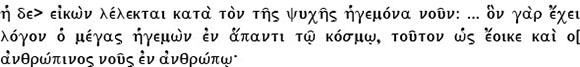

Amongst Philo's prolific writings there are explanations of the account of the creation of mankind in Genesis in terms of the Greek philosophical idea of the Logos. For Philo, the Logos is the instrument of God in the creation of the world because it is 'the divine reason-principle, the active element of God's creative thought (Isaacs 1992:197).' In De Opificio Mundi 69 (trans. Colson & Whitaker 1929:55) Philo explains that God has bestowed his own intellect upon mankind in the form of the  (the human mind):

(the human mind):

'... it is in respect of the Mind, the sovereign element of the soul that the word 'image' is used; ... for the human mind  evidently occupies a position in men precisely answering to that which the great Ruler

evidently occupies a position in men precisely answering to that which the great Ruler  occupies in all the world.'6

occupies in all the world.'6

Thus, here Philo interprets the term  (image) to mean the soul's director or intellect; it is this specific aspect in which humankind stands in an image relation to God (Runia 2001:235). This concept becomes clearer in Philo's exegesis of Gen 1:26-27 and 2:7 in De Opificio Mundi 134 (trans. Runia 2001:82):

(image) to mean the soul's director or intellect; it is this specific aspect in which humankind stands in an image relation to God (Runia 2001:235). This concept becomes clearer in Philo's exegesis of Gen 1:26-27 and 2:7 in De Opificio Mundi 134 (trans. Runia 2001:82):

'After this he [Moses] says that God moulded the human being, taking clay from the earth, and he inbreathed onto his face the breath of life [Gen 2:7]. By means of this text too he shows us in the clearest fashion that there is a vast difference between the human being who has been moulded now [Gen 2:7] and the one who previously came into being after the image of God [Gen 1:27]. For the human being who has been moulded as sense-perceptible object [Gen 2:7] already participates in quality, consists of body and soul, is either man or woman, and is by nature mortal. The human being after the image [Gen 1:27] is a kind of idea or genus or seal

, is perceived by the intellect, incorporeal, neither male nor female and is immortal by nature.'

In De Opificio Mundi 139 Philo emphasises the differences between the human being formed in Gen 1:27 as 'idea' with that formed in Gen 2:7 as 'physical creation':

'for the Creator, we know, employed for its [the soul's] making no pattern taken from any created thing, but solely, as I have said, His own Word

.' Trans. Colson & Whitaker (1929:111).

In De Opificio Mundi 135 and De Gigantibus 52 Philo describes the Logos as the 'High Priest'/'archangelos'  , and then unfortunately (because it is easily misconstrued), in Questiones et Solutiones in Genesis II.62 (trans. Colson & Whitaker 1929) Philo goes further and actually calls the Logos 'the second God':

, and then unfortunately (because it is easily misconstrued), in Questiones et Solutiones in Genesis II.62 (trans. Colson & Whitaker 1929) Philo goes further and actually calls the Logos 'the second God':

'Why does (Scripture) say, as if (speaking) of another God, "in the image of God He made man" and not "in His own image?" Most excellently and veraciously this oracle was given by God. For nothing mortal can be made in the likeness of the most high One and Father of the universe but (only) in that of the second God, who is His Logos

. For it was right that the rational (part) of the human soul should be formed as an impression by the divine Logos, since the pre-Logos God

is superior to every rational nature. But he who is above the Logos (and) exists in the best and in a special form - what thing that comes into being can rightfully bear His likeness?'7

However, in Heres. 205 the idea is qualified to make it clear that the Logos is a mediating element between God and mankind:  ...

...

'To His Word, His chief messenger ... to stand on the border and separate the creature from the Creator. This same Word (both pleads with the immortal as suppliant for afflicted mortality and acts as ambassador of the ruler to the subject).' Thus, by virtue of its presence in humanity, the δευτερος θεός as the Philonic Logos should be understood in its mediating characteristic. The exegesis of Gen 1:26-27 and 2:7 provides the background to what Runia (2001:327) noted was Philo's frequent use of the term μεθόριος to denote the intermediate position of human beings in general. For instance, in De Opificio Mundi 135 Philo unifies the two accounts of the creation of mankind with the concept of the Philonic Logos as the μεθόριος (mediator):

'To His Word, His chief messenger ... to stand on the border and separate the creature from the Creator. This same Word (both pleads with the immortal as suppliant for afflicted mortality and acts as ambassador of the ruler to the subject).' Thus, by virtue of its presence in humanity, the δευτερος θεός as the Philonic Logos should be understood in its mediating characteristic. The exegesis of Gen 1:26-27 and 2:7 provides the background to what Runia (2001:327) noted was Philo's frequent use of the term μεθόριος to denote the intermediate position of human beings in general. For instance, in De Opificio Mundi 135 Philo unifies the two accounts of the creation of mankind with the concept of the Philonic Logos as the μεθόριος (mediator):

' the sense-perceptible and individual human being has a structure which is composed of earthly substance and divine spirit, for the body came into being when the Craftsman took clay and moulded a human shape out of it,8 whereas the soul [Gen 1:27] obtained its origin from nothing which has come into existence at all, but from the Father and Director of all things. Not included: 'What he breathed in [Gen 2:7] was nothing else than the divine spirit which has emigrated here from that blessed and flourishing nature for the assistance of our kind, in order that, even if it is mortal with regard to its visible part, at least with regard to its invisible part it would be immortalized.' For this reason it would be correct to say that the human being stands on the borderline between mortal and immortal nature (

). Sharing in both to the extent necessary, he has come into existence as a creature which is mortal and at the same time immortal, mortal in respect of the body, immortal in respect of the mind' (trans. Runia 2001:82).

The ability of the Logos to be a perfect mediator is clarified by Philo's apt use of allegory in Quis Rer. 230, 231 (Colson & Whitaker 1932:278) where he uses the word 'Logos' in association with birds in their qualities of having wings and 'soaring', equating these qualities with the two forms of reason - 'the archetypal reason above us' and the copy of it (μίμημα) which human beings possess. This is done in the context of the indivisibility of the bird in Gen 15:10b:  'but he did not cut the birds in two' (NRSV); as the bird, so the Logos is indivisible.

'but he did not cut the birds in two' (NRSV); as the bird, so the Logos is indivisible.

Discussion: John's use of Hellenistic Concepts

Radice (2009:139) noted that in the Judeo-Hellenistic setting in the prologue of the Gospel of John there is an 'extraordinary philosophical affinity' between the Stoic concept of the creative Logos as the chief rational principle responsible for the creation of the cosmos and the creative word in the Bible. Platonism is employed as a bridge to make the vital link in Philo's rationale for mediation between God and mankind. For Philo, the Logos is and thus the instrument of God in the creation of the world (Isaacs 1992:197). Radice (2009:136) finds the source of Philo's concept of the Logos in De Opificio 24:

'If one were to use more direct terms, one might say that the intelligible world is nothing other than the divine Logos already engaged in the act of creation. ... and this is the doctrine of Moses, not mine.'

Because to Philo the Logos as 'the divine reason-principle' is the active element of God's creative thought - the power through which God frames the world - he calls it the δεύτερος θεός. Thus the Logos is called the δεύτερος θεός in the sense of making mediation possible between mankind and the deity (Isaacs 1992:196, 197).9 Isaacs stresses that the δεύτερος θεος is the incorporeal Word or Thought of God, definitely not a distinct and separate being subordinate to God. Bousset (1913:389) explains this development of the Logos as medium of creation by means of the concept of a hypostasis: he perceives this to occur where the 'monotheistic idea struggles free from the older polytheism'. The monotheistic tendency 'volatises' originally concrete figures of deities into abstract figures which are half person and half qualities of God, to satisfy the quest for a transcendent, purely spiritual interpretation of God. This reverts back to the Stoic belief that the correct or 'fitting' act is to be controlled by the Logos (Ferguson 1993:335, 337).

The concept expressed by Plato in De Opificio Mundi 135 of the human being standing on the borderline between mortal and immortal nature, as contained in the term μεθοριος, was crucial because it indicated that humankind has the potential to be part of heaven as well as of earth. Philo refers to Deut 5:5a where Moses says 'and I stood between the Lord and you' to explain the status of the Logos; that it is 'neither uncreated as God, nor created as you, but midway between the two extremes, a surety to both sides ... '

The term Logos does not appear at all in the Greek text of the creation account in Genesis, but John conceives of the coming into being of the world in terms of Philo's Hellenistic concept of the presence of the Logos as mediator in humanity as part or spark of God, to convey the mediation between the divine and human world in a new way.

Conclusion

Philo's exegetical development of Jewish Wisdom traditions in terms of Logos allows him to affirm the transcendence of the Creator and at the same time his accessibility to the world he has made, because the Logos is present in humanity itself according to Philo's exegesis of Gen 2:7.10 In Judaism in the Greek-speaking world, especially in Egypt, God was no longer only the God presented in the Old Testament: 'He was the Absolute, connected with phenomena by His Light-Stream, the Logos or Sophia' (Goodenough 1969:7-8).11 The Platonic idea of a demiurge below the highest God was already dominant by the first century BCE, and the Logos was regarded as the medium of creation and government of the world (Fossum 1982:356). Therefore it can be seen that the concept of Jesus Christ as the Logos and Creator as expressed in the Nicene Creed, was not entirely unprecedented. Witherington III (1994:235, 249) assumes that Wisdom became identified with Jesus of Nazareth in the Q tradition, but the apostle Paul was a very important facilitating link in the reception of John's understanding of Christ as the Logos and creator of the world. Long before Neoplatonism arose, Paul the highly educated rabbi and Philo were 'fishing in the same pool' (as Henry Chadwick put it) - they had the Hellenistic Jewish background in common (Ferguson 1993:451, 454).12

That Jesus walked the earth is undeniable, but without Greek philosophy his identification as God and Creator of the world as stated in John 1:1c-2 would not have been possible. Ultimately, when understood in terms of pre-existent Wisdom, John's use of the Greek word Logos brings us a little nearer to understanding the mystery of Jesus Christ as God the Creator, as expressed in the Nicene Creed: being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.'

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, PS 2003. 'Enoch in Millennial Perspective. On the Counter-cultural Biography of an Apocalyptic Hero', in McNamara 2003:1-19. [ Links ]

Brown, WP 2014. Wisdom's Wonder. Character, Creation, and Crisis in the Bible's Wisdom Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan/Cambridge, UK: William B Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Bousset, W 1913. Kyrios Christ. Trans. J Steely. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Colson FH & Whitaker GH (Translators) 1929. Philo. Vol I-V. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Evans, AHM 2004. 'Hellenistic and Pharaonic Influences on the Formation of Coptic Identity.' Scriptura 2:292-301. [ Links ]

Ferguson, E 1993. Backgrounds of Early Christianity. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Fossum, JE 1982. The Name of God and the Angel of the Lord. The Origin of the Idea of Intermediaries in Gnosticism. Utrecht: Drukkerij Elinkwijk BV. [ Links ]

Gaarder, J 1995. Sophie's World. A Novel about the History of Philosophy. (trsl.) Paulette Moller. London: Phoenix House. [ Links ]

Goodenough, ER 1969. Light by Light. The Mystic Gospel of Hellenistic Judaism. New Haven: Repr. Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Hart, G 1990. Egyptian Myths. London: British Museum Press. [ Links ]

Isaacs, ME 1992. Sacred Space. An Approach to the Theology of the Epistle to the Hebrews. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Kamesar, A (ed.) 2009. The Cambridge Companion to Philo. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

McNamarah, M (ed.) 2003. Apocalyptic and eschatological heritage. The Middle East and Celtic Realm. Dublin: Four Courts Press. [ Links ]

Metzger BM & Murphy, RE (eds.) 1994. The New Oxford Annotated Bible. New Revised Standard Version. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mullen, ET Jr. 1980. The Assembly of the Gods. Harvard Semitic Monographs 24. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

Pearson, BA, 1984. 'Philo and Gnosticism,' in Haase, 295-342. [ Links ]

Radice, R 2009. 'Philo's Theology and Theory of Creation' in Kamesar, 124-145. [ Links ]

Runia, DT 1986. Philo of Alexandria. On the Creation and Timaeus of Plato. Leiden:Brill. [ Links ]

Runia, DT 2001. Philo of Alexandria. On the Creation of the Cosmos according to Moses. Introduction, Translation and Commentary. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Russel, B 1960. The Wisdom of the West. A Historical Survey of Western Philosophy in its Social and Political Setting. London: Macdonald. [ Links ]

Wilkinson, RH 1994. Reading Egyptian Art. A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. London: Thames & Hudson. [ Links ]

Witherington III, B 1994. Jesus the Sage: the Pilgrimage of Wisdom. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

1 Bertrand Russell (1960:23) surmised that Pythagoras's application of abstract reasoning to numerical relations is probably what led to the notion that all things are number, which led to Plato's 'theory of ideas' or 'universals' - that it is only the 'intelligible' that is real, perfect, and eternal, and not that perceived by the senses.

2 Posidonius spoke of the sun as a 'life-giving force', a major element of Egyptian mythology. See notes 4, 5. Posidonius saw the cosmos as an ordered world with graduated levels of being, and wrote a work about beings intermediate between human and divine. None of his writings are extant, but they are often referred to in later works. He represented a return to Plato and Aristotle to the extent that Strabo said he was 'always Aristotelizing'. Although Posidonius was not a mystic, he facilitated the development of mysticism (Ferguson 1993:341).

3 Κύριος έκτισε με αρχήν óδών αυτου εις εργα αυτου, (The Lord made me the beginning of his ways for his works).

4 NRSV notes the alternative readings 'while the spirit of God' or 'while a mighty wind.'

5 Heliopolitan mythology is slightly different from the Memphite mythology: Atum, the sun god, arose out of goddess of the heavens, Nut, at the beginning of time to create the elements of the universe. He self-developed into a being and stood on the raised mound, the Benben. As supreme deity Atum was both 'artisan of the human race and commander of order in the universe' (Hart 1990:11, 18, 19).

6 Trans. Colson & Whitaker (1929:55). Runia (2001:227) notes that the phrase  is used of Zeus in Plato's Phaedrus myth, 246e4. The only other place Philo uses it, is for the sun at Op. 116: 'The sun, too, the great lord of the day' (

is used of Zeus in Plato's Phaedrus myth, 246e4. The only other place Philo uses it, is for the sun at Op. 116: 'The sun, too, the great lord of the day' ( ).

).

7 Pearson (1984b:329) suggests that the variety of interpretations found in Philo is probably due to his use of various traditions of exegesis. The idea that the soul is connected with heaven and the body with earth is found in both the Greek Platonic tradition but also in the later Jewish apocalyptic and rabbinic sources.

8 Plato alludes to the creator god as  in Tim. 28A6, but Runia (1986:107) notes that Plato was not the first Greek philosopher to describe γενεσις in terms of a craftsman-creator. This allusion to the Craftsman is made in the syncretistic Alexandrian context where the mythology of Kothar-wa-Khasis of Ugarit (as related to that of Thoth as craftsman in Egypt) was still likely to have been part of general apperceptive mass of the Alexandrian context. Ugarit was destroyed in 1200 BCE, but its mythology has been demonstrated to live on a thousand years later in the book of Daniel (Mullen 1980:160).

in Tim. 28A6, but Runia (1986:107) notes that Plato was not the first Greek philosopher to describe γενεσις in terms of a craftsman-creator. This allusion to the Craftsman is made in the syncretistic Alexandrian context where the mythology of Kothar-wa-Khasis of Ugarit (as related to that of Thoth as craftsman in Egypt) was still likely to have been part of general apperceptive mass of the Alexandrian context. Ugarit was destroyed in 1200 BCE, but its mythology has been demonstrated to live on a thousand years later in the book of Daniel (Mullen 1980:160).

10 By the time of Neoplatonism (205-270 CE) Hellenism had been influenced by a fusion of religions, and that was why a concise and exclusive summary of Christian doctrine had to be devised. The central tenet of the Nicene Creed for instance, is that Jesus is both God who had become man (not a 'demigod'), and truly a man who had shared the misfortunes of mankind and actually suffered crucifixion.

11 Thus for instance Philo can explain Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac in Cher 26-32 (Gen 22:6) in terms of the Pythagorean-Platonism of Alexandria in terms of ascent of the soul in order to be reunited with God, which necessitates severance from the 'sensible' or irrational life (Goodenough 1969:7-8).

12 For instance Eph 3:9: 'And to make all (men) see what (is) the fellowship of the mystery, which from the beginning of the world hath been hid in God, who created all things by Jesus Christ' (KJV).' Interestingly, the NRSV edition does not include 'by Jesus Christ.' It is not certain that Paul wrote the letter to the Ephesians, but it was very likely written at about the same time as the gospel of John, near the end of the first century (Metzger & Murphy 1994: 124, 272). The Nicene Creed per se dates to even later than the Council of Nicene (325 CE), but expresses accurately the belief expounded there that Jesus Christ was 'begotten of the Father before all worlds ... being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.'