Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.114 Stellenbosch 2015

ARTICLES

In search of a theoretical framework towards intercultural awareness and tolerance

MA van der WesthuizenI; T GreuelII; CH ThesnaarIII

IHuguenot College, Wellington Stellenbosch University

IIMusic Didactics Evangelische Fachhochschule Rheinland-Westfalen Lippe Bochum, Germany

IIIDepartment of Practical Theology and Missiology Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

Even if legalised segregation (i.e. Apartheid) has ceased, individuals, groups and communities remain sensitive owing to past experiences. Furthermore communication obstacles lead to on-going misunderstandings that result in mistrust (Williams, 2002:5167). Without a process to stimulate intercultural awareness and tolerance, the legacy of the past cannot be undone. The question therefore is: How can we approach intercultural misunderstanding and mistrust so as to find a way to work towards intercultural awareness and tolerance? The aim of this contribution has been to identify a theoretical framework that could pave the way to finding practical ways of addressing the remaining misunderstandings and mistrust in present-day South Africa. The authors, working from a trans-disciplinary framework, first did a review of the literature in search of a theoretical framework. The contribution concludes with a proposed theoretical framework and some recommendations for further exploration of this topic.

Key words: Awareness; Intercultural Relations; Multicultural Communities; Tolerance; Trans-disciplinary

Introduction

Multicultural communities are a reality in our present-day society. At an international level, Portera (2008:482) explains this phenomenon in terms of the influence of technology and the media, "...increasing geo-political changes and a greater mobility that leads to new and diverse migration tendencies". Apart from the above-mentioned influences, the diverse nature of the South African society is illuminated by its population distribution. According to the most recent statistics, 52.98 million people are living in South Africa, of which 79.8% represents the Black; 9% the Coloured; 8.7% the White- and 2.5% the Asian ethnic groups. It should also be noted that each ethnic group consists of different cultural groups and that a minimum of 11 languages are spoken in the country (Statistics South Africa, 2013). Another aspect to consider is the 2.2 million foreigners living in South Africa, which adds another component to the multicultural dynamics of the country, requiring a paradigm shift to ensure intercultural awareness and tolerance (Statistics South Africa, 2013:3; Mbu, 2014).

Intercultural relations in South Africa have been affected by the segregation laws of the Apartheid system, for example, the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 and the Population Registration Act of 1950. These entailed that different ethnic groups were kept apart, resulting in mistrust and fear (Motloung, 2013:2). With the demise of Apartheid in 1994, it was envisaged that this would be the start of a journey towards social justice and healing. In this regard, the transition period could be perceived as rather peaceful. One effort to deal with the past was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Thesnaar (2012:1) reflects on this and states that: "It was evident that South Africans consciously chose to add 'reconciliation' to the term 'truth commission'. The objective was not merely to deal with the truth, but to work actively towards reconciling the sharply differing sections of society, thereby contributing to building a new nation". The mentioned author concurs that although the TRC tried its utmost to achieve the goal of reconciling the South African nation, it became evident that it required more than one single event. Williams (2002:51-67) explains that even if legalised segregation had ceased, individuals, groups and communities remained sensitive owing to past experiences of a level of misunderstanding that had bred mistrust. Within the South African context, the hurt of the past was simply too deep for the TRC to deal with extensively within the limited time it had at its disposal.

In an effort to contribute to the on-going process of working towards a tolerant South African nation, the authors of this contribution engaged in a process of finding a theoretical framework from which one could identify practical ways to work towards intercultural awareness and tolerance. In the light of the above remarks, this contribution will be structured as follows: firstly, it will explain the trans-disciplinary conversation that informed the contribution; and secondly, it will describe a review of the literature that would inform the choice of theoretical framework. Thirdly it will provide a description of a proposed theoretical framework, which will be followed by recommendations for further exploration of the topic.

A Trans-disciplinary Conversation

As mentioned in the introduction, South African society has not only been challenged by the legacy of Apartheid, but also by its diverse nature. Steyn (2011:7) explains that the country's socio-economic capacities and the demographics of the population contribute to an ongoing struggle to find ways to assist people to live and work together. This author argues that "...the challenge therefore is how to value what different groups may bring to the collective while, at the same time, maintaining cohesive societies". The mentioned challenge may be addressed by different disciplines and in different fields.

This contribution focuses on the disciplines of social work, theology and the arts. The discipline of social work is challenged with comprehending the needs of clients, and addressing these needs within the context of continuous social changes resulting from past intercultural experiences within the Apartheid context, globalisation and migration (Van der Westhuizen & Kleintjes, 2015:120). The discipline of theology is also faced with a challenge to contribute to the healing of relationships. George (2012:5) refers to the term 'intercultural theology' that is seen as a "...response to the post-colonial developments in the world and in the church respectively". With a specific focus on the praxis of theology, the challenge is to find a "... a locus of doing theology in the context of pluralism (i.e. an intercultural context) and globalisation" (George, 2012:17). The arts form a bridge between the challenges faced by the disciplines of social work and theology, serving as a creative tool to create awareness and to promote communication between individuals, groups and communities. The utilisation of the socio-cultural education model in the Arts is specifically aimed at creating opportunities for becoming aware of each other, including differences and common ground (Kinnunen & Kaminski, 2003:7). The European Commission (2014:5) refers to the need to address tensions in intercultural contexts, which places social cohesion at risk. The said Commission's Directorate General for Education and Culture reports that cultural diversity should be viewed as an asset and an opportunity for communities to learn from each other. The Directorate continues to highlight the role of the arts, in that the reality of diverse communities does not only challenge economic and social structures, but also involves symbolic and cultural issues.

As mentioned before, the authors of this contribution came from the disciplines of social work, theology and the arts. As such, a conscious choice was made to work from a trans-disciplinary approach towards finding a theoretical framework for intercultural tolerance and awareness within the South African context. In this regard, Leiner and Flämig (2012:11) particularly favour the concept of 'trans-disciplinarity' above 'inter-disciplinarity,' due to the fact that the latter departs from the concrete co-operation of several disciplines working on a particular topic and functioning as a mere addition. The trans-disciplinarity acknowledges the complexity of conflict and requires continuous cooperation between the different disciplines for solutions. The essence or requirement of this continuous co-operation is to willingly '...accept changes in the orientation of their scholars and the boundaries of disciplines in the process of co-operation' (Mittelstraß, 2005:18-23).1 This requires, more or less, four new research orientations to which the various disciplines need to adhere:

1. The unlimited will to learn from other disciplines and the acceptance to change the concepts and theories of one's own discipline;

2. The gain of inter-disciplinary competence, up to the point where one can productively discuss the work of the other disciplines;

3. The capacity to reformulate the approaches of one' s own discipline in the light of inter-disciplinary competence; and

4. The formulation of a common text in which the unity of trans-disciplinary argumentation replaces the simple aggregation of different results from several academic disciplines.2

In relation to the above, Leiner and Flämig (2012:13) emphasise that trans-disciplinary research as a whole (practical research and the sciences) has to remain aware of being embedded in the life-world (Lebenswelt) in which the sciences and we are living and operating. According to these authors, scientists need to accept that the various sciences are abstractions from the life-world. Scientists can therefore contribute to a common image by discussing the interpretation of the experiences in the life-world (Leiner & Flämig, 2012:14). The above description of trans-disciplinary work informed the authors' approach to find a theoretical framework.

In Search of a Theoretical Framework

The segregated society of the Apartheid-era in South Africa resulted in a lack of awareness between the different groups. This influenced the meaning individuals, groups and communities attached to situations/contexts of others (i.e. a lack of understanding of what is perceived as 'foreign'), thereby guiding social attitudes and behaviour. Gibson and Gouws (2005:2) explain this lack of understanding and assert that although Post-Apartheid South Africa led to a greater mobility between the different cultural groups, divisions between groups remain. These divisions hinder interaction processes, which prevent the different groups from understanding each other. Thus, a lack of awareness makes it difficult to develop an understanding of the whole context in which one functions and therefore, leads to mistrust (Williams, 2002:51-67).

As a result of the mentioned mistrust one possible conclusion is that the lack of understanding is often interpreted (i.e. perceived) as a sense of threat; an expectation of an intention to inflict harm. Although this sense of threat does not imply that there is a definite intention to harm, it impacts seriously on tolerance levels among groups (Gibson & Gouws, 2005:2). Ojambo (2009:3-4) explains that this intolerance is based on political intolerance on the one hand, and on social functioning on the other hand. The author accentuates that political intolerance has often been the cause of violence between members of different political parties, even in the recent past. It is deduced that intolerance could be a result of a perceived threat, based on misunderstanding and mistrust. The experience of being threatened impacts on the achievement of universal human needs (i.e. survival needs) and hampers the move to a better understanding of each other. Examples of areas where human needs are affected could be the following threats:

• Group esteem threat: This is also known as a collective threat that is linked to lower self-esteem, implying that an individual feels threatened because he/she is associated with a group that is being stereotyped (Cohen & Garcia, 2005:566). It refers to anything that represents a threat to a group's sense of worth, value or self-esteem (Branscombe & Wann, 1994:641).

• Distinctiveness threat: This threat refers to something that threatens the uniqueness of a group (Riek, Mania & Gaertner, 2006:337).

• Realistic threats: This is represented by anything that is seen as a potential danger to the economic and physical well-being of a group (Renfro, Duran, Stephan & Clason, 2006:43).

• Symbolic threat: Something that is perceived to be a potential danger to a group' s values, beliefs, norms and general way of life (Stephan, Ybarra, & Bachman, 1999:2225).

Threat, however, was not found to be the main cause of intercultural intolerance in South Africa, according to a study conducted by Ojambo (2009:36). Two strong predictors of intolerance were identified to be the strength of the group's sense of identity and the nature /and amount of contact between cultural groups. The latter would contribute to interaction that has the potential to enhance awareness that can lead to increased tolerance. In terms of social functioning, different social groups are formed based on shared lifestyles, perceptions and experiences (Tropman, Erlich & Rothman, 2008:141). In this contribution, the emphasis is on social intolerance as it is a very specific legacy of our past based on our sense of identity as a group and the nature of the amount of contact between the different cultural groups.

The importance of dealing with the past is accentuated by a report by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation that focused on the South African youth, which points to "...a disconnect and a rising cynicism between younger South Africans, the born-free generation, and this country's past" (Lefko-Everett, 2012:49). It is recommended that the youth should be encouraged to develop an awareness of the past in order to develop a healthy vision of the future. In support of this, Buccus (2013:3) argues that "...defensive work of exposing intolerance and offering legal support to its victims is essential if the political elite are to be brought under social control. But, ultimately, defensive work, as important as it is, is not enough on its own. We also need to develop a positive vision of a more inclusive society".

The importance of developing a clear vision through an understanding of one's own cultural identity and an awareness of other cultural identities thus becomes clear. Professional helpers (for the purpose of this contribution, including the social service and theology disciplines) who aim to create positive change among individuals, groups and communities should therefore find creative ways to include intercultural practices. This entails, among others, community-orientated actions and activity-driven programmes (Du Preez, 2000:48-49). This focus on engaging in an African context implies an intercultural hermeneutical perspective, which Louw (2008:153) describes as dynamic and risky critical openness, without losing the tension between continuity and discontinuity, or the identity of the ultimate (the eschatological truth of the Christian faith) within and through the particular we encounter in culture.

Based on the above discussion, and for the purpose of this contribution, as well as with the focus on professional helpers in the social service and theology disciplines, the above-mentioned actions/programmes should, among others, aim at encouraging 1) intercultural practices, within 2) multicultural communities, with the goal of contributing towards an inclusive African culture. The contribution by the discipline of the arts is to explore possible creative practices that could assist professional helpers in this regard.

Portera (2008:283-284) explains that multicultural communities are those where there is space to practice different cultural activities alongside each other. It also means that the different cultures will be aware of each other and that they will, from time to time, join each other. Intercultural practices mean that communities find a way of developing a shared identity, including the different cultural activities. The latter, therefore, leads to change through shared experiences (United Church of Canada, 2011:1-2). Whitesel (2013:3-4) goes further and distinguishes between the terms 'assimilation' and 'accommodation'. Assimilation is perceived as the situation where one tolerates the other, with one group being viewed as the dominant group. Accommodation refers to when one attempts to develop a common experience where there is no dominant group that directs practices. In this regard, Bosch (1991:452) proposes the term 'inculturation'. Within this term, it is argued that "...a plurality of cultures presupposes a plurality of theologies". This would mean that the common experience in accommodation is taken one step further. The common experience should direct future beliefs and practices. In other words, the groups/communities develop meaning through shared experiences that would lead to an awareness of themselves and others and that this would form the foundation for positive change. This inevitably raises the question of responsibility.

Reflecting on the issue of responsibility, Hope and Timmel (2003:221) address the question of who is responsible for the transformation and healing of a nation. The authors refer to the role of government to provide an infrastructure and opportunities that would enable communities to develop their full potential. This contribution would, however, also wish to emphasise that government cannot be solely responsible, and therefore, civil society (including NGOs and FBOs) should be co-responsible. The former minister in the presidency, Trevor Manuel, very recently (19 September 2013) remarked that the citizenry in our country is passive and not engaged in current South African societal issues. For democracy to flourish, there has to be a strong, active and vocal non-governmental sector, frequently interacting with a responsive government. The role of active citizenry is to continue to put the core issues of healing, justice, reparation and reconciliation on the nation's agenda. The authors of this contribution wish to emphasise that the role of civil society should always be to seek to enter into constructive discourse with government in order to engage with the challenges of individuals, communities and nations in a constructive way.

The accessibility of structures and/or systems (such as the TRC) is one aspect to consider, but in terms of Hertnon's theory (2005) it should also be enabling in nature -meaning that it should relate to the needs of community members to ensure happiness and satisfaction. Danesh (2011:1) supports this viewpoint, arguing that although the concepts of human need, conflict and peace are interrelated, they are often addressed in a fragmented manner. In terms of this author' s argument, one needs to include human needs in efforts to work towards intercultural awareness and tolerance. Intercultural awareness and tolerance are, for the purpose of this contribution, linked to universal human needs. It is concluded that when all human needs are being met, different levels of life are affected and that it essentially leads to a sense of satisfaction. Based on this viewpoint, the potential role of the helping professions is highlighted. Hertnon's theory on universal human needs proposes that individuals, groups and communities (including civil society and government) are supported with eight fundamental needs that are linked with four goals. The first four needs (i.e. physical and mental health, a safe and healthy environment and reproduction) are linked with survival that is needed to attend to the last four betterment' needs (i.e. respect for others, a positive self-image, valuing life and opportunities and doing good deeds for others). Addressing all these needs leads to a holistic approach.

The focus on betterment is related to the assumption that intercultural awareness leads to tolerance. When working towards intercultural awareness and tolerance, the focus is therefore on betterment needs. Once survival needs have been met, one can start to address intra- and interpersonal relations. Zhang (2011:51-52) accentuates that the move towards intercultural awareness begins with a cultural awareness of oneself, and that it requires knowledge and competence in effective and creative communication (i.e. the arts) that should ultimately lead to a better understanding of oneself and of others. For the purpose of this contribution, this better understanding is aimed at the development of tolerance (i.e. acceptance) of other cultural practices.

In conclusion and based on the review of the literature above, the assumption that formed the foundation for the search for a theoretical framework to start a journey towards intercultural awareness and tolerance, is therefore that the development of awareness of one's own culture and the culture of others can lead to an acceptance and tolerance of each other. The rationale for the search for such a theoretical framework is: One legacy of the Apartheid era is the mistrust and sense of threat that remains between cultures. Past segregation led to a lack of understanding of each other, even within the present-day multicultural communities. This lack of understanding still impacts on intercultural relations and prevents a move towards betterment. The proposed theoretical framework that will be discussed in the next section is based on this viewpoint and will be aimed at finding a framework that will contribute to:

• Individual awareness,

• Intercultural awareness and

• Tolerance between cultural groups.

Proposed Theoretical Framework

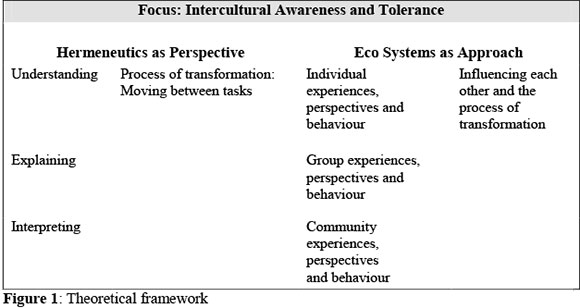

The aim of this contribution was not to find solutions to all societal problems, but rather to explore a theoretical framework from which practical ways to work towards betterment of intercultural relations through awareness and tolerance can be found. Based on the above-mentioned search for a possible framework, the authors made a conscious decision for an intercultural hermeneutical perspective supported by an eco-systemic approach as a possible theoretical framework to address intercultural awareness and tolerance. It is envisaged that it could serve as the conceptual structure (Tavallaei & Mansor, 2010:570) from which these practical ways could be discovered (see figure below).

As illustrated above, this theoretical framework serves as a structural construct based on an intercultural hermeneutical perspective that provides a framework from which applications based on an eco-systems approach can be planned and implemented. The desired outcome is to find practical ways for the helping professionals to assist individuals, groups and communities to develop an awareness of their own, as well as cultural identities of others. This awareness should then contribute to the development of tolerance.

Within the context of this contribution, it is necessary to clarify the terms 'hermeneutical' and 'eco-systemic'. Hermeneutics is the theory that includes written, verbal, and non-verbal communication (Audi, 1999:377). It includes various disciplines in the humanities and social sciences (i.e. trans-disciplinary conversation) and serves as a perspective that illustrates the way one perceives the process that could be used to develop a new understanding of intercultural awareness and tolerance. This process places the emphasis on understanding and interpreting before any contribution to reach intercultural awareness and tolerance should be attempted. This perspective provides a basis (i.e. a process to follow) from which one can identify a suitable approach to find practical applications for practice.

The hermeneutical process could further be described by means of the hermeneutical cycle, which refers to the idea that we can only understand the whole by also understanding the individual parts related to the whole. Neither the whole nor any individual part can be understood without reference to one another, and therefore it is a cycle (Ramberg & Gjesdal, 2005). Taylor (1985:18) explains hermeneutics within an interpretive approach and notes that our understanding of a society is supposed to be circular in an analogous way: we can only understand, for example, some part of a political process if we have some understanding of the whole, but we can only understand the whole, if we have already understood the parts (Anderson, 2005:186). Schockel and Bravo (1998:74) assert that any form of reflection or interpretation must include interaction between the particular and general. In this regard, Shklar (2004:658) points out that interpreters have multiple and sometimes conflicting cultural attachments, yet ". this does not prevent intercultural and/or interdisciplinary dialogue".

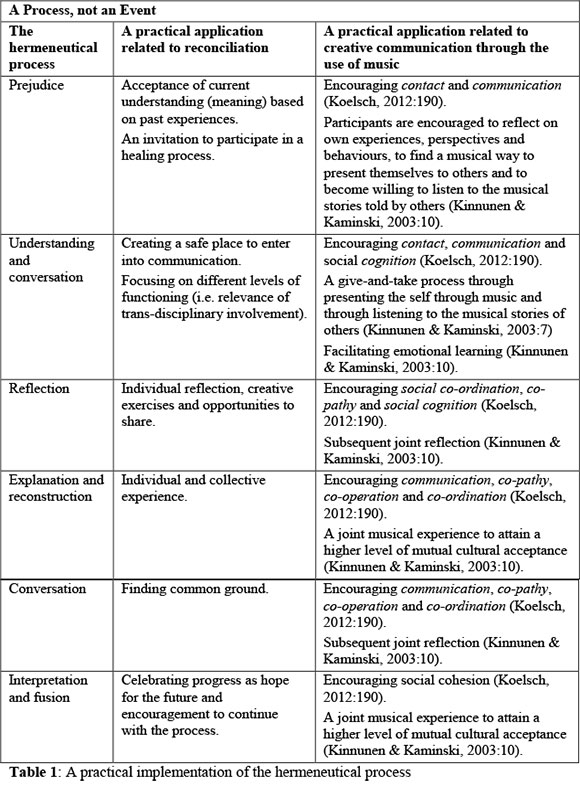

In line with the above-mentioned description of a circular use of the hermeneutical perspective, Osmer (2008:11) uses the concept of the hermeneutical spiral to clarify the relationship between four tasks of practical theology. These tasks are: 1) Exploration (descriptive and empirical) of the context/situation, 2) interpretation, 3) explaining and understanding (normative), and 4) pragmatic (finding ways to address the context/ situation). The author stresses that although the four tasks are distinct, they are also connected, and therefore portray a process of transformation. When working from this perspective one must constantly move between tasks, which leads to an interpretive spiral. The author continues to place specific emphasis on the fact that hermeneutics is not neutral and objective, but that pre-understanding based on past experiences is key to the interpretive spiral. Cole and Avison (2007:823) support this description and advise that Gadamer' s (1975) five-stage depiction of a hermeneutical experience be considered when working from this perspective. These stages are: (a) pre-understanding, (b) being brought up short, (c) dialogical interplay, (d) fusion of horizons and (e) application. Cole and Avison (2007:824) integrated these stages into a practical process by highlighting the need to move between the following three stages, each consisting of a specific task:

• Understanding (prejudice, reflection and conversation);

• Explanation (reflection, reconstruction and conversation) and

• Interpretation (conversation and fusion).

The decision to choose the three stages as described by Cole and Avison (2007) was based on the focus of this present contribution, namely, the development of awareness (i.e. understanding and explaining) and tolerance (i.e. new interpretation).

Considering the tasks and stages described above, the authors aimed not only to find a theoretical framework for the injustices that result from intercultural intolerance, but also to assist communities to find meaning through a process of positive change. The argument was that a lack of awareness of oneself and of others (in terms of beliefs and behaviour) leads to intolerance. In this regard, and also related to the hermeneutical spiral proposed by Osmer (2008:11) Thesnaar (2012:4) argues that one should not work from a limited perspective that seeks only solutions or ' quick fixes' . The author proposes the hermeneutical spiral as a process of transformation. This framework, as explained by the hermeneutical spiral focuses on the development of understanding and interpretation of human problems. Based on this description, the hermeneutical spiral is viewed as a perspective from which one could discover a practical way to "...actively transform and reconstruct the society we live in. To achieve this, the hermeneutical cycle needs to focus on being contextual, eco-systemic and intercultural" (Thesnaar, 2012:2).

The work done by the Institute for the Healing of Memories (2004) with a focus on healing and reconciliation (including awareness, tolerance and transformation) is a practical example of addressing this mammoth task from an intercultural hermeneutical perspective by providing a space for the different groups to journey together. This is explained in the following steps:

• Reconciliation should be viewed as a process, which could start with a workshop in a safe place where victims and offenders can engage in an effort to start the journey of reconciliation and healing.

• The process is both an individual and a collective experience with the emphasis on emotional, psychological and spiritual levels of functioning. It is advised that participants on this journey need enough time to deal with harmful memories that impact on their functioning. The aim is to deal effectively with the memories, so as to prevent the negative part of their histories from repeating (i.e. breaking the cycle).

• Activities include individual reflection, creative exercises and opportunities to share in small groups. Participants are encouraged to find 'common ground' related to shared feelings about the past.

• The workshop, serving as a first step of the journey, should be closed with a celebration that provides the platform to develop hope for the future.

For the purpose of this contribution the above-mentioned description was related to the description given by Koelsch (2012:190) on the social functions of music (as one of the arts). According to this author, in the helping professions music is based on activities that enhance awareness and tolerance as follows:

• When individuals make music, they come into contact with each other.

• Music automatically engages social cognition. When listening to music, individuals automatically engage in efforts to figure out the intentions, desires and beliefs of the individuals who actually created the music.

• Music-making can engage co-pathy in the sense that inter-individual emotional states become more homogeneous, thus decreasing conflict and promoting cohesion of a group.

• Music always involves communication.

• Music-making also involves co-ordination of actions. This requires individuals to synchronise to a beat, and to keep a beat. The co-ordination of movements in a group of individuals appears to be associated with shared pleasure.

• A convincing musical performance by multiple players is only possible if it also involves co-operation between players. Co-operation implies a shared goal, and engaging in co-operative behaviour is an important potential source of pleasure.

• As an effect, music leads to increased social cohesion of a group.

The social functions above relate to the hermeneutical process in that it involves a give-and-take process through presenting the self through music and through listening to the musical stories of others. This requires an understanding of oneself and is aimed at moving from prejudice to understanding and communication. For successful understanding, communication and reflection to take place, emotional learning is facilitated through portraying and receiving images by means of musical elements and activities. Reflection should lead to the ability to explain and reconstruct, and result in further communication that would contribute to interpretation and fusion. Musical activities are therefore followed by a joint reflection to understand and interpret. Lastly, in an effort to attain a higher level of mutual cultural acceptance, a mutual musical experience is facilitated (Kinnunen & Kaminski, 2003:7-10).

By using the theoretical description of Cole and Avison (2007) as a hermeneutical lens, the link was made between theory and practice and is illustrated in the table below.

The table above provides a description of the relevance of working from an intercultural hermeneutical perspective. In terms of the hermeneutical spiral, as well as the practical examples above, the authors of this contribution were interested in understanding and interpreting how human beings discover meaning in relation to their own and other's cultural identity and intercultural relations. Human action/behaviour is a form of expression as it represents meanings and thoughts related to specific experiences and contexts (Greuel & Van der Westhuizen, 2013:2-6). In this regard, Grondin (1994:21-22) refers to Dilthey's description of hermeneutics. Dilthey argued that experience means that one feels a specific situation personally, and that one can begin to attach meaning once the experience is explored. Expression then converts experience into meaning by means of verbal and/or non-verbal sharing with others. In this regard, Dilthey specifically referred to misunderstanding; meaning that the way we express ourselves may not be interpreted by others as we intended. The relevance to this contribution is that a lack of personal awareness, combined with misinterpretation and misunderstanding by others, could lead to intolerance that influences inter-relations.

The eco-systems approach supports the hermeneutical perspective of finding a practical application (i.e. a way of dealing with a situation) that could lead to intercultural awareness and tolerance. This approach is embedded within the hermeneutical cycle of understanding and interpreting, and could be viewed as an approach guided by the examples provided above (Institute of the Healings of Memories, 2004; Koelsch, 2012). With specific reference to the context in which people function, the eco-systems approach, for the purpose of this contribution, implies that different cultural groups within a community affect one another's functioning - the meaning they attach to certain contexts, as well as the well-being of the community as a whole. According to this approach, those aspects (e.g. cultural practices, language and beliefs) that explain the reciprocal relationships between individuals, groups and/or communities should be included when attempting to develop a positive-change environment. It is aimed at the promotion of social functioning, addressing environmental impacts and developing problem-solving skills. This aspect also addresses the issue of responsibility discussed in the previous section, as it enables civic society to become active seekers of solutions to problems. Problems are solved through the technique of ' systems thinking,' where problems are approached in such a manner as to assist the different parts to contribute to a ' better whole' . The aim is to create a different way of thinking/perceiving (through an exploration of meaning) that would lead to constructive behaviour (i.e. forms of expression) to contribute to long-term change. The approach uses a cyclical rather than linear cause and effect view (Lars, 2006:36). Therefore, problems are solved through a process (see description of the hermeneutical process), where changes in different systems influence the changes that take place in the whole context (Timberlake, Zajicek-Faber & Sabatino, 2008:5; Ackoff, 2010:12). In terms of this contribution, it refers to addressing intercultural intolerance by mobilising different cultural groups towards an awareness of their own and foreign cultural identities, thereby influencing the meaning they attach to certain contexts, that will create the space towards positive change.

To be able to work from an eco-systems approach and to implement systems thinking, the term ' system' should be understood. A system (for example, a multicultural community) can be described as an entity with a specific purpose and consisting of various interrelated or interdependent factors, such as activities and interactions. Ackoff (2010:13) describes the term 'interpretive systems' as a form of systems thinking that models 'reality' based on differing views of the individuals, groups and communities associated with the system (i.e. a multicultural community). The meaning and interpretations regarding a specific context, as perceived by a variety of interrelated sources, provides us with ". emergent processes addressing system contradictions and participant expectations". The theologian Augsburger (1986:178) defines a systemic approach as an inclusive process of relationships and interactions. He further explains that a system is a structure in process; in other words, a pattern of elements undergoing patterned events. The human person is a set of elements undergoing multiple processes in cyclical patterns as a coherent system. Thus, a system is a structure of elements related by various processes that are all interrelated and interdependent. Added to this, Louw (1998:74) refers to Friedman's (1985:14-15) definition of a systems approach as follows: "...A (He) draws attention to the fact that a systems approach focuses less on the content and more on the processes: less on the cause-and-effect connections that link bits of information and more on the principles of organisation that give data meanings." In this regard, systemic thinking within the pastoral encounter does not only take note of the person and psychic composition, but notices especially the position held by a person within a relationship.

Both the hermeneutical perspective and the eco-systems approach place the emphasis on the meanings individuals, groups and communities attach to certain contexts/situations and the inter-relations that could be the focus of a process of moving towards awareness and tolerance.

In a multicultural context, and when working from this theoretical framework, the professional helper assists groups to mobilise the strengths of their relationships to address social, mental and spiritual well-being (Stratton, 2010:5). Moreover, the eco-systems approach acknowledges the importance of the environment in which people function, including cultural practices. The challenge for professional helpers is to find a practical way to examine relevant societal issues critically so as to create a better understanding of societal contexts and needs (White & McCormack, 2006:122).

Conclusive Recommendations

This contribution aimed to contribute to the on-going process of journeying towards intercultural awareness and tolerance within the South African society. It specifically argued that government and civil society should take co-responsibility to work towards this goal. It is recommended that a responsible way to engage in this journey is by means of a trans-disciplinary process, therefore, including all possible helping professions, e.g. the disciplines of social services, theology and the arts.

With this background, the first section of this article focused on the value of a trans-disciplinary conversation. The second section built on the trans-disciplinary dialogue in an effort to find a theoretical framework from which to approach intercultural awareness and tolerance. This section provided descriptions related to the on-going lack of awareness between the different groups in post-Apartheid South Africa; intercultural intolerance; awareness of one' s own, as well as other culture; the need for collective responsibility; a shift towards an intercultural hermeneutical perspective when working in multicultural communities and using intercultural practices; and the universal human need for betterment. This assisted the authors to describe how the eco-systems approach could be utilised when working from an intercultural hermeneutical perspective to engage in a journey towards intercultural awareness and tolerance. It is envisaged that the recommendations could lead to a further exploration of the practical implementation of the recommended theoretical framework.

The use of the eco-systems approach towards intercultural awareness and tolerance should be utilised within the hermeneutical spiral as a perspective and a guiding process. Within this framework, it is recommended that further exploration regarding ' how' to develop pragmatic guidelines for implementation should take place. The authors, using the proposed theoretical framework and the hermeneutical process described by Cole and Avison (2007:824), as well as guidelines given by the Institute of the Healings of Memories (2004) and Koelsch (2012), also recommend that such practical guidelines should focus on:

• Exploring all the relevant components of a specific context to develop an understanding of the self and others,

- Exploration (descriptive and empirical) of the context/situation,

• Identifying techniques to assist individuals, groups and communities to interpret the relevant components,

- Moving from prejudice to understanding through conversation, interpretation and reflection,

• Identifying techniques to become able to explain and understand situations,

- Explaining and understanding (normative) and reconstruction through ongoing conversation,

• Developing the ability to find ways to heal (a movement towards happiness and satisfaction) and

- Pragmatic (finding ways to address the context/situation): Further conversation that encourages interpretation and that leads to fusion (i.e. integration and healing).

It is envisaged that the above-mentioned recommended focus areas for further investigation could make a valuable contribution to provide professional helpers with a practical framework from which to work to encourage intercultural awareness and tolerance.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackoff, RL 2010. Systems Thinking for Curious Managers. Triarchy Press, Devon. [ Links ]

Anderson, JR 2005. Cognitive Psychology and its Implications, 6th edition. WH Freeman and Company, New York. [ Links ]

Audi, R 1999. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Augsburger, D 1986. Pastoral Counselling across Cultures. Westminster, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Bosch, DJ 1991. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. Orbis Books, New York. [ Links ]

Branscombe, NR & Wann, DL 1994. 'Collective self-esteem Consequences of Out-group Derogation when a valued social Identity is on trial. ' European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 24:641-657. [ Links ]

Buccus, I 2013. Political Tolerance on the Wane in South Africa. University of KwaZulu Natal, School of Politics, Durban. [ Links ]

Cohen, GL & Garcia, J 2005. 'I am Us: Negative Stereotypes as Collective Threats.' Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4):566-582. [ Links ]

Cole, M & Avison D 2007. 'The Potential of Hermeneutics in Information Systems Research.' European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 16:820-833. [ Links ]

Danesh, HB 2011. Human needs Theory, Conflict and Peace: In Search of an integrated Model. Viewed 13 June 2014, from Academia Edu Online Journal. http://www.academia.edu/6985348/Human_Needs_Theory_Conflict_and_Peace.

Du Preez, GT 2000. 'Teaching Homiletics in a multi-cultural Context: A South African Perspective.' Paper delivered at the 27th International Faith Seminar in Thailand, 2-15 December 2000, Institute for Christian Teaching, Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring. [ Links ]

European Commission, 2014. European Agenda for Culture. European Commission: Directorate General for Education and Culture, Brussels. [ Links ]

George, J 2012. Intercultural Theology: An Approach to Theologizing in the Context of Pluralism and Globalization. Unpublished Master of Theology Degree Thesis, Toronto School of Theology, Toronto. [ Links ]

Gibson, JL & Gouws, A 2005. Overcoming Intolerance in South Africa: Experiments in Democratic Persuasion. Cambridge University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Greuel, T & Van der Westhuizen, MA 2013. Music in the Fields of Social Work: An Introduction. Evangelische Fachhochschule Rheinland Westfalen Lippen (Bochum, Germany) and Huguenot College (Wellington, South Africa). [ Links ]

Grondin, J 1994. Introduction to Philosophical Hermeneutics. Yale University Press, New Haven. [ Links ]

Hertnon, S 2005. Theory of Universal Human Needs. Viewed 24 November 2012, from http://www.nakedize.com/universal-human-needs.cfm#article.

Hope, A & Timmel, S 2003. Training for Transformation: A Handbook for Community Workers. Book 4. ITDG Publishers, London. [ Links ]

Institute for Healing of Memories, 2004. 'Journey to healing and wholeness.' Robben Island Conference report, IHM, Cape Town, Claremont. [ Links ]

Kinnunen, K & Kaminski, W 2003. Enhancing Cultural Awareness through Cultural Production. Kauniainen Unit of Humanities Polytechnic and the Korpilahti Unit of Humanities Polytechnic & University of Applied Sciences, Cologne.

Koelsch, S 2012. Brain and Music. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex. [ Links ]

Lars, S 2006. General Systems Theory: Problems, Perspective, Practice, 2nd edition. World Scientific Publishing Company, London. [ Links ]

Lefko-Everett, K 2012. South African Reconciliation Barometer: Ticking Time Bomb or Demographic Dividend? Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Leiner, M & Fläming, S (ed.) 2012. Latin America between Conflict and Reconciliation. Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Louw, DJ 1998. A Pastoral Hermeneutics of Care and Encounter. Lux Verbi, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Louw, DJ 2008. Cura Vitae, Lux Verbi, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Mbu, J 2014. 'The Story of Pretoria Faith Community and PEN creating Space for the Foreigner'. Paper delivered at the Forum for Intercultural Ministries, February 2014. Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mittelstraß, J 2005. "Methodische Transdisziplinarität", Technikfolgenabschätzung.' Theorie und Praxis, Vol. 14(2):18-23. [ Links ]

Motloung, B 2013. Cultural Tolerance and the South African Experience. South African Embassy in Bulgaria, Sofia. [ Links ]

Ojambo, MAN 2009. Exploring Political Intolerance in South Africa. Unpublished Honours Thesis, Department of Psychology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Osmer, RR 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction. William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Portera, A 2008. Intercultural Education in Europe: Epistemological and Semantic Aspects. Intercultural Education, Vol. 19(6):481-491. [ Links ]

Ramberg, B & Gjesdal, K 2005. 'Hermeneutics'. Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy.' Viewed 1 January 2013, from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hermeneutics/. [ Links ]

Renfro, CL, Duran, A, Stephan, WG & Clason, DL 2006. 'The Role of Threat in Attitudes toward Affirmative Action and its Beneficiaries.' Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 36:41-74. [ Links ]

Riek, BM, Mania, EW & Gaertner, SL 2006. 'Intergroup Threat and out-group Attitudes: A meta-analytic Review.' Personality and Social Psychology review, Vol. 10:336-353. [ Links ]

Schokel, LA & Bravo, J 1998. A Manual of Hermeneutics (Biblical Seminar). Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Shklar, JN 2004. 'Squaring the Hermeneutic Circle.' Social Research, Vol. 71(3):657-658. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa, 2013. Statistical Release: Mid-year Population Estimates. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Stephan, WG, Ybarra, O & Bachman, G 1999. 'Prejudice towards Immigrants.' Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 29:2221-2237. [ Links ]

Steyn, M 2011. Being different together: Case Studies on Diversity Interventions in some South African Organisations. University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Stratton, P 2010. The Evidence Base of Systemic Family and Couples Therapy. Association for Family Therapy, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Tavallaei, M & Mansor, AT 2010. 'A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research' . Journal of International Social Research, Vol. 3(11):570-577. [ Links ]

Taylor, C 1985/ 'Interpretation and the Sciences of Man.' Philosophy and the Human Sciences, Philosophical Papers, Vol. 2:15-57. [ Links ]

Thesnaar, CH 2012. 'A Pastoral Hermeneutical Approach to Reconciliation and Healing: A South African Perspective.' In M Leiner & S Fläming (ed.), Latin America between Conflict and Reconciliation, Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 215-229. [ Links ]

Timberlake, EM, Zajicek-Faber, M & Sabatino, CA 2008. Generalist Social Work Practice. A Strengths-based problem-solving Approach. Allyn and Bacon Publishers, Boston. [ Links ]

Tropman, JE, Erlich, JL & Rothman, J 2008. Tactics and Techniques of Community Intervention, 7th edition. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont California. [ Links ]

United Church of Canada, 2011. Defining Multicultural, Cross-cultural, and Intercultural. The United Church of Canada/L'É [ Links ]glise Unie du Canada.

Van der Westhuizen, MA & Kleintjes, L 2015. Social Work Services to Victims of Xenophobia. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, Vol. 51(1):115-134. [ Links ]

Williams, L 2002. It' s the little Things: Everyday Interactions that anger, annoy, and divide the Races. Harcourt Publishing, New York. [ Links ]

White, C & McCormack, S 2006. 'The Message in the Music: Popular Culture and Teaching in Social Studies.' The Social Studies, Vol. 97(3):122-127. [ Links ]

Whitesel, B 2013. The Healthy Church: Practical Ways to Strengthen a Church's Heart. Wesleyan Publishing House, Fishers IN. [ Links ]

Zhang, X 2011. 'On Interpreters' intercultural Awareness.' World Journal of English Language, Vol. 1(1):47-52. [ Links ]

1 See the article by Jürgen Mittelstraß, (2005:18-23) in this regard.

2 See the article by Jürgen Mittelstraß, (2005:18-23) in this regard.