Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scriptura

versão On-line ISSN 2305-445X

versão impressa ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.114 Stellenbosch 2015

ARTICLES

Living in three worlds: A relational hermeneutic for the development of a contextual practical theological approach towards a missional ecclesiology

Guillaume Hermanus Smit

Department of Old and New Testament Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

This article argues for an integrated paradigmatic approach to conducting practical theological research. This integration is prompted by the researcher's experience as theologian in a culturally diverse community where theologies from different perspectives share the same ecclesial landscape. Three primary thought paradigms are discussed as a frame of reference for this integration. These are the pre-modern paradigm, the modern paradigm and the postmodern paradigm. A relational hermeneutic is proposed that utilises the story of Scripture as told through the centuries and strives to share God's mission to the world. This relational hermeneutic could serve as the integrational focal point of ministry practice that spans theological viewpoints.

Key words: Relational Hermeneutic; Theological Paradigms; Missional Ecclesiology; Paradigm Theory; Trinity

Introduction

For several centuries society at large held a certain worldview that accepted the dominance of the Christian religion as well as Western civilisation (Keifert 2006:24). Since it is rather obvious that this time has passed - and new paradigms that encompass previous world views have arrived with a historical impact similar to 'high tectonic activity' (McLaren 2000:12) - it may present itself as redundant to revisit a discussion about worldviews and paradigms that has been set aside already. Yet, the opportunity for developing a new missional paradigm is arising. It may very well be an opportunity that will help to facilitate new ecclesiological practices for congregations engaging in this missional paradigm. Keifert described this shift as a time where the ideas of the Enlightenment are criticised as mostly European and intentionally connected with new reflection on the methods and ideals of pre-modern cultures from other parts of the world as well as from pre-modern Europe (Keifert 2006:20). Within the discussion of an emerging missional ecclesiology there is a place, therefore, to revisit three of the dominant cultural paradigms within which the church is participating in God's mission.

In exploring this, the term mission needs to be understood as a reference to the missio Dei, to God's self-revelation as the one who loves the world, God's involvement in and with the world, the nature and activity of God in which the church is privileged to participate (Bosch 1991:10). The term missional is used as a technical adjective denoting something that is related to or characterised by mission (Wright 2006:24). Ecclesiology should be understood as a hermeneutical theological theory, based on the testimony of Scripture, upon which the church develops and builds its operational practices (Smit 2008:162). Missional ecclesiology, then, is the area of theological study that explores the nature of Christian movements, and therefore the church, as they are shaped by Jesus and his mission (Hirsch 2006:285).

Niemandt (2012:1-2) investigated several factors precipitating the increasing interest in a new missional ecclesiology paradigm and, as a result, identified the following contours of such an ecclesiology:

- Participation in the life of the Trinity

- Joining in with the Spirit

- Ecclesiology follows mission

- Incarnational, or universal and contextual

- Relational

- The Kingdom of God

- Discernment as the first act of mission

- Creativity

- Local community

- Ethics and mission

Since God's mission is revealed through Scripture, missional ecclesiology is also a her-meneutic venture. The practice of reading the Bible theologically is construed in a way to shape human praxis (Green, 1995:412) resulting in the formation and nurture of Christian communities (Fowler 1995:408). This implies that a missional ecclesiology will comprise an understanding of God's salvific activity in contemporary history, and a specific focus on the role and practices the church in its local embodiment as congregation exerts as resulting response to this ongoing labour of God, placing the discussion in the overlap between practical theological and missiological inquiry. The manner in which Christians engage the world with their testimony about God's work depends greatly on the paradigm from which they read Scripture, or the way they 'let Scripture be Scripture' (Wright 2009:40), and apply these insights to their specific cultural interpretation (McKnight 2008:13). It affects ecclesiological practices and it dictates missional approaches. It also stems from the paradigmatic lens through which they engage in Scripture reading.

Methodological Considerations

For the purpose of this investigation we will concentrate on three overarching paradigms, all sharing common denominators that will be presented with the somewhat broad strokes of an inquisitive pen. For the purpose of this discussion the hypothesis could be stated as follows: The integration of aspects of pre-modern, modern and postmodern theological paradigms through a relational hermeneutic is beneficial to the development of a Practical Theological perspective on an emerging missional ecclesiology.

Since this discussion centres on different paradigms, it only makes sense that as researcher, I declare my own paradigmatic presuppositions. I am writing from a Dutch Reformed perspective, as an Afrikaans theologian, who specialised in Practical Theological and New Testament Sciences at postgraduate level. I am serving a predominantly white, Afrikaans and middle class suburban congregation as pastor. My theological thoughts are therefore shaped by Western theology in an African context while my congregational experiences come from a church community that is struggling with its calling as a missional church.

A last remark can be made about methodology. Since the hypothesis stated an explicit interest in missional ecclesiology, the process used to reach a conclusion to test it stems from the core tasks of practical theological inquiry (Osmer 2008:4). Some emphasis will be placed on the descriptive-empirical task since we are trying to discern the patterns and dynamics of the way people in the three paradigms under investigation are applying their specific reading of Scripture to missional ecclesiology. Yet our research proposal begs similar attention to the normative and pragmatic tasks of Practical Theology inquiry. To facilitate this, a relational hermeneutic that may bridge the dividing chasms between the paradigms is proposed as way of interpreting Scripture, which forms part of the normative task of Practical Theology. After all, Practical Theology has been described as "the theory of the facilitating of the Christian faith in modern society", providing its purpose as one of guiding and influencing society towards change (Heitink 1993:195). Through this, new insight may be gained in the contours of missional ecclesiology as ongoing discussion on the identity of being a church of Christ. Finding insight in the church's missional identity enables it to start answering the questions pertaining to the reasons of its existence, its deepest loyalties and relationships (Burger, 1999:53).

Brief Perspectives on the Nature of Paradigms

A paradigm can be described as a scale model of a huge, complex or incomprehensible state of affairs, providing a road map to reality in the quest for better understanding of complex issues (Smit 1997:9). A paradigm nearly always has a fixed set of rules that defines boundaries and establishes guidelines for success (Barker 1985:14).

The term 'Paradigm Shift' was originally coined by Thomas Kuhn who likened the scientific embrace of a new paradigm to a person wearing inverted lenses, finding the same constellation of objects thoroughly transformed in many of their details (Kuhn 1996:122). Kuhn's thesis can be summarised as follows: Within a given scientific field its practitioners hold a common set of beliefs and assumptions, agree on the problems that need to be solved and the rules that govern their research and standards by which performance is to be measured. Paradigms, however, aren't necessarily unchangeable. When several of a scientific discipline's practitioners start to encounter anomalies or phenomena that cannot be explained by the established model, the paradigm starts to show signs of instability (Hairston 1982:76). For some time the practitioners try to ignore these inconsistencies and contradictions or make improvised changes to counter the immediate crises. If enough anomalies accumulate to convince a substantial number of practitioners to start questioning the traditional paradigm with which they solved their problems, a few innovative thinkers devise a new model. When enough practitioners become convinced that the new paradigm works better than the old one, they will accept it as the new norm (Hairston 1982:76). According to Kuhn (1996:23) a paradigm should not only be viewed as a model or pattern that can be replicated or used as pro forma example for other instances, it can also be an object for further articulation and specification under new or more stringent conditions. A paradigm gains status because it is more successful than its competitors in solving problems that a group of practitioners have started to view as acute.

Even though Kuhn explicitly wrote from a natural sciences perspective, his thoughts regarding the formation and transformation of scientific paradigms have obtained wider recognition as being applicable also to the way social scientific inquiry can be conducted (Bird 2011). Some practical theologians, such as Heitink (1993:124-127) successfully traced a link between the social sciences and Practical Theology - therefore we can cautiously attempt to utilise Kuhn's theses on paradigm shifts as a framework for this discussion. It has also been appropriated for theological consideration, albeit with some caution and limitations, as a working hypothesis, by Bosch (1991:184) since Kuhn's research succeeded in making explicit, ideas regarding scientific research what had previously been accepted on an implicit level only.

For the purpose of this discussion, the existence of the three overarching theological paradigms can be placed as a continuum of views that share the common denominator of Biblical Scripture as foundational reference point:

Cursory Remarks on the Pre-modern Paradigm

Pre-modern Theology has its origins in the church culture of the time between the New Testament writings and the sixteenth century of this Common Era. The first part of this time was dominated by the so-called apostolic paradigm, which distinguished itself from later pre-modern theology by virtue of its position in society. Later pre-modern theology formed part of another paradigm that can be called the Christendom Paradigm.

' Apostolic Paradigm' refers primarily to the ecclesiological understanding of faith communities in the time of the apostles and directly thereafter. The church's existence in the Apostolic Paradigm was a tumultuous time (Mead 1991:9). Jesus' call to serve and convert the world, care for the sick, the prisoner and the widow, the fatherless and the poor resulted in the development of different styles and structures (Mead 1991:10). Collegial and monarchical structures co-existed and communal experiments held sway in different places. Different functions and roles emerged. Some churches fought to retain links with their Jewish roots while others distanced themselves from that community. From this, the Apostolic Paradigm emerged. The early church was aware of itself as a religious community surrounded by a hostile environment to which each witness was called to witness God's love in Christ. They viewed themselves as bearers of the euanggelion, the Greek word used to denote evangelism.

Green (1984:59) argued that euanggelion was frequently used in this time as description for the good news about the Kingdom of God that was being personified in Jesus. Incidentally, euanggelion can also be translated in a more contemporary idiom as 'breaking story' or 'headline news' (Martoia 2007:8). At the centre of this task, the local church functioned. It was a community that lived by the power and values of Jesus (Mead 1991:10). These were preserved and shared within the intimate community through apostolic teaching and preaching, the fellowship of believers and ritual acts such as the breaking of bread and wine in the Eucharist. People only gained entrance into the community when the members of the community were convinced that the newcomers were in agreement with those values and were born into that power.

Kreider (1999:23) shows how these early churches attempted to nurture communities whose values would be different from those of conventional society. It was assumed that people would live their way into a new kind of thinking. Thus, the socialisation, professions and life commitments of candidates for church membership would determine whether they could receive what the Christian community considered to be good news.

The local church was an intense and personal community. To belong to it was an experience of being in immediate touch with God's Spirit. This was, however, not a utopian community. The New Testament epistles frequently describe schisms and conflict between church members. To the other side was the hostile environment that was opposed to the church community. Each group of Christians was an illicit community and in many places, it was a capital offense to be associated with or to be a Christian (Mead 1991:10-11).

The second aspect of the Apostolic Paradigm was the commission built into the story that formed the church (Mead 1991:12). They understood their calling as one of reaching out to the environment, going into the world and not being of the world, engaging the world. The local churches saw its front doors as the frontier into mission. They called it witnessing and this shaped their community life. The difference between life inside the community and outside it was so great that entry from the world outside was a dramatic and powerful event, symbolised by baptism as a new birth.

The community's leaders were involved in teaching and preaching the story and recreating the community in the act of thanksgiving as symbol of a new life in a new world. These new perspectives and possibilities were expressed in a symbolic and social language that was familiar and addressed people's questions and struggles (Kreider 1999:15). Congregation members had roles that fit their mission to the world - servant-ministers who carried food to the hungry and healers who cared for the sick.

The local churches also perceived their mission to be the building up of its members with the courage, strength and skills to communicate the good news from God within that hostile world. Internally, it ordered its communal life, and established roles and relationships to nurture the members of the congregation in the mission that involved every member. The perception of the members was that they received their power to engage in this mission from the Holy Spirit (Mead 1991:12-13).

The Christendom Paradigm, where the church occupied a central position within Western societies, ranged from the conversion of Emperor Constantine in 313 CE to roughly the midpoint of the twentieth century (Gibbs & Bolger 2005:17). The conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine in 313 CE changed the status of the Christian faith radically and introduced the Christendom Paradigm. Before this, paganism dominated the Roman Empire (Viola & Barna 2008:6). Within seventy years the status of Christianity changed from persecuted faith to legitimate faith and finally to state religion (De Jongh 1987:55). As a result, drastic changes took place in the Christian culture:

- In 321 CE the first day of the week was declared an official day of rest, although the name was kept to reflect the pagan heritage (Sunday);

- In 380 CE, Emperors Gratian and Theodosius declared all subjects of the Roman Emperor to adhere to the faith as confessed by the bishops of Rome and Alexandria.

- Since 392 CE it was illegal to conduct any private services of non-Christian religions (De Jongh 1987:56).

- By 592 CE an edict of Emperor Justinian made conversion - including the baptism of infants - compulsory for any member of the Roman Empire (Kreider 1999:39).

The difference between this Christendom Paradigm and the Apostolic Paradigm was that by law the church was now identified with the empire (Mead 1991:14): Everything in the world that immediately surrounded the church was legally identified with the church without any separation. The hostility from the environment was removed by making church and environment identical. Thus, instead of the congregation being a small local group that made up the church it became an encompassing entity that included everyone living in the Empire. Suddenly there was no boundary between church and the local community. The missionary frontier disappeared from the congregation's doorstep to become the political boundary of society itself, far away.

The pre-modern culture in which the church functioned, found its philosophical foundations particularly in the dialogues of Plato and the works of Aristotle (Drilling 2006:3 ff). The underlying assumption of the pre-modern culture is that all reality is hierarchically ordered, beginning with God, who governs the realm of being. Thus, the laws of nature, humanly created society, and the mind that thinks, know that all these run parallel to each other and participate in an orderly cosmos that is directed in some way by the divine.

Because of the influential position of the church, Christian thinkers succeeded in changing Plato's view of the eternity of matter into the Genesis-based belief that God created everything from nothing. Through exerting this Scripture-based influence on rational thinking, the onto-theological perspective of reality was extended to recognising -even preconditioning - the rule of God in every dimension of nature, human and otherwise. Drilling (2006:3-4) shows, among others, the following implications of this development: The foundations of Christian interpretation of moral law were laid through the interpretation of the Decalogue into natural law and divine positive law and human law, along with the meaning and role of conscience; and Church structures were established and defined the role of the ordained and the place of the baptised - the laity - along with the civil jurisdiction of the diocese and parish.

Eventually Thomas Aquinas explicitly developed the idea that all things created come forth from God and are ordered toward a return to God (Drilling 2006:4). This resulted in Aquinas' famed two-step thinking process - an inquirer seeks first to grasp the inner essence or form of a subject by an act of understanding. To achieve this, the five senses are used. Secondly, the inquirer seeks to affirm or deny the actuality of objects of which the essence or form has been grasped by an act of understanding. Everything that falls outside this scope is then rejected as imaginary as it doesn't fit into the objective order of being in its truth and goodness. Aquinas thus formulated a correspondence theory of knowledge: what one truly knows corresponds with what actually exists and the mind is able to affirm that (Drilling 2006:4-5).

Mead (1991:14-22) attempted to describe the ecclesiological implications of this paradigm shift into pre-modern Christendom. First of all, congregation members were no longer personally engaged on the mission frontier. They were no longer called to witness in a hostile environment or supposed to be different from other people - as citizenship became identical with one's religious responsibility, the logical thing to do. Secondly, the missional responsibility became the job of a ' professional' on the edge of the Empire - the soldier or the missionary. Therefore, winning souls for God and expanding the Empire by conquest became the same thing. It was expected of a Christian to be a good citizen and support state and church in subduing and converting the pagan outside the borders of the Empire (Mead 1991:14).

Revisiting the Modern Paradigm

The move from a pre-modern to a modern culture was precipitated by two factors (Drilling 2006:5): First, as a result of the emergence of humanism, a new acceptance of human creativity developed as it was discovered that the human imagination had always been part of being human. This led to the development of new modes of human expression, such as artistic, political, and philosophical and the Renaissance began. Second, the Thomist synthesis was taken apart by nominalist theology which was sceptical towards the inherent meaningfulness of things. The dominant view became that God can do as God wills, therefore reality is only what God decides to make. Names don't denote the inner meaning of things, but are mere terms that humans impose on things to distinguish them from other things based on their differences - hence nominalism. Modernism has been described as the social development characterised by the intention to solve problems from the perspective of rationality (Van der Ven, 1993:18).

The full advent of modern culture was specifically catalysed by two events (Drilling 2006:6). The first was the scientific revolution in the seventeenth centur, when the experimental method became the vehicle of a remarkable new moment in human creativity. The second event was the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. The experimental method became an agenda for all dimensions of life and human beings were challenged to take charge of life for themselves. These led to structural individualism of all aspects of society (Heitink, 1993:46). Control that had once been in the hands of civil and religious authorities was wrested away. People increasingly displayed greater individuality and autonomy and felt more and more adept at determining their own destinies. Individual freedom and autonomy became the order of the day.

The Modern Culture was philosophically undergirded by the musings of Descartes and Kant and the idea that the mind must activate a procedure of doubt with the aim to reach absolutely certain truths, was born. This fitted neatly in the methods of the new natural sciences which tried to assume nothing - a sort of doubt (Drilling 2006:7). The new natural sciences sought to be precise about the inner workings of objects of research by means of carefully constructed empirical experiments conducted upon particular elements comprising the research matter. This was a move away from the deductive method to the inductive method. Drilling (2006:7) shows that this rationalism and the idealism of Kant succeeded in creating a dark downside, namely the breakdown of all sense of common truths and values, and the consequent fragmentation of human social order.

Modernity succeeded positively in discovering the central role of the human subject in every instance of knowledge (Drilling 2006:8). This opened the way to the grounding of faith that was lacking in the pre-modern period. However, as modernism failed to work out the turn to the subject in several of its expressions; religious faith - faith based on revelation - was banished from socially acceptable discourse of the important issues of the day. Modernity's willingness to consider religion was clouded by its only concern with a God of reason and natural religion, thus subjecting it as subject of research, criticism and protest (Van der Ven, 1993:29).

The Rise of the Postmodern Paradigm

The 'classic proof texts' used by way of pre-modern application to carry the impetus of the modernistic view of mission, "executing the Lord's command to preach the gospel to the whole creation" (Morrison, 1910) - texts such as Matt 28:18-20, Acts 1:8, etc - have long been used as biblical foundation for the church's missional endeavours. It was used to mobilise countless generations of young people to enter into full-time mission work in foreign countries. It reflected in research on mission theology and it undergirded the Western, modernistic understanding of the church's missional responsibility (Bosch 1991:4-5), which, in the words of Gustav Warneck, could be seen as this: Mission is founded on Scripture, the Christian religion is absolutely superior to other faiths, the Christian faith is adaptable to all cultures, and this all is proved by the superior achievements of missionaries in the mission fields. Contemporary culture has excelled, however, in becoming an oxymoronic society of and/also, instead of either/or (Sweet 1999:370), making the development of theological theories on mission no longer isolated scientific exercises set in dogmatism, but an ongoing process of reflection that incorporates contradictions and even doubt with strengthening ease. It intentionally allows insights from other disciplines and paradigms to enhance its scope. This produces a paradigm shift to double reflexivity: researchers are reflecting on their own field of expertise and their perspectives as a form of scholarship, yet they are also reflecting on the contribution of their research on the interlocking natural and social systems in which life is lived (Osmer 2008:240). And it succeeded in making the above-mentioned understanding of mission untenable.

This paradigm shift grew epistemologically from the philosophical-literary herme-neutics of Paul Ricoeur, Jean-Francois Lyotard and Jacques Derrida. According to Ricoeur (1991:165) language, as symbolic system, can provide meaning to social occurrences. As such structural analysis can help other sciences such as theology to achieve deeper interpretations of a given situation. According to Lyotard (1984:1), "scientific knowledge is a kind of discourse. And it is fair to say that for the last forty years the 'leading' sciences and technologies have had to do with language: phonology and theories of linguistics, problems of communication and cybernetics, modern theories of algebra and informatics, computers and their languages, problems of translation and the search for areas of compatibility among computer languages, problems of information storage and data banks, telematics and the perfection of intelligent terminals, to paradoxology. " Knowledge ceased to be an end in itself. Language became creator of meaning, albeit a pragmatic one. Subsequently, Lyotard announced the fall of grand meta-narratives based on universal, transcendent truths (Lyotard 1984:37-38).

Derrida, one of the fathers of deconstructionist literary theory, had elaborated a theory of deconstruction of discourse that challenged the idea of a frozen structure and advanced the notion that there was no structure or centre, no univocal meaning. The concept of a direct relationship between signifier and signified was no longer tenable, and instead we had infinite shifts in meaning relayed from one signifier to another (Guillemette & Cossette 2006). Through Derrida's deconstruction, it was possible for theological discourse to break free from modernist constraints of over-analysing God and religion to discover the wholly other and, taking language by surprise, will tie our tongue and strike us almost dumb, while filling us with passion (Caputo, 1997:3).

Technologically, the paradigm shift has been carried by developments in the fields of communication, digital technology and social networking. The impact of these developments is tremendous: It has changed the way people conduct business and go about their work, it affects relationships and relational networks between people, it changes the way people gather, process and utilise information and it fundamentally transforms the way people interact with each other (Saxby 1990:3): Suddenly, information has become personal. Individuals have a large range of personal choices and opportunities for access to the distribution and reception of information. No longer are people passive receivers of information (Saxby 1990:259-299), they exhibit an increasing need for information as basis for making their decisions (Pettersson 1989:33).

The proliferation of new media technologies caused a significant shift in focus from reading and writing to watching and listening (Pettersson 1989:77-78). The result is a society in which the reigning culture, value system and norms are increasingly dictated by image rather than regulating. Even more importantly, the digital world is busy changing humanity's sense of time and history, since this new world pulls the future into our consciousness while simultaneously extracting the best of the past (Miller 2004:76-77).

The implications of the digital revolution can be summarised as follows (Miller 2004:78): The digital culture's need for direct, uncontrolled and first-hand experiencing is replacing the passive gestalt of television and printed media types; the dependence by the digital culture on networks and personal relationships is replacing television's bias towards collective stadium-event experiences; digital culture's open source technologies, organisations and thinking mechanisms (such as Wikipedia) have disrupted printed media and television's tendencies for trademarking; the ability of the digital culture to revisit the past is replacing television and the printed media's rejection of the past; the digital culture's paradigm-based approach to complex issues and conflict is replacing the political approach by television and printed media; the integrated, multimedia language of the digital culture is replacing television and the printed media's visual language; and finally, the digital culture's integration of left brain and right brain processes is replacing television and the printed media's sole reliance on right brain processes.

The digital revolution sweeping our era is shaping it through three interdependent processes - among others: neoliberal globalisation, the information technology revolution, and a phenomenon that arises from the combined effects of the previous two perspectives facilitating a speedier and smaller world (Hassan 2008:ix), leading to the following dynamics:

- Interconnection: We have entered a chain reaction world of exponential outcomes where problems and opportunities are intimately tied together. Networks are emerging which seem to have a collective intelligence that defy older logic and sequential decision-making processes (Miller 2004:4-5).

- Complexity: Systems do not behave as a collection of spare parts anymore, but as an integrated whole. Any single change sets in motion an invisible ripple effect and old analytical tools fail to anticipate potential consequences of policy or action within complex systems of relationships (Miller 2004:5).

- Acceleration: With each new technology or concept, change seems to be accelerating. This results in change taking on a life of its own, and people start to feel out of control from time to time (Miller 2004:5).

- Intangibility: The world is changing from a society that measures value in terms of products that can be touched or held to a society that measures value in terms of intangibles such as information, potential or reputation (Miller 2004:5).

- Convergence: This is the inherent property of the digital era. All information, be it print, graphics, sound or data, can all reside on a single medium - CD or DVD -because it is all reproduced through the common digital language of bits and bytes. Therefore, the boundaries that separated disciplines of knowledge (such as physics, poetry and metaphysics) are beginning to blur (Miller 2004:5-6).

- Immediacy: The time it takes to absorb and adjust to digitally paced activities is growing shorter and shorter. People are therefore under pressure to respond to the changes with immediacy similar to that required by fighter pilots in combat (Miller 2004:6).

- Unpredictability: In the old paradigm, physics taught that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. However, current complex and highly interactive systems are highly unpredictable. Since these systems are interconnected, the number of outcomes is exponentially multiplied, making it impossible to predict. In every instance, in complex systems its actions often create unintended and unforeseen consequences (Miller 2004:6-7).

Towards a Relational Hermeneutic

A relational hermeneutic serves as conceptual framework through which the contours of a missional ecclesiology may be further investigated and developed. The framework proposed forthwith was previously developed (Smit 2008:167-170) and is adapted and redeveloped in this discussion.

Let us attempt a short elaboration while simultaneously refraining from oversimplification. Unfortunately, the constraints placed by the format of this presentation demand a limitation; therefore we will be focusing on only three central theses of this relational hermeneutic.

- A relational hermeneutic seeks to understand missional ecclesiology from the perspective of the Triune God

The word ' hermeneutic' suggests a process of understanding, of critically reading a text, or situation, with the aim of better insight, not providing a tidy system to be available as a correct answer, but as a witness to God's love, through which "the church is built up and energised for mission, the believer is challenged, transformed and nurtured in the faith, and the unbeliever is confronted with the shocking but joyful news that the crucified and risen Jesus is the Lord of the world." (Wright 2009:40). Perhaps we could take our cue from ancient Mediterranean culture: The future was experienced in the present; tomorrow is tackled when it arrived; the past thus served as a mirror held up to the present and problems were solved in the light of the past (Malina, Joubert & Van der Watt 1996:105).

Stated in other words, hermeneutics as an aspect of theological study is the process of theoretical justification (or explanation) - in a credible and critical manner - about the Christian religion (Van Huyssteen 1987:2). By following the contours of the biblical witness, Christians tell the story of God's actions in human history through their testimony. They testify about God's goodness, a goodness He has made known, revealed and which defines His purposes (Güder 2000:29). Moltmann-Wendel & Moltmann (1983:88) aptly summarized the New Testament testimony as "the great love story of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit" in which the whole creation and humankind are all together. This lead Migliori (2004:68) to state that God's love was presented originally through Him as Father, is humanly enacted in this world by the Son and becomes vital and present until today through the Spirit.

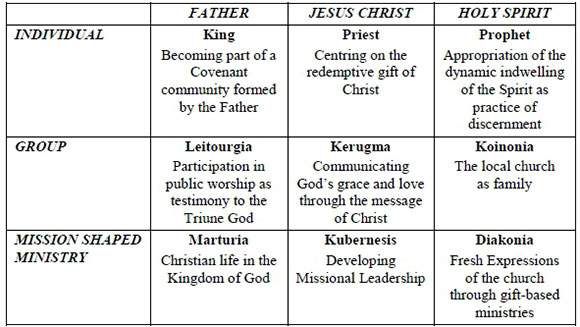

When missional ecclesiology is viewed through this filter we can build into the framework the notion that Christians share in the ministry by following Christ's example as Prophet, Priest and King (Leith 1993:159). God's children are called individually as well as collectively to participate in the life of the Trinity. Thus we can distinguish this vocation through a cross-grid matrix pertaining to the individual Christian's sharing of the prophetical, priestly and regal functions, the community of believers' participation in these functions, and the way the church's mission is aligned with that of God in the way his Kingdom is presented to this world.

- A relational hermeneutic seeks to understand missional ecclesiology through the filter of the local church

Hybels (2002:27) stated that the local church is the hope for the world. Viewing missional ecclesiology through the filter of the local church, we are reminded of the ancient history of faith communities in a tumultuous time, when the Christian religion was a marginalised, persecuted grouping of the Roman Empire (Mead 1991:9). The early church was aware of itself as a religious community surrounded by a hostile environment to which each witness was called to witness about God's love in Christ. They viewed themselves as bearers of the euanggelion, a term that in this time was frequently used as description for the good news about the Kingdom of God that was being personified in Jesus.

The local church functioned at the centre of this task. It was a community that lived by the power and values of Jesus (Mead 1991:10). These values and power were preserved and shared within the intimate community through apostolic teaching and preaching, the fellowship of believers and ritual acts such as the breaking of bread and wine in the Eucharist. Kreider (1999:23) showed how these early churches attempted to nurture communities whose values would be different from those of conventional society. It was assumed that people would live their way into a new kind of thinking. Thus, the socialisation, professions and life commitments of candidates for church membership would determine whether they could receive what the Christian community considered to be good news.

On congregational level this hermeneutic reading of missional ecclesiology enables better understanding in the way the local church builds up its members to participate in ministry: through acts of worship and prayer, through teaching and equipping and through the way the church is structuring itself relationally as God's family. In this regard, biblical passages to be re-read through the filter of a relational hermeneutic need to be revisited, such as the gospel of John - where Van der Watt (2000) successfully showed how the family metaphor is utilised, Acts, Ephesians and Revelation 4-5.

- A relational hermeneutic seeks to understand missional ecclesiology as participation in God's missional ministry to this world

According to Mittelberg (2000:49-61) a gap exists between contemporary church culture and secular society. The church has become so far removed from postchristian society that its own culture has become an obstacle in communicating God's message, needing to cross an additional bridge towards the secular worldview and human consciousness in order to be able to engage in God's mission. Therefore, the contextual filter for a missional hermeneutic is an intentional choice to understand the church from the viewpoint of God's work in the community, rather than the needs of the congregation.

This mission-shaped ministry approach -borrowing a phrase coined by the Church of England - is a way of describing the different ethos and style of ministries traditionally conducted by the local church, as they are designed to reach a different group of people than those already attending the original church. This approach correlates with the trend towards creativity identified by Niemandt and is innovative in its essence. It is "creating spaces for the invitation to follow Jesus to be heard in new ways..." (Drane 2010:160).

This hermeneutic is more fully developed when the church invests in the Kingdom of God, the intentional developing of missional leaders and the freedom of expression of church members to start ministries according to their particular gifts and passion.

Conclusion

How, then, should a relational hermeneutic look - one that takes the integration between theological paradigms and scientific disciplines seriously?

A relational hermeneutic takes as its first cue the common purpose with which theology is practiced. As a whole the aim is to take part in God's mission to the world and our engaging with the brokenness that He wishes to mend. This shared vision serves as the focal point of all theological reflection.

A second cue is taken from the essence of the church's ministry to the world. As living testament of God, we are a communicative organism, honour-bound to go and share what God is doing. Within the different narratives we all share the common bond of being one in Christ (Eph. 4:1-6). To this extent the church is essentially an interpersonal organism -focused on the restoration of people's relationship with God as well as with each other. The New Testament has approximately 96 different 'one another' texts filled with imagery depicting the relational character of Christ's body. In the context of my own theological tradition the Confession of Belhar testifies to the fact that the Bible demands the visible unity of God's people through reconciled relationships as one of the prerequisites for the world to believe in God.

The third cue for a relational hermeneutic grows from the realisation that every one of the three paradigms has the challenge to develop theories of ministry practice for our current context. Since we live in an oxymoronic culture, the developers of these practices would do well to start listening to one another. As there is no one correct way of doing ministry, no single possibility to interpret biblical texts, or a definitive manner with which pastoral care is accomplished, a relational hermeneutic will seek to draw from each paradigm the most authentic developments, in its quest to bridge the chasms. Faced with the reality of the South African context, a unified voice should be sought for the public discourse that demands from the church reasons for the hope it propagates (cf 1 Pet 3:15). Therefore the modernist churches of the well-to-do suburbs should humble themselves before the township voices that cry out the plight of the poor and destitute. The pre-modern fundamentalists should start to listen to the echoes of dignity that cannot be trapped in legalist language. And the late-modern dreamers should utilise their capacity to create meaning through concrete deeds of service in communities beyond their comfort zones.

Finally, a relational hermeneutic cannot be anything else than personal. Taking time to cross cultural, social and economic boundaries can only affect the scientific scope of theological reflection positively. The prophetic voice of public theology will sound with increasing clarity when God's people now, trust and love one another regardless of their race, gender or social standing.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barker, JA 1985. Discovering the Future, St Paul, ILI Press. [ Links ]

Bird, A 2011. Thomas Kuhn, In Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, viewed 2014-06-30 from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/thomas-kuhn/#pagetopright. [ Links ]

Bosch, DJ 1991. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission, New York, Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Burger, C 1999. Gemeentes in die kragveld van die Gees: Oor die unieke identiteit, taak en bediening van die kerk van Christus, Wellington, Lux Verbi/BUVTON. [ Links ]

Caputo, JD 1997. The prayers and tears of Jacques Derrida: Religion without religion, Bloomington, Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Drane, J 2010. 'Resisting McDonaldization: Will 'Fresh Expressions' of church inevitably go stale?', in C Mortenson & A0 Nielsen (eds.), Walk humbly with the Lord: Church and mission engaging plurality, pp. 150-166, Grand Rapids, William B Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Fowler, SE 1995. "The New Testament, Theology, and Ethics," In Hearing the New Testament: Strategies for Interpretation, pp. 394-410, Grand Rapids, William B Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Green, JB 1995. "The Practice of Hearing the New Testament", In Hearing the New Testament: Strategies for interpretation, pp. 411-427, Grand Rapids, William B Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Güder, DL 2000. The Continuing Conversion of the Church, Grand Rapids, William B Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Guillemette, L & Cossette, J 2006. Deconstruction and différance, viewed 2012-08-15 from http://www.signosemio.com. [ Links ]

Hairston, M 1982. "The Winds of Change: Thomas Kuhn and the Revolution in the Teaching of Writing", In College Composition and Communication, Volume 33, no 1. pp 76-88. [ Links ]

Hassan, R 2008. The information society: Digital media and society series, Polity Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Heitink, G 1993. Praktische Theologie, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Hirsch, A 2006. The Forgotten Ways: Reactivating the missional church, Grand Rapids, Brazos Press. [ Links ]

Hybels, B 2002. Courageous Leadership, Grand Rapids, Zondervan Publishing House. [ Links ]

Keifert, PR 2006. Ons is nou Hiér: 'n Nuwe era van gestuur-wees, Wellington, Bybelmedia. [ Links ]

Kreider, A 1999. The Change of Conversion and the Origin of Christendom, Harrisburg, Trinity Press International. [ Links ]

Kuhn, T 1996 (3rd ed.). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Leith, JH 1993. Basic Christian Doctrine, Louisville, Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Lyotard, JF 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Manchester, Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Malina, BJ & Joubert, SJ & van der Watt, JG 1996. A Time Travel to the world of Jesus: A modern reflection of ancient Judea, Halfway House, Orion Publishers. [ Links ]

McKnight, S 2008. The Blue Parakeet: Rethinking How You Read the Bible, Grand Rapids, Zondervan Publishing House. [ Links ]

McLaren, BD 2000. The Church on the Other Side: Doing ministry in the Postmodern Matrix, Grand Rapids, Zondervan. [ Links ]

Mead, LB 1991. The Once and Future Church: Reinventing the congregation for a new mission frontier, New York, The Alban Institute. [ Links ]

Migliori, D 2004 (2nd ed). Faith Seeking understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology, Grand Rapids, William B Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Miller, MR 2004. The Millennium Matrix: Reclaiming the past, reframing the future of the church, San Francisco, Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Mittelberg, M 2000. Building a Contagious Church: Revolutionizing the Way we View and Do Evangelism, Grand Rapids, Zondervan. [ Links ]

Moltmann-Wendel, E & Moltman, J 1983. Humanity in God, New York, Pilgrim Press. [ Links ]

Morrison, C.C., 1910, "The World Missionary Conference", In Christian Century, viewed 2014-07-007 from http://www.religion-online.org/showarticle.asp?title=471. [ Links ]

Niemandt, CJP 2012. 'Trends in missional ecclesiology' , HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), Art. #1198, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.1198. [ Links ]

Osmer, RR 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction, Grand Rapids, Wm B Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Pettersson, R 1989. Visuals for Information: Research and Practice, Englewood Cliffs, Educational Technology Publications. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P 1991. From Text to Action: Essays in Hermeneutics, Evanston, Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Saxby, S 1990. The Age of Information: The Past Development and Future Significance of Computing and Communications, New York, New York University Press. [ Links ]

Smit, G 1997. Ekklesiologie en Gemeentebou: 'n Prakties-teologiese studie (Ecclesiology and Congregational Development: A Practical Theological Study), DD-dissertation (unpublished), Pretoria, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Smit, G 2008. "Die ontwikkeling van 'n strategiese gemeentelike ekklesiologie: Oppad na 'n missionerende bedieningspraxis (Developing a strategic congregational ecclesiology, Towards a Missionary Ministry Practice)", Acta Theologica, Volume 28(1):161-175. [ Links ]

Sweet, L 1999. Soul Tsunami: Sink or Swim in new Millennium Culture, Grand Rapids, Zondervan Publishing House. [ Links ]

Van der Ven, JA 1993. Ecclesiologie in Context, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, JG 2000. Family of the King: Dynamics of metaphor in the Gospel according to John, Leiden, Brill. [ Links ]

Van Huyssteen, W 1987. Teologie as Kritiese Geloofsverantwoording, (Theology as Critical Religious Accountability), Pretoria, Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Wright, CJH 2006. The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible's Grand Narrative, Downers Grove, Intervarsity Press. [ Links ]

Wright, NT 2009. Justification: God's Plan & Paul's Vision, Downers Grove, Intervarsity Press. [ Links ]