Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445X

Print version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.114 Stellenbosch 2015

ARTICLES

Transforming congregational culture: Suburban leadership perspectives within a circuit of the DRC

Ian Nell

Practical Theology Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

On 27 April 2014 we celebrated twenty years of democracy in South Africa. Celebrating this important day in our history also afforded us the opportunity to reflect on what has transpired in our country during the past two decades. From theories in theology and social sciences we learned that what is happening in the broader context in society directly influences the way we congregate in faith communities. And the way we congregate and structure faith communities once again influence the way leadership is exercised. In this contribution different theoretical constructs are used as interpretive frameworks to view the transformations that occurred in a Circuit of sub-urban congregations of the Dutch Reformed Church during the past twenty years, specifically concentrating on the leadership processes. The results of the data are also interpreted through the lenses of Mary Douglas's 'enclavement theory' and do not only open up a window on the past but also provide some clues for looking at the factors involved in the processes of transformation that is so prevalent in these congregations. The article will conclude with some theological reflection on leadership practices related to these processes of transformation.

"The secret of change is to focus your energy, not on fighting the old but on building the new" - Socrates.

Key words: Transformation; Congregational Culture; Congregational Studies; Leadership; Enclavement Theory

Introduction

The year 2014 introduced the opportunity not only to look back over twenty years of democracy in South Africa, but also to reflect on the impact that the cultural and societal changes had on faith communities. In South Africa we experienced over the past two decades what scholars call a 'collapse into modernity' (Smit, 2008) and the impact of this collapse can be seen in many different ways and forms in the life of faith communities and their leaders. A scholar such as the late Steve de Gruchy (De Gruchy et al., 2008) even speaks about 'another country' to emphasise the impact of the changes that took place when he reflects on the challenges for leadership in this 'new context' after the end of the apartheid era.

Botman's reflection (2014:10) on what is happening within the context of universities in South Africa could apply just as well to what is happening in faith communities. He writes: "With rapidly shifting societal needs worldwide, most universities have gone into ' transformation mode' in order to deal with the pressures of serving people with less space and money and to remain relevant in the knowledge economy." It is, in a certain sense, the impact of this 'transformation mode'2 on faith communities and their leaders that I wish to explore in various ways in this article through theoretical perspectives and an empirical input from a specific group of leaders in a sub-urban setting.

In the light of the theme of the conference and especially with the focus on the ' urban' as the next social construct or sphere to be investigated in the course of the project, the basic research question that the article will address can be formulated as follows: What can we learn from a number of ministers in a suburban circuit of the DRC concerning their experience of the societal changes (transformation) over the past twenty years and the impact it has had on the way in which they exercise their leadership responsibilities? Before we turn to the descriptive-empirical part and the presentation of the data a number of theoretical points of departure will first be discussed. The theoretical perspectives informed the questions put to respondents in semi-structured interviews. After the theoretical discussion and the testing of some of the constructs in the empirical part, the data will be interpreted by making use of a number of theoretical inputs in an effort to draw some conclusions on what was discovered on the topic of the transformation of congregational culture among this specific group of leaders.

Theoretical Perspectives on Transformation3

The literature on transformation theories concerning communities of faith is vast and impressive and therefore it is necessary to make some choices upfront. My choice for the theoretical points of departure falls on the theories of Heitink (2001, 2004), Robinson (2003) and Osmer (2008). I chose Heitink because of the way in which he gives a ' historical perspective' on the development of the office of the minister over more than five hundred years, helping one to understand the way in which changes in society influence the way in which faith communities operate. The choice for Robinson comes from the fact that I am involved in a Master' s programme at the Faculty of Theology in Stellenbosch, South Africa, focusing on missional leadership where we use Robinson's theory concerning the transformation of congregational culture to help students interpret their own congregation's contexts. Osmer' s theory on the different tasks of leadership is very helpful in reaching a deeper understanding of the roles and expectations of leaders in congregations.

The Dutch practical theologian Gerben Heitink studied the development of ministry over the past five hundred years in the Netherlands and named his book: Biografie van de dominee (2001). He worked with the hypothesis that one can only understand the developments in the ministerial profession in the light of developments in the church and that such developments in the church can be understood only by understanding developments in society. He describes how the role of the minister changed during the various periods, from the initial years in Geneva, to the public role in the time of close church-state relations to the pedagogue of the 'volk', inner church administrator, pastoral leader, therapist to strategic leader. In an article he wrote in 2004 he again pays attention to the challenges that the shift from modernity to post-modernity posed to church life and the pastoral profession. Although the roles of the leader will differ from context to context his basic hypothesis of the 'direction of influence' forms a central point of departure in my own thinking about transforming congregational culture.

In the work of Robinson (2003) he concentrates on the changes in congregations and writes: "Observation and experience has led me to the conclusion that no single factor is more important to congregational vitality than leadership." In a chapter dealing specifically with leadership he draws on the work of Ron Heifetz in identifying six strategies for leadership in situations of what he calls 'adaptive challenge'. These six are (2003:125-135): (1) getting to the balcony (2) identify the adaptive challenge (3) regulating distress (4) maintain disciplined attention (5) give responsibility back, and (6) protect leadership from below. Space does not allow discussing each of these strategies, but in the empirical work of the next section it was especially the first two strategies that helped in formulating the first two questions that were put to the respondents.

As part of the so-called identification of the adaptive challenges that Robinson refers to in his six strategies, I find the distinction between different forms of leadership that Osmer (2008) refers to as a valuable way of trying to figure out on which of them the respondents spent most of their time and also try to probe into the underlying reasons for this. The three forms Osmer (2008:178) discusses are the following: Task competence: Performing the leadership tasks of a role in an organisation well. Transactional leadership: Influencing others through a process of trade-offs. Transforming leadership: Leading an organisation through a process of 'deep change' in its identity, mission, culture and operating procedures. Moreover, Osmer (2008:179) is of the opinion that these three forms of leadership are all necessary in faith communities, but that today, especially in the mainstream Protestant churches, the greatest need is for transformation leadership. In the second question put to the respondents they had to answer on which of these forms they spend most of their time and also offer some reasons for the choice.

Research Methodology

The research design for the empirical research that I used, works with an interpretive perspective in qualitative research with its roots in hermeneutics as the study of the theory and practice of interpretation (Henning et al, 2004:19-21). The aim of this kind of empirical research is to provide contextually valid descriptions and interpretations of human actions, which are based on an insider' s perspective of people and their world. The research was done by means of a semi-structured interview schedule (six questions) with a sample of leaders in a specific suburban circuit of faith communities where they exercise different leadership functions.

The theories discussed in the previous section formed the basic framework for the development of the semi-structured questionnaire. As part of the questions I asked the interviewees to describe and to tell stories in what Henning et al. (2004:53) calls "someone's narrative version of her lived experience (as in the phenomenological interview)". Semi-structured interviews, allowing openness for narrative and lived experience, still need interpretation to make sense of the data. Once again the basic research question I am addressing is: What can we learn from these ministers in their suburban context concerning their experience of the societal changes (transformation) over the past twenty years and the impact it had on the way in which they exercise their leadership responsibilities?

I chose the Durbanville Circuit of the Dutch Reformed Church as sample4 because the Circuit functions within the Northern suburbs of the Cape Town Metropole and in that sense represents one form of an ' urban lifestyle' . Another reason for choosing this specific Circuit relates to the fact that I served as minister in a congregation in this area for ten years. In some ways I therefore do have something of an 'insider's perspective' on the activities of the ministers in this area. The Circuit is made up of 10 congregations with more or less 28 000 members, making it the biggest Circuit of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa. At the moment 28 full-time ministers are serving the ten congregations with another five youth workers employed by some of the congregations. The population5of ministers is 28. After receiving ethical clearance from the University's Ethical Committee I sent a questionnaire via email to each of the ministers. The questionnaire explained the reason for the research and asked six questions.6 After a fortnight I received 16 responses with a 'thick description'7 of their experiences making it a very comprehensive data set. For the sake of anonymity I numbered the answers in the chronological order that I received the responses and for the analysis I will also use this number to refer to them. One of the results of doing this kind of analysis is what scholars call the eventual ' saturation' 8 of the data.

Empirical Results and Organizing of the Data

The richness of the data and the amount of information that I received makes it impossible to give proper attention in one article to the answers to all six questions. In this article I will therefore concentrate only on the first two questions and answers to determine what we can learn about the 'transformation mode' operative in the different faith communities that I referred to in the introduction. I do this in quest of finding some initial answers as response to the basic research question of the study.

■ Question 1: If you get out in a figurative sense onto the 'balcony,' looking back over the past twenty years, what were the contextual challenges that your ministry faced and that you also feel made an impact on your ministry?

After initially reading through the respondent' s answers to question one, I realized that the social action theory of Talcott Parsons9 (1977) could be helpful in terms of categorising10 the data into the four different factors he uses in his action theory. He makes use of the acronym AGIL to describe the different actions or elements at work in social systems. The letters of the acronym stand for: (A) adaptation (G) goal attainment (I) integration and (L) latent function or pattern maintenance. Each of these functions within specific spheres namely the economic sphere (money), the political sphere (power), the sphere of influence (socialisation and integration) and the sphere of commitment (values and culture). These four different factors will now be used as headings to organise the data and to try to see if there are indeed patterns developing from doing it in this way.

Economic Factors

The following codes capture some of the economic thinking of certain of the respondents as seen in extracts from the responses:

i. The 'Sandton of the Cape'

■ Many businesses have been established within the boundaries of the congregation. Durban Road, considered as the Golden Mile passing Tyger Valley shopping centre, has developed and expanded dramatically, so much so that the area is known as the Sandton of the Cape (respondent 12).

■ I have now been a minister in congregation X for 11 years - a suburban congregation with a unique demography in comparison to the rest of the country in the sense that it falls under one of three areas in SA with the highest income per household (respondent 13).

It is interesting that three of the congregations (out of a total of 10) do not fall in this ' middle and upper class' with regard income. From this cluster of congregations I received only two responses, but one can immediately sense that these congregations do not fit into this so-called 'Sandton of the Cape.' See the following response:

■ Congregation X is to a great degree a 'flow through' congregation. With that I mean that most of the people are first home owners and therefore only temporarily in the area. As soon as they make progress in their work environment or their income rises, they move on to better suburbs. This results in the following: financial income of the congregation is very low because the members are starters in the labour market and are still trying to make it financially (respondent 15).

■ From these responses one can sense a class differentiation between these congregations and those located in suburbs on 'the other side of the ridge' and closer to the ' Golden Mile of Tyger Valley' .

ii. The Economisation of Middle Class Lifestyle

■ Because of the ' economization' of the middle class lifestyle people are not involved in voluntary work (e.g. care, catechism classes, fundraising etc.). The overwhelming frame of reference is one of delivering services in exchange for payment and members carry this understanding into their church involvement. Voluntary service is thus evaporating because of this attitude as well as the busy daily schedules. At the same time members are eager to give money, but not necessarily for the institution (the church) but for specific activities (respondent 3).

■ Many Afrikaans speaking people seek their salvation in the strengthening of their economic position to compensate for the loss of political power. This economic empowerment results in our members looking for the best schools for their kids, good medical care, etc. In my previous congregation I became aware of the challenge of the consumer culture to our members (respondent 6).

The economisation of the middle class lifestyle as a way of creating a new sense of power is very obvious from these responses.

iii. The Influence of a Consumer Culture

■ Members are attending activities, talks and worship services of different churches across denominational borders, especially when there is a well-known speaker. On the one hand it is a good thing that members are not intimidated by congregational boundaries and go to places where they find spiritual nurturing. On the other side it is an unhealthy habit if members run after the next big happening, the next well-known speaker, the next exciting church service. It can become very individualistic, focused on satisfying the spiritual and emotional needs of the individual. This conduct does not contribute towards building the faith community and enhancing the Kingdom (respondent 5).

■ Many members left the DRC for other churches (in some cases for no other church). In the consumer culture the DRC was not a good 'brand name' and members that stayed in the church started to take up a position of defence and maintenance that inhibited creative reflection on the role of the church in the community (respondent 6).

From the data one can see how the consumer culture permeated the communities where the members of these congregations stay.

iv. Poverty and Dwindling Membership

■ Some of the largest challenges revolve around poverty. A related problem is mobilizing the community for service and an altered perception not to be inward looking, but attending to what is going on in the outside world (respondent 8).

■ A further challenge is the impoverishment of retired people, especially in our community. Old people are living longer and their savings are not enough. We have a large component of older members who of course wish to be served in a specific way - for example through personal attention via home visitations. This challenge has a large effect on the church finances (respondent 9).

■ The economic reality of the RSA (and the world) had a profound influence on the congregation's financial situation. The 'affordability' of full-time ministers became an issue. Our congregation became smaller (respondent 10).

■ Finances are very tough, members have lessened, the number of children declined. With three ministers there may be too much working capacity for too few people (respondent 11).

It is interesting to see the paradoxes in the responses concerning poverty. On the one hand some refer to poverty in general; in other cases the worldwide economic recession of 2008 had a definite impact on the financial situation of congregations.

If one uses Parsons' concept of 'adaptation' when he discusses the economic factors in his theory, it is interesting to see in what ways the members (according to the ministers) adapted to a new style of living directly linked to their economic position and even more importantly, the influence it has on their participation in voluntary work in the faith communities. This may be one of the accompanying factors that has to be borne in mind with regard to processes of suburbanisation.

Political Factors

One could sense from a number of responses that political factors were one of the key causes responsible for and driving changes in society. Here are some examples from the data:

i. The Impact of the 1994 Elections - Dawn of Democracy

■ The most important contextual challenges, with regards to the changes during the past twenty years, were brought about by the first democratic elections in 1994. The Groups Area Act of 1950 was repealed on 30 June 1991 and caused the immediate context of traditional churches DRC to change dramatically. People of all races were allowed access to cities and neighbourhoods. The church was now compelled to face these realities and to confront them or to crawl back into its shell (respondent 1).

■ The initial great excitement of a new political order was replaced by pessimism about politics (respondent 10).

ii. A Change in the Playing Field

■ The political playing field in which churches operated very quickly changed since the 90s. On the missional and inclusivity levels the democratic and equality politics implemented since 1994 helped congregations to understand the Bible and life in a different way and to embrace integration on many levels (respondent 2).

iii. Fear and Experience of Loss

■ The main challenge twenty years ago was the transition in South Africa - the fears that many people had about the transition to democracy. I think the biggest challenge at that time was to help people to cope with many losses (loss of community, loss of power or control over the local government and traditional certainties), to start new processes without being overwhelmed by them; and to start to think broader about the church (talks about the Belhar Confession has especially played a role, although most people were dismissive towards the Confession) (respondent 6).

■ The aftermath of the previous political dispensation and the uncertainty about what the future holds, probably made us more sensitive for our own survival (respondent 7).

It is quite easy to see how the political changes that came about because of the democratisation of South African society since 1994 had an enormous impact on all levels of society. It is especially the fear and experience of loss which this uncertain situation created for the members of the DRC faith communities that created ambiguous feelings about the future.

Factors Relating to Processes of Integration and Socialisation

The factors pertaining to processes of integration and socialisation are not always easy to distinguish from those related to culture and identity. The basic distinction that I try to use is between what Parsons calls the 'sphere of influence' in the case of integration and socialisation and the ' sphere of commitment' in the case of culture and identity. See the following as examples from the data.

i. The ' Bubble Existence' of the Wealthy Middle Class

■ The biggest challenge for me is to reflect with believers on the calling of our country within the privileged suburban 'cocoon' of Durbanville (respondent 6).

■ I am in a congregation with a unique demographic in comparison with the rest of the country in the sense that the congregation is situated in one of three areas with the highest income per capita in South Africa. The biggest contextual challenge in this regard is that most of the people do not realise the 'bubble' that we are living in and react unrealistically, superficially and without deeper reflection on the challenges facing our country (respondent 12).

■ The largest contextual challenge here is that most people do not always realise what ' bubble' we are living in, and sometimes react unrealistically, superficially and thoughtlessly regarding the challenges of our country. Also, rich people struggle with the same problems as others - they just hide it in a better way! It causes people to easily cut themselves off from their environment and project a particular false impression to the outside world; neighbours do not know each other by name, and people are unaware of the need (at all levels) here within our own borders (respondent 13).

ii. The ' Birds-of-Feather' Culture

■ The ' birds-of-feather' culture involves that I go where there are people similar to myself. People of our race, our social class, our language, our thoughts, our preferences, our spirituality. This is understandable. And different churches have different approaches to this phenomenon. But how do we break through the boundaries? Especially around race and social class? (respondent 5).

iii. A Change in Demography

■ Rapidly growing number of members due to huge demographic changes. Many new members - not because of evangelism, but rather because of demographic and socioeconomic shifts. The ministry is therefore facing constant new and unique challenges (respondent 3).

■ Where every second house belonged to a DRC member 25 years ago, it is now much more English-speaking people, Chinese people and people of colour that moved into our area (respondent 12).

■ Demographic changes also reveal the fact that where white people moved away they were replaced by coloured people. These people are usually not Afrikaans speaking or even from the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) (respondent 15).

The last response was once again from one of the Kraaifontein Congregations showing a different kind of demographic shift at work.

iv. The Phenomenon of ' Macro-Congregations'

■ With my arrival in congregation X during 2007, I was exposed for the first time to the culture of a macro-congregation. In a sense it made the issue of members who were leaving the DRC a bit easier because it is not felt immediately; the moving away of members kind of disappears in the larger system (respondent 6).

■ In our macro-congregation people can easily fall through the cracks, and feel isolated (partly because of their own doing). Small groups operate on the basis of free association (which in itself is not necessarily a bad thing); the problem is that people who were in the past cared for through the ward system now feel completely neglected. I am certainly not a proponent of the ward system and do not want to see it returning (wards also created the illusion that people were cared for); I just think that our congregation should enhance the experience of intimate communion and caring (respondent 13).

v. The Development of new Religious Markets

■ Over the past few years the move to the charismatic churches became stronger, while a larger number of members openly aired their doubts, especially with regard to books such as those of Richard Dawkins (respondent 6).

■ Several other religious groups established themselves within the town's boundaries, for example: Skaapland Conference Centre, Barnyard Theatre, Local Primary School hall and nearby Voortrekker Hall. Believers in our region thus have a wide choice of different styles of ministry. The challenge is to develop you own unique style of ministry in the midst of all these different styles (respondent 12).

vi. The Digitalisation of Communication

■ The rate at which electronic communication, social media, web communications and visual media struck the ministry is astronomical. Younger generations and their value preferences flourish in contexts of e-communication. If diversity is to be embraced the hard copy preferences should also be accommodated. I suspect the time of bookshelves full of commentaries and theological heavyweights is being replaced by computers, search engines and huge hard drives in ministers' offices.

Some imaginative images emerged in the data such as 'the bubble existence' and 'birds-of-a-feather culture'. Together with the changes in demography, the phenomenon of macro-congregations, the development of new religious markets and the digitalisation of communication one can glimpse the complex processes influencing socialisation and integration taking place in these faith communities.

Factors Relating to Culture and Identity

The factors regarding identity and culture normally function at the deepest level of communities relating to people's genuine commitments and patterns of action. See the following codes that developed from the data.

i. A Change in the Psyche and Loss of Credibility in the DRC

■ The same political changes also had a huge impact on the minds of members in the DRC. The DRC lost her status as a national church - "the National Party at prayer." With this, the questioning of the DRC' s integrity in the eyes of the larger society, but also amongst its own members, increasingly became verbal and public (respondent 1).

■ The second issue is that the DRC increasingly lost its implicit position in people's lives. Many people have left the DRC to other churches (or, in some cases, to no church) (respondent 6).

■ Durbanville is traditionally a rich, white community. I would say that the first challenge was and is to shake of the ' baggage' of the previous era and with it the ' old' DRC. In other words - how do we change our members' minds about their calling to make a difference in our context? But the other side of the coin is also true - how do we get the surrounding people to trust our congregation again? Especially because our context did not change much during the past 20 years - we are still quite rich and the church is still pretty white, because that's what you see around you in our town (respondent 8).

■ The credibility of the DRC, due to factors such as apartheid, causes a lot of damage - specifically among the younger generations (respondent 10).

One can sense the impact that the changes had on the psyche and specifically the loss of credibility that many DRC members experienced. It looks as though the baggage of the past will still have to be borne and taken into consideration for another generation or two.

ii. A Loss of Tradition and Ritual

■ The culture to go away on holidays and long weekends, breaking the rhythm of the church year, means that the most important weekend of the year, Easter, is not well attended. On the one hand it is a good thing: families make an effort to spend quality time together. On the other hand it is not contributing to the family of faith (respondent 5).

iii. A Change in the Model of Ministry

■ To change the culture of specific expectations in people's minds, for example -many members live with a certain expectation of the church and minister to continue to operate in the same way as 20 years ago, although living in modern times. They live with internet, using state-of-the-art technology in their careers, but they would like the church' s ancient traditions to be preserved. It was always in my ministry one of the biggest challenges to change the culture of church and congregational life in people's minds. It takes time, but if you succeed, it becomes easier. I suspect the deepest motivation for members to be served by a model that is 20 years old, is their deep need for personal attention in an age of speed (respondent 4).

iv. Processes of Strategic Planning

■ We went through intense strategic planning processes, formulated a mission and vision, articulated as: "We are disciples of Jesus together in the service of God's kingdom" (respondent 7).

■ The church repeatedly had to adapt its course by making use of strategic processes to continue to stay relevant amid a postmodern environment (respondent 8).

v. Meritocracy

■ We find ourselves in a society driven by competition, living under the impression that we can buy everything we need or work hard enough to earn it (respondent 13)

vi. Globalization

■ A last big contextual challenge is the impact of globalisation on the psyche of South Africans. The isolated and protected life during the days the National Party was in power and the DRC a 'volkskerk' ended and in many ways people reacted morally, intellectually and financially to these bigger trends in a globalising world by going with the flow (respondent 1).

vii. Secularisation and Loss of Spirituality amongst Clergy

■ A growing tendency of secularisation that is in actual fact a following of international Western tendencies and economic and social challenges of our country (respondent 14).

■ Another reason is that only a few ministers do have an 'own' spiritual life. I am in the fortunate position to work with more than 120 ministers across the entire country. One can apply the findings of the Alban Institute concerning the spiritual life of the minister also in our situation (respondent 10).

From the data one can once again see a multitude of factors contributing to some significant changes in culture and identity among the members of these faith communities. One can sense a certain loss of identity and a feeling of shame because of the 'apartheid history' leading to a questioning of the integrity of the DRC and its members.

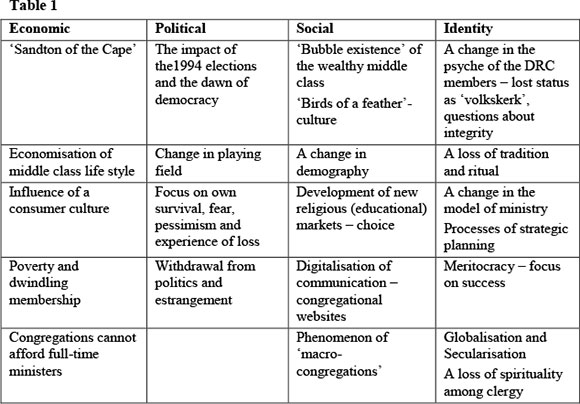

In table 1 I try to summarize the findings of question 1 under the different headings of Parsons' theory. Looking at the table one can see a tapestry of challenges developing in this process of transformation with each one of the factors influencing the other in a systemic manner.

■ Question 2: In the literature the distinction is made between task leadership (pastoral care, preaching, teaching etc.) transactional leadership (management, administration, etc.) and transformational leadership (the changing of the culture of the congregation). Which of these do you think took most of your attention during the past years and what would you say are the reasons for that?

The following examples from the data show the spread of responses among the three options:

Task leadership

■ Over the years 'task leadership' took up the most and constant attention - this is the best description of any minister' s everyday activities! Because of the demands the changing culture placed on our congregation - over the years we often had to adapt the culture of our ministry. This transformative leadership is not something we have ever completed or will complete, it moves in tandem with task leadership - perhaps deeper and slower (respondent 3).

■ Transformation leadership undoubtedly played the most important role. It was not what took up most of my time. Members' needs function on the level of task and transactional leadership. I spent a lot of time on the first two. If you wanted a successful ministry you could not neglect the first two, but transformation leadership was indispensable if you wanted to grow and make cultural changes (respondent 4).

■ I would say the most task, transactional second and third transformation. Transformation was often on the minds of our leadership team and we tried to focus on that. But the problem is that you are not sure how to bring about transformation. In other words, it' s okay to think about transformation and to speak about it, but what are the tasks and activities you need to do to achieve this transformation? And then, if you managed those tasks and things, how do you really measure whether the culture adapted sufficiently? (respondent 5).

■ I think the first two, no doubt, and for several reasons. The first is that it requires so much attention that we often have little time and energy left for transformational leadership. The second is that we are struggling to get clarity on the direction and nature of the kind of change required, and we often work with a kind of ' tweaking' model of transformation (hoping that small changes will eventually lead to a transformation) rather than purposeful work on culture changes (respondent 6).

■ It is quite a difficult question. If I have to be honest, task of leadership took up most of my time - specifically pastoral care and preaching. But I also spent a lot of time on transformational leadership -my colleagues (most of them!) and I took great pains to welcome diversity in our congregation (in terms of example spirituality preferences and dislikes) and we concentrated on the principle that the church' s culture must not be determined by tradition, but by inclusion (respondent 13).

Transactional Leadership

■ Transactional leadership undoubtedly took up most of my attention, while transformational leader increasing took up more time. Initially most ministers got involved with transactional leadership. The reason behind this is the rapid way in which the society changed around us. The culture shifted more quickly and more dramatically than we had expected. Twenty years ago the construct ' culture' was not used to refer to the changes or to help to understand them (respondent 1).

■ In the last year I was tasked with transactional leadership because I took over the role of 'head pastor' (more a kind of operational leader) with the responsibilities of management and administration (respondent 9).

Transformational Leadership

■ Transformational leadership. The reason is my own personal journey and most definitely my time in 'the desert' during 2000-2003 where I 'lost' my faith and God started with me anew (respondent 10).

■ Currently there is an emphasis on the change of the culture of the congregation. The average age of our members is less than 40, but on Sunday we don't see it. To create more openness between the different generations requires patience. We are moving too slowly to adapt to the demands of the community (respondent 11).

■ Without doubt I shifted during the last 10 years from task leadership to transformational leadership. I spend a lot of time trying to empower people for projects and ministries in the community, but the lack of good leadership caused me to fall back on transactional leadership of these ministries (respondent 15).

From the data it is quite obvious that the emphasis falls on 'task leadership' with a deep conviction that 'transformational leadership' is very necessary. From the responses it is however clear that most of the leaders are not quite sure how to go about performing transformational leadership and what it entails. One can sense that most of them are caught in the daily responsibilities of 'task leadership' and seldom have time to reflect on the challenges and responsibilities concerning transformational leadership. In one of the instances where the respondent referred to his preference for transformational leadership, he applied it to the transformation in his personal life and not with regard to the congregation' s context.

Interpretation of the Data through the Lenses of Enclavement Theory

Introduction

A basic question11 that could be asked at this stage, linking again with the theory of Heitink (2003), is: How do the social transformations affect the transformations in congregations specifically within the Circuit of the DRC and their leadership? By making use of Mary Douglas's concept of 'the enclave' I wish to propose that the result of these transformations was the development of a ' new enclave' in the Dutch Reformed Church in this suburban area. In the rest of this article I want to investigate, in the light of the data in the previous section, the characteristics of this new enclave within the circuit of the DRC and the ministers that I interviewed.

Of interest for this article would be the question whether the stereotypical theological structure12 that characterised the DRC during apartheid has in some way survived and perhaps re-emerged in different forms. For the sake of comparison13 I would like to discuss certain trends emerging from the data using the following keywords, namely stabilizing (or de-stabilizing), emigration (that is, inner emigration) and separation. The common denominator in all of these keywords, however, is the search for a (new) identity that permeates the young South African democracy and which, in my opinion, also has an impact on contemporary DRC congregations. In order to interpret this triangle, I first take a brief look at the so-called enclave theory.

The Enclave

The anthropologist Mary Douglas distinguishes between three social contexts, namely the Market, the Hierarchy and the Enclave.14 According to her, an enclave is usually formed by a dissenting minority developing a social unit maintaining strong boundaries.15 The religious nature and claims of the enclave are of specific importance for this article. Douglas describes the interaction between cultural and religious claims in the enclave as follows: "An enclave community can be recognized and described. It is not mysterious or unique. It starts in characteristic situations and faces characteristic problems. These invite specific solutions, the institutions in which the solutions are tried call forth a specific type of spirituality."16

An enclave - similar to which for instance formed around ' Afrikaner Identity' before and during apartheid - differentiates itself from other groups in order to create internal cohesion.17 An enclave is directed against the 'other', which could, again in the instance of historical Afrikaner identity, be seen as 'other' empires (such as the British - during the Anglo-Boer wars), 'other' races (as expressed during apartheid), 'other' languages (as exemplified during the so-called 'language movement': or 'Taalbeweging'), etc. Enclaves often operate with syndromes of anxiety (the 'black danger', or the 'red, i.e. Roman Catholic danger', etc.) and (often extreme) efforts to maintain the 'purity' of the enclave.

So, the haunting question remains: is a new 'enclave' in the process of being formed in the DRC? Julie Aaboe (2007) is quite convinced of this:

In the opinion of many the DRC stands today rather as safe haven, a frame within which different Afrikaner identities are developing and or re-constructing as clearly identified in the strong pietistic influence within the DRC today, mirrored in the influence of Charismatic and Pentecostal faith traditions, foreign to reformed theology. This represents a problem. If one looks at the different strategies of reconstructing Afrikaner identity in contemporary SA, this development follows not only in the footprints of its own history, but follows also a general global development where ethnic and religious communities, enclave themselves in a modern day laager.18

In what follows, I try to trace some characteristics of this new enclave by making use of the three concepts of stabilisation, emigration and separation.

Stabilisation

After the demise of apartheid, it was clear that many of the members of the DRC were desperately looking for (a new) security as an expression of their search for identity. They have been fundamentally disillusioned by the church. In the data we saw some of this disillusionment in code i under heading 4.1.4. Many people no longer trust the church, or at least have lost their blind and naïve loyalty to the church. The anchors that kept them tied to their moorings have been severed. Stability has become instability; a defined identity has been replaced with the search for a new identity.

The first and foremost problem facing the church is simply that many of these people are no longer present; the audiences who attend church services are rapidly decreasing (see code iv under 4.1.1). The past decade has seen a dramatic decline in the membership of the so-called mainline churches in South Africa (specifically also the DRC), mostly in favour of the charismatic movements and new developing religious markets (see code v under heading 4.1.3).

From these trends it is clear that many of the institutional (mainline) churches are now fighting for survival. Not only are the institutions19 of these churches viewed with scepticism, but also the theology is no longer accepted as obvious. The argument is understandable and goes like this: if the church misled us once in such a fundamental way, how are we to know that it will not do the same again? Others simply no longer engage in dialogue with the church.

This syndrome of apathy could also be ascribed to the accelerated dawn of modernity in South Africa (or collapse into modernity) since 1994. Whereas the country was isolated up to this point in time, its borders are now open to all the influences of globalisation. Processes of secularisation and privatisation (see once again codes vi and vii under 4.1.4) have been condensed into twenty years of democracy, with the expectation that South Africans should digest this in a much shorter time span than was the case in many other countries.

In many cases congregations are structured according to market-driven and consumerist considerations, coupled with the copious use of modern technology (see codes ii and iii under heading 4.1.3). Ministry has become geared towards the attraction and entertainment of people. One often has the feeling that now, since the controlling power of the church no longer exists, leaders and members of the church are frantically searching for new forms of security and identity.

Emigration

Whilst many (mostly white) South Africans have emigrated to other countries, those remaining in South Africa seem to be emigrating inwardly.20 They seek the safety of the enclave, rather than facing the 'other'. The hermeneutical movement of the apartheid era into the potential of the people' s pietistic reserves now takes on different forms: no longer to rectify the state of society according to certain nationalistic ideals, but simply to escape from all responsibilities regarding the new South African society.

This inward emigration of DRC ministry takes on many forms. In some cases the inward movement also represents a movement over, and thus avoidance of the harsh realities of the South African context (see code iii under 4.1.3).

Separation

It is clear that as a young democracy, South Africa is struggling to find its identity. In the euphoria of the political transition in 1994, much was made of the uniqueness of South Africa as a 'unity in diversity', epitomized in Archbishop Desmond Tutu's colourful phrase: rainbow nation. The dark days of ethnocracy seemed to be over. Since then, however, there have been some indications that people are again retreating into ethnic categories when trying to define their identity, sometimes even in fundamentalist ways (see code i under 4.1.4).

That the churches have been affected by this seems to be evident. A sad expression of this is the fact that the church (at least the Reformed Family of Churches) is still to a large extent separated structurally. The process of unification between the Dutch Reformed Church and the Uniting Reformed Church of Southern Africa (URCSA) seems to be derailing - with a large contingency of (white) members and ministers of the DRC indicating in a recent survey that they will not accept the Belhar Confession - which forms the heart of URCSA theology and church life. Therefore the unified, prophetic voice of (Reformed) churches in South Africa is absent: it is as if the church has lost its energy to protest against societal evils such as poverty, corruption, crime, stigmatization, etc.

It is as if the myth of separation between 'us' and 'them' - so integral to the ideology of apartheid - has come back to haunt us. The legalized borders of the enclave may have been abolished, but that does not necessarily mean that the spirit of the enclave is not still alive and well in South Africa, at least within DRC realities.

The Impact on Leadership

In the light of the previous section I wish to conclude by making some observations on the impact the social transformations has had on the leadership, by referring once again to the distinctions of the three forms of leadership that Osmer (2008) developed. Looking at the data that emerged from question two through the lenses of enclavement theory, one can sense why most of the ministers spend most of their time on task-leadership activities. The search for a new identity among the members and the leaders in these faith communities, because of the experiences of disillusionment in the past, calls for a pastoral presence in ' stabilizing the boat' amidst the storms of change. There is not much energy left to work towards the transformation of these faith communities at deeper levels. The legacy of forced removals during the sixties and seventies caused these suburbs to be dominated by white people with little exposure to the living conditions of people in poorer areas. There is little exposure at the level of integration and socialization in terms of Parsons' theory.

Conclusion

It is difficult, if not impossible, to predict how the future scenario in South Africa will turn out with regard to the development of new enclaves. What is clear, however, is that the leaders and their congregations will have to cross borders in order to be enriched and guided by the other. "We even need to move beyond denominationalism, if we hope to have any impact on society. We will have to revisit the hermeneutical space of the ecumenical church in order to address societal ills in our country. For it is exactly within this hermeneutical space that we may discover not a self-destructive ' stability,' but rather our true identity; not a misleading introversion, but rather vocation (to help transform society); not stigmatisation of, and separation from, the other, but rather the experience of facing the other and, in doing so, facing ourselves - and in the end, hopefully, the Other" (Cilliers & Nell 2011:7)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aaboe, J 2007. The Other and the Construction of Cultural and Christian identity: The Case of the Dutch Reformed Church in Transition. Unpublished PhD Dissertation: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Adams, RE 1992. "Is happiness a home in the suburbs? The influence of urban versus suburban neighbourhoods on psychological health." Journal of Community Psychology. 20:353-372. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J, Nell, IA 2011. 'Within the enclave' - Profiling South African social and religious developments since 1994. Verbum et Ecclesia, 32(1), Art. #552, 7 pages. [ Links ]

Denzin, NK, Lincoln, YS 2011. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Douglas, M 2001. In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilements in the Book of Numbers. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Durand, J 2002. Ontluisterde wêreld: Die Afrikaner en sy kerk in 'n veranderende Suid-Afrika. Wellington: Lux Verbi BM. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, S, Koopman, N, Strijbos, S 2008. From Our Side: Emerging Perspectives on Development and Ethics. Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers. [ Links ]

Heitink, G 2001. Biografie van de dominee. Baarn: Ten Have. [ Links ]

Heitink, G 2004. "Veranderingen in samenleving en kerk en de gevolgen voor het beroep van pastor." Verbum et Ecclesia. 25:502-518. [ Links ]

Henning, E, Van Rensburg, W, Smit, B 2004. Finding your Way in Qualitative Research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Osmer, RR 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Parsons, T 1977. Social Systems and the Evolution of Action Theory. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Robinson, AB 2003. Transforming Congregational Culture. Grand Rapids: Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing. [ Links ]

Smit, DJ 2008. "Mainline Protestantism in South Africa - and modernity? Tentative reflections for discussion." Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 49:92-105. [ Links ]

1 The article was originally a paper delivered at the second conference of the international research project with the working title: "Transforming religious identities and communities at the intersections of the rural, the urban and the virtual" that took place from July 2-4 2014 at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

2 'Transformation' is of course a charged concept. Du Toit (2010:ii) writes: "Transformation remains fundamental to the building of a just and equitable post-apartheid state. Few words in South Africa's political lexicon are vested with so much currency and moral weight. Without risking exaggeration, it is safe to say that the concept has become the central reference point that provides the momentum for the rebuilding of the South African state from its apartheid ruins."

3 An interesting theory that may also help to shed some light on what is happening in these types of communities is called 'suburbanization theory' in which psychological aspects play an important role. In a very interesting study where Adams (1992:353) questions whether happiness is a home in the suburbs, he looks at the influence of urban versus suburban neighbourhoods on psychological health. Although his data goes back to the seventies he arrives at the following conclusion: "Classic urban theory suggests that living in highly urbanized areas of the city results in social isolation, social disorganization and psychological problems." Living in the suburbs, however, is thought to be much more conducive to happiness, because suburban areas have a lower population density, lower crime and a more stable population when compared to urban areas. Using data collected in 1974 from the Detroit Metropolitan Area, this study evaluates this 'happy suburbanite' hypothesis. Results show that people living in the suburbs are no more likely to express greater satisfaction with their neighbourhood, greater satisfaction with the quality of their lives, or stronger feelings of self-efficacy than people living in the city. The analyses reveal that social integration and perceptions of the neighbourhood are associated with neighbourhood satisfaction, whereas employment status, age, housing satisfaction, and neighbourhood satisfaction are associated with good psychological health. The results also show that length of residence has the strongest effect on neighbourhood social ties and participation in local activities (my italics).

4 "Sampling is the process of choosing actual data sources from a larger set of possibilities. This overall process actually consists of two related elements: (1) defining the full set of possible data sources - which is generally termed the population, and (2) selecting a specific sample of data sources from that population. Note that this definition is stated in general terms that apply to both qualitative and quantitative research, because it is nearly always necessary to work with a sample of data sources rather than attempting to collect data from the entire population" (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011:799).

5 "A group of persons (or institutions, events, or other subjects of study) that one wants to describe or about which one wants to generalize. In order to generalize about a population, one often studies a *sample that is meant to be representative of the population. Also called *target population and 'universe'" (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011:240).

6 The six questions were the following: 1. If, in a figurative sense, you get out onto the 'balcony' and looking back over the past twenty years, what were the contextual challenges that your ministry faced and made an impact on your ministry? 2. Scholars distinguish between task leadership (pastoral care, preaching, teaching etc.). transactional leadership (management and administration) and transformational leadership (changing the culture of a congregation). Which of these three took up the most of your time over the past years and what are the reasons? 3. Do you think there was a shift during the past twenty years in the way people perceive the 'offices' (deacon, elder and minister). If so, why do you think did it shift and what would be the reasons for that? 4. Leadership frequently focuses on 'technical changes' (with the focus on tasks, roles and structures) and 'adaptive changes' (with the focus on the system and culture of a congregation). What were the technical and adaptive changes that your congregation experienced during the past twenty years? 5. The DRC accepted at the last General Synod a document on 'the missional nature and calling of the church'. How do you understand this missional nature within your ministerial context and how do you think does it influence your ministerial praxis? 6. What do you see from the 'balcony' as the challenges for your ministry during the next twenty years?

7 "Most efforts to define it emphasize that thick description is not simply a matter of amassing relevant detail. Rather, to thickly describe social action is actually to begin to interpret it by recording the circumstances, meanings, intentions, strategies, motivations and so on that characterize a particular episode. It is this interpretive characteristic of description rather than detail per se that makes it thick" (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011:297).

8 "Saturation is the point in data collection when no new or relevant information emerges with respect to the newly constructed theory. Hence, a researcher looks at this as the point at which no more data need to be collected... Some researchers consider a sample size of 15 to 20 as appropriate for saturation of themes during analysis; however, the sample size will vary depending on the context and content under study. Researchers also note that saturation cannot be achieved through frequency counts but instead must be achieved through an examination of the variations within the data and how these variations might be explained in the context of the emerging theory. Therefore, it is essential at the early stages of analysis to consider each piece of data equally because this allows researchers to locate, understand, and explain variations within the sample" (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011:192).

9 Parsons produced a general theoretical system for the analysis of society, which he called 'theory of action' based on the methodological and epistemological principle of 'analytical realism' and on the ontological assumption of 'voluntaristic action' (Parsons, 1977:27).

10 "Categorization is a major component of qualitative data analysis by which investigators attempt to group patterns observed in the data into meaningful units or categories. Through this process, categories are often created by chunking together groups of previously coded data. This integration or aggregation is based on the similarities of meaning between the individually coded bits as observed by the researcher. Categories in turn may be abstracted or conceptualized further to discern semantic, logical, or theoretical links and connections between and across the categories. The results of this process may lead to the creation of themes, constructs, or domains from the categories" (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011:73).

11 In an article co-authored by myself and Cilliers (Cilliers and Nell, 2011) we also asked this question but in a broader sense, looking at the influence of societal changes on the DRC in general.

12 Cilliers & Nell (2011) described this 'stereotypical theological structure' as: "One of the basic theological frameworks within which the DRC sought to guard over its identity during the apartheid era (and) could be described in terms of a triangular movement, namely the search for security (with the help of an 'eternal' myth), the appeal on national 'potential' to overcome adversity, and the projection of guilt onto the enemy as the ' other'".

13 This of course implies delimitation: many other trends could be identified, according to the perspective from which one views the contemporary South African scene.

14 Mary Douglas (2001) In the Wilderness - The doctrine of Defilement in the book of Numbers. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001:48f.

15 Douglas, In the Wilderness, 45-49.

16 Douglas, In the Wilderness, 49.

17 Julie Aaboe, The Other and the Construction of Cultural and Christian Identity: The case of the Dutch Reformed Church in Transition. Unpublished PhD, University of Cape Town, 2007:65.

18 Julie Aaboe, What does it mean to be a Christian? Paper delivered at Stellenbosch Conference, 31/08/2008.

19 It is interesting to note how many DRC congregations no longer use the name Dutch Reformed on their billboards and in their marketing. For some, the link to their historical roots has become an embarrassment.

20 Cf. Jaap Durand, (2002) Ontluisterde Wêreld. Die Afrikaner en sy kerk in h veranderende Suid-Afrika. Wellington: Lux Verbi.BM, 2002:60.